The Indian challenge and the rise of Manchester

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/231907

Keywords

Cotton textiles, India, Industrial revolution, industrialisation, Manchester

Introduction, by Sally MacDonald, Director Science and Industry Museum, Manchester

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/231907This essay was delivered as a keynote presentation by Professor Prasannan Parthasarathi at a conference, Historical Threads, held at Manchester’s Science and Industry Museum in November 2022. Up to that point, many of us in the audience had probably felt reasonably knowledgeable about the role of cotton production in the growth of Manchester and in what we call the Industrial Revolution. This essay was a revelation, presenting an entirely new, global perspective on the long history of international cotton trading, and positioning Manchester’s growth as a competitive response to what had for centuries been an Indian success story; one that was swiftly rewritten by nineteenth century British historians and industrialists.

This museum has for over thirty years featured a much-loved Textiles Gallery, highlighting regional innovations, such as Richard Arkwright’s water frame, and the global and social impact of industrialisation and mass production methods developed in and around Manchester. But we have never told the story that is told in this essay, nor properly framed Manchester’s growth within a world context. The museum, as part of the Science Museum Group, is now committed to presenting more inclusive narratives, developing displays to feature previously untold stories and provide global perspectives. There are few more painful or problematic histories than that of the cotton trade, and this conference was a first step towards creating a ‘Cottonopolis’ gallery, which will set Manchester’s textile history in a bigger, harsher yet ultimately richer context. This essay is a first step towards that retelling.

Note: Professor Parthasarathi is the first in a series of keynote speakers who will be invited to give presentations on subjects crucial to the Group’s major projects or research themes and whose lectures will be published in the Science Museum Group Journal.

Note: Professor Parthasarathi is the first in a series of keynote speakers who will be invited to give presentations on subjects crucial to the Group’s major projects or research themes and whose lectures will be made available online and published in the Science Museum Group Journal.

The Indian challenge

In the early twentieth century cotton was by far the most important textile fibre in the world. In 1913 (as can be seen from Table 1) cotton accounted for 80 per cent of world fibre consumption. Wool was a distant second at 16 per cent and silk, linen and hemp together accounted for a mere 4 per cent. Cotton did not lose its commanding position till the post-war period when synthetics such as polyester began to grow in popularity. Nevertheless, even in 1990, cotton represented 48 per cent of the world fibre market (Coleman, 2003, p 939).

| Fibre | Proportion of total consumption |

| Cotton | 80 % |

| Wool | 16 % |

| Others (silk, linen, hemp, etc.) | 4 % |

Table 1: World Fibre Consumption, 1913 (Coleman, 2003, p 939)

Traditionally, cotton’s global ascendancy has been attributed to the rise of Manchester and the British Industrial Revolution. In this argument the late eighteenth-century invention of machines such as Arkwright’s water frame made Lancashire the workshop of the world. Cotton was the backbone of Britain’s nineteenth-century industrial might. In Eric Hobsbawm’s famous words: ‘Whoever says Industrial Revolution says cotton’ (Hobsbawm, 1999, p 34).

In this paper, however, I will argue that the ascendancy of cotton pre-dates the rise of Manchester, and that the Indian subcontinent is critical to that pre-history. Indian cotton textiles were consumed globally long before Lancashire became the workshop of the world. That pre-history forces us to rethink the rise of Manchester. We must view Manchester in a global framework and see its rise as a response to an Indian challenge. In other words, regional or national frameworks are not sufficient to understand developments in the eighteenth century.

Here I suggest that readers take away two things. The first is an appreciation for cotton’s long history and the second is a global perspective on textile manufacturing and innovation in eighteenth-century Manchester.

The spread of Indian cotton

The Indian subcontinent had exported cotton textiles since at least the time of ancient Rome. Textual sources tell us that Romans admired and appreciated what appears to be Indian cotton cloth. An ancient trade link between Rome and India has been confirmed with the discovery of Roman coin hoards in a number of locations, including South India – and these discoveries point to a second feature of the trade in Indian cotton cloth: those who wanted it had to bring gold and silver with them to India (Warmington, 1928, pp 210–12, 273–318).

In medieval times, Indian cottons travelled on the Silk Road and the historian Stephen Dale has even proposed that these trade routes be renamed the Cotton Road because of the volume of Indian cottons that were carried on them (Dale, 2009, pp 79–88). Indian cottons moved on water as well as land, the most famous being the thriving trade in the Indian Ocean. Geographically, the Indian subcontinent lay at the centre of this ocean. Economically, it was the centre as well and Indian cotton cloth was demanded all along its shores.

East Africa had long been a market for Indian cottons and continued to be well into the twentieth century. From the coast, the cloth was carried to the interior where it was used as a form of currency. Demand for this cloth made it possible for Indian rulers to field armies of enslaved soldiers. According to one historian, ‘African manpower was extracted and exported in exchange mainly for Indian textiles’ (Eaton, 2005, pp 107–112).[1]

