Book review: Science Illustration: A History of Visual Knowledge from the 15th Century to Today, by Anna Escardó

Taschen, 2022

To what extent does a book’s thingness matter? How far should we consider books as physical objects, tools to be held in the hand and used – whether in the way intended or otherwise? When I was an undergraduate, at the start of my first year we were all given a copy of the university’s Exam Regulations, a hefty tome that was printed afresh each year. I never saw any of my friends so much as glance inside the book; instead, its customary use was as a doorstop. That’s one thing you can’t do with an ebook.

But if a book is a tool, then at least part of its use is intellectual rather than physical. Which means its thingness is not really relevant. Hence some quarters of the academic publishing sector turning to inferior paper stock and lower quality print-on-demand services in a bid to cut costs. If the ideas inside are the same, who cares? In some scenarios an ebook might prove better than a physical one: if you lose your Kindle, you can be safe in the knowledge that your annotations have been uploaded to the cloud, ready to be synced to your replacement device.

Science Illustration is a book that takes its thingness seriously. It is very big and very heavy, filled with sumptuous, high-quality images that fill whole pages and two-page spreads. In this respect, the book resembles others on the market: a large format hardback, aimed at the so-called ‘intelligent layperson’, presenting a richly illustrated procession of milestones in the history of science. Look at the shelves of any good bookshop or library and there are many books that match this description. The publisher DK alone has published several, including one by the title Science: The Definitive Visual Guide. The market appears saturated.

But Science Illustration does things a little differently. Author Anna Escardó does not present an illustrated history of science but rather a history of scientific illustration, from 1482 to 2021. The book’s central argument is that these images have ‘facilitated the study, classification, development, application, dissemination, and communication of human scientific knowledge’. In this respect the book joins a growing field of work that analyses science as a set of often visually oriented practices.

