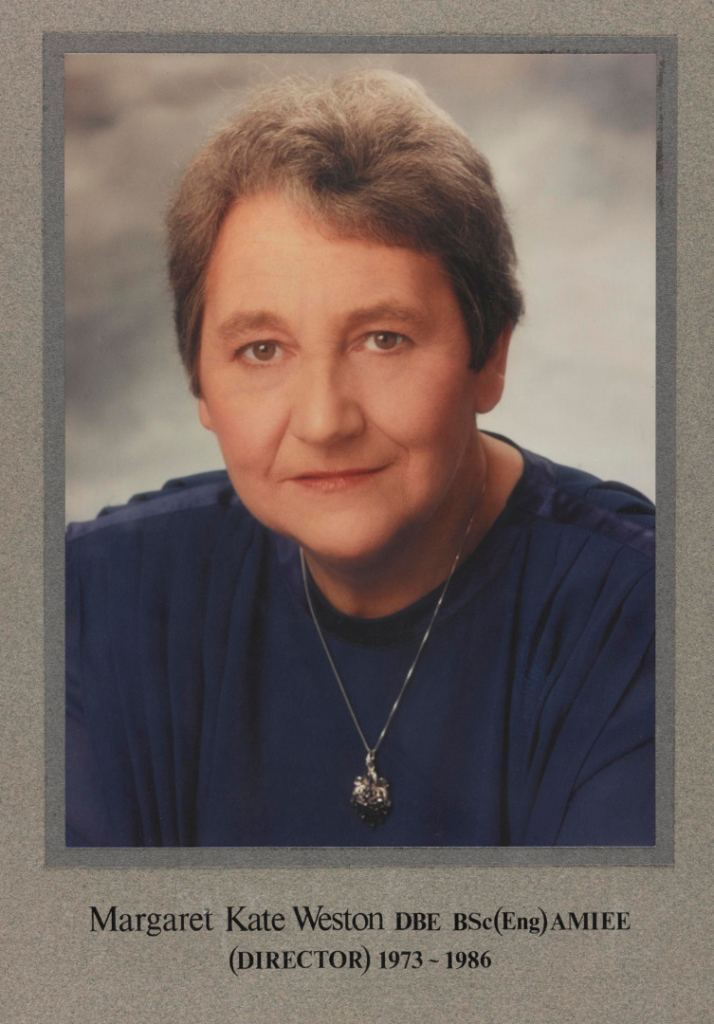

Obituary: Dame Margaret Weston, DBE, FMA (7 March 1926–12 January 2021)

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/211511

Keywords

Dame Margaret Weston, director, National Science and Media Museum, obituary, Science Museum

Today, when a significant number of Britain’s national museums and galleries have female directors – including the Tate, the National Museums of Liverpool, London and Northern Ireland, the Imperial War Museum, the Royal Air Force Museum, Manchester Museum and both the Sheffield and Birmingham Museums Trusts – we are at last beginning to take it for granted that such appointments can be made. But when Margaret Weston became Director of the Science Museum in 1973, she was the first woman to be given such a post. She was a pioneer – nearly half a century ago.

Margaret Kate Weston – to give her her full name – was born in Oakridge, on the outskirts of Stroud, Gloucestershire, on 7 March 1926. Both her parents, Margaret (née Bright) and Charles, were head teachers and she attended Stroud High School, where she became Deputy Head Girl. In the summer of 1940, a German bomber crashed near the school, and Margaret, then aged 14, apparently detained one of the crew until her father, who was in the Home Guard, came and arrested him. Unusually for a woman at the time, she went on to study engineering at Birmingham Municipal Technical School (now Aston University), qualifying as a chartered engineer at the age of 28.

Weston then became an apprentice at the General Electric Company in Witton, Birmingham, specialising in high-voltage insulation. In 1955, she left GEC to take up the post of Assistant Keeper in the Science Museum’s Department of Electrical Engineering and Communications. Here she was charged with developing a new electrical engineering gallery, which opened in 1957. She spent the rest of her 31-year career at the Museum, which was until 1984 a ‘departmental museum’, a designation given to both the Science Museum and the Victoria & Albert Museum since their creation after the Great Exhibition of 1851 and which meant that all staff were officially civil servants.