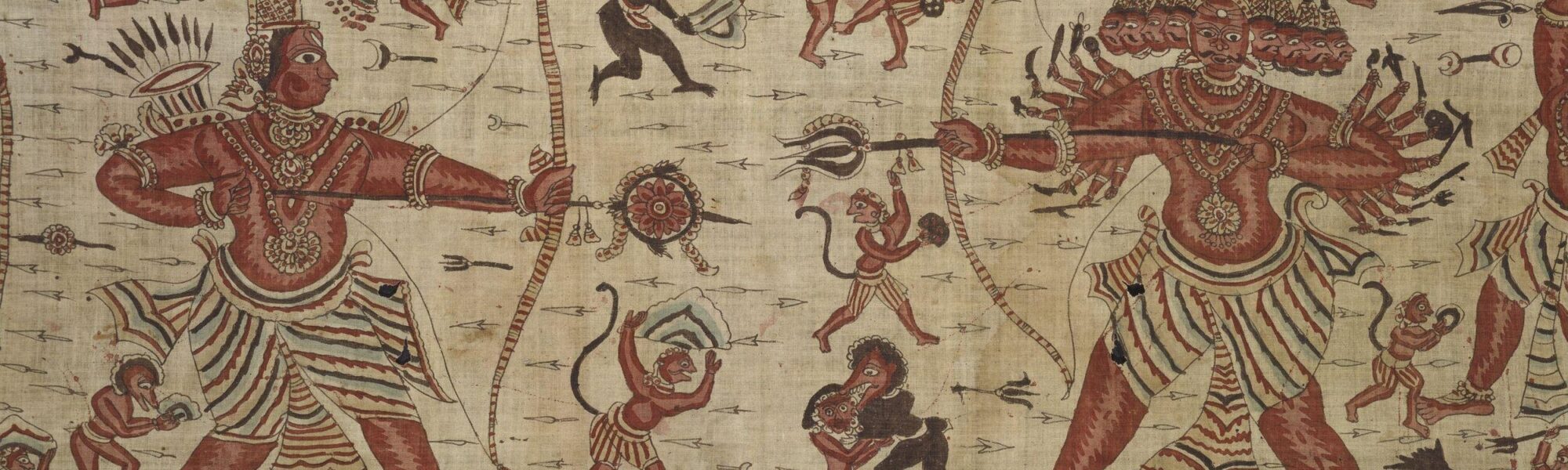

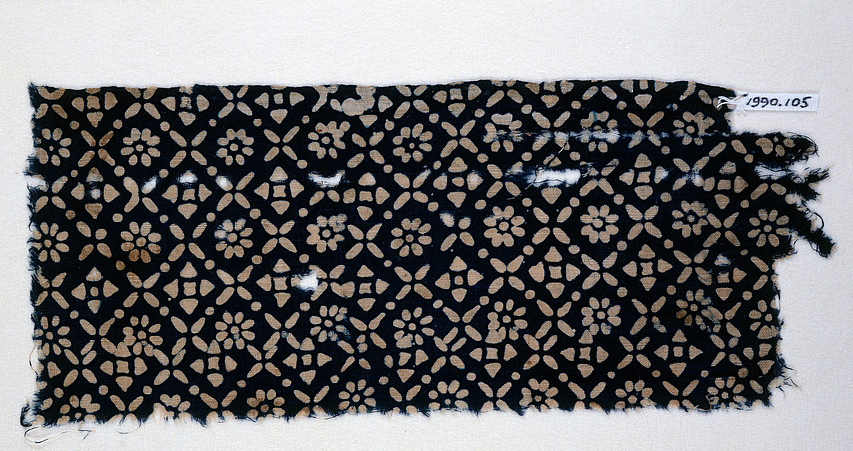

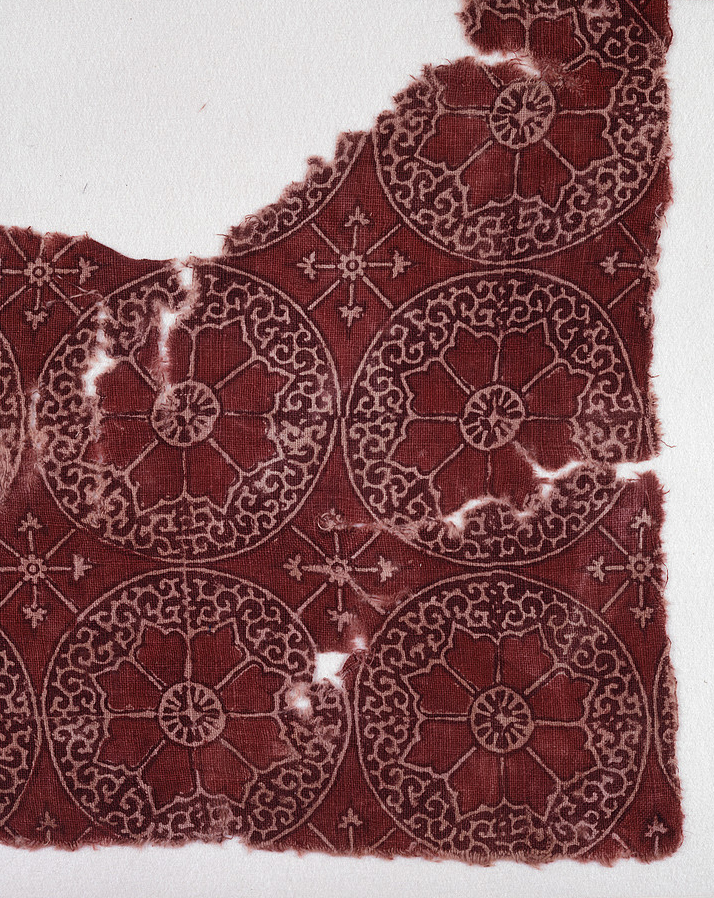

From the eighth century, Egypt was home to avid consumers of Indian cottons. We know this from fragments of cloth that were discovered in Fustat, the old city of Cairo, in the early twentieth century. (These fragments have been dated to between the eighth and sixteenth centuries.) The Ashmolean Museum in Oxford possesses a large collection of these textiles and a few examples are given in Figures 1–4. Much of the Fustat cloth was of low to middling quality – definitely not a luxury item. How do we know this? First, the cloth is not hand-painted but printed, which is a less expensive process. Some examples of painted cloth are presented later in this paper and the difference in fineness and workmanship is apparent. Second, the cloth was printed in two or three colours, which requires fewer steps than cloth with several colours, and is again less expensive.

These fragments had been in museum collections for some years and their provenance was unclear. In the 1930s, the great textile scholar Rudolf Pfister connected these cloths to the Gujarat region of western India on the basis of art and architectural evidence. Others who saw these Fustat fragments were struck by the duck pattern, which they had seen in Indian cloth elsewhere. Figure 5 gives an example of an Indian cloth made in Gujarat in western India for the Southeast Asian market in the late fifteenth or early sixteenth century. And we see that the Fustat duck in Figure 6 is identical to the Southeast Asian duck in Figure 7. The duck design allowed scholars to identify Gujarat as the place of manufacture.

And the duck was not the only design that cloth buyers in both Egypt and Southeast Asia appreciated. Figures 8 and 9 illustrate a floral pattern that was found on cloth in both places. In the early sixteenth century, the Portuguese adventurer, Tomé Pires, wrote that Cambay, the great port of Gujarat, ‘stretches out her two arms, with her right arm she reaches out toward Aden [near the entrance to the Red Sea] and with the other towards Malacca [in Southeast Asia]…the trade of Cambay is extensive and comprises cloths of many kinds’.[2] With these textiles from Egypt and Southeast Asia, we have material confirmation for Tome Pires’s observation.

