‘Everything passes, except the past’: reviewing the renovated Royal Museum of Central Africa (RMCA)

Keywords

Central Africa, decolonial approaches, Democratic Republic of the Congo, museum interpretation, Royal Museum of Central Africa

Introduction

Decolonisation has been a global hot topic for museums over the last few years, whether through educational movements such as #Rhodesmustfall (Rhodes Must Fall, 2015), museum displays such as Birmingham Museum’s The Past is Now (Birmingham Museums), archival work such as the Pitt Rivers’ ‘Labelling matters’ project (Museum Next, 2019) or the New York Museum movements of ‘Decolonize Brooklyn Museum’ and #Decolonizethisplace (Decolonize This Place, 2018). Belgium is also no stranger to these discussions: in 2013 The Royal Museum of Central Africa (RMCA) closed its doors in order to renovate and revisit the colonial content and buildings of the Museum. Located in the municipality of Tervuren (just outside Brussels), the RMCA reopened in December 2018 aiming to ‘present a contemporary and decolonised vision of Africa’ through its galleries (RMCA, 2018a). The following article describes the author’s impressions of the new gallery. It discusses the successes and failures of this project, as well as its implications for UK museums.

It is useful to first understand the meaning of colonisation and decolonisation within the context of museums. Whilst the literature on decolonisation is too extensive to be fully engaged with here, there are many texts which discuss the topic in detail.[1] As S A Saggar, author of the Decolonial Dictionary writes, ‘In the context of…current conversations around decolonisation in museums and wider society…[colonisation] refers to the European imperial project, and its offshoots in settler societies’. The definition also mentions that ‘whilst direct colonial rule over parts of the world was a historical project, we continue to live with these inheritances today, both in metropolitan centres and former colonies’ (Saagar, 2019). Decolonisation for museums often refers to the attempts made by historical institutions to change the negative inheritances and power imbalances of colonisation. Thus far, decolonial approaches within UK museums have often been limited to partial changes to a building, rather than a complete overhaul of the entire museum space. Temporary exhibitions, community outreach and workshop spaces are the most common attempts at decolonisation made by UK museums, though there have been calls throughout the industry for a bolder approach to the decolonising process. Sharon Heal, the Director of the Museums Association, encouraged museums in her article Who’s afraid of decolonisation? to ‘collectively stop making excuses’ and to embrace the ‘new narratives’ that decolonisation presents (Heal, 2019). Though work is being done within the UK to decolonise spaces, there is still more to do for sustained change to happen. Hence RMCA makes an important case study for the complete renovation of large colonial European museums. This article will assess how successful the RMCA has been in its aims to decolonise a colonial museum. After outlining the origins of the RMCA the paper will review the newly refurbished Museum, and then reflect upon the legacies and lessons learnt through this ‘decolonising’ project.

The significance of the RMCA example

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191213/001There were several reasons behind my visit to the new RMCA. Firstly, I wanted to experience a museum entirely dedicated to African content. With a total of 11,000m2 of space accessible to the public, the RMCA is one of the largest museums dedicated to Africa in the world. There is no permanent museum space within the UK which is solely dedicated to telling the stories of Africa and or the African diaspora (let alone Central Africa). Hence the RMCA provides an example of what a museum focused on the stories of the African diaspora in the UK could look like. Secondly, since the Museum’s creation in 1898 the RMCA has always been a dual museum and scientific institute, and ‘even today, two thirds of the staff and the budget of the Africa Museum are dedicated to scientific research’ (RMCA, 2018b). The connections between science and colonialism have been historically downplayed. With many science institutions viewing themselves as purveyors of scientific truths, rather than acknowledging the biases they hold whilst undertaking scientific practice. Ethnographic museums are often singled out as institutions which hold the most visible links to practices of colonialism. This, however, lulls non-ethnographic institutions into a false security, and it is important to acknowledge the ways in which science (art, and other discipline-led museums) have been used to empower and legitimise colonial attitudes within Belgium. Thirdly I wanted to assess the effectiveness of the decolonisation of the space, for me personally as a visitor of African heritage, but also as an exemplar for other museums. What can Britain learn from the remodelling of the RMCA? Will it be possible to duplicate a similar process in Britain’s colonial institutions? My final motivation related more generally to learning about Belgian-Congolese relations and history. Having visited Belgium the year before the new museum opened, I had seen countless examples of King Leopold’s wealth all over the capital city. King Leopold personally oversaw the colonisation of the Congo (known then – rather ironically – as the Congo Free State), which involved pillaging Congolese wealth before the country was annexed by Belgium in 1908. How would the 8–10 million people killed by Leopold’s regime be respected and memorialised throughout the museum? (Hochschild, 2012, p 3). I hoped that I would be shown signs of Central African resilience throughout the ‘decolonised’ RMCA space.

