A history of ourselves?

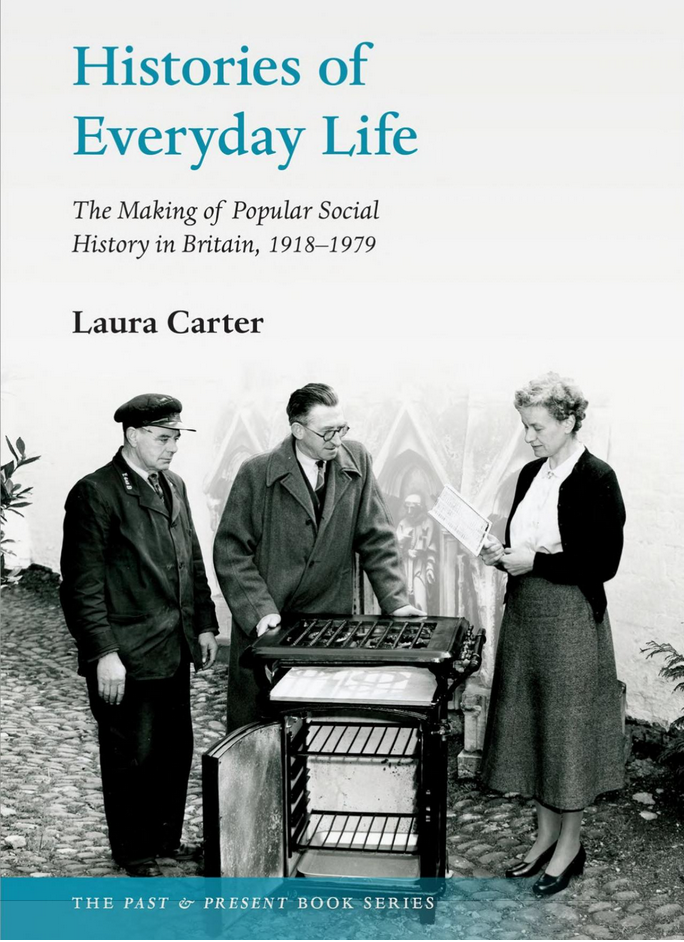

Book review: Histories of Everyday Life: The Making of Popular Social History in Britain, 1918–1979, by Laura Carter, The Past and Present Book Series (Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 2021), 288pp, ISBN 978-0-19-886833-0, Hardback, £81

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/232011

The everyday is a powerful idea, a seemingly self-evident category to which several generations of museum curators have turned; a route to audience-sensitivity as we seek to domesticate the unfamiliar; a reason for acquisitions or a taxonomical heading to order collections; and – above all – an appealing subject for displays. Laura Carter’s quietly brilliant recent book, Histories of Everyday Life, helps us to understand why this category might seem so commonsensical to any of us born before about 1970, and quite how contingent on a hundred-year history that is.

Carter convincingly shows how, across the media of popular publishing, radio, school teaching and museums, the history of everyday life became a significant subject of concern for more than half a century from the First World War, a period that she dubs ‘the educational century’. The history of everyday life was a variety of social historical practice developed outside the universities and significantly broader and richer than G M Trevelyan’s famous negative definition of social history as ‘the history of a people with the politics left out’ (Trevelyan, 1944). In her definition,

the “history of everyday life” was a pedagogical construct, created and disseminated as a form of popular social history for “ordinary” people in the mid-20th century…a new form of social history for less able pupils, soon-to-be “ordinary” citizens (p 3).

