‘We lost a type of job for a type of person in this country’: changing expectations of working in the UK scientific civil service

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/231903

Abstract

Organisational change in UK government research establishments (GREs) during the late twentieth century profoundly affected the scientific civil servants who worked in them.[1] Civil service reforms in the 1980s and 1990s led to the reconfiguration of career management frameworks, alterations to physical working environments, the introduction of new management practices and an increasingly commercial outlook in GREs, yet we know very little about the how these changes were experienced by the scientists themselves. A new series of oral history interviews with former scientific civil servants offers the personal perspective of everyday working life in a GRE. Through extensive use of interviewees’ own words this article reveals the norms and values associated with working in the scientific civil service and articulates the processes of organisational change that led to a fundamental shift in how government scientists felt about their work. In so doing it offers a record of a type of scientific working life in the UK that has largely disappeared as a consequence of bureaucratic reform and commercialisation.

Keywords

Building Research Establishment, Defence Evaluation and Research Agency, Defence Research Agency, government research establishment, government science, life story, Oral history, organisational change, privatisation, QinetiQ, Royal Aircraft Establishment, scientific civil servant

Introduction

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/During the middle decades of the twentieth century government research establishments (GREs) and the scientists who worked in them felt secure in their status as intrinsic, valued components in both the machinery of government and wider national systems of science and innovation. However, as governments reviewed and reorganised the funding of state-sponsored scientific research during 1970–2005 GREs were subject to multiple phases of organisational change that reduced the position and influence they held in the national landscape of research and diminished the number of scientists employed as civil servants.

GREs were directly attached to government departments and operated within the frameworks of the civil service. Policies of civil service reform initiated by the Conservative Governments of the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s and sustained by the Labour Governments which succeeded them directly impacted the specialist class of scientific civil servants. The civil service staff cuts and reforms that occurred during the 1970s and 1980s had a profound effect on them as the familiar physical environments and workplace norms which underpinned working life in a GRE were disrupted and refashioned. A stark indicator of this change is the difference in staffing; the number of scientific civil servants working for government departments had hovered around 18,000 during the period 1967‒80, but by 1997 the official figure had fallen to around 7,300 (Civil Service Department, 1980; Department of Trade and Industry, 1999).

The bureaucratic reform agenda in GREs involved programmes of rationalisation at establishment level that led to amalgamations and closures while changes to the operating frameworks within the establishments saw the internal structures rearranged to accommodate commercial operations. Scientific research programmes were increasingly managed along commercial lines, and in some cases GREs were transferred from the public to the private sector. In the defence GREs, the implementation of these policies coincided with reduced spending on defence research and development (R&D) as the Cold War came to an end in the late 1980s.

Andrew Smith has pointed out ‘a noticeable gap in the existing literature on civil service culture change, where the experiences of those on the shop floor are largely absent’ (Smith, 2006). Studies have looked at the impact of similar processes of change in the nationalised water and rail industries but until now the effects of civil service reform on the ordinary men and women working in GREs have not been examined by historians.[2] Indeed, there has been limited academic study of the lived experiences of scientific civil servants. Sally Horrocks’ and Thomas Lean’s exploration of the culture of government science is a notable exception, showing the influence of the Second World War on blending notions of public service with the ethos of professional scientists (Horrocks and Lean, 2006).

This lack of scholarly interest in the individuals working in government science can partly be explained by academics’ focus on academic science, articulated by Steven Shapin thus: ‘So far as the great majority of historians, sociologists, and philosophers are concerned, science stops being science—and places itself largely outside their domain of interest—precisely when it becomes embedded in the modern institutions of government, production, and, to a lesser extent, war’ (Shapin, 2016). His assessment resonates with an earlier comment from David Edgerton that ‘our knowledge of scientists pursuing careers in industry and in government is very limited’, while more recently Paul Lucier has noted that commercial science does not ‘fit within the dominant narratives being constructed by historians of science or historians of technology’ (Edgerton, 2012; Lucier, 2016).

A new series of oral history interviews with former UK government scientists allows us to explore what it meant to work in a GRE as a scientific civil servant and how specific elements of organisational change proved incompatible with the existing workplace culture.[3] Their experiences serve as a case study that illuminates the impact of the shifting contours of knowledge production in the late twentieth century, characterised by what Gibbons et al. identified as the emergence of new criteria which would ‘determine what shall count as significant problems, who shall be allowed to practise science and what constitutes good science’ (Gibbons, 1994). In his study of the working lives of industrial scientists in the USA, Shapin set out to ‘retrieve from the frontlines of present-day technoscientific knowledge-making something of what it feels like to those trying to make a career, to make knowledge, and to make sense of the increasingly uncertain institutional worlds they inhabit’ (Shapin, 2008). The experiences remembered in these life story interviews show that the institutional world inhabited by scientific civil servants also became increasingly uncertain as organisational change and commercialisation progressed during the period 1970–2005.

Ronald E Doel has pointed out that oral history interviews offer valuable insights into ‘hierarchical relationships between individuals in complex bureaucratic organizations, and the traditionally invisible members of scientific communities: women, minorities, engineers, and technicians’. This has been demonstrated in J M Hartley and E M Tansey’s use of interviews to explore the work of laboratory technicians (Hartley and Tansey, 2015). Rob Perks similarly observes that recording memories of working life sheds light on the aspects of organisational culture that are not the stuff of written records, such as ‘the minutiae of repetitive daily routine and everyday practice’, while encouraging more junior staff ‘to reflect on the impact of decisions made further up the management structure’ (Perks, 2010).

This article examines the distinct working environment of the scientific civil service through the words of men and women employed in two of those GREs, the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) at Farnborough and the Building Research Establishment (BRE) at Watford. More than 6000 scientists worked for MOD in the defence GREs, of which RAE was one, being described as ‘the largest research and development establishment in Europe’ (Civil Service Department, 1980; Ministry of Defence, 1982). RAE’s origins lay in the Balloon Factory that carried out development work on military balloons, kites and airships at Farnborough in the very early twentieth century (Walker, 1971; Ministry of Defence, 1984). An MOD publicity brochure produced during the mid-1980s highlights the breadth of RAE’s activities in aerodynamics research, the advancement of aircraft and missile systems such as flight control, information display and the man/machine interface, and its work on developing highly-accurate instrumentation for its testing programmes. Other major areas of work covered research into materials and structures, radio and navigation, and weapons systems (Ministry of Defence, 1984). RAE was also renowned for its specialised, often unique, experimental facilities.

It was this organisation that was amalgamated with the other defence GREs in 1991 to create an executive agency, the Defence Research Agency (DRA), which became the Defence Evaluation and Research Agency (DERA) in 1995. When DERA was split in 2001, approximately 75 per cent of its staff transferred into the private sector with the formation of QinetiQ. The remainder continued working as civil servants for the newly created Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (Dstl).[4]

BRE was a smaller operation, employing approximately 500 scientists on research programmes designed to improve methods and materials used in the construction industry. Programmes encompassed geotechnics (previously known as soil mechanics), structural and civil engineering and the physics of buildings such as heating, acoustics, ventilation and lighting (Lea, 1971). BRE was formed in 1972 by amalgamating the Building Research Station (BRS), the Fire Research Station (FRS) and the Forest Products Research Laboratory (FPRL). It became an executive agency in 1990 and was was privatised through a management-led process which resulted in its being owned by a non-profit trust (BRE Group, 2021; Jenkins et al, 1988).

The scientists interviewed – 14 men and five women – had studied natural sciences, physics, physics with electronics, chemistry, materials science, mechanical sciences, applied science, engineering, and botany and zoology.[5] Some had risen to senior leadership roles and many had held substantial management roles. Two became high-ranking technical experts, while another three also became technical leaders in their research areas. Two moved into roles in central government where they were responsible for allocating research funding. A few had worked in industry before joining the civil service and one had worked in a GRE as a military liaison officer.

I identified potential interviewees by noting names of scientists mentioned in company literature, archival documents and Who’s Who, networking at events held by relevant organisations and asking for recommendations from the archival teams at Farnborough Air Sciences Trust and BRE. Once I began recruiting participants, they in turn suggested the names of other potential interviewees in a snowball effect. Interviews with a group of this size offered a range of experiences rather than a representative sample, substantiating Bruno Latour’s observation that ‘depending on which scientist is followed, completely different pictures of technoscience will appear’ (Latour, 1987). In the telling of their life stories, interviewees were at liberty to choose which version to share, and at times behaved in a similar fashion to people interviewed by Thomas Lean about the electricity supply industry: ‘few tell anything like a straightforward story, confusing dates, motives, the order of events and presenting inconsistent interpretations’ (Lean, 2018). I was conscious that most interviewees would have signed the Official Secrets Act, prohibiting them even in retirement from talking about some aspects of their work. Those that were still working would have been mindful to observe commercial confidentiality.

Their life story interviews offer insights into the everyday and personal nature of working life which public records or corporate literature do not document, while filling in some of the gaps created when the written records of changing organisations also moved from the public domain into private ownership. Interviewee reflections on career prospects, reward systems, relationships with internal and external colleagues and the working environment reveal the various elements that combined to create a marked culture in GREs. This article foregrounds their words to present a portrait of working life that gave scientific civil servants their professional identities, bringing into focus how organisational change represented a fundamental challenge to the values and norms associated with that working life.

