Collaborative conversation as a method for exploring multiple perspectives on ‘community’ and forms of knowledge in the Congruence Engine

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221809

Keywords

Community Engagement, conversational writing, digital sustainability, knowledge co-creation, online cultures, participatory heritage practices, remixing

Introduction

This collaborative conversation is the result of a group endeavour to discuss some of the initial experiences we have had as we develop common approaches to working together in the Congruence Engine project. We convened as a small group who were interested in exploring new forms of community engagement and knowledge co-creation. Each of us has particular interests, experiences and expertise that we feel complement, challenge and encourage open discussion.

Simon is Co-investigator in the project, responsible for digital translation of archival resources for community partners. His research is focused on the role of the archive and the use of digital tools in storytelling and the voicing of community histories. Stefania is the Research Fellow involved in the textile investigation. Her research explores the role of sound culture in the digital transformation of museums, with new forms of heritage, curatorial practices and ways of engaging communities. Arran, also Research Fellow in Congruence Engine, is co-facilitating the action-research methodology. He is interested in museum collections, digital practices and online remix cultures. Maggie is trustee for Saltaire World Heritage Education Association, one of the project partners. In the past years she has been managing the Saltaire Collection, researching, and writing books, articles and oral histories. Stuart is Programme Coordinator for Wikimedia UK, also partner in the project. He has eight years’ experience as practitioner in digital heritage, collaborative knowledge creation and open data.

Our conversations flowed quite naturally; we could have continued for hours, using ‘intense (and perhaps endless) conversation’ as a method to ‘discover underlying values, interests, and conflicts that are not immediately understandable or are taken for granted’ (Ripamonti et al, 2016).

As we wanted to explore themes freely, we did not set initial boundaries, allowing topics to evolve and spill over into new areas. We wanted this collaborative conversation to reflect the very essence of the project – a space in which discussions and opportunities are able to present themselves in an emergent way, develop where and with whom they resonate, and fizzle out, leaving space to follow new avenues, where appropriate. We were not sure how the process would work, or if it would even sustain the time we had allowed for each session. We needn’t have worried – and what we present here is a distillation of a lively, engaged and ongoing conversation that demonstrates some of the many perspectives in the project and invites widening perspectives and ongoing continuation.

In our choice of format, we are indebted to an autoethnographic essay written by Marcin Kafar and Carolyn Ellis (Kafar and Ellis, 2014). Their conversational approach seemed like an appropriate model for capturing the core elements of our conversation and in allowing a polyvocal approach to be registered without an over-arching editorial ‘voice’, as well as aligning us with an approach that values personal lived experience as a valid research insight.[1] There are limitations to our emergent conversational approach, and we felt more structure was necessary. We introduced this, but in an open and consensual manner. We each amended and tidied up the transcripts of our own comments and jointly edited the final selection, annotating and expanding via footnotes to add more nuanced and expansive references and resources.

Conversational frames

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221809/001As we talked, our discussions coalesced around a series of topics that felt central to developing an understanding of who we were, how we wanted to work and what seemed most important in relation to the development of the project and the focus of our research and practices. Our reflections converged around four main areas: the meaning we give to ‘community’ and the nature of these relationships; the modes and spaces for engagement; the different types of knowledge emerging from these interactions; and finally a series of practical issues and challenges that can act as potential barriers. We have used these four main topics to structure the article, expanding our discussion via footnotes to add a further level of reflection and contextual information.

1. Reflecting on the word ‘community’

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221809/002We began by considering how we might think about the people and groups we are working with and how we ‘frame’ our partners and audiences. The frameworks we use and language that supports them is potentially problematic and enforces notions of authority or status within a project and more broadly. We felt it important to begin by acknowledging the importance of language and the need to think about mutually understood terms and meanings.

Stefania

Let’s start from the word ‘community’. What do we mean by that? It might be useful to share examples, from our own practice, of different types of participants and different ways to interact with data.

Simon

Quite often they see themselves as individuals with their own projects. Citizens is another word, but I find it equally problematic. And ‘audiences’ implies a receptive mode, doesn’t it?[2]

Stuart

In Wikipedia, we have affiliates around the world and those can be small user groups. But they might not see themselves as a community, so we’re just imposing this term on them and saying, ‘You’re a community’.

Arran

This is why, in the Congruence Engine project, I have been trying to avoid the use of the word ‘community’. We can talk about people who are in the project, and the people who are yet to be in the project, and that could be the differentiation we make. I suppose I’m interested in us not replicating the idea of: we are the researchers, you’re the community, and we are going to extract knowledge from you in order to help us develop the project (Facer and Enright, 2016).[3]

Stefania

I think we are searching for a different meaning here. In the Museums of the Dolomites project, we didn’t engage a pre-existing group (For more information on the project and its impact, see Zardini Lacedelli et al, forthcoming 2023).[4] We created a heritage community[5] with a shared interest in the Dolomites. We worked with people with different interests, forms of knowledge and expertise: residents, cultural professionals, researchers, amateurs, Dolomites lovers. We used the word ‘community’ to describe the group of people that the project was able to create.

