‘South Kensington is practically as far away as Paris or Munich’: the making of industrial collections in Edinburgh, Newcastle and Birmingham

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221802

Abstract

The provocation within the heart of the Congruence Engine leads us to consider not only the connections between our industrial collections, but the differences which shine a light on the gaps that exist nationally as well as institutionally due to the unique ways in which those collections were built. Emerging out of discussions held at the project’s launch conference, this paper will compare and contrast the foundation and development of the industrial collections held within our three institutions: National Museums Scotland (NMS), Tyne & Wear Archive & Museums (TWAM) and Birmingham Museums Trust (BMT).

The dedicated industrial collections which now sit within these organisations were founded in three quite distinct contexts: the Industrial Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh in 1854, the Municipal Museum of Science and Industry in Newcastle in 1934, and Birmingham’s Museum of Science & Industry in 1951. Beyond these founding moments, their deeper roots and ongoing development have been shaped by an array of events, individuals and organisations from the local to the international, including some they hold in common and some that are unique. In charting their stories, we will explore why our collections have acquired their particular strengths and weaknesses, and the implications of this for their contributions to a distributed national collection of science and industry. This will act as the foundation for further collaborative research throughout the project as we investigate how and why particular textiles, energy and communication stories can be explored within and between our collections.

Keywords

Birmingham, collecting, collections, communications, Curating, Edinburgh, energy, history of collections, history of science, industry, museum history, museum practice, Newcastle, science, Technology, textiles

Introduction

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/This paper was inspired by discussions at the inaugural conference for the Congruence Engine project in February 2022. The aim of the project is to use digital techniques to connect industrial collections held in different organisations and locations to demonstrate the potential opportunities a nationally connected collection could bring. The authors found common ground as curators with responsibility for three of those collections and felt that, simply by bringing them together, the project had already created useful connections, before the potential of digital techniques was even bottomed out. The conversation quickly highlighted commonality in our organisational values and purpose, fellow feeling in the challenges we face as practitioners and a desire to work together within the Congruence Engine project and beyond to gain deeper insights into our similar collections in our respective organisations: National Museums Scotland, Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums, and Birmingham Museums Trust. It was agreed that it would be useful to use the opportunity of writing a collaborative paper for the Congruence Engine Special Issue of the Journal to look at the origins of the industrial collections within our organisations and investigate what informed their creation, hoping that, in the spirit of Towards a National Collection (TaNC), it would dissolve boundaries between us as curators, enable us to better understand our collections and their connections with others and, in turn, to share this with our audiences.[1]

We worked collaboratively throughout the summer of 2022, meeting regularly online to continue our discussions and consider ways in which our early thoughts could shape a useful piece of research. Individually, we embarked on deeper study of the origins of our collections, regularly coming back together to share what we had found, look for parallels and differences and talk about how our findings might illuminate wider understanding of the development of the distributed national collection. We then shared notes, passed drafts back and forth, and gradually began to draw the conclusions found here. This resulting paper, therefore, brings together three contrasting case studies: the Industrial Museum of Scotland founded in Edinburgh in 1854, the Municipal Museum of Science and Industry founded in Newcastle in 1934, and the Birmingham Museum of Science and Industry, which opened in 1951. Two of these are generally viewed as regional collections and one as national, and all were formed in different geographic regions in different periods of time. Comparing their early histories enables us to reflect on how particular contexts shaped these organisations and collections and whether those early influences have endured throughout the museums’ history.

A study of the literature suggests that our findings for our three institutional histories are broadly congruent with the early formation and evolution of science museums, particularly when it comes to the way target audiences and interpretive approaches have developed. The three founding curators had similar aims to one another, and these have been carried forward by the organisations over the decades. While they might look very different today to how they did at their foundation, they still fundamentally exist to increase understanding and science capital among the population, for all that the targeted section of the population may have changed over time. Although it may prove insightful, over a longer period of research, to conduct a much wider historical survey of technology museum collections, in the context of this Congruence Engine Special Issue this more focused study, which arose as a possibility at the project’s opening conference, does the specific work of revealing the comparability of these three museums’ collections for the conduct of the project. (For the wider picture, readers are also referred to Alberti 2022a and Butler 1992.)

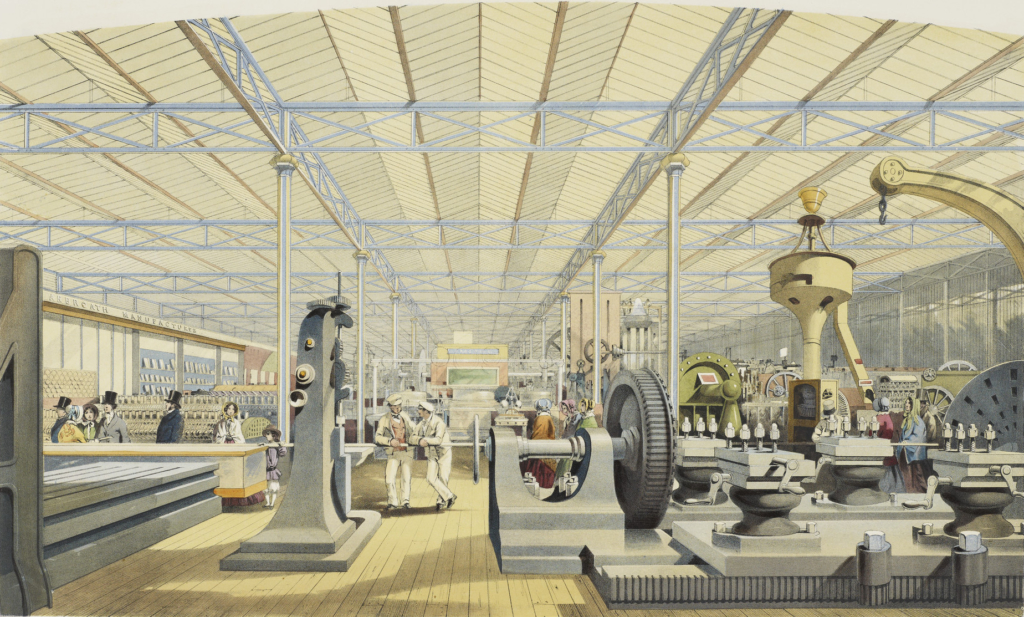

With increasing industrialisation throughout the nineteenth century governments increasingly took responsibility for education, and museums came to be viewed as one of the types of institution that could provide education for the masses (Hein, 1998, p 4). In Britain, the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nations in 1851 attracted six million visitors, many of whom were working class and travelled from far outside London through special subsidised tickets (Leapman, 2001, p 7).

The establishment of the Department of Science and Art in the wake of the Great Exhibition demonstrated the British Government’s commitment to the improvement of scientific education (Alberti, 2022a, p 45) and led directly to the foundation of the institutions that would become the Science Museum and National Museums Scotland and established an ethos that would be in part to thank for the later founding of Newcastle’s Discovery Museum and Birmingham’s Thinktank. As Stuart Davies noted, Birmingham City Art Gallery and Museum’s key benefactor – the engineering firm Tangye Brothers – wrote to the Council in 1880 in support of its creation: ‘It is all very well for critics to exclaim against Birmingham manufacturers and artizans because of their inferiority to their competitors in the matter of design, and manufacture, but what chance have they of improving in these respects? South Kensington is practically as far away as Paris or Munich…’ (Davies, 1985, p 20).

