Philanthropy, industry and the city of Manchester: the impact of Sir Joseph Whitworth’s philanthropy on Manchester’s built environment

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/211608

Abstract

Sir Joseph Whitworth was one of the most successful industrialists of nineteenth-century Manchester and made significant contributions to the development of engineering through improving precision and standardisation in machine tools. He also had an important and hitherto largely neglected impact on Manchester’s built environment through his posthumous philanthropy. This paper studies the interventions in the cityscape funded by Whitworth’s substantial legacy to assess how they influenced its development. Through the use of spatial analysis, I highlight the pivotal role of Whitworth and his legatees in the establishment of the Oxford Road educational corridor. Bringing together the history of philanthropy and the history of the built environment enables a reassessment of Whitworth’s ideological intentions and provides the means to expand the scholarly discourse on the development of the built environment to encompass the influence of individuals.

Keywords

built environment, industry, legacy, Manchester, philanthropy, urban, Whitworth

Introduction

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/This article explores the impact of Sir Joseph Whitworth’s philanthropy on Manchester’s urban environment, with two objectives. Firstly, it aims to demonstrate that synthesising hitherto disparate areas of research, the history of philanthropy and the history of the built environment, can uniquely illuminate the history of a city in ways that these two approaches in isolation have not. Secondly, it seeks to model an approach to urban history which refocuses attention on the study of forces affecting the development of a site at the micro level of individual influence. Whitworth is a particularly revealing figure to examine. He was a leading industrialist of late-Georgian and Victorian Manchester and his substantial legacy partly or significantly funded many of the city’s most important educational, cultural and medical institutions, many of which are extant today. Studying the buildings his legatees chose to fund can help us understand the vital – and currently under-recognised – role that Whitworth played in establishing the Oxford Road area as an internationally significant educational corridor. The most obvious ramification of this reappraisal of Whitworth’s legacy is to demonstrate the need for museums to reinterpret Whitworth and objects relating to him, to reflect this larger understanding of his influence beyond innovation in engineering. By introducing the examination of philanthropy into wider critical discourse concerning Manchester’s historical development, this study highlights how the idiosyncratic interests and preoccupations of certain individuals can materially shape the physical environment of a city.

Philanthropy in late Georgian and Victorian Manchester is a topic that has received extensive scholarly attention. How it impacted on the built environment, on the other hand, has been relatively neglected. Although much of the scholarship touches on philanthropically funded buildings and their history, this is rarely the focus. Francis Hawcroft’s history of the Whitworth Art Gallery is largely concerned with the foundation of the institution and development of its collection, with the brief mention of the building itself being limited to description (Hawcroft, 1985, pp 212, 214–15, 222–224, 227, 229). Similarly, Alan J Kidd (1985, pp 58–61, 63–64) and Michael E Rose (1985, pp 110–112) are primarily interested in philanthropic activities and any reference to buildings relates to their purpose rather than their place within the built environment. Michael Harrison’s (1985, pp 127, 136, 138, 141) exploration of T C Horsfall’s Manchester Art Museum largely follows the same pattern, except for one tantalising reference to the Museum as ‘one part of Horsfall’s plan for an ideal Manchester’, which he neglects to elaborate on. James Moore (2018, pp 76–77) explores the reasoning behind the location of the Manchester Royal Institution (now Manchester Art Gallery) but does not assess the impact of the building on the cityscape. Gordon Stewart Marino’s (2012, p 29) PhD thesis on the archaeology of philanthropic housing is a more significant exception, focusing on the built environment through his archaeological approach. Overall, however, buildings funded by philanthropy have tended to be examined as part of a narrative history of a person or organisation, rather than within the wider context of the built environment.

Historical and archaeological studies of Manchester have engaged with the physical development of the city and the factors that have influenced its growth and change. Gary S Messinger (1985, pp 5–16, 115–20) provides a succinct overview of how the city and its surrounding area evolved in the second half of the nineteenth century, highlighting the impact of industry and its resultant wealth on the changing cityscape, but does not go into specific details. A broad history of Manchester’s development, and the forces that guided this, is provided by Kidd (1993) but, concerned as his study is with the whole span of settlement from 77 CE through to the late 1980s, he necessarily limits this to providing an overview rather than a focused picture. Rose, Falconer and Holder’s (2011, pp 47–57) history of Ancoats highlights several philanthropic interventions in the built environment but is largely uninterested in the implications of these buildings for their wider physical context. This article will expand our knowledge of the development of built environments by studying the influence of charitably funded buildings, approaching the topic by focusing on a single, highly influential individual.

Sir Joseph Whitworth

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/211608/002Joseph Whitworth was one of the most successful of Manchester’s many nineteenth-century industrialists. His obituary in The Times (Anon, 1887b) described him as ‘the greatest name of our time in mechanical engineering…whose efforts have left a permanent impress upon the workshops, not only of this country but of the whole civilized world’. These plaudits were a result of Whitworth’s endeavours to improve precision and standardisation in machine tools. He designed measuring machines capable of measuring to one millionth of an inch (De Liso, 2006, p 481), devised a method of manufacturing truly plane surfaces, and developed a system of standardised screw threads that was subsequently adopted as the British standard (Seccombe and Buchanan, 2007), thus greatly aiding the move towards mass production and interchangeable parts (Anon, 1887a). Whitworth’s drive for improving on existing designs also led him to manufacture arms, most famously the Whitworth rifle with its hexagonally rifled barrel and custom-made bullets that gave it impressive accuracy and range (Ray, 2010, pp 43–44). Starting in a relatively humble city-centre workshop on Port Street in Manchester, Whitworth built his business up quickly and moved to a larger factory site on Chorlton Street (Atkinson, 1996, pp 41, 48–49). His company later moved the works out to the suburb of Openshaw (Atkinson, 1996, p x). The expanding business enabled him to build a house he called ‘The Firs’ in the southeast Manchester suburb of Fallowfield (Historic England, 1994). Later he bought Stancliffe Hall, a country estate in Derbyshire, in addition to his Fallowfield house (Atkinson, 1996, p x).