The history of the RMCA

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191213/002

Colloquially known as ‘The Africa Museum’, the Royal Museum for Central Africa was founded from the colonial section of the Brussels International Exposition of 1897. Looking at the Museum’s history with a twenty-first century gaze, it can be seen that the Exposition was created as a propaganda tool, used by Belgian colonialists to display plundered Congolese objects and even including a fake African village (in which Congolese peoples were displayed like spectacles in a human zoo).[2] King Leopold II’s creation of a museum in Tervuren allowed the transfer of the temporary colonial exhibition to a permanent space, justifying Leopold’s colonial endeavours to Belgian and international audiences for years to come. While highly unacceptable to society now this process was not unique in nineteenth-century Europe. Drawing comparisons with the UK, both the Science Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum were founded upon the collections from the Great Exhibition of 1851, which was actively supported and driven by another Royal family member – Prince Albert. The land for the South Kensington museums is to this day frequently referred to as ‘Albertopolis’, and the museums on Exhibition Road are intrinsically linked to Imperial history through Prince Albert’s extensive support for the Great Exhibition and the creation of the South Kensington ‘cultural zone’ (museums, Imperial College, the Royal Albert Hall), which followed from it. Historically museums have upheld knowledge holding and knowledge-producing roles within society. As institutions they often separate themselves from the impact and long-lasting effects of imperialism despite the fact that they are often repositories of colonial wealth.

British museum-goers are hard pressed to find African collections on permanent display in the UK today. While it is unusual for any European museum to focus solely on African collections, this does not negate the existence of African objects within many museum collections, whether ethnographic, scientific or decorative in their nature. Contemporary absences in the interpretation and/or display of African objects only emphasise inequality within museum spaces. As Annie E Coombes explains in her book, Reinventing Africa: Museums, Material Culture, and Popular Imagination in Late Victorian and Edwardian England (1997), ‘ultimately, it is only from a more complex understanding and admission of the historical role that the cultural object has played in an imperial past that we can envisage the part it might now play in the realisation of a truly Post Colonial future’ (Coombes, 1997, p 225). These museums, created within a colonial context, have continued to impact their visitors well into the twenty-first century, a truth which is made evident through the types of visitors which museums usually attract, as well as their ability to reflect or comment upon society and popular culture.

The RMCA was long overdue a change to its colonial collections, interpretation and museum building. Many reviews of the original space make critical mention of the colonial exhibits. Rahier referred to the building as a ‘dusty colonialist exhibition’ (Rahier, 2003), while Hochschild lamented that the intentions of the Museum had not ‘changed in the slightest’ since its inception (Hochschild, 2012, p 292). To give an example which illustrates this problem, the original RMCA featured a statue commissioned by the ministry of the Colonies in 1913 to show a ‘Leopard man’ (Anioto), a figure which sprang from a popular rumour that murderous men dressed as Leopards were killing innocent people in the Congo.

