Revealing observatory networks through object stories: Introduction

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/232003

Abstract

This paper introduces a group of three articles that bring together object stories relating to observatory history and networks. The three articles (‘Instrumental networks’, ‘Object itineraries’ and ‘Observatory audiences’) each bring together three object stories by different authors that contribute to the article theme. Here the genesis of the collection at the workshops of the Observatory Sites and Networks project is discussed, along with the approaches taken and the kind of insights that studies of material culture can shed on histories of observatories and the observatory sciences. The arrangement of the stories into three themes is outlined while common threads and recurring motifs that create connections and synergies across the thematic sections are highlighted. Together the collected papers make an argument for the use of objects in research, demonstrating the fruitfulness of investigating their histories and showing how they can expand our understanding of the networks of people, organisations and objects that were interested in or essential to the successful functioning of observatories. They also demonstrate the breadth and variety of interests and resources that were drawn into these networks, offering new ways of understanding and interpreting both observatory sites and museum objects.

Keywords

astronomy, collections, networks, object biography, object itineraries, object stories, observatories, observatory sciences, observatory sites, scientific instruments, Time

The articles in this collection (‘Instrumental networks’, ‘Object itineraries’ and ‘Observatory audiences’) each consist of three object-focused stories that were inspired by the 2021–22 workshops of an AHRC Network Grant focused on Observatory Sites and Networks Since 1780.[1] Louise Devoy, Senior Curator of the Royal Observatory Greenwich (ROG), was the Principal Investigator, I took on the role of Co-Investigator and our project partners were Cambridge University Library (holder of the archives for the ROG), the Royal Observatory, Edinburgh, and Armagh Observatory and Planetarium. The grant funded a series of four workshops, which successfully brought together historians of science and astronomy, historical geographers, scholars of visual culture, curators, archivists, librarians, astronomers, science communicators and more to explore the histories, preservation and interpretation of observatory sites and heritage.

The network was put together with the forthcoming 350th anniversary of the ROG (2025) in our sights. Our focus was, thus, particularly on state-funded institutions, but we were keen to include studies of observatories from across the globe, in their different local, national, colonial and transnational contexts. Our contention was that observatory histories have tended to be institutional or national, and many are technical rather than social or cultural.[2] Taking inspiration from scholarship on the ’observatory sciences’, which includes but goes well beyond histories of observatory sites, we aimed to broaden the scope of observatory histories by emphasising the networks that surround and connect these sites.[3] These included personal and institutional networks that supported, or were formed by, the introduction or maintenance of instruments and practices; those that were created by individuals as they lived and worked on observatory sites, or as they moved between sites; and those developed between observatories, other institutions, government bodies and civic society. We also aimed to cover a broad period, comprising significant change, and to reflect the range of fields of research supported by permanent observatories.

Because of the Covid-19 pandemic, the first of the Network’s workshops was held online, in December 2021, which gave us an unexpected opportunity for increased international reach and contributions. These connections were sustained in the subsequent workshops by continuing to facilitate online participation. However, the in-person attendees of the three hybrid workshops, in March, June and September 2022, were able to benefit from visits to historic sites, libraries, archives and object displays and stores. They were held at (or close to) observatory sites in Greenwich, Edinburgh and Armagh.[4]