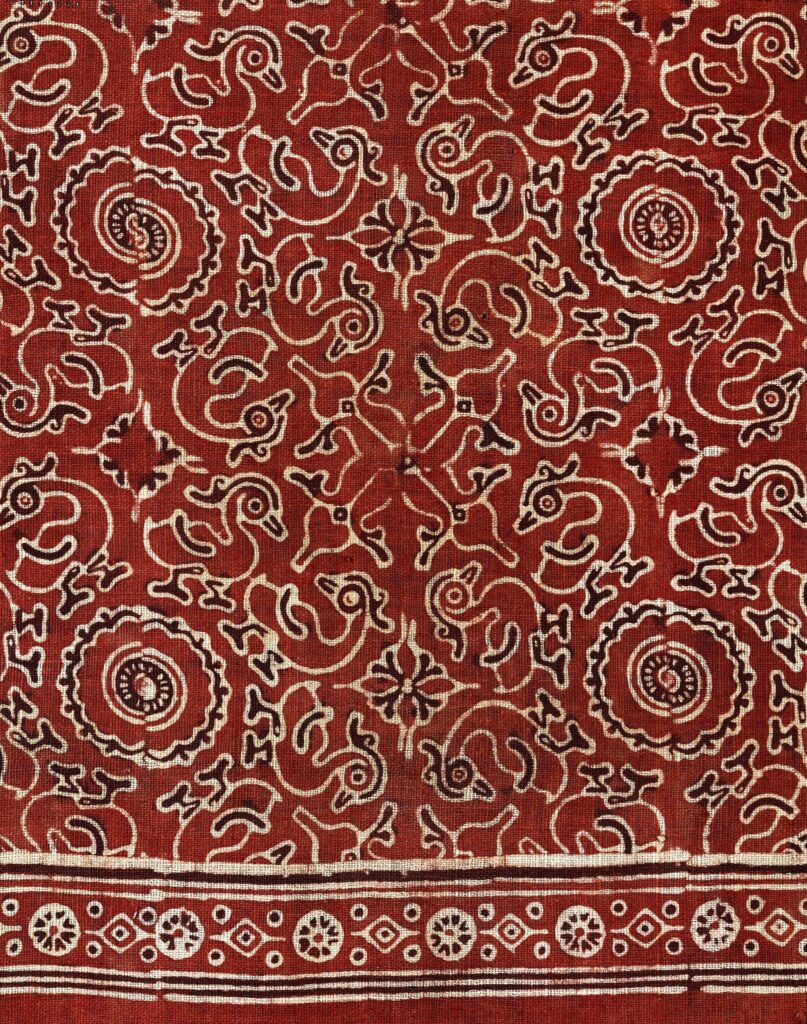

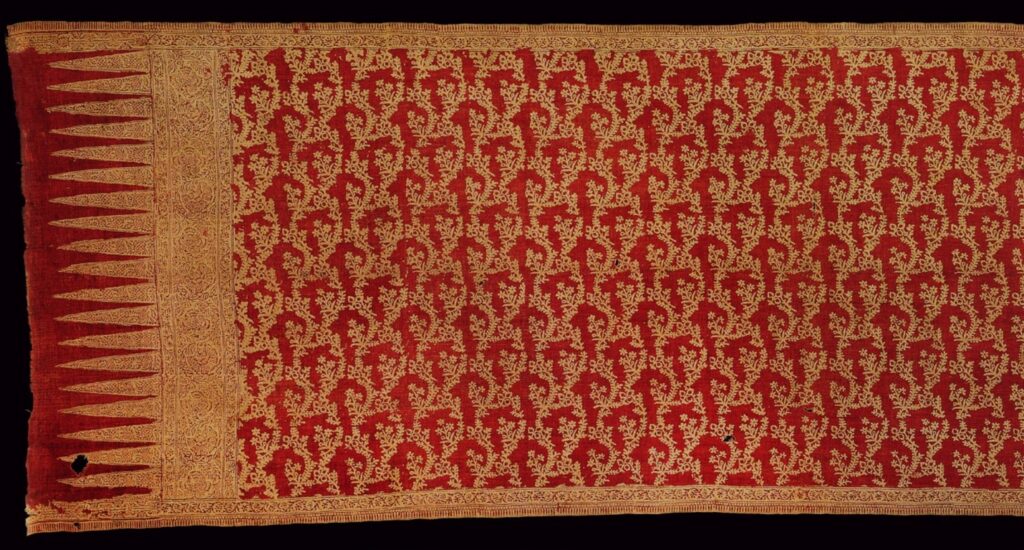

Southeast Asia consumed a wide variety of Indian cloths. Figure 10 gives an excellent example of a waistcloth made in India and exported to that region. This cloth would not have been terribly expensive. It was block-printed and contains only two colours. There is no denying the great beauty of the piece. However, its workmanship cannot be compared to that of a hand-painted waistcloth, also made in India for the Southeast market, which is given in Figure 11. The fine details and multiple colours mark this as an exquisite piece. John Guy writes that the cloth ‘illustrates the consummate skill of the cloth painters of the Coromandel Coast [in Southeastern India]. The highly refined control of line, combined with a heightened sense of colour, achieves a vitality rarely seen’ (Guy, 1998, p 39).

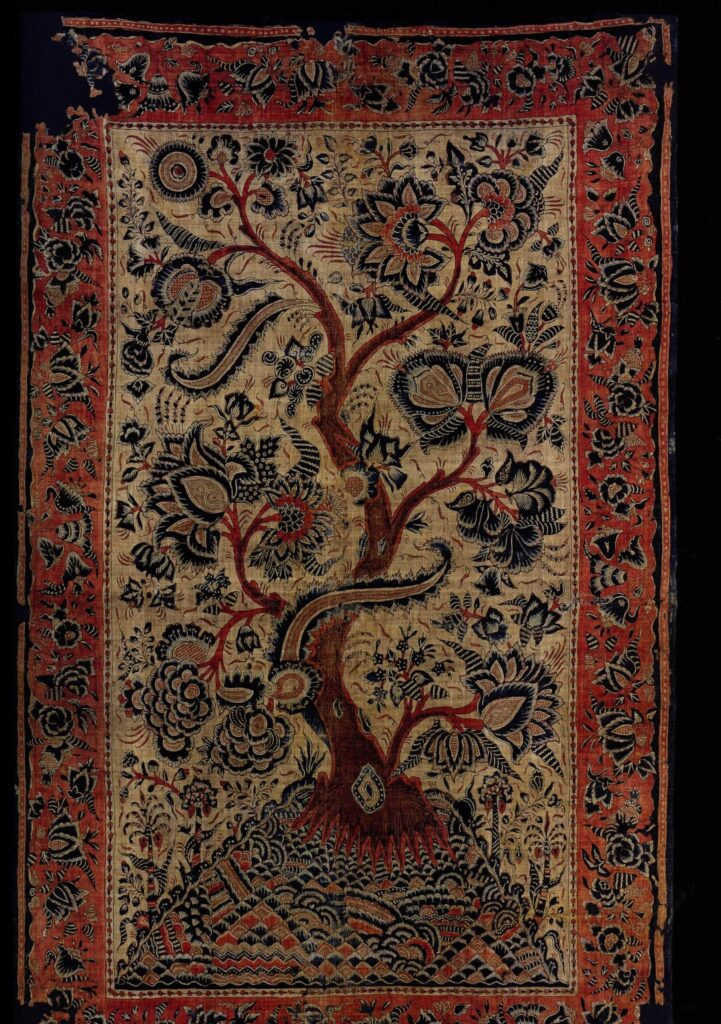

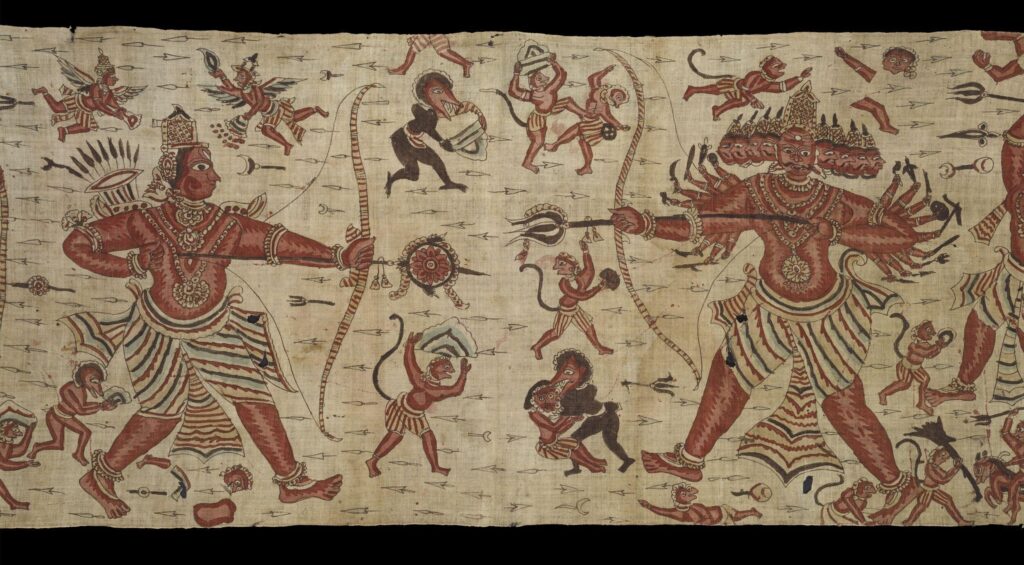

Indian cottons were also used in Southeast Asia for decorative and ceremonial purposes. Figure 12 illustrates a tree of life that was made in Southeastern India. The damage to the four corners, especially the top left, suggests that it had been used as a canopy. The corners were damaged when the cloth was affixed to four poles. Indian cloth also provided a backdrop for the recounting of stories and epics, as may be seen in Figure 13. This cloth made for the Southeast Asian market contains characters and scenes from the great Indian epic, the Ramayana. Rama is on the left and his nemesis, the ten-headed demon Ravana, on the right. About a dozen of these Ramayana cloths have survived and it would be interesting to make a comparative study of them.