Whitworth’s engineering prowess and booming business made him a very wealthy man. At his death in 1887, he left a residuary estate totalling more than £1,277,000 to three legatees to use as they wanted (Kilburn, 1987, pp 35–37). This would be the equivalent of over £143,000,000 in 2019 (Officer and Williamson, 2020).[1] This represents a significant legacy for the period in Britain. Such large legacies were a relatively rare occurrence until the end of the nineteenth century (Cunningham, 2020, p 165), while charitable subscriptions during life were the usual form of philanthropy (Morris, 2005, p 132). Although the money legally belonged to the legatees, Whitworth stated in his will that they were ‘each of them aware of the general nature of the objects for which I should myself have applied such property’ and its use for charitable objectives was implicit and supported by earlier codicils.[2] Whitworth specifically eschewed creating a trust to apply his residuary estate for charitable purposes in order to avoid the pitfalls described by Chantal Stebbings (Stebbings, 2001, p 163), in particular the inflexible interpretations of the testator’s will, deviation from which could see trustees liable for breach of trust. This foresight undoubtedly paid off by enabling the legatees to successfully defend against 11 cases in the Court of Chancery (Darbishire, 1908). Unlike fellow philanthropic industrialist Andrew Carnegie’s Carnegie Corporation of New York, which would fund various activities, Whitworth’s avoidance of a Trust required him to put his absolute confidence in his three legatees, with the only specific endowments relating to causes like the Whitworth Scholarships. Thus Whitworth placed great faith in his legatees – his second wife Lady Mary Louisa Whitworth, Robert Darbishire and Richard Christie (Atkinson, 1996, p 301)[3] – to apply the money according to his wishes, which according to Darbishire (1908) were communicated in numerous discussions from 1884 until Whitworth’s death. Although Whitworth had several relatives, some of whom received small gifts in the will or from the legatees, he had no heirs so, after funding several projects that were jointly decided upon, the remainder of the estate was split between Darbishire, Christie and the executors of Lady Whitworth, who died in 1896, and was generally used to increase their own contributions to their individually chosen causes.

It is important to point out that the following exploration of how Whitworth’s vast legacy was used charitably is not intended to valorise the man. Though most of his fortune was amassed through the manufacture of machine tools and the armaments side of the business was not particularly profitable, Whitworth designed and manufactured rifles that saw action in the American Civil War (Atkinson, 1996, pp 264, 271). Both the Union and Confederate armies purchased artillery from Whitworth, but it was the rifles he sold to the Confederacy that were used to great effect in their fight to maintain enslavement as a key component of their economy (Ray, 2010, pp 48, 45–46). This article follows contemporary commentators and scholars of the history of philanthropy in questioning the motives and altruism behind Whitworth’s philanthropy (Cunningham, 2020, p 166; Owen, 1964, pp 103–104, 136, 143–144, 164–167).

In order to explore how the philanthropy of Whitworth impacted on the built environment in Manchester, this article will focus on the infrastructure Whitworth funded and its purpose, the analysis of the geographical spread of buildings funded by Whitworth in relation to each other and to other key locations, and the chronology of when Whitworth’s charitable giving resulted in the erection of buildings or other changes to the urban landscape. This comparative approach not only enables us to assess how his philanthropy tangibly affected the city, but more widely illuminates the extent to which the physical development of places can be influenced by individuals’ idiosyncratic passions and interests.

Interventions

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/211608/003Whitworth’s legacy funded an array of activities in addition to buildings but this article focuses on the outputs which impacted the built environment. These interventions, funded wholly or substantially by Whitworth’s fortune, can be loosely grouped into categories based on their function. However, as I will show later, these categories can be misleading in terms of the legatees’ real intentions for the buildings. The buildings with an educational purpose were the Whitworth Engineering Laboratories and Whitworth Hall, both at Owens College (now the University of Manchester), Manchester Municipal Technical School, Openshaw Free Library, and Darley Dale Whitworth Institute. Whitworth’s Fallowfield home ‘The Firs’ was also left to Owens College. Institutions which focused on health and medicine included Manchester Royal Infirmary on its Oxford Road site, the Cancer Pavilion and Home, Whitworth Cottage Hospital, and Whitworth Baths. To support culture, Whitworth’s legacy funded the Whitworth Institute and Manchester Museum. The legacy also supported provision of green space in the form of Whitworth Park, and Darley Dale Whitworth Park.[4] Located in Darley Dale near Whitworth’s country estate of Stancliffe Hall, Whitworth Cottage Hospital and Darley Dale Whitworth Institute and Park are outside the geographic scope of this article and so will not be examined except where their study provides a useful point of comparison with buildings in Manchester.