Stuart

This is similar to the Wikipedia model. Sometimes there is a pre-existing group, sometimes not, but Wikipedia creates its own knowledge communities from individuals. As long you are producing knowledge, you are part of it.[6]

Arran

There is something in human nature about that, isn’t there? It’s not just the digital affordance of tools and platforms or something that only happens for physical heritage. There’s something about working as a group of people with shared interests to protect something that’s important to you. And this is something I came across a lot in my PhD research, when I looked at online cultures and these forms of communities that develop around niche areas (See Phillips and Milner, 2017; Milligan, 2017; Rees, 2021).[7]

Simon

This idea of online communities is really interesting. The fact is that, online and on social media, people aggregate around particular histories, particular themes (Duffy and Popple, 2017).[8]

Arran

Yes, totally, and not just online and with social media. The history of Saltaire could be seen as a niche area to some. The Saltaire collection was developed from people who have got this interest that might be considered niche in the grand scheme of things but are now a core node in linking to other national heritage collections.

Maggie

And this is one of our major advantages. The Saltaire Collection is a tiny resource compared to a large museum collection, but we are lucky to have volunteers who come along and want to do research.[9] They may not have an academic research background in some cases but enjoy focusing on an aspect of Saltaire’s heritage and want to add to what is known. You cannot actually expect to do that in a big museum, where you’ve got lots of galleries to look after and your focus is on attracting many visitors.

Stefania

Maybe this is the way of framing the concept of ‘community’ in Congruence Engine. We are gathering people interested in the textile industrial history from different angles, without a pre-established idea of what their interest might be. They might come from a traditional academic background; they might be interested in their family history; they might want to engage in different types of history we cannot even imagine. But in the end, we will create a group of people that we can define as community: the community of Congruence Engine.

Simon

The thing that interests me is what is people’s incentive and why do they want to do something? And also what do they get out of it? In the project we talked about distributed collections a lot. Perhaps we also need to talk about distributed communities. Because they’re not a homogeneous thing. They have different motivations, different desires, different rewards from working as well.

Stuart

And there might also be different levels of engagement. In Wikipedia, the more work you do, the more you are involved in the project. Some people can become more prominent because they might have more time and resources, but also because they are just more driven to contribute than others. This can affect decision-making within the project as an in-group is formed, and a record of significant contribution can afford individuals licence for bullying or controlling behaviour.

2. Where and how do we co-create knowledge

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221809/003Following our consideration of the types of people and groups we work with and how we tend to categorise them, we moved on to think about the importance of recognising where knowledge resides and how we can co-opt and value it. The role played by all who make up the Congruence Engine and are involved in the co-production of knowledge is paramount. As such we also thought about the ways in which we engage – from ‘institution’ outwards, and from ‘community’ inwards.

In opening up this question and considering what motivates people we thought about the dichotomy between spontaneous contributions versus outreach work – trying to recognise the two-way flow of knowledge production.

Stefania

Talking about the different motivations in contributing made me think of the different ways in which we can promote these forms of knowledge co-creation. Are these individual contributions spontaneously shared or proactively stimulated?

Maggie

We are fortunate in the people that we attract come because they want to write and share. Amongst our volunteers are a group of people who primarily want to research and write. There are six or seven of them, and we have named them ‘The Writers group’. And that’s a typical scenario for our small collection to have half a dozen people who are interested in pursuing enquiries.[10]

Stefania

Stuart, what is your experience? Do people just want to contribute to Wikipedia or do you actively engage with individuals and groups?

Stuart

Generally people come to us, but it depends. There might be a self-selecting community of people who want to contribute with their knowledge. But outreach is always a thing that we try to do actively. I was talking to a guy the other day who runs a young historians project, which is documenting the work of black people in the NHS. This is an important area of British history which is usually under-documented. So, I am going to that person asking, “Your group is doing a good work in this area, is there any way we can work together to somehow get some of this content on to Wikipedia?”

Stefania

Would you say that the local history type of knowledge is more self-selecting or needs more outreach?

Stuart

It’s hard to say. Local history is kind of self-selecting because it is the person that wanders around [their] town, goes to the archives, writes things down and puts it on a WordPress blog. But in order for that to interface successfully with a Wikimedia project, we have to facilitate their involvement. In general, any organisation, any group that’s got access to any slightly more formal ways to publish that go through an editorial process, then that starts to look like a source appropriate for Wikipedia and we can start extracting encyclopaedic information from it. University or institutional blogs are quite useful, for example, as places where academics can write about a subject in brief, perhaps to update research findings or add to the current thinking on something.[11]

As Stuart notes here, the real challenge is how to make existing knowledge more visible, stable and sustainable. So much is lost or hidden and falls through the cracks before it can be recognised and made widely accessible.

