Review: Colour Revolution: Victorian Art, Fashion & Design, Ashmolean Museum Oxford exhibition

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/242101

Keywords

art, colour, colour revolution, design, exhibitions, fashion, science, Victorian

If your image of Victorian Britain is a gloomy grey place, the Ashmolean Museum’s exhibition Colour Revolution: Victorian Art, Fashion & Design in Oxford (21 September 2023–18 February 2024) would make you think again. As the title suggests, this ambitious and vast subject was investigated through art and culture with a range of weird, wonderful and colourful art and artefacts from the Museum’s own collection combined with loans from more than thirty institutions. It featured artists, writers and performers as well as scientists as the titular colourful revolution was also a scientific one, part of the Industrial Revolution and its social and cultural transformations. In this way, the exhibition placed science and technology’s role front and centre allowing interdisciplinary connections and foregrounding how science and industry have been embedded in culture, commerce and mass production.

The curators made their intention to challenge the assumption about a monochromatic Victorian Britain clear by bringing the visitor face to face with it from the start. As the visitor stepped into the dimly lit lobby of the exhibition they were greeted by a blown-up print of one of Gustave Dore’s Dickensian-like images of nineteenth century London with its slums and smog. Opposite, Queen Victoria’s imposing and era-defining black mourning dress was on display, the first of many show-stopping objects to follow.

