Mind-Boggling Medical History: creating a medical history game for nurses

Abstract

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191104/001This article examines the development of the resource Mind-Boggling Medical History, a card game developed to introduce medical and healthcare history to new and non-traditional audiences for the subject. We explore the methods we used to develop and improve the game, which was reliant on stakeholder participation. We then focus on the impact of Mind-Boggling Medical History on nurses, who have constituted one of the game’s key audiences, and explore its role in supporting nurses’ critical engagement with changing knowledge and concepts of evidence. We also evaluate the limitations in our own approach to collaboration with nurses. Through this, we elucidate the relative lack of engagement, historically speaking, there has been between humanities scholars and nurses. We conclude by pointing to ways in which resources like Mind-Boggling Medical History can open up the academic medical humanities to audiences that the discipline rarely caters to.

Keywords

gamification, medical history, medical humanities, Nursing education, nursing history, public engagement

Wandering wombs and tobacco enemas: gamifying medical history for nurses

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191104/002Mind-Boggling Medical History is an educational card game. Its development was funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) and it was created collaboratively by the University of Oxford and the Royal College of Nursing (RCN) Library and Archive Service. This article examines the development of the game and the opportunities and challenges of working with an audience of nurses. In the first section we will address the development of the game, how methods from museum studies were utilised to improve and enhance it, and who our target audiences were. We then focus on how and why we increasingly aimed the resource towards a key audience of nursing practitioners and students and the potential impact of doing so upon nursing education, as well as the medical humanities. Finally, we conclude by evaluating the outcomes and efficacy of the game, considering how Mind-Boggling Medical History has added value to nursing education, and showing how academic humanities researchers might contribute to healthcare education using intellectual tools borrowed from the museum sector.

The origins of Mind-Boggling Medical History lie in a late-night public event called ‘Wrong!’, which was organised in July 2013 by the Wellcome Collection and curated by the theatre director Sarah Punshon. The event focused on ideas of error and irrationality in science and medicine. The authors, at the time doctoral students at University College London, came on board to co-design a medical history activity with the curator. We wanted to do something that would get museum visitors thinking critically about what it means to be right or wrong in medicine and how this might change with the passage of time. The result was a card game called The Unbelievable Truth of Medical History. The game challenged players to compete against one another to sort through a series of statements about theories or practices in medicine and put them into categories. They had to decide whether the theory or practice was from the history of medicine (‘past’), formed part of current understanding (‘present’) or was simply made up (‘fictional’). From floating kidneys and wandering wombs to tobacco enemas and faecal transplants, the game took players on a tour of medicine and healthcare through the ages, asking them to delineate between past and present and fact and fiction.

The game often led to surprising discoveries on the part of players. The statement ‘women have smaller brains than men’, a measurement that remains true, on average, nonetheless sparked heated discussions about how brain size was used in the nineteenth century to support pre-conceived ideas about male superiority. In contrast, the statement ‘every human personality trait corresponds to a particular part of the brain; the more you possess that trait, the bigger that part of the brain grows’ related to a historical theory, setting the scene for introducing players to phrenology. However, many attendees, at both the ‘Wrong!’ event and other events where we showcased the game, assumed that this statement described an idea from modern day neuroscience. This generated conversations, for example, about the use of imaging to connect behaviour to brain structure and how phrenology, while deemed a pseudoscience before the end of the nineteenth century, nonetheless played an important part in the history of our understanding of the brain.

These early explorations proved that the game was a simple yet effective concept and inspired us to develop a more sophisticated educational resource, re-named Mind-Boggling Medical History. While intentionally bringing to light amusing and curious ideas from medical history, the game had serious objectives: to inspire discussion about the differences between past and present ideas, and to get people thinking about what is ‘current’ and who decides this. The inclusion of the fictional category added a twist to the game, showing how it is not always easy to distinguish fact from fiction when it comes to medicine, highlighting the role of the unexpected and unlikely in medical practice. Moreover, unlike fictional theories, past practices have had real effects on patient care, and are sometimes even rehabilitated after being previously discredited. This is illustrated, for example, by the card statement ‘leeches are used to prevent soft tissue from detaching from the face in reconstructive facial surgery’ (a present-day practice), which can be used to open up conversation about the recent resurgent interest in the ancient medical method of leeching. The game thus reminds the audience that the categories are not set in stone, and that best practice in medicine and healthcare is constantly re-evaluated.