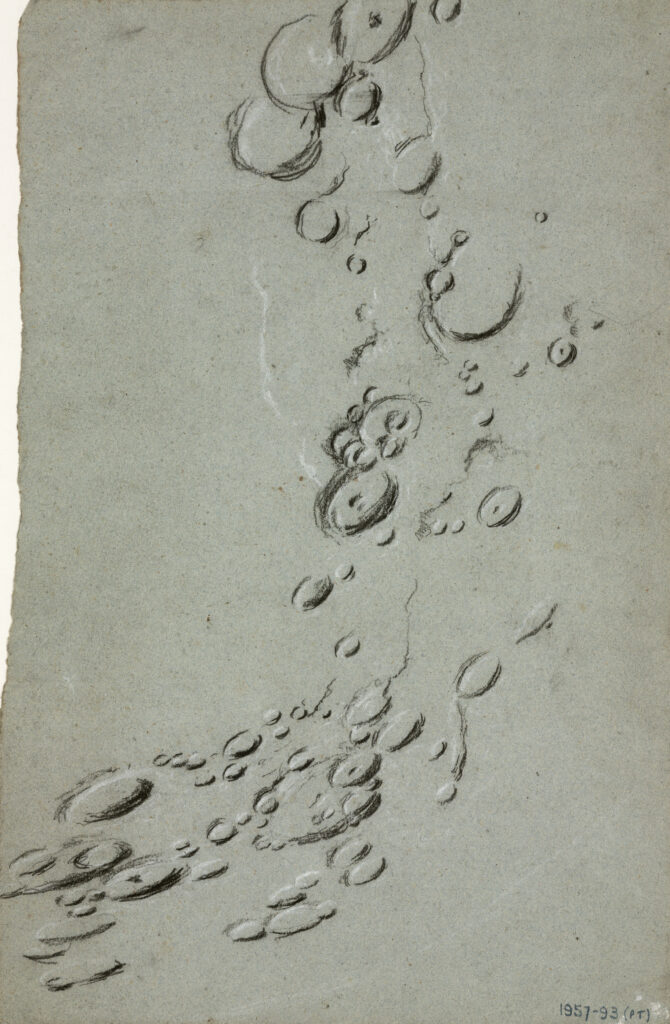

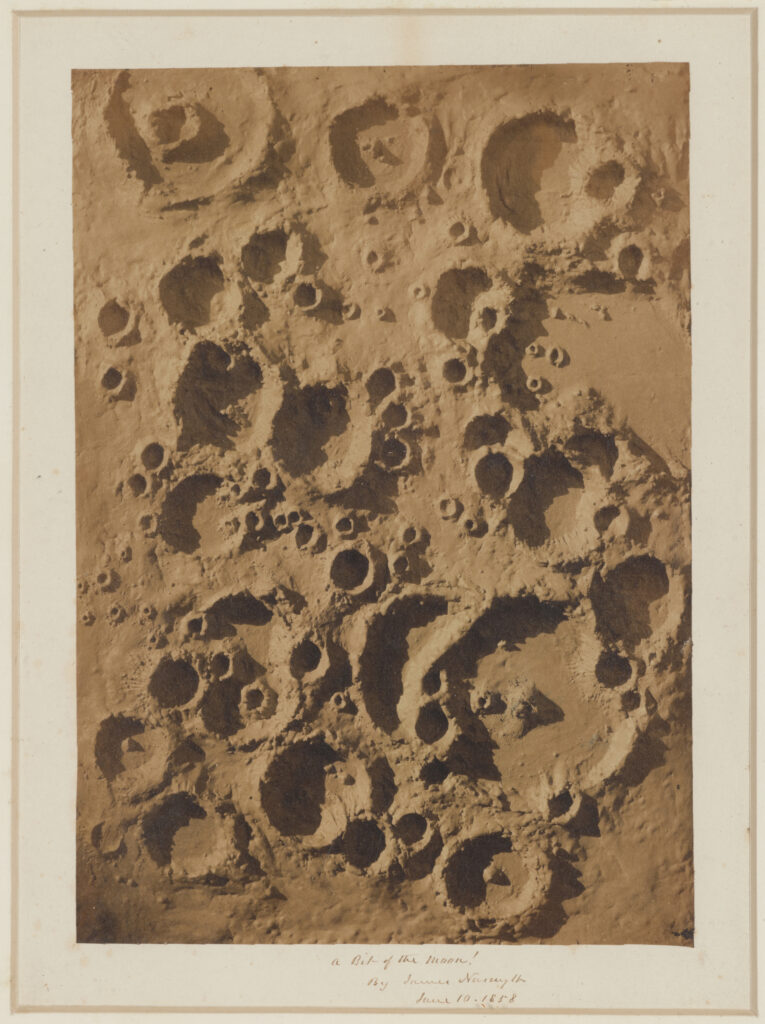

Looking over an issue of Science, Nature, or any other scientific journal, we find page upon page of figures. These visual items are usually proffered as a method of communicating and disseminating the data upon which the research is based. The fact that the figures are often printed in black and white only underscores this idea of the technical image as communicative rather than aesthetic. The US patent system, likewise, requires applications to include diagrams if the patent cannot be understood solely through text. We are used to encountering scientific images in a context that frames them as straightforward means of communication. This book argues that, in addition to communicating and disseminating scientific knowledge, images are also involved in scientific work itself – the ‘study, classification, development, application’ of knowledge mentioned above. Take, for example, James Nasmyth and James Carpenter’s book The Moon (1874), among the first to include photo-mechanically reproduced printed images. The founder of the journal Nature, astronomer Norman Lockyer, remarked how ‘truthful’ the photographs depicting the Moon were. Yet these were not photographs of the Moon at all; with the technology available to Nasmyth, this would not have been possible. Instead, the photographs are of plaster models recreating the Moon’s surface, and Lockyer knew this. Nasmyth created the models from drawings he made during nightly observations of the satellite. Using the drawings, he measured the shadows to calculate the depth of craters and height of mountains; he then used these measurements to create the plaster model. The drawings, now in the Science Museum’s collection, were therefore central to Nasmyth’s study of the Moon, and crucial in his production of photographs that were deemed scientifically truthful at the time. The drawings were put to work, so to speak, in the name of science.