While a 2016 paper by Neta Shaby et al states, ‘whereas museums have historically been oriented primarily towards collections and research, they are now increasingly viewed by the public as institutions for public learning’ (Shaby et al, 2016, p 361), an understanding of these early years of science and technology museums shows that public learning has been one of their aims throughout their history. However, ideas about how exactly this is achieved have changed over time, as illustrated by our case studies. In the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, science and technology museums focused on using collections to demonstrate technical processes and scientific principles, and their primary intended audience was adult, albeit a range of adults from those working in industry, to academics, to a wider public who it was hoped would become more scientifically literate members of an industrialised nation. This approach can certainly be seen in the completest approach of George Wilson, the earliest of our three curators, although there had been a considerable shift by the time Swan and Bertenshaw were forming their institutions.

Anna Bunney has found that children were a significant audience for the South Kensington Museum, and later the Science Museum, from its inception, quoting an annual report from 1858: ‘In the evening, the working man comes to the South Kensington Museum accompanied by his wife and children’ and also from Building News in 1857, which said that visitor figures might be inflated as children ‘amuse themselves out of school hours by running in and out of the Museum, and putting the turnstile through more revolutions than are absolutely necessary to mark their visit’ (Bunney, 2010, p 195). While the reasons for young visitors’ presence were debated, the Science Museum formally catered to their presence in 1931 with the opening of the Children’s Gallery with its combination of working models and dioramas (Bunney, 2010, p 197). Over the subsequent decades attitudes shifted further, as summarised by Peter Morris: ‘A more fundamental change came about with the recruitment of curators with some experience of school teaching after the Second World War and the development of the Education Service from the 1950s. In the mid-1980s, to meet the challenge of the new science centres, the Museum developed the first version of its interactive gallery, Launch Pad, and the importance of children to the Museum was firmly cemented’ (Morris, 2010, p 3). Tracking our three institutions shows a similar path to that of the Science Museum in the increasing prominence given to young visitors and interactive elements within the galleries. It seems reasonable to surmise that similar developments were taking place in other established science museums at around the same time and that this had an impact on their overall approach to the display and interpretation of their collections.

A fundamental shift in the way that the three case studies present their collections is reflective of a change in the sector more broadly and in the understanding of how to foster emotional responses and connect subject matter to people and their lives, and that is through storytelling. Alberti describes how strongly his colleagues feel about this: ‘When I first arrived at National Museums Scotland, I asked the science and technology curators what we should be collecting. “Stories,” they unanimously replied’ (Alberti, 2022a, p 31). This changing approach is responsible for one of the biggest frustrations that the three authors feel with their founding curators, who focused on representing technical detail in their collections rather than documenting the human stories attached to objects and fundamental to the development of technologies. However, as we will show, what we unexpectedly found was that the early collections do reveal strong stories of locality from the very nature of what they are and what they came from, and what it was within the scope of the early curators to actually collect. They tell stories of local networks and relationships, between the curators and industry and also within industrial and scientific communities themselves.

Science, technology and industry are as relevant today as they have ever been and using the stories within collections to engage the public with contemporary issues is central to the work of many institutions. Kate Harland of West Chester Museums says: ‘in a time of climate crisis, we have the opportunity, through our museums, to reframe how people understand the background to subjects such as the Industrial Revolution’ (Stephens, 2022, pp 6–7), and Alberti (2022b) expresses a widely-held belief that ‘As trusted organisations, museums are ideal places for people to reflect on the challenges of our age, including climate change, sustainability and biodiversity loss. Museums can also address the current and historic role of science with respect to disability, inclusion, human rights and inequality.’ This unique ability must be, at least in part, due to museums’ long history of collecting, interpreting and working with the public, which means they not only have extensive catalogues of objects and research to draw on, but have mapped changing attitudes and contexts and nurtured a relationship with their audiences that allows them to host sensitive discussions that can be difficult to tackle in other fora. To remain relevant, museums must continually assess the context in which they are collecting and displaying objects and why they are doing so. While this will never cease to be a challenge, for science museums, it is one that can be traced back to their earliest days and that demonstrates that, while the world in which they operate has changed in ways that necessitate some very different approaches, their aims of education, inspiration and sharing the wonders of science, technology and industry have remained remarkably consistent.

Our three organisations are extensive and complex, with the official moments of foundation spanning almost a century, but their histories resonate with this broader historical context. Comparing key moments and personalities in their development, and their resulting impact on the collections, however, provides insight into how they were shaped by those local contexts as well as the broad national developments described above. This paper, therefore, will first explore the founding moments of each organisation in turn, to highlight the unique economic, political and museological contexts from which they emerged, before introducing their respective first curators and their backgrounds, motivations and aspirations. We then examine how these contexts shaped their early collecting before exploring the present strengths of each collection in relation to the three themes of the Congruence Engine. Through this comparison, we will seek to demonstrate that, whilst our collections are broadly reflective of the wider development of science museums in the periods in which they were founded, their particularly local contexts have nevertheless resulted in collections today which share fundamental founding aspirations yet have their own unique character. This understanding highlights their significance within the distributed national industrial collection, individually but also especially (given the aims of the Congruence Engine) together.

Foundations

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221802/002The Industrial Museum of Scotland which, over the next century and a half would evolve into the institution now known as National Museums Scotland, was established in 1854. It was founded out of the nineteenth-century interest in industry and industrial processes that was also a key factor in the organisation of the Great Exhibition of 1851 (Douglas, 1954, p 5). This interest was evident across Britain and beyond, and it is clear from contemporary press that there was a distinct push for a national museum in Scotland that would inspire innovation and educate about the geology and technology behind the rapid expansion of industry from a distinctly Scottish perspective. An 1850 article in The Scotsman detailed many of the ways in which the author felt Scotland was suffering economically due to ignorance about its natural resources:

What we have stated…is sufficient to prove the importance of a National Museum as a means for developing the intelligence, industry, and resources of the country. The waste and want which ignorance of the natural productions of the land and waters produces in many districts is very remarkable… Such ignorance is not confined to the lower or working classes, but extends to those who should be their leaders and instructors (The Scotsman, 1850, p 2).