Simon

The question is: how do we make this kind of material and knowledge that we could find in a blog more stable, more visible? I did a project with a local history organisation in South Yorkshire. They were funded 15–20 years ago by the Heritage Lottery Fund, which was building regional local history websites.[12] There were several groups and affiliations of local history organisations who had put up all their collections on a big web platform. But then the company went bust and all data was ’lost’ with regard to this central resource. When I asked, “Where is all your data?” they showed me an ancient laptop and said “It’s all on here.” So, we worked with them to help get it onto the cloud. There is a lot of rescue work in what we do.[13]

Stefania

The concept of ‘rescuing’ perfectly captures the experience I had in the Museums of the Dolomites project. In 2020 and 2021, we ran a social media campaign asking people to share their memories on places, rituals, traditions, trails, sport. We noticed that local residents and Dolomites lovers were already sharing their knowledge and experience of different aspects related to the nature, history and social life on social media. So we created a series of ‘prompts’, inviting users to share memories through their profile using the hashtag #DolomitesMuseum.[14] Through the hashtag search, we then collected all the social media posts which were created in response, and we transferred this knowledge to a shared digital space curated by the museums of the project. We realised that social media can be a powerful source to collect but can also prompt the sharing of knowledge, memories and stories around a place.

Arran

I think it’s really interesting because a lot of people still see social media as a very transient thing, despite it not really being transient. It is true that anything on social media can be deleted, but so can anything else online. Even if something is later deleted, if it has gone publicly online it is possible that it may have also been archived before it’s deleted (See Jules et al, 2018).[15] Stuart, you were mentioning blogs before. Would you say that a social media post would be a valid enough source of information for some knowledge to be published on Wikipedia?

Stuart

As a rule, Wikipedia doesn’t accept self-published sources. Sometimes social media is used as a primary source on certain articles on Wikipedia, for example about social media subjects themselves such as a notable YouTuber. But there are definitely issues with the sorts of knowledge that Wikipedia privileges. Part of my work is translating knowledge or getting something to a state where it can be represented on English Wikipedia, even in the tiniest form, because often you’re just looking for the smallest fact from a large amount of information to supplement or balance something or just keep a subject up to date.[16]

Maggie

This is an issue we have. I don’t think that Saltaire Collection has ever considered publishing the outcomes of this research work beyond our own website. We’ve never gone beyond our own website, in terms of sharing. But I’m really interested in the possibilities of being connected to Wikipedia.[17]

3. Exploring new forms of knowledge

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221809/004Our conversations revealed that we were all interested in the nature and value of different types of knowledge – some institutional and formalised – others open and unstructured that define ‘communities’ and our potential interactions between them. In some respects, we felt that they might be seen as in conflict or oppositional – and that they might be perceived as existing at different levels of value and intellectual worth. At the heart of this lies an issue of power and relative authority that also emerges later in discussions of the status of storytelling versus archival records and whose interpretations are the most ‘valid’?

Our first exchanges considered the proposition of academic versus non-academic knowledge and the issue of power.

Stefania

These forms of non-academic knowledge are really interesting for us to explore. In this kind of participatory heritage project, different levels of expertise and new forms of knowledge are shared and created alongside the more traditional curatorial contributions. In the Museums of the Dolomites project, some of the museum curators felt uncomfortable with the different forms of non-academic knowledge which were being shared in the digital space (See also Zardini Lacedelli et al, forthcoming 2023).[18]

Simon

That’s why I raised the idea of folk history because there is that sense that there are different types of histories or different types of stories that have different status. Sometimes they bleed into each other and it becomes very complicated, but that’s the way people talk and think. So, it’s messy, which I really like, but it upsets ‘proper’ historians.[19]

Arran

There is a question of power here, isn’t there? The idea that someone’s knowledge is not valid until someone else in a higher position of power has said it can be valid. Even classifying a community story as community knowledge is an ‘othering’. It is a great thing that the museums are welcoming in more personal and community-derived stories, but it’s still differentiating between curatorial and community knowledge (Macdonald, 1998; Mason et al, 2018; Dewdney et al, 2013).[20]

Stefania

This reminds me the conversation I had with the Science Museum Group team about the different spaces for the creation of digital narratives. They described the blog as a dynamic polyvocal space where everyone can contribute, and the ‘Objects and Stories’ section as the curatorial voice of the museum. So, in a way the institution is differentiating the space where people can have a voice from the one reserved for curators, which is part of a more traditional, academic concept of knowledge (Simon, 2008).[21]

