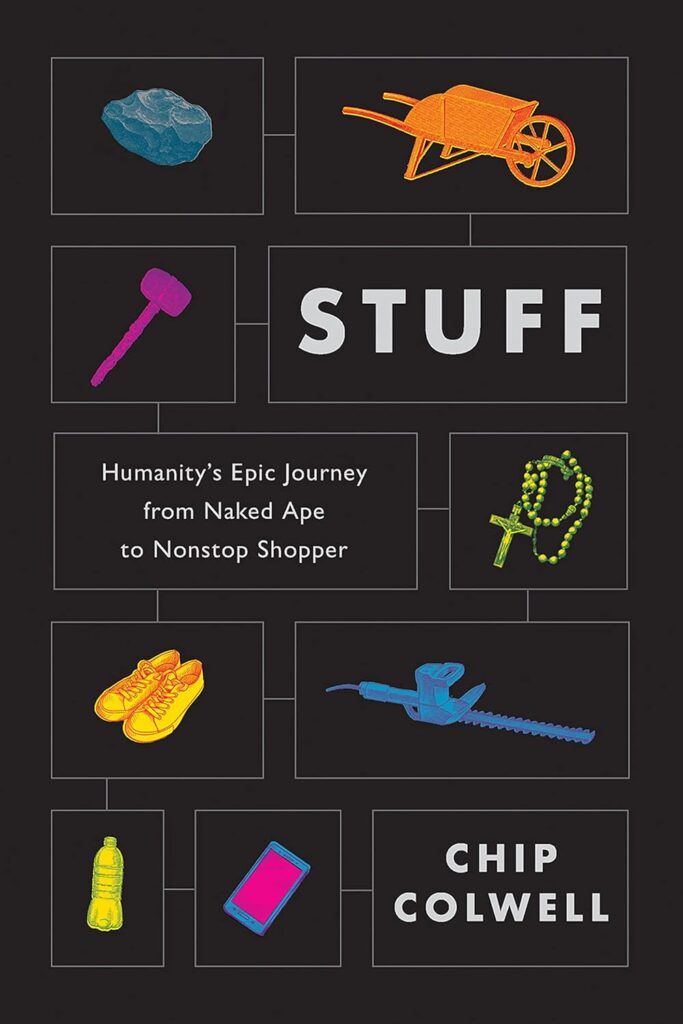

Book review: Stuff: Humanity’s Epic Journey from Naked Ape to Nonstop Shopper by Chip Colwell, Hurst, 2023

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/242106

Keywords

archaeology, ecology, history of art, history of technology, material culture, stuff, things

I pause while writing to survey the things scattered across my desk and count 56. Among them: three Ordnance Survey maps and 15 books (two are duplicates), a radio, a glass of water and an empty coffee mug, three wind-up toys and a Bluetooth speaker. I like my stuff; I like stuff in general. But that seems like quite a lot for a relatively small surface. Things are absolutely everywhere. Similar thoughts have turned into some rather bigger questions for Chip Colwell. ‘How did Homo sapiens also become Homo stuffinensis?’ How have we managed to create a world in which we need so many things while simultaneously suffering terribly because of them? And a little more subtly, how did humans come to make all the things that in turn make us human? His efforts to answer them have ironically resulted in another substantial thing: a 300-page book that tells the story of humanity’s stuff.

He unfolds his ‘epic journey’ in four leaps. The first and second – leaps into making tools and attaching meaning to things – each took thousands of years. The third leap into over-abundance happened across just a century or so. And the fourth – a leap away from bingeing on stuff – hasn’t quite happened yet, but is one Colwell eagerly awaits.