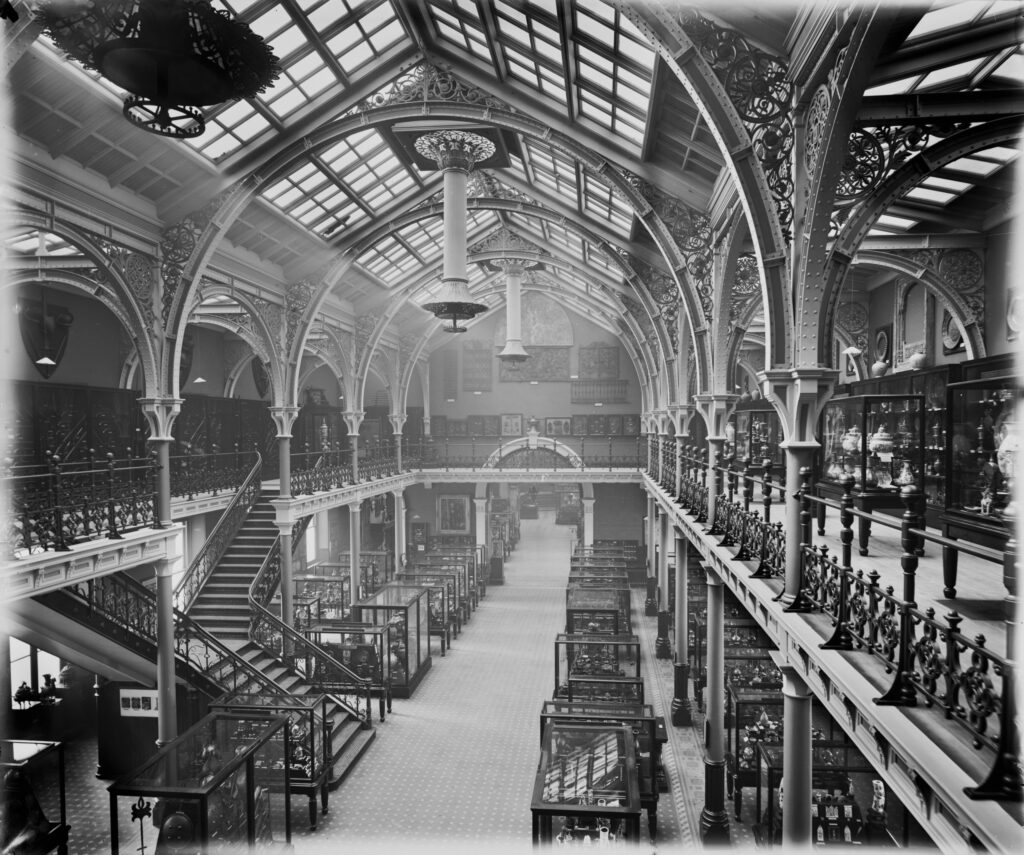

Deputations to the Chancellor of the Exchequer by various notable figures took place during 1852 and 1853 and, as a result, Dr Lyon Playfair, Joint Secretary of the Department of Science and Art, secured a sum of £7,000 from the Secretary of the Treasury for the purchase of the site and initial expenses, establishing the Industrial Museum of Scotland the following year (Douglas, 1954, p 5). The Museum was administered by the Department of Science and Art, the purpose of which was to promote education in art, science, technology and design in Britain and Ireland (The Science Museum, n.d.). A report to parliament from 1853 stated: ‘A museum presents probably the only effectual means of educating the adult who cannot be expected to go to school like the youth.’[2] The Department therefore established a number of museums during the 1850s, with the South Kensington Museum in London being the flagship and others, including the museum in Edinburgh, being branches funded by the state (Swinney, 2016, p 170). In 1855, the University of Edinburgh’s Natural History Museum was also transferred to the Department. With both collections stored in university buildings there was a grave shortage of space, and plans for a new building were soon underway. The amalgamated Edinburgh Museum of Science and Art opened in Chambers Street in 1866 (Douglas, 1954, p 8).[3]

There appears to have been no question that the museum was to be in Edinburgh. Presumably, it was seen fitting that a national museum would reflect and benefit Scotland as a whole and that it should therefore be in the capital, rather than in any of the more industrialised areas whose working life it would showcase. Despite its educational aims then, the museum’s links to the university and to scholarly life in Scotland were perhaps prioritised over accessibility for working people. In Newcastle and Birmingham, by contrast, there was no need to consider this – both were created specifically in and for the residents of their respective cities, although as in Edinburgh, as later discussion will show, this did not necessarily mean that the scope of their collecting remained quite so local.

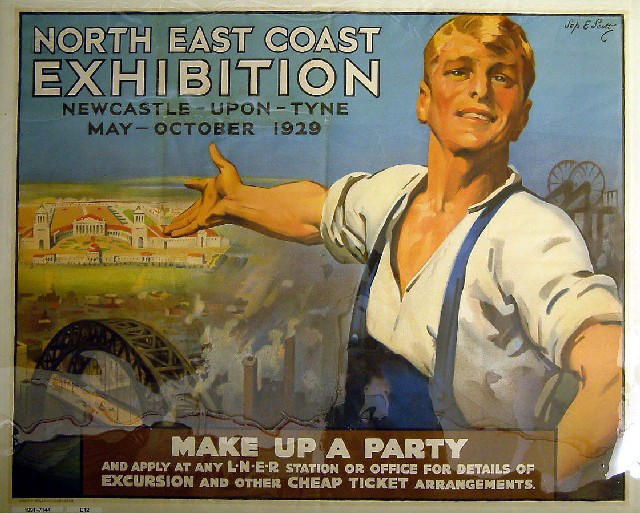

By the 1930s, economic depression was affecting the industrial output of many parts of the UK, including the traditional heavy industries of the northeast such as coal mining and ship building. Yet leisure time options were also flourishing on Tyneside as elsewhere, from cinemas and dance halls to opportunities for seaside day-tripping (Morton, 2020). It is against this backdrop that, on 20 July 1934, the Municipal Museum of Science and Industry opened its doors in Newcastle, its name apparently intentionally mirroring the National Museum of Science and Industry in London (an alternative name for the Science Museum). Indeed, several significant loans and transfers came from South Kensington to the Municipal Museum in the 1930s (Liffen, 2010, p 280).

Over four million people had attended the five-month North East Coast Exhibition of 1929, which was intended to show the rest of the country – and the world – the region’s potential for innovation and creativity, giving strength to the argument for a permanent museum of the region’s scientific and industrial excellence, past and present. Dr Wilfred Hall first conceived of the idea, and enlisted the help of Sir Charles Parsons, Professor Granville Poole, the North East Coast Institution of Engineers and Shipbuilders, and Newcastle upon Tyne City Council (Hunter, 1960). Planning for the museum took three years with local firms Vickers-Armstrongs and Parsons Marine Steam Turbine Company making annual financial contributions in the years leading up to its opening (South Shields Daily News, 1933). When it finally opened, the museum was housed in one of the pavilion buildings built for the North East Coast Exhibition on the Town Moor. A Nature review (1934, p 133) again tied the endeavour directly to the exhibition:

The ceremony was performed by Mr. R. J. Walker, President of the North East Coast Institution of Engineers and Shipbuilders, which has helped the scheme materially. The gift was accepted on behalf of the citizens by the Lord Mayor of Newcastle, Councillor J. Lead-Bitter. An institution to record and illustrate the many-sided scientific and industrial advances made in this district had long been talked of, but it was the exhibition held at Newcastle in 1929 which gave impetus to the effort which has culminated in the present Museum.

