Medieval Women: Voices and Visions, British Library exhibition review

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/252308

Abstract

Dr Kierri Price reviews the Medieval Women: In Their Own Words exhibition at the British Library, with interjections from four fellow medievalists to reflect the excitement of the exhibition. Dr Price’s interlocutors include Dr Diane Heath (medievalist and a guest editor of this issue of the journal), Professor Louise Wilkinson from the University of Lincoln (who was on the advisory panel for the exhibition), Dr Harriet Kersey (expert in noblewomen of the thirteenth century), and Dr Sheila Sweetinburgh (Principal Research Fellow and Co-Director of the Centre for Kent History and Heritage at Canterbury Christ Church University).

Keywords

British Library, Exhibition review, medieval women, medievalism

Review

This review of the British Library Medieval Women exhibition takes a slightly unusual format. The main text is by Dr Kierri Price, post-doctoral scholar in medieval history, who also contributed discussion of the medieval birth girdle in the exhibition catalogue. There are also additional contributors. Four medievalists – Dr Diane Heath (medievalist and a guest editor of this journal issue), Professor Louise Wilkinson from the University of Lincoln (who was on the advisory panel for the exhibition), Dr Harriet Kersey (expert in noblewomen of the thirteenth century), and Dr Sheila Sweetinburgh (Principal Research Fellow and Co-Director of the Centre for Kent History and Heritage at Canterbury Christ Church University) – visited the exhibition together and had several discussions on their thoughts and reactions afterwards. These voices, along with those of other experts and commentators, are added here as interjections, exclamations, expertise and shared conversation, giving readers a sense of the excitement generated by the wealth of texts and objects in this recent exhibition. This approach mirrors the aim of the British Library curatorial team “to put women’s own words in the spotlight.”[1]

A group of us met Professor Louise Wilkinson at the British Library in London to visit the new Medieval Women exhibition there. Louise had been involved in creating the exhibition as a member of the advisory group, and they have done an excellent job. Interestingly, many of the manuscripts and documents on display have come from the British Library and The National Archives, with some from the Wellcome Collection and the V&A, as well as Oxford and Cambridge, and the Louvre in Paris, which is perhaps not surprising, but from a Kent perspective there was one very interesting panel showing the saints associated with Dartford Priory that came from Leeds Castle and is dated to the years before the dissolution of the Dominican nunnery. The exhibition is arranged thematically, such as topics relating to the body through medicine, anatomy and childbirth, and one of the exhibits is a birthing girdle. As you might expect, the majority of artefacts relate to the medieval Christian West, but there were some from much further afield, including gold coins from the first female Egyptian sultan from the mid-thirteenth century.

– Dr Sheila Sweetinburgh, blog post, 27 November 2024

What is there to know about women in the medieval period?

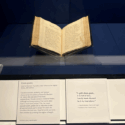

If you think there is no surviving evidence or believe that there are few (if any) interesting stories to tell about women in medieval times, the British Library’s exhibition Medieval Women: In Their Own Words (25 October 2024–2 March 2025) offers a striking challenge to that viewpoint. With an impressive collection of manuscripts, textiles, sculptures, coins, marriage chests, pilgrims’ badges and even a lion’s skull, this exhibition provides a counternarrative to a persistent cultural stereotype – that medieval women did nothing important and said nothing important. Instead, Medieval Women reveals that women’s voices and lives were often rich and varied, and although their experiences may have been sidelined in the historical record, they have not been silenced.[2]

The Medieval Women exhibition, like the accompanying hardback, is divided into four sections: Private Lives, Public Lives, Working Lives, and Spiritual Lives. There is a sense of drama and spectacle upon entering the exhibition space. From the main entrance of the British Library, the visitor walks past the tantalising offerings of the shop (embroidery and calligraphy kits, jewellery and clothing, and a tempting selection of books) into a dimly lit foyer.

The room opens out suddenly, offering the first view of the exhibition. It is airy and spacious, almost as if entering a cathedral; standing at the top of a flight of stairs, visitors overlook a space demarcated by architecturally styled fabric divisions indicating house, castle and church, and wide lengths of cloth hanging from the ceiling. The soft, warm lighting and calm, blue tones of the fabric are inviting, encouraging visitors to descend the staircase, where they are met by a life-sized replica statue of Queen Eleanor of Castile (1241–1290). Eleanor was the beloved consort of King Edward I, whom she had married when aged 13. After she had died aged 49 on 28 November 1290, Edward set up impressive stone crosses decorated with heraldic shields and statues to mark the route of her cortege from her place of death in Harby (Northamptonshire) to where her body was interred at Westminster Abbey. Her entrails were entombed in Lincoln Cathedral.

A queen of ‘contradictions’, Eleanor of Castile was pious, beloved by her husband the king but not, it seems, popular, partly thanks to her avaricious land-grabbing tendencies.

– Diane Heath

Three manuscripts accompany Queen Eleanor: Hildegard of Bingen’s Liber divinorum operum (Book of Divine Works, which the Abbess wrote between 1163 and 1173); Christine de Pizan’s Book of the City of Ladies (1405), and a letter from Alice Crane to Margaret Paston, which includes the following sentence:

Thanking you of the great cheer that I had of you when I was with you last with all my heart.

– Alice Crane, Letter to Margaret Paston, c. 1455 (BL Add. MS 34888, f. 118)

This cluster of four objects offers a microcosmic model for the rest of the exhibition, succinctly introducing themes of politics, spirituality, culture and domesticity, and showcasing the wide range of material from the performatively public to the intimately private.

Private Lives – Body and Health

The first section of the exhibition, ‘Private Lives’, begins with an exploration of ‘Body and Health’. To begin on a lighter note, there are beauty products and recipes, and an ivory hair comb.

I loved the cosmetic preparations that you could smell in this section. All the interactive exhibits – and especially the recorded sound ones – were great.