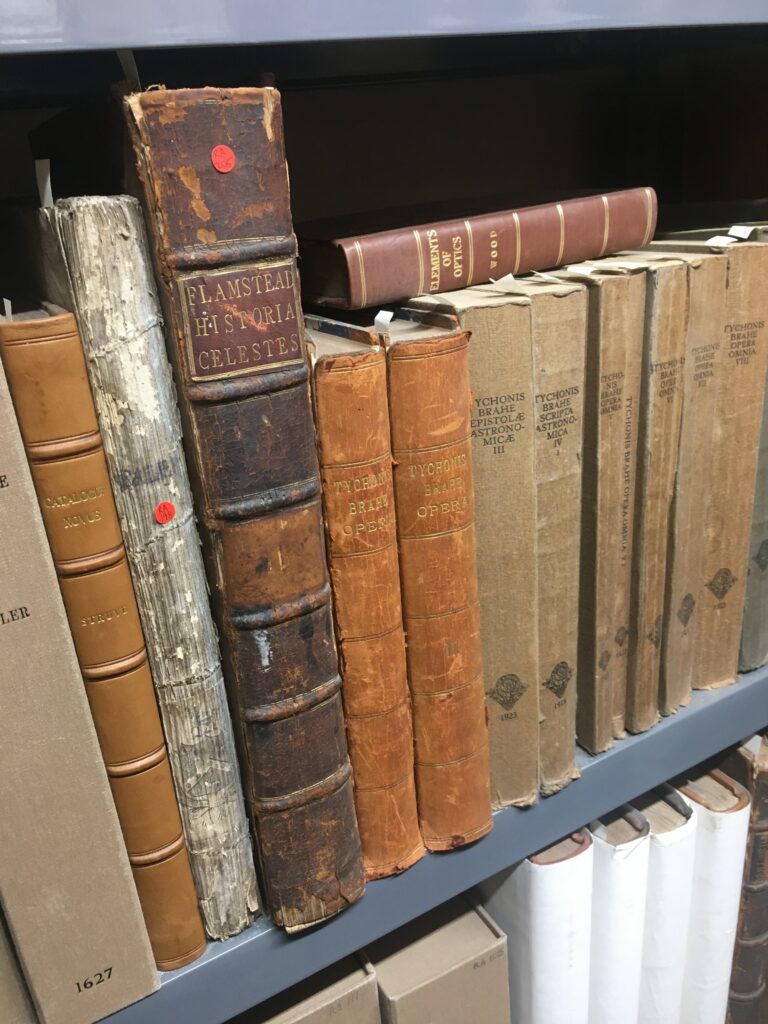

The showcasing of object, library and archive collections was one of our priorities. It was repeatedly made clear throughout the series of workshops that they are not only central to the research being done in the field but are also one of the defining features of permanent observatories. Always partly and, inevitably, ever-more historic in nature, such collections have been preserved cheek by jowl with and in support of the practice and promotion of the observatory sciences. While in working sites, these collections may be considered obsolete or as relics, and often await reassessment as historic objects. Others are acknowledged as tangible heritage, as observatory sites have transformed, fully or in part, into museums or when collections have been transferred to other institutions.[5] Gaining the status that comes with entering a heritage, archive or museum collection generates new kinds of attention and value but may risk losing connections to the original site and its assemblage of objects and materials. Our hope was that opportunities to hear about, view and share collections would draw attention to the preservation of such collections and generate future research directions and collaborations. This is beginning to pay off, including through the production of this set of stories.

Because it was purely online, the first workshop could not include site visits. However, we nevertheless ran a session that focused on objects in and from observatory collections. Louise Devoy, Ileana Chinnici and Pedro Raposo chose objects with contrasting tales to tell, creating a productive session that helped to develop our themes and inspire this collection.[6] Three other contributors (Susana Biro, Samantha M Thompson and Kelley Wilder) gave papers at the first workshop, which explored networks that supported the introduction of new instruments and imaging techniques. These were thematically related to but different from the object-focused studies they offer here. Emily Akkermans treated the attendees of the Greenwich workshop to some highlights of the horological collections in store, including the object she writes about at greater length here. Discussions among the authors, during and after the workshops, added two further object stories, one by me and one by Fernando Figueiredo.