Clearly, the North East Coast Exhibition’s success – and high attendance figures – was a major driver for the scheme. However, the significant involvement of industrial figures and trade bodies alongside municipal authorities perhaps hints that some economic anxiety underpinned the desire to showcase the region’s industrial strength. Although the post-war economic context was different, by 1949 many similar tensions in Birmingham between past, present and future industry resulted in the foundation of its own Department of Science and Industry within the City Museum; the dedicated Museum of Science and Industry opened to the public in 1951. This was a period of change and uncertainty in British industry, characterised by shortages of labour and materials and yet also a profound national sense of technological futurism epitomised by the 1951 Festival of Britain (Anthony, 2010, p 109); it is perhaps unsurprising that the nation’s manufacturing powerhouse should wish to memorialise its industrial history at this moment. The origins of its collection, however, stretch back almost to the same period in which the Industrial Museum of Scotland was founded. The Arms and Armour collection was formed in the 1850s by representatives of Birmingham’s gun trade, seeking to showcase their own products and build a reference collection for their craft, and was transferred to the Art Department of the new City Museum and Art Gallery in the 1880s.[4] Birmingham industrialists were supporters and creators of the city’s collections from the beginning, with local engineering firm Tangye Brothers a major benefactor of the new City Museum and Art Gallery.[5] A few industrial objects were acquired prior to 1949, including some of the Museum’s most significant items such as the Woolrich generator and William Murdoch’s locomotive. However, these were exceptions to the overwhelming decorative arts focus, which followed the South Kensington tradition in showcasing the finest examples of craft and design from around the world as inspiration for the city’s artisan makers (Davies, 1985, p 20).

Throughout the early twentieth century local educationalists and learned societies successfully petitioned for the addition of a natural history section, and by the late-1940s there were also calls for a dedicated industrial museum for the city. Much of this local support is likely to have been influenced by the celebratory technological optimism of the Festival of Britain, with a 1950 local newspaper article indeed calling for ‘a ‘Festival of Britain’ Idea for Birmingham’ (The Birmingham Mail, 1950a, no page number).

If in Newcastle in the 1930s any underlying economic anxiety at the state of industry had only been implied amongst the Museum’s celebratory motivations, by the 1950s in Birmingham a sense of urgency to salvage and preserve was prominent. Growing interest in industrial heritage was not unique to the Midlands; technological heritage preservation movements were sweeping Britain in the same period, from agriculture to transport (Brown, 2017, pp 22–44; McWilliams, 2020, pp 253–282). However, post-war Birmingham was fertile ground for this enthusiasm, not least because it possessed so much diverse industrial heritage, and because, in the post-war economic climate, much of it was finding its way to the scrapheap. Local engineering lecturer Cyril Franklin wrote in 1945 that many machines were likely to be scrapped in the coming years as firms re-tooled after the war and urged that ‘suitable publicity requires giving to the Museum Scheme, in order to claim the co-operation of the public in acquiring relics of interest…’.[6] A 1947 meeting on the issue was convened by the Birmingham Common Good Trust and the Newcomen Society in collaboration with the Institutes of Electrical, Mechanical and Civil Engineers to identify suitable historic machinery for exhibits.[7] Political will for the foundation of a museum to house such objects was supported by a rapid surge in public and press dismay at the destruction of a number of beam engines made at Boulton and Watt’s Soho Foundry: ‘many people wrote to the city’s newspapers expressing both their alarm and their hope that more vigorous action should be taken to preserve suitable specimens.’[8] As a result, in 1949, the Museum Committee (formed of 12 members of the City Council) officially formed the Science and Industry Department.

Advocacy for the project continued once the first curator was in post. The tone of press coverage was tinged with incredulity that an industrial city such as Birmingham did not already have such a museum, and an urgency to salvage what heritage was left: ‘Now Birmingham has a very fine Art Gallery…but why no space devoted to industry? […] Birmingham has the money, it has the materials, and it has the brains to fill a gap in its culture’ (The Birmingham Mail, 1950a, no page number). That summer, the paper also reported upon a visit to the city from Torsten Althin, director of the Technical Museum of Stockholm, and his advice to the city: ‘This is about the latest minute for getting original things,’ he said, ‘… and Birmingham must start as soon as possible to save what is left’ (The Birmingham Mail, 1950b, no page number). Amongst the urgency to salvage, however, remained that thread of anxiety about the strength of British industry which was a factor in the founding of our other two case study institutions; when the City Council voted to buy the former Elkington and Company factory on Newhall Street for £118,000 as a site for Birmingham’s new Museum of Science and Industry, Councillor W Semple, opposing, remarked ‘This scheme seems rather like death-bed repentance to me’ (The Birmingham Post, 1950, no page number).

The first curators

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221802/003Our museums were led in their early years by three curators who, between them, characterised the core elements of the identity template for staff at the Science Museum in London until the mid-twentieth century: an academic, a military officer, and an engineer (Scheinfeld, 2010, pp 46–51). All were embedded in local and national scientific and industrial networks which shaped their approach to collecting and interpretation, leaving distinctive and lasting traces in the character of our collections today regardless of the variation in lengths of their tenure.

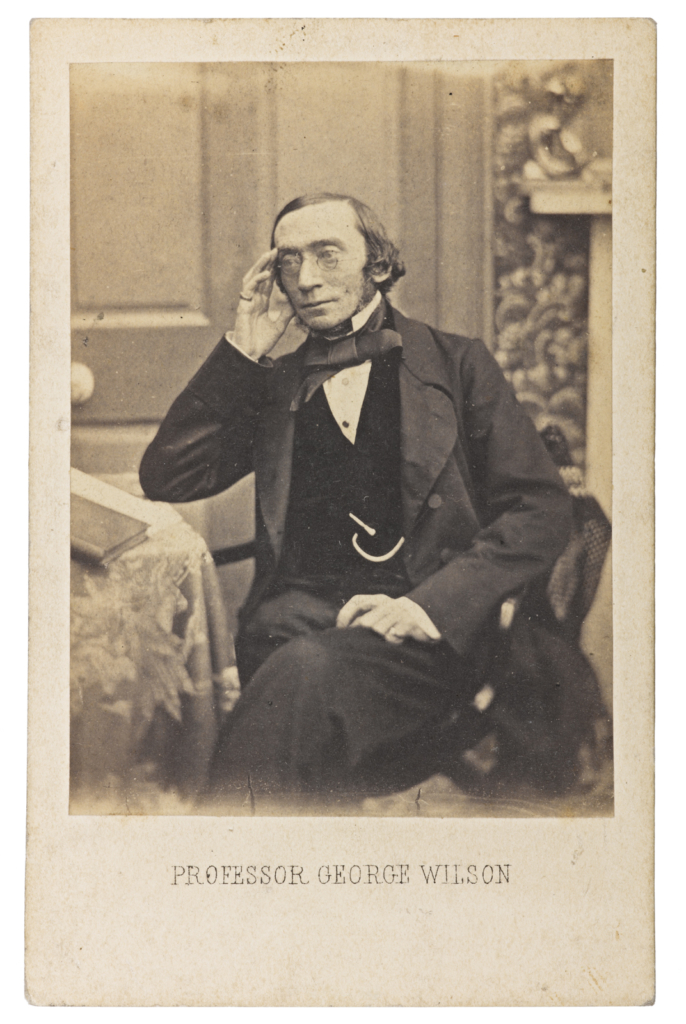

The first director of the Industrial Museum of Scotland, appointed by the Department of Science and Art in 1855, was George Wilson, who was also appointed as the first Professor of Technology at the University of Edinburgh in the same year (Staubermann and Swinney, 2016, p 22).[9] As the other staff at the time were an assistant chemist, an assistant and a porter, the director fulfilled the curatorial role (Wilson, 1855). Born in Edinburgh in 1818, Wilson was a qualified doctor but his passion was chemistry, which he lectured in at the Royal College of Surgeons in Edinburgh, the Edinburgh Veterinary College and the Edinburgh School of Art (Hartog, 1900). Although he did not live to see the Museum open to the public, Wilson’s definition of technology, his belief about the role and purpose of the Museum and his vision for how these would be realised were influential throughout the early years of the institution and beyond (Swinney, 2016, p 171).