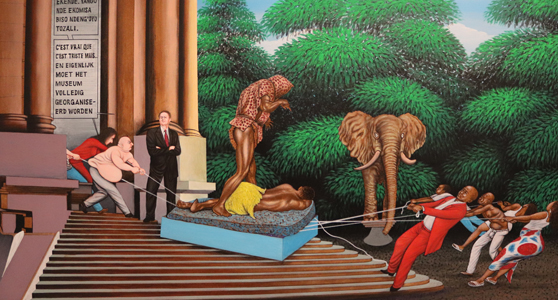

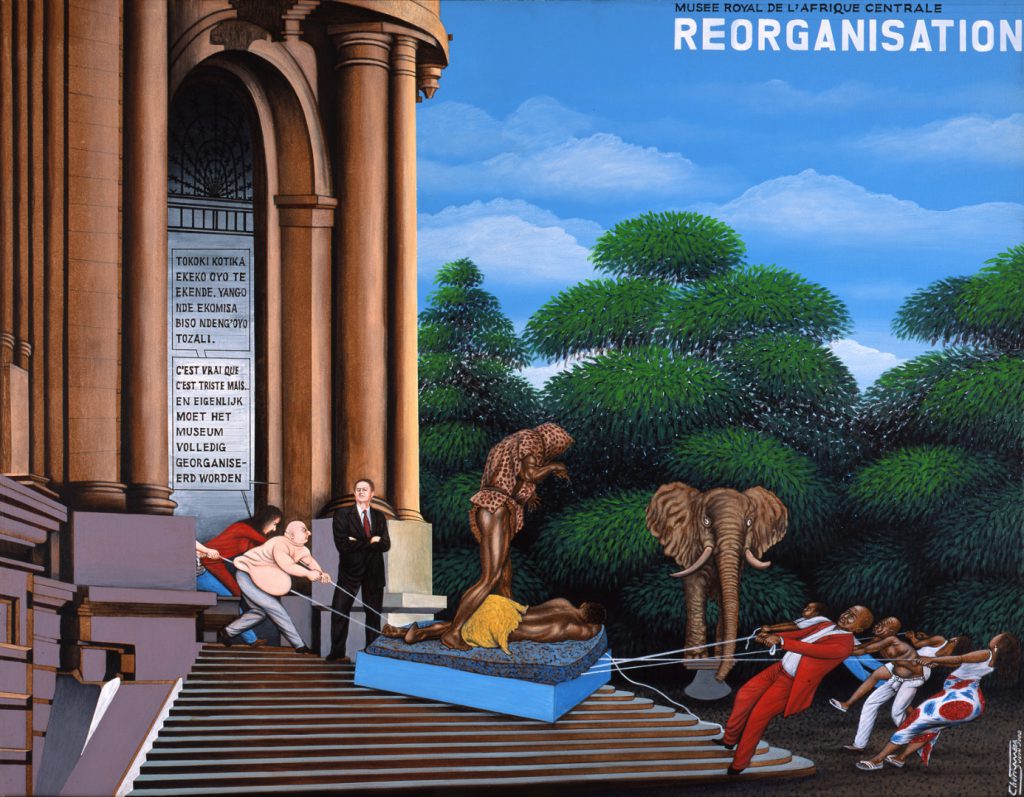

The image of the statue became widely spread within Belgian society, even featuring within the popular and heavily racialised Hergé comic, Tintin in the Congo, first published in 1946.[3] In the spirit of change, the Anioto is no longer a prominent feature of the RMCA’s new exhibition space and is instead featured in the room titled ‘Sidelined’ (a space which recontextualises a selection of colonial archive material and objects). The accompanying label now remarks that ‘Such leopard men existed, but only in the context of ritual warfare, and then only in a limited area’. New curatorial narratives are not guaranteed to change the visitor’s view of the Anioto; however, it is good that the Museum recognised former views and denounced these through the object’s label.[4] With the ninetieth anniversary of Tintin in 2019, the cover of the newly printed covers of Tintin in the Congo have been changed from a racist caricature to an encounter between Tintin and a lion. ‘Réorganisation’, a work in the new RMCA by artist Chéri Samba also references the Anioto statue. The piece shows RMCA staff and Central Africans fighting over whether to keep or remove the Anioto statue from the Museum.