As well as making this argument – about the importance of images to scientific work – Science Illustration also makes the case that scientific illustrations are often aesthetic objects. Escardó is interested in collaborations between scientists and artists. We have the physician Andreas Vesalius creating the anatomical guide De humani corporis fabrica after artist Titian had suggested the idea; the guide’s drawings are attributed to artist Jan van Calcar. In the Science Museum’s collection we have another example of a fruitful crossover of disciplines, in the form of Luke Howard’s cloud studies. Howard created the classification of cloud types, such as nimbus, cumulus, cumulostratus. He made sketches of clouds in an effort to record their different forms and then to disseminate his findings. Alongside these drawings of clouds, Howard also made other studies in collaboration with an artist, in which the clouds are placed above pastoral scenes, with women, children and cattle populating the rolling green hills below (Howard, 1865). In this collaboration between artist and scientist, we find scientific ideas being presented within the constraints of artistic conventions. Aesthetic decisions are made alongside scientific ones. For more information on Nasmyth and Howard’s image making, see Boris Jardine’s article (2014) in Issue 2 of this journal https://journal.sciencemuseum.ac.uk/article/made-real)

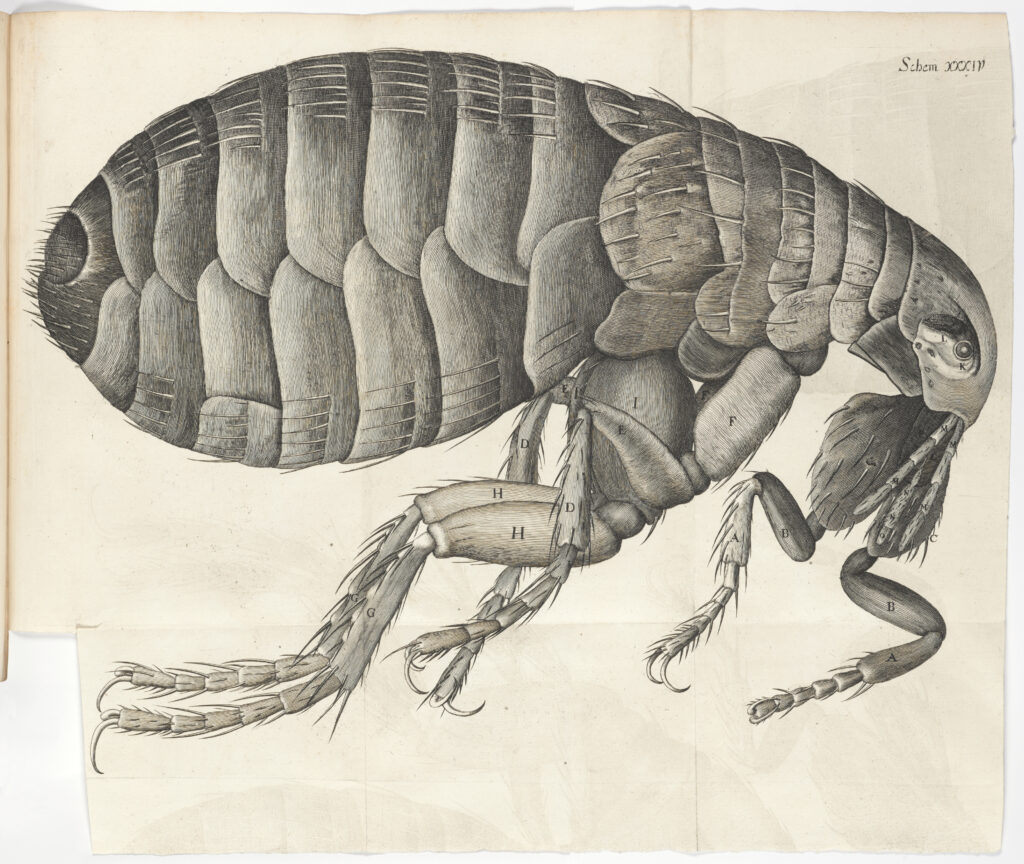

But Escardó also stresses that scientific images aren’t always beautiful. She quotes the physicist James Clerk Maxwell’s maxim that scientific truth is equally scientific regardless of whether it is ‘in the robust form and the vivid colouring of a physical illustration, or in the tenuity and paleness of a symbolic expression’. In scientific domains, illustrations have their own formal conventions, and the specificity of these can often make scientists, rather than artists, best placed to produce images. Escardó cites Robert Hooke’s famous 1665 drawing of a flea under the microscope, from his Micrographia (), and Science Illustration brilliantly reproduces the monstrous image in all its glory. The scale and detail of this and all the other images included in Escardó’s book is excellent; the sheer number and variety of illustrations makes the work a fabulous compendium of visual forms of scientific practice over the last six centuries. There is something here for everyone, with images from all the major branches of science. It is a book that demands you return to it again and again, finding new treasures each time.