Five years after her arrival, Weston was promoted to the post of Deputy to the Keeper of the Department of Electrical Engineering and Communications, Gerald Garrett. Five years later still, she became the first Keeper of a new department, Museum Services, which united non-curatorial functions in a single department.[1] She made such a success of this that the Director at the time, Sir David Follett, came to rely on her and made her totally responsible for the public face of the Museum. When Follett retired in 1973, she became his successor.

One of the responsibilities Weston inherited from her predecessor was a plan to take over the rich historical collections of British Rail, stored at the time in Swindon, Clapham and York. In September 1975, two years after she became Director, the National Railway Museum in York was opened by the Duke of Edinburgh. It was the first national museum to be sited outside London and today, many years later, Dame Margaret is commemorated there by having her name on a miniature steam train, which visitors can ride on.

The National Railway Museum was only the first of the new outstations opened during Weston’s Directorship. The next was the National Museum of Photography, Film & Television, as it was originally called. Two name changes later, it is now the National Science and Media Museum. As Keeper of Film & Photography at the National Portrait Gallery throughout most of the 1970s, I had been campaigning for such a museum for several years. Weston was so supportive of the idea that she established a committee to progress it. I was the only member of that committee who was not on the Science Museum staff.

The big step forward came in 1979, when the Museums Association – of which Weston was at the time President – held its annual conference in Bradford, Yorkshire. While being driven through the city centre on a double-decker bus, Weston saw the empty Prince’s Theatre in front of the Wardley Tower, built in 1966. Over a civic dinner that evening, she asked the city’s Chief Executive, Gordon Moore, whether he thought the building suitable for a national museum of photography (I am not sure if film and television – her brilliant additions to the original concept – were in her mind at that point). When he said ‘yes’, she asked what the city would contribute. Moore suggested a free building and a considerable sum of money: in the end it cost £1.8 million to get the Museum up and running. If I can justly claim to have been the father of the National Museum of Photography, Film & Television, Dame Margaret and Gordon Moore were its godparents. Without them, it would never have happened, and it would never have become Britain’s sixth most highly attended museum, the most popular outside London and ‘the world’s most popular institution devoted to photography’ (New York Herald Tribune, 1989). It won the Museum of the Year Award in 1988.

When I was appointed to set up and run the Museum, I was given just seventeen months to get it open. Open it did – on 19 July 1983 – and a Times article marking the event said: ‘The idea of the museum was only conceived in 1979, and the speed with which it has been made a reality is a remarkable tribute to Dame Margaret Weston, who was then President of the Museums Association…and particularly to the museum’s philosopher and keeper, Colin Ford, whose combination of doggedness and dynamism had previously been largely responsible for the effectiveness of the National Portrait Gallery’s Film & Photography Department.’

Staff at the Science Museum in South Kensington were less supportive of the Bradford development than they had been of York. A national photography museum, unlike a national railway one, had not been a long-term target, and no extra government funding had been made available for it. This meant that staffing levels in London had to be reduced and, given Dame Margaret’s emphasis on education and public relations, this particularly hit curators.

Another problem was the matter of storage. Blythe House, a late Victorian building in Olympia, had been built as the headquarters of the Post Office Savings Bank. After this use came to an end, the government bought it for £6.5 million and offered it to the British, Science and Victoria & Albert Museums as a storage venue. This building was so grand that it had featured as the setting for many television programmes and films (notably the hugely successful Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy). The Director of the V&A, Sir Roy Strong, thought it too good to be just a store, and lobbied for it to be used for the public display of several of his museum’s collections: ‘Surely Blythe Road – which is a marvellous building – should be not just a dumping ground but an exciting new complex for the public.’ But it did become a museum store, and stayed so until relatively recently; the Science Museum’s reserve collections are now being sent 90 miles away from London, to the old Royal Air Force Base at Wroughton in Wiltshire where modern storage facilities are being built.

