Misbehaving Bodies: exhibiting illness

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201402

Abstract

The essay explores the process of curating Misbehaving Bodies: Jo Spence and Oreet Ashery, an exhibition held at Wellcome Collection from May 2019 until January 2020. The exhibition brought together two artists of different generations who explored the representation of illness and care narratives from the perspectives of patient and lived experience. The project was co-curated by Bárbara Rodríguez Muñoz and George Vasey. The Wellcome Collection challenges how people think and feel about health and this essay explores how the exhibition built upon those ambitions. The text addresses how the content of the exhibition was supported by the various exhibition elements: narrative, process, architecture and design, interpretation and live programming.

How we die is how we live, only more so

Keywords

cancer care, chronic illness, Curating illness, exhibiting lived experience, Healthcare, Jo Spence, medical photography, moving image, Oreet Ashery, representation, sickness

Context

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201402/002

The Final Project (end picture, ‘Floating’), 1991–92 by Jo Spence

© The Jo Spence Memorial Archive, Ryerson University, courtesy Wellcome CollectionIn The Undying (2019) the American poet and essayist Anne Boyer writes, ‘the history of illness is not the history of medicine – it is the history of the world…’ (Boyer, 2019). Boyer’s words elegantly summarise the ways in which discussions on healthcare touch upon issues of race, class and gender politics.

The Undying is an account of Boyer’s treatment for cancer and its frank and lyrical tone invokes another great American writer’s take on the psychological and social effects of illness. Susan Sontag’s Illness as Metaphor (1978) reflects on Sontag’s cancer diagnosis, famously opening with the lines:

Everyone who is born holds dual citizenship, in the kingdom of the well and in the kingdom of the sick. Although we all prefer to use only the good passport, sooner or later each of us is obliged, at least for a spell, to identify ourselves as citizens of that other place.

This essay addresses the curating of Misbehaving Bodies: Jo Spence and Oreet Ashery, an exhibition at Wellcome Collection from May 2019 to January 2020. The show brought together the work of Jo Spence (1934–1992) and Oreet Ashery (1966–), two artists from different generations who explore the representation of illness and experiences of care.

It explores the challenges of producing an exhibition on the subject of illness and presenting conflicting patient testimonies. It goes on to interrogate the curatorial strategies that were deployed to provide a comfortable space for difficult material, and give voice to people with lived experience, healthcare providers and carers, academics and artists. Boyer and Sontag’s words frame many of the key issues that the exhibition addressed and form a roadmap to help navigate my reflections in this essay.

Production still, Revisiting Genesis, 2016, by Oreet Ashery

© Oreet AsheryCentral to Ashery and Spence’s work, and core to the exhibition, were a series of questions: How does illness disrupt and shape the way we think about the body, family and identity? What does healthy mean? As people are living longer, often with chronic illnesses, how do we live with uncertainty? What does it mean to live well with chronic conditions and illness?

While racial, class and gendered discourses touch us all in different ways, the experiences of illness and death are – as Sontag reminds us – inevitable. Sickness is a universal subject and healthcare is a nexus in which many political and social issues intersect. In a roundtable conversation published in the exhibition guidebook, Oreet Ashery states:

Death is an exaggerated form of life, so that if you are poor and you become ill you will become poorer. If you are a person who is queer, it can be difficult for people to come and visit you in hospital. The economy of marginality people experience over their lives becomes highlighted in death.

Alongside Boyer and Sontag, Ashery touches upon something crucial in the curatorial aims of Misbehaving Bodies. While illness is a universal human experience, pain and suffering are not always equally distributed. I write this essay during lockdown in the middle of the Covid-19 pandemic and these issues feel more urgent. While this is not an essay about Covid-19, Ashery’s words feel prescient. The latest data from the Office for National Statistics indicates that communities in poorer and BAME communities have been drastically more impacted by the virus (England and Wales methodology, 2020). It should come as no surprise that people who are often subject to systems of exclusion typically bear the brunt of the precarity and pain that comes with illness.

Conversations around healthcare have become amplified since the exhibition closed. One of the aims of the exhibition was to complicate the binary between health and sickness and to think of these terms as a sliding scale, rather than absolute.[1] These distinctions have further collapsed in the face of the pandemic, and in the words of the co-curator of the exhibition Bárbara Rodríguez Muñoz, ‘we are all potentially healthy and sick, carers and patients, infectious and vulnerable and overall we are all entangled’. The pandemic has made ‘an abstract reality become very tangible’ (Vasey, 2020).

‘Photo Therapy: Infantilization’, 1984, collaboration with Rosy Martin

© The Jo Spence Memorial Archive, Ryerson University, courtesy Wellcome CollectionThe title of the exhibition, Misbehaving Bodies, articulates many of the things we were hoping to achieve with the show. The etymology of the prefix ‘mis’ suggests that something has gone astray – that it deviates from the ‘normal’. The current urge to return to normality in the face of the pandemic and the ubiquity of the term ‘the new normal’ erases the voices of immunosuppressed people for which the ‘normal’[2] was often a space of exclusion and inaccessibility. We can look to projects such as the open call disability arts manifesto Not Going Back to Normal (2020),[3] as part of the advocacy work in challenging these assumptions.

‘Misbehaviour’ is something a parent would say to a child, and it captures the sense of infantilisation that many patients recognise when negotiating healthcare environments. Through this essay I will articulate the ways in which Spence and Ashery respond to feelings of disempowerment and how, through the curation of the exhibition, myself and Rodríguez Muñoz expanded on the logic of the artists’ intentions and instituted Wellcome Collection’s interdisciplinary approach to exploring and challenging how both individuals and society think and feel about health. The institutional impetus for the exhibition emerged after the Wellcome Collection acquired six Jo Spence photographs in 2015 for their Art and Healthcare collection.

According to Rodríguez Muñoz, Spence’s raw, confrontational works chimed with ‘a growing appetite for more honest, unheroic, embodied narrations of illness and overall experiences of vulnerability that challenge glossier representations of perfect, productive, healthy bodies’ (Vasey, 2020). Getting sick and the process of dying is – unsurprisingly – not a conversation people want to readily engage in but as an institution dedicated to exploring healthcare it feels crucial to be able to host this difficult conversation.

This increased appetite for narratives that challenge traditional concepts of illness and sickness is evidenced through exhibitions exploring healthcare and the political conditions of sickness and disability internationally. Examples include Nora Heidorn’s group exhibition Sick and Desiring, held at Bergen Assembly in 2019, which aimed to politicise sickness and ‘organise around shared vulnerabilities and operate against a culture which fetishises notions of health and wellness that are in the service of ever-increasing productivity’ (Heidorn, 2019).[4] The project brought together the artists Sarah Browne, Julia Bonn and Inga Zimprich among others, who ‘nurtured practices of self- and collective care’. The programme encompassed an exhibition, screenings and workshops, drawing on the history of collectivist and activist action to question the pharmaceutical industries and advocate for alternative treatments.