Near the beginning of this review I suggested that Science Illustration, like other similar books in the market, is aimed at the ‘intelligent layperson’. But I am not convinced that this is a single, stable, well-defined group of people. Although a popular phrase in publishing circles, it might somewhat cynically be understood as a top-level abstraction deployed by marketers to justify that clear demand exists for a particular publication. As a doctoral researcher working on visual material in the UK’s national museum of science, I am not best placed to have a perspective on the appeal of this book to a wider general public. There was never any question that I would find it to be a delight. Escardó anticipates the problem: might her book not have an audience? In a long and unexpectedly lyrical paragraph in the introduction, she uses the second person to demonstrate how easy it is to go our whole lives without scientifically looking at the world around us. Escardó charts the major milestones in a person’s existence, from conception, to falling in love, having children, growing old, and dying. There are scientific explanations for many things in our lives, yet so often we explain them in other ways, or simply leave them unexplained: ‘You feel fulfilled and complete, but at the same time your serotonin levels plummet, making you feel vulnerable. Whether or not you understand what is happening matters little, since you live the experience all the same as love and affection.’ Escardó takes these two ways of interpreting the world – what she terms poetry and science – and uses them to emphasise how science and art have always been intertwined as competing yet related ways of trying to understand our lives. In this sense, Science Illustration joins a growing field of ‘SciArt’ work, showing the ways that the two fields can be combined productively.

There remains, however, a larger problem surrounding who this book is for. To return to its thingness: this book is very large even for a coffee table book, coming in at a little under A3 size. In most houses it would leave very little space on the table for coffee. And it is heavy, very heavy. It weighs over three and a half kilograms (almost the same as two six-packs of Coca Cola cans). The size and weight greatly limit the scenarios in which you can read it. I struggle to picture a casual reader picking it up on a whim, dipping in and out. A reading session demands some pre-planning, and a lot of table space. So, if not a perfect fit for the popular market, might the book appeal to the academic market? There will, of course, be some interest among certain researchers, especially those working on the intersections between art and science such as myself. Yet the book’s tone – knowledgeable but approachable – is not quite scholarly enough to warrant it being considered a must-have reference volume to be added to all academics’ shelves. Moreover, the design of the volume suggests that academia is not the target market. Who then, is this book for?. To return to the question with which I started: to what extent does a book’s thingness matter? Perhaps the usual answer nowadays is: not a lot. But Science Illustration’s physicality is so cumbersome and awkward that its thingness is difficult to overlook. This is a shame, because inside that awkward exterior lies a substantial body of knowledge – and a vast array of visual delights.