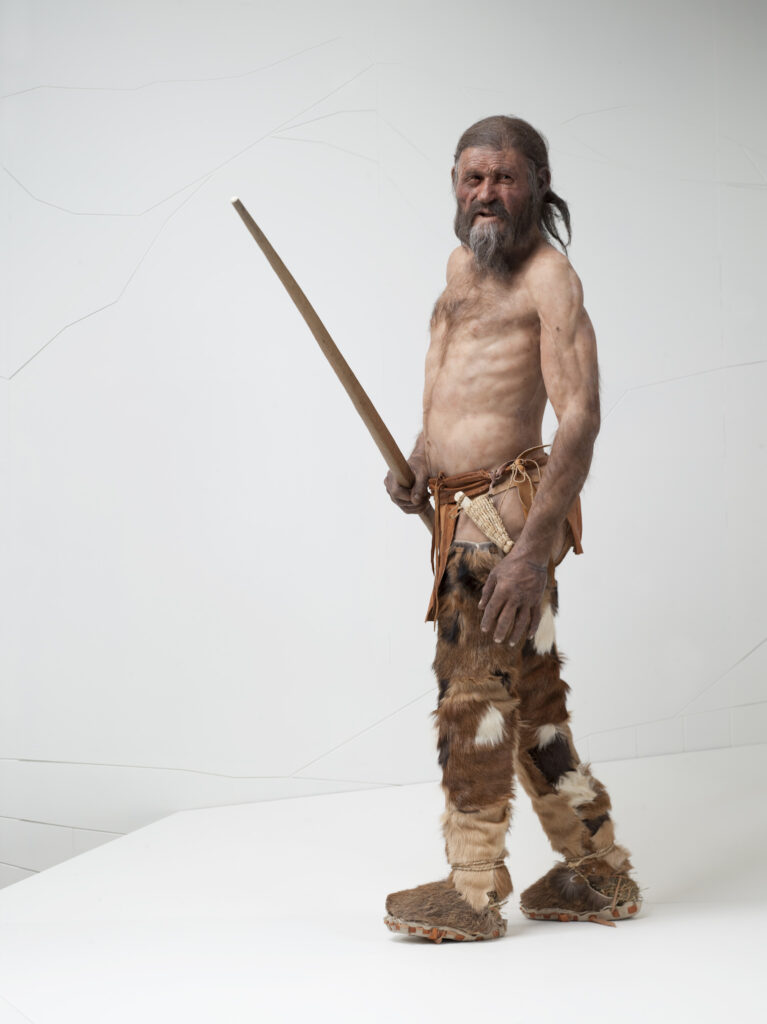

Tools seem first to have been crafted around four million years ago. Though following Jane Goodall’s observations of chimpanzees we’ve had to acknowledge that we share that extraordinary feat with some animals. The more elaborate and distinctive human-like relationship with things – the progressive development of technical skills, for example, and the selection and transportation of raw materials – happened a couple of million years later. And yet another 1.4 million years had to pass before humans started to cook and to make shelters, departing from their nomadic existences. This enabled them to accumulate stuff, which in turn created the possibility of surpluses and debts and, in a nutshell, the beginnings of an economic dimension to life. By the time of the so-called Ötzi iceman – a 45-year-old man preserved for more than five thousand years in an Alpine glacier – a single individual could possess and carry around 400 things, including ‘14 arrows in a quiver, two birchbark containers (with one carrying fire), tinder fungus, a scraper, a boring tool, a bone awl, a retouching tool to make stone flakes, a stone flake, a stone dagger with an ash-wood handle and sheath made from the fibers of tree bark, a mysterious stone disk hung from stirrups of leather, and a copper ax’.