–

Harriet Kersey

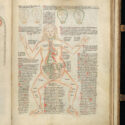

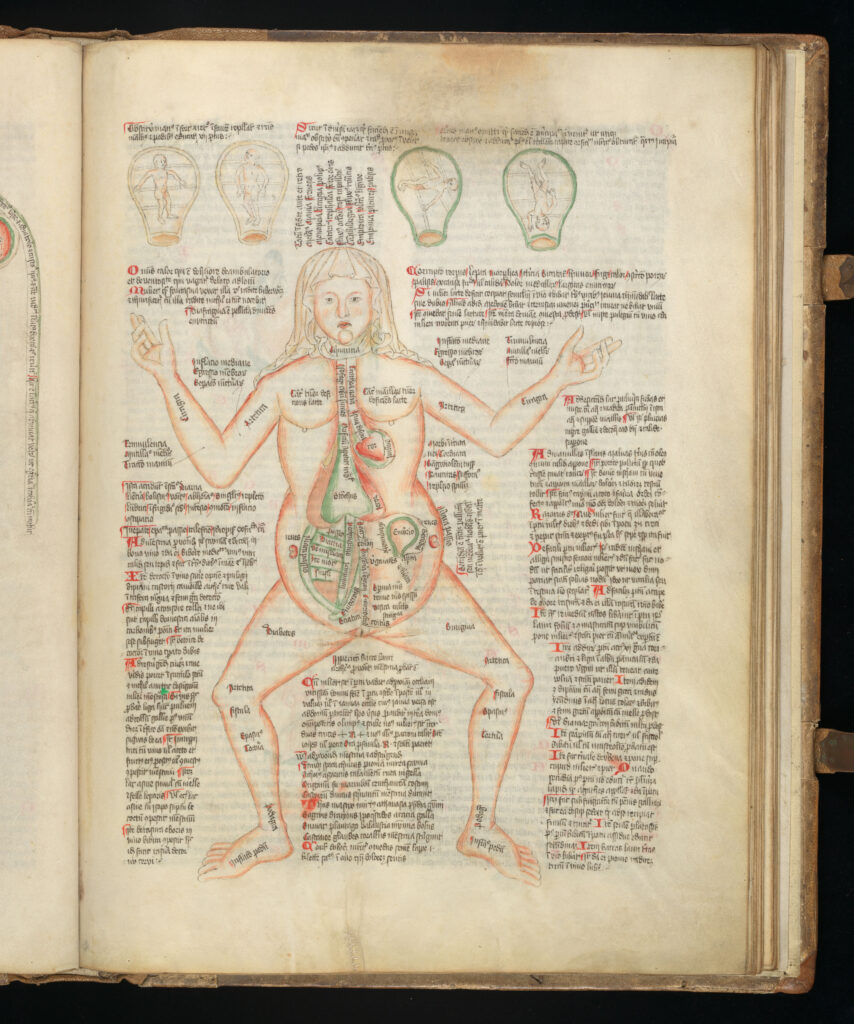

On loan from Wellcome Collection, the Wellcome Apocalypse is opened to reveal the ‘Disease Woman’, an anatomical diagram of a woman labelled with names of various body parts and their associated diseases.

She faces the viewer directly, her modestly wimpled head in stark contrast to her exposed, naked body. In a culture that depicted (typically white, able-bodied) male figures as universally representational for medical diagrams, the ‘Disease Woman’ provides an alternative perspective, illustrating information specific to women’s bodies. Notable among her illustrated internal organs is a uterus, labelled ‘Embrio’ – she is pregnant.[3]

Wimpled but akimbo is certainly a jarring image, Diane. As she is pregnant, perhaps the wimple indicates her married status?

– Harriet Kersey

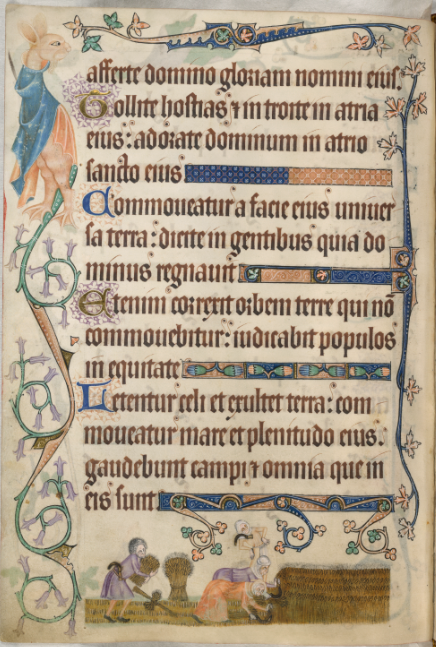

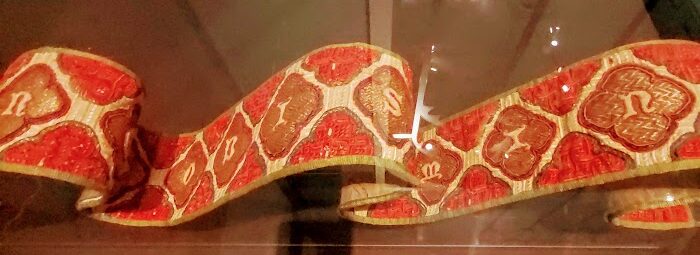

British Library manuscript Harley Roll T11 offers a more intimate, personal account of pregnancy. This long, thin parchment roll, now known as a ‘birthing girdle’, offered protective assistance against many potential hazards, including battle, sudden death, pestilence and childbirth. Among its devotional texts and images is an illustration of Christ’s Side Wound, which has been touched or kissed devoutly to such an extent that the pigment has worn away completely in the centre. As the name ‘birthing girdle’ suggests, this manuscript could also have been worn as a girdle or belt, wrapped around the body in a pregnancy or labour context. Rolls and scrolls often end up flattened when on display, but this birth girdle is displayed in a curved setting, highlighting the dynamism and materiality of the object.