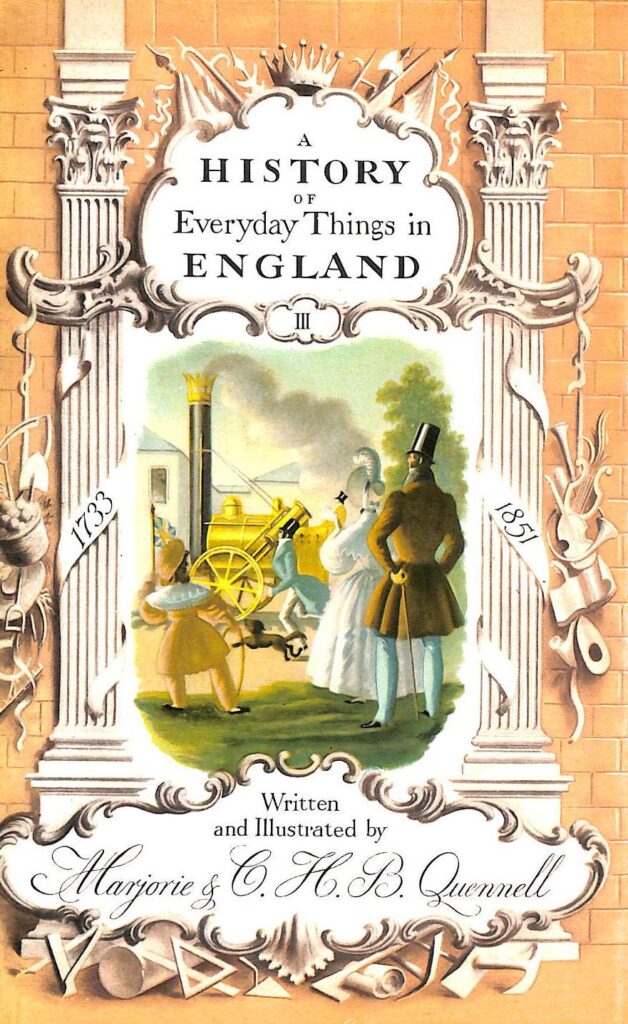

Making frequent appearances in these pages are Marjorie and Peter Quennell, whose four-volume series A History of Everyday Things in England (published 1918–1934) is emblematic of the whole field, and on whom Carter has already published (Carter, 2016).

What makes her account so compelling is that she is able to demonstrate the presence of similar tropes across all the medial locations she explores. These include the centrality of woman practitioners, a local-historical emphasis, a stress on individuals rather than social groups, and a focus on ‘ordinary’ people both as subjects and as audiences for everyday life history. The breadth and depth of Carter’s reading is formidable; any one of her chapters could readily become a book in its own right, but the virtue of having them together under ‘one roof’, as it were, is the way that it allows the category to shine through.

Carter is very clear that the specific educational culture in which this variety of history prospered gave particular opportunities and agency to woman practitioners. As she argues, ‘if we are to fully comprehend the contribution of women to public life in Britain after 1918 a profound new appreciation of this educational culture is essential, including its connection to cultural industries, voluntarism, and local politics’ (p 114). Accordingly, amongst her players we find in addition to Marjorie Quennell, the Power sisters (historian Eileen and radio producer Rhoda); the local museum curators Enid Porter (Cambridge Folk Museum), Isabel Grant (Highland Folk Museum) and, in the post-1939 museum context, Molly Harrison (Geffrye Museum). This kind of history rejected the constitutional discipline’s stress on kings and queens, parliaments and wars and emphasised instead the domestic and unexceptional lived experience of ‘ordinary’ people, especially women. And this word ‘ordinary’ was a core part of their lexicon, in terms of how these practitioners thought of both their subject and their audiences.

Intriguingly, we learn in this volume of serious attempts over several decades to create a national English everyday life history museum inspired by Skansen in Stockholm: a pre-First World War plan for a national folk museum in the Crystal Palace got nowhere, but Wales got St Fagans (1948) and Northern Ireland its folk museum (1964). The generality of everyday history or folk museums, however, fell much more in the sphere of local government and Carter discusses examples in Luton, Cambridge, York and the Scottish Highlands. There was a sense of the distinctiveness of place in this endeavour that, as in Patrick Gedde’s Cities in Evolution (1915), emphasised the particularity of local industries, such as straw hat-making in Luton. This same localism created a space for the history of everyday life in school education in the long period before the national curriculum (1988+) when responsibility was delegated to local government, Local Education Authorities and to a diversity of regional examination boards. Everyday life history was seen as relatable for less academic pupils, as it stressed the familiar. This provided an opportunity for local museums, as well as for schools, to provide services particularly for children.

Carter argues that ‘there was an idiosyncratic synergy between progressive educational techniques for ordinary consumers of history and conservative impulses focussed on individual and individualistic responses to history’ (p 141). The tradition of the history of everyday life that Carter delineates was most often associated with non-élite audiences. She argues that,

the “history of everyday life”, with its premium on usability and practical skills, became a tool for teaching history to the ordinary modern pupil, whose mind allegedly requires references to real life situations [and this] informed justifications for popular social history in all cultural spheres in the mid 20th century (p 15).

And so we see this kind of history being taught in Secondary Modern schools after the implementation of the 1944 Education Act, but not in Grammars. And in comprehensive education this kind of history was favoured for the earlier secondary years, and for the lower level CSE, rather than the ‘O’ Level curriculum. A similar stratification in BBC radio meant that everyday life histories were favoured for programming on the Home Service, with more academic programming on the minority audience culture and music Third Programme. The working-class local community of Hoxton – including, until the Second World War, a lingering community of furniture makers – was seen to require a kind of everyday domestic history. Thus Marjorie Quennell and Molly Harrison – successive curators of the Geffrye Museum from the mid 1930s – recast the Museum’s room sets, originally placed on show under an Arts and Crafts Movement stress on craftsmanship of production, as spaces for visitors’ imaginative reconstruction of historical past lives. In the postwar consumer boom, Harrison took this even further away from production into use by programming some of the Museum’s activities around histories of taste.