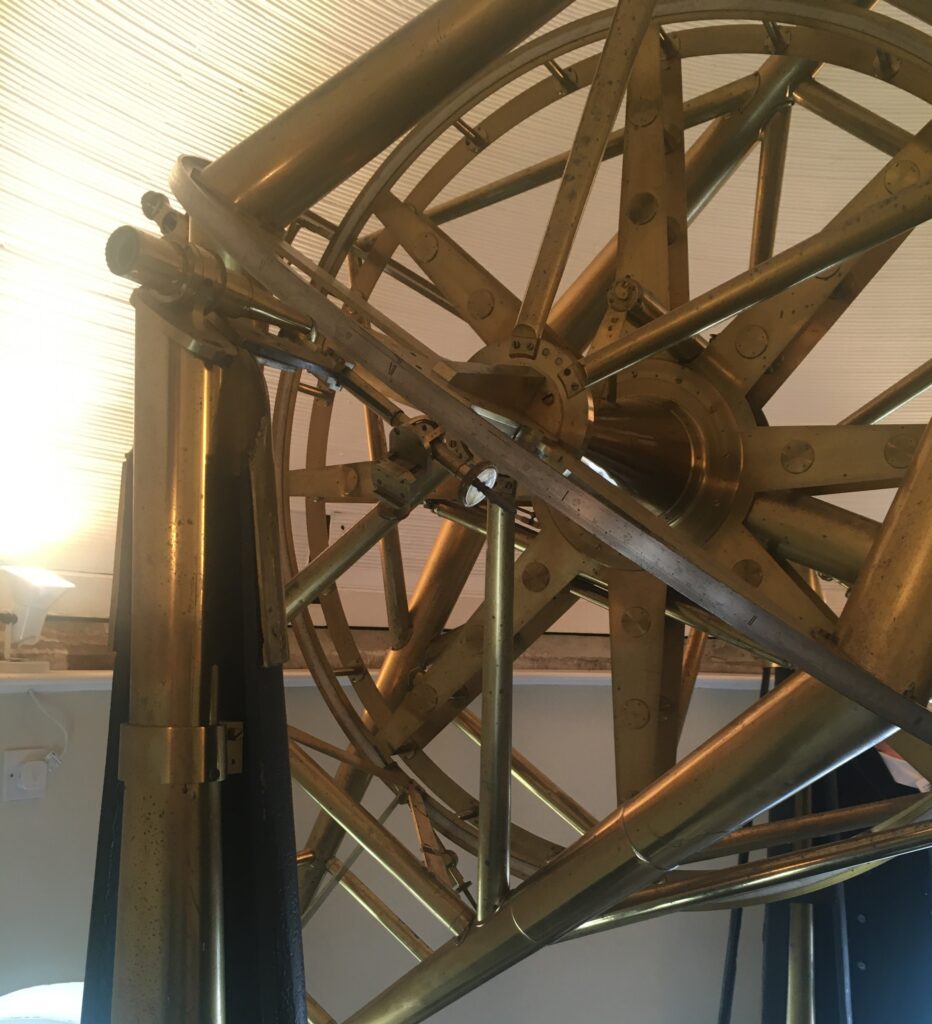

Each piece within this collection tells a distinctive story, though they share common themes that speak to the essentially networked and communicative nature of the observatory sciences. While the UK-based nature of the Network means that there are four British stories, there are also histories from the Americas and Continental Europe, ranging from the early nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century. There are stories about a telescope, a chronometer, electronic relays for time signals and starlight, a model time ball and time gun, a seismograph, photographic plates, an electronic imaging tube, and a table. Some of these objects are celebrated, at least in specific institutional or disciplinary contexts, while others have been nearly forgotten; neglected and obscure survivors. A number, by accident or design, displayed observatory work to audiences beyond its walls, but many are typical, even quotidian, parts of observatory equipment. All have required historians’ and curators’ skills to reveal or recover their significance to our understanding of observatory sites.

The object stories presented here are intended to be short and focused, and so do not offer comparisons with other observatory sites, though such work would be desirable in the future. Astronomy relies on connections and comparisons: the first task at an observatory is to establish its time and position in relation to other observatories. From the eighteenth century (Bennett, 1992), there was by design much similarity in the equipment and systems installed within observatories, first across Europe, then North America, European colonies and increasingly other parts of the world (Aubin et al, 2010; and see e.g. Razaullau Ansari, 2011, for the example of India). The networks that supported such efforts had to be joined or replicated, and some instruments, as similar as possible to those used elsewhere, acted as the key that gave access to important international networks, notably the seismograph and astrographic considered here (Figueiredo, in ‘Object itineraries’; Biro in ‘Observatory audiences’). Nevertheless, we contend that specific local contexts – institutional, technical, geographic, political, economic and social – mean that these were always uniquely configured.

For the purposes of this journal issue, the individually authored stories have been grouped into papers with the following three themes: ‘Instrumental networks‘ (Akkermans, Wilder and Thompson), ‘Object itineraries‘ ( Chinnici, Devoy and Figueiredo), and ‘Observatory audiences‘ (Higgitt, Biro and Raposo). ‘Instrumental networks’ highlights the networks – material and human – required for individual objects or object types to function as part of larger systems of information dissemination and knowledge production. ‘Object iteneraries’ emphasises the travels and changing uses or identities of the chosen objects over time, tracking their stories from commission to today, highlighting along the way the wide range of activities that can be associated with observatories. Each object in ‘Observatory audiences’ draws attention to the wider networks that observatories rely on for support and funding, from central government to local institutions or the wider public, and the role of others, including artisans, public lecturers and artists, in facilitating these connections.