As the RMCA has begun to demonstrate, museums should acknowledge their collections, and work to redress their vast colonial privileges. Whether focusing on physical gallery spaces, their centuries old reputation or access to research funds, an ‘ironic and self-critical eye’ is needed to begin the process of decolonisation (Coombes, 1997, p 221).

Visiting the new Museum

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191213/003One evident success of the new RMCA space is the inclusion of a multitude of languages in the displays. The very nature of modern Belgian multilingualism means that there are at least three languages – Dutch, French and English – on display at any time. This allows for wider access and an increased opportunity for the decolonial messages of the displays to impact audiences. This multilingual approach is further enhanced by the RMCA’s work with Central African communities. The galleries are brought to life with the opportunity to hear Central African languages throughout the displays. The mix of Central African and European languages spoken through films in the galleries serves as a reminder to visitors that the space is not limited to European understanding, enjoyment and interpretations of objects.

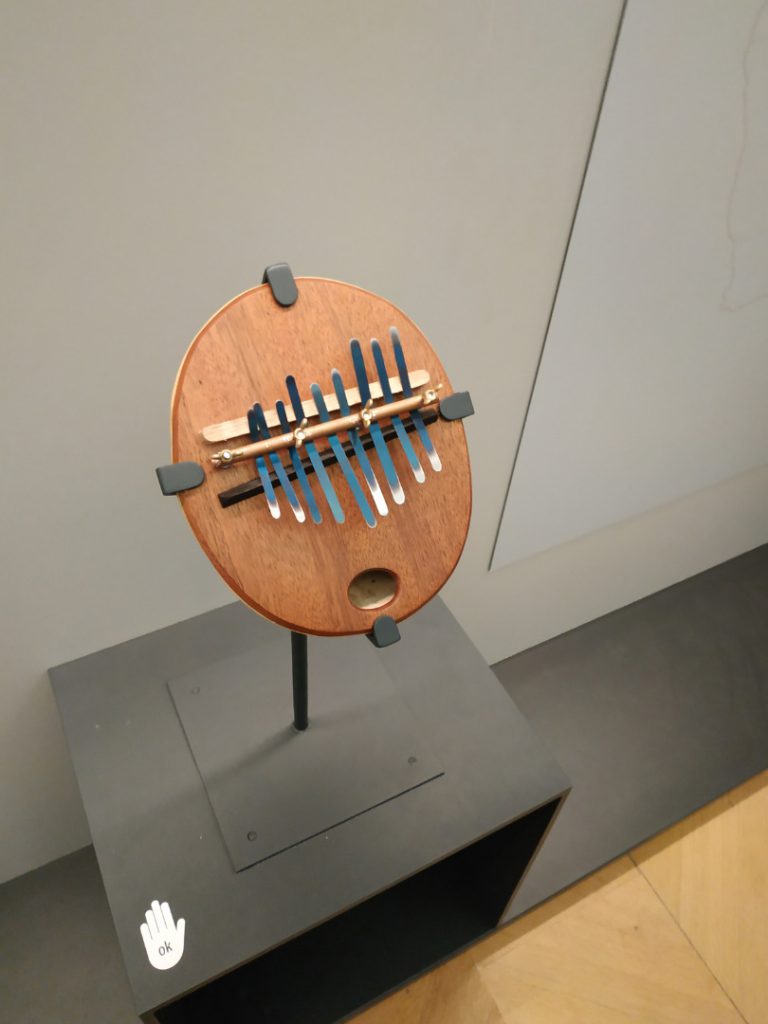

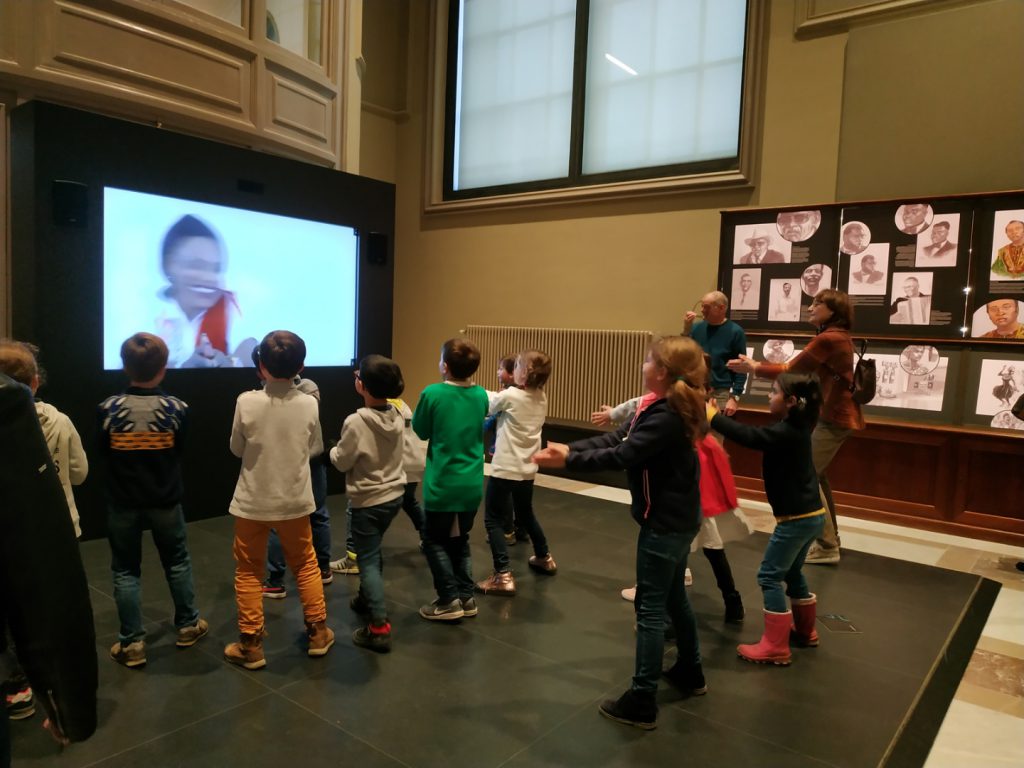

Though the majority of objects in the new Museum are in cases, touch objects within the gallery provide the opportunity for visitors to directly engage with objects. This is a method which is also employed more and more frequently in museums. UK examples including the Secret Life of the Home gallery (Science Museum) and the Sea Things gallery (National Maritime Museum). The new RMCA uses this interactive approach particularly effectively when focusing on its collections of musical instruments, providing, for example, a slit drum which can be played as it would in the set-up of an orchestra from the Congolese Pende community, or a dancefloor