A career in the scientific civil service

Government research establishments (GREs) were varied sites of knowledge generation that spanned many scientific disciplines. A 1982 review counted more than seventy R&D establishments which varied in size and function, from vast research establishments that employed thousands to modest agricultural field stations or niche testing facilities with a handful of staff (Cabinet Office, 1982). This quotation about defence research from interviewee Sarah Herbert gives a sense of the complexity: ‘Initially there were a whole series of research establishments across the country. [Farnborough] was the research establishment for aerospace and some weapons capability…the one at Holton Heath was all related to sea vessels…Rosyth was all to do with submarines, Fort Halstead was all to do with various weapons and guns and things like that, Christchurch was all to do with tanks.’[6]

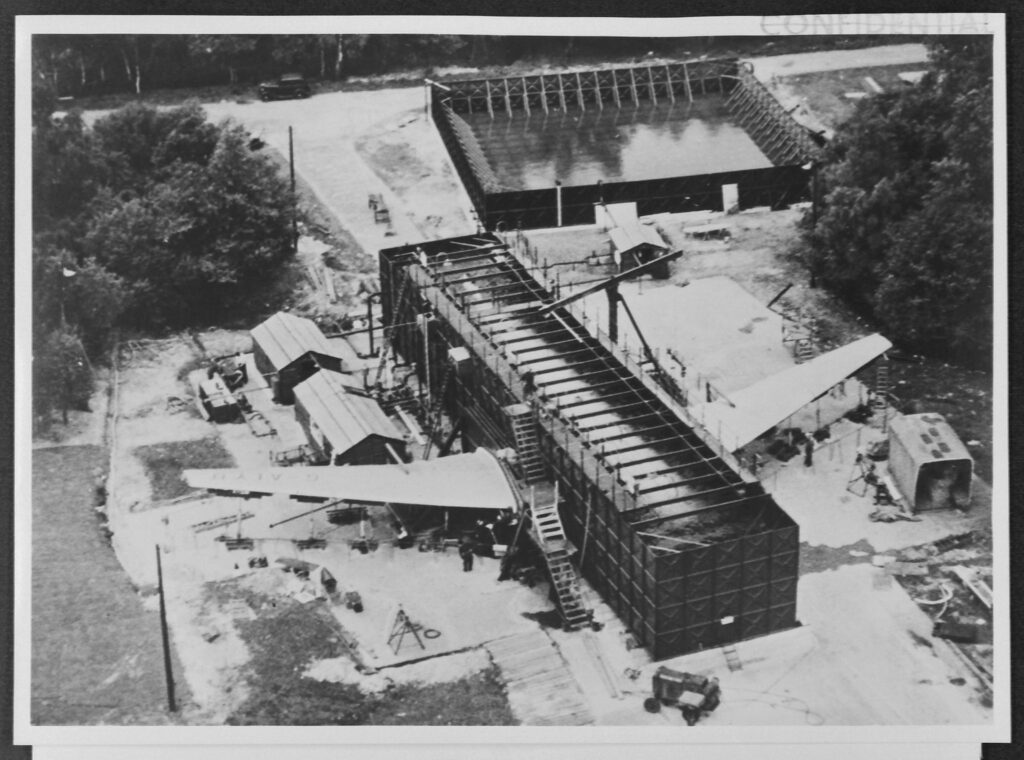

Ian Linsdell was astonished by what he found when moved from the Ministry of Defence headquarters in London to work as an accountant on site at the Royal Armament Research and Development Establishment [RARDE] at Fort Halstead in Kent: ‘It’s one thing seeing things on paper, it’s another thing entirely to see them in the flesh as it were. I had no concept of the scale of the operation – the number of people and quite frankly of the brains of the people or what they did. I had no idea at that stage what they did – which was how it was supposed to be – or just how vast the place was [with] satellite areas. […] Like a whole community, you’re talking hundreds of people, vast bits of real estate. So you then start to explore the government research establishments and you find that the ARE [Admiralty Research Establishment] has these magnificent facilities all over the place, ocean basin towing tanks where they test hulls. Similar things on the airside…to find that [at Farnborough] that’s actually the largest wind tunnel in Europe.’[7]

GREs were populated by scientific civil servants who were occupied on a fluid range of activities spanning pure science and applied R&D to testing and evaluation. The demands of the Second World War for technical expertise and innovation had cemented the position of government scientists and engineers as vital contributors to national technological advancement and the provision of expert advice (Edgerton, 2006; Gummett, 1980). After the war ended, joining the scientific civil service was recognised as a respectable way to pursue a technical or scientific career in the UK, and in the immediate post-war period had the added advantage of being a substitute for National Service. While only a relatively small percentage of science and engineering graduates went into the scientific civil service (for example in 1976 the estimate was around five per cent), they, along with non-graduate entrants, could expect a secure career with well-defined routes of progression (Civil Service Department, 1980). Many did a ‘tour’ in departmental headquarters in Whitehall, and some were drafted into a scientific unit within the armed services or in an embassy overseas as a scientific counsellor.

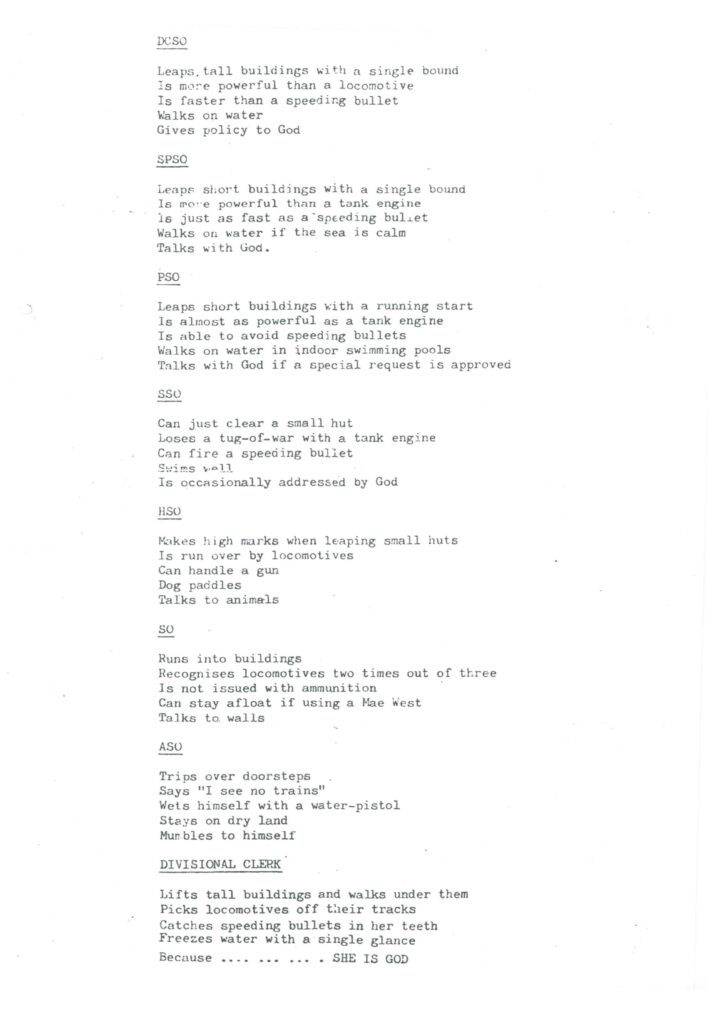

At the start of the 1980s about 35,000 staff worked in those GREs, of whom approximately 18,000 belonged to the scientific classes of the scientific civil service (Cabinet Office, 1982; Civil Service Department, 1980). Joining the civil service was to enter a bureaucracy, a closed system defined by regularised promotion, a bias towards recruiting early in life and lack of competition from external candidates. The scientific civil service was one of a number of vertical specialist streams that operated in parallel with the main bulk of the wider civil service, the administrative stream. These streams were divided horizontally into different grades, with civil servants climbing up the ladder of their stream until they reached the open structure level. Above that lay the very top tier of civil servants who were in charge of running government departments.

In the twenty years after the Second World War the scientific civil service consisted of scientific officers, experimental officers and scientific assistants (HM Treasury, 1945). Experimental officers assisted the scientific officers, while the scientific assistants were employed in the preparation of materials and apparatus, undertaking observations and running calculations. The higher grades of scientific officers were responsible for the direction and administration of the scientific work. Reviews of the organisation of state-funded science and the civil service during the 1960s led to adjustments to the grading system resulting in the grades that first delineated interviewees’ working lives (Office of the Minister for Science, 1961; Trend, 1963; HM Treasury, 1965; Civil Service Commission, 1968).

Many such as David Dunford joined as an assistant scientific officer (ASO), with a clear path ahead to scientific officer (SO), higher scientific officer (HSO), principal scientific officer (PSO) and senior principal scientific officer (SPSO). Above that lay deputy chief scientific officer (DCSO), chief scientific officer (CSO), before reaching Under Secretary in the open structure level (Civil Service Department, 1980).