The term ‘object itineraries’ has been chosen as a paper title over the perhaps more commonly used ‘object biography’. This recognises that biomorphic framing may be inappropriate to understanding the trajectories of objects through time and space and the impacts of these changes (Fontijn, 2013). In this paper, Chinnici focuses on a well-travelled chronometer, Whiffin 342, purchased by the Palermo Astronomical Observatory on the advice of the British Astronomer Royal, and used, not for maritime navigation, but to support terrestrial expeditions and the local time service. Devoy tracks the history of a table used in the ROG’s Octagon Room, revealing the staff and visitors who encountered it and, thus, the many activities beyond observation that take place in and are essential to the successful functioning of observatories. The story that Figueiredo tells of a Milne seismograph,from its commission by the University of Coimbra’s Meteorological and Magnetic Observatory to the newfound utility of its rolls of data today, shows how it placed the observatory and its staff within an international seismological network. Each of these itineraries also highlights moments of transition, from working object to obsolescence, and from obscurity to museum object or subject of new research.

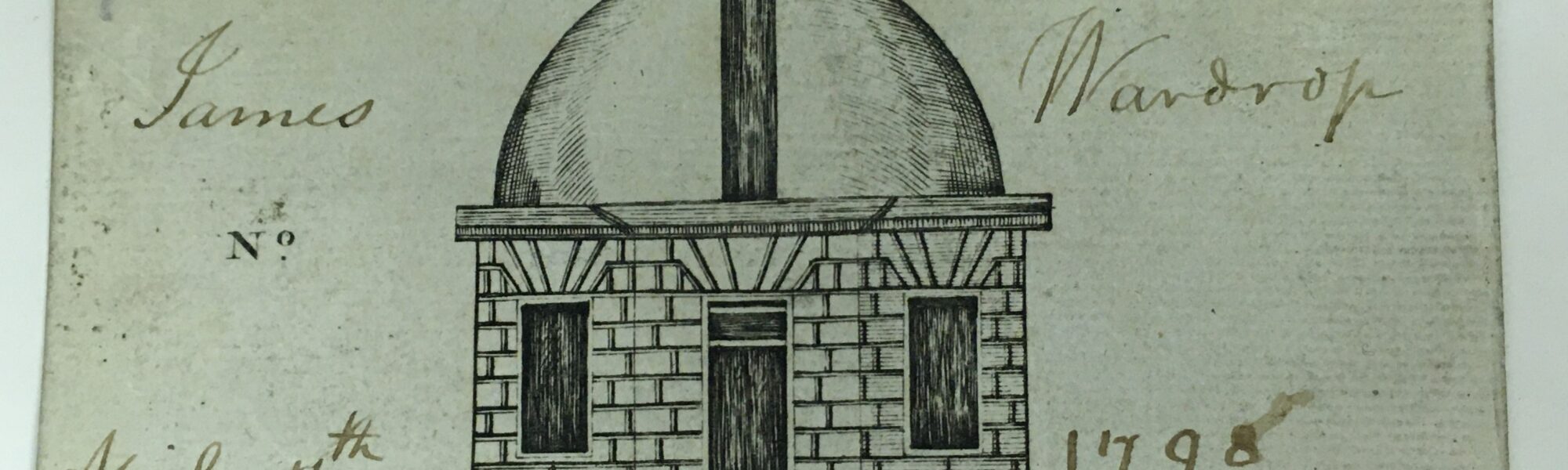

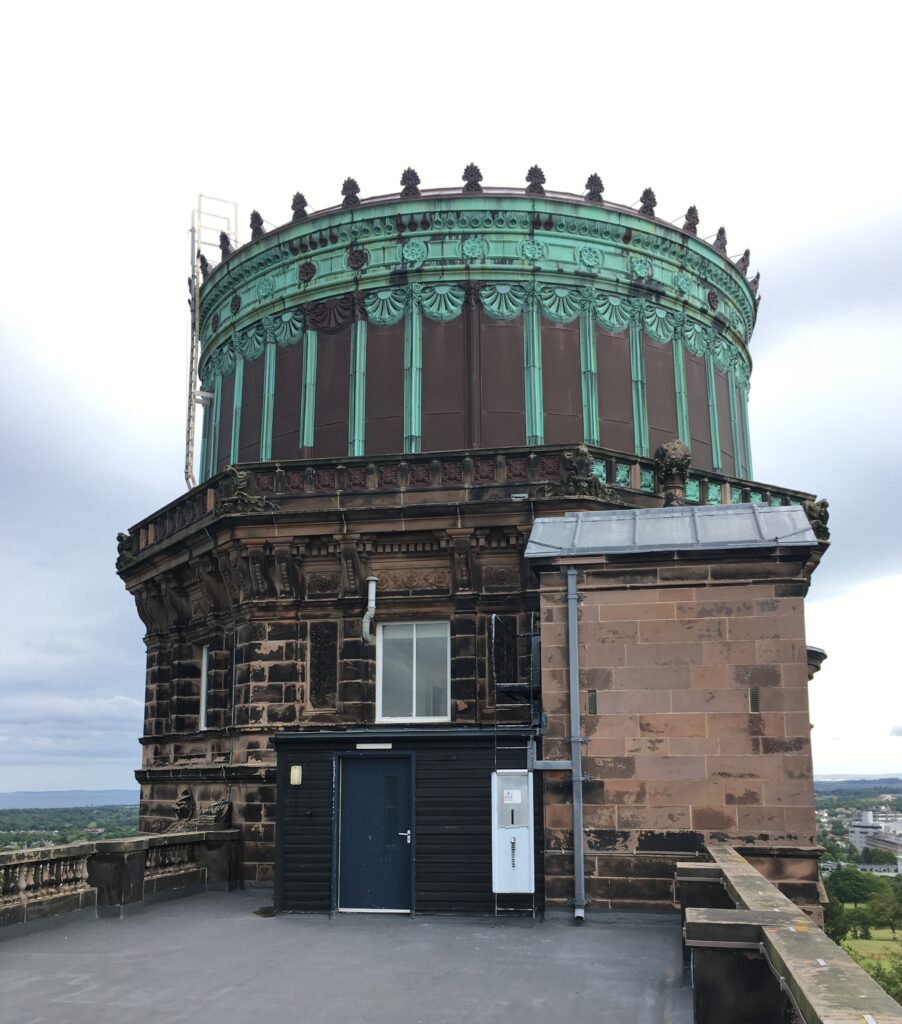

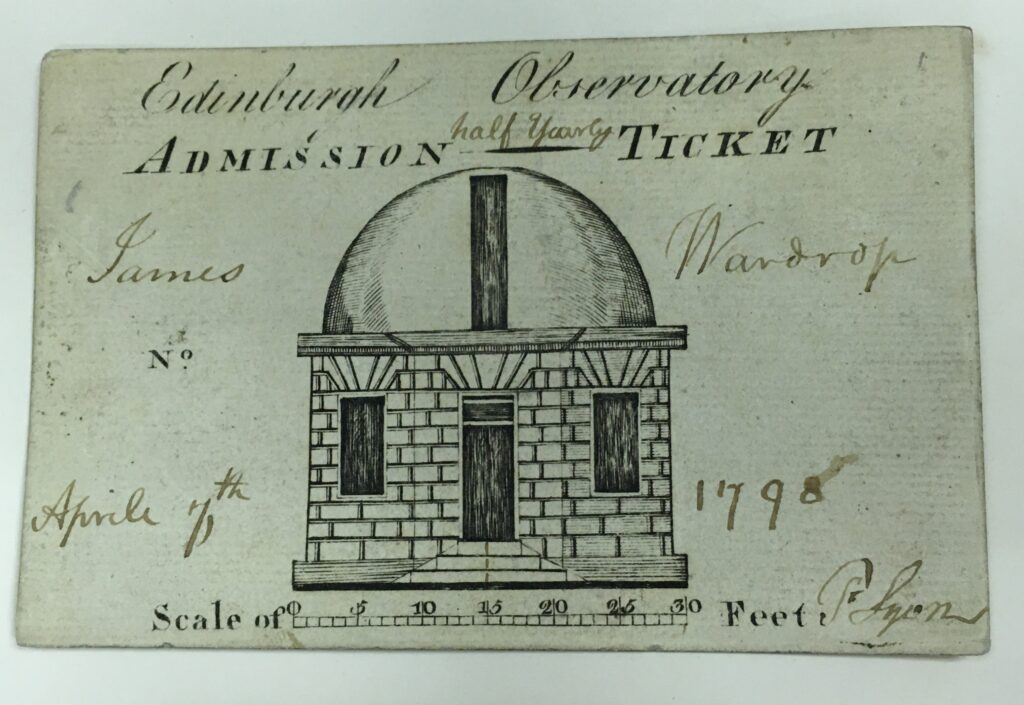

In taking an object-centred approach, several of the studies in other papers have also explored object itineraries, or parts of them, showing the usefulness of this approach in uncovering new connections, contexts and stories (Kopytoff, 1986; Alberti, 2005). Biro’s account of the astrographic telescope at the National Astronomical Observatory in Mexico in ‘Observatory audiences’ highlights its role in satisfying or inspiring different audiences for observatory-related activities, but does so by tracking the instrument’s itinerary from its commission, through its use in a series of different projects, and to its current role in heritage, art and science communication. In the same paper my own account of a model time ball and gun highlights local audiences interested in the Royal Observatory, Edinburgh, and its time service by tracking as much of the object’s itinerary as I have been able to uncover. As has been argued elsewhere, and is demonstrated here, objects ‘are constituted by and create social relations and networks, firstly at their points and places of origin and then through the various transformations of context, meaning and practice that travel across time and space’ (Byrne et al, 2011, p 21).