Indian cotton cloth reached East Asia as well. While China was not much of a market for these textiles, they were prized in Japan. This can be seen in Figure 14 in which Indian printed cottons were used to assemble an underrobe.

Cotton trade with the Americas and Europe

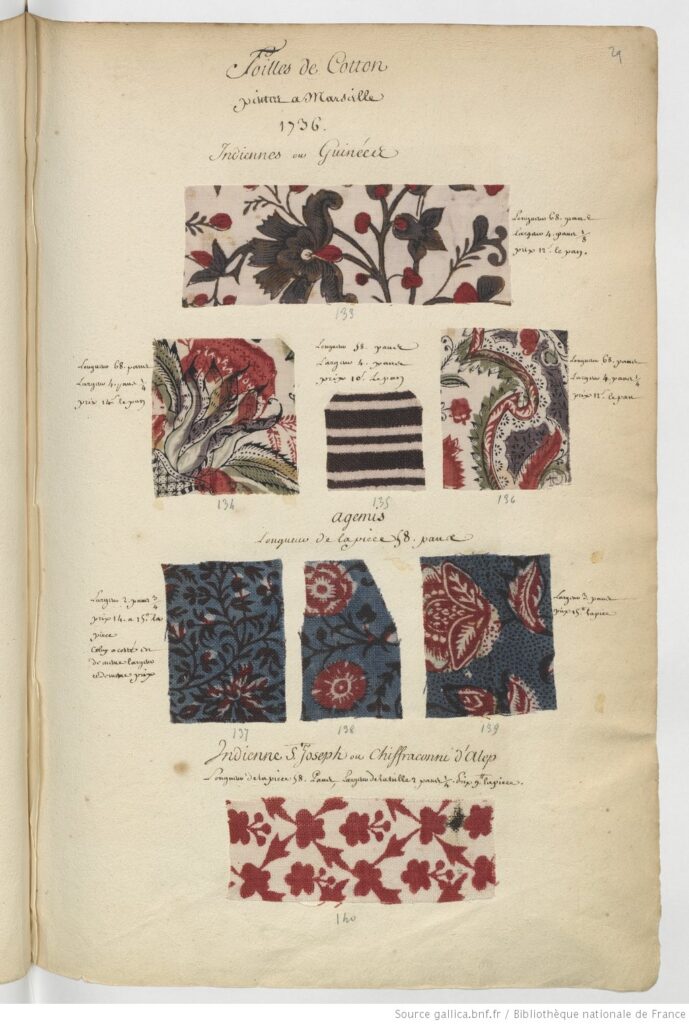

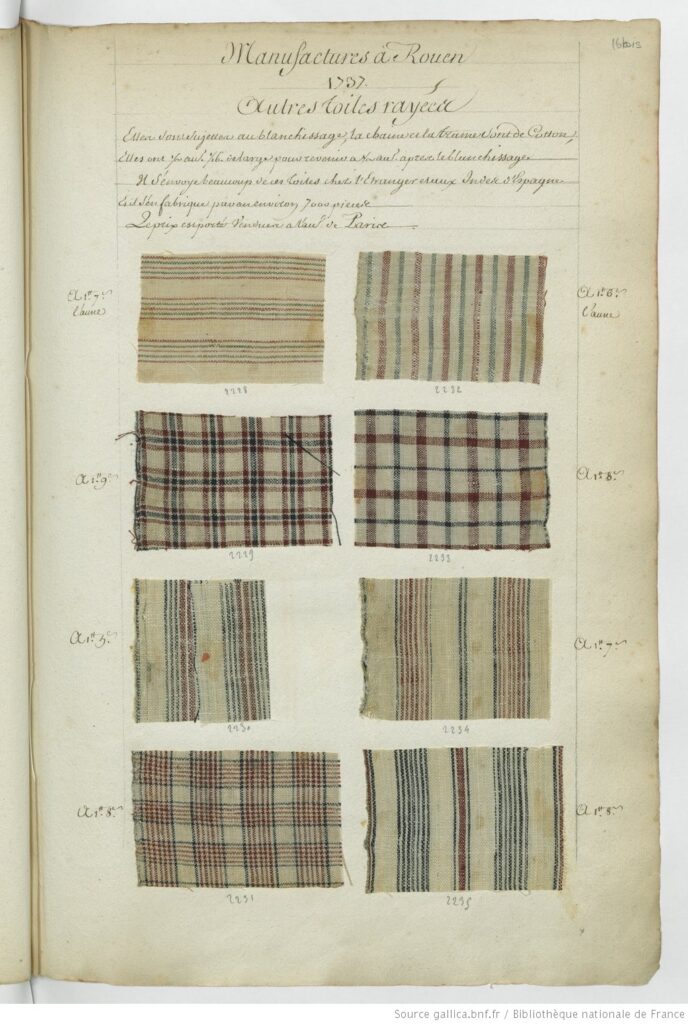

From the sixteenth century, Indian cotton cloths made their way to the trading world of the Atlantic. These textiles found appreciative buyers in West Africa (some Indian cottons may have reached that region from East Africa even before Europeans rounded the Cape of Good Hope). But by the eighteenth century the West African appetite for these cotton textiles seemed insatiable. Between 1700 and 1806, when the British outlawed the trade, Indian cotton cloth represented a third of the goods that British traders exchanged for enslaved men, women and children on the West African coast (Johnson, 1990, pp 28–29). To put this figure into perspective, Indian cottons were used to purchase two million men, women and children in the eighteenth century (the peak period for this trade). French sample books give us an idea of the florals, checks and stripes that West Africans demanded and two examples are given in Figures 15 and 16. Some of these cloths were made in Rouen and Marseilles.

Indian cottons clothed some of these enslaved individuals when they reached the Americas. High status enslaved men and women – managers, drivers, head housekeepers and nurses at times – received cotton for their dress while the bulk of the enslaved wore less expensive and more durable linens and woollens (DuPlessis, 2009, pp 227–46; DuPlessis, 2015).

However, Indian cottons diffused widely among European settlers and free people in North and South America too. Europeans took to the cloth. They made shirts from them (as seen in Figure 17); they made skirts from them; they made gowns from them (which can be seen in the painting of free women in the West Indies in Figure 18); and they made coats or banyans from them in Spanish America (see Figure 19).