Wilson was conscious that the collection was for the educational benefit of the public, stating that the museum was ‘intended to serve non-academic as well academic Students, and to benefit the entire community of Scotland, as well as every stranger who may enter its doors’ (Wellcome Collection, n.d., p 9). He was a strong believer in its power to educate for social change, arguing that it offered the potential ‘to increase the means of giving an industrial education to women of the poorer classes, and to multiply the vocations which may keep them from starvation, misery, and crime’ (Swinney, 2016, p 178). However, his academic role seemed prominent when developing the collection, with acquisitions fitting carefully into his teaching plans and lecture content. He was also an ambitious completist, not content with cherry-picking a few select objects as symbols of industry. His vision was that: ‘Every Industrial Art must be represented in the New Museum; that all raw materials of those Arts must be exhibited in full commercial detail, along with all the Stages through which the Materials pass before becoming finished products, besides the tools and often also the Machinery employed in working them.’[10]

Wilson died in 1859. The Industrial Museum never materialised in the format he planned, as the University’s Natural History collections, along with their curator and staff, soon also became part of the museum and there was no technological expert for some time. The collections continued to grow and were represented, when the combined museum finally opened on Chambers Street, in the Machinery Hall and the adjoining hall of Mining and Metallurgy. However, later Keeper Alexander Hutchieson (1954, p 42) felt that this lack of expertise resulted in the ‘heterogeneous nature of the material subsequently gathered into the industrial collections and the treatment of the subject of technology over the succeeding decades’. The situation did not stabilise until 1901, when Dr A Galt was appointed as Keeper of the Technological Department (Hutchieson, 1954, p 45).

It is interesting to compare Wilson’s approach, as a scientist, to creating a technological and industrial collection, with the approaches taken by the first curators in our other institutions, both of whom came from engineering backgrounds. Captain Ernest William Swan (born in the city in 1883) was the Honorary Curator of the Newcastle Museum of Science and Engineering, as it came to be known, from 1934 to 1948. The son of naval architect Henry Frederick Swan, and nephew of the shipbuilder C S Swan, founder of Swan Hunters, a prominent Tyneside shipbuilding company, Ernest was embedded from a young age within local industrial networks and followed his family into engineering. By 1901 he was manager of the gun mounting department of Armstrong Whitworth and Co., where he was responsible for the installation of armaments in numerous British and foreign battleships (Berwick Advertiser, 1936). He joined the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve (RNVR) in 1906 and saw service in the First World War, returning to duty in the Second World War shortly after his retirement as Commanding Officer of RNVR Tyne Division.[11]

According to the Museum catalogue of 1960, Captain Swan had been ‘associated with the originators and offered his services’ in the Museum’s creation (Hunter, 1960, preface). His offer was accepted, and Swan was given the task of assembling and arranging the collections with the Town Moor and Parks Committee of the Corporation. Despite the influence of the North East Coast Exhibition in setting a tone of celebration and regional pride, Swan saw the Museum’s primary function as the education of young people. As it was nearing its opening date, he remarked ‘There is still a great deal to be done but when it is opened the collection should interest everyone, young and old, and it will be of great educational value to young people and students’ (Sunday Sun, 1934, p 9). This mirrors developments in the educational emphasis of the Science Museum in London, which as noted above had been originally conceived as a museum for teachers and experts, but by the 1920s had acknowledged the importance of children in its visitor profile (Morris, 2010, p 3). Some insight into Swan’s own academic interests can be gleaned from a donation to the Museum in 2021 of his invoices from a local bookshop showing he purchased books on subjects including voyages, navigation, maritime history, British history generally, the British Red Cross, railways, farming and the British Empire. Swan died in 1948 and was replaced by Mr H W Davis – another engineer – who remained Honorary Curator until his death in 1958.

Like Swan, Norman Bertenshaw – the first Keeper of the Birmingham Museum of Science and Industry – was embedded within the industrial networks of his city. He had considerable personal interest in the history of engineering but was neither a historian nor an experienced curator but an engineer. After studying at the University of Manchester and a first role as an electrical engineer in his native Bolton, he arrived in the Midlands in 1940 to work at Chance Brothers, manufacturer of lenses and other optical technologies. His technical research there covered projects from the automatic manufacture of syringes to the production of reflective glass beads (Revill, 2002). After joining the Museum in 1950, he remained in post until retirement in 1976.

The museum – like all science museums, Bertenshaw felt – must make a positive economic contribution to society and the nation by ‘helping to break down the prejudices which impel so many teachers and parents to divert their children away from industry… [and] by providing information which will be helpful to people already in industry’ (Bertenshaw, 1964, p 68). Bertenshaw’s engineering background suited him for his appointment not just because he was interested in industrial history, but because he perceived the museum to have a vital role in supporting the city and nation’s technical future: ‘Industry is not a subject for passive study, it is the life blood of the nation’ (1964, p 68). Whilst salvaging historical items for its collection, therefore, Bertenshaw’s future focus led him to prioritise technical information in their cataloguing and display, an ethos which, thanks to the subsequent appointment of another former engineer as Curator, remained influential even after his retirement.

Although the reasons for their foundation appear at first glance to differ, from the educational reach of the state in Edinburgh to the celebration of local industry in the North East in Newcastle to the heritage preservation amidst post-war change in Birmingham, there are clear continuities between the fundamental motivation behind their foundation. That three museums founded in different places and times should have different stated priorities is not surprising, but underpinning those contexts was a common articulation of the inspirational and educational role each institution should play in support of the economic needs of the nation. Indeed, in many respects that continuity can be seen today in the contemporary STEM learning agenda, albeit through vastly different interpretive approaches. As Bertenshaw asked of readers of the Museums Journal, the question was not whether Birmingham could afford its new museum, but rather: ‘Can we afford not to have a Museum of Science and Industry?’ (1964, p 68).

Early collecting

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221802/004The three curators relied heavily on their existing academic and professional networks to begin acquiring exhibits for their institutions. Wilson gathered material from, among others, The Royal Scottish Society of Arts, The Highland and Agricultural Society of Scotland and the University of Edinburgh, which had existing collections of industrial models and scientific instruments and apparatus. A significant collection of raw material and hand tools that had been on display in the 1851 Great Exhibition also arrived, and Wilson started to bring together other technological material from across Scotland (Hutchieson, 1954, p 42). He saw his own lecturing as a driver of much of this early collecting, stating in the 1855 Annual Report:

The inaugural lecture, having excited some interest, has been published and circulated pretty widely, at the author’s expense, among those likely to become contributors to the Museum. It has led to the promise of gifts from various parties in Scotland, England and Ireland (Wilson, 1855, p 192).