Similarly, terms such as vulnerability, healing, resilience, collectivity and self-care have become prevalent among institutional press releases recently[5] in what can be perceived as a healthcare turn in cultural discourse. While disability arts has a long and storied history, it has historically been ghettoised in the UK and supported by organisations dedicated to these particular practices, including SHAPE, Disability Arts Online, The Sick of the Fringe and DASH. These previously marginalised conversations and practices have — to some extent — started to gain greater visibility. Artists such as Carloyn Lazard, Leah Clements, Johanna Hevda and Simone Leigh have garnered institutional attention for work addressing sickness. Mari Katayama and Jesse Darling explore the politics and representation of disability and were both included in Ralph Rugoff’s exhibition May You Live in Interesting Times for the Venice Biennial in 2019, placing these narratives at the centre of art world attention.

Alongside this mainstreaming, there has also been a resurgent interest in the HIV/Aids activist work of David Wojnarowicz, Gran Fury and ACT UP,[6] who have received much increased attention on both sides of the Atlantic. The AIDS epidemic, in particular, showed us the ways in which activists and artists politicise sickness to challenge normative notions of healthy bodies. It is no coincidence that this resurgence has corresponded with an austerity drive across Europe and America that has eroded care capacities and public infrastructure. In a recent report by the Social Metric Commission in the UK (Measuring Poverty, 2020) they concluded that four million of those in poverty in the UK are disabled. As mentioned earlier, the retraction of welfare support continues to disproportionately affect the most vulnerable.

There has been a similar appetite in publishing with new books on the topic of disability and pathography from Robert McRuer, Anne Boyer, Frances Ryan and Dodie Bellamy reaching broader audiences beyond academia. In film-making, Crip Camp[7] (2020), which explores the civil rights histories of disability, has been met with commercial and critical success. Misbehaving Bodies happened amid this groundswell of activity that perhaps made audiences more receptive to its concerns.

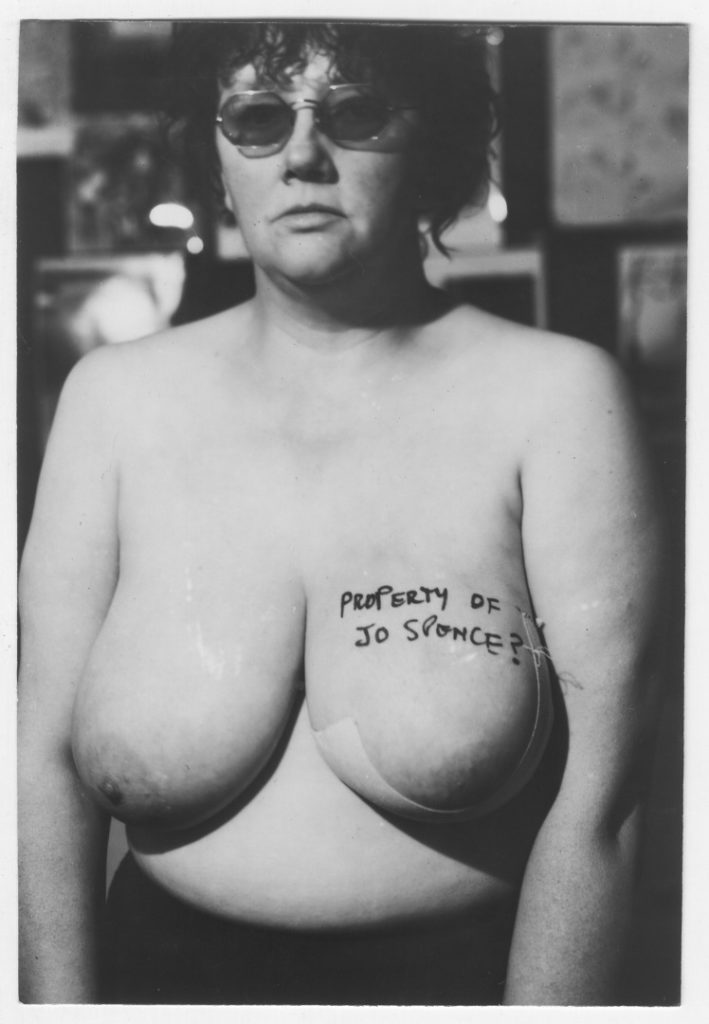

‘Crisis Project/Picture of Health? (Property of Jo Spence?)’, 1982, by Jo Spence

© The Jo Spence Memorial Archive, Ryerson University, courtesy Wellcome CollectionSpence’s work has received acclaim since the 1980s for its radical reassessment of representation and healthcare. During her life she worked across community, education, healthcare and gallery contexts.[8] Because of this itinerant practice, her archive is dispersed and fragmentary, largely split between the Ryerson University and Richard Saltoun Gallery, London.[9] Birkbeck, University of London host the open access Jo Spence Memorial Library, run by Professor Patrizia Di Bello, containing archival material and Spence’s extensive library of books on healthcare. Posthumously, Spence has had retrospectives at MACBA, Barcelona in 2005 and been included in documenta 12 in 2007, and since her retrospective at Studio Voltaire and SPACE, London in 2012 her work has gained traction, increasingly supported and acquired by institutions such as Tate and Wellcome Collection.