While Mike Westby commented on the system making everyone ‘dreadfully grade-conscious’,[8] Susan James appreciated well-defined structures that offered the prospect of job security and steady career progression: ‘I liked it…on the promotion side, you knew there was ASO, SO, HSO, SSO, PSO and that there were pay increments in between…so you could project, you knew when you needed to start thinking about promotion and what you needed to do to get to the next level. […] There was what I called a career structure, you knew what you had to do to get to the next stage. You didn’t have to, but if you wanted to climb the ladder it was very clear what you needed to do.’[9]

Paul Cannon described his first impressions of the GRE environment he encountered when he began working as a scientific civil servant at RAE in 1981: ‘A red brick building, pretty tatty, painted in typical civil service colours; I always claim you can tell a civil service building no matter where you are in the world, there’s a kind of feeling about and smell about it. Pretty solid building with some nice labs, lots and lots and lots of equipment, some of it old and should have been thrown out, some of it only used once a year because that was the nature of it as a piece of test equipment. […] There was a Division Leader with a secretary, and vast amounts of paper being moved around. […] Offices for all the PSOs on their own, if you were an SSO or below then you might share, but [they] tended to be big offices. […] And there were technicians. […] The people were friendly, there was a relaxed atmosphere, I knew who my boss was, I knew who my boss’s boss was and that’s really important to actually know where the chain of command lies. It was all so well defined. The building was pretty knocked around, it was an immediate post-war building, but everybody made me very welcome and I was very happy. […] I loved it. […] It was a gift from heaven as far as I was concerned.’[10]

However, the attraction of a career in the scientific civil service was not just about the security offered by the civil service framework but the idea of public service, as Mike Westby explained: ‘I think what draws most people – it sounds a bit pretentious really – is doing something which is nationally worthwhile, not just making money for some shareholders. Most of the work is technically very interesting and in many ways we have more freedom of action than you would have in industry because we’re not always looking at the bottom line which makes a profit. That’s not what we’re there for and that’s quite liberating in many ways. A lot of people find that very attractive, it’s not the secrecy element, it’s that we can do technically interesting work. For quite a lot of people it’s like working in a university but probably with more stability and security.[11]

Audio 1 : Anthony Bravery on changing attitudes to public service (image credit: Bill Knight) © British Library https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/231903/010

For school leavers who were looking for an opening to put their secondary science education into practice, joining a GRE offered opportunities on both the practical and educational fronts. This story from David Dunford describes how he came to join the RAE as a teenager: ‘I didn’t plan to leave school at 16, I had started my A levels [but] my father said, “If you don’t get the grades, you need to have a job.” So I applied for a job at Larkhill[12] as an Assistant Scientific Officer [and] the scientific training officer for the RAE, Jerry Lewis, was one of the panel. […] At the end of September I had a letter saying…we’d like to invite you to Farnborough and offer you a job. […] In the letter they were very careful, they offered you education by day release, they offered you the engineering training via support from the local technical college. […] I thought actually perhaps this is an opportunity, I wanted to do more practical work and to do those sorts of things, so I said yes, aged 16¾. […] The hands-on bit, I think that was the back of the decision that I would begin to play with science. You know I wouldn’t have to go through this academic route, I could go and do it. I could practically go and do it.’[13]

For others, it was the promise of an interesting and varied working life, as Vic Crisp observed: ‘Despite the rigidity of the hierarchy and so on we did do a lot of interesting things that were…self-generated. You were doing things that you thought were important…we got to fairly high levels in the scientific community – interesting conferences and interesting places to go so there were lots of plusses on that side. […] Some people will always go for the financial reward, but there are plenty of others who are very bright who weren’t driven by money, they would want to do interesting things.’[14]

Doing interesting things

The network of GREs were themselves a small cog in the civil service machine with a common purpose of finding solutions to government’s scientific problems. Scientific civil servants in the GREs worked across a spectrum of technical activities, as this statement in the 1965 review indicated: ‘One of its most striking features is the great variety of the work, which ranges from basic research on the one hand to prototype manufacture on the other. Basic research is an essential element of this total effort. It contributes to the formulation of national scientific policy; it makes possible the establishment of reference standards, and provides basic knowledge required in the public sector as well as for the solution of problems in industry. Moreover, in the defence field security considerations make it necessary for certain basic research to be done within rather than outside the Government service. Nevertheless, the emphasis…is heavily on applied research and development projects’ (HM Treasury, 1965).

The specific details of interviewees’ work is not the focus here. Indeed, some of the projects on which interviewees worked remain beyond the public domain due to their sensitivity. What the interview material highlights is the routine and social nature of scientists’ working lives, the everyday tasks and interactions that underpinned the conduct of research in which they acted as both producers and conduits of knowledge. GRE scientists were as likely to be looking down microscopes as engaging with policymakers in oak-panelled offices in London, to be conducting field trials on the national peripheries as travelling the world to network with international peers, to be designing or building prototype technologies in workshops as taking stock of supplies or wiping down the lab bench, to be checking a departmental budget as writing a conference paper.

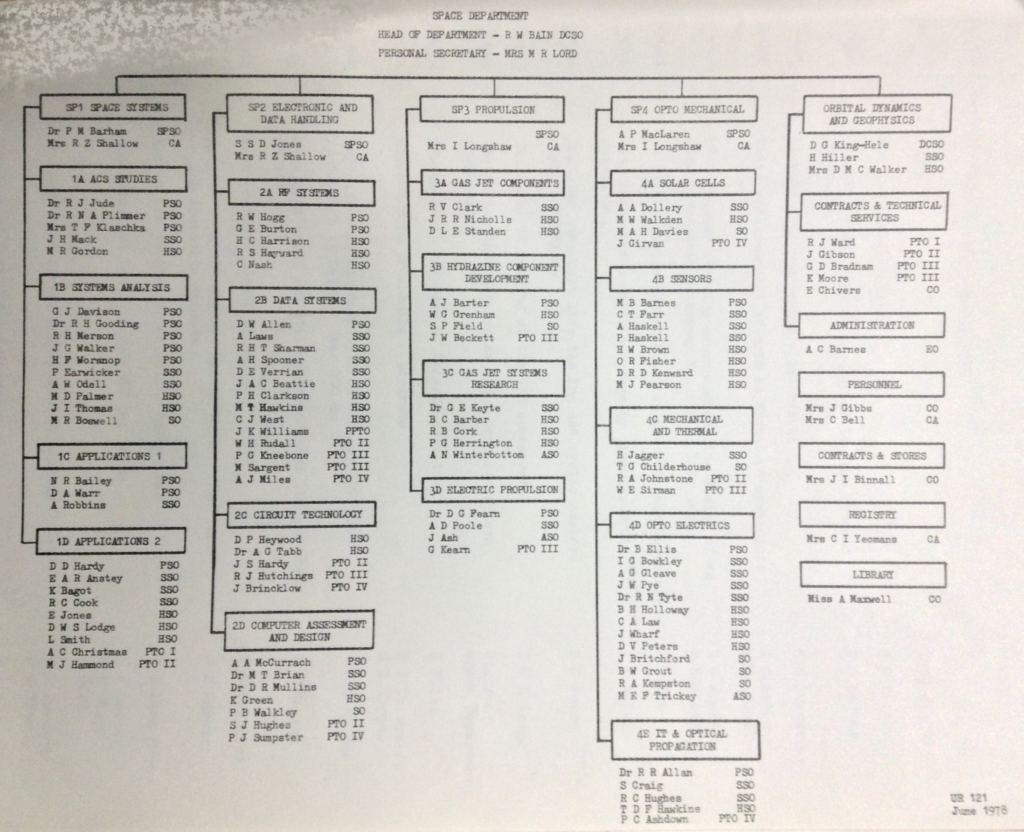

GRE scientists embodied Latour’s understanding of scientists’ work as both a social and scientific activity that is undertaken by a range of people with different skill sets (Latour, 1987). Shirley Jenkins’s description hints at the range of roles in her section at RAE when she joined as a school leaver in the 1960s. ‘I was a scientific assistant, I was the lowest of the staff people, there were industrials who were doing the mechanical things, working and we had cleaners of course […] but mostly in our area it was nearly all scientific staff. […] The boss was an SPSO…there seemed to be a few other sort of PSOs and SSOs who were doing more mathematical stuff, the sort of scientific side of it, whereas the labs were building and testing things. In the labs there were mostly experimental officers, assistant experimental officers […] the scientists they lived in offices, they didn’t come into the labs very often as far as I can remember.’[15]

For Anthony Bravery, the Forest Products Research Laboratory (FPRL) was not what he expected when he joined in 1965: ‘A slight feeling of…surprise that it would look all rather industrial considering it was calling itself a research institute. […] Of course I hadn’t thought through the fact that of course they would have workshops and machine shops, it wasn’t all laboratories…to see the big structural engineering lab where they broke beams and so on was interesting.’[16]