While the physical nature of the object – its function, materials, appearance, fragility, uniqueness or replicability, etc – necessarily informs all the stories, in some cases it has driven the argument.[7] Akkermans (in ‘Instrumental networks’) pays close attention to the physical network of instruments and wires that the ROG’s Hourly Signal Relay functioned within; a complex system, involving many more parts and considerably more labour than has previously been appreciated, and which only partially survives. Wilder’s scrutiny of photographic glass plates (‘Instrumental networks’), recording images captured at temporary observatories during the 1874 transit of Venus expeditions, requires her to consider the techniques, chemicals and training involved in their production, and their poor survival rate. Thompson’s focus on an electronic imaging tube, Lallemand‘s camera (also in ‘Instrumental networks’), reveals the need for, and often the lack of, a viable network of builders to support the potential network of users. The difficulty of use and fragile nature of this tube accounts for its poor take up in many locations and lack of representation in collections until now. Raposo’s account of a photoelectric relay, used to transform starlight captured at Yerkes Observatory into an electric impulse that would appear to light the 1933 Chicago Century of Progress Exposition (In ‘Observatory audiences’), brings this ‘black box’ to life through its role in the physical and personal networks that created a performative moment designed to impress audiences.

All the object stories make clear that many individuals, groups, skill sets, institutional contacts and knowledge holders, as well as funders and supporters, were required to undertake work that needed significant capital, infrastructure and shared resources. Several underscore the necessity of and the desire for international collaboration, for one or more of a number of reasons: astronomical and geophysical sciences often rely on observations from different