Wounded: ‘They had no fever…’ Ambroise Paré (1510–1590) and his method of gunshot wounds management

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191105

Abstract

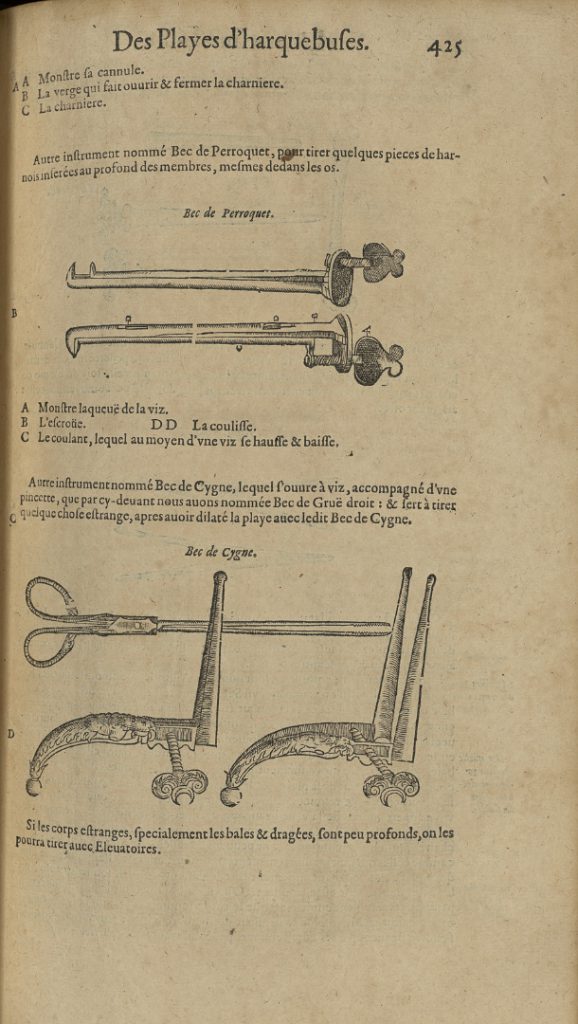

By the fifteenth century firearms had spread all over Europe, but surgeons had no idea how to cure gunshot wounds. It was generally accepted that high mortality from gunshot wounds could be explained by some kind of ‘gunshot poison’ entering the body with the bullet, but information and practical advice on managing gunshot wounds varied enormously across Europe. There were no appropriate instructions for such a new kind of wound in the ancient medical tradition and more recent ideas were unevenly distributed. Although known in Germany, Hieronymus Brunschwig’s Buch der Wund Artzney (1497) seems to have been unfamiliar in France and instead French surgeons focused on Giovanni da Vigo’s La Practique et chirurgie (1542), which was translated into several languages. Ambroise Paré also followed da Vigo, but in the battlefield he had to revise the generally accepted method of gunshot wound treatment. In response to his experiences he proposed a new version of wound care where cauterisation was replaced with a ligature of the vessels and the use of a healing balm dressing. In his treatise Des Playes faicts par haquebutes et autres bastons à feu (1545) he described the main stages of healing and the principles of wound care he finally adopted. As Paré fell out of fashion, the idea of ‘gunshot poison’ was rejected by the medical authorities, but the technique of cauterising gunshot wounds, abandoned by Paré, was still practiced.

Opponents of Paré argued that only a few people were cured by him and that those who were, were not seriously injured. It is of course impossible to know how many soldiers were cured with the help of Paré’s method but it nevertheless served as a basis for a new surgical paradigm. Perhaps most importantly, Paré’s method centred on the wish to reduce pain in the treatment process – an idea that was entirely new and ahead of its time.

Keywords

Ambroise Paré, cauterisation, Giovanni da Vigo, gunshot wounds, history of surgery, wound dressings

Early methods of treating gunshot wounds

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191105/002Medical practitioners in medieval Europe accumulated significant experience in treating wounds (Tracy and DeVries, 2015). However, all the accepted skills became ineffective in the face of a new challenge – the invention of the firearm.