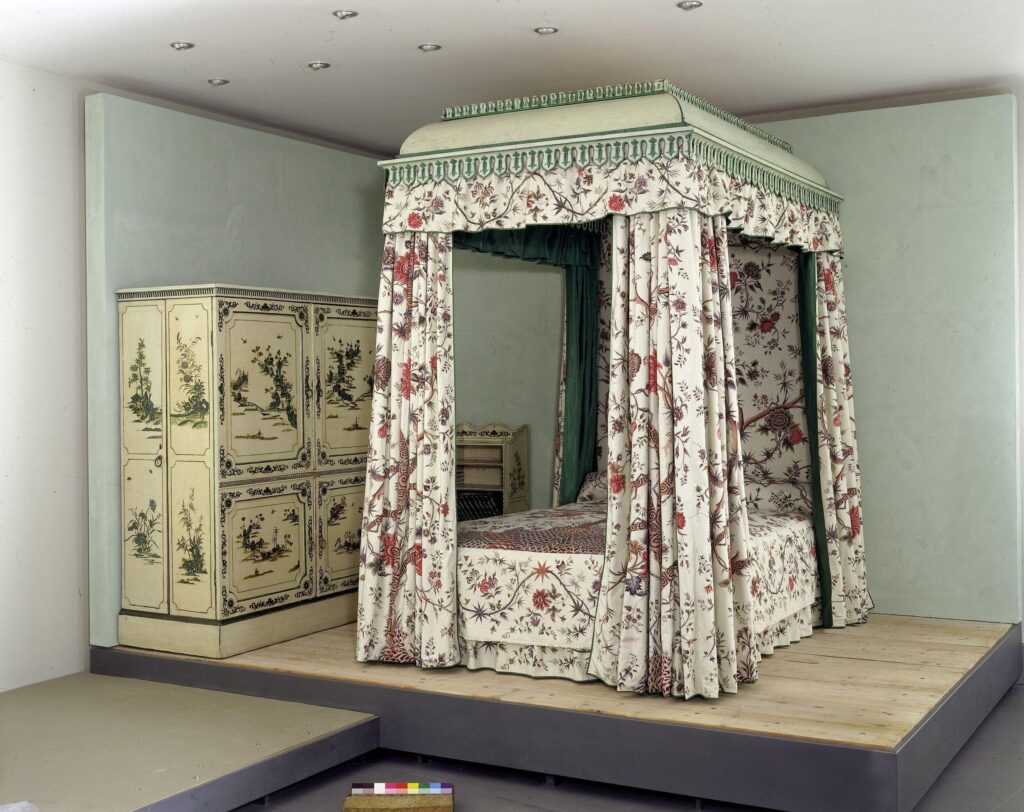

Finally, from the mid to late-seventeenth century, there was growing demand for Indian cottons in Europe itself. This was the famous calico craze. In a few decades, Indian cloth seemed to be everywhere. In 1727, an anonymous London writer wrote: ‘On a sudden we saw all our women, rich and poor, cloath’d in Callico, printed and painted; the gayer and the more tawdry the better’ (Thomas, 1963, p 26). And more ominously: ‘It crept into our houses, our closets, and bedchambers; curtains, cushions, chairs, and at last beds themselves were nothing but Callicoes or Indian stuffs’ (Ibid, p 30). As is evident from these passages, the European response to Indian cottons was decidedly mixed.

Those concerned with the maintenance of status hierarchies disliked the social levelling that the Indian cloth made possible. Now a strawberry seller could wear a cotton gown that resembled the silk gown of a lady, but at a fraction of the cost, as Beverly Lemire has taught us (Lemire, 1991).

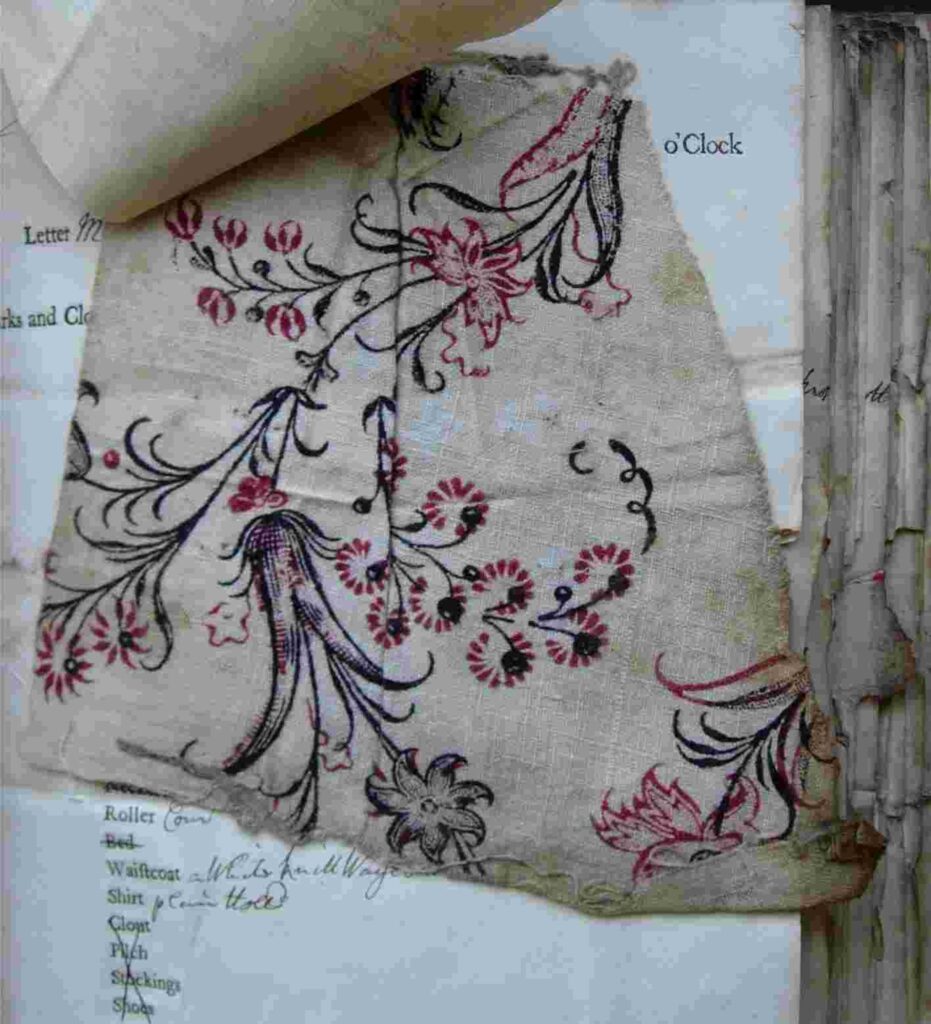

The desire for cotton cloth reached the bottom rungs of the social hierarchy as can be seen from Figure 20, which comes from the London Foundling Hospital. When foundlings were brought to the hospital, the admission was registered and a piece of the infant or child’s clothing was clipped off and attached to that document as a way of identifying the foundling. A number of these fragments were cotton (or mixtures of cotton and linen – I will discuss mixed cloth shortly). But since these foundlings tended to come from poorer backgrounds, the cloth was usually of poorer quality. The coarseness of the piece shown in Figure 20 is obvious. It was a cloth that was not printed properly and the red petals do not line up with the centres of the flowers. But this was what this foundling’s family could afford.

Cottons remade the domestic interior in eighteenth-century Britain. Figure 21 shows the famous Garrick bed from the Victoria and Albert Museum. Recall that our anonymous commentator complained that Indian cotton ‘crept into our houses, our closets, and bedchambers…and at last beds themselves were nothing but Callicoes or Indian stuffs’.