The educational nature of the first grouping is fairly self-explanatory and uncontentious. The categorisation of many of the other buildings, however, is open to debate. Manchester Museum is also part of the University of Manchester (and previously Owens College) and has, from the start, been used for education and research (Manchester Museum, n.d.). Although the Whitworth Institute is now solely an art gallery, the original vision was for a hub of technical as well as artistic education. The site was to house a museum of industrial and fine art and commercial products, a technical school and an art school,[5] although the plans for locating the technical and art schools in the park had been dropped within a couple of months of the initial proposal.[6] When it was incorporated, in 1889, education was the primary purpose of the Whitworth Institute.[7] It is important to recognise, therefore, that both of these buildings were intended to have a significant educational function.

From contemporary discussion of the gift of land that the Manchester Royal Infirmary is built on, it is clear that the site was chosen for its proximity to Owens College in order to improve medical education there. In letters to local newspapers, subsequently published together as a pamphlet, Charles Hughes criticises the behaviour of the legatees in regard to their offer of a site for a new hospital. He states that ‘A very large body of practical opinion inclines to the belief that everything that is necessary can be provided upon the present site’,[8] which suggests that the location could only be to benefit education if there was no medical necessity for the move. A report in the Manchester Guardian on the withdrawal of an earlier offer of a new hospital and partial endowment stated that the offer ‘was not primarily to benefit the sick poor of Manchester, but “to promote the efficiency of medical education”’ and ‘that the Whitworth legatees had declined to consider any proposal to devote funds to the extension of the hospital accommodation on the Infirmary site’ (Anon, 1889b). Additionally, the Cancer Pavilion and Home was founded on its original site just off Oxford Road with the intention of establishing strong links with Owens College and its medical school, and the aim of researching cancer (Anon, 1891). Once this more nuanced view of the purpose of these buildings is taken into account, it would be more accurate to suggest that 75 per cent of the interventions philanthropically funded by Whitworth had a significant educational function in mind.

Interactive map showing the interventions in the built environment funded wholly or substantially by Whitworth. Created using QGIS. Base map data: © OpenStreetMap contributors, SRTM | map style: © OpenTopoMap (CC-BY-SA)

Educational corridor

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/211608/004As Figure 1 illustrates, the majority of Whitworth’s Manchester buildings were clustered along Oxford Road (indicated in blue). Of these seven interventions, all but Whitworth Park were intended to serve an educational purpose. As a vocal proponent for Owens College and scientific education (Kilburn, 1987, p 35), it is unsurprising that much of Whitworth’s money should be spent on the college at its new site on Oxford Road. However, although, as we have seen, the proximity to Owens College was a key factor in the legatees’ decision to gift land on Oxford Road as the site for the new Manchester Royal Infirmary, whether Owens College played a role in the choice of site for the Whitworth Institute and Park remains unclear.

By supporting Owens College and choosing sites for these other organisations along Oxford Road, Whitworth’s legatees bolstered the presence of existing institutions, like that of the School of Art, and created a concentration of educational establishments. Subsequently, Saint Mary’s Hospital, Manchester Royal Eye Hospital and Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital were constructed next to the Manchester Royal Infirmary as further teaching and research hospitals. Manchester Metropolitan University and the Royal Northern College of Music have also taken up residence on, and spread back from, Oxford Road. Owens College, now the University of Manchester, has additionally expanded to encompass a large part of the streetscape on both sides. Thus Oxford Road is now dominated by educational establishments forming a ‘corridor’ of knowledge, innovation and culture (Oxford Road Corridor, 2020). By providing funding and stipulating locations, Whitworth’s legatees, knowingly or not, played an important role in the early development of this corridor. Both David Owen (1964, pp 474–475) and Hugh Cunningham (2020, pp 163–164, 166–167) have suggested that Victorian philanthropy followed remarkably conventional lines in terms of what was financed and Whitworth was certainly no exception to this. Nevertheless, however unimaginative the objects of his philanthropy might have been, the institutional manifestations of his personal passion for education significantly shaped Manchester’s built environment. It is worth noting, however, that Whitworth’s influence is restricted to the purpose and location of the buildings with no shared design language to link them; the physicality of the buildings instead aligns with their immediate grouping, for instance the Waterhouse architecture of Owens College, which may go some way to explaining why the extent of Whitworth’s impact on this area of the city has gone unacknowledged for so long.

Commemorating the man?

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/211608/005The fact that all of the interventions in the built environment discussed above took place after Whitworth’s death might be construed as evidence for the motivations of his legatees rather than Whitworth himself – specifically, that their intention may have been to create lasting, tangible monuments rather than to support his chosen causes. The evidence, however, provides a more complex picture.

In a letter of February 1888 regarding the founding of the Whitworth Institute, Christie promised at least £50,000 in addition to the initial offer of land and expressed ‘the hope that the name of Sir Joseph Whitworth should now be connected with the Park and the Institute’.[9] Although an acknowledged intention of the Whitworth legatees was that the Institute would be a memorial to Whitworth, the fact that they only requested that Whitworth’s name was associated with the Institute and Park once additional donations had been promised, several months after the Institute was initially proposed, indicates that this was not their principal goal.[10] The belated attachment of Whitworth’s name to the Institute suggests that it was not the legatees’ primary intention to impact the built environment in order to commemorate Whitworth. Neither was it Whitworth’s own intention as he did not philanthropically finance any buildings during his lifetime. The lack of interest in the aesthetics of the buildings funded seems to support my contention that less importance was placed on memorialising than on other priorities. Draft Outlines of a Scheme from February 1888 included stipulations as to the orientation of the Whitworth Institute buildings to give optimum natural light but made no mention of details of architectural style.[11] In a Galleries and Museums sub-committee report of October 1888, the Whitworth Committee, which administered the Whitworth Institute, ‘recommended…that the required accommodation shall be provided, and the more costly finishing of the exterior deferred’.[12] If memorialisation was the main motivation, one would expect to see greater attention paid to the aesthetics.