upon which to learn the dance moves to contemporary Congolese music (for example, rumba). At the time of my visit I was able to see a visitor playing a Kalimba, releasing a sound which enriched the sound environment of the African languages and music room. During my visit the adult visitors appeared to be too shy to directly follow the dance tutorials which were provided on a large screen in the studio rumba room. This changed, however, when a school group entered the room and over twenty children began to learn the basics of Congolese rumba.

Despite the joys of the Languages and Music gallery, not every area of the refurbished RMCA is successful in its efforts to decolonise. Though the content of the exhibition spaces has changed, it is important to note that colonialism is frequently woven into the very architecture of museum buildings. The grandeur of the buildings reflects colonial ideologies of wealth and superiority, creating spaces that memorialise the politics of the day. The Rotunda and Lieu de Memoire (site of memory) are two such places which directly attempt to tackle the problematic nature of colonised spaces. Both feature commissioned artwork from African artists in direct dialogue with the colonial buildings: Aimé Mpane’s work featuring in the Rotunda space, and Freddy Tsimba’s work featuring along the Lieu de Memoire.

The rotunda space felt entirely uncomfortable to me as a visitor. Though Mpane’s work, New Breath, or Burgeoning Congo, does have a presence in what is the former entrance to the Museum, statues of King Leopold and other colonial Belgians continue to tower just above visitors’ heads (as the statues are placed in raised alcoves), decadently painted in gold. At the time I visited, I seemed to be one of the only visitors who was dismayed by the dominance of the statues, with other visitors taking casual pictures with the nearby taxidermy elephant or simply marvelling at the colonial architecture of the room.