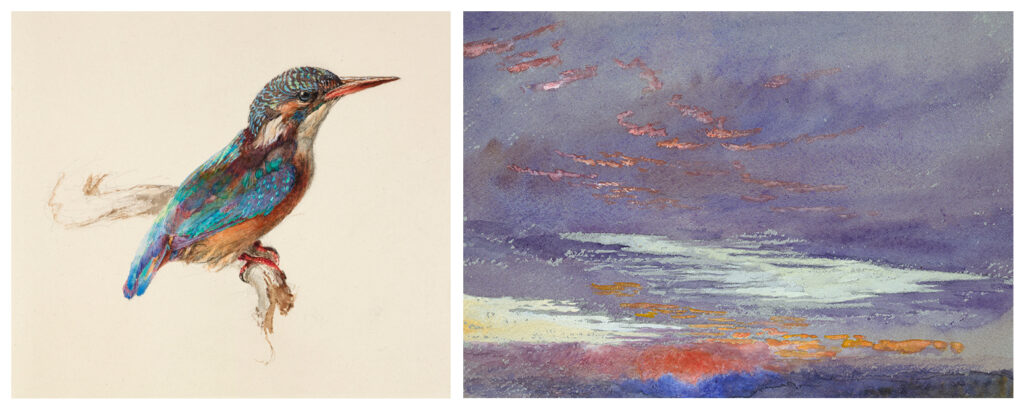

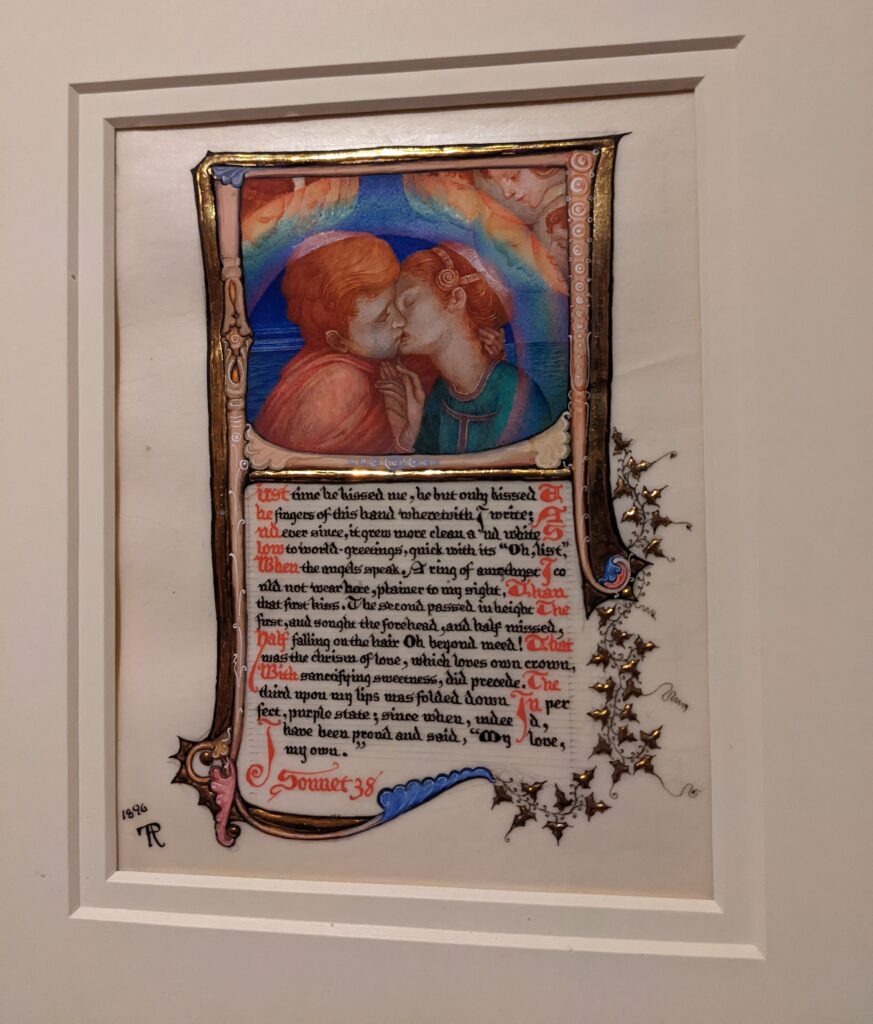

After this theatrical entrance, colour’s importance for the Victorians was introduced via the most influential art critic and thinker of the time, John Ruskin. Ruskin was the first Slade Professor of Fine Art at the University of Oxford, and he advocated the use of colour inspired by nature in his truth-seeking mission through art. This approach was shown by three beautiful watercolours on display side by side: two studies by Ruskin showed a vibrantly coloured kingfisher and dreamy purple clouds at dawn next to a painstakingly detailed gentian flower in ‘ineffable azure’ by Ruskin’s disciple John Brett. Ruskin also championed many British artists including the Pre-Raphaelites and most notably J M W Turner who he defended as the greatest colourist. Turner’s shimmering ‘Venice, from the porch of Madonna de la Salute’ on loan from New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and the lush red in John Everett Millais’ ‘The Woodman’s Daughter’ bore testament to both artists’ exceptional manipulation of colour. The latter painting, inspired by a medieval English poem, was part of the Victorians’ exploration of colour’s usage in their own past, dispelling the myth of the ‘Dark Ages’ as devoid of colour. Jane Morris’s embroidered wall hanging and Phoebe Anna Traquair’s illustration for Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s love sonnets were shown along with the medieval illuminated manuscripts that directly inspired them, and provided examples of how that ‘sacred’ study of medieval colour found outputs in different media.

In contrast to the ‘sacred’ understanding of colour by Ruskin and the Pre-Raphaelites, the experiments of Victorian design reformers were shaped by scientific principles and particularly the growth of the natural sciences. A beetle vase by the reformist designer Christopher Dresser is a case in point. Although its bold colours are not realistic, they drew attention to the insect’s morphology being studied at the time by scientists under the microscope. The defining scientific theory about colour in the natural world was the most controversial. Charles Darwin’s evolutionary explanation of, for example, the role of iridescent feathers in sexual selection created heated debates about science demystifying nature, formed ideas of beauty and fuelled fashion crazes with destructive environmental effects. This was evidenced in the exhibition by a peculiar necklace made from decapitated heads of seven emerald and ruby topaz hummingbirds, nature’s most colourful animal according to the Victorians.