Simon

The question is how you translate these community stories into something that can be curated by a formal institution rather than something that’s held within a group of people. There is, for example, a very active group of Windrush Nurses in Leeds who told their story through the Thackray Museum of Medicine.[22] Another example is the AHRC project Digital Tools in the Service of Difficult Heritage: How Recent Research Can Benefit Museums and their Audiences (2014). This is, for me, a really good example of negotiation, of how people work together sensitively to tell particular stories across public and institutional boundaries.[23]

We then moved on to consider what type of space open conversations could take place in and used Wikipedia as an example of a non-institutional platform – accepting that it still relied on traditional knowledge infrastructures, the use of secondary sources, notability and a traditional encyclopaedia concept. This led to consideration of the importance of non-written knowledge, especially in relation to individual stories.

Simon

In a Wikipedia article, where there is this idea of the sole author, there is the sense of academic rigor that’s needed, particularly in historical subjects.[24]

Stuart

This is a structural problem for us. Wikipedia relies on secondary sources. This worked quite well for the past twenty years, but it excludes a lot of knowledge. This originated from the decision of being an encyclopaedia and it falls into that particular structure. You can’t really write anything speculative on it, and even some subjects which are clearly encyclopaedic are sometimes pushed out by people who just don’t know what they are.

Arran

I think there is a really interesting tension there. Although we’ve got this tool that has the potential to democratise access to and contributions of knowledge in how it’s set up, it still relies on secondary sources. So, it still relies on older forms of knowledge generation to be able to share that knowledge in this accessible form (Pfaff and Hasan, 2011).[25]

Stuart

There’s a project called Wikispore which doesn’t require so much sourcing in it and I feel it is going to be more open to all kinds of contributions.[26] There is a huge potential for oral history, for example. There are fantastic audio recordings on the British Library website, like a steelworker in Sheffield talking about their work in the 1950s.[27] That would work so well into so many articles in Wikipedia in terms of illustrating ordinary people’s lives, and audio recordings are really good for this.[28]

Maggie

The Saltaire collection has a newly retired health researcher at the moment who is looking at a particularly large oral history, 200 pages long, that a Saltaire resident wrote himself.[29] It provides a massive insight into life in Saltaire, particularly during the period between the two world wars. There are wonderful elements in this large file, like who was involved in the Home Guard at Salts Mill during the Second World War.

Arran

This is a really interesting point for us. Because the collections are mainly about notable people, but they contain lots of information about non-notable people, who have not ever really considered ‘entities’ worth formally recording (For example, see Popple, 2020). But that’s where all the real links can really happen. Stuart, what makes a person notable enough to go on Wikipedia?

Stuart

Pulling out these individual stories of ordinary people who may have done interesting things is always a bit of a challenge in the context of Wikipedia. The general notability criteria is significant coverage in multiple sources, not connected to the subject, which is an incredibly high bar to pass. That’s not to say it’s not impossible. And there’s also always ways of writing people into the encyclopaedia without necessarily writing whole articles about them.[30]

We then discussed the potential of social media to both produce and disseminate new forms of knowledge. We were particularly interested in the value of sound and creative approaches to bringing working stories and traditions to life. Going beyond traditional knowledge structures and hierarchies led us to think about what are often seen as challenging and disruptive practices, such as remix culture and meme making.