A comfort belt of charms, prayers and amulets at a most dangerous time in a woman’s life.

– Diane Heath

This section of the exhibition also reveals poignant examples of physical and mental ill-health and disability. A prayer book of Queen Joanna I of Castile, known traditionally as Joanna ‘the Mad’, attests to her religious devotion in the face of tragic circumstances; her family accused her of being unfit to rule, and she spent most of her adult life in confinement, mistreatment that likely worsened any mental health conditions.

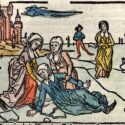

A late fifteenth-century book with woodcuts celebrates the life of the patron saint of ice-skaters, St Lidwina, who was badly injured in a skating accident and then devoted herself to prayer and charity alongside periods of illness and terrible pain.

The exhibit captions are diplomatically neutral, disguising the often-voyeuristic characterisations of Johannes Brugman’s Vita Lidwinae. He exposes Lidwina’s disabled body as a grotesque spectacle, and the exhibition visitor is subtly implicated in their own responses to Lidwina’s story.

Private Lives – Family and Household

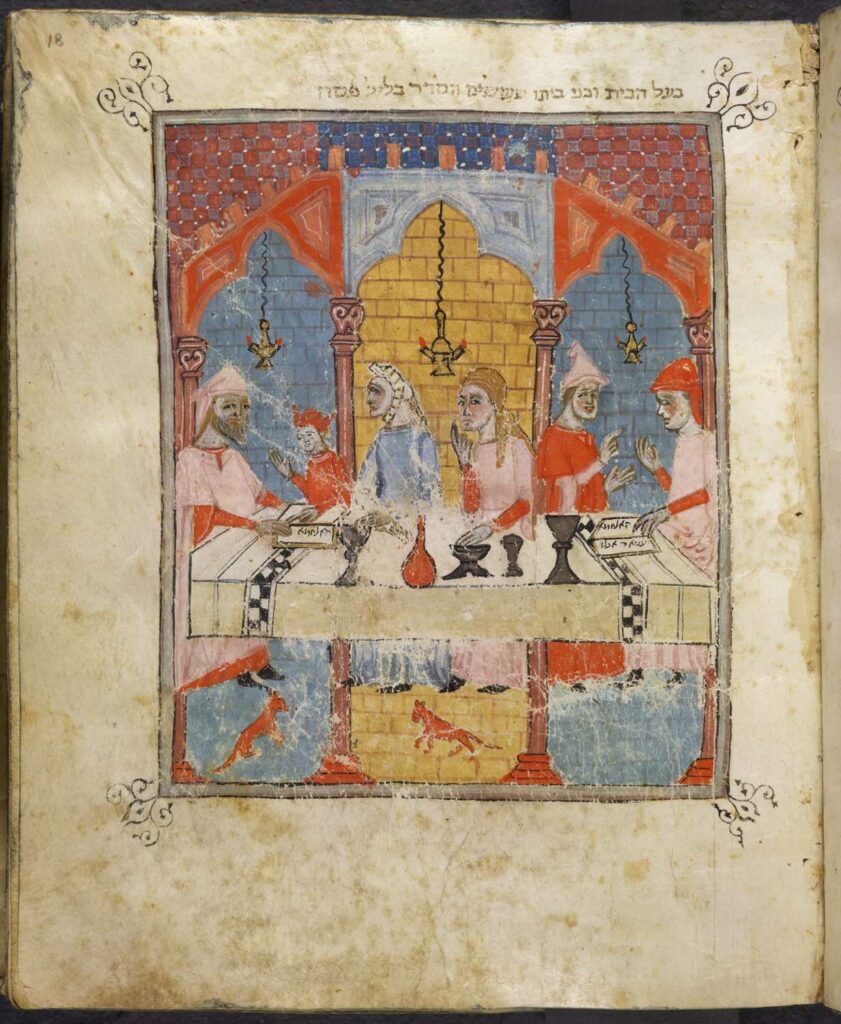

The next section, ‘Family and Household’, demonstrates the diversity of domestic life for medieval women. Despite the inequality of education and legal rights, women’s testimonies show that their roles were often active and vibrant. A primer from c. 1445 illustrates a classroom scene with four young girls, and two alphabets on the facing page; a Hebrew prayer book from 1469 contains various illustrations of a young woman performing Jewish rituals (the Sister Haggadah from Eastern Spain). Both manuscripts make it clear that some women could be highly educated and actively involved in religious ceremonies – even when those roles were usually assigned only to men.

However, not every exhibit paints such an encouraging picture. Opportunities could be highly variable depending on wealth and social status. For example, in marriage women lower down the social scale might marry later in life, and have a choice over their husband, whereas wealthy families arranged marriages for political and financial gain, with girls often betrothed as children. Next to the sumptuous marriage chest of Elizabetta Gonzaga is the sobering statistic that the average age of medieval English royal women at marriage was sixteen.

King John married Isabella of Angouleme in 1200 when she was about 12. Isabella outlived him and then married her first betrothed, Hugh of Lusignan. They had nine children. Isabella gazumped her daughter to get him!