Nevertheless, the desire to commemorate Whitworth was undoubtedly one concern and can be seen in the context of Simon Gunn’s (2000, p 26) assertion that the desire to create ‘an urban public sphere’ was an important feature of the bourgeois culture of the nineteenth-century middle class. By adopting aristocratic norms of charitable work and giving, philanthropy enabled the middle classes to acquire and consolidate influence and solidify their position at the top of the urban social hierarchy (Geddes Poole, 2014, pp 6, 10–11; Gunn, 2000, p 23). Andrea Geddes Poole (2014, pp 10–11) has argued that, for many Victorians, philanthropy and public service were closely tied to citizenship and were thus embraced by middle-class women as the means by which they could shape social reform and forge a respectable public life. It seems likely that, for wealthy middle-class men, who did not encounter the same barriers to public life and positions of influence and authority, the funding and construction of public buildings and amenities was a tangible and lasting demonstration that they were fulfilling their civic duty. This depiction of performative philanthropy is also linked to the popular ‘associational culture’ of the nineteenth-century middle class, where organisations such as Literary and Philosophical Societies and Mechanics’ Institutions acted as important arenas for the acquisition and consolidation of power (Morris, 2005, p 31). Financially supporting associations like these must have contributed to Whitworth’s high societal standing but the posthumous funding of buildings would not have the same beneficial impact for Whitworth – after all, one cannot wield societal power after death. It is worth considering whether the legatees were able to leverage the same benefits by directing the dispersal of Whitworth’s estate.

Intentions

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/211608/006However, philanthropy as a demonstration of citizenship, or in conjunction with associational culture to build and maintain middle-class power, is not only achievable through funding buildings, as is amply demonstrated by Whitworth’s support of various causes during his life. It is therefore important to consider the other reasons for the proliferation of buildings funded through Whitworth’s legacy. The evidence suggests that a lack of infrastructure and facilities necessitated it. Many of the causes supported by his legacy were ones endorsed by Whitworth. For example, Whitworth was a keen supporter of the Mechanics’ Institute that was founded in 1824 at premises in Princess Street (Kilburn, 1987, p 35). By the time of his death in 1887, the organisation had outgrown the site.[13] After at first proposing to build a new technical school alongside the Whitworth Institute in Whitworth Park, when the old factory site on Sackville Street was requested instead, the legatees agreed to gift it along with a grant (Darbishire, 1908), resulting in the aforementioned Manchester Municipal Technical School.[14] Similarly, the Whitworth Engineering Laboratories provided much-needed facilities for the Engineering Department of Owens College (University of Manchester Library, n.d.),[15] for which Whitworth had funded the first professorship (Atkinson, 1996, pp 288–289). According to a Manchester Guardian cutting of August 1888, the legatees were aware of ‘a pressing and immediate want of baths at Openshaw’ (Anon, 1888) and thus financed the building of an ‘unusually comprehensive’ public bath close to the Openshaw Works (Anon, 1889). Even when the need was not necessarily an external one, for example in the case of the Royal Infirmary, the desire of the legatees to improve medical education required that they provide land for a hospital closer to the college. At the time that the legatees were deciding what to spend Whitworth’s legacy on, a need arose for infrastructure and facilities to support activities that Whitworth had championed during his life. The activities promoted by Whitworth also seem to illustrate his engagement with contemporary debates about philanthropy and the potentially pauperising effect of certain kinds of giving, such as alms giving (Owen, 1964, pp 136–137; Cunningham, 2020, p 166). Avoiding these so-called pauperising benefactions naturally steers a philanthropist towards activity that is more likely to require infrastructure and facilities. Choosing to meet this need may have provided Christie, Darbishire and Lady Whitworth with the means to further Whitworth’s chosen causes while also leaving lasting memorials to him as a man and a citizen.

A true philanthropist?

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/211608/007Christie, Darbishire and Lady Whitworth clearly had great latitude in deciding how to spend the legacy and so their agency in this philanthropy must be acknowledged, along with the philanthropic context of Victorian beliefs in the ‘worthy’ and ‘unworthy’ poor and the civilising effect of culture (Weiner, 1994, pp 10–15, 157–8). However, as has already been shown, the buildings funded after Whitworth’s death align with his well-evidenced preoccupation with furthering education. From his involvement with the Manchester Mechanics’ Institution (Tylecote, 1974, pp 76–77) and endowment of the Whitworth Scholarships to bequests and statements in superseded versions of his will,[16] Whitworth’s actions show that he was deeply concerned with education, particularly in technical subjects. This was also well recognised by his contemporaries; one obituary in the Manchester Guardian, for instance, claimed that ‘The name of Whitworth is inseparably connected with the progress of technical education in England’ (Anon, 1887a). This provides evidence that Whitworth’s interests were a major influence on how his legacy was spent. We should therefore consider Whitworth at least partially responsible for the impacts on the built environment executed through his legacy.