Carter shows that the tradition to which she devotes her book was quite distinct from the later more leftist – and often more masculine – kind of social history academic practice of the late 1960s associated with E P Thompson’s The Making of the English Working Class (1968). Here, Carter argues (p 239), academic social science disciplines, including sociology and anthropology, had serious influence. This later social history ‘foregrounded the suffering and trauma of past injustices, vocalised by a generation of educated, politically aware, male class warriors’ (p 240). But, as she shows in her final chapter concentrating on history teaching in mixed ability comprehensive schools, the history of everyday life in her sense was not snuffed-out by new academic discourse. Rather, it failed as a pedagogical focus in mixed ability secondary school teaching, and was unable to address issues of power in the context of the multiculturalism of post-Windrush Britain.

Everyday life and Science Museum curation

Charles Madge described Mass Observation, another twentieth-century practice deeply concerned with everyday life, as ‘an anthropology of ourselves’. Punning on this, I use ‘A history of ourselves’, the title of this review also to refer to our curatorial selves. Carter can be seen as revealing an important aspect of the genealogy of our own practice, of the ‘conditions of possibility’ within which we work. Quoting Carolyn Steedman, she suggests that students encountering the new social history at the Robbins-era universities may well have experienced it through the lens of the older history of everyday life (p 240). In the same way, curators arriving to work in museums in the half-century since then have probably unknowingly carried a mix of the old and new social histories with them, especially if they have been keen museum goers. I would argue that this has relevance for us now, not only in our treatment of the past, but in the transfer of social historical modes to the present in contemporary collecting initiatives, for example. Here the acquisition of ordinary mass-produced items to signify aspects of contemporary experience – a notable recent example being the Covid pandemic – rests on the foundation that the ordinary is worthy of memorial, in the traditions that Carter describes.

This is an important part of the history of the culture that made us the social history curators we are. But our practice is also strongly shaped by the collections we have inherited, which may variously have been collected under the Museum’s interwar developmental ethos (Boon, 2023), the faux-anthropological ambitions of Henry Wellcome (Skinner, 1986), or the traditions so well illuminated in Histories of Everyday Life. But even when we depart from the kinds of tradition that are the principal concerns of Carter’s book, our curatorial practices, perhaps especially in the unconscious sense, act in an echoing dialectic with our predecessors’ beliefs. So we may not be enacting a localised, volkish, feminised mode of curatorship when we seek to invert authoritarian modes by emphasising the contribution of marginalised voices, but in a sense when we do so we may well be virtue-signalling that we are not doing the older kind of social history.

And, of course, the distinction between the everyday and the iconic is often at work in our own practice. I should declare an interest here: I was the eminence grise behind the ‘technology in everyday life’ displays that occupy the northern side of the Making the Modern World gallery, also curating the third of five displays, concerned with the late nineteenth–mid twentieth century period. Here the motivation was to deconstruct the remnants of ‘great man’ history (Ashworth, 2014) embodied in the ‘icons’ of technology in the centre of the gallery by placing them in comparison with a ‘history from below’ enacted through commonplace objects from the Museum’s collection.

If the cultural history of Histories of Everyday Life provides one key to unlock the museum ‘practice of everyday life’, it is not the only one, because everyday life is a topic for analysis under many schemas. I have written elsewhere about Michel de Certeau’s very different work under that title, which opens the door of everyday life onto a very different vista (de Certeau, 1984). De Certeau’s is a cultural theory of ordinary practice, not a history of everyday things. And yet the spatiality of his account is very congenial to the analysis of museum display and practice, including – self-referentially – that concerned with the everyday (Boon, 2011). And of course everyday life is also the subject of many compilations and meta-analyses across art history, sociology, anthropology as well as history (see, for example, Kaplan And Ross, 1987; Gardiner, 2000; Sheringham, 2006).

The Science Museum does not feature in this book; indeed, as we have seen, part of Laura Carter’s argument is that in museum practice, everyday life history flourished away from the metropolitan centre and the national museums. But the extent to which the Science Museum partook of the priorities, aesthetic and practice of the broader sector – as discussed in her two chapters about museum practice – is a valuable index of this Museum’s relationship to broader museum culture. It is notable, for example, that the Science Museum opted to create and display a new collection of domestic technology in 1973 as part of its postwar turn to ‘the general visitor’.[1] Having read this book, it becomes impossible not to see our own Museum’s history in a new light. For example, Glimpses of Medical History, the first gallery display of the newly arrived Wellcome medical collection in 1980, adopted the room set technique of the Geffrye and other social history museums. By comparison, the second gallery, The Science and Art of Medicine, displayed thousands of objects in conventional showcases within a specialism-sensitive medical-historical layout. Was this division reproducing the Secondary Modern/Grammar School or Home Service/Third Programme distinctions of everyday life history? For anyone trying to answer any such a question, Laura Carter’s book will be essential reading.