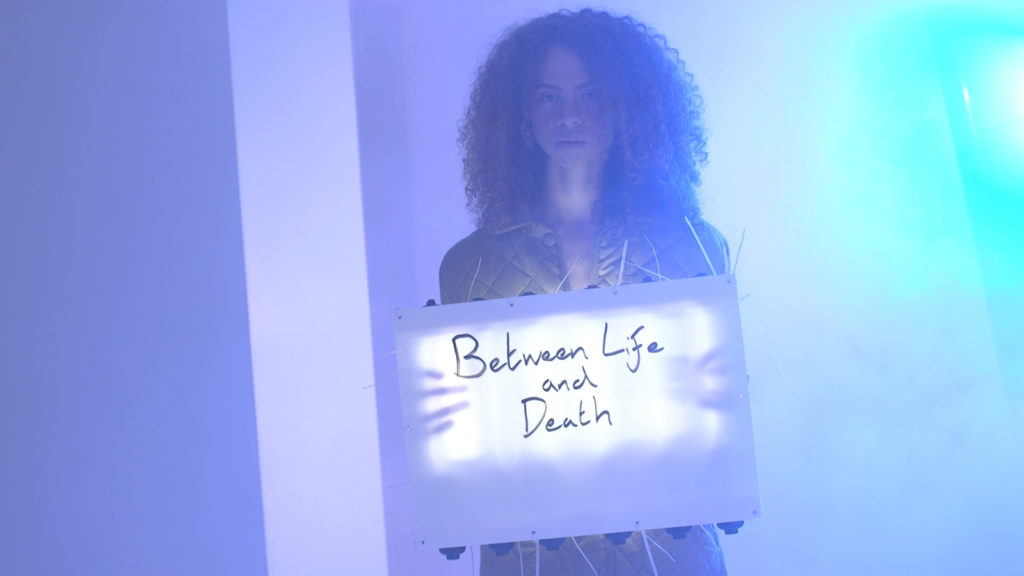

Production still, Revisiting Genesis, 2016 by Oreet Ashery

© Oreet AsheryAshery’s trans-disciplinary work has traversed performance, installation and moving image. Since the late 1980s her work has explored community and mutual care, through the lens of class, gender and sexuality. Her work has gained traction internationally over the last ten years with major commissions for Artangel in 2010 and 2013, and inclusion in Rennes Biennial in 2018 and 6th Thessaloniki Biennale of Contemporary Art in 2017. Ashery was awarded the Jarman Award in 2017 for Revisiting Genesis and Turner Prize Bursary in 2020 for her work on Misbehaving Bodies. She is currently an Associate Professor of Fine Art at Ruskin School of Fine Art.

The exhibition

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201402/003This exhibition was initiated in 2017 by Wellcome Collection curator Bárbara Rodríguez Muñoz. I began working on the exhibition as she went on maternity leave in summer 2018, coming into the exhibition having worked on the Jo Spence estate in various capacities since 2012.[10] This essay explores my curatorial involvement in Misbehaving Bodies and the institutional ambitions for the project. Most curatorial writing exists in advance of an exhibition so I am grateful for the opportunity to explore the show retrospectively and bring it to life for those that did not see it. As with any project, it is a product of many different voices and collaborative energies that bring the project to fruition, including close collaboration.[11]

For sake of clarity and deeper analysis, the essay is split into a series of mini-chapters that break the show into constituent elements. An exhibition offers a moment of making public what had previously existed as semi-private, including conversations with artists, colleagues and stakeholders. Exhibitions are spatial and experiential arguments formed through art-works, architecture, display, design, interpretation and flow and, as such, resist easy articulation in the written word.

The essay explores the Narrative of the exhibition, focusing on the choice of work by each artist. Instituting care focuses on the consultancy and support that we sought during the process of putting the exhibition together. Exhibition design explores the exhibition dramaturgy and our collaborations with David Kohn Architects and the graphic designer Mark El-Khatib. Interpretation and public programme have been folded into the same chapter as a way of thinking through the discursive framework of the exhibition holistically.

Narrative

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201402/004The exhibition explored the thematics of ageing, illness and dying from the perspective of people with lived experience. While distinct in their approach, both of the artists politicise the conditions of sickness. In doing so, their work connects to a longer history of artists who have foregrounded healthcare narratives to interrogate social inequality, including David Wojnarowicz, Hannah Wilke and Bob Flanagan to name a few. Flanagan’s work in particular politicised sickness as an artist living with cystic fibrosis. His work merged sado-masochism, bodily transgression and humour in performances that created discomfort and confrontation to challenge conceived notions of disability.

For Misbehaving Bodies, we presented an edited selection of Spence’s work from 1978 to 1992 drawn predominantly from her healthcare work made in the 1980s. Spence’s work interrogated documentary photography through the lens of gender and feminist discourse and by the early 1980s had developed a reputation for her collaborative work with the Hackney Flashers[12] and Terry Dennett.[13]

This work invariably touched upon themes of domestic and unwaged labour informed by Spence’s feminist concerns. In the late 1970s, Spence increasingly became dissatisfied with the limitations of documentary photography, turning her camera on herself. With this she developed a more performative practice to deconstruct identity and interrogate how this was formed through photography. Spence rarely called herself an artist and saw her practice as educational, typically exhibiting her work in libraries, community centres, feminist conferences and workshops as well as publishing her writing extensively. This was fairly typical at a time when there were few galleries in the UK showing overtly political and experimental work and little commercial infrastructure to support it. This strategy was both a necessity and a way to ensure that her work gained traction among academics, cultural figures and community groups that could sustain her work longer term.

Jo Spence, ‘A Picture of Health: How Do I Begin?’, 1982–83, collaboration with Rosy Martin

© The Jo Spence Memorial Archive, Ryerson University, courtesy Wellcome CollectionIn 1982, Spence was diagnosed with breast cancer. In the remaining ten years of her life her work dealt with the psychological and physical scars of this diagnosis and her subsequent treatment almost exclusively. This body of work formed the focus of our exhibition at Wellcome Collection. The only work in the exhibition that predated the cancer diagnosis was ‘Beyond the Family Album’ (1979), which articulates many of the thematic and formal strategies Spence would go on to pursue. The work takes the form of a multi-part collage over 24 laminated panels presenting an alternative family album. It marked a major shift in Spence’s practice towards an interrogative form of self-portraiture, containing biographical details typically left out of most familial archives; a picture of her face after it was burned in an accident, reflections on a divorce, and a list of chronic conditions including depression and asthma. Spence often used an unattractive raking light source to accentuate the bags under her eyes and her wrinkles. She combines imagery of anti-depressant adverts aimed at women with pages photocopied from children’s fairy tales, juxtaposing the construction of gendered fantasy with reality. Spence was particularly interested in the symbolism of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and much of her work deconstructed class and gender expectations.

‘Beyond the Family Album’ provides a framework for Spence’s subsequent concerns and a commitment to critical and self reflexive autobiography. The exhibition display then moves forward three years to ‘Cancer Shock’ (1982), made in the immediate aftermath of Spence’s cancer diagnosis. The work details the stages of diagnosis from fear and anger to acceptance. The panels contain images of Spence’s diet ‘before’ and ‘after’; exploring her addiction to sugar and her new raw juice nutritional regime. On the other side of the gallery, ‘The Picture of Health’ (1982–1986) was installed. Encompassing over sixty panels, the work was displayed in many different configurations during Spence’s life and it represents the key work in the exhibition. Made with a network of collaborators including Terry Dennett, Rosy Martin and Maggie Murray, the work narrates Spence’s diagnosis, criticisms of conventional cancer treatment and advocacy for alternative and holistic healthcare. The work is dense with text taken from newspapers on the cancer industry, Spence’s own text alongside photographic self-portraiture. There is not enough space in this essay for an in-depth analysis of the work[14] but taken collectively it forms a diary of this period, recording Spence’s thoughts and feelings post diagnosis and through her subsequent healthcare regime.