Subsequent curators worked hard to build relationships with acquisition sources and, while it has not been unusual for the Museum to accept unsolicited offers, correspondence files reveal that the majority of material was identified by curators to fill gaps in the collection. A century later in Birmingham, Bertenshaw similarly made effective use of his own networks, which were within the city’s engineering and heritage communities. In 1950 the British Association for the Advancement of Science met in Birmingham and at sessions dedicated to local industrial history he was able to build upon his useful connections with fellow attendee George Cadbury, Chairman of the Birmingham Common Good Trust (Nature, 1950, pp 789–790). As the Bournville Works Magazine noted (July 1955, p 214), the Trust sponsored the purchase of objects for the new museum, and the level of collaboration between the two men was clear:

The next important acquisition was a beam engine, from Stourbridge, which came first to Bournville (via Mr. Bertenshaw’s garage), where it was put into working order before being sent to Newhall Street.

In fact, due to the initial structural unsuitability of the Elkingtons factory in Newhall Street, which had been purchased for the new museum, these relationships with local industry were critical to Bertenshaw’s longer-term collecting. As it was impossible to store many objects on site during the Museum’s development, some important pieces were promised to the collection but kept by their owners or by other Council departments until the Museum was ready to accept them – often for a considerable number of years.[12] Bertenshaw was also able to reserve many significant machines before they reached the end of their useful life, by securing agreement from their owners to affix a bronze plate to the machine in question stating it was a historically significant piece and the Museum should be contacted in the event of its falling into disuse.[13] This had the dual intention of both saving machines from accidental scrappage and encouraging its operators to better appreciate and care for it in the remaining years of its use. Jim Andrew, Bertenshaw’s successor (in post until 2003), recalled that machines with bronze plates continued to arrive until the late-1970s.[14]

In Newcastle, too, it is evident from the nature of many of the first exhibits that local collecting was an early priority. A newspaper feature (Sunday Sun, 1934, p 9) listed some of the key exhibits on display in the new museum:

At the entrance stands the first field gun built by Armstrong Whitworth Ltd. Nearby is a model of the Tyne by the Swing Bridge. By turning a handle the Bridge can be opened and closed. Workmen are now busy on a huge working model of a power station, part of the great Grid system. This is being done by the North Eastern Electric Supply Company. There are countless models of ships, among them the first iron screw collier to be built on the Tyne.

The collaboration with the North Eastern Electric Supply Company on a working model for the Museum suggests that Swan was willing to collect beyond the boundaries of ‘original’ historic objects in order to demonstrate particular stories and principles – an approach which Bertenshaw later echoed at some length in Birmingham, employing no fewer than 33 technical staff by 1955 with an extensive workshop for the restoration and production of exhibits, many of which were expected to be working.[15] In Edinburgh too, Wilson made provision for a technological workshop that was formally instituted in 1866 for making models and specimens for display (Hutchieson, 1954, p 42). The workshop continued to function until the early 1980s and models have remained a mainstay of NMS’s collecting and interpretation (Staubermann and Swinney, 2016).

The aforementioned 1934 report in Nature demonstrated in any case the extent to which Swan’s early collecting and display in Newcastle featured local industry: ‘Excellent progress has been made, in shipbuilding and electricity especially, as might be expected, but a great deal is still to be done’ (Nature, 1934, p 133). The collection grew over the next decades, with newspaper articles between 1939 and 1945 reporting on additions which demonstrate the range and geographical scope of material, from Billy, one of the first locomotives built by George Stephenson at Killingworth Colliery, to a mercury vapour pump from the USA which, despite being an excellent example of an early type, has no obvious connection to the region.

Whilst local, personal networks clearly had a major impact on the early acquisitions of all three museums, their stated geographic focus was not always so limited. Wilson had international ambitions and was of the view that to understand Scotland’s place in the world, ‘The Industrial Museum of Scotland is not intended to be a museum of Scottish Industry alone, but a Museum of the Industry of the world in special relation to Scotland’ (Wilson, 1858, p 6). A sample of the earliest objects in the Museum Register shows that Wilson was working towards these ambitions from the beginning. The first pages detail a list of fifty mineral samples from India, a selection of coal gas products from Dalkeith, which is very local to the Museum, and 21 specimens in glass vases illustrating the process of candle making from Price’s Patent Candle Company, London. In Newcastle, the focus did perhaps remain more particularly local, but there was nevertheless an acknowledgement of the widening of the geographical remit of the Museum from the beginning so that it was not actively limited to items or technologies relating to Tyneside. The author of the introduction to the 1960 Museum guidebook, Honorary Curator Mr Hunter, stated that the Museum ‘…is devoted to the history and development of Engineering Science and includes Shipbuilding, Electrical, Mining, Transport and other industries with special reference to those relating to the North East’ (Hunter, 1960, preface). As early as April 1932 the accession register shows, for example, acquisitions from organisations in London, Manchester, Glasgow, Leeds and Cardiff alongside significant donations from prominent local firms.

Despite the preservation-centric local pressure that had led to the Birmingham Museum of Science and Industry’s creation, Bertenshaw’s early collecting policy also revealed much broader ambitions than important local historical pieces alone. He seemed concerned that too narrow a focus on Birmingham industries would result in either shallow overview or unrepresentative specialism: ‘any attempt to represent a city of 1,000 trades in a Museum would be almost bound to lead from a motley collection of mediocrasies on the one hand, to a restricted group of examples representing highly technical aspects of one or two local industries on the other.’[16] In contrast to Wilson’s completist approach, however, he set out not to replicate the national overview of the Science Museum, but rather provide an inspirational and educational science museum with local character but broad scope – in the end, something more akin to the approach articulated in Newcastle.[17] Bertenshaw seemed to suggest that because it was primarily for Birmingham’s industry-rich population, the new museum had an educational duty to cast its net beyond the city’s borders. That this industrial city should have an industrial museum was undisputed, but its task was more important than local pride and nostalgia. Citing Munich’s Deutsches Museum as his prime inspiration, Bertenshaw argued:

In making this stress on local need, I do not wish to imply that we visualise merely a storehouse for old specimens of machinery made and used in the area… It is essential not only to show what one social group has achieved, but also how they benefited by the work of…others, of various nationalities….[18]

Nevertheless, the first gallery to open featured the City Arms Collection, soon followed by a display dedicated to the work of local engineering pioneers Boulton and Watt, and early collecting also focused quite strongly on rare locally important large objects. This is a natural consequence of the circumstances of the Museum’s founding; it was public concern for large and early machines which had helped spur the council to action, many were becoming available due to post-war changes in Birmingham industry, and these would provide impressive anchors around which to build its new displays. Bertenshaw appears to have made the most of the opportunity these local iconic objects offered him, admitting at the 1955 Museums Association Annual Conference: ‘To show the need for adequate premises, a number of large prime movers were reserved for exhibition. These discounted the use of several small premises which had been suggested as a museum….’[19] Historical significance, however, was not the sole or even primary element of his collecting policy, which he simply stated as: ‘Is it Good Engineering Practice?’[20] Such an approach was consistent with his aims for the Museum: to educate and inspire future engineers by the demonstration of fundamental engineering and scientific principles with high-quality objects. That many had local histories of use was inevitable given the location of the Museum and the strength of the city’s industrial heritage, but this was by no means necessary or even desirable.