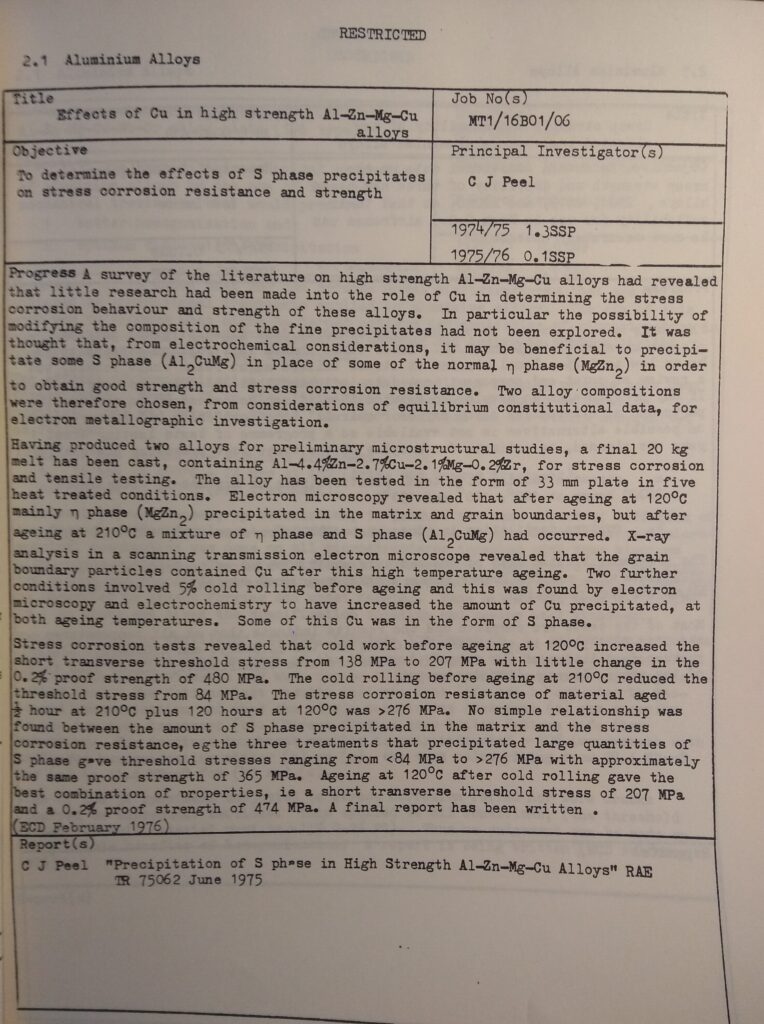

Chris Peel’s comment adds to this picture of the industrial nature of research: ‘Yeah, it was hands on stuff, we would pour molten metal ourselves, we would forge and roll ourselves, using rolling mills, forging presses, we were well-equipped, and [had] the staff. We had a selection of experimental workers and assistant scientific officers and what have you who would support the activity, but the scientific staff pitched in and did a fair bit of the practical stuff. Even quite senior people doing practical stuff.’[17]

Interviewees were very likely to be using a portfolio of capabilities that included high levels of theoretical knowledge and practical engineering skills combined with individual creativity and a can-do attitude (Sismondo, 2003). This excerpt from Sarah Herbert’s interview illustrates how she developed that combination of skills after joining RAE in 1971 soon after finishing her PhD.

Audio 2 : Sarah Herbert, former scientific civil servant and materials scientist, reflects on the similarities between working with composite materials and dressmaking (image credit: Bill Knight) © British Library https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/231903/012

Interviewees spoke about observation as a fundamental element of their work, as was the recording of those observations and writing up the results.

Latour refers to this central aspect of a scientist’s work as inscription, and interviewees such as Anthony Bravery spoke about the centrality of writing to the progress and satisfactory completion of their work (Latour, 1987). ‘Usually you start by writing a proposal, the experiments you’re going to carry out, and that’s probably something, even if you’re not getting approval for it, you’re getting reinforcement, reassurance, you have it reviewed. What you’re going to try and aim to do, title, objective, method, how you’re going to carry it out, what equipment you’re going to need, and what data you’re going to gather. […] Then you’re recording your results so that’s writing or recording in some way, and then it’s reporting, because you want to place it all on record for your own use, never mind anybody else’s. Then if you’re going to publish it goes a stage further, so in the middle of all that you’re actually filling test tubes or weighing things or pouring things or cutting and chopping and what have you, so there are practical experimental operations going on, but it’s all still being recorded. […] It’s [the same] in the field, all the material’s out there but in their hand is a notebook and they’re recording the results ready to write them up.’[18]

Interviewees refer to wider connections beyond the GREs with partners in universities and industry. The departmental funding arrangements usually required that a proportion of the establishment’s funding allocation be spent extramurally, often resulting in sponsorship of university PhD students working on projects relevant to GRE research programmes. Robyn Thorogood was one of those students, funded by the MOD to investigate the steering of vehicles through clay at Nottingham University.[19] GRE scientists also worked closely with peers in industry as public procurement programmes progressed from experimental or development stages in the public sector into production in the private sector. Government researchers would also advise industry on solutions to common problems and recommendations for best practice, while peers in industry, academia and the research associations would be consulted over the design of GRE research programmes.[20]

Interviewees describe these working relationships as incredibly stimulating, acting as pathways in a complex exchange network through which knowledge was transferred between the various public sector and industrial R&D communities. Each interaction served as a node in a web of knowledge communication, sometimes through formal written delivery such as journal articles or technical reports, sometimes through personal attendance at official meetings or giving conference presentations.

Steve Rooks remarked on how experts would get to know each other by working in the same field: ‘Through things like our NATO groups and projects that industry were involved with you got to know these people, whether they were BAe Systems or Rolls Royce or universities, or SMEs or MBDA [a missile systems manufacturer]. So you knew who the people were, so there was probably a little bit of poaching because you’d have a world expert in DRA who might retire but there would somebody in BAe Systems who was also using the same software or whatever, so it would be natural to say, “Do you want to come and work in government for a bit?”’[21] Comments such as these confirm the findings of other studies which demonstrate the role of state-funded science in developing military capability, and the juxtaposition of academia, industry and government into a triple helix structure of research and innovation (Edgerton, 2006; Epstein, 2014; Etzkowitz and Leydesdorff, 2000).[22]

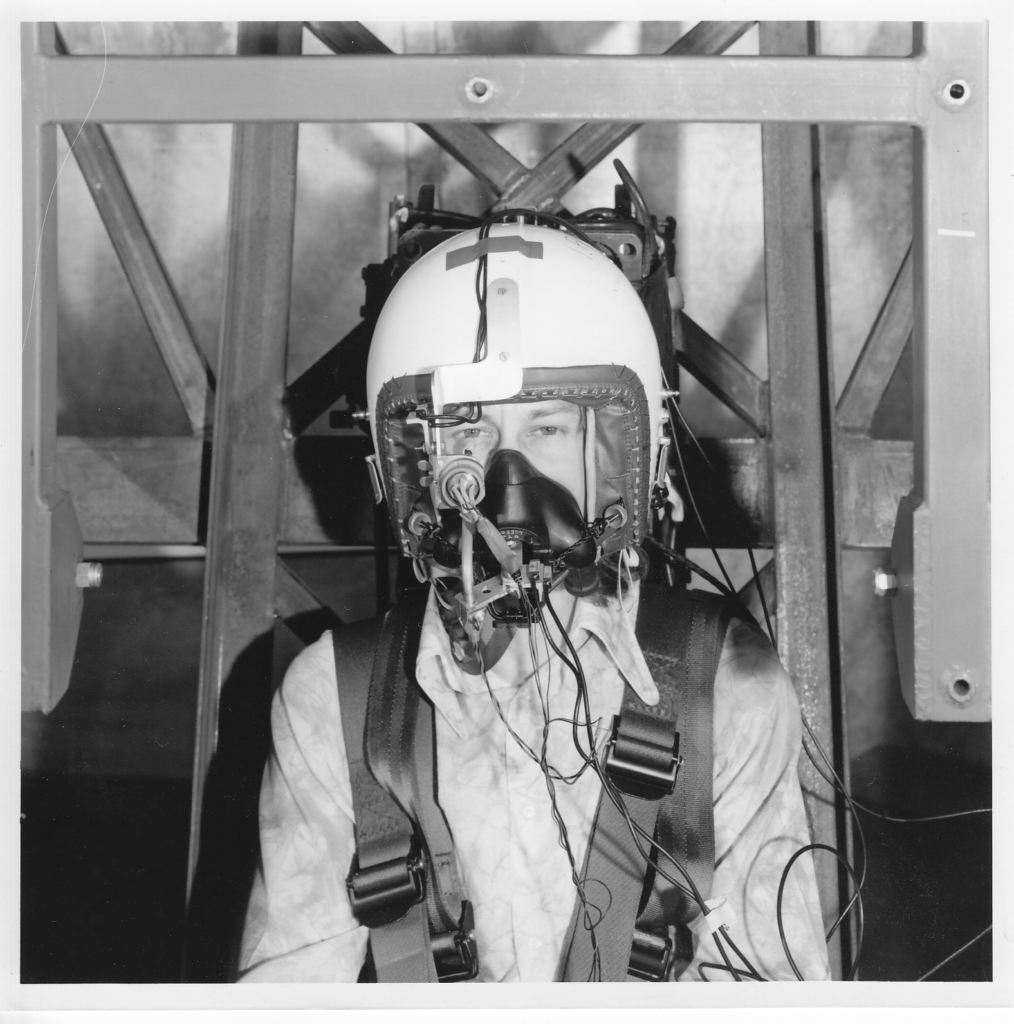

Work was regularly conducted beyond the office and laboratory space and often experienced as exhilarating, such as when Phil Catling was conducting trials for new technologies to add to pilots’ helmets: ‘When I was in the weapons group there was work there to do with weapon aiming from Canberra aircraft with very early prototype helmet mounted display, little CRT mounted on the side of the pilot’s helmet and a little TV camera in the front of the aeroplane. I’d go off to various disused airfields with my boss and we’d have to blow up tanks, not blow, blow them up, but inflatable tanks. So they were there, arrange them in certain orientations for aircraft to fly in and people would analyse the results afterwards, so exciting times.’[23]

Steve Rooks also recognised the sense of adventure associated with a job in government science: ‘The excitement of the work, let’s not take that away, because it is incredibly exciting in most areas of work. The people they get to work with, the places they go, then the ability to work with so many different organisations. One day you could be working with the best of the best in industry, the next day you could be briefing to people overseas at a conference, so amazing opportunities like that.’[24] Interviewee Chris Peel spoke about the attraction of forging many different types of working relationships with internal colleagues, researchers in other GREs, administrators in Whitehall, industrial and academic partners and international peers (Whelan, 2000).