From photographs displaying post-operation scarring to critical reflections on orthodox treatment, the work is antagonistic and confrontational. It includes images from Spence’s phototherapy works, made in collaboration with Rosy Martin.[15] In these, she typically returns the gaze of the photographer who doubles as a therapist in a workshop situation and re-stages a moment of trauma through role play. Spence was clear that phototherapy was a way of ‘using photography to heal ourselves’ (Spence, 2005). Spence’s work is a form of counter-archive, foregrounding images that typically get written out of personal histories such as the family album. For her, being ill, being old, being over-weight, being working class and being a woman in a man’s world were all subjects that contributed to the economies of marginalisation that ought to render her invisible. Her work is a confrontation with this silencing, wittily deconstructing stereotypes and moving beyond representation to self definition. Spence, ‘put herself in the picture’,[16] allying the photographic image to social and political visibility.

With this exhibition Rodríguez Muñoz wanted to put Spence’s work into conversation with an artist who was currently active. A lot has changed in cancer treatment in the last thirty years and it felt important to update the conversation. Ashery was chosen from a shortlist[17] and invited to work towards a new commission that would be presented alongside Spence’s work. Over a thirty-year career, Ashery’s work had explored queerness, community and the politics of marginality. Over the last five years her work had focused on the representation of grief, dying and the politics of care. Her work Revisiting Genesis, 2016 – originally commissioned by Stanley Picker Gallery and partially funded by the Wellcome Trust – shares many similar concerns to Spence. The series similarly interrogates medical authority, placing emphasis on the voices of people with lived experience and foregrounding an holistic understanding of health, encompassing mental as well as physical health.

The 12-part series merges fictional and real life accounts from actors and friends, exploring the legacies of artists living with life-limiting illness, alongside the story of a dying artist called Genesis. For T J Demos, Revisiting Genesis ‘invites speculation about a subject – death – that was once profoundly private and subjective, but is now fully embedded in consumerist calculations, new media services, and class politics’ (Demos, 2020).

Installation view of Revisiting Genesis at Rennes Biennial, 2018

© Oreet AsheryAshery’s work probes the death industry and the commodification of grief made possible by new technology. Real nurses appear alongside actors playing carers. The script was developed in consultation with palliative care nurses and people with chronic conditions. Much of the dialogue was improvised on set. How We Die Is How We Live Only More So, a book I co-edited with Ashery, brings together the full scripts alongside newly commissioned essays and interviews (Vasey and Ashery, 2019) and acting as a reader for the work’s themes.

Production still, Revisiting Genesis, 2016 by Oreet Ashery

© Oreet AsheryThe films were originally distributed episodically online and the work has typically been displayed chronologically in cinematic environments and on single screens in galleries. Its original presentation at Stanley Picker Gallery was accompanied by beanbags for people to lounge on and a table of biscuits and tea that visitors could help themselves to. At once comfortable and clinical, the whiteness of the gallery’s walls was extended onto the floor. The whiteness here is multi-layered. The gesture is partially inspired by Syrie Maugham, an interior designer who became known for designing the first all-white rooms in the inter-war period. The whiteness evokes both clinical and contemporary art spaces and can be read as a space of exclusion and a place of discomfort. For myself at least, witnessing a near identical installation at the Les Ateliers de Rennes, 2018, the space felt purgatorial. Visitors seemed to float, with the line between floor and wall dissolved. Bodies rendered as ghosts, misbehaving bodies disobeying the laws of gravity, the gallery becoming marked by the imprint of human bodies. The references and metaphors pile up through this mode of display.

The working title for Ashery’s Wellcome Collection proposal – A Community Centre for the Undesirables – explicates these themes. Communities exclude as much they include, the gallery is articulated as a civic space for marginalised communities to convene and share their vulnerabilities. Cleanliness and contamination, conviviality and discomfort: Ashery’s work trades on these oppositional tensions.

Installation view of exhibition

© Will Pryce: www.willpryce.comMany of these ideas and conversations informed our design and interpretive approach to Misbehaving Bodies. Counter to previous presentations, we decided to change the chronology of Revisiting Genesis’ presentation as we felt that for a museum with a large footfall, a single screen would break up the flow of the exhibition space and pose a challenge to people’s attention spans. We split the episodes onto five separate themes displayed on flat screens throughout the gallery. Exhibition attendees were invited to navigate the screens in any way they wanted and the nature of the episodes, often 5–10 minutes long, invited people to dip in and out of the narrative. On the first screen[18] we follow the story of Genesis, a virtual character embodied by an iPad. Genesis is a female identified character that we never see. Her literal invisibility acts as an allegory for the invisibility of female artists from institutional collections and archives.

On the next screen[19] we explore the digital legacy of artists living with chronic conditions such as Crohn’s disease and follow the artist Bambi, played by Martin O’Brien, who has cystic fibrosis. In these episodes nurses market posthumous services such as avatars formed by harvesting social media feeds and digital slideshows stored and broadcasted to loved-ones at key moments in their life. These episodes explore the relationship between big data, digital privacy and grief. Many of the technologies were sourced through Ashery’s thorough research into new technologies emerging in the death industry.

On another screen[20] Ashery explores her personal archive of photographs. These include an episode reflecting on photographs that the artist took as a young art graduate of an M&S factory in Swindon in the mid 1990s, and reflections on Leicester Community College where she studied. Panning out from the micro-politics of friendship and personal loss, the narrative addresses issues of privatisation, community atomisation and the erosion of the welfare state.

Displayed on its own screen, ‘Episode 9: Our Nurses’ includes footage of palliative nurses on a tea break talking about the emotional toll of care work. The dialogue centres on grief and reflections of their own mortality and the cathartic importance of sharing their concerns. This screen was installed next to Spence’s ‘Cancer Shock’ (1982), with the healthcare professionals giving an alternative account to Spence’s critical patient testimony.