The calico craze did not grip only Britain. In eighteenth-century France cotton cloth became a larger component of dress for all social classes. Table 2 gives the proportion of clothing items made from cotton in the wardrobes of several groups in French society. The top line is for 1700 and the bottom for 1789. There are two things to note about this table. First, the proportion of cottons in wardrobes for all social groups went up in the eighteenth century. In 1700, cottons comprised less than 8 per cent of clothing items. In 1789, cottons ranged from 20 per cent to 40 per cent. Second, the most dramatic increases in cotton consumption were among the working classes. While noble people increased their proportion of cottons from 7 per cent of clothing items to 25 per cent, consumption among domestic servants went from 7 per cent to 40 per cent. Wage-earners and artisans and shopkeepers witnessed similar increases. The availability of cotton cloth gave working people access to lighter cloths that had been the fashion in western Europe for many decades.

| Nobilities | Domestics | Wage-earners | Artisans and shopkeepers | Professions | |

| 1700 | 7 % | 7 % | 7 % | 8 % | 3 % |

| 1789 | 25 % | 40 % | 38 % | 39 % | 20 % |

Table 2: Cotton consumption in eighteenth-century France (cotton garments as a proportion of all garments)

Source: Daniel Roche, The Culture of Clothing: Dress and Fashion in the Ancien Regime, trans. Jean Birrell (Cambridge, 1994), pp 127, 138

Indian cottons were popular across the world for a number of reasons. They were light and comfortable, especially when worn next to the skin. This quality continues to account for cotton’s popularity today. Indian cotton cloth was also colourful and colourfast. This was a testimony to the skill and knowledge of Indian craftsmen who had perfected a range of dyes and mordants to fix those colours to the cloth. While animal fibres take and hold colour more easily, plant fibres are notoriously difficult to dye. Indian cottons gave consumers colourful cloth that was more comfortable than wool and less expensive than silk. Finally, these cloths were washable. And repeated washings did not lead to the colours fading; if anything, they were made more brilliant.

For these reasons, cotton became fashionable all over the world. What this evidence suggests is that there was a global cotton revolution that predated the rise of Manchester. The cotton manufacturers of India – spinners, weavers, dyers, cloth printers and painters – lay at the centre of this cotton revolution. Their skill, knowledge and ability to adapt their cloths and designs to meet the tastes of a diverse clientele made that revolution possible. Sophisticated merchant networks (and these were Asian, European, African and American) transmitted information on changes in tastes, for fashions were not fixed but constantly in flux, to cloth manufactures in India. Although few of these have survived, merchants and their agents had sample books that recorded the designs that were in demand in different markets.

The role of silver from the Americas

Finally, we must not ignore the role of silver from the Americas. Precious metals were the commodities that Indians most demanded from the outside world. There was little desire for manufactures, even though the English East India Company kept trying to sell wool cloth in places like Madras (now Chennai), where I am from in South India. Madras is reputed to have three seasons: hot, hotter and hottest. As you can imagine, there was little demand for wool in that tropical climate.

American silver fuelled the Indian cotton revolution and made it possible for buyers around the world to consume the cloth. One historian has estimated that between 1600 and 1800 about a quarter of the silver mined in the Americas ended up in India. Much of this silver, as well as some gold, was made into coins and fuelled an extraordinary commercialisation of the Indian economy. In the eighteenth century the advanced commercial regions of India were quite possibly the most monetised areas of the world (Parthasarathi, 2011, pp 46–50).

Across the world, the outflow of silver to India created economic hardship. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries the Ottoman Empire suffered from a constant drain of silver to India. This led to shortages of specie for minting money (Inalcik, 1993, p 272). And in Europe scores of writers complained of the loss of precious metals to the East and criticised the trade of the East India Companies.[3]

To stem the loss of silver and gold, and to seize upon lucrative trading opportunities, cloth manufacturers around the world turned their hands to imitating Indian cloth. In some cases, these imitations copied Indian designs. Figure 22 is a cloth from the seventeenth or eighteenth century printed in South India for the southeast Asian market. Next to it in Figure 23 is a cloth manufactured in Indonesia in the early twentieth century. As you can see the design effects are similar.

In the Ottoman Empire, cloth printing was done in imitation of Indian printed textiles. Some of the cloth was consumed locally and some exported to Russia, eastern and central Europe and even France. These cloths were known as Indiennes Constantinople, which identified them as Indian printed cloth made in the Ottoman lands. There were several centres for the manufacture of these Indiennes Constantinople, including Bursa, Tokat and Diyarbakir (Fukasawa, 1987).

Efforts to print cotton cloth in the Indian style migrated from the Ottoman Empire to Europe itself (and here Armenians were important in transmitting knowledge on dyeing and printing techniques). Calico printing workshops arose in a number of European cities. In the seventeenth century they were found in London, Amersfoort, Berlin, Frankfurt, Hamburg, Bremen, Neuchatel, Lausanne and Geneva. In the eighteenth century they had expanded to Dublin, Antwerp, Stockholm, Copenhagen, Barcelona, Vienna, Munich, St Petersburg, Moscow, Prague and Nuremberg (Parthasarathi, 2011, pp 46–50).

Indian cloth and the rise of Manchester

The most important efforts to imitate Indian cloth took place in Manchester and its surroundings. These efforts were so consequential because they gave rise to major technological breakthroughs such as Richard Arkwright’s water frame and Samuel Crompton’s mule. With these machines, the centre of global textile manufacturing shifted from India to western Europe.

For many decades, these innovations were believed to have emerged as a response to shortages of yarn. Eric Hobsbawm wrote in his classic work, Industry and Empire, ‘As every schoolchild knows, the technical problem which determined the nature of mechanization in the cotton industry was the imbalance between the efficiency of spinning and weaving’ (Hobsbawm, 1999, p 34). The imbalance stemmed from the fact that it took at least three spinners working fulltime to supply sufficient yarn for one weaver. The supply of yarn became a bottleneck and limited the size of the textile industry.

Even if few mainstream economic historians subscribe to this explanation today (many of them are content to follow the lead of Robert Allen and attribute textile innovation to high English wages, which is also problematic) (Allen, 2009). Nevertheless, the yarn shortage explanation continues to endure and it is still found in textbooks and in popular and journalistic writings. For instance, in 2013, the archaeologist and textile authority, Elizabeth Wayland Barber, wrote in the New York Times, ‘Lack of thread for the weavers…led to some of the most important machines of the Industrial Revolution, such as the spinning jenny’ (Wayland Barber, 2013) .

There is a problem with this explanation, however. No one in eighteenth century Britain cites it as the driver of innovation in textiles. My research suggests that yarn shortages were first given as an explanation in the early nineteenth century. It appears in Richard Guest’s Compendious History of the Cotton Manufacture, published in 1823. I will return to Guest shortly, but first, what do eighteenth century voices tell us?

These voices tell us that the problem that manufacturers in Manchester faced was not the quantity of yarn – it was the quality. And Indian cotton cloth was the measure by which the yarn spun in Manchester was judged. Indian cottons set the quality standard.

Before I expand on these two points, let me give you a sense of the markets that Manchester supplied in the first several decades of the eighteenth century. In these markets, Manchester manufacturers competed against Indian cottons.

First, there was a market within Britain itself. Restrictions on the import of Indian cotton cloth shaped this market. In 1700, the import of printed and painted cloth from India was prohibited and this gave a great push to the British printing industry, which grew rapidly. The raw material for these printers was plain white cloth from India, but in 1720 the import of this plain cloth was prohibited. The drive to restrict Indian cloth came from a broad constituency who feared the loss of livelihoods and included silk weavers in London and wool interests across the realm (Thomas, 1963, p 26).