On a practical level, our early sessions indicated that this simple game, if written in accessible language and freely available for distribution, could potentially reach far wider audiences than more traditional modes of academic communication such as blogs and seminars. With this in mind, we applied to receive a grant from the AHRC Follow-on Funding for Impact and Engagement Scheme to develop the resource, which we were awarded in 2017[1]. The grant solidified our focus on adapting the game into a resource directed at two key audiences: nurses, and secondary school students working at Key Stages 3 and 4. From the outset we had considered that the game could be a good fit with nursing education at university level and in the school history curriculum through the GCSE Medicine through Time option. Our confidence in its value for nurses was increased by test sessions at the RCN’s annual congress in 2014 and 2015, a major event in the nursing calendar (our presence at which was facilitated by Sarah Chaney’s role as Events and Exhibitions Manager at the RCN). The process by which we shaped the game to also be of value to a second audience of school history students is beyond the scope of this article, in which we limit our focus to the impact of the game upon nursing. Attempting to cater to two different audiences did, however, throw up a number of issues, not least the need to limit ourselves to language and terminology that would be clear and accessible to teenagers. It also became quickly apparent from feedback from secondary school teachers that whatever kind of resource we produced, it would only be useful to teachers if there was an accompanying lesson plan to go with it; few would have time to put together their own lesson plans to support the resource. This was not necessarily the same for a nursing audience, where we found nursing librarians and lecturers often preferred to incorporate the game into existing lessons.

Fundamental to the game’s development was the involvement of the Heritage Support Group (HSG) museum consultancy. HSG work with heritage sites, museums, community groups and galleries to build capacity and skills, helping organisations plan and achieve their heritage goals. Their involvement as independent museum professionals offered a degree of consistency and standardisation to the way evaluation was carried out. It also allowed us to receive additional, expert advice from museum professionals not attached to any of the institutions invested in the game. This was especially useful given that gamification is still a novel tool in academic history settings[2]. Conversely, in recent years, the role of games and play in aiding learning has been a subject of interest within museum and information studies, in the context, for example, of interactive exhibits and in the development of apps that can connect audiences to museum collections digitally (Cawston, et al, 2017; Rodley, 2011). As the digital access librarian Bohyun Kim has described it, ‘gamification is the process of applying game-thinking and game dynamics, which make a game fun, to the non-game context in order to engage people and solve problems’ (Kim, 2013). Interestingly, there appears to be little in the literature exploring connections between gamification and participatory practice in museums. With the publication of Nina Simon’s The Participatory Museum in 2010, participation and community engagement has become an increasingly discussed aspect of museum work (Simon, 2010). Museums and museum staff aim to represent the communities they serve through collaboration and co-creation, while reflecting on and attempting to mitigate the risk of further marginalising certain groups through ‘empowerment-lite’ activities (Lynch, 2011).

Evaluating prototypes of the game

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191104/003In this project, we aimed to incorporate several, but not all the elements of participatory practice, defined by Simon as consultation, contribution, collaboration and co-creation. We consulted our target audience through focus groups at an early stage in the development process and encouraged their contributions, some of which were incorporated into the final game. During the first half of the project our chief objective was to set up and evaluate audience responses to the game via a series of small focus groups designed to gauge the opinions of nurses, teachers, museum professionals and academics. This was followed by wider playtesting with a prototype of the card game. The nursing focus group totalled eight nurses from different specialisms and stages of their career, including one nursing student, while a subsequent playtesting session at a public event at the Royal College of Nursing saw feedback collected from a further twenty people. In addition, we held a feedback session with twelve research nurses at Cambridge University Hospitals. While focus groups are an established methodology within museum practice, and indeed in other branches of research, particularly the social sciences, they tend to be less utilised by humanities academics developing public engagement activities. Focus groups can be expensive and time consuming to set up, and recruitment is not necessarily easy. In our case the institutional partnership with the Royal College of Nursing was essential in helping find nurses who were willing, interested and able to participate, especially those with teaching experience.