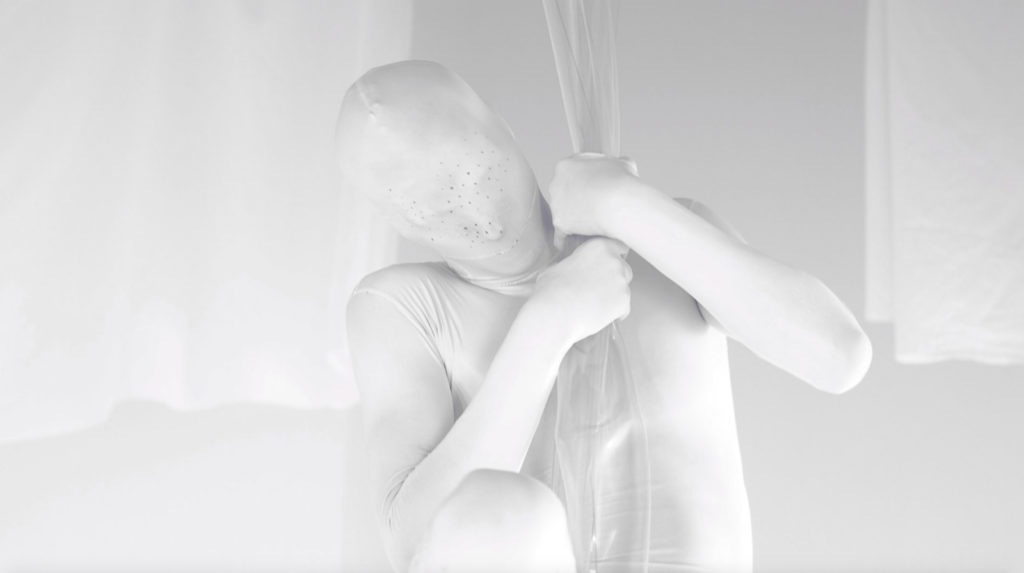

‘Episode 12: Prayer, Aerialist’ – the final work in the series – was projected onto a floating screen in the middle of the gallery. A kaddish, or Jewish prayer for the dead, written by Ashery, played from a directional speaker overhead. The work portrayed an aerialist dressed in an all-over white suit, obfuscating their face and gender. The body, hanging on to a rope, floats at a moment of dissolution with the white background. The episode, much like Spence’s The Final Project (end picture ‘Floating’) (1992) – present in the other half of the gallery – displays the act of dying in symbolic terms, the floating body in a limbo between the Earth and something de-material. Ashery’s kaddish was printed next to Spence’s photograph, further emphasising the relationship.

Installation view of Revisiting Genesis, Episode 12 in the exhibition

© Thomas Farnetti, courtesy Wellcome CollectionAshery’s new commission Dying Under Your Eyes (2019) came into the exhibition half way through its run, providing the show with a fresh impetus during its eight-month run. Ashery’s new film, much more direct than Revisiting Genesis, encompassed iPhone footage shot over the last eight years of her father’s life, edited after his death. The work extended Ashery’s interest in the representation of ageing and dying, and like Spence’s work the film is a counter-archive of the family, inverting the paternal and maternal gaze to film moments that typically remain outside the site of representation.

Instituting care

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201402/005The most anti-capitalist protest is to care for another and to care for yourself. To take the historically feminized and therefore invisible practice of nursing, nurturing, caring. To take seriously each other’s vulnerability and fragility and precarity, and to support it, to honour it; empower it. To protect each other, to enact and practice community. A radical kinship, an interdependent sociality, a politics of care.

Over the course of ten months, Misbehaving Bodies received around 166,000 visitors, a significant number for an exhibition dealing with such political work. The Wellcome Collection is a free venue situated next to University College Hospital and, as such, receives many audiences who have visited the oncology wards and waiting on loved-ones who may be using the Wellcome as a respite space. While marketed as a 14+ venue, many families and younger children also visit the galleries.

Dealing with such traumatic subject matter in a direct way, the exhibition’s content was potentially triggering material for many members of the public and much discussion ensued about Wellcome’s institutional responsibility to colleagues and the public. A budget was allocated for a programme of wellbeing during the project, devised in collaboration with the exhibition project manager Bryony Harris. Early on during my involvement we invited the cancer charity Maggie’s to act as consultants on the project following the Wellcome Collection’s collaboration on the previous project Living with Buildings (2018–19).

For an exhibition with such sensitive material, it felt crucial to seek Maggie’s advice on aspects of design and interpretation, as well as connecting us to a network of people with lived experience. Maggie’s undertook a series of workshops with Wellcome Collection staff and became sounding boards throughout the project. Maggie’s advised us to seek testimonies of healthcare professionals to speak back to the voices of patients. We approached nurses, doctors, therapists and oncology experts asking them to reflect on changes in the field during their career. These testimonies were included in the exhibition guidebook and reflected upon changes to treatment and support as well as shifts in language on cancer.

Dr Mary Burgess, a clinical psychologist from the Oncology Care Team at UCLH, was brought in to lead a wellbeing workshop for staff and various stakeholders. Burgess talked about her experience of working with people recently diagnosed with cancer who were undergoing treatment and proposed a series of self-care techniques. Martin O’Brien, a performance artist who makes work about his cystic fibrosis, delivered a talk for staff exploring his own artistic responses to illness.[21] Samaritans also led a series of workshops around active listening techniques. While these workshops and talks were never public, there was feedback from colleagues that they were valuable in creating an environment in the institution and a space outside of the delivery schedule for discussion and to air concerns. This often invisible work – caring for stakeholders and colleagues – needs capacity, time and money. Co-curating this exhibition has highlighted the need for these processes to be embedded at the outset on all projects at all institutions.

It is difficult to quantify the effectiveness of this approach but, on an anecdotal level, colleagues reflected on how the support opened up a safe space for people to talk on the subject. Most concern was voiced from the invigilation team, worried about holding conversations with upset members of the public and being surrounded by such triggering material for a long time. While Wellcome Collection’s front-of-house team are well trained and are highly qualified they are not counsellors and we worked closely with them to manage schedules so that colleagues were moved between galleries and given additional material to direct the public to resources if needed.

Exhibition design

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201402/006Health is such an odd word. How do you know every bit of you is healthy? Is freedom health? Where does mental distress fit in? Maybe healthy is just a day when you feel a bit better than bad. Once you’re over fifty good health is more of a lottery.

You can look healthy but inside you’re a mess. My daughter has an invisible disability, she can often be severely depressed but appear healthy. Health is an artificial term. It tells you nothing about a person.

Anonymised visitor comment in response to the question: ‘Do you consider yourself healthy?’

Installation view of exhibition

© Will Pryce: www.willpryce.comThe Wellcome Collection is noted for its work with architects and designers. Exhibitions have seen collaborations with Andreas Lechthaler (Joy & Tranquility, 2021), Assemble (Being Human, 2019) and Hato Press (Play Well, 2019) among others. This design-led approach helps to bridge the space between visual culture and art, medical and social history enhancing the affective resonance of the gallery space. In essence, the design aides the storytelling.