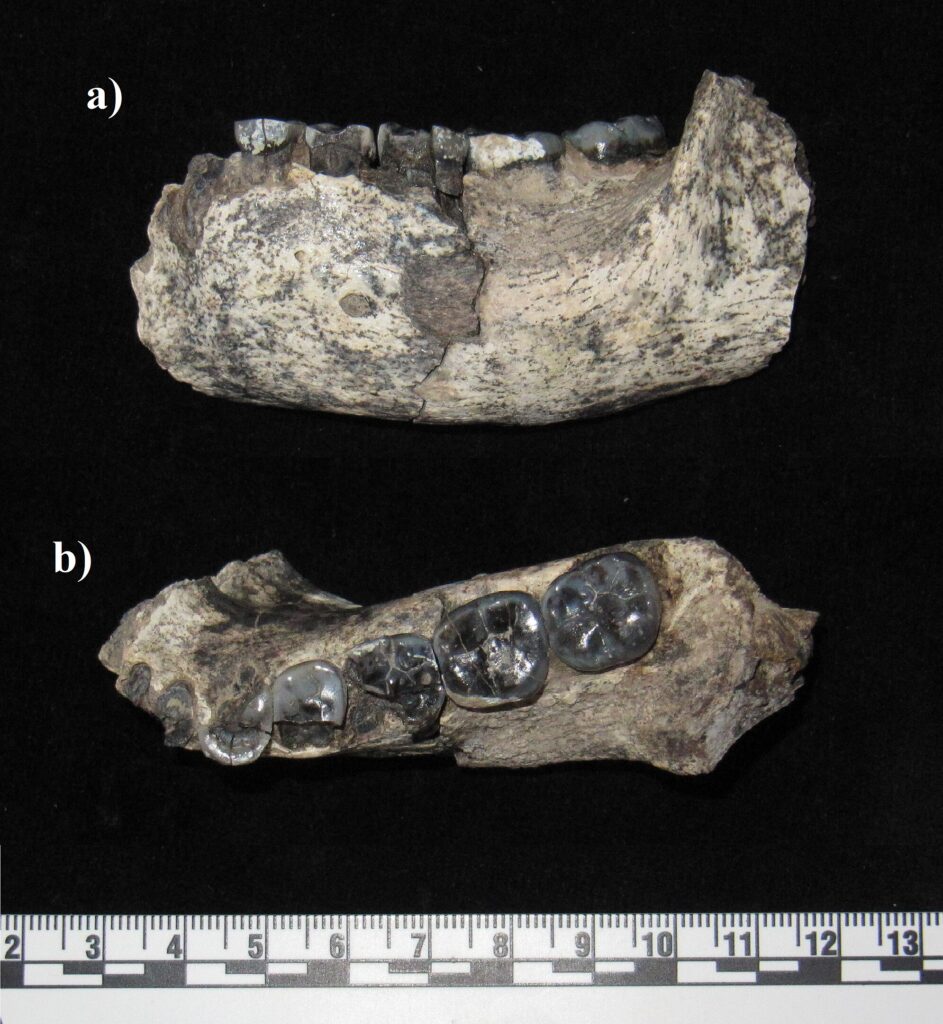

‘With the invention of stone cutting tools [Colwell tells us], our ancient ancestors underwent a series of changes that transformed them from animals who made tools to animals who depended on tools.’ The steady, progressive development of humans as toolmakers took an altogether more significant turn when the causality between people and their things was flipped, when the tools they made started in turn re-making them. Not just the creation of more sophisticated survival techniques and further specialisations in how stone tools were fashioned, this shift marked the transformation of our creative use of things into its own evolutionary force: techno- and organic factors converged to influence the development of the human body and mind. It’s the Ledi-Geraru fossil (a 2.8 million-year-old jaw bone found in Ethiopia) that apparently provides the first unambiguous evidence of human culture and biology merging. The suggestion being that their use of stone tools allowed them to get by with their evidently less strong jaws and duller teeth. Tools then have played an especially powerful role in nothing less than ‘generating our species’. Shaping our minds and extending our bodies, Homo sapiens became Homo faber: ‘a species of makers’.

At some stage in this journey, ‘definitely on this side of 50,000 years ago’, tools became more than just answers to biological needs, more than just means to achieve tasks. Across a span of thousands of years, tools came to outstrip their utilitarian function, taking on meanings beyond themselves, meanings which came to signify art and religion. This is Colwell’s second leap, though one in which, at times, he seems a little less sure of himself. A mysterious silhouette of a humanlike figure, found in Grotte Chauvet in southern France, has been claimed as the world’s oldest painted art. But what actually makes it art? Colwell doesn’t get too bogged down in vexed questions of definition, but he does want us to consider three essential traits that come together in art: ‘an animal instinct for beauty, the desire for self-expression, and the invention of symbolic thinking.’ This combination, he ventures, heralded art as ‘the first type of meaning imbued in objects’. Though as he goes on to acknowledge, this conclusion rests on the only available evidence we have, ‘because art is a traceable material act that archaeologists can find and study – and argue over’. Imaginative speculation it seems is the best we can do with such a slippery subject.