Collection congruences

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221802/005The scope of this article means we cannot do justice to the full character of our institutions’ collections, each of which have long and complicated histories in which new departments for themes such as social history, science, costume, and numismatics, for example, were variously formed, amended and merged. However, an assessment of their specifically industrial collecting in relation to each of the Congruence Engine project themes – Textiles, Energy, and Communications – provides a useful spotlight on the ongoing impact of their foundational contexts. In particular it demonstrates the extent to which their localities shaped their resultant collections despite the shared broader ambitions of their founders and first curators.

All three project themes are well represented at National Museums Scotland and have identifiable roots in those first years of Wilson’s collecting. The third acquisition ever made, in 1855, was the earliest object that is now classified as Communications: a jointed submarine telegraph cable, gifted by its inventor, Maxwell Dick. Five specimens showing the construction of the Atlantic telegraph cable followed in 1857 and many more samples of telegraph cables of different types and from different locations – from the Firth of Forth to the Gulf of Persia – joined them in the following decades, with telephone cables and telephones starting to appear in the early twentieth century and the most recent additions relating to the roll out of 5G in remote rural areas.

Many of the early textile objects obtained by Wilson were samples to illustrate processes such as printing and dying, rather than textile machinery. However, in 1858 he acquired a group of specimens to illustrate Shetland wool production. By the twentieth century, most textile objects collected were machinery used to create fabrics with just occasional examples of fabrics themselves. Most of the machinery, the vast majority Scottish, came from decommissioned mills and factories and were selected as type examples rather than for their social history, a curatorial concern which came to prominence in the post-war period. The collection tracks textile production in Scotland, from a cottage industry driven by small highly skilled producers to large-scale mills that became major employers to automated textile factories.

Energy has been a key theme throughout the organisation’s collecting, but most objects acquired in Wilson’s time were coalfield geological specimens, ranging from local pits in Dalkeith to material from Pennsylvania and Assam. However, a rare 1856 collection of over 100 items including tools and clothing from Canonbie Colliery in Dumfriesshire still underpins the mining collection despite most of the objects being modest, working items in a used state. These objects still stand out today among others from this theme, but it was not then the convention to collect records about the people who used the tools or wore the various shoes among the collection. Despite illustrating a working life, the purpose of the collection was to understand the technology and the endeavour involved in mining, rather than becoming acquainted with the personalities and social history behind it; that was the work of later curatorial generations. In addition to coal objects, Wilson made a few acquisitions relating to town gas, including a model of an insulating gas condenser. Energy has remained an important collecting theme throughout the Museum’s history, including star objects such as the Boulton and Watt beam engine, and continues to grow, particularly in relation to marine energy.

Birmingham’s collection is also naturally strong in the Congruence Engine themes of Energy and Communication – both of which have major relevance to local manufacturing, but which are also represented more broadly than through Birmingham histories alone. The Technology section contains objects relating to the city’s manufacture and use of component parts for the communications industry – from Webster & Horsfall wire made for transatlantic telegraph cables, to switches and valves made at GEC Ltd. Witton, to one of the aerial horns formerly atop the city’s BT tower. Items with more national/international relevance include objects such as early versions of the speaking clock and a small but important collection of very early British business computers. Birmingham’s particular strength in diverse component part manufacturing also resulted in the acquisition of many smaller objects which, especially devoid of social historical context, can be particularly difficult for modern audiences to engage with and yet which offer huge potential to connect distributed national collections relating to the production of raw materials and finished products.

Similarly, the collection holds many objects which show Birmingham’s connections to the theme of Energy in its broadest sense, from mineshaft cables to the motor industry. Among its jewels are the nearly 200 working and preserved engines which provide a fantastic breadth and depth of coverage of their history, from eighteenth-century steam beam engines to twentieth-century aero turbofans. Many have strong local and international significance – not least the Smethwick Engine, the world’s oldest working steam engine – but there are also fine and important examples of influential types of engines from around the world. The justification for this approach was neatly summed up by Bertenshaw:

… beam engines are only part of the story. What we in Birmingham try to do is to take the beginning, middle and end of an era. In the case of steam engines we have collected rather more than we would have done if there had not been the association with James Watt.[21]

The Textiles strand of the Congruence Engine project is least represented. There are nevertheless some significant items, including a small collection of sewing machines, a Jacquard loom and a sample hank of cotton produced in Birmingham in 1741 on Lewis Paul and John Wyatt’s experimental spinning machine. Further, if the scope of the Textiles theme were broadened to encompass the clothing trade more generally, Birmingham’s vast collection of buttons and button-making machinery would be of key relevance. The three strands, therefore, demonstrate the extent to which, despite Bertenshaw’s stated approach, the local industrial context dramatically shaped the contents of the collection even as he aimed to tell far broader technological stories with that material. The collection was built with ambitions for national-level impact yet remained uniquely and intrinsically ‘Birmingham’ in character.

Finally, Discovery Museum – the present-day iteration of what began as the Municipal Museum of Science and Industry in Newcastle – was selected to lead as the Hub Museum for the Energy strand of the Congruence Engine project thanks to the particular strength of its collections in this area. The coal-mining collection currently includes over 1,100 items, including lamps, equipment, machinery and tools, surveying instruments, models and a substantial collection of archival material including plans, accounts, photographs and films. The region’s role in the development of steam turbines is also well represented, with twelve turbines and around ten models, including the four propulsion units of the steamship Turbinia and part of the 1970s C A Parsons turbine unit from Drax Power Station. The important early technical development (1884–1904) of the steam turbine by Parsons is well represented, and most of the machines are from this period although models, photographs and other records also document later progress.

The role played by Tyneside in the worldwide development of the electricity industry is covered by the electrical science and engineering collection of approximately 900 objects and 700 items of supporting archive. The body of the collection covers the important early years of the industry, focusing upon the work of the Tyneside-based electrical pioneers Joseph Swan, Charles Parsons, John Henry Holmes and Alphonse Reyrolle, as well as lighting, switches, fittings and generation equipment from a range of local and other firms. The remainder of the collection covers the broad spectrum of electrical developments ranging from engineering and transport to domestic equipment. Whilst these are the collection’s Energy strengths, it is by no means limited to these, with important collections of boilers, steam and internal combustion engines and material relating to hydraulics and wind power.

The collection covers a range of other Tyneside industries, but the themes of Communications and Textiles are not nearly so extensively represented as energy, again demonstrating the degree to which the local context shaped the character of the collection. In Newcastle, as in Birmingham and Edinburgh, even as the Museums’ curators were united in their ambition to inspire and educate the next generations of engineers and industrial workers through international stories about the broad principles of science and technology, they still set their respective institutions on a course of collecting which relied most heavily upon – and therefore most strongly reflected – the local networks in which they were embedded.

Using the three collection areas of the Congruence Engine as a lens through which to compare the collections reveals their distinct characters but recurring themes. There is surprisingly little duplication across the three, given that they were all working towards similar goals, and this is reflective of different approaches and local influences. Understanding all three collections gives new perspectives and insights to each individually and reveals ways in which the collections support and complement each other. While it is unlikely that their founders would have seen it this way, it is clear from this study that these three museums form important components of a distributed national collection and, while each is strong and significant in insolation, together they are far greater than the sum of their parts. It is these factors that make them of particular value to the Congruence Engine project.