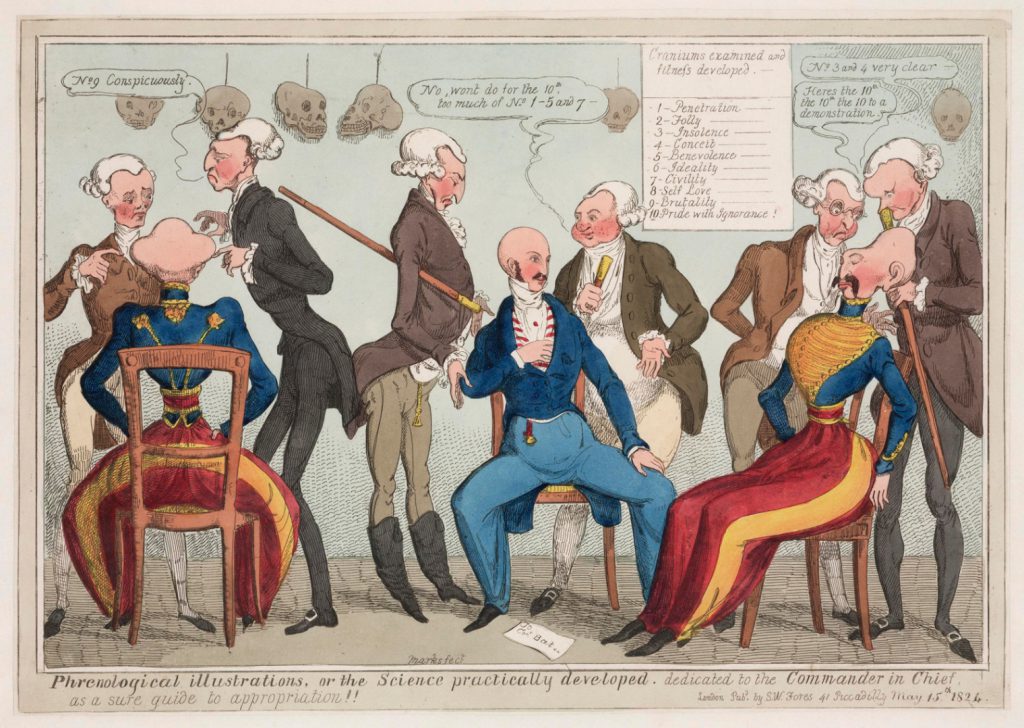

The focus groups were chiefly used to explore reactions to the game’s content and format, and whether participants felt the game was suitable for the intended audience. They proved fundamental to involving stakeholders’ voices from the beginning of the grant, particularly those in nursing education and practice. Generally, participants responded positively to the game’s flexibility, as players are free to play Mind-Boggling Medical History either as individuals or in teams, discussing each statement together, and they can also choose whether to play competitively or not. Participants also expressed enjoyment at learning new facts, found satisfaction in the speedy nature of the game, and could see its value as a tool for introducing the history of medicine. The groups and sessions also pointed us to ways we could improve the game’s structure. Based on the suggestion of both the nursing and museum focus groups we divided the fifty statement cards into five differently colour-coded themes – ‘Body’, ‘Mind’, ‘Treatment’, ‘Society’ and ‘Sex and Reproduction’ – so that players could play rounds of the game devoted to a specialist topic. Each round consisted of ten statements that then had to be sorted into the ‘past’, ‘present’ or ‘fictional’ categories. This theming of the cards made it easier for teachers and nurses to identify which subjects they wanted to focus on, and how long they wanted students to play the game for. We also designed an in-depth answer booklet so that once players had marked their answers, they could find out more about the history or research behind each statement. This was integral to ensuring discussion could continue once the game had been completed. The nursing focus groups also encouraged us to link the game directly to the curriculum, particularly by incorporating reflective practice, which encourages students to link discussion to their experiences on placement. A set of lesson plans for nursing students were created for us by nurse Hannah Little, and added to the website for anyone to freely download. In addition, the nursing focus groups strongly indicated a link between the game and the topic of evidence-based healthcare, as will be discussed below.