Audio 3: Chris Peel, former scientific civil servant and materials scientist, reflects on the range of people he collaborated with in his role in a government research establishment (image credit: Bill Knight) (image credit: Bill Knight) © British Library https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/231903/017

There was a strong sense of camaraderie between the scientific civil servants in the GREs and their peers in Whitehall, as Paul Cannon remembered: ‘We used to have major field reviews as they were called, that would be led by the division leader and even by the departmental head, with help from the section leaders. […] There was so much to-ing and fro-ing of staff from the research establishments into Whitehall, so the science teams in Whitehall […] the people had nearly all worked in the research establishments. […] People were colleagues but they were friends so there was good camaraderie between the two.’[25]

That camaraderie permeated internal working relationships and the informal processes of knowledge exchange. A key fixture in the absorption of tacit knowledge – what Collins describes as ‘knowledge that is not explicated’ – were the coffee and tea breaks that brought team members together (Collins, 2010). These were remembered by most interviewees as ‘very important networking opportunities’, as this clip from David Dunford outlines.

Audio 4 : David Dunford, former scientific civil servant and materials scientist, reflects on the importance of social encounters with colleagues for the transfer of knowledge (image credit: Bill Knight) © British Library https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/231903/019

However, Dunford’s memory of those sessions with colleagues in the materials and structures department leaves out a salient feature of the GRE working environment illustrated in this photograph of the department – its dominance by men; the experiences of being a woman scientist in the scientific civil service is explored in this online article (Ledgerwood, 2021).

The features of this working environment described here combined to create a particular workplace culture, shaped and sustained by the expectations of both government and scientists about how and why government science should be carried out.

The culture of government science

During the period when the majority of these interviewees joined the scientific civil service, the civil service career frameworks and funding arrangements of GREs differentiated them from other public sector research organisations, university departments or industrial R&D laboratories. Interviewees’ accounts show how a particular combination of expectations and reward systems encouraged coherence in staff values and outlooks. Job security, special promotion paths, an emphasis on academic publication and opportunities for further education created a culture throughout the GREs which valued the development of deep, specialist knowledge.

Ferlie et al. have noted that ‘one distinctive feature of public sector organizations is that they are highly professionalized. Public service values combine therefore with the values and standards of the professions to create a complex pattern of influences’ (Ferlie, 1996). Mody has described the institutions of professional science as helping scientists to ‘pursue esoteric topics and to pronounce on public matters’ thereby manufacturing ‘a reputation for objectivity and autonomy’ (Mody, 2016).[26] In a 1956 review of the scientific civil service, McCrensky observed members distinguishing themselves ‘as a separate corps with their own leadership. This enhances their morale and prestige’ (McCrensky, 1956). An intrinsic feature of this corps was the idea that scientific civil servants would be free to operate as professional scientists, exhibiting similar expectations of a career in science as those who worked in academia.

Professional scientists, as managers and researchers, were the backbone of the GREs whose outlook was determined by the civil service hierarchies and a public service ethos. Consequently their values permeated all levels of the GREs. They valued the ability to operate autonomously, to publish in peer-reviewed journals and to share knowledge with colleagues in the wider scientific community, often as members of professional membership associations or learned societies. While interviewees acknowledged that there were aspects of the civil service bureaucracy which needed reform, they relished the freedom they experienced in the working environment. These notions of public service and professionalism meant that many scientific civil servants prided themselves on adhering to an ethos of objectivity and neutrality that did not naturally lead to political activity, described as a ‘traditional hesitation to speak out’ by a group that lobbied for scientists’ rights in the 1980s (Agar, 2019).[27]

Interviewees primarily saw themselves as professional scientists working in government, rather than public servants who did science, confirmed by these comments from David Dunford: ‘In your own mindset, you’re not a civil servant who turns up as an EO [executive officer] in a work and pensions office, you’re there as an engineer or a scientist, that’s your professional career and that’s what you do. We realised we were working for the national good, certainly when I started that was the case [yet] I didn’t really think of myself as a civil servant, in fact in the whole of my career I never thought of myself as a civil servant. I was employed by the civil service…but I was a scientist at the Royal Aircraft Establishment, DRA, DERA, QinetiQ.’[28]

A large part of this professional identity was derived from the relative autonomy that interviewees felt they enjoyed in addressing their work, reinforced by a managerial style remembered by Sarah Herbert and others as one of vague instructions and absence of close supervision, both internally and at a departmental level: ‘There was very little direction at that time at all. There’s no wonder that they altered how materials research worked because nobody really told me what to do, so I worked out a research programme of my own, not perhaps very inventive to start off with, but it taught me how to make the composites.’[29] David Dunford gave a similar description: ‘We were left to our own devices. People were committed, they wanted to understand…a lot of the individuals had been involved in the development of materials, the Comet accidents and understanding materials, there was a lot of experience there, a lot of practical knowledge that was focused on understanding and growing.’[30]

However, this approach had inconsistent outcomes, with the downside that people ‘reinvented the wheel’[31] or did nothing, as this extract from Mike Westby shows: ‘We lived in a bit of a closed community, our links with the outside world were not good. We probably could have got help but we didn’t. There was a very strong element of ‘not invented here’. It was interesting the atmosphere we worked in…for a research section, innovation was not terribly encouraged. We used to measure forces on things, we also used to measure how hot things got, which is a feature of things travelling at very high speed, but there were also things we were vaguely aware of where you could make [other] measurements. […] There are lots of things you can do to get quantitative data out of the airflow, we never did that because two of the elderly gentlemen tried to do that in about 1973 and the technology wasn’t up to it, they’d failed. […] It became received wisdom within the section that that could not be done. So, we never tried it again. […] Eventually we got a very bright Cambridge Physics graduate who just made a rig and made it work because he hadn’t been around long enough to learn that it couldn’t be done. […] We did a lot of stuff ourselves and probably held ourselves back quite badly by doing that.’[32]

Anthony Bravery’s perspective highlighted how this enabled scientists to fulfil their responsibilities as part of the civil service machine. ‘In a sense we were left to our own devices to do the right thing and to know what the right thing was. We knew that our principal objective was to provide robust technical and scientific advice to Ministers where there were going to be policy decisions, that drove what we did, we knew the science, we knew the technology and we knew where the gaps in the knowledge were.’[33]

For many scientific civil servants, part of the attraction of working in a GRE was the prospect of a ‘researchy-type’ job, as Anthony Bravery explained: ‘Whereas in university it was a blank sheet of paper type research, it would be whatever the department’s specialities were, and the members of research staff, or in industry it was very focused, and government was between the two.’[34]

Audio 5 : Mike Westby, scientific civil servant and aerospace engineer, reflects on the appeal of working at the Royal Aircraft Establishment (image credit: Bill Knight) © British Library https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/231903/022

Audio 6 : Paul Cannon, former scientific civil servant and space weather expert, reflects on the appeal of working in a government research establishment (image credit: Bill Knight) © British Library https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/231903/023

The development of individual technical knowledge was highly valued, demonstrated in the provision of further education opportunities at all levels. Shirley Jenkins was promoted to ASO provided she worked towards a diploma in technology.[35] The careers of exceptional researchers such as Chris Peel advanced via a separate ‘Individual Merit Promotion’ scheme which supported the development of deep expertise: ‘It stemmed from the old scientific research idea of having basically an administrative career progression or a science career progression, and everybody who came in as a scientist should have been able to get to their career grade which was PSO but thereafter there were two options open to you. Remain as an individual scientist or switch into administrative roles. […] I had to convince my then boss that I didn’t want to become an admin wallah because he’d earmarked me to run a division and I said, no, I don’t want to do that, I want to stay in the individual merit scientist role…from my point of view running the admin side was completely boring and a waste of space, but that’s a personal attitude, some people like it.’[36] A 1980 review shows that only one in five of the grades above PSO were filled by ‘special merit’ scientists such as Chris Peel, so the majority of staff were regarded as generalists, or ‘Jack of all trades’ as Phil Catling described himself (Civil Service Department, 1980).[37]

The civil service career frameworks also detached pay awards from individual scientific achievement, as Roger Courtney remembered:[38] ‘It was virtually unknown for somebody not to get their annual increment…it didn’t matter whether you had been judged totally outstanding or marginally competent, the way of rewarding someone who was outstanding was to put them on the promotion list, not to push them up their pay scale. That was the only tangible way that I knew I was doing alright when I appeared on promotion lists. […] One of the things perhaps I’ve appreciated much more in the last 15 to 20 years was the fact that you really didn’t have to worry about your income. You might complain that civil servants were not very well paid but on the other hand the money was always there in the account at the end of the month, and the pension was accumulating.’[39]

Anthony Bravery’s comment confirmed how advancement was marked by promotion rather than pay increases: ‘If you’re a junior scientist you came in as a SO you knew there was a SSO, PSO, SPSO, Deputy Chief SO and there was a structure. You would come in and have an idea, an aspiration of how far up that relatively short ladder you thought you might get, and that was a motivation, especially in science because in science you could climb that ladder not according to whether there was a vacancy but according to how good you were and how well regarded you were by your peers. So, there was a culture round the place, if somebody got promoted, your first question was “How old are they?”’[40] However, further remarks from Bravery showed how peer recognition from the wider scientific community remained an important aspect of their reward systems.