Stefania

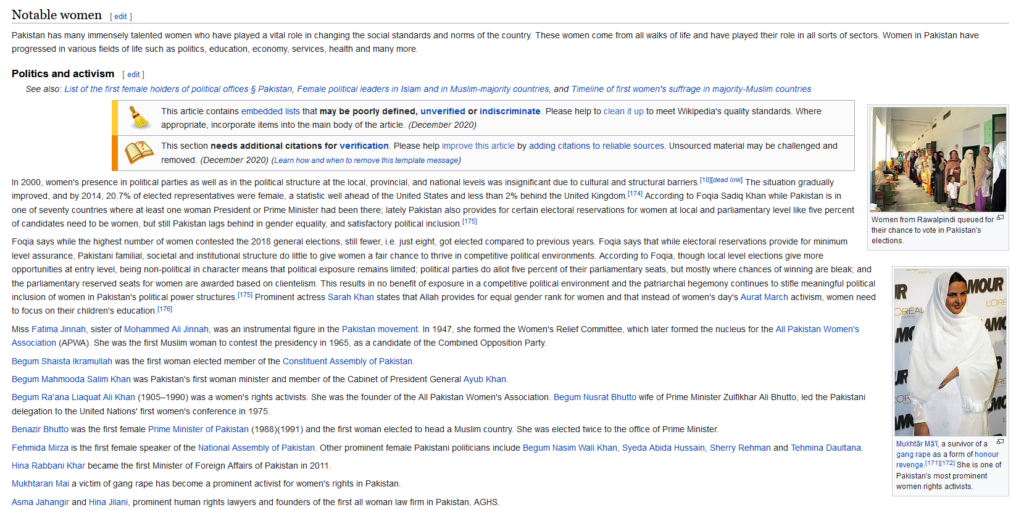

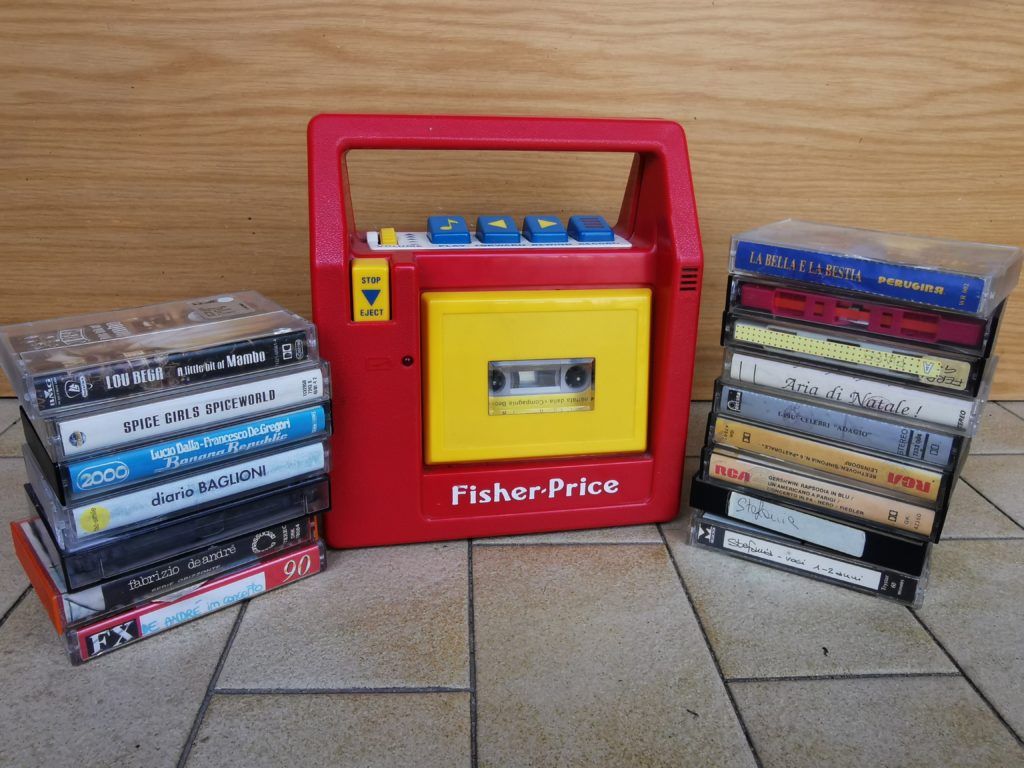

Social media are an incredible source for these kind of individual stories. In the #SonicFriday project, the National Science and Media Museum invited social media users to share their memories around sound technologies, and we ended up collecting 250 digital memories (For more information on this project, see Zardini Lacedelli, Stack and Jamieson, 2021).[31] They were incredibly powerful in expressing the variety of emotional, personal, affective relationships with iconic objects such as cassettes, CDs, synthesizers. These memories were not the type of knowledge museums are used to defining as heritage, they were even different from a more traditional oral history approach, so this project challenged the curators to reflect on their value.[32]

Arran

There are examples of formally collecting this kind of material; the kind that sit outside the more scientific and formal knowledge traditions, and belong to a more folkloric, or social approach.[33] A lot of social history collections were originally called folklore collections. And we can see a lot of what appears on social media as a form of digital folklore (For more information on the development of digital folklore, see Espenschied and Lialina, 2009; de Seta, 2019). People have their own history, and their own ways of communicating in these spaces. And this form of knowledge is a valid thing to be archived and incorporated into our cultural heritage landscape. It’s just a case of reconfiguring the idea of what can be collected.[34]

Stefania

This was exactly the question the curators asked themselves at the end of the #SonicFriday project. Should museums collect people’s digital memories? This can be a disruptive question. And social media can be an exploratory space, for museums, to understand and collect new forms of knowledge (See also Boogh et al, 2020).[35]

Maggie

Talking about new forms of knowledge, the key thing that came out of working together with arts providers in the Bradford City of Culture 2025 bid was that museums and collections are great resources for dramatic and creative representation. For example, an arts organisation and Bradford Museums were able to create a spectacular light show on Listers Mill huge chimney, called ‘The Mills are Alive…’, and projecting a dramatized summary history of that building and the community in Manningham over time.[36] I’m beginning to think that one of the most pleasant ways to share knowledge is through a dramatic or musical work.