While the focus groups were certainly valuable to the project, incorporating participants’ feedback also highlighted a number of limitations and issues, which will be outlined in the section below focusing on the nursing audience. These issues not only impacted upon the creation of the game but also initiated an exploration on our part of a set of theoretical and practical questions as to the value of medical humanities for nurses. Some of these elements we were able to address in the project, while others suggested that, in hindsight, a different way of working with our stakeholders – in particular, involving them at an earlier stage in the development of the project, before the grant was awarded – would have been beneficial.

‘I have a problem with the “medical” word...’: nursing the medical humanities

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191104/004Museum projects dealing with medical issues have often involved doctors and, more recently, patients as collaborators. Nurses and other healthcare staff have traditionally been less involved as either participants in the curatorial process or as the focus of exhibitions.[3] In Mind-Boggling Medical History there was a lack of awareness on the part of both the game’s developers and the nurses participating in the focus groups, as to the remit and outcomes of the project at the outset. In particular, while we aimed to be consultative and encourage nursing contributions, the project was not truly collaborative. Any co-creation involved was between the university and heritage partners, not the nurse participants. Because participants were coming to a project that had already been part developed, albeit sporadically, through a number of sessions and events over several years, there was less scope to impact on the format and design of the game than some expected. This ran the risk of the coercive or rushed decision-making outlined by Bernadette Lynch, ‘manipulating a group consensus of what is inevitable, usual or expected’ (Lynch, 2011a, p 451). While we attempted to mitigate this by having a third party, HSG, lead the focus groups, ideally nursing groups should have been involved earlier in the process, before the grant application was submitted. Indeed, as we will outline below, had this been the case, the very name of the project would most likely have been different!

Arguably, the collaborative nature of the project had more impact on the authors than the participants, who approached participation as a means of challenging their own assumptions (Graham, 2016). It appeared to us that the interest in the project indicated an untapped audience, and that reasons for the lack of engagement with nurses in similar projects pointed to a deeper issue in the medical humanities. This can perhaps be best summed up by the topic that proved most controversial in our nursing focus group: the use of the term ‘medical’. One nurse objected directly to the title and stated theme of the game: ‘I have a problem with the “medical” word as it’s not representative of everything that we do as nurses and healthcare professionals’.[4] Yet, since the development of the profession in the late nineteenth century, nursing has been defined and understood by its relation to a pre-existing medical model, making the distinction between healthcare and medicine complex (Dingwall, Rafferty and Webster, 1988, p 5). Our focus group members expressed both concern about nurses’ views (they might take offence at a ‘medical’ game), and about the public perception of nursing which led to ‘misunderstandings of healthcare’.[5] From their suggestions, we broadened the topics included in the final game. Statements about the use of different types of dressings, vaccination and tuberculosis care were added as being significant elements of nursing practice and history, offering a broader realm of theories and ideas than those of biomedical practice. Despite this, naming the game and distinguishing between healthcare and medicine remained one of the most unexpectedly challenging aspects of the project. Our focus group acknowledged that nurses did need to ‘know medical ideas’ and that some nursing work was medical, however the term could not sum nursing up as a practice or profession. The project, then, highlighted a wider challenge in the definitions of modern nursing practice. Nursing includes the technical work of medicine plus something else; it is a patient-centred model of integrated care that relies on context to explain it.

This appears to be reflected in the positioning of nursing within the medical humanities. Despite the growing interest in a more inclusive discipline of health humanities (Crawford, et al, 2010), the topic still largely refers to clinical medicine. As Lise Saffran puts it, one of the fundamental claims of the medical humanities has been that using tools from humanities – narrative building, awareness of cultural context and so forth – can help increase empathy among medical practitioners; as a consequence, the medical humanities remains largely focused upon the doctor-patient relationship, exploring doctorhood, patient hood or the dialogue between the two (Saffran, 2014, p 105). This exposes a wider issue in museums of science and medicine too. Historically, it has been medical practitioners who have created medical museums, and even shaped medical history as a discipline (Arnold and Chaplin 2013, pp 232–3). The Royal College of Nursing did not even have a public museum until 2013. Some studies have indicated that nurses ‘critically curate’ the histories of their professions, for example in mental health care; however, this research is usually sociological or ethnographic, and tends to be distanced from other areas of the humanities (Holyoake, 2014).