Making art takes time and energy, and this Colwell argues, required a lightening of other essential tasks associated with basic survival. In short, it had to wait for a bit of domestication. Quoting the work of paleo-anatomist Gillian Morriss-Kay, he also ponders whether an evolutionary change in the neural structures underpinning perception might also have contributed to an enhanced aesthetic capacity (Morriss-Kay, 2010, pp 158–76). As self-expression opened up to symbolic expression, so forms of fundamental philosophical thinking followed art: relationships were built up ‘between a thing in the world, a symbol of that thing, and the concept of that thing’. This amounted to thinking through the ‘mind’s eye’ and on to real-world forms carved in a block of stone or painted on a cave wall. The impulse for creating art marked another profoundly transformative stage in our evolution. For just as the human development of toolmaking came to reshape our species, so too with art: the ‘emergence of objects with meaning [led to the] possibility of changing the genus Homo’s evolutionary trajectory’.

From their earliest stirrings, spiritual thoughts and feelings have taken on material expression in statues and altars, offerings and temples. Or might it, Colwell speculates, have been the other way round: ‘could religious objects exist prior to beliefs – in some way the material bringing creed into existence.’ And might the same be true of art, where ‘objects that would become art might have existed before humans and their evolutionary relatives conceived of the idea of art’. And while we’re at it, did art lead to religion, or was it religion that begot art? These issues of cause and effect somehow seem intractable, and maybe even require a different form of conceptualisation altogether. Was there, maybe, a common resonance, a co-emergence, of art, religion and their objective embodiments? Wisely, Colwell doesn’t get sucked too far down this conceptual hole. Instead, he opts to continue unfolding his second leap, plotting how symbolic and meaningful thinking around objects led to the emergence of economic activity and other social relationships, to gift-giving and the wide range of behaviours with which humans have wrapped their objects, allowing us ‘to remember and forget, and to make, and sometimes to exterminate identities’.

From here on Colwell’s tale speeds up, as leap three comes into focus. Up until now, we have mostly been imagining individual ancient ancestors with their individual things: a stone tool or artform or religious prop. But now, as the camera pulls back, larger and larger groups of objects come into view. For here we are witnessing the invention of abundance, and almost immediately it’s premature offspring overabundance. Myriad things are being produced in the context of a mindset that made them make sense, from which the triumphs, but also the perils, of our modern relationship with stuff emerged. It’s a story of increasingly audacious abilities to produce more and more goods and of the galloping needs and wants that emerged alongside them. The by-now-familiar chicken and egg conundrum resurfaces here too: did the things precede these ideas, or…?

Money was one of the most powerful types of object-with-meaning that came out of leap two, which by leap three we find running unchecked as a universal system of value and exchange. Drawing on various well-known chapters in the history of the industrial revolutions (the second as well as the first), Colwell’s particular concern is with scale as he describes shifts that ‘entailed not just what materials were used and what could be made…[but also radical changes in] the amount of stuff produced’. This history of modern science and technology only makes sense in the context of a range of other insights from sociologists, anthropologists and psychologists: a patchwork of borrowed ideas that allows him to describe how household objects came to ‘constitute an ecology of signs’, ones that both reflected and shaped their owners. So that, as consumer researcher Russell Belk has articulated, ‘the sum of our possessions…[has come to constitute] our extended self’ (Belk, 1988, pp 139–68). During leap three then we became our stuff, ‘mindlessly tied to things’.