– Harriet Kersey

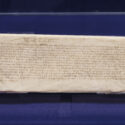

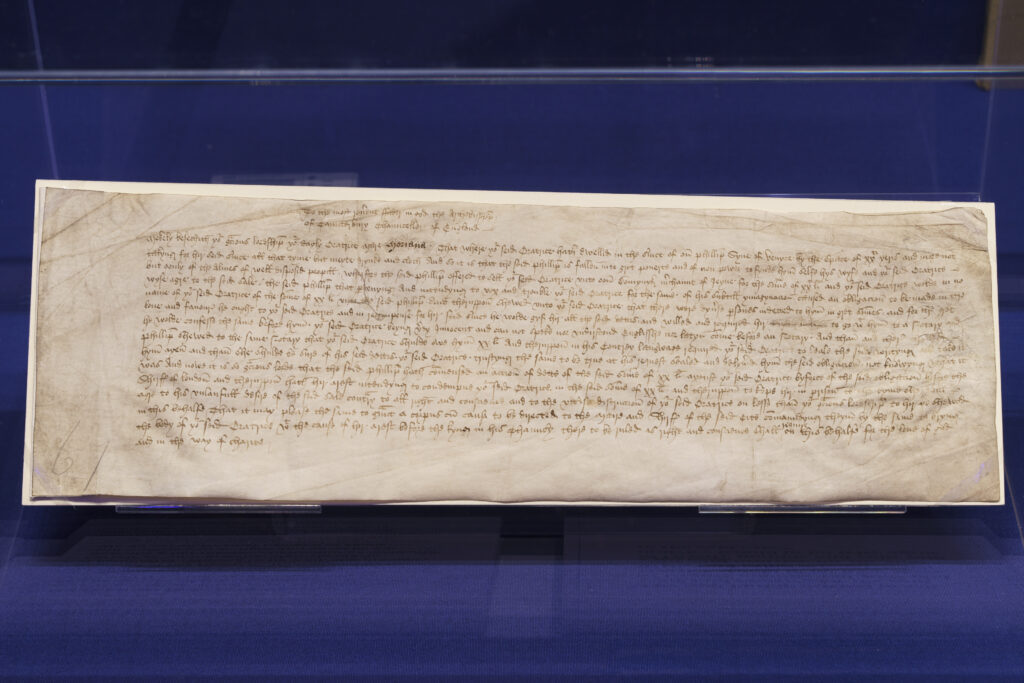

Public Lives

It is in the next section, ‘Public Lives’, that the exhibition explores more fully the themes of power, inequality and exploitation. Women sought power and influence in numerous ways, from across the whole social spectrum. An account of the Peasant’s Revolt in Cambridge records the protesting voice of Margaret Starre, an old woman whose livelihood was threatened by the privileges of the University. She holds equal space next to Empress Matilda, who nearly became the first ruling queen of England – the foundation charter of Bordesley Abbey styles Matilda as ‘empress’ and ‘lady of the English’, and her unusual round seal[4] depicts her with both crown and sceptre (Foundation Charter, Bordesley Abbey). Dated to 1141–1142, the charter was issued by Matilda during a bloody civil war, when nobles led by Stephen of Blois refused to accept Henry I’s daughter as their ruler.

Chroniclers criticised Matilda for being harsh and unwomanly.

– Louise Wilkinson

‘Public Lives’ also includes a particularly striking artefact: a Barbary lion skull loaned from the Natural History Museum, London. An account book details expenses incurred during Margaret of Anjou’s luxurious journey to England to marry Henry VI in 1444, including the upkeep of a lion (which would have travelled with Margaret and been kept in the Tower of London menagerie). This skull, found in the moat of the Tower in the 1930s, has been carbon-dated to between 1420 and 1480.

Scholars believe that this skull may have been from the actual Lion given to Margaret of Anjou as a wedding gift in 1445! I love Katie Wignall’s Look Up London blog about London connections of some of the Medieval Women exhibits, including Margaret of Anjou A Glimpse Into the Lives of Medieval London Women.

– Diane Heath

A hoard of gold coins, a fifteenth-century silver-gilt cup, a walrus ivory carved cross, and a satirical phallic badge are interspersed amongst manuscript charters, chronicles, psalters, horoscopes and letters in the remainder of this section, offering a compelling fusion of the textual and the material.

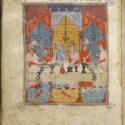

Working Lives

‘Working Lives’ displays a wide variety of women’s experiences and employments way beyond those of queens and noblewomen: women recorded here were silk workers, scribes, notaries, illuminators, booksellers, printers, and writers. For example, in the mid-fourteenth century Jeanne de Montbaston (c.1325–c.1353) had worked with her husband in a Paris manuscript workshop where, amongst other books, they produced copies of the runaway bestselling (if hugely misogynistic) poem Roman de la Rose by Jean de Meaune. Jeanne portrayed her husband as the scribe and she as the official illuminator, working in their studio (Paris, BnF ms. fr. 25526, fol. 77v), and she later ran the workshop after her husband’s death. Her lively marginalia in the same volume includes a nun picking penises from a tree (fol. 106v), a well-known image, but the work shown in the exhibition is Marco Polo, Le devisement du monde (The Description of the World), in London, British Library, Royal MS 19 D I. Works by Christine de Pizan (1364–c.1430) are also on display: and a copy of her collected works, the ‘Book of the Queen’, which Christine presented to Queen Isabeau of France in c. 1430, is one of the British Library’s most treasured manuscripts. Christine was a prolific author, poet and court writer, and she was also a scribe, illuminator and workshop owner (a rara avis in the Middle Ages). Her books include The City of Ladies and The Treasure of the City of Ladies, which have been described as early feminist writings because she took issue with Jean de Meaune’s viewpoint in Roman de la Rose that women seduced men.[5]

Particularly effective in this section was a nineteenth-century copy of the poetry of Hafsa bint al-Hajj al-Rukuniyya accompanied by an audio recording. A twelfth-century poet from Granada, Hafsa was a privileged woman from al-Andalus (Islamic Iberia) who engaged in a poetic exchange with her lover Abu Ja’far, and the inclusion of this later copy of her work in Medieval Women reveals the enduring interest in medieval women’s writing.