Conclusion

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221802/006When we began discussing our respective collections, we felt instinctively that they had many similar characteristics and so we wanted to explore the implications of this for any future collaborative research during the project, and also for the concept of a distributed national collection more broadly. This short study of the museums’ founding moments, first curators and early collecting has gone on to reveal several similarities and differences, some of which we predicted while others we did not. Further, whilst we felt there to be an intrinsic value in each of us deepening our understanding of the character of our collections and institutions, we have also found through their comparison a number of intriguing themes which hint at implications for our understanding of the history of science and technical museums in Britain more broadly. The nature of the Congruence Engine afforded us a valuable opportunity to conduct new archival research into our collections’ histories in this collaborative way – suggesting, perhaps, the project’s potential in helping to move beyond disconnected institutional histories or the dominance of a handful of larger institutions in the national story of museums of science and industry.

The founding moments of the three museums occurred at very different times over the span of a century which saw huge political and economic changes nationally and internationally, not least two world wars. The ways in which science, technology and industrial collections were defined naturally also changed within that context, and each of the curators and institutions had slightly different ideas about this which are reflected in the nature of the collections today and which broadly follow the pattern of development of science museums outlined in the existing literature. Two key themes emerged throughout our comparisons: first, the similarity of purpose articulated by our predecessors despite the variation in geography and time in which they were operating; second, the degree to which that local context nevertheless went on to shape the collections despite their similarly stated broader ambitions. Finally, the emergence of these themes across our collections has highlighted to us the surprising continuities we share with our predecessors and the extent to which the foundations they laid support our current and future ambitions far more than we previously realised or appreciated.

To address first the similarities between the three curators’ perception of the purpose of the collections they were building: it has been particularly interesting through our collaborative research to have come to a far more nuanced understanding of the particular motivations which lay behind what and how they collected. A commonality we shared at the outset (which is doubtless far from limited to the three of us) was our initial frustration with our predecessors for their overwhelming focus on technical detail in the objects’ documentation to the almost complete exclusion of the personal and community-focused stories which we now most wish to tell. That all three curators saw value in historical objects is evident from the efforts they went to in their careers to preserve them. Wilson, for example, was a completist, aiming to gather examples of every type to build up a complete historical record of an object category, whereas Bertenshaw, working a century later, wished to focus only on those objects which demonstrated the pinnacle of his subjective understanding of ‘good engineering’ through time. If the methods of the three curators differed, though, their motivations were remarkably consistent despite the variations in location and time in which they were working. The details they chose to record about the historical objects they acquired was overwhelmingly technical not simply because they were all scientists and engineers rather than historians, but because the value they saw in the preservation of historic objects lay primarily in their ability to further contemporary technical education. The foundation stories are therefore naturally products of their time and of the personalities involved but are all underpinned by similar beliefs in the importance of technical education to the economic wellbeing of the region and nation.

This shared motivation led all three curators towards a more national and even international focus, even if they acknowledged to varying degrees that their collections would have a particular local character. To address the second theme therefore: we all knew that our collections contained a combination of some local and some more national/international objects and stories, but we expected there to be far more duplication than we found. Whilst there are crossovers – and of course some archetypal objects in common, from beam engines to transatlantic cables – contrasting our collections through the lens of the Congruence Engine themes revealed that they have been fundamentally shaped by their local industrial contexts to a greater extent than any of us expected. National Museums Scotland (as the only national amongst us) unsurprisingly covers all three themes the most comprehensively, whilst Birmingham’s collection best reflects the city’s manufacturing strength in Energy and Communications, and Newcastle’s is extraordinarily strong in Energy thanks to the city’s role in the turbine and electricity industries with consequent under-representation for the Communications and Textile strands.

Although the three first curators all essentially aimed to represent similar themes in their collections, therefore, they, and their successors, worked with local networks and companies, building relationships that have resulted in collections with distinct characters and strengths in different areas. The local contexts in which they worked resulted in collections that today are far more regional in character than they ever intended. A promising potential avenue for further research might be the further investigation across a broader range of institutions, even – or perhaps especially – those such as the Science Museum which have a more explicitly national focus, of the extent and manner in which local social, educational and industrial networks formed and shaped the development of Britain’s industrial collections. It is here too that the digital tools being tested within the Congruence Engine project might also prove valuable, in uncovering and mapping those networks and their links to collections.

To conclude, we wanted briefly to reflect on the implications of these discoveries for our work today, for our future collaboration as part of the Congruence Engine project amidst the wider concept of a distributed national industrial collection, and for our broader understanding of the history of science and industrial collections in Britain. Each of the original collections has, either from its foundation or at some stage in its history, become a part of a larger, multi-disciplinary institution and this has also had an impact on how the collections are defined and viewed by staff and external parties. The relationships of the science, technology and industry collections in National Museums Scotland, Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums, and Birmingham Museums Trust to the collections held by other departments within those organisations could be the subject of a whole other paper, but discussions during the course of our research have revealed that they are all, at best, complex. Despite this, we have found that the evolution of the three museums and collections is generally reflective of developments within science museums broadly, particularly in relation to their interpretive approaches.

Underlying those sector developments, however, we have been surprised to see that the articulated purpose of industrial collections has remained remarkably consistent, even between the 1850s and today. Although it is far from our only social purpose, one of our core roles now, as it was for our predecessors, is to inspire and facilitate the development of what we might now term ‘science capital’ amongst our visitors.[22] This is by no means intended to suggest that industrial museums have remained static for 170 years. As noted, there have been dramatic shifts across that period in what we collect, what stories we record about those objects and, especially in recent years, the way we work with individuals and communities to tell those stories with more critical engagement and social purpose. Nevertheless, we have found it interesting to imagine that, if our predecessors were able to assess our work today, they might be surprised by some of our methods and target audiences but would recognise some core shared values underpinning what we do.

In all three institutions, as in the sector more broadly, we see a shift towards social historical stories focusing on local people’s experiences of, and contributions to, industry past and present. There is much research to be done in collaboration with our communities to uncover the social histories hidden within the technical objects in our collections. Yet, where previously we may have felt frustrated by the challenges caused by their existing lack of social historical context, it has been refreshing and reassuring to uncover the extent to which the collections are fundamentally reflective of the places in which they were built. We have inherited, therefore, collections which are uniquely placed to support our increasingly ‘locally framed’ interpretive approaches.

Finally, we feel that this brief and by no means comprehensive comparison of our collections’ early histories has demonstrated in a focused way some of the strengths within the distributed national industrial collection. Where we expected significant duplication, we have found surprising variation. As the project develops, we hope to return to our institutional comparisons in a more targeted manner in order to explore how specific themes within the project’s energy strand, such as mining, have been represented respectively, and therefore the cross-collection research questions that, together, we have the potential to support. This brief overview of our collections as a whole, however, has demonstrated the potential impact of the experiments being undertaken as part of the Congruence Engine project into both the digital tools and ‘hand-stitching’ processes which can draw out their connections. If the patterns which have emerged in this comparison of our collections turn out to be reflective of science and industry museums more broadly, then the value that can be gained by working towards a national collection becomes even more apparent, with the discontinuities turning out to be quite as informative as the connections we make. Further research as the project develops may begin to explore whether there are certain stories which are only uncoverable through a distributed national collection.