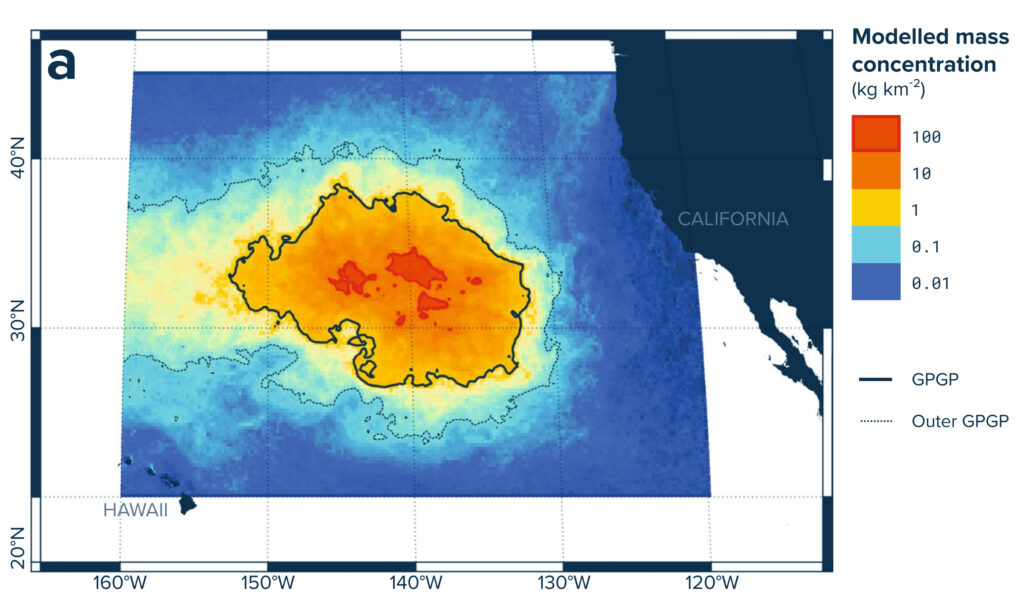

One can almost hear Colwell sigh as he leaves behind the more descriptive and imaginative first two leaps, adopting an increasingly pessimistic tone as he shifts gear. And understandably so, for from here on we’re invited to watch humanity gradually strangle itself in the powerful and magical world of things that it had taken tens of thousands of years to build up to. If only, it is tempting to muse, we had somehow managed to focus on harnessing better and better tools with richer and richer meaning. But instead, greed and the seductive but destructive imperative endlessly to make things easier and more plentiful (but only for a restricted few mind you) takes over. One unintended consequence of that shift has been the emergence of mountains and islands of discarded garbage.

In this gloomy tale, post-Second World War plastics play an especially important role, ushering in the ‘first time that humans were entirely unconstrained by what nature produces’, newly able to manufacture whatever was wanted, where and whenever it was desired, and at whatever scale might seem profitable. Supply went hand-in-hand with demand: the growing global industrial system coterminous with a ‘near-global culture of consumerism’. Things were made because they were desired, but of course those desires had also to be manufactured, and often more as a desire to purchase than one actually to have, use or cherish. The first advertising agency was set up in London in 1786, with modern department stores flourishing in Sydney, Paris, Cape Town, New York and Montreal from the mid-1800s on. The speed of production, promotion and consumption accelerated exponentially from then on.

Quoting the work of psychologist Bruce Hood, Colwell helps us understand the role that ‘miswanting’ had in sustaining the modern world of mass consumerism (Hood, 2019). He lays out the fascinating story of the craze for carpets as an example of ‘conspicuous consumption’ – a term coined in 1899 by the Norwegian American economist and sociologist Thorstein Veblen ‘to describe the practice of buying expensive goods less to satisfy needs and more to display wealth’ (Veblen, 1899). Another crucial ingredient in his tale of how the world got so over-stuffed is the development of ‘planned obsolescence’, the wilful turn from fixing and modifying things to habits of simply replacing them. There’s nothing modern about fashion of course, but its regulation as a form of industrialised group-think was crucial in enabling overproduction to make complete sense. If last year’s stuff could seem silly, ugly or downright embarrassing after a short season or two, and this year’s model affordable (just), then why not simply switch? A diagnostic indicator of this modern pathology is seen in the destructive forms of hoarding. The behaviour itself is not entirely ‘unnatural’: squirrels, foxes, woodpeckers and other animals are also prone to amassing food for the future. Human hoarding then reflects a deep-seated animal urge to make the most of abundance when it appears; but the overwhelming opportunities to over-indulge the instinct that have come during an era of abundance has turned it into a classifiable mental disorder: a ‘persistent difficulty discarding or parting with possessions, regardless of their actual value’, as the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders defines it.

Leap three in this saga of things has, its author argues, put us in desperate need of a corrective fourth leap. ‘So why not welcome another change that reduces overconsumption and halts a world bingeing on stuff?’ Colwell himself declares that he’s ‘lost an interest in possessing things’. A final section entitled ‘Stop Consuming’ begins with a quote from the Buddha: ‘The root of suffering is attachment.’ But his own – honestly described – account of attempting minimalism within his family makes it clear that efforts simply to reverse the trends of the last century or two are not likely to succeed. Consuming somewhat less might result in less being consumed; attempting to consume next-to-nothing can only end in failure. This is the shortest section of his book and by far the least philosophically nuanced or indeed original. Like the rest of us, he seems stuck between realising we are part of the problem and wishing we might, somehow – but it’s not quite clear how – develop a means to ‘reimagine our relationship to stuff’.