The Memorial gallery features Freddy Tsimba’s art commission. His work physically casts a shadow over the memorialised names of the 1,508 Belgians who died during the early colonial period (1876–1908) in the Congo. The shadow is in the form of the names of the seven Congolese people who died at the Brussels International Exposition of 1897 in Tervuren, and the seven names represent the many more who died under the hand of King Leopold’s colonialism.

Despite the power of the artwork in theory, it is a weather-dependent piece. When I visited the light conditions made the work invisible and in its absence the Memorial gallery appeared as a long hall dedicated to Belgian colonialists. Though contemporary commissions do help in the reinterpretation of the Museum’s colonial architecture, the power of the contemporary pieces are often swamped by the overall dominance of the gold and grand tributes to Belgian colonialism.

Contemporary material from Central African communities features in nearly every gallery of the Museum and felt somewhat more effective. With videos provided to explain everything from Central African linguistics and music, to fashion and cultural ceremonies, the contemporary videos provide multiple opinions and interpretations from the community of origin.[5] One such video, for example, explained the importance of the Kiswahilli Kanga, a cotton wrap for women which features proverbs and sayings. Women in the video explained the different jina (proverbs and sayings) which were also displayed through fabric on display in the gallery. Here the RMCA is careful not to generalise, providing a platform for a multiplicity of voices and mentioning that women ‘may wear their kanga to communicate or to voice personal or political opinions’ (Kanga: it’s a wrap, RMCA, 2018).

Another video looked at sign languages in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), with Congolese linguist John Mukabila giving an explanation of the languages used for those deaf and hard of hearing in Lubumbashi, DR Congo. His description of languages which are “creatively adapted to local realities, with signs for neighbourhoods, food and Congolese politicians” provides an insight into the realities of contemporary life in the Congo and gives a place for underrepresented African voices. However, while it was good to hear Central African voices in the space, I was put off by the hypervisibility of black people on screen versus the lack of black visitors/staff members in person. It made me wonder about the extent of change to the teams behind the scenes of the Museum, and whether central African people and voices will be truly welcomed and valued past the reopening of the permanent gallery spaces.