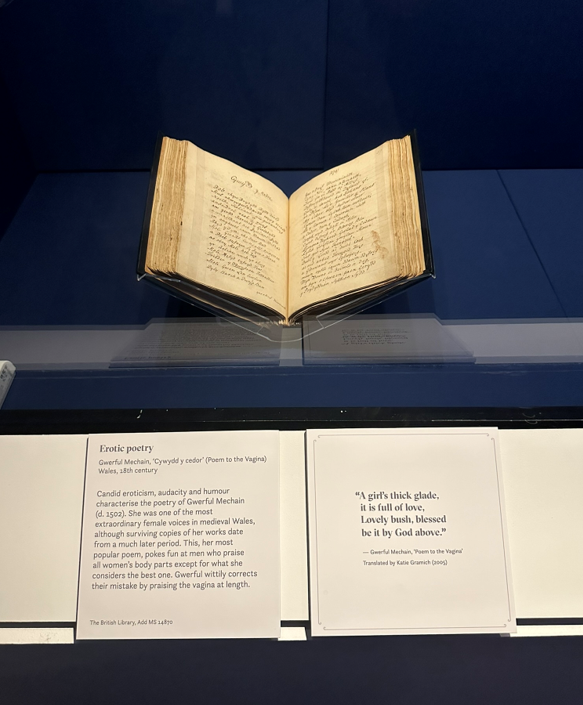

Hafsa’s love poetry reminded me of Margery Brews’ Valentine message to John Paston. The Welsh poetess Gwerful Mechain had rather a different and much more direct take on love and sex. These texts are medieval women’s unfiltered responses to love – rare, real, raw – and powerful.

– Diane Heath

Ordinary women’s working lives were highlighted in another British Library treasure, the Luttrell Psalter, in a scene showing women gathering in the harvest with sickles – backbreaking work.

Besides this harvest scene, there are other telling images in this Psalter depicting women at everyday work. For example, milking sheep, feeding poultry, tending the fields, spinning, taking grain to the mill, and carrying heavy loads.

– Sheila Sweetinburgh

The enslaved girl Marta’s bill of sale was a signal reflection that modern day sex trafficking has old roots. Yet there were more positive instances of women’s work. For example, the small scrap of parchment that reveals Joan du Lee petitioned Henry IV to allow her to travel throughout the kingdom to practice her ‘fisik’ (medicine) (TNA SC 8/231/11510).

Spiritual Lives

The final section of the exhibition, ‘Spiritual Lives’, was marked by an empty space bracketed by floor-to-ceiling cloth hangings. A stained-glass window is projected onto the fabric, shifting subtly between images and refracting golden light onto the floor. In comparison to the densely clustered glittering treasures of the previous ‘Public Lives’ section, this open area offers room for contemplation and introspection and the nearby manuscripts and printed texts echo this shift in tone. Anthony Bale, contributor to the accompanying exhibition publication (2024, p 188), sums up this section as being about ‘mystics, visionaries and heretics’ and their revelatory religious writings and visions as ‘direct experience of, and communication with, the supernatural’. There are works by anonymous writers, and named ones, such as the anchoress Julian of Norwich (d. c. 1416) who experienced sixteen visions after becoming dangerously ill and, upon her recovery, wrote two treatises about these ‘shewings’, full of warmth, compassion and yearning for God’s love. These are the earliest surviving English-language works attributed to a woman. The only surviving copy of the first version of her Revelations of Divine Love, is shown with a seventeenth-century copy of the revised ‘Long Text’ of her Revelations. Here too is a medieval English translation of the saint and mystic Catherine of Siena’s treatise Il dialogo della divina provvidenza (The Dialogue of Divine Providence, written c. 1377–1378) called The Orcharde of Syon, a dialogue between a soul and God, in which she envisioned Christ as a bridge between the world (and all its troubles) and Heaven. Perhaps even more well known is the sole manuscript copy of Margery Kempe’s Book. Margery was a well-to-do merchant’s wife from Norfolk who had fourteen children. She is often viewed as setting out a very public, individual and outspoken journey to spiritual understanding, one that involved penitential pilgrimages to Gdansk, Rome and the Holy Land, wearing white clothes – usually associated with virginity – experiencing many visions of Christ, and given to very public bouts of loud wailing, which we know about through her autobiographical Book that she dictated to male scribes. The sensory aspects of these mystical visions of both Heaven and Hell are showcased in an interactive olfactory exhibit; two small doors can be opened, immersing the visitor in scents of smoke and sulphur, or aromas of caramel and honey.