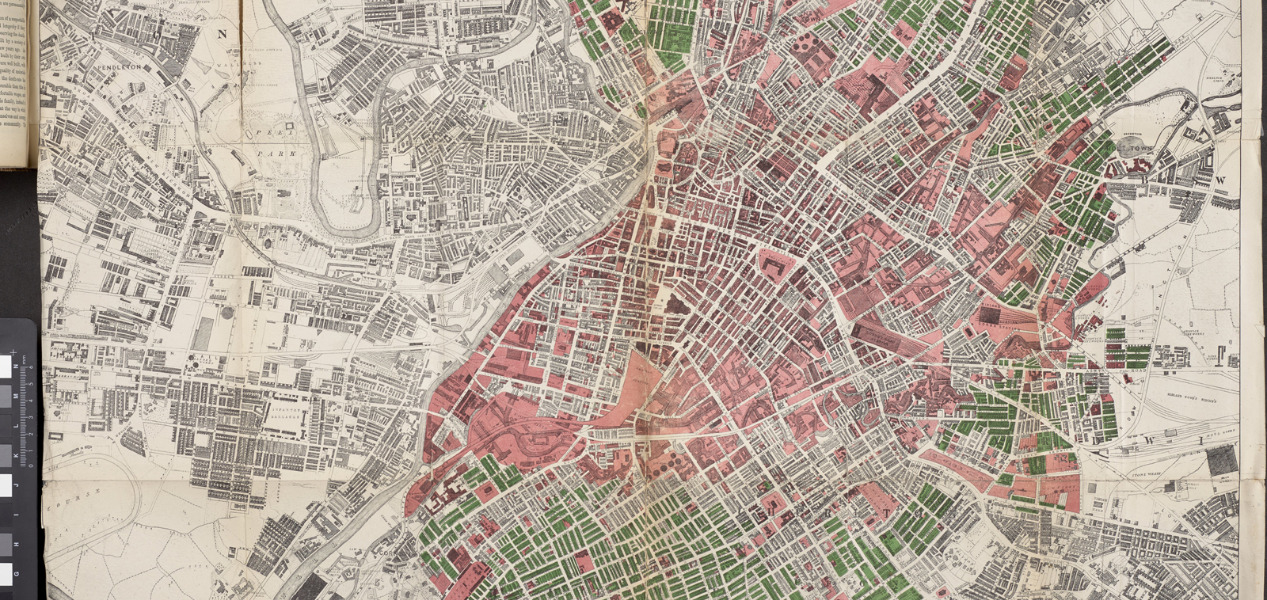

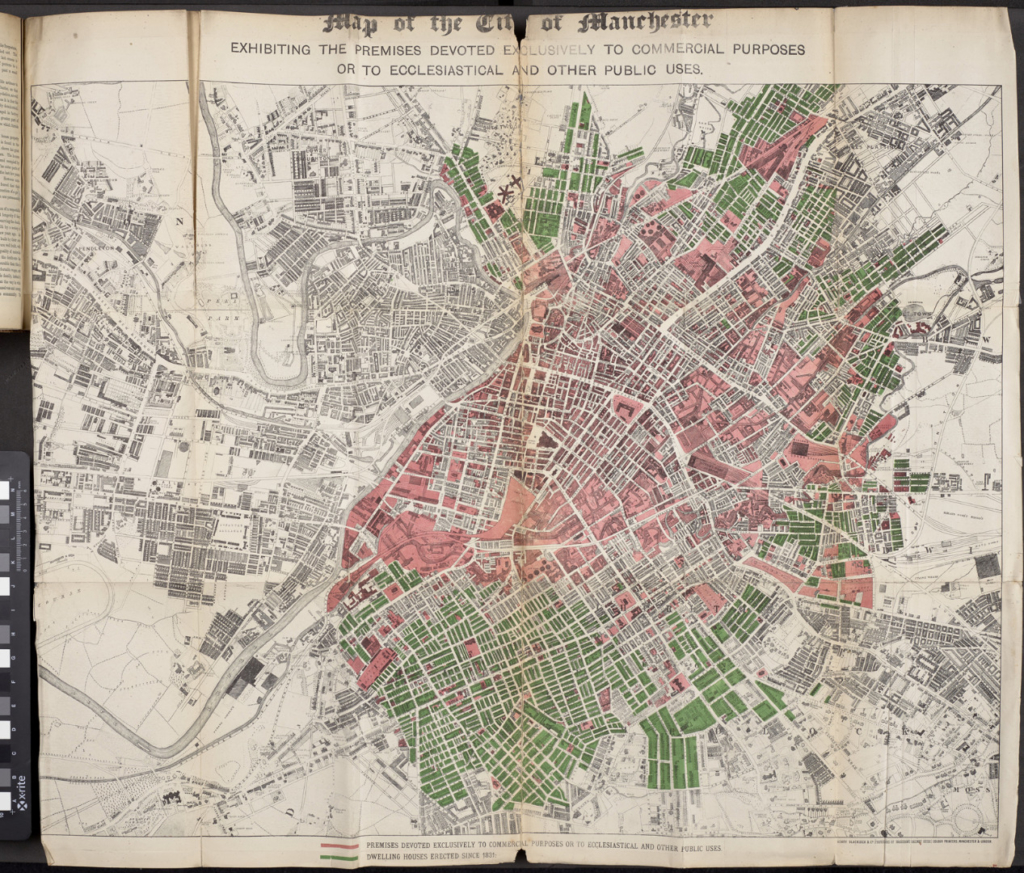

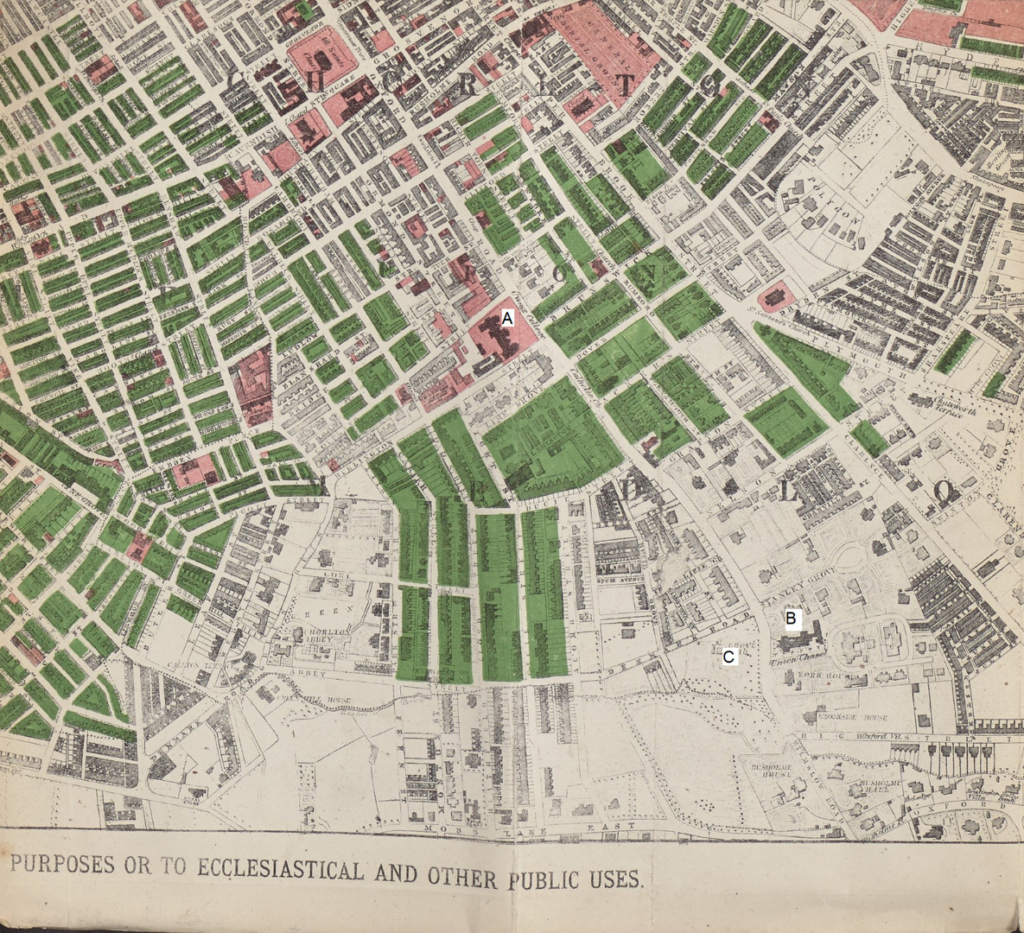

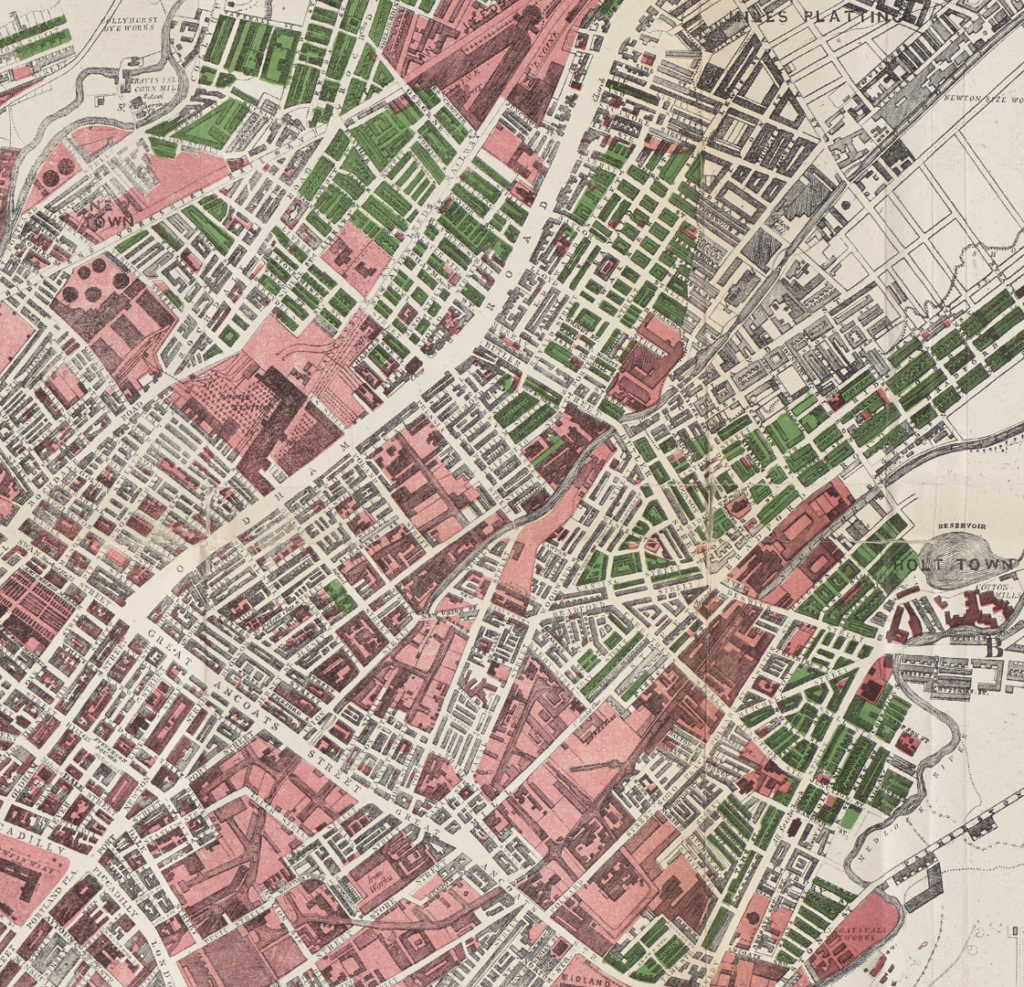

Further examination of Whitworth’s impact on the built environment requires consideration of any additional social motives. As we have seen, a large proportion of Whitworth’s interventions are clustered close to Owens College. At the time of building, this was not a densely populated area of working-class housing. From a map of 1876 (see Figure 2), we can see that the Oxford Road area from Owens College, out past the hospital site, to the Whitworth Institute (see Figure 3), was relatively underdeveloped when compared with a tightly packed residential district like Ancoats (see Figure 4).[17] This suggests that the primary concern was not serving the worst off in society, otherwise the chosen sites would have been in more working-class residential areas or at the very least in more central locations for ease of access. By contrast, T C Horsfall stated that his aim was to provide access to art for the working class through his Manchester Art Museum (Harrison, 1985, p 123). Consequently, Horsfall chose Ancoats Hall in the heart of poverty-stricken Ancoats as the collection’s permanent home in 1886 (Harrison, 1985, p 127).

The technical school was constructed in a central location, providing ease of access for people from across the city. However, this was a deviation from the initial plan. The legatees originally proposed to move the technical school from Princess Street in the city centre to the Whitworth Park site.[18] This suggestion was heavily criticised as failing to meet the needs of the working people intended to use it.