One possible reason for the marginalisation of nursing in the medical humanities becomes apparent: if nurses are perceived already to be less aligned to science and medicine than doctors, and more to values of care, compassion and empathy, then there has been less need for tools from the humanities disciplines to be utilised in order to increase the latter in nurses. Yet the goal of many museums to follow participatory practice seems better aligned to healthcare – and health humanities – than it does to a history of biomedicine. Health humanities, Paul Crawford and colleagues suggest, can better incorporate interdisciplinarity and become a more outward-facing and applied discipline than medical humanities has historically been (Crawford, et al, 2010). As our project indicates, nurses are an important yet undervalued audience for heritage projects. Although there are certainly time and resource constraints placed on nursing engagement with museum and history projects, including the pressures of cuts to health service funding and staffing levels, the holistic view of healthcare within nursing potentially leads to an especially rich engagement between humanities researchers, heritage professionals and nurses. It offers opportunities for historical projects to have a direct impact on nursing care and practice today. In addition, such projects benefit nursing by helping to better connect nursing research with practice, supporting the profession in two goals: shaping a professional identity and promoting evidence-based practice.

Although there has been more than a century of efforts to shape professional identity, nursing leaders and organisations have struggled to define the profession. What is it that makes nursing a different field from medicine? In the nineteenth century, this was summed up in the concept of nursing as a vocation, often associated with Florence Nightingale. Nursing became viewed as a calling and desire to serve, based partly on religious ideology and partly on gendered stereotypes of women as natural carers and nursing as a preparation for motherhood (Hughes, 1990, p 26; Hallett, 2012, p 47). In contrast, figures like Ethel Bedford Fenwick claimed that nursing was a profession of equal standing to medicine, and thus focused on the similarities between the two: technical skills and a scientific background (Rafferty, 1993, p 56). These two strands of nursing remain hard to reconcile today. Clinical skills and technical expertise are easier to teach, measure and examine than the process of care itself, which may be dismissed as ‘just common sense’ (Kitson, 1993, p 26; Tierney, et al, 2016). This indicates one of the challenges for medical humanities projects to which we will return later: bridging the gap in nursing between research and theory on the one hand and practice and patient care on the other. Yet interestingly this is an issue that is also important within modern healthcare, such that health humanities can and should ‘address the nature, experience and purpose of the healthcare disciplines themselves’ (Crawford, et al, 2010, p 8).

Despite the challenges involved, this points to one of the key differences between nursing and medicine. The enormous breadth of nursing as a practice, and the complex relationships between nurse and patient and nurse and environment (whether in a hospital, home or other care setting) means that nursing as a field tends towards a more holistic and less explicitly clinical view than medicine. In her recent book exploring nursing through her own career, novelist Christie Watson noted the difference between:

What I thought nursing involved when I started: chemistry, biology, physics, pharmacology and anatomy. And what I now know to be the truth of nursing: philosophy, psychology, art, ethics and politics.

While making nursing hard to define (for historians and healthcare workers), this breadth does offer great potential for history and museum projects. With Mind-Boggling Medical History, nurses found it easy to understand the value of discussion around the topics presented, rather than viewing the game as a simple true or false dichotomy. In fact, gaming is becoming increasingly popular as a teaching method in nursing. The RCN Library includes games on dysphagia, infection control and addiction among others, often developed by hospital trusts in conjunction with companies such as Focus Games. At least one of our focus group attendees was developing her own clinical skills game for use in an NHS trust, and the project thus appealed to nurses in education and practice from a variety of angles. If anything, our nursing participants wanted to expand the focus of the game even further, raising suggestions such as wild cards (for new research that hasn’t yet made it into practice) and the inclusion of levels and layers in the explanations. This feedback helped in the development of the lesson plans, highlighting the ways in which the game could open up discussion of practice-based concerns.