Simon

A recent student of mine, Ruxandra Lupu, did a fantastic PhD on connecting heritage organisations, particularly film archives, to local communities and using art practices as a way of engaging with people. She worked in Sicily with regional film archives and people’s home movie collections around notions of belonging and place. She used innovative ways of engaging with people using primary and secondary source materials to create new narratives and new stories around those objects and memories.[37]

Arran

This is part of our contemporary remix culture, isn’t it? (See Lessig, 2008; Manovich, L, 2015)[38] The remixing and reuse of material is a huge part of online digital culture. Participating in the internet or web environment opens yourself up to remixing, whether you want it or not.

Simon

It reminds me of this idea of bricolage, this idea, not even of remixing, but even before of creating something new from other components. In our storytelling platform Yarn, everybody’s stories, everybody’s work stays where it is, but people can quote from it, so they can take pieces away and make another version of that story, but it always links back to the original story (For an account of the project and the resources, see Popple and Mutibwa, 2016).[39] So, you’re always credited. You can’t change the integrity of that, people explicitly know where those ideas have come from.[40]

Here questions of authority and control clash with the concept of personal autonomy, creativity and different traditions of making sense of histories and heritage. The loss of institutional control and creation of potentially disruptive counter narratives becomes an important debate and one which the project will doubtless foster through emergent practices and experiments. The contested nature of history and the surfacing, through storytelling, of hidden and repressed identities and experiences provides us with exciting possibilities for addressing absence and for using the archive as a means of ‘speaking back’.

4. Challenges

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221809/005Our final theme looked to the future and explored a series of practical issues and challenges that can and do act as barriers to the creation of knowledge. These were seen as a mixture of legal frameworks, institutional practices, resources and sustainability, training, and clashes of tradition.

Copyright and licencing, for example, were seen as direct and often intimidating blocks to activity and were often anxiety inducing for all parties. The shifting nature of legislation, further complicated by Brexit, have added to these anxieties that often forestall activities and prevent the use of different types of data and creative outputs. The notion of a ‘creative archive’, for example, is severely limited as are opportunities to combine and remix different data sets and combine intuitional and non-institutional narratives.

Stefania

This idea of change and remix is a huge challenge in terms of authority and authorship, isn’t it? In the Museums of the Dolomites project, the museums shared their images on social media to participate in the #DolomitesMuseum campaign. But when we asked them to publish this material again on a shared digital space provided by the virtual museum of the Dolomites, some of them asked for a protective license of their content.[41]

Arran

This is a really grey area, which I think is interesting. There’s this view that to upload something onto Wikipedia or onto a cultural heritage site might feel like a more formal thing than sharing on social media. And I think that’s why there is still this reticence about the idea of collecting from social media, and perhaps a discomfort from some people that their mindless drivel, posted late night on Twitter, might somehow make it into a museum or archive. Perhaps even invasive, even though users sign exclusive rights to their content away when they agree to the platforms T&Cs.[42]

Maggie

I think one of the reasons people feel perfectly OK about putting something on Facebook or Twitter or Instagram themselves is that they feel in control of it. They don’t think by doing so that the posted material is now ‘out of control’, but the minute you talk about a more stable structure, such as the work you have mentioned Stefania, then they may start to think and also believe that they could be open to criticism from someone who has more knowledge.[43]

Stuart

This is a difficult subject because people want to maintain a bit of control over content they’ve put work into, or put their labour into, and that has to be respected. If you’re dealing with people who have collections and photographs it’s very hard to deal with the intellectual property issues.[44]

Maggie

The volunteers who come here to do this kind of research work have an expectation that their work will be shared. But we have started to realise that we need to protect them a little as well. We have begun to ask ourselves whether we do we need something that prevents misuse of their material; for example, by others radically changing it so that the original meanings are lost or, passing it off as someone else’s work. At our next board meeting (July 2022) we’re actually looking at a Creative Commons license that allows sharing but perhaps doesn’t allow changes without crediting the original source or perhaps helps prevent commercial use.[45]

Stuart

The problem with non-commercial licenses is that legal definitions of commercial use can be incredibly vague and can extend into areas of education or artistic expression and restrict use in the kind of areas you perhaps intended.

Arran

It’s really challenging when you put your content online, you can apply licenses to it and it will stop big commercial usage maybe, but this still won’t stop this kind of amateur reuse and playfulness and taking of material and forming new things. I think this kind of more ground-rooted remix culture won’t be put off by licensing structures.

Stuart

The principle is you have to give up some control. You have to give up certain amounts of ownership and sometimes all ownership in order for your work to reach the world, and whether that’s a price worth paying varies between groups of people. It doesn’t have to be all or nothing, there can be certain elements of things which can be very open to certain elements which are kept closed. This is a constant kind of negotiation with knowledge producers and knowledge holders.