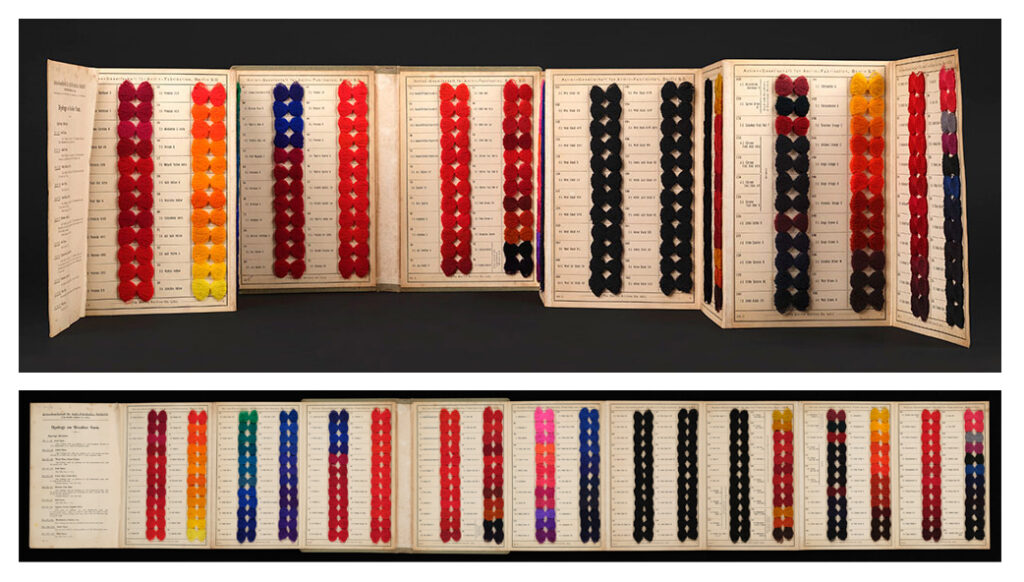

It was in the next section, halfway through the exhibition, that the impact of science became explicit. In 1856, William Henry Perkin, a student at the Royal College of Chemists, accidentally produced a purple dye from coal tar while trying to synthesise quinine for malaria treatment by isolating aniline salts. Two cases styled as shop windows included British and French aniline dyed garments, undergarments, shoes and German synthetic dye samples in myriad shades indicating the explosion of colour in Victorian wardrobes that the commercial application of Perkin’s discovery allowed. They also referenced the synthetic dyes’ development in Europe with Germany and Switzerland becoming the leading manufacturers by the end of the nineteenth century. Perkin’s ‘mauvine’, as it came to be called, made colour accessible to the masses, until then a luxury only for the wealthy few. Given the industrial revolution’s substantial social changes, I would have liked to see the class implications of the Colour Revolution explored further.

The Victorians’ fascination with the new colour possibilities went hand-in-hand with their perception of British white superiority as expressed in the colourful spectacle of the International Exhibition of 1862. Included in the Exhibition as an abolitionist work, John Bell’s sculpture ‘A Daughter of Eve: A Scene on the shore of the Atlantic’ employed the new colour technology of electrotyping, applying a bronze patina to copper, to depict the skin of a bare-breasted unidentified enslaved African woman. Displayed in this exhibition, the sculpture served as a material manifestation of the disturbing Victorian ideas that connected colour with race. It also highlights science and industry’s entanglements with enslavement and empire whose legacies still shape museum collections and contemporary debates. In the exhibition’s catalogue the curators commented on the calculated decision to include such a work as ‘an opportunity to think about race and gender and its expression in Victorian art’. But what about Black Victorian artists and their relation to the Colour Revolution? What about positive representations of people of colour in Victorian culture?

When it comes to the Victorian fantasy of a regressive ‘Orient’, a series of works by artists-travellers in search of the Middle East’s sense of colour and light were represented in the next section but it was another sculpture that, for me, captured colonial hierarchies of power and their colour associations. Maharajah Duleep Singh was the last maharajah of Punjab, exiled to Britain after the British annexation of Punjab in 1849. Sculptor Baron Carlo Marochetti, who was commissioned by Queen Victoria to make Singh’s bust for his birthday, chose watercolours for a realistic depiction of his skin tone and colourful attire, an ‘orientalist’ royal signifier. The piece was highly debated among the court for its use of colour and Marochetti had to replace it with a white marble version upon a request from the Queen.