While Mind-Boggling Medical History fitted comfortably into the broad remit of nursing education, the game also offered the opportunity to focus on specific areas of the curriculum. A key element was that of evidence-based healthcare, which our nursing focus group identified as especially relevant to the game.[6] Comments received from the 100 students who tried the game at RCN Congress indicated that the game helped clarify the need to keep up-to-date with medical knowledge. The concept of evidence-based medicine is usually linked to Archie Cochrane’s call for the use of randomised controlled trials to improve medical practice in the early 1970s (Cochrane, 1972). The term itself became popular in the late 1990s, and was increasingly promoted in medical education, especially with the publication of Evidence-Based Medicine: How to Practice and Teach EBM by David Sackett et al in 1997.[7] Sackett described evidence-based medicine as the method of ‘integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research’ (Sackett, et al, 1996, 71–72). The concept has become a buzzword within healthcare, even though the process by which research is linked to practice in nursing remains less well-defined than in other areas of health and medicine, due to the breadth of the nursing role. As Michael Traynor has argued, more attention needs to be paid to understanding the research and development taking place within healthcare in the context of nurses’ practices and workplaces (Traynor, 2013, pp 99–100).

Effectiveness of the game

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191104/005Our follow-up work suggests that using Mind-Boggling Medical History to make a connection between theory, evidence and practice has worked well in a nursing education setting, and the game has proven particularly popular with nursing lecturers and university librarians, as a way to introduce the searching and critical evaluation skills students need to engage with research literature. Since the full game was made available in 2018, Basildon and Thurrock University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust have used it in an induction programme to the library services for new student nurses and midwives, reaching 48 students to date. Nursing librarians use the online game as an ice breaker for students. Students choose the topic they are interested in, and library staff facilitate the session by reading the questions and going with a majority vote for the answers, following student discussion. On revealing the correct answers, staff go on to explain the role of library staff: to provide an evidence-based service for NHS workers by ensuring up-to-date material is available, facilitating access to resources and carrying out evidence searches for NHS staff to assist in safe patient care. Similar sessions have been carried out at Anglia Ruskin University and in RCN library regional support sessions around England.

The game includes specific examples of changes in best practice, which encourage discussion on the topic. For example, the statement ‘kidneys can sometimes detach from surrounding tissue and sink down into the pelvis’ allows teachers to talk about nephroptosis, a condition when the kidney drops down into the pelvis when the patient stands up, commonly known as ‘floating kidney’. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries the condition was often ‘fixed’ by a surgical procedure called nephropexy to put it back in its proper place, but the operation was dangerous and fell out of fashion. However, there has been a revival of interest in the condition in the last decades, and a laparoscopic version of nephropexy is sometimes performed today. Thus, statements help to open up conversations about how past practices may become accepted once more, influenced by new skills and technologies.

The accompanying lesson plans build upon the issue of evidence by indicating the importance of challenging outdated practices, something which speaks to the development of the nursing role from the doctor’s handmaiden to a critically autonomous professional (Hallam, 2002). The modern idea of caring as an ethical position means that nurses become viewed as advocates for the patient, something that has developed since the late 1970s. Christine Meyer gave three examples from her career in which she’d challenged a doctor’s opinion in order to support ‘the patient’s need for self-dignity and individualized care’, concluding that the ‘true professional [nurse] is one who is answerable first to herself and to her patient’ (Meyer, 1978, p 41). Christie Watson recalls being warned by another sister at her new job in a paediatric neurosurgery unit: ‘if you see a doctor using old barbaric methods of torture [to check a patient’s level of responsiveness], then stop them’ (Watson, 2018, p 135). Given the complex and unpredictable nature of modern health care, nurses are today required above all to gain the skills to ‘think for themselves rather than defer to authority’ (Traynor, 2013, pp 26–7). This critical advocacy role is a part of nursing education, and the sample lessons aimed at nursing students created as part of the project supported this, using game play to lead into discussion of situations the students had encountered on placement. This enabled them to consider as a group how new theories or research might apply in day-to-day work and whether there might be situations in which they would be expected to challenge their peers or clinical staff. As the focus group had suggested, we aimed for the game to encourage debate and questioning, and to lead students into following up the topics through research.[8]