Audio 7 : Anthony Bravery, former scientific civil servant and fungi expert, reflects on the reward of having the results of his research published in a peer reviewed journal (image credit: Bill Knight) © British Library https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/231903/024

Funding for GREs was allocated on an annual basis from the parent department’s budget. While parent departments commissioned the research programmes, GRE scientists were involved in their design and in providing estimates that fed into the department’s overall budget which was then authorised by a vote in the House of Commons (Beard, 1982; HM Treasury, 2011; Ministry of Defence, 1979). This funding arrangement was commonly referred to as ‘the Vote’, allowing GREs ‘the luxury of a fixed income stream, with costs controlled by rigid adherence to staffing targets’ (Robinson, 1999).

Sarah Herbert commented on the rationale for the Vote system of funding for GREs: ‘[Government] don’t fund it in order to develop a product, it isn’t commercial, they fund it in order that MOD can develop a pool of knowledge so that when they come to buy equipment off defence firms, they actually have some knowledge of the technologies that are in the product they are trying to buy. So, they actually fund research to get what they call intelligent customer status. […] They have got the knowledge through the research establishment to be able to assess this purchase correctly.’[41] This tallies with Chandra Mukerji’s argument that government has an interest in ‘maintaining a labor force of skilled scientists available for consultation on policy issues’, observing that ‘funding makes the expertise of scientists (the skills and knowledge they embody) more consistently relevant to state interests and visible to government agencies’ (Mukerji, 1989).

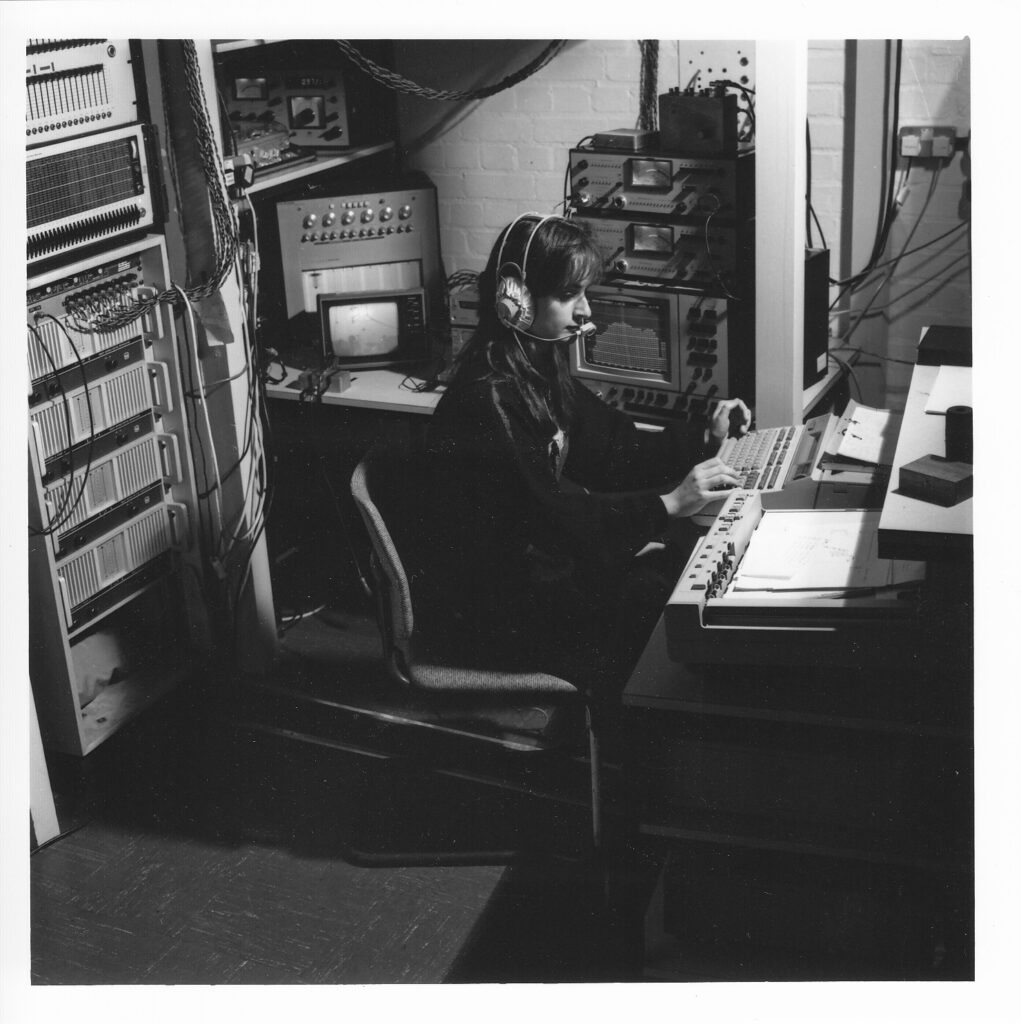

As Ian Linsdell’s quote explains, the annuality of the Vote system contributed to an investment in facilities and equipment that contrasted with the situation in universities when UGC equipment grants were being stretched by the mid-1980s (House of Commons Education, Science and Arts Committee, 1985, p 118). ‘The Vote system did not lend itself to a true appreciation of what it ought to have cost. Under the Vote system government allocates the amount of funds as per the long-term costings, which is what we were providing. If it so happened that throughout the year your spares usage or capital assets or requirement was less than it might have been, or your material spend wasn’t everything it might have been, it was not in your interest to underspend the budget. So under the Vote system every year inevitably you would have an end of year splurge where people would buy all sorts of things just to spend the budget and thus justify the allocation for next year.’[42] Susan James’s description of the equipment used in acoustics research bears out Mike Westby’s memory of ‘lots of kit, equipment, shiny things’.[43]

Audio 8 : Susan James, scientific civil servant and expert in acoustics, reflects on the range of equipment in the acoustics lab at the Royal Aircraft Establishment (image credit: Bill Knight) © British Library https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/231903/025

Anthony Bravery recounted how this funding system influenced the GREs’ reputation: ‘[FPRL] was a working world that was full of fascination and intrigue and people and facilities. We were quite well funded, I almost always had the latest microscope, and I would go to universities or into industry and our equipment was usually better, more up to date. […] So in those days government science was valued and funded accordingly and it was regarded as prestige business. People would come to us to find out what the latest developments were.’[44]

However, the 1970s heralded adjustments to the structures of state-funded science. The 1971 Rothschild report on government-funded research and development (R&D) focused on applied R&D primarily with reference to the operations of GREs, recommending that relationships between parent departments and their research establishments should become one of customer and contractor (Lord Rothschild, 1971). This statement from Vic Crisp confirms the impact of the Rothschild report: ‘To be honest in the early days there was not a huge pressure at all because the research establishments until that time pretty much ran themselves. They got chunks of money from their parent departments and to a large extent they decided what to do. But this was at the time of the Rothschild report…and things were beginning to change when I first went there, they were beginning to be talking about having to have proper customers and all this kind of thing.’[45] This report marks the onset of a period of commercialisation and organisational change that would disrupt the familiar ways of working in GREs.

The impact of organisational change on scientists’ values

While the Rothschild report dominated discussions about government science during the 1970s, the 1980s saw the emergence of international ‘megatrends’ in public administration that aimed to achieve savings in public expenditure, improve public services and make government more efficient (Hood, 1989; Pollitt and Bouckaert, 2000). Conservative enthusiasm for bureaucratic reform was underpinned by a New Right antipathy towards existing levels of state involvement in the economy and a commitment to managerialism (Clarke and Newman, 1997).[46] This era of ‘New Public Management’ (NPM) meant that GREs were subject to the same scrutiny exercises and efficiency measures that were introduced across the civil service, along with the creation of arm’s length bodies called executive agencies, the promotion of managerialism, and the expectation of increased commercial activity. Alongside these civil service reforms, Conservative governments in the 1980s developed new perspectives on state support for science, announcing in 1987 that ‘industry must take the initiative for its R&D programmes’ (Office of the Prime Minister, 1987, p 5; Agar, 2019). While a future study may investigate how the introduction of NPM was experienced across a range of public sector organisations, this article is focused on its impact on government scientists.