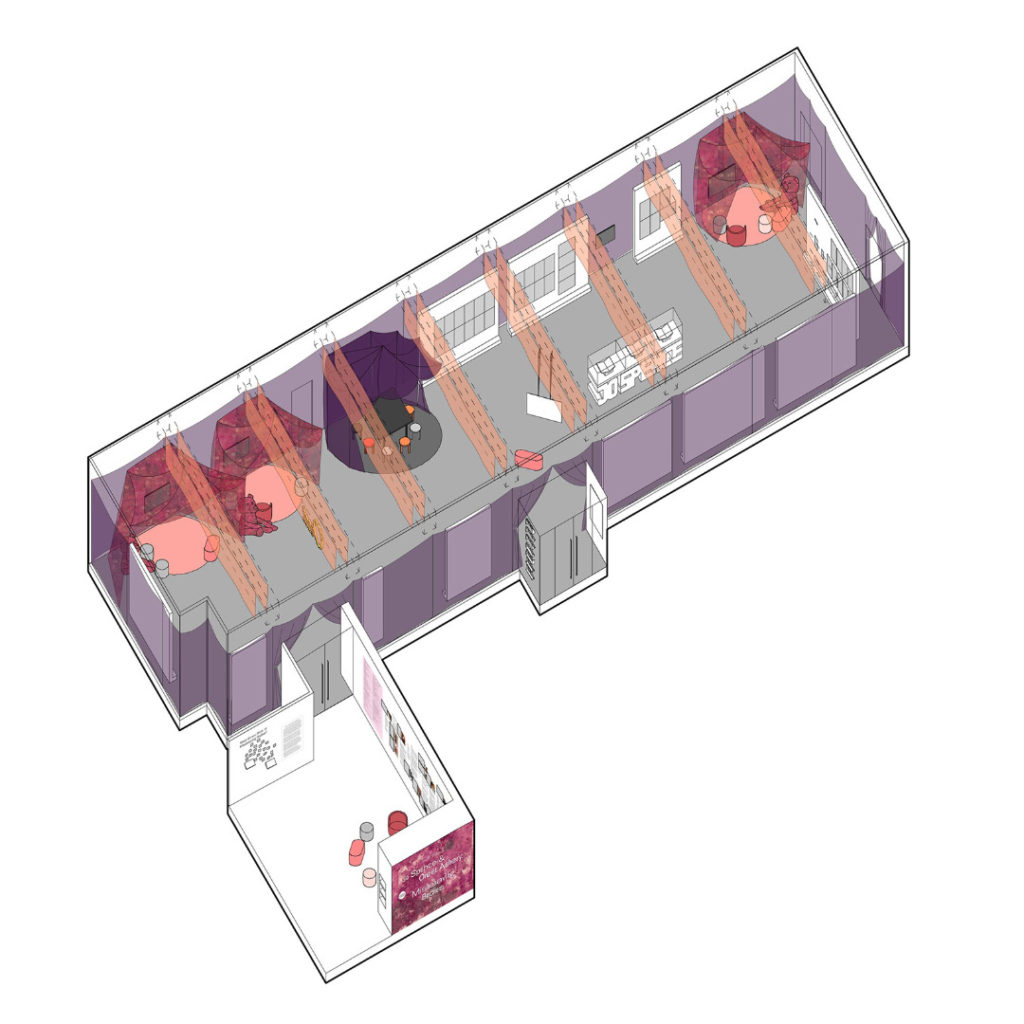

3D architectural design drawing of Misbehaving Bodies, used in the exhibition development

© David Kohn Architects/Ed ParkIn the context of Misbehaving Bodies, an exhibition with two visual artists, there is a different demand made of the design. It is a subtle but important distinction to make. The conditions for displaying contemporary art tend to differ from exhibitions on cultural artefacts and ephemera. The following quote, taken from Boris Groys’ essay The Politics of Installation, articulates the typical mode of display in a contemporary art space:

A conventional exhibition is conceived as an accumulation of art objects placed next to one another in an exhibition space to be viewed in succession. The body of the viewer in this setting remains outside of the art: art takes place in front of the viewer’s eyes – as an art object, a performance, or a film. Accordingly, the exhibition space is understood here to be an empty, neutral, public space – a symbolic property of the public.

The design of Misbehaving Bodies sat somewhere between exhibition scenography and an art installation. Viewers did not enter a neutral white cube environment but rather a space defined by the artists’ personalities. From interpretation labels that led with the artist’s voice to the presence of their names configured through gold chains and Hollywood signs, this was very much their space. By placing the frame around the threshold of the gallery rather than around the work, we wanted people to feel immersed in the work and not on the outside looking in. Once inside, the gallery was opened up with no dividing walls to provide long sight lines to the work and through the gallery. Visitors were able to take in the whole view in one go. There was no directional exhibition flow, with the impetus put onto the public to navigate in a way that made sense to them.

Installation view of Revisiting Genesis in the exhibition

© Thomas Farnetti, courtesy Wellcome CollectionThe design of the exhibition grew out of conversations between myself, Ashery, graphic designer Mark El-Khatib, David Kohn Architects and the project manager Bryony Harris. The intension with the gallery space, encompassing lots of soft fabric, warm colours and no partitioning walls, was to create a place where people felt like they were being ‘hugged’.[22] In conversation with Maggie’s, the decision was taken early on to avoid the clinical look of a typical contemporary art environment.

A design framework emerged that combined a binary stylistic approach and felt sensitive to the needs of both artists. Ashery was represented through curved, soft, warm spaces. Spence’s work was hung on hard, linear, white walls. Ashery’s screens were cocooned with tie-dye fabric that formed small den-like spaces. The tie-dye pods were made from perforated fabric, and semi-transparent so that each artist’s work could be seen through them. Spence’s work was displayed on monolithic L-shaped walls built off the wall. Spence’s scrapbook-like work has often been poorly served during her lifetime, displayed in cramped, ad-hoc spaces. Critics have tended to focus on Spence’s polemical content while ignoring how formally impactful her work can be. It felt important in this exhibition to extend the artists’ personality into the gallery and give Spence’s work lots of space. Much of my own time on the exhibition was spent editing the final object list so that the work on display was given plenty of room to breathe.