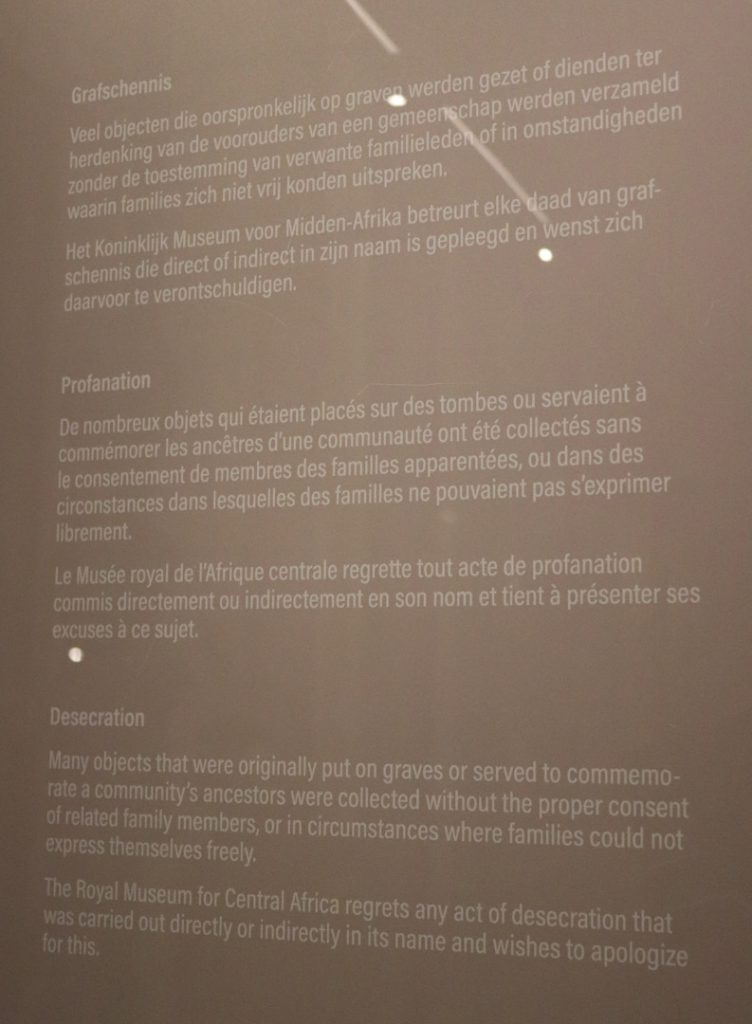

In fact I found myself questioning the advertised radicalness of the new RMCA spaces several times as I moved through the galleries. The text sometimes seems to seek neutrality, referring ever so softly to very violent events which took place in Belgian-Congolese history. The A0-sized desecration text panel in the Rituals and Ceremonies gallery is one such prevaricating panel. It reads:

Desecration. Many objects that were originally put on graves or served to commemorate a community’s ancestors were collected without proper consent of related family members, or in circumstances where families could not express themselves freely. The Royal Museum for Central Africa regrets any act of desecration that was carried out directly or indirectly in its name and wishes to apologize for this.

Though the label apologies for desecration, the objects are still shown as per original intentions – within the museum context – continuing the very act of colonial desecration the label condemns. The visitor is not informed about any research into this area and is instead presented with a rather empty apology. The colours of the text panel also look as if they were chosen to be ignored. White writing on a beige background does not shout “read me” in any context. The RMCA would have benefitted from discussing provenance in this space, along with repatriation and any efforts they have made to actually return the funeral objects.

Conclusion – ‘Everything passes, except the past’

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191213/004

Entering and exiting the Museum, visitors are confronted with a quote which reads ‘Everything passes, except the past’. This quote references a larger project by the Goethe-institut in Brussels, exploring colonial heritage in Belgium, France, Italy, Portugal and Spain (Goethe-institut , 2019). It provides both moments of exploration and closure for the visitor, as the Museum, despite the perceived successes or failures in the galleries, admits that history and colonial legacies still hold power within our society to this day. In an interview for the UK-based Museums Journal, the Africa Museum’s Director of Public-Oriented Services, Bruno Verbergt, mentions that we live within a paradox: “You cannot change the past, but one should be more open about what has happened and how past actions are now seen as morally wrong” (Adams, 2019a, p 35). It has taken much bravery from the RMCA to shut their doors until they come up with a new way of looking at the space and collections, and a large step has been taken in the right direction dealing with the Museum’s ultra-colonial content. Though there are good intentions behind these words and the general actions of the RMCA, more needs to be done to ensure that colonial legacies are made absolutely transparent. The past should be discussed, no matter how embarrassing or inhumane, in order to ensure that the power structures which built institutions all over Europe (and the rest of the world) become spaces of inclusion and representation. Though I am black, by the end of the travel through the museum space I felt like a voyeur. Perhaps because of the lack of black visitors and staff members that I came across – I found myself physically in a space which speaks about black stories but where those stories are not consumed by black people. But I also felt that to be truly decolonial there must be more efforts to become radical with the museum contents – museums must take sides calling out the injustice of a racist and imperialist past rather than merely trying to stay in a space of neutrality throughout the majority of exhibits. The UK is also no stranger to the issues described above, as museums frequently uphold a stayed hand and stiff upper lip when it comes to admitting the impact of British imperialism. Bold labelling and a willingness to make museums more transparent are also steps that British museums should take towards decolonisation. They must also create more research opportunities for those who would like to study objects and theories related to the colonial process and legacy. Outspokenness from the RMCA in relation to Belgian history would help to build the Museum’s brand and reputation, earning a level of trust from visitors that has otherwise been broken down by the events of the past and colonial inheritances which still present themselves in the present (Hope, 2019; Adams, 2019b). Though some good work has been done by the RMCA to break down colonial mechanisms, there is still room for improvement in their future decolonising methods.

Tags

Footnotes

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text