Interviewees remember how the application of NPM introduced competition and pressures that were not part of the existing culture, igniting a process of cultural change in the workplace (Lægreid, 2014). The overall process of organisational change was summarised by Phil Catling based on his experience as a middle manager after RAE had been transformed into an executive agency.

Audio 9 : Phil Catling, former scientific civil servant and business group manager, describes how organisational change affected the familiar structures and processes at Farnborough as the Royal Aircraft Establishment was transformed into the Defence Research Agency (DRA) and then the Defence Evaluation and Research Agency (DERA) (image credit: Bill Knight) © British Library https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/231903/027

For Sarah Herbert it was remembered as ‘all of a sudden management became the Holy Grail’, encapsulating the general trend in bureaucratic reform in the 1980s.[47] According to Mike Westby, the focus on management meant ‘it was almost like a new class emerged of the sort of management types’.[48] New project management roles emerged in which technical capability was an asset but not necessarily expected (Civil Service Department, 1980). Responsibility for running scientific research programmes moved away from scientists to managers that did not necessarily have technical knowledge, as Chris Peel explained: ‘The habit…that caused some difficulty was the imposition of managers from outside. There was an attitude that business knew how to manage things better than the establishment, so we had a whole raft of business development type characters coming in from all sorts of places and some were very good, but an awful lot were rubbish. […] The business was absolutely about local people who were really expert talking to government customers directly, not having a general industrial-type attitude towards it, and they wouldn’t know the technology that was held in house. […] Actually finding suitable business managers to run these small groups was quite a tricky issue.’[49]

Interviewees that took on managerial roles in the new executive agencies were empowered by increased authority in decision-making processes while highly stimulated by the goal of making commercialisation work. David Dunford remembered that the organisational changes ‘excited me as I thought it would give us the freedom to operate differently […] there was a real need to make decisions, to try things, and we were given that empowerment to do it.’[50] Paul Cannon described it as ‘an exciting time’ allowing him to operate in an entrepreneurial way when it came to cultivating new customers beyond government. Some enjoyed accelerated rates of promotion that were not feasible in the more pedestrian processes of advancement in the civil service. Ian Linsdell admitted that ‘most of us that stayed with QinetiQ saw it as opportunity and a chance to do a bit better than we would have done under civil service terms […] I was fortunate in achieving some promotions which I almost certainly wouldn’t have done under a civil service background.’[51] However, the excitement of aiming for new organisational objectives was accompanied by a need for managers to cope with new pressures, what Ian Linsdell referred to as ‘nerve-racking’ moments.[52]

While interviewees who held the new managerial positions acknowledged the increased independence of action resulting from organisational change, for the working scientists the common assessment was that organisational change had the opposite effect by reducing their control over their work. The introduction of goals and targets constrained their expectations for autonomy, while opportunities to develop their scientific credentials were reduced. Performance measurement and accountability brought huge, unwelcome change in their ways of working with the ascendancy of timesheets, just as scientists in another government funded laboratory ‘resented the requirement to account for the seamless web of their day in the segmented bureaucratic and financial manner’ (Law and Akrich, 1996).

Susan James spoke of how accounting for time affected whether senior staff felt valued: ‘In RAE days you were fully utilised, there was never any downtime. You weren’t constrained by working on a particular contract, there was always research under the Vote funded side of things to do or a very specific request from MOD to go and do a noise survey. […] At QinetiQ today we have to account for every six minutes…if you’ve got no research then that’s where you’re very visible, you’re not just sitting there as a resource and an expert, you’re actually just an overhead. […] Now it’s very different and very stressful on a Friday afternoon filling in your timesheet. […] That’s when it became very visible whether your research or area of expertise was of interest to MOD or not.’[53]

Shirley Jenkins felt that the new systems affected how researchers operated, even for those who, like her, remained within government after DERA was split in 2001: ‘It then became much more important to do things on time and on budget and whether you actually achieved anything became sort of less important. Prior to that it was a matter of achieving things. Time and budget were in there, but they weren’t the drivers at that stage. […] You were aware, even in Dstl, there was some sort of commercialisation aspects to the way things were being done. […] Forms, more accountability in sort of report writing, quarterly reports had to happen…sticking to budgets. It became much more important to write your reports and have a nice glossy report on time, whether you actually achieved anything in that quarterly period seemed to have less importance, the important thing was getting the report written.’[54]

For Paul Cannon, it meant devising different approaches to ensure he delivered the expected outputs: ‘You developed new strategies for doing things. […] You would have kind of thought about something for ages before you wrote. That doesn’t work when you’re doing things against a timesheet. What you do is you start writing on day one before you even know anything. So you lay out the report and put the title there and then you start writing things because then if you run out of time you have at least got something. It’s a different way of thinking but it’s much harder to manage staff in those circumstances. Maybe it’s hard to manage because you have to manage them. In the old days you didn’t have to manage them because it was all quite airy fairy.’[55]

He went on to describe his understanding of what changed with the managerialism: ‘One of the disadvantages that we saw as we became DRA and DERA was that with all the management processes that actually constrained the way we did things, we produced far less poor work – so that was really good – but I also felt that we lost those extraordinarily able people who didn’t have the freedom to do the things that they would have done in the past. […] The idiosyncratic people who…quite often manage to do something that’s rather special. That’s less and less acceptable I’m afraid in modern science, which is a shame. […] This applies to the universities as well…you’re being measured the whole time so you’re constrained in what you can risk doing at any time.’[56]

The stricter focus on accountability had a knock-on effect on the development of experts and range of specialist facilities for which the GREs were renowned, as Anthony Bravery explained: ‘The problem was we became so obsessed with costs and who was going to pay for it. Lots of activity ended up being called overheads, and overheads were not valued. Some of the basic processes of maintaining the facilities, for example, the products and processes that we worked with, fungal collections and insect collections, for example. These were very difficult to attach a value to, but very easy to put a cost to. These became unfashionable activities when there was a lot of pressure to reduce overheads. For the first time we had numbers going around how much a square metre our lab space cost for example, which put pressure on to reduce the number of rooms that you had and the size of those rooms. […] We had lots of specialist rooms, constant temperature rooms for growing culture and fungi, carrying out tests with fungi. Lots of rooms for breeding insects, including a termite breeding house, the pressure was on to reduce these, I had a bottom line to meet.’[57]

Susan James commented on how working on a contractual basis affected another aspect of doing research: ‘There’s never any thinking time. You could cost in a literature search at the beginning to understand what’s gone before but quite often that’s the bit that gets chopped off because you need to reduce the budget. So…perhaps it’s not as robust as it could be. Whereas before I always felt we did a really good robust scientific exploration, now it’s “right we’ve said we’d do this and OK, so we’re not quite sure what’s going on over here, but we’ll just have to park that”. […] It’s not as deep and robust as the kind of research we did in the past.’[58]

According to Sarah Herbert, the creativity that led to innovations and inventions was constrained by the increasing demands for scientists to account for their time and meet targets: ‘I think the thing that got lost in it all was, as they became more management orientated, accountable for the money they spent, tried to get industry to do some research etcetera, was the ability to just innovate. New bright ideas coming out of it started to disappear.’[59] David Dunford held a similar view: ‘As the structure of the funding changed and became more project-driven, more project-oriented with more cost control, more structured delivery in time, I think that changed the nature of what I would call innovative research. The customer changed, the customer was focused on an outcome that he wanted to pay for, and you had to try and deliver that outcome. You didn’t have the free rein to explore your ideas…as in the past.’[60] In these comments, the ability to innovate is clearly related to a sense of autonomy in the workplace.

David Dunford also used the word ‘buzz’ to describe what had disappeared from the workplace, making a direct connection between the increasing pressures of commercialisation and scientists’ ability to be innovative: ‘There was a buzz that disappeared from this, the informal banter and all the other things, it changed. […] When you’re continually up against it trying to deliver projects and generate revenue there’s a responsibility on individuals. […] I noticed there was probably a lot more stress…they won’t be so creative, they’ll tend to do the job. To have someone who’s creative you’ve got to give them free time or let them be a free thinker, if you’re forcing them to work on projects – deliver, deliver, deliver, deliver – you lose that creativity. You lose that “Why don’t we try it this way?”. You don’t get paid to try on a project.’[61]

Steve Rooks pointed out how organisational change made the job feel more ordinary: ‘It took a long time before you started recognising that things had changed. The biggest thing for us was that we were now being asked to stop being an academic organisation. […] You had a load of people from the DERA days that had previously been all excited about doing academic research and producing papers. […] When we went to Dstl that stopped overnight because we were effectively told that you are not here now to publish that, you are here to act as the intelligent customer to integrate knowledge that’s out there. That was quite a big shift. The organisation is very different now, the pace of change now is that while they enjoy what they’re doing, they don’t get the buzz they used to have, it’s more of a treadmill job, they come in and do their job and they don’t get a lot of time to interact and socialise in work as we used to […] we don’t have that same sense of fun about it.’[62]

A letter to the in-house newspaper at DERA gives another insight into the impact of reforms on the morale of individual researchers. A manager returning from a three-year secondment to MOD wrote about how attitudes had changed: ‘People were no longer constrained either by grades or by a rigid management structure. However, something was clearly not quite right. Individuals no longer “owned” a problem and were certainly not so prepared to put in extra effort to get a result. […] Our system of matrix management has effectively removed the feeling of being part of something permanent. I’ve seen a big change in morale in three years’ (DERA News, 1998).