Maggie

Also, because, for continuation of knowledge, you need to be able to change things. Recording history is always difficult, it is subjective to some degree, and you do a piece of work and then later on someone finds previously unknown documents and it actually changes the understanding of the first piece of work.

Stuart

There is the factor of how far you want your work to travel and generally the more open you have it, the further it can travel, and the more people can, as Maggie said, build on it. What you add to Wikimedia projects can be used to build other knowledge, and it can become greater than the sum of its parts. Which I think is the opportunity we look for.

The languages and traditions of different actors were also seen as a barrier to collaborative working and sometimes helped to enforce hierarchies and misunderstanding. Setting the terms of collaborative activities and the nomenclature of research are vital to ensure parity of experience and opportunity and foster mutual understandings. The role of language and the power it often exercises are another ongoing theme we are keen to explore and develop through our own interactions.

Stuart

Another challenge is metadata. Being respectful of people’s nomenclature and language and words being used to describe things, while trying to reconcile that with a more top-down ontology at the same time. Wikidata[46] has a lot of room for people to input things on their own terms. That could literally be like a full language or dialect or just terminology. So those things are quite important to preserve and not necessarily translate into standard English or something like that.[47]

Stefania

Do you have a curatorial role in relation to what people write?

Stuart

It depends on the project; you have to give people guidance on what’s going to stick and what’s not going to stick. Wikipedia is very formal and needs to be done in a certain way, and you have all these boundaries and constraints on what you can contribute. You probably aren’t curating it in as much as you’re saying, “Well, we’re looking for this, this and this.”

Simon

This is the idea that there are specific sets of protocols we give to people when we want to engage with them, and this is a challenge. One of the things that I’ve come across a lot is that people have their own sets of practices within the community or within an organisation or within a small group of people. However they define themselves, they have a language that they use that they mutually understand. They have a set of ways of doing things, they think about ownership in a particular way. For example, in one of the projects I worked on in Scotland we had a lot of resistance to doing things digitally. It was actually a conscious choice to say, actually, we want to work with paper (For a discussion, see Duffy, 2020).

Stuart

This this is a bit of an issue for Wikimedia, ideologically, as a movement, and this is not uniform and things have changed a little bit, we’re a bit like “give us all the information and we can share and everyone shares all the information and that’s great,” but not everyone believes that. And it’s hard to reconcile with certain projects, for example, in indigenous language projects where the history of exploitation, ownership and control are quite important. So, we need to balance this open approach with respect for the ownership of the work.[48]

The question of building sustainable resources and practices is key to the success of our joint enterprise and developing an approach that has sustainability at its core will be one of our biggest challenges. Digital resources in particular are often ephemeral, underfunded and soon become technologically compromised or under-maintained. The internet is littered with thousands of redundant sites representing a large investment of public money and citizen labour. The challenge to avoid future waste, duplication and lost knowledge is uppermost in the aspiration of TaNC and ensuring that collective endeavour remains visible and ongoing is perhaps one of our biggest challenges.

Simon

You can reach a lot of people very quickly using digital platforms, but they are also very ephemeral, and these links that we make between data and between individuals are also ephemeral because people pass away, data disappear or it degrades. So, there’s always this sense of limited sustainability and this idea of running different systems at the same time. I know there have been debates about Wikipedia’s sustainability over the years in financial terms.

Stuart

From a Wikimedia point of view, Wikipedia has shown that it’s pretty sustainable as a project. It is incredibly well funded. But it’s not a big website to support, it’s not a Facebook, it’s not a YouTube, it’s a fraction of the sort of gigabytes of actual data.[49] There is always a risk that community coming along might delete your stuff and that’s why things have to really belong on Wikimedia projects in order to have that longevity. But as a way of creating a kind of backup or having copies around the world, this means there is always going to be a copy of this image somewhere on some server. It’s definitely a sustainable thing, but also there’s a stewardship as well.

Maggie

In terms of sustainability, digital preservation is equally important for our collection as digital sharing. One of the things that we’re very keen to do in Saltaire is to consider whether ‘secondary source materials’ should perhaps be preserved in our internal collection management system. So, in 100 years time perhaps when someone is looking for what was of interest in Saltaire in 2020 there should be some information available that has been digitally preserved.