locations, requiring overseas expeditions or international observing networks; there was a need to learn from and agree standards with other countries; and there could be a political drive for a nation to be seen to be leading or of sufficient status to join international projects. Astronomers, especially those within publicly funded observatories, have never been lone stargazers in isolated locations.[8]

Because of the inherently mobile and global nature of astronomy, several of these stories emphasise the requirement that instruments travel or otherwise support the international connections (Bourguet, Licoppe and Sibum, 2002). However, as has been shown in other studies, this mobility is only achieved with considerable planning and care and is always at risk (Schaffer, 2011). In the story by Chinnici (in ‘Object itineraries‘), we see the care taken in transporting even an instrument designed for travel like a marine chronometer. Elsewhere it is evident that it is only by creating connections and sharing knowledge and skill that instruments can be successfully transplanted from one location to another (e.g. Thompson, A camera well-travelled). The designers and makers of instruments are featured in most of these studies, reflecting moments of acquisition, innovation and adoption, but so, too, do the people who were essential to the maintenance and repair of instruments and their material networks. Such work was, of course, part of regular business and key to the successful functioning of instruments, projects and institutions (Denis, 2020).

Whether through exploring an object’s full itinerary, selected moments in its history or aspects of its material nature, all of these pieces work from the assumption that objects are indispensable historic sources that, used alongside text, image and explorations of place and space, can provide additional and sometimes unique perspectives. They often reveal different networks to those that are prominent in written accounts of scientific work or astronomers’ biographies. Here, in addition to considering makers and users of instruments, we have found that objects have led us to the audiences for astronomical science, its services and its spectacle, and the political, commercial and military networks that have both supported and profited from observatory science.