Installation view of exhibition. Foreground: Jo Spence scrapbooks with ‘name’ vitrine. Background: ‘Beyond the Family Album’ (1978–79) by Jo Spence

© Thomas Farnetti, courtesy Wellcome CollectionIn the centre of the gallery there was a flexible performance space with table and chairs that could be moved around depending on the event. This space doubled as a resource area with some contextual books and large print replicas of Spence’s dense typographic works for partially sighted visitors. It also included a box for comments in response to Ashery’s question ‘Do You Consider Yourself Healthy?’. These were anonymised and read out by actors on a number of occasions throughout the exhibition as part of the live programme. We received thousands of responses ranging from the reflective to the biographical to the critical. Exploring this material retrospectively, I’m struck by how few of the respondents – of all ages – consider themselves ‘one hundred per cent’ healthy. Themes addressed include mental and physical health, exercise, friendship, diet, disability, feelings of self worth, chronic pain and terminal illness. Taken collectively, the responses persistently seem unsure about what a ‘normal’ body and mind is. The following quote from an audience member summarises the reductionism of the word ‘healthy’:

I used to think my illness was part of my identity. I was 18 and I was a medical student. I was depression. I was my eating disorder. I LET IT BE ME. But, I’m so much more than my health. I’m 23. I’m nearly a doctor. I’m a feminist. I’m a friend. I’m a daughter. I’m a lover. Am I healthy? Am I not healthy? I’m neither. I’m alive.

Another comment puts it more succinctly:

I’m pretty healthy, for a sick person.

Installation view of Oreet Ashery’s name in the exhibition

© David Kohn Architects/Ed ParkInside the gallery, Ashery’s first name was displayed as an oversized gold chain hung from the ceiling, and a vitrine housing a small selection of Spence’s journals that formed a mini-Hollywood sign spelling out the artist’s name. The show tried to challenge many of the conventional ways of displaying contemporary art and attempted to playfully disrupt people’s expectations. It felt important – in extending the humour of the artists’ work – to make people smile. Many people came to see an exhibition about dying and encountered giant teddy bears doubling up as beanbags. The purpose of the teddy bears was both practical and conceptual. On the one hand, they formed seating for people with mobility issues, enabling different resting positions. On a conceptual level, the teddy bears signified a range of metaphors that have appeared in Ashery and Spence’s work in different guises. The idea came from Ashery, who was partially inspired by Japanese restaurants where lone diners were given large companion teddy bears. By conflating comfort with a sense for the absurd the gesture felt typical of Ashery and Spence’s work.

Installation view of Revisiting Genesis in the exhibition

© Thomas Farnetti, courtesy Wellcome CollectionThe cultural theorist Sianne Ngai has written on the cuteness of soft children’s toys as encoded as feminine and infantile, and as being closely allied to the aesthetics of violence and helplessness. Cuteness is ‘an aesthetic encounter with an exaggerated difference in power’, which ‘might provoke ugly or aggressive feelings, as well as the expected tender or maternal ones’ (Ngai, 2005). In other words, the giant tie-dye teddy bear elicited many complex, and often conflicting, emotions, much like the work of Ashery and Spence.

Speaking in a roundtable discussion, Ashery stated that “humour plays a big role in survival, and different types of humour often go with different cultural hardships” (Vasey and Ashery, 2019). Using humour as a coping mechanism and as a tool to disarm the viewer are strategies that Ashery and Spence have both deployed and the exhibition tried to amplify this logic. It is also interesting to note that the bears – or selfies with the bears – formed the majority of social media responses to the exhibition.

Interpretation and public programme

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201402/007My work is about demystifying where knowledge comes from and who possesses it.

Exhibition timeline designed by Mark El-Khatib, in the lobby

© David Kohn Architects/Ed ParkThe exhibition interpretation continually attempted to centre the artists’ experience alongside academic, cultural and lived experience perspectives. The wall labels led with artists’ quotes followed by some context written in a more neutral institutional tone underneath. Audio responses, situated on sound cones, were placed next to a number of works including further reflections. A timeline – loosely mimicking Spence’s ‘Beyond the Family Album’ – mapped Ashery and Spence’s life and work onto each other and was situated outside the gallery with pictures of the artists and their collaborations through their life. These were supplemented with reflections taken from the artists’ journals alongside quotes (that came up through discussion during the exhibition’s production) from Paul B Preciado, Audre Lorde, James Baldwin and Johanna Hedva on illness narratives.

Audio responses were sought from a range of participants, including Spence’s collaborator Rosy Martin, performance artist Marcelo Sánchez-Camus (responding to ‘The Picture of Health?’), artist Kate Davis (responding to ‘Beyond the Family Album’), and historian Elsa Richardson (responding to ‘Cancer Shock’). These audio responses added further layers of interpretation for people seeking it. If the written interpretation framed the work within the artist’s voice, the audio offered a platform that gave space for different practitioners offering multiple perspectives on the exhibition.

Richardson, a specialist in the history of nutrition, spoke on the medicinal quality of diet and the restorative quality of raw food. Richardson pondered the relationship between cooked and raw food, class and veganism, drawing historical analogies to Spence’s interest in uncooked food. Sánchez-Camus, an artist-in-residence at St Christopher’s Hospice, reflected on his work within palliative care in the context of Spence’s practice. His text reflected on the ‘liminality’ of the dying process, moving the subject from citizen to patient on a ‘hero’s journey to an unknown destination’. Rosy Martin, a frequent collaborator of Spence’s, reflected on their phototherapy work and Martin’s ongoing interest in the therapeutic quality of re-enactment photography. Kate Davis reflected on the first time she encountered ‘Beyond the Family Album’ and her own work, exploring her appropriation of Spence’s imagery to think through ideas of care work, domesticity and gender politics.

The free exhibition guidebook contained a brief curatorial introduction, a roundtable discussion with people undergoing cancer treatment and their families (hosted at Maggie’s) and a more academic conversation, resources for further information, reading list and testimonies from healthcare professionals reflecting on the question ‘What is the most significant change during your career in cancer treatment?’. From feelings of guilt (feeling like a burden) to expressions of happiness (people talked about the new friendships they had made at the hospital), the conversation at Maggie’s helped to build an holistic picture of illness narratives.

Rather than commissioning a series of essays it felt important to keep the tone conversational and foreground many voices alongside Spence and Ashery. By shifting from an institutional to more personal tone, the exhibition interpretation attempted to personalise the artists’ work and undermine institutional neutrality.