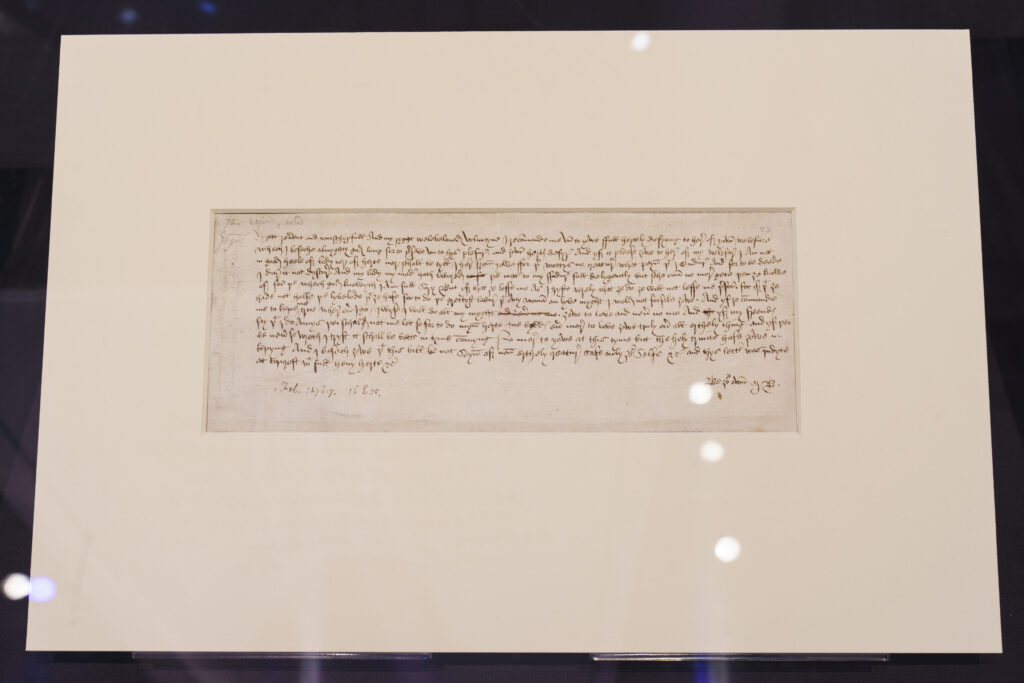

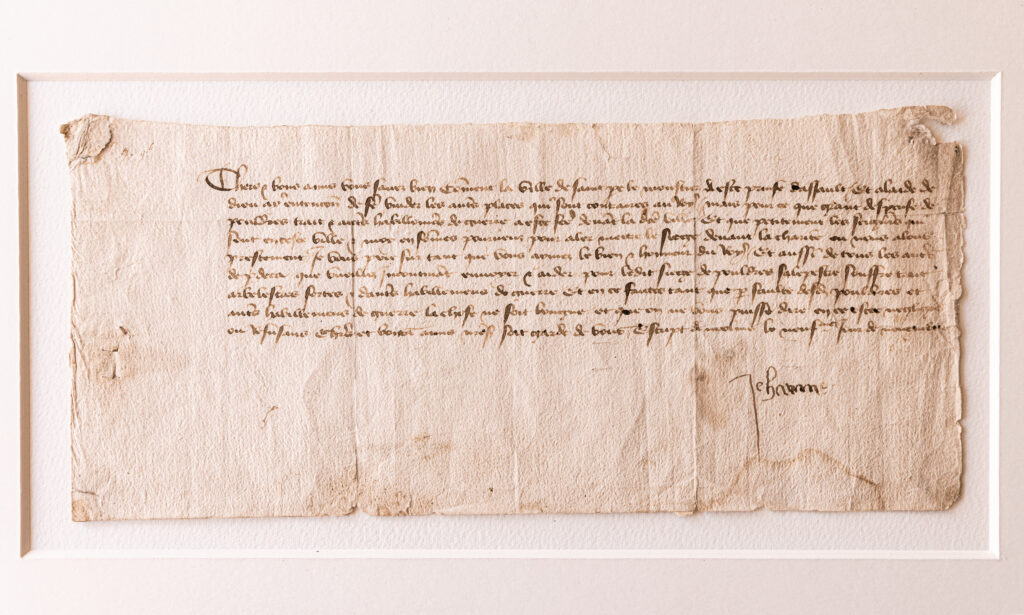

Joan of Arc

Opposite this sensory wall is perhaps one of the most significant artefacts in the exhibition: the earliest autograph signature of Joan of Arc, on loan from Ville de Riom, Archives Municipales. Joan dictated this letter (asking the citizens of Riom to provide gunpowder and military equipment) to a scribe, since she was illiterate, but the shaky signature ‘Jehanne’ is in her own hand. This poignant record of a woman aged only nineteen at her death carries in its uncertain letterforms an emotive mixture of both courage and innocence.

This letter is, unfortunately, in a somewhat inaccessible location: suspended on a wall behind a display case, it is impossible to view at close quarters, especially for visitors in wheelchairs or those unable to lean over the display cabinet. This important artefact also deserves more space and fanfare than it receives in the exhibition. The autographed letter, three manuscripts in a display case, and a subtitled video clip of the 2018 production of Bernard Shaw’s Saint Joan (played by Condola Rashad) are all closely packed against one wall; the film would benefit from a larger screen, dedicated viewing space, and seating, which would also highlight the significance of the material more emphatically.

Cloistered Lives

The last section of the exhibition is dedicated to the lives of nuns: their communities, devotional practice, their literary compositions, their music, their rules and regulations, and their artwork. A Middle Dutch prayer book, c. 1517–23, was made for a woman in the Third Order of St Francis and contains several woodcuts.

Many of these religious prints were hand-coloured and some were decoratively sewn in with brightly coloured silk threads, a meditative creative process that highlights the centrality of textile practice in medieval religious culture. A fourteenth-century embroidered altar band made as an act of devotion is even signed by its maker: ‘Lady Joan of Beverly, a nun, made me.’ This extraordinary textile work of exceptionally high quality, on loan from the Victoria & Albert Museum, is the only surviving piece of medieval English embroidery to record its maker’s name.

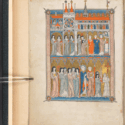

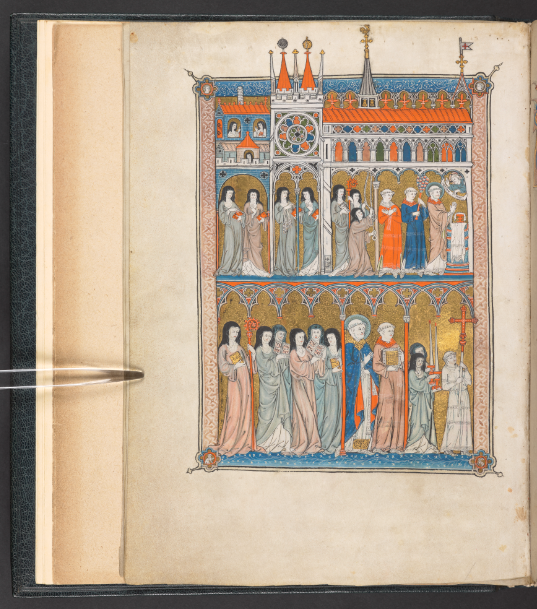

The large introductory image for the entire exhibition comes from La sainte abbaye (France, c. 1290–1300), a treatise on the ideal abbey, showing a detail from a full-page miniature depicting the Abbey and its Cistercian nuns going in procession to mass clutching their choir books, led by their abbess with her crozier. These are personifications of a nun’s virtues, rather than real medieval women.

Helpful captions explain what the object is and why it is significant – there’s a large print guide – while the exhibition handbook adds key essays, and a reading list.