Stefania

This is one of the key challenges of the contemporary museums. It requires specialised skills, resources, but also a different mindset as to what should be digitally preserved. In the Congruence Engine project, we often reflect on the fact that the museum catalogue rarely captures the curatorial knowledge that is expressed in an exhibition. The archival records are often thin and usually contain the key, biographical information related to the object: place and date of creation; author or inventor; material and dimension; a short description. They don’t usually capture the kind of contextual information that you might find in an exhibition or in a digital narrative, and they don’t usually capture personal responses to the object. In the #SonicFriday project, we started to reflect on how the people’s memories on sound technologies could be linked and embedded in the object record.[50]

Arran

Yes, I totally agree. There are huge questions around digital preservation and cataloguing for museums. The Science Museum Group is one of only a handful of museums in the UK that specifically employ any digital preservation specialists (Tate and Museum of London are others I know of). Then when it comes to cataloguing, despite our sectoral standards being quite explicit that cataloguing is never a finished process and most collections management systems providing space to record new information found during research, engagement projects and exhibitions, there just isn’t a culture of recording that information back in a central catalogue (See also Miles, Cordner and Kavanagh, 2020).[51]

There are also a series of institutional barriers that we are keen to explore in allowing institutions and collections of varying scales to work together across permeable digital membranes. The right to access and engage is unwritten, but the capacity to engage is often wholly contingent on resources and skills base. This is something we see as an ongoing challenge we need to explore across the whole project.

Maggie

The Saltaire Collection will never be in a big building, as a traditional museum that people walk around. Although we will have a little more space in a shared new building from 2024, we will always be a dispersed museum. Digital methods will remain the main way that we can share the knowledge we hold.

Stefania

But also, the Saltaire collection and research community is a really great example on how a museum can involve people and collecting different types of material and build its collections from the bottom up. I think there is an issue here in terms of how we might bring this participatory approach within bigger institutions such as National Museums. In the Museums of the Dolomites project, we noticed that the small community museums were more open to these forms of engagement and knowledge co-creation. The bigger the museums were, the more difficult it was for them to embrace these approaches (See also Zardini Lacedelli et al, forthcoming, 2023).[52]

Maggie

It’s true. We’re using people’s interests and passions and if they get involved because they want to research and write, or to collect an oral history, they can be encouraged to do so. And that is more feasible when a collection is small and does not have lots of formalities. I suspect that there are other small collections around that may have the same advantages.

Simon

Yes, perhaps it is sometimes easier when working at a smaller, more intimate scale. I have worked with several large institutions and there are certainly problems that are baked-in at scale. There are often competing and unrealistic pressures placed on meagre staff resources, internal layers of bureaucracy and fears about ceding institutional authority or perceived threats to institutional reputation that limits the ability to collaborate and make data freely available.

Stefania

The question is what can the national, large museums and institutions learn from the smaller, community museums? The ecomuseum is another great example of a type of museum which has been conceived around community participation and co-curation of heritage (See Rivière, 1980. See also Rivière, 1985).[53] But this museum category has been mostly applied to the protection and development of natural resources and local heritage and has not been extended to other kinds of institutions. This is not just a way of thinking about different types of museums and collections; it is a way to understand new forms of heritage and conceiving museums as institution (See Zardini Lacedelli, 2018).[54]

Maggie

Can partnerships be brokered between large museums and small localised collections, where the larger partner offers interesting lines of enquiry and some resources that enable the smaller partner to work to gather the ‘story’ that could be told in more detail? This would mean giving up some of the formalities of ‘ownership’ of objects for the larger partner and some changes in curatorial practices.

Conclusions and future steps

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221809/016Working on this piece made us reflect on the opportunities of conversational and dialogic writing in research (See Brownlee-Chapman et al, 2018),[55] and how this form reflects the very nature of the Congruence Engine project. The article originates from two online conversations which have been, for us, a space where we could pause and listen, share our previous experiences, draw in our different knowledges and perspectives, and respond to each other. The ways in which the different ideas and examples sparked and catalysed reflect the live exchanges that are at the very core of Congruence Engine. Inspired by the Systemic Action Research methodology (Burns, 2007), the project involves participants from different backgrounds – curators, historians, digital humanities scholars, data scientists – in a series of collaborative explorations around the potential of connecting collections. The project advances through forms of exchange which allow us to embrace multiple perspectives, approaches and ways of knowing.

We believe collaborative and dialogic writing can be a useful means of developing and reflecting future conversations across the Congruence Engine project and can play a key role in enabling participatory approaches in the creation of a National Collection. We would be extremely interested in hearing other ideas and opinions about developing collaborative writing and how we might use this form to create a common ground across the different registers, languages and knowledges of the project participants.

As for the themes that have emerged from this initial series of conversations, the challenges of community building, the nature of different kinds of knowledge, digital preservation, as well as the issues of power, remixing, ownership and control, are all extremely relevant not only for our project, but for the future of heritage institutions.

It is important to say that this is a starting point for much longer and more open discussions as the project evolves and more people come on board. Conversations are never definitive or neatly concluded and we feel it is important to register this in the extracts we have used to give a flavour of the themes and approaches which mark this project out as such a unique and collaborative venture. We hope that others will pick up where we left off.

Tags

Footnotes

Back to text