[19] It also ran contrary to the contemporary philanthropic trend of trying to tackle poverty by bringing culture into the heart of slum areas as detailed by Deborah Weiner (1994, pp 157–158) in her description of the University Settlement Movement in London. Given that the proposal of the central Sackville Street site where the school was eventually constructed did not come from the legatees,[20] it is evident that the legatees were not particularly sensitive to the requirements of the working class. Horsfall’s decision just the year before to locate his art museum for the working class in Ancoats, where his intended audience would be able to readily access it, along with the University Settlement Movement, indicates that contemporary philanthropists were thinking about the needs of those they wanted to help where this was a key concern. The legatees must have been aware of Horsfall’s work so we can infer from their failure to attempt to discover the requirements of potential working-class attendees of the technical school that helping the working class was not their highest priority.

The very limited charitable expenditure in Openshaw – focusing only on the baths and library – indicates that Whitworth and his legatees were not principally interested in benefitting a more specific section of the working class, namely Whitworth’s workers, either. It is interesting, and perhaps surprising, that so little of Whitworth’s money was spent on works that would have directly benefitted his employees. Whitworth’s decision to offer shares in his newly limited company to employees rather than on the stock market is described by his biographer Norman Atkinson (1996, pp 296–297) as unorthodox but as having the aim of sharing the wealth of the business and giving them a voice ‘in the policy-making of the company’. Furthermore, one of the company objectives was ‘The establishing, managing and assisting of schools, libraries, banks, dispensaries, infirmaries, provident societies and clubs for the benefit of persons employed by the company’. Yet only Whitworth Baths and Openshaw Free Library were built in a location where it would primarily benefit the workers at the Whitworth factory (see Figure 1) (Anon, 1894; Anon, 1889a). Of the residuary estate of £1,277,781 9s 1d, Darbishire (1908) lists £28,028 10s 5d as being expended ‘for Openshaw baths and sundries’. The Manchester Guardian (Anon, 1890) reports that £15,500 was spent on building and equipping the baths, while William Robert Credland (1899, p 204) gives the contribution towards the library and public hall as £8,500. As these numbers do not add up to Darbishire’s figure, it is reasonable to assume that the value of the land gifted is not included in the Manchester Guardian’s figures for the baths and is potentially missing from Credland’s as well. Given that no further projects in Openshaw are mentioned in Darbishire’s account of expenditure of Whitworth’s legacy, and sums as small as £500 are itemised, it seems likely that ‘Openshaw baths and sundries’ encompasses spending on the baths, the library and public hall and the value of the land. This expenditure of £28,028 10s 5d accounts for just over two per cent of the entire residuary estate, indicating that employees of Whitworth’s Openshaw works were not a priority in the philanthropic expenditure of the legacy.