– Louise Wilkinson

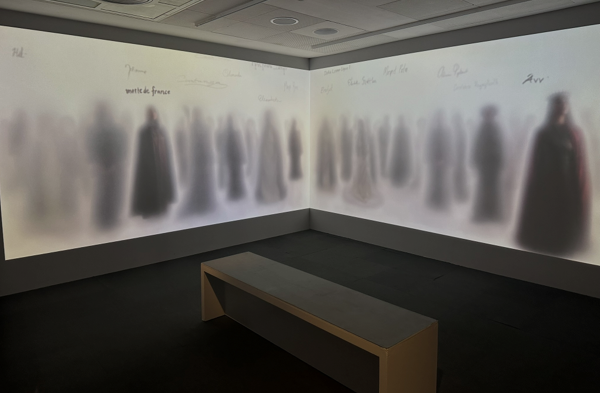

Silhouette Space

The exhibition concludes with a film spread across a two-wall screen of silhouetted female figures. These figures slowly emerge from and disappear into a monochrome mist, accompanied by recorded voices and textual inscriptions recording the names of medieval women from the exhibition while simultaneously leaving space for those anonymous women whose legacies and experiences are as valuable as their named counterparts. The single bench in front of these screens offers a place for contemplation, as well as a welcome chance to sit. Overall, the exhibition would benefit from more seating for a more accessible experience. It is accessible by lift, although this wheelchair-accessible route loses some of the impact of the first view, as the visitor arrives downstairs in a tucked-away corridor. However, accessibility and interactivity have clearly been prioritised in this exhibition: tactile and olfactory exhibits encourage sensory immersion; digital displays allow visitors to test their knowledge of divorce, witchcraft, and medical remedies; and video clips come with both audio and subtitles. There is also recognition of the difficult themes raised by the exhibition (including slavery, racism, misogyny, persecution and murder – all of which were visible elements of a highly unequal medieval society). A comprehensive content warning is provided on a small plaque before entering the exhibition – although this could have been made more visible – and support resources are indicated on the final boards of the exhibition.

Medieval Women covers a vast chronological and geographical expanse and engages meaningfully with a wide variety of topics both playful and serious. Literature is in English, Welsh, Anglo-Norman, French, German, Arabic, Hebrew, Latin, Greek and more. Manuscripts and printed material sit in conversation with a diverse collection of objects. Christianity, Judaism and Islam are all represented. Women are evidently not just cis, white, able-bodied, upper-middle class. Their lives included domestic pursuits, familial love, romantic entanglements, devotional practice, divine inspiration, literary authorship, education, artistic creation, medical practice, agricultural and mercantile labour, slavery, sexual exploitation, royal responsibilities, political revolution, military action and more. While necessarily displaying only a fraction of their numerous stories, Medieval Women offers a valuable insight into the complex and multifaceted lives of medieval women, amplifying their voices and cementing their enduring importance.

A conversation among medievalist reviewers

After our visit the four contributing medieval scholars (Professor Louise Wilkinson and Doctors Sheila Sweetinburgh, Harriet Kersey and Diane Heath) gathered for a discussion, to ponder what we had seen. We all enjoyed and appreciated the sheer amount of objects and texts on display. But what were our favourites? Louise Wilkinson and Harriet Kersey both chose the Bordesley Foundation Charter of Empress Matilda from 1141–2.

This charter is a key document from the Anarchy, the English civil war fought between Empress Matilda (daughter of Henry I) and Stephen of Blois (Henry I’s nephew) and Stephen’s wife (also called Matilda). Louise mentioned that the charter calls Empress Matilda anglorum domina, which has usually been translated as ‘lady of the English’. Yet the masculine form dominus means ‘lord’ – Matilda was a leader, an empress through her marriage to the Holy Roman Emperor and Henry I’s only legitimate living issue. Diane liked Jitske Jasperse’s translation as ‘female lord of the English’, but agreed it is a little clunky.

Nevertheless, the charter emphasises Matilda’s authority. As Harriet pointed out, “And then there’s the seal…” By using the traditionally round format for men it sends another message about Matilda’s adoption of traditionally more masculine forms of authority, because as we all agreed, “Women’s seals were usually pointed ellipses.” The detailing on the seal is really clear, too. It shows Matilda enthroned, with a sceptre and a three-pointed crown and the legend around the edge refers to her as Queen of the Romans ( + MATHILDIS DEI GRATIA ROMANORUM REGINA). However, the seal is not shown in the exhibition as a silk seal bag covers it. This seal bag of blue with woven yellow crosses may have been made from one of Matilda’s own robes, and it is a very rare survival.

What makes the charter so significant?

Well, as Louise said, “This is as close as England gets to a sovereign queen in the Middle Ages. Her father had made his nobles swear allegiance to Matilda; she should have been crowned queen. The lords could not accept a woman’s rule but they also said she was too masculine.”

Behind the issue of the charter there’s also another story. Besides nearly becoming a ruler in her own right, Matilda took the Abbey from the original founder, Count Waleran, who had been given these royal lands for the Abbey by Stephen. She re-absorbed the Abbey lands back into royal landholdings simply by making it a royal abbey and made Waleran witness her charter too. There is a seventeenth-century record of another seal of Empress Matilda dated 1141 (the original was burnt in the Cotton House fire of 1731), which apparently bore the legend ‘MATHILDIS IMPERATRIX ROMANORUM ET REGINA ANGLIE’ (Matilda, Empress of the Romans and Queen of England), but of course those were the expectations before the civil war. Although never sovereign queen herself, as Louise pointed out: “In the end, it was Matilda’s son who succeeded to the English throne as Henry II.”[6]

Dr Sweetinburgh chose the Luttrell Psalter – always a star manuscript because of the quality of its illuminations and amazing marginalia that include rural scenes. It was called ‘a mirror in parchment’ by Michael Camille (1998), not just because of its outstanding illuminations that often depict life in fourteenth-century rural Lincolnshire but also because the many images, including hybrids, monsters and punning allusions to the Latin text speak to the complex social and cultural understandings and challenges faced by this agrarian society, and in particular the problems besetting the patron, Sir Geoffrey Luttrell and his nouveau-riche family.