The ban on printing on Indian white cloth, save for export, led British manufacturers to search for a locally made substitute. In the 1730s, these cotton entrepreneurs settled upon a light cloth that was a mixture of linen and cotton. Cotton was used in the weft – the cross-yarns that the weaver inserted by throwing the shuttle. Linen was used as the warp (the yarns that are fixed in the loom and stretched taut). Thus, importantly, in the 1730s the best substitute for Indian cotton cloth that Manchester came up with was a mixture of cotton and linen. We will return to this point (Parthasarathi, 2011, pp 46–50).

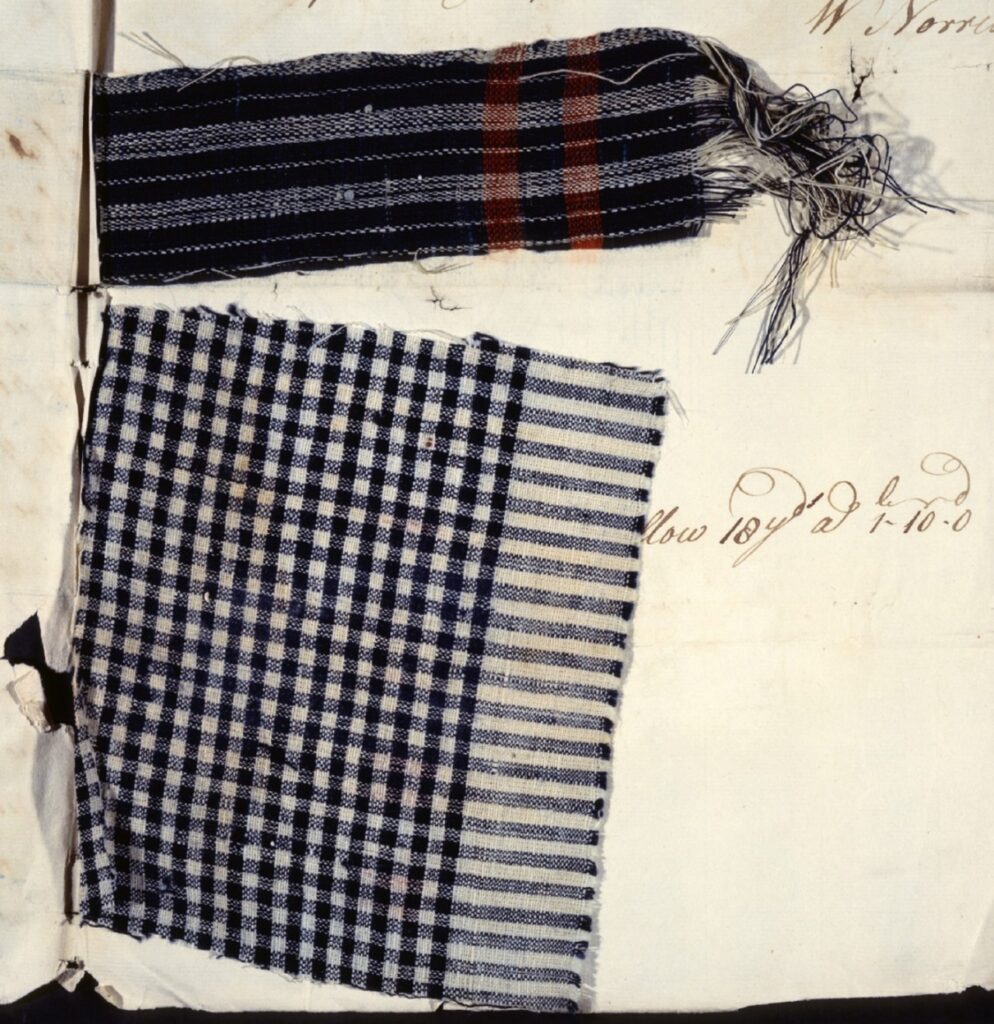

Second, Manchester manufacturers supplied markets in the Atlantic world. These included North America and the Caribbean where the demand for cotton goods grew rapidly in the eighteenth century. Manchester cottons also supplied the slave-trading ships that sailed from London, Liverpool and Bristol. Figure 24 shows swatches of striped and checked cloth that a manufacturer in Blackburn attached to a letter that he sent in 1751 to the Company of Merchants Trading to Africa. He included these swatches as examples of the cloth he could supply. They served as proof of the quality of his wares, which he claimed were the equal of Indian goods.[4]

Once again, we find that Indian cloth set the standard of quality for the cloth masters of Manchester. For much of the eighteenth century, however, Manchester could not match Indian cloth for the simple reason that its textiles were a mixture of linen and cotton. These cloths did not feel like the all-cotton cloth from India. They did not smell like them, they did not wash like them, and they did not look like them because the two fibres, linen and cotton, took dyes differently, making dyed and printed cloth splotchy and the colour uneven (Parthasarathi, 2011, pp 46–50).

It was not the quantity of yarn that Manchester masters worried about. It was the quality. The problem they faced was how to make a cotton yarn that was strong enough to be stretched to form the warp. If they could do this, Manchester could make an all-cotton cloth that matched the Indian.

The problem of yarn quantity is what preoccupied Samuel Crompton, the inventor of the mule. This is of course the spinning technology that came to dominate the spinning mills of Manchester for many decades. Near the end of his life Crompton had occasion to reflect on his invention and the history of the cotton manufacture in Lancashire. He wrote: ‘About the year 1772 I began to endeavour to find out if possible a better method of making cotton yarn than was then in general use being grieved at the bad yarn I had to weave’.[5]

Richard Arkwright, the inventor of the water frame, praised the machine for making it possible to spin cotton yarn that was suitable for the warp. Arkwright wrote of the water frame: ‘Warp, made of Cotton which is manufactured in this Kingdom, will be introduced in the Room of the Warps before used, made of Linen Yarn in making Lancashire Cottons…Goods so made wholly of Cotton will be greatly superior in Quality to the present Species of Cotton Goods made with Linen Yarn Warps, and will bleach, print, wash and wear better’.[6]

And in 1780, an anonymous pamphleteer in Manchester, writing under the pseudonym ‘A Friend of the Poor’, made the connection between the Indian challenge and the rise of Manchester explicitly. He wrote, ‘When I look upon our machines…my heart glows… Perhaps, by new improvements, we may vie with the East-India goods in fineness and beauty’ (Anon, 1780, p 16).

A new interpretation of the past

In the nineteenth-century histories, the Indian challenge receded into the background and the pivotal role that Indian cottons had played in the rise of Manchester was slowly forgotten. Inventive activity in spinning began to be understood as a response to shortages of yarn. Richard Guest, a historian of the Manchester cotton industry was the first to write of yarn as a bottleneck. He wrote in his Compendious History of the Cotton Manufacture, published in 1823, that a weaver was forced to walk ‘three or four miles in a morning, and call on five or six spinners, before he could collect weft to serve him for the remainder of the day; and when he wished to weave a piece in shorter time than usual, a new ribbon or gown, was necessary to quicken the exertions of the spinner’. According to Guest, this led to a search for a machine that could increase the supply of yarn.

For Richard Guest, innovation in spinning emerged from the forces of supply and demand. Yarn shortages were a signal to potential innovators to develop new technologies (Guest, 1823, pp 12–13).