Applying this methodology to Misbehaving Bodies, we can say that Spence’s antagonism to medical orthodoxy is a fact framed by a polyphony of opinions that speak back to the work. Spence’s refusal to capture the ‘decisive’ image by working in series and recycling the same imagery in different works is reflected in the poly-vocal logic of the exhibition. Mirroring Spence’s own approach, the exhibition presented multiple perspectives rather than attempting to define a singular truth.[23]

Through the architecture and interpretation, Misbehaving Bodies replaced the certainty and clarity of linearity (people were free to move how they wanted) and institutional authority with a more personal tone (this is a story rather than the story). The layered interpretation incorporated multiple voices to foreground thematic dialogues between the bodies of work. This polyphony attempted to resist the ‘monologue of sameness’[24] that felt crucial in accounting for the conflicting healthcare testimonies.

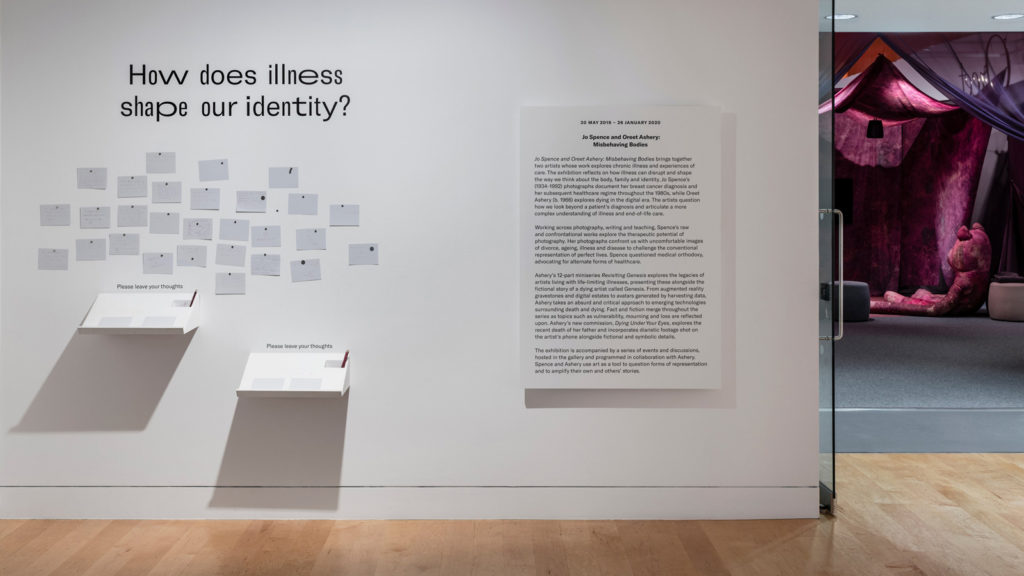

The Wellcome Trust has funded a significant amount of biomedical research, much of which Spence was critical of. It therefore felt crucial that the exhibition foregrounded the voice of the artist, creating a space for the public to reflect on how they think and feel about healthcare themselves. The introductory wall label was placed next to the visitor comments, written in response to the question ‘How does illness shape our identity?’. The question was met with thousands of comments over the duration of the exhibition with people responding with a mix of silly, poignant and heartfelt anecdotes. The placement of visitor comments next to the institutional interpretation flattened the space between the institutional tone and the voice of the public (many of whom have lived experience of the topic).

The anonymised comments varied greatly and it was clear that the exhibition challenged and divided audiences between people who felt comforted by seeing their own lived experiences reflected on the walls of the gallery and others who took issue with various aspects of the exhibition design and the artists’ approaches.

Introduction panel and visitor comments in the lobby

© David Kohn Architects/Ed ParkWhile attempts were made to contextualise Spence’s approach, comments routinely dismissed Spence’s interest in alternative medicine and felt her work was out of date.[25] On reflection, one of the main issues with the exhibition is that it required a significant amount of time and knowledge to unpack. Many visitors, of course, do not read the interpretation and some of the nuance and complexity is lost when Spence and Ashery’s work is taken at face value.

In retrospect, some of the framing of the exhibition could have been made more explicit. I have learned that exhibitions on healthcare – or any exhibition that deals with bodies and how they are made (in)visible, defined and treated – will illicit a strong emotional response. The invitation to elevate the visitor comments to such a prominent place was intended to open up a space for disagreement and it is for others to reflect on whether this was successful or not.

This interpretive baton – with visitors able to contest our own narrative – was further developed as a framework within the live programme with a prevalence of workshops and discussion groups. The programme was curated by Persilia Caton in collaboration with Oreet Ashery. These events were supplemented with screenings, talks and performances exploring themes of self-care, crip theory,[26] grief in the digital era and the continued relevance of phototherapy.[27]

Conclusion

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201402/008A number of people have said to me, “Oh you are so brave”. It’s so difficult to try and convince them that I genuinely have never felt brave. I’m terrified and “brave” is the very last thing I am. I take the treatment otherwise I die.[28]

Exhibitions are moments in time that capture a private conversation between a diverse range of stakeholders that are then made public. Discourse moves on, lives march ahead and exhibitions (hopefully) take a hold in people’s memories. Writing and reflecting on the curatorial processes is both a privilege and a cause of discomfort. In writing this essay during the middle of a lockdown with museums temporarily closed, I’m reminded of the importance of the exhibition as a space for people to congregate, converse and question their own lived experiences.

Writing her review of the exhibition in the Guardian in 2019 (Judah, 2020), Hettie Judah noted: ‘Spence and Ashery push hard against the clichés around sickness and death: dignified suffering, courageous battles, heroic legacies.’ During the pandemic, war-like and ableist rhetoric has pervaded the media. Health is persistently aligned to strength with illness defined as weakness. Ashery and Spence challenge these binaries, broadening the terms of debate and forms of representation. Importantly, Misbehaving Bodies placed these practices among other voices that spoke with the work in contradictory and supportive ways. The exhibition was about illness and dying but understood these issues to be intersectional and enveloped in issues of ageing, gender and class.

Speaking in 2016, John Berger stated that ‘it was in hell that solidarity is important, not heaven’ (Dziadosz et al, 2016). At this uncertain and difficult moment Berger’s words – alongside Ashery and Spence’s collaborative practices – feel evermore prescient.

I would like to finish with an anecdote. When I visited Misbehaving Bodies on the last day the gallery was packed with people of all ages, some with their shoes off, many lying down, some taking notes, others watching the films and many talking with their friends. It felt like more of a front room than an exhibition space – exactly as we had intended it. What started off as an exhibition about illness and dying became a project about how we live with others and find common space through mutual support. Misbehaving Bodies was a gallery as a community space, to congregate and ask questions about how to grieve and value vulnerability publicly, rejecting the binary of healthy versus sick, and the assumptions of weakness versus strength. It was an exhibition as baton, handing over the questions to the public to answer for themselves.

Tags

Footnotes

Back to text

Back to text