Despite interest in the game, there have been challenges in reaching nursing audiences beyond cohorts of new students. A session at the RCN Congress for registered nurses in 2015 was considerably less well-attended than the 2014 session for students (21 attendees compared to over 100 in 2014, despite the considerably higher number of registered nurses attending overall), suggesting that professional development is not always valued once a nurse is outside an educational environment. One participant in the nursing focus group session at Cambridge University Hospitals reflected on this: staff may struggle to recognise the relevance of research within a pressured hospital environment. As part of a large team in Accident & Emergency, she was nonetheless the only nurse who attended research seminars and set an explicit value on understanding research in order to improve her knowledge and skills as a nurse. Other staff, including managers, took a more pragmatic approach, only wanting to learn things that would be immediately useful to them. This caused a shift away from evidence-based practice, creating a responsive model of nursing based on technical skills. Indeed, there is a wider perception that this responsive ‘common sense’ view of care can be problematic, for ‘it is extremely difficult to give good care. Compassion and intelligence may be innate, but empathy, good judgement, up-to-date knowledge and the ability to make independent decisions are attributes most of us have to learn.’[9] Care, we would argue, cannot be dismissed simply as common sense, but needs to be valued as something that requires ongoing learning and support throughout a nurse’s career.

Conclusion

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191104/006Mind-Boggling Medical History was launched in February 2018 with a physical card pack, initially available for free to those working in education, nursing, public engagement and museums, as well as an (Packman, et al, p 377). Mind-Boggling Medical History suggests ways in which the medical humanities, and medical and healthcare history in particular, can be impactful upon clinical practice, in ways other than emphasising empathy or creativity in practitioners; instead it shows how the discipline might usefully contribute to professional development and evidence-based practice. In turn, museums would benefit from the greater opportunity for funding and in-depth research to underpin their exhibitions and other activities. Involving stakeholders from the very beginning of an academic engagement project has significant benefits for the output, as well as enabling participants to learn from each other throughout. In this project, not only did the focus groups help to shape the associated material (instructions, answer books and lesson plans), but our engagement with nurses shaped the content of the game itself, making it a better fit for nursing students. Had we involved audiences at an even earlier stage, during the writing of the grant itself, we might have become aware much earlier of the need to address the distinctions between healthcare and medicine, something that became of significant importance to the project.

Working with nurses on this project inspired the authors to critically reflect on a number of issues around public engagement projects, and even the content and scope of the medical humanities as a discipline. We discovered that, despite prior assumptions about the lack of time available and the scope of the nursing role, nurses did wish to engage in a project that was not directly relevant to their practice and tended to look positively on a critical attitude towards healthcare practice. The way in which the game encouraged both reflection and awareness of the changing nature of clinical theories appealed to nurses and fitted well into nursing education. However, for some nurses in hospital practice, using the game as a route into in-depth research was more problematic, and research still seemed quite distant from their day-to-day work. The biggest challenge, however, was the way in which the game had been framed medically: as reflected in the title ‘Mind-boggling Medical History’. Nurses wanted something that addressed healthcare more broadly and did not imply that nursing was merely a sub-category of medicine. However, what exactly this wider nursing remit might be was much harder to pin down, other than in concepts like ‘reflective practice’ or the broad category of care. The slippery definition of nursing that emerged has lengthy historical roots, which drew the authors’ attention to the distinctions between nursing history and medical history; between medical humanities and health humanities. It did also, however, indicate a much greater potential for engaging nurses in museum and humanities projects, with benefits on both sides that may range beyond the initial project itself to the definition and shaping of the very field of research and practice.

Acknowledgments

Our colleagues on Mind-Boggling Medical History were Sally Shuttleworth (University of Oxford), Daniel Burt (Sunnymedia Ltd), Mary Chapman (University of Leeds), Frances Reed (RCN), Anna Semmens (RCN) and Sarah Green (University of Oxford). Heritage Support Group are Debbie Shipton and Cara Sutherland. Teaching resources were created by Clare Hartnett and Hannah Little. Additional statement writing was provided by Molly Case and Sarah Punshon. Thanks also to the History of Science Museum, Oxford, the Learning Resources and Curatorial team at the Science Museum, the School of History, Queen Mary, University of London, and everyone who participated in focus groups and playtesting for the game. We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Arts and Humanities Research Council.

Thanks to Frances Reed, Anna Semmens, the Diseases of Modern Life team at the University of Oxford and our two reviewers for their helpful and insightful feedback on earlier drafts of this paper.

Tags

Footnotes

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text