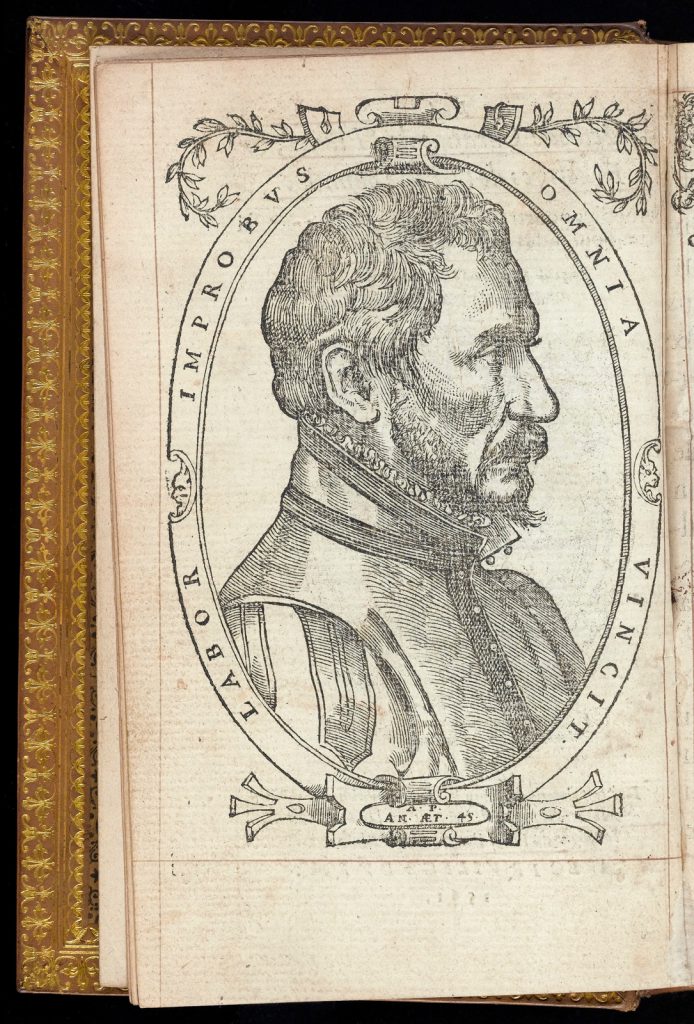

Today, the most revolutionary method of gunshot wounds management is mainly attributed to the French surgeon Ambroise Paré (1510–1590) (Dumaȋtre, 1986), royal surgeon to four kings of France (Henry II, Charles X, Henry III and Henry IV). Paré practiced as a battle-field surgeon in the last Italian wars (1542–1546 and 1551–1559) and in the Religious wars in France (1562–1598) so he experienced first-hand the urgent need to find a way to treat this entirely new type of wound. In this paper we will discuss the context in which his treatment was developed and we will analyse how his methods were received by Paré’s contemporaries and their place in the development of contemporary surgery.

Though the first use of firearms in Europe took place in the battle of Crécy in 1346, there were not many guns in existence at this time, and they were not used regularly in military conflict before the second half of the fifteenth century (Chase, 2003). Although the range of these early firearms was no more than 15 metres and firing accuracy left much to be desired, a bullet could still punch through metal armour and was more deadly than an arrow from a crossbow. An important feature of gunshot wounds was the kinetic impact of the hot bullet. In addition, lead bullets shattered when hitting a target (armour, clothes or a body) and the damage caused often spread wider than the diameter of the entry wound. Foreign bodies which got into the wound channel (mostly fragments of clothes) caused inflammation, suppuration, then sepsis and death.