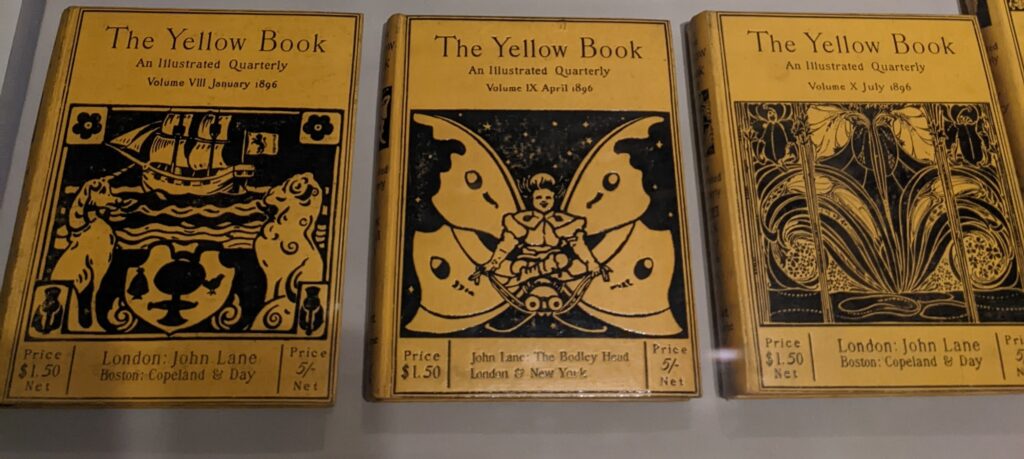

In the final section the tone of the exhibition changed, moving on to colour for colour’s sake as embraced by the Aesthetic and Decadent movements from the 1870s onwards. Oscar Wilde’s quote on the wall that read ‘Mere colour, unspoiled by meaning, and unallied with definite form, can speak to the soul in a thousand different ways’ expressed this sensory approach to colour and its undertones of queerness, subversiveness and cosmopolitanism. Focusing on certain colours and their late Victorian meanings worked well here. Yellow and green were the main colours that carried such connotations and dominated the palette of the fin de siècle avant-garde. Combined in Ramon Casa’s painting ‘Decadent Young Woman After the Dance’, an elegant Parisian woman lies exhausted on a green sofa with a yellow book at hand alluding to the yellow covers of French illicit novels. In Britain, this stylish and underground spirit was encapsulated by the periodical Yellow Book. Its yellow covers illustrated by Aubrey Beardsley’s vision of decadent femininity, also apparent in advertisements and posters, defined the so-called ‘Yellow Nineties’. Blue was used as a metaphor for male homosexuality in the cover of a rare copy of the In the Key of Blue book, the result of a collaboration between queer artists John Addington Symonds and Charles Ricketts.

The exhibition closed with examples by two pioneer women artists who used light and colour in novel ways making the most of the new technological advancements in photography, film and electricity. It was mesmerising to watch a film where contemporary dance choreographer Jodie Sperling was performing the work of early dance pioneer Marie Louise Fuller (also called Loie), although it would have been even more enjoyable if presented in a dedicated room with seating. Fuller, who initially performed her ‘Serpentine Dance’ at the famous Parisian cabaret Folies Bergère in 1892, turned her body into a swirling light and colour spectacle with the use of voluminous white silk costumes and complex electric lighting systems that she patented herself and which earned her the nickname ‘Electric Fairy’. Finally, in presenting the pioneering colour photography work of Sarah Angelina Acland, who was an Oxford resident and Ruskin’s student, the show came full circle to its start with a curatorial narrative of art and science in dialogue.

Although the more complex aspects of Victorian realities around class, gender, sexuality and colonialism were not approached head on, they were acknowledged consistently throughout the exhibition. At times, there seemed to be an assumption of audiences’ prior knowledge of the period’s context which is a challenge for any thematic exhibition with a broad chronological remit. In terms of a more accessible visitor experience, different design choices such as more available seating would have helped. Nevertheless, Colour Revolution succeeded in challenging assumptions of Victorian culture. At its strongest, it used colour to highlight collaboration, experimentation and innovation across art, science and industry that shaped an era with lasting impact in our modern world. With a combination of stunning artworks by household names like Turner, Millais and Whistler and lesser-known artists such as Anna Atkins and Sarah Acland with strong decorative works and fashion pieces, the exhibition was a feast for the eyes and mind and made for a very enjoyable afternoon in Oxford.