Furthermore, when we look in detail at the share buying scheme, Whitworth’s behaviour towards his employees appears rather less benevolent, which could account for the low levels of posthumous spending in Openshaw. In 1893, out of a workforce of 1,000 people, only 72 employees owned shares (Atkinson, 1996, p 298). Atkinson (1996, p 298) attributes this to their high cost – one share was equivalent to ten weeks’ wages on average – but maintains that ‘Whitworth was thoroughly genuine in his belief that “One Nation” industrial management was superior both from an employer’s point of view and from that of a workman’. But whilst Atkinson (1996, pp 296–297) characterises ‘“One Nation” industrialism’ as ‘the principle of shared management’, this characterisation is difficult to reconcile with the details he provides about how Whitworth’s shareholdings ensured that he kept ‘supreme control’ of the company. I would argue that, in fact, Whitworth’s ‘“One Nation” industrialism’ involved the granting of limited benefits, reforms and opportunities to employees in order to encourage them to feel more invested in the company and thus maintain the status quo. This revised view of Whitworth’s motives, along with the paucity of targeted charity, indicates that Whitworth’s relationship with his workers was less altruistic and more about astute business management, which is in line with the rise of business-driven capitalist philanthropy in the second half of the nineteenth century described by Cunningham (2020, p 164).

The lack of philanthropy affecting the area around Whitworth’s home ‘The Firs’ also evidences Whitworth’s philanthropic preoccupation with his intellectual community rather than a tightly defined geographical one. The partial exception to this is the cluster of buildings financed in Darley Dale. Despite his local reputation for unfriendliness (Kilburn, 1987, p 42), substantial provision was made for the education and healthcare of his neighbours and former employees through the Whitworth Institute, park and hospital in Darley Dale. There are a number of possible explanations for this. It may be that his interactions with his workers were more frequent and personal than with a large factory workforce and, along with living in close proximity to them, this may account for the different focus. Terence Kilburn (1987, pp 44–48) notes that Whitworth shaped the built environment of Darley Dale during his lifetime, for example by building cottages for his workers, and had plans for a ‘Village College’ providing ‘respectable and profitable pursuits’ for villagers, and ‘an infants, primary and comprehensive school with gardens and a playing field’ that only came to fruition in some form as the Darley Dale Whitworth Institute after his death. It is notable that the legatees were each particularly invested in certain projects and the interventions at Darley Dale were largely led by Lady Whitworth, who lived at Stancliffe Hall from her marriage in 1871 until her death in 1896 and whose continued charitable giving in the area earned her the local nickname ‘Lady Bountiful’ (Kilburn, 1987, pp 37, 43, 49–50; Anon, 1896). Perhaps Lady Whitworth’s personal interests and influence were more prominent, and less closely aligned with Joseph Whitworth’s, than those of Darbishire or Christie.

What is clear from the pattern of giving is that Whitworth was concerned with supporting causes that he had a personal connection to, whether that was the Whitworth Engineering Scholarships because of his occupation, institutions in Stockport and Manchester as the cities of his birth and business success respectively, or the bequest to an orphanage in Bristol that his infant sister was sent to on their mother’s death (Atkinson, 1996, p 1). This channelled his passion for education into largely Manchester-based philanthropy. Given that Whitworth’s personal papers were destroyed shortly after his death, it is unlikely that we can ever conclusively know the reasoning for this focus, but it fits a pattern of locally-focused philanthropy in the second half of the nineteenth century (Cunningham, 2020, pp 163–164). It might be explained by Owen’s (1964, p 164) characterisation of Victorian philanthropy as a form of civic pride and civic patriotism or Geddes Poole’s (Geddes Poole, 2014, p 11) portrayal of philanthropic culture as a display of citizenship. Alternatively, as an immensely practical man, Whitworth and his legatees may have focused on Manchester as a centre of industry and ideas where educational resources would have a sizeable impact.

Conclusion

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/211608/008By examining the effect of philanthropy on the urban environment, this article illustrates that cities can be shaped by the influence exerted by individuals as well as larger societal forces. This makes for an interesting comparison with Richard Rodger’s (2002, pp 4–12) argument that philanthropy played an important role in the development of Edinburgh’s built environment, but that this was through trusts and institutions rather than individuals, which provided continuity and restrained the ability of individuals such as politicians to enact change, and which played out through institutions’ positions as largescale landowners as opposed to the construction of institutional buildings. In contrast, this article has demonstrated that Whitworth’s specific preoccupation with education, for instance, resulted in a concentration of buildings related to learning and research on Oxford Road, which in turn attracted further educational institutions. The area’s subsequent development into the Oxford Road education corridor is now a major feature of Manchester’s cityscape. That is to say that the assistance in its early development afforded by Whitworth via his legatees represents a significant impact on the built environment – with the alignment of the majority of the funded interventions illustrating the influence of his educational agenda – and, in a larger sense, the power of wealthy individuals to sculpt the city according to their personal passions. Studying Whitworth’s philanthropy through the lens of the built environment places his intentions in sharp relief, prompting a reassessment of the benevolence – or otherwise – of his management of his company. Additionally, the emphasis on the funding of infrastructure identified by this study indicates that, in future work, such an approach has the potential to deepen our understanding of trends in charitable donations both within and beyond nineteenth-century Manchester. In providing a methodology for identifying the singular influences on Manchester’s development, this article offers the means for refocusing scholarly discourse onto individuals, in addition to social, political and economic forces.