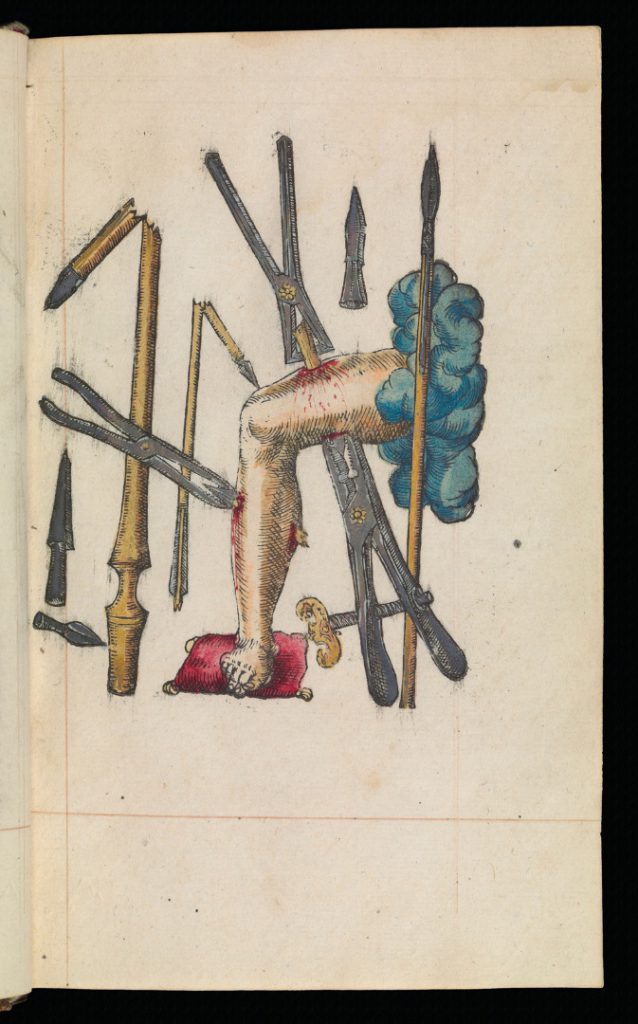

Kelly DeVries argues that medieval surgeons practiced two different ways of curing wounds. One was cauterisation with a hot iron, but the second method (recommended by Henri de Mondeville, a fourteenth-century French royal surgeon, among others) was to cleanse the wounds with balm or ointment (DeVries, 1990, pp 135–137). Both methods were widely used for treating patients and we do not know exactly how effective they were, but the advent of firearms created new tasks for military surgeons. Mortality from gunshot wounds was much greater than that inflicted by steel weapons; extraction of bullets and foreign bodies, such as chards of cannonballs, had a greater effect on the body than the extraction of an arrow. Nevertheless, only a few surgeons of this period conceptualised gunshot wounds as being of a different nature to the wounds made by cold steel.

As there was no ancient tradition to explain the mechanism of this kind of wounding, it became necessary to look for new explanations. In 1497, a German surgeon, Hieronymus Brunschwig (1450–1533), published The Book of treating gunshot wounds (Buch der Wund Artzney) (Brunschwig, 1497). He was probably the first to argue that gunshot wounds were poisoned. Saltpetre, an integral part of gunpowder, was already considered a poison, and Brunschwig also argued that the appearance of gunshot wounds was reminiscent of the wounds caused by poisoned arrows or the bites of mad dogs and poisonous animals. It was Brunschwig who suggested that such wounds be treated with cauterisation, following the practice of ancient physicians when treating poisoned injuries and continuing the belief that fire would halt the effects of poison (Sigerist, 1946; Shane Tubbs et al, 2011).

Brunschwig’s reasoning seems to be typical of the time: death that could not be explained by medical practitioners was often understood to be the result of poisoning (Collard, 2003). According to this theory, the common symptoms of gunshot wounds such as fever, physical debility, a blue hue to skin, vomiting and mental confusion, were all explained as the effects of ‘poison matter’ penetrating the body together with the bullet and gunshot powder.

Brunschwig’s treatise was written in German and was not translated into Latin or any other language. Thus, it was not familiar to French surgeons. It is worth noting that in the sixteenth century, Latin ceased to be the lingua franca of scientific communication, as vernacular languages were increasingly adapted (Olschki, 1927). In one sense this increasing vernacularisation of surgical texts increased the spread of knowledge since they could now be accessed by non-university educated medical practitioners (Siraisi, 2001, pp 37–49). In sixteenth-century France, for example, the members of the surgical community Saint-Côme published their textbooks in French, thereby raising the status of their profession in France. (Brockliss, Jones, 1997, p 104). However, this trend also limited the audience of a particular text to a linguistic region. Without access to Brunschwig, most European surgeons learned about the method of cauterisation of gunshot wounds through the writings of Giovanni da Vigo (1450/60–1525) whose book Practice and Surgery (La Practique et Cirurgie, 1542) became the medical bestseller of the sixteenth century. Da Vigo’s work was published in Latin, French, German, Italian and English for almost two centuries and was thus very widely available. The last edition appeared in 1713.