Dame Margaret had acquired the Wroughton site for the Museum in 1976, possibly at least partly motivated by the fact that, some years earlier, she had received a phone call out of the blue asking if the Science Museum would like to acquire Concorde 002, the supersonic British/French aeroplane which first flew in 1969. Her response was: ‘Well, I want to preserve it, but I have no place to put it.’ Typically, she added: ‘But yes, I’ll take it.’ In 1976, Concorde 002 made its last flight – to the Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm Museum in Yeovilton.

More successful was the acquisition on long-term loan of the huge collection on the history of medicine built up by Sir Henry Wellcome. Under Dame Margaret’s direction, a series of galleries were built to house this, and opened in 1980/81. Forty years on, the Wellcome section of the Science Museum is still thriving, re-housed on the first floor of the main museum, and displaying 3,000 objects – the largest of its kind in the world.

Dame Margaret’s other long-lasting addition to the London Science Museum was Launch Pad, an interactive gallery for children which opened in 1986, the year of her retirement. It is still going very strong today, having moved around several locations, now re-named Wonderlab and continuing to expand.

As her career progressed, Dame Margaret was beginning to be appointed to various public bodies. On 3 November 1975, she became a member of the Design Council and on 2 April 1977 of the Ancient Monuments Board.

A major change in the management of the Science Museum and its outposts occurred in 1984 when they were devolved from direct Civil Service control to administration by a Board of Trustees. The phrase ‘National Museum of Science and Industry’, which had been the Science Museum’s subtitle since the 1920s, was now used as a corporate title to describe the entire organisation. Weston’s concerns about working in this different environment were soon left behind and she continued to put the interests of visitors higher and higher on the agenda.

In the following year, Dame Margaret was elected an Honorary Doctor of Science at Leeds University and Honorary Graduate of the Open University. She also received honorary degrees from Aston, Bradford, Loughborough, Manchester, Salford and the Open universities.

When Dame Margaret retired in 1986, the staff gave her a motorcycle as a farewell gift. Her retirement was of course covered in the press and on radio and television; two of the most memorable celebrations were the publication in The Times of a photograph of her driving a 1911 Rolls Royce in the 1981 London to Brighton Veteran Car Run and her interview on the BBC’s ‘Woman’s Hour’.

After her retirement, Dame Margaret remained unstoppable. She became an Honorary Fellow of Newnham College, Cambridge, a Senior Fellow of the Royal College of Art, President of the Heritage Railway Association and a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts. In later years, this busy retiree became a founding Trustee of the Brooklands Museum and a member of the Museums & Galleries Commission. In 1989, she joined the Board of Management for the Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851, which continues to encourage research and education in science and the arts. In 1990, she was appointed chair of the Horniman Public Museum and Public Park Trust, which may well not have survived without her Herculean efforts. Further appointments are listed in Who’s Who[2], and research by this author and others suggests that even this list is incomplete. It is all certainly extremely impressive.

When Dame Margaret died this January, the BBC marked her death and celebrated her remarkable career in a section of its regular Radio 4 programme ‘Last Words’. A major contributor was Heather Mayfield, who worked at the Science Museum from 1979 to 2014, for her last four years as Deputy Director. Central to what Heather had to say about someone who had obviously impressed her enormously was that Weston was always full of energy, and ‘never took no for an answer’. Heather and I agreed that, however diminutive and grey-haired Weston was, she somehow always had a commanding presence, and was an extraordinarily accomplished negotiator. Heather also told me that she had informed the presenter of ‘Last Words’ that Dame Margaret said that her favourite out-of-London development was the National Museum of Photography, Film & Television. That statement was not included in the broadcast programme, but it was hugely gratifying for me to hear. Now, I only wish I had told her that she was the best boss I ever had – which she unequivocally was.