We all knew that Kierri, who was at work when we visited, would have chosen the birthing girdle as their favourite, as they studied these medieval girdles for their recent excellent PhD.[7] Girdles aided not only individual medieval women but brought women in the community together to aid each other in time of need, a caring hug wrapped around a body often in pain (and before anaesthetics), its inscribed skin of charms and prayers provided (like St Catherine of Siena’s vision) a supernatural bridge between earthly pains and a caring Christ.

Diane Heath appreciated the evidence of marginal voices the exhibition presented, and pulled out three examples: Eleanor, Margaret and Maria. The London part-time barmaid, embroiderer and transgender sex worker Eleanor Rykener was caught in an alley off Cheapside having sex with John Bratby and, when arrested and searched, was revealed to be male. Eleanor refused to change her dress for men’s clothes during her trial.[8] The aged rebel Margaret Starre was arrested after she burnt documents belonging to Cambridge University during the English Uprising (often known as the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381), scattering the ashes and shouting “Away with the learnings of clerks, away with it!” And, as a final example, the black servant girl Maria Moriana, who took her master to court when he tried to sell her as a slave. These strong and powerful stories of very different impoverished women were rarely recorded yet they are vitally important for understanding female non-normative beliefs, actions and emotions.

What would we change?

Here, we were ready to add our own voices and visions (Louise, part of the organising committee, gracefully stepped away from the discussion here). Much more on ordinary women’s lives was something that Sheila had wanted to see.[9] Sheila noted The Smithfield Decretals was not on display (and it is a British Library manuscript, Royal MS 10 E. iv, a set of law codes from France that later underwent a splendid series of illuminations in England). This was a pity as it has a depiction of an alewife, another common occupation. More information and primary sources about the lives of ordinary countrywomen and townswomen would have been welcome. For example, there are a series of rare married women’s wills from Canterbury (rare because most married women’s property went straight to their spouse), but these reveal some women did own property and could dispose of it as they wished, an important corrective to standard views on medieval women’s ownership of property.

Harriet, especially interested in noblewomen’s’ lives, would have liked more jewellery and rich artefacts, although the beautiful crown of Anne of Bohemia (first wife of Richard II), was apparently too fragile to travel from the Bavarian State Museum. The crown is a delicate filigree of golden spires decorated with pink and pale blue gemstones and pearls that look like spring flowers and, more to the point, it is a unique survival and far too valuable to loan, although there is a photograph of it in the handbook. Harriet and Diane both love that it was made in segments so it could be flat-packed when travelling. Harriet also would have liked more scenes of medieval women’s hunting and falconry. There was the early printed Boke of St Albans on hunting on display, probably written by Dame Julyans Bernes (British Library, C.11.b.5), but no images of hawking, for example, such as the many in the delightful Taymouth Hours (see Figure 19).

Diane would have loved a bright and colourful garden path with some seating (there was very little in the exhibition) leading out of the exhibition and set-dressed to represent a medieval garden – perhaps lit by daylight bulbs, filled with insect buzzing, birdsong, herb and rose fragrances. It could be decorated with medieval illuminations of gardens, for example from Le Roman de la Rose and with the audio of voices giving medieval readings. This would have brought together the nuns’ spiritual gardens, as well as the gardens in medieval romances and potager gardens for culinary and medicinal purposes.

A final question: what worked and what did not?

The sheer amount of objects and the many books was a supreme delight. The wonder of seeing unique items – Margery Kempe’s Book, Joan of Arc’s signature, the sultana of Egypt’s gold coins, the Paston letters and Pizan’s Book of the Queen, plus the charters, licenses and records of Medieval European and Mediterranean culture was exciting, impressive and inspiring. The signage was clear, sometimes with added apt statistics; the gauze veils to mark the different areas and hung from the ceiling had animations of medieval images which brought in some welcome movement. The artefacts available to touch and the scents of Heaven and Hell and the cosmetics, plus the recordings to listen to made this a more rounded experience for the visually impaired. The exhibition was very dark, necessary to protect the books and objects displayed, but we definitely felt in need of daylight (and coffee) afterwards. The pale blue entrance hall with its blue Perspex with thick modern lines vaguely indicating the typical medieval house, castle and church, felt more like a swimming pool entrance than an inviting opening space. Previous British Library exhibitions sometimes had spotlights on objects that would be unaffected by strong light, which made the darkness seem more dramatic in contrast. There were no handouts, except the excellent one for the visually impaired, so the handbook was very necessary to enjoy the exhibition to the full but at £25 it was possibly more than many people would wish to pay on top of the ticket cost. The silhouette area felt bleached out and stark and the bench was rather basic and uncomfortable, a pity not to end on a highpoint. When the exhibition was sold out (as it frequently was) there were bottlenecks, especially in the ‘Body and Health’ section. Yet, these are minor criticisms. We definitely, like Alice Crane, enjoyed ‘great cheer’ in the British Library’s Medieval Women, a marvellous exhibition that richly achieved its aim to narrate medieval women’s lives in their own words or in their lived experience.

Further information

This review was produced with collaboration from Dr Diane Heath, Professor Louise Wilkinson, Dr Harriet Kersey, and Dr Sheila Sweetinburgh.

The guide to the exhibition, now available, was a resource for images for this review.

Further reading:

British Library, Medieval manuscripts blog

British Library, ‘Tales of Medieval Women’, Medieval manuscripts blog

Cicero, De senectute, handwritten copy by Ippolita Maria Sforza, 1458 (Add MS 21984)

de Pizan, C, Le livre des faits d’armes et de chevalerie, 1434 (Harley MS 4605)