Da Vigo argued (p 224) that there are three distinctive features of a gunshot wound: 1) mechanical lesion (contusio); 2) the burn from the hot bullet and gunshot powder (combustio); and 3) intoxication of gunshot powder (intoxicatio). The two first points were adapted and accepted, but it was with the concept of intoxicatio (or poisoning) that European surgeons struggled with in the sixteenth century.

Da Vigo’s recommendations followed the ancient medical principles in many respects (Mounier-Kuhn, 2006, pp 155–156). But in emphasising three different impacts, he argued that the management of a gunshot wound is much more complicated than the treatment of a blade weapon wound. While acknowledging that ancient surgeons had no experience of such injuries, da Vigo nevertheless resorted to the authority of Galen who taught that if a person experienced two or more illnesses at the same time, the medical practitioner was to treat the most dangerous. Considering intoxicatio a fatal danger, da Vigo prescribed treatment with hot liquids, for instance boiling olive oil. This method was based on the ancient tradition of curing wounds made with poisoned arrows. According to modern surgical practice, the perceived effect of high temperature liquids on the gunshot wound can be explained by the coagulation of tissues, which da Vigo and his contemporaries understood as stopping the absorption of poison or rendering the poison inactive while healing.

Thus, da Vigo seems to have created the first theory-driven approach to curing gunshot wounds. He described the steps of gunshot wound management: the first one is cauterisation with boiling oil to stop the effects of gunpowder poison. The cauterisation provokes an iatrogenic burn, i.e. one caused by the treatment, which was understood to be less dangerous than poisoning. The next step was to treat the burn. For wound treatment after cauterisation, da Vigo recommended several remedies, for example a barley decoction with earthworms and a digestive potion[1] of turpentine, rose oil and egg yolk.

Ambroise Paré: ideas and practice

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191105/003Da Vigo’s method became the accepted surgical method all over Europe, and Ambroise Paré was among those who were taught to treat gunshot wounds in this manner. He was only 24 years old when he became a military surgeon, and had never seen a gunshot wound before, so he could only rely on surgical texts as a guide for how to treat them. Paré memorised de Vigo’s treatise by heart[2] However, the reality of treating patients with gunshot wounds proved to be different from the description in the books.

This is how Paré later described the circumstances of his discovery during the siege of Torino in 1536:

At that time I was a complete novice and I had never seen the treatment of wounds made by the harquebus[3]; but I had read in the first book of Jean de Vigo about wounds in general, chapter 8, that wounds made by firearms are poisoned because of the powder and that they are to be cauterized with oil of elderberry with a small quantity of theriac[4]. I knew that such treatment caused terrible pain for the wounded, so I wanted to know before I used it how the other surgeons carried out the first dressing; this they did by applying the nearly boiling oil as to the wounds so I plucked up courage to do likewise. At last the oil came to an end, and I had to use instead of it a digestive made of egg yolk, oil of roses and turpentine. That night I could not sleep thinking that the wounded who were not cauterized would die, and this made me get up at first light to visit them. Beyond my hopes I found those on whom I had put the digestive dressing feeling little pain from their wounds which were not swollen or inflamed, and having spent quite a restful night. But the others, to whom the said oil had been applied, I found fevered, with great pain and swelling around their wounds. From then I resolved never again so cruelly to burn poor men wounded with harquebus shot.

Thus, through the practical circumstances of war, Paré had a chance to compare the condition of wounded men in two different treatment groups and found that the cauterisation recommended by da Vigo was not as efficient as expected. The young surgeon failed in what he had been taught, but succeeded when he replaced the commonly used treatment with a new remedy.

We can infer that Paré’s method consisted of overlooking the first step of da Vigo’s treatment altogether. He began by treating the wound as if it was a burn, without cauterising it first. According to him, it hardly amounted to medical care at all – he simply could not leave the patients without help – but the results were staggering.

For years afterwards Paré made several attempts to explain the results of his involuntary experiment. In 1545 he published his first small book, The method of curing wounds caused by harquebus and firearms, which included a description of his discovery (Paré, 1545), and he continued to write on it afterwards.