In 1815, eight years before Guest published his history, John Kennedy, a co-founder of the celebrated Manchester firm, Kennedy and McConnell, also attributed innovation to the operation of supply and demand. In his lecture, entitled ‘Observations on the Rise and Progress of the Cotton Trade’, which he delivered on 3 November 1815 at the Literary and Philosophical Society of Manchester, Kennedy gave a concise account of the rise of cotton in Manchester. I read this pamphlet at the Manchester Central Library some twenty years ago and it was a pivotal moment in my research. It is now available online.[7]

In his observations, Kennedy divided the progress of the cotton trade into four phases. In phase one, there was an expansion of the market for cloth at home and abroad and this widened the demand for cottons. With this expanded market, there was an extension of the division of labour, which marked phase two of the progress of the cotton trade. Manufacturing steps that had been done by a single worker were now subdivided and distributed among several workers. This increased the efficiency of the manufacture. In phase three, this subdivision and specialisation led to improvements in technique. In some cases, these improvements led, in phase four of the progress of cotton, to the invention of machinery itself. With this account, Kennedy has given a market-centred explanation for the rise of Manchester. There is no Indian challenge. There is no state policies of protection. It is a market driven process of change.

The framework that Kennedy laid out may be familiar to readers. This is the scheme of economic progress that Adam Smith gave in Book One of his great work, the Wealth of Nations. There Smith wrote that ‘the invention of all those machines by which labour is so much facilitated and abridged, seems to have been originally owing to the division of labour’ (Smith, 1976, p 20). And the extent of the division of labour is determined by the extent of the market. Kennedy applied this Smithian framework to explain the rise of Manchester.

This reinterpretation of the rise of Manchester, and here I refer to the shift from the challenge of Indian quality to the operation of the market, happened at the precise moment when Manchester’s manufacturers shifted from being proponents of a mercantilist state, and protection from Indian competition, to champions of free trade. We have seen that the Indian challenge led to a series of state prohibitions on Indian cloth imports. This happened in 1700 and 1720, but the final act of restriction was in the 1780s when the cotton manufacturers of Britain successfully lobbied parliament for a high tariff on Indian muslins. Muslins had previously been allowed to be imported freely, but Crompton’s mule had made a British muslin manufacture possible. The challenge of Indian quality demanded the intervention of the state even in the late eighteenth century.[8]

The tariff on Indian muslins was the final act in Manchester’s mercantilist phase. From the 1790s, the cotton masters of Lancashire moved towards free trade. In that decade, the cotton men opposed restrictions on the export of yarn, which weaving interests had proposed. The export of yarn reduced supply and raised prices for weavers but widened demand which benefitted spinning interests, and spinning is what dominated in Manchester at that time. In 1812, when the English East India Company charter was up for renewal, the cotton men of Manchester opposed the Company’s monopoly on trade to the lands that lay east of the Cape of Good Hope. The cotton men viewed those areas as potential markets for their wares and wanted to have open access to them. The free trade era in Manchester had been inaugurated (Parthasarathi, 2011, pp 46–50).

This shift in economic philosophy led to a rewriting of the story of cottons and the history of Manchester’s rise. The commitment to free trade produced accounts that were consistent with the commitment to the market and to the beneficial effects of supply and demand. That shortages in yarn propelled technological innovation in spinning fit with the new free trade stance of Manchester. It became the conventional wisdom when Edward Baines, Jr enshrined it in his authoritative History of the Cotton Manufacture in Great Britain, which was published in 1835. Baines was the most important nineteenth century historian of cotton and he recognised that India was the ‘birthplace of the Cotton Manufacture’, while Britain was the ‘second birthplace of the art’. When it came to the invention of spinning machinery, however, Baines forgot India and the problem became one of chronic shortages in yarn. This led the weaver to continually press upon the spinner and spurred the invention of machines that relieved yarn shortfalls (Baines, 1835, pp 6, 76–7, 81).

Recent research adds exciting, new evidence in support of the connection I have drawn between the Indian challenge and the rise of Manchester. I refer to the work of Alka Raman, who completed her PhD in economic history at the London School of Economics in 2021.

Dr Raman literally put pieces of British and Indian cotton cloth under the microscope to assess the quality of these textiles (Raman, 2022, pp 447–474). The samples that she analysed came from the Barbara Johnson, the John Holker, and the John Forbes Watson collections. The Barbara Johnson album is a scrapbook of the textiles that Johnson wore from 1746, when she was eight years old, till her death in 1823. The album is now in the Victoria and Albert Museum and it provides an unparalleled window into the dress of a middle-class woman in those decades. The John Holker manuscript is largely a compilation of cotton cloths that were manufactured in and around Manchester in 1750 and 1751. It was an act of industrial espionage for Holker compiled this information for presentation to Marc Morel, the inspector of cotton manufactures in Rouen. Holker showcased the best British cotton manufactures of the day, for his aim was to receive French support for a cotton enterprise in Rouen, and this he received in 1752. The John Forbes Watson collection, which consists of 18 volumes, drew upon the textile collection of the India Museum to show British manufacturers the types of cloth that Indian consumers demanded. Forbes Watson assembled the volumes in 1866 and they give a snapshot of Indian textile manufactures before the industrial era. Twenty sets were made of these volumes and they were distributed across Britain and India.

Dr Raman selected 434 samples from these collections and determined the quality of each piece. The chief measure of quality was threads per inch, or TPI, which is an indication of the fineness of the yarn. The higher the TPI, the finer the yarn. Dr Raman drew two conclusions from her analysis. First, the quality of British cotton cloth improved steadily between the mid-eighteenth century and the early nineteenth. This conclusion was based on the materials in the Barbara Johnson Album. (The quality of the Holker samples matched that of the mid-eighteenth-century swatches in the Johnson collection.)

Second, despite this improvement in quality, even by the nineteenth century the best British cloth still could not match the muslins in the Forbes Watson collection. Manchester made tremendous technical progress between the 1740s and 1820s but had not caught up to the textile workers of India. I should add that Forbes Watson excluded samples of very fine cloth from his collection because he did not believe British manufacturers had a competitive edge in that segment of the market. Forbes Watson himself did some microscopic analyses of Indian and British muslins and documented the superiority of Indian yarn in fineness and strength. This made it possible for Indians to weave a finer and more durable cloth. The Indian challenge gave rise to the Manchester cotton revolution, but that challenge began in the seventeenth century and stretched well into the nineteenth.

Conclusion

In What is History?, E H Carr argued that history is a dialogue between the present and the past. ‘We can view the past, and achieve our understanding of the past, only through the eyes of the present,’ Carr said (Carr, 1961, p 28). This is one of the reasons that history is always being rewritten. The concerns of the present change and this leads to new interpretive frameworks and to new questions about the past. History writing is a dialogue between the present and the past and in this paper I have discussed several such dialogues.

In eighteenth-century Manchester, it was widely understood that the problem of Indian quality propelled the development of the cotton manufacture. And that problem of quality required the protection and support of a mercantilist state. These facts shaped historical reflections on the rise of cotton in Manchester.

From the 1790s, the cotton masters of Lancashire shifted from protection to free trade. In this new economic climate, the logic of the market and the forces of supply and demand were believed to have shaped the development of cotton. The market histories of cotton took several forms, but the most enduring was a framework that saw the great eighteenth century innovations in spinning as a response to shortages of yarn. Quantity replaced quality.

The argument that I have presented here, that the Indian challenge was critical to the rise of Manchester, is very much a product of our times. We live in an era of the global. We are global citizens. We breath the air of global competition. And we live in an era in which India is a rising power. The ‘Indian challenge and the rise of Manchester’ began with these realities. It is a history for the twenty-first century.