Colwell’s epic journey then stalls and somewhat peters out, but he has taken us on an inspiring and winding road to arrive here. To plot and animate it, he masterfully aligns a staggering range of evidence from many different disciplines, pulling them together into three robust parts: his first ‘make-necessary’ section largely drawing on archaeology and parts of biology; the second ‘make-symbol’ section on archaeology and anthropology; and the third ‘make-more’ section mostly on history and sociology. Much of it will, I’m imagining, be familiar to researchers in each separate discipline, but by weaving it into a coherent whole he fashions a fresh, bold and convincing thesis, one which cumulatively suggests an unambiguously affirmative response to a question he poses early on: ‘is being with things simply being human?’ Tools and symbols and consumables all ended up re-making us: biologically, evolutionarily, neurally, morally, socially, culturally and psychologically.

Stuff reads like an important and big book, stretched across a grand narrative in a style we’ve got used to from the likes of Jared Diamond, Yuval Harari, Thomas Piketty, Norman Davies, Simon Schama, etc. Though curiously, none of them appear in Colwell’s bibliography. It’s a compelling story, gripping, exciting, almost dizzying at times, as it loops in any number of fascinating specific instances stirred together with great sweeps of evolutionary, archaeological, and historical developments. There will be new material here for every reader; and while other parts will already be familiar, they will be highlighted from a perspective not considered before. For some, the breezy TED-Talk tone might grate a little. And just occasionally, I found the storytelling tropes a little wearisome – every chapter, for example, starts with a time and location in the writer’s life.

Not surprisingly, given that his subject is nothing less than the entire history of humanity’s experience with things, there are some perspectives, questions and bodies of evidence that might have been relevant but that don’t make an appearance. One, for example, is the recent speculation that the total mass of everything that humans have made and built across the whole globe – the so called ‘anthropogenic mass’ of our technosphere – is about to exceed the mass of all living things, that is the biosphere. Nor does he touch on the idea, put forward by researchers with increasing confidence, that we might in fact have passed a moment of ‘peak stuff’. That is to say, some combination of factors including digitisation and an increasing dominance of the experience economy seem to be leading humanity past the bulkiest and most wasteful period in our evolution. At a less global level, it’s curious maybe that Colwell spends no time talking about how the contemporary world’s over-production came to be distributed: nothing about different national levels of consumption nor indeed anything about poverty. And at a more granular level, he also leaves untouched the psychological aspects of our modern relationship to stuff – the phenomena of ‘transitional objects’ in early childhood, for example, or the later use of objects to develop self-esteem and social standing, or as we near our demise, the nostalgic role specific objects play in allowing us to reminisce about the past rather than look towards the future.

More surprising to me, was how little he talks about museums, especially given how much of his career he’s spent working in them. Actually, Stuff starts in a museum storeroom, with a realisation that ‘just one species invented everything from religious icons to shell money, stone knives to shotguns, coffins to drums’, but after that their role in reflecting and shaping early modern and then modern notions of material culture and the significance of objects and artefacts goes uncommented upon. We certainly hear about some of the amazing things kept in museums, but not about their influence as institutions. Surely museums are the most potent places in which to dwell upon and explore his core contention that we really wouldn’t be humans at all if we were stripped of our stuff. And turning to the fourth leap that he eagerly anticipates, museums could I suspect play their part, symbolically at least, in encouraging us to grapple with the dehumanising material problem we have created: our inability to see trees for all the forests that blind us, unable to isolate important things amongst a blizzard of distractions. Could not museums serve as workshops of a kind for shifting tastes and assumptions, weening us off our addiction to accelerated gazing across one pile of things, one stream of images, after another? Or more grandly, as palaces in which to pursue the charm, excitement, and sometimes compelling urgency available to us when we slow down and study just a few carefully selected things – ones that we don’t even have to own – for just a bit longer, thinking about them just a bit deeper.