His arguments against the cauterisations are as follows: gunpowder consists of a mixture of sulphur, charcoal and saltpetre. None of these elements separately are poisonous and so they can’t be poisonous as a mixture (Paré, 1585, p CCCCLIIII). Paré adds that during the Italian wars he saw German prisoners put a pinch of gunshot powder into their wine to make it stronger and were not poisoned as a result (Paré, 1585, p CCCCLV).

Although Paré argued that gunshot poison does not exist, he did note an important difference between bullet wounds and cold steel wounds stressing that the internal damage of bullets and cannonballs is much greater because of the force of the weapon. Paré often compared the ferocity of firearms with thunderstorms and he maintained a firm stance against firearms – perhaps because he had seen their effects himself – describing them as terrifying and ‘invented by devil’ (Paré, 1585, p CCCCXVI).

Another argument in favour of Paré’s new method was its ability to limit pain. Cauterisation was extremely painful, which neither da Vigo or Brunschwig remarked upon. Paré was probably the first to discuss the problem of pain during treatment and argued that it was not appropriate for Christians to burn a wound by fire before less extreme remedies were used (Paré, 1585, p M.CCXVII).

Contemporary reactions to Paré’s treatment methods

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191105/004The sixteenth-century medical and surgical communities were conservative, so Paré faced mixed reactions from his contemporaries: in fact, it could be argued that he had more opponents than supporters. One of his strongest critics was a doctor of medicine and member of the Paris medical faculty, Julien Le Paulmier (1520–1588), the author of Book on nature and treatment of gunshot wounds (Le Paulmier, 1569). Like Paré, Le Paulmier rejected the idea that there could be gunshot poison inside the wounds and categorically rejected the practice of cauterisation. He employed traditional Galenic arguments to back up his ideas: these suggested that since gunshot wounds are of a hot nature, the cauterisation with boiling oil or hot iron is unacceptable. Because of this theoretical position Le Paulmier objected to the formulas of digestive liniments used by Paré. Le Paulmier argued that in the battles of Dreux and Saint-Denis during the Religious Wars, where Paré practiced as a military surgeon, only a few wounded soldiers survived among those who were treated by him with this method and most of those who did survive were not seriously injured (Le Paulmier, 1569, pp 2–3). Instead of Paré’s liniments, Le Paulmier proposed other treatments which would cool the wounds, ranging from cold water and melted snow, to complicated balms which were designed to alleviate the heat from the bullet (Le Paulmier, 1569, p 109).

Conclusion

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191105/005To conclude, in the texts of Paré, da Vigo and Le Paulmier, we see the appearance of several surgical techniques. One might imagine that all of these became outdated and are now known only by medical historians, and yet some are still in use today. For example, during the Second World War, cauterisation was used to treat gunshot wounds in the German army – it is mentioned in the memoirs of Hans Killian (Killian, 1966) who was a military surgeon of the Wehrmacht on the Eastern Front. Of course, German surgeons used this method in the absence of other medicines in the extreme environment of battle, and the procedure often caused gangrene and mortification of tissues. Surgeons to this day practice cauterisation of vessels to stop bleeding. Nevertheless the introduction of firearms into European warfare changed medical practice and some aspects of the remedies developed by Paré and his contemporaries to treat gunshot wounds also remain in use to this day.

Paré’s gunshot wound treatment was developed through rejection of earlier established theory and through direct experimentation. Many modern scholars describe it as an example of a victory of modern science against scholasticism (Porter, 1998, pp 188–189; Grmek, 1996, p 238). However, we must acknowledge that we do not know the exact details of Paré’s experiment: how many patients did he treat and how badly were they hurt, for example? Moreover, his personal success story did not change common practices, as da Vigo’s book remained in demand up to the eighteenth century.

In reality none of these surgeons knew exactly what was going on inside the wound after dressing. Paré clearly understood that the power of a surgeon is restricted by the forces of nature; as expressed in his famous words ‘I dressed him and God cured him’. What is central to his practice is his desire not to cause pain to the patient, something which is absolutely innovative in the sixteenth century as the era of painless surgery began much later.

Tags

Footnotes

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text