While none of these pieces make overt use of actor-network theory, we can see its influence in the approaches taken and conclusions drawn, as we continue to ‘think with and about things’ (Farías, Blok and Roberts, 2020, p xxi; see also Byrne et al, 2011, pp 10–11). The agency of objects to affect events and outcomes is clear in accounts of failures, or when the transport, placement and use of objects is shown to require specific actions to be undertaken, unique protocols followed, novel connections created, new buildings erected or institutions founded. Equally, these accounts show that, through their appearance and motions, objects have the potential to make a significant impact on patrons and wider audiences. We might note, too, that they also point the historian to new, fruitful and sometimes unexpected directions of investigation.

These stories also demonstrate how objects and people interact within spaces, and that changing locations can change the nature of these interactions. Spaces, entangling the physical with the social, affect the messages and meanings that are created, performed or interpreted by people interacting with objects in particular circumstances (Wintroub, 2010, p 787; Lefebvre, 1991). An early Victorian dining table (Devoy in ‘Observatory networks’) takes on a distinct character when transposed to a space used for the production of official data, for the oversight of a national observatory, or for storing museum artefacts. An electrically triggered model can, when manipulated by a talented lecturer in a grand space evoking civic pride and appreciation of learning, shape understanding of an observatory’s purpose and relationship to the city in which it sits (Raposo in ‘Observatory audiences’).

All of these stories rely on the contingencies of survival of objects and related documentation in observatories or museums.[9] Objects’ survival may rely on positive choices, based on the changing values ascribed to them, but might be a matter of accident or inertia. The authors have been attracted to objects that are underrepresented in collections, for example, the photographic plates discussed by Wilder in ‘Instrumental networks’ or avoided in displays as in the Greenwich examples (Akkermans in ‘Instrumental networks’, and Devoy in ‘Object itineraries’). Fragility or failure are threats to survival in collections just as much as to deployment in original context (compare, for example, the stories by Wilder and Thompson in ‘Instrumental networks‘) while the attractiveness or otherwise of an object also has a role to play (compare the ’black box’ described by Raposo with the model discussed by Higgitt both in ‘Observatory audiences’). Changing audiences can lead to re-evaluations, while the re-evaluations prompted by discoveries revealed by research can change potential audiences (see Biro, ‘Observatory audiences’ and Chinnici, ‘Object itineraries’). Part of this research may be to reveal the gaps and absences that remain, whether in our knowledge or in the surviving material evidence (as becomes clear in Akkermans, ‘Instrumental networks’). These are the known unknowns but, as always, unknown unknowns remain, and objects in themselves can be intractable, limiting or confusing as sources for historians or communication with audiences. Our best hope is to explore all the evidence we have, whether textual, visual, material or oral, and different ways of putting the resulting research to use.

The following articles are both an argument for the use of objects in research and for expanding our appreciation of the range of individuals, institutions and groups that were, to a greater or lesser degree, invested or implicated in observatories, their needs and their outputs. The authors and other workshop participants have been inspired to see just how wide and varied observatory networks can be, and the extent to which they could be mutually beneficial. They tied astronomy into other parts of society and offer us, as historians and curators, a broader range of characters to investigate and share. As well as astronomers and scientific instrument makers, our range of objects allows us to meet physicists, electricians, engineers, geophysicists and chemists, politicians, civic leaders, artists, exhibition visitors, members of learned and local societies, commercial suppliers of photographic apparatus, labourers, mariners, soldiers and even wine and beer merchants.

While our Network is not quite so broad, we have been delighted with the range of participants that we have succeeded in reaching and learning from.[10] We hope that this series of articles will, like the workshops, help the network to sustain and grow and create new collaborations among all of those with an interest in the histories and heritage of observatories.

Acknowledgements

As well as thanking the authors of the following object stories for their work, we would like to express our deep gratitude for the time, thought and wise words that the project advisory group – Ileana Chinnici, Omar Nassim, Pedro Raposo and Simon Schaffer – have contributed to the project. Our thanks also go to the ROG350 Research Fellows, Daniel Belteki and Lee Macdonald, who joined the project management team, and Sally Archer and Fern Aldous at Royal Museums Greenwich, for their invaluable support and advice in managing the project and workshops. Finally, we thank our project partners and local hosts, Katrina Dean (Keeper of Manuscripts and Curator of Scientific Collections, Cambridge University Library), Andy Lawrence (Regius Professor of Astronomy, University of Edinburgh) and Michael Burton (Director, Armagh Observatory and Planetarium), and to all those who contributed to the talks, tours and discussions.