Organisational change affected career prospects. Management became the clearer route for advancement as less emphasis was placed on the provision of clear technical paths. Interviewee reflections suggest that deep expertise came to be seen as less valuable and changing recruitment strategies brought in personnel with broader, interchangeable skills. This clip from Susan James voices her concern that one of the consequences of moving into a research environment funded through contracts rather than the Vote is the decline in opportunities for the tacit transfer of knowledge.

Audio 10 : Susan James, scientific civil servant and expert in acoustics, reflects on the importance of learning from her mentor Graham Rood at the Royal Aircraft Establishment (image credit: Bill Knight) © British Library https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/231903/029

New entrants themselves became less attracted to following a specialised career path, as Paul Cannon observed: ‘They know they do not want to be a specialist…partly they don’t see a career progression for specialism, they know it’s hugely risky, and it is. When you were in the civil service and building capability for the future, well there was some risk, but if you’re a commercial organisation, if the money goes away, the job goes away, you’re potentially redundant…you just don’t want to be in that position. So, it’s a very different philosophy.’[63] Mike Westby also commented on this trend: ‘There’s been a tension ever since the start of the agency shift…a continual perception, mainly by people who are deep experts, that deep expertise is not valued, and if you continue doing the same thing your career will stall at quite an early level and the people who get on move around a lot and become far more generalist and have a lot of contacts. […] It’s getting the balance between the two.’[64]

While Shapin showed that managers and scientists in industrial R&D laboratories accepted from the outset a working environment in which professional values were balanced against the demands of the corporate world, the changing expectations arising from privatisation required GRE scientists to adapt to an environment that they had deliberately avoided as a career choice (Shapin, 2008). Paul Cannon summed up this conundrum: ‘The problem for those of us that had been in the civil service was that we had to adapt to a new way of working. We’d been recruited to be civil servants…and we developed a civil service mentality of public service. We’d learnt to have those freedoms and we expected to have those freedoms, and when we moved into a more market driven approach then that wasn’t possible. We were conditioned to believe that it should be possible. If we’d all worked in industry in the first place, we wouldn’t have had the same stresses and strains. It was hugely, hugely stressful for most people. I’m not saying the management was bad at all, I’m not saying from the top down people were being uncaring, it was simply that the demands of the new role were not ones that people adjusted to.’[65]

For some, the change of ethos and outlook proved too stressful, as Anthony Bravery observed: ‘I had research managers, very good people, internationally respected for what they knew, they found this very difficult and more than one literally crumbled under it. People who were reduced to such a level of anxiety that it was classified as nervous breakdown, they went off sometimes for long periods of time and had to be covered because the contract still had to be delivered. So, a lot of pressure brought on. […] In the monthly management meeting we looked at progress on current contracts and looked at business development…it was a question of looking them in the eye and saying, ‘What have you got going, who are you going to see, what are your ideas, what are you trying to do?’ […] For a long time, we were sustained by ongoing projects, contracts from government.’[66] This clip from Paul Cannon reveals how traumatic the process could be.

Audio 11 : Paul Cannon, former scientific civil servant and space weather expert, reflects on the impact that organisational change in the Defence Research Agency had on the mental health of a colleague (image credit: Bill Knight) © British Library https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/231903/030

Changes in management and career structures, the rationalisations and signs of impending privatisation prompted some interviewees such as Phil Catling to join the union for the first time. ‘I’ve never been a trade unionist or felt much for it or needed trade union representation. […] With the redundancies looming then I was keen to hear what the unions were doing so I did join towards the end. Their involvement was…not militant at all.’[67] Catling’s description is borne out by the absence of references in the interviews to organised activity in protest at privatisation. Written records held in the BRE archive suggest that the negotiations that accompanied ownership transfer were cordial, despite the discontent expressed by staff in meetings that covered their changing employment conditions, redundancy agreements, transfer of pensions and union status (BRE Archive, 1996). One reason for this may be that by the late 1990s unions had come to accept the roll-out of the government’s privatisation programme, as suggested in Ian Linsdell’s description of negotiations over redundancies: ‘If we needed to change practices or any aspect of the business we would consult with the unions, explain what needed to change, and get the unions to buy in on behalf of the members to that process. […] In large measure the people we negotiated with were aware of our objectives…and were looking to help us achieve it in the most pragmatic manner.’[68]

When organisational change unfolded, many experts either took early retirement or were made redundant. Mike Westby, who still works for Dstl, is aware of the consequences of these processes on the organisation: ‘I think there’s less deep expertise than there was. It’s got a bit better in fairly recent times but certainly what you might call the grey beard generation, the real deep experts who’d stay in the same area for perhaps 20, 30, 40 years, they all disappeared, and nobody really followed them on. So we lost a lot of deep expertise which was not replaced. It’s something we struggle with still where we did lose a generation of experts and we’re trying to recreate it again.’[69]

Observations such as these indicate how organisational change had long-term consequences not just on individual scientists but also at a national level. Privatisation of many GREs meant that the scientific civil servants who had previously circulated through Whitehall on their ‘tour’ in London were no longer represented in central government. Further historical study might consider central government departments’ ability to act as intelligent customers in an increasingly commercial environment at the time the internal cohort of technical experts was dramatically reduced.

Conclusion

During the twentieth century research establishments attached to government departments made an extensive and visible contribution to national and international research systems. In the conduct of government-funded scientific research GRE scientists were not operating solely within the framework of the civil service but were actively engaged with the broader community of professional scientists (Rothblatt, 1985). They interacted with colleagues within the civil service but also liaised and collaborated with peers in academia and industry in carrying out the research commissioned by their parent departments, combining theoretical knowledge with practical skills to carry out their work in a variety of settings. Perceptions of working in the scientific civil service encompassed public service and job security along with bureaucratic constraints, participation in exciting and stimulating programmes of research, camaraderie with an extensive network of peers and a culture where using one’s own initiative was central to the development of individual and institutional knowledge.

These new oral history interviews show that understandings of working life as a scientific civil servant were profoundly affected by the complexities of organisational change and commercialisation which altered the operating frameworks of GREs from the 1970s, introducing an alien set of expectations and pressures into the workplace. Scientists’ notions of autonomy in the management of the research diminished as responsibility for the timely delivery of customer contracts passed to the project managers. Project management rather than a technical path became a clearer route for career advancement. The constraints of accounting for time replaced the sense of freedom they had enjoyed in their daily work so that professional value to the organisation became linked to hours booked to projects rather than for individual skills. Transfer into the private sector, with the need to chase business opportunities, meant that scientists found themselves competing against former partners, upsetting the established web of connections that were understood to facilitate the transfer of knowledge. Interviewees felt this had a negative effect on their ability to be creative and innovative.

The oral history interviews also reveal the contradictions between individual experiences. Mike Westby referred to operating in a closed world, while others remembered the job being defined by ‘a big raft of interactions’.[70] Westby also refers to a lack of imagination among his colleagues, while others speak of the ability to be creative that came with relative autonomy in the workplace. There are stories of the challenges and opportunities for managers, yet one of the more consistent themes to emerge from the interviews is that of loss on the part of the working scientists. The loss of freedom in how they could carry out research, the loss of a sense of fun and camaraderie as they went about their work, the loss of treasured scientific facilities that underpinned their specialist work, the loss of prestige associated with the GRE institutional heritage, and ultimately the loss of deep expertise and institutional memory. These combine to suggest that through commercialisation, GRE scientists lost a central aspect of their scientific and personal identities, the feeling of being recognised as part of something special. As Paul Cannon commented, ‘We lost a type of job for a type of person in this country’.[71]

Acknowledgments

Thank you to all the interviewees who generously shared with me their experiences of organisational change in government research establishments. In writing this article I have appreciated the feedback provided by the reviewers and journal editor, and throughout my PhD I benefitted from insights offered by many members of the academic community, in particular my supervisors Dr Sally Horrocks and Dr Rob Perks. Using oral history in this way would not have been possible without the support and expertise of the National Life Stories team at the British Library, and special thanks to archivist Charlie Morgan for his help in making accessible the sound clips included here.

Appendix A

British Library (BL) C1802: Privatisation of UK Government Science: Life Story Interviews.

Roger Courtney, interviewed by Emmeline Ledgerwood, Watford, 2018, BL C1802/01. http://explore.bl.uk/BLVU1:LSCOP-ALL:BLLSA8071349

David Dunford, interviewed by Emmeline Ledgerwood, Farnborough, 2018, BL C1802/02. http://explore.bl.uk/BLVU1:LSCOP-ALL:BLLSA8108329

Vic Crisp, interviewed by Emmeline Ledgerwood, London, 2018, BL C1802/03. http://explore.bl.uk/BLVU1:LSCOP-ALL:BLLSA8108331

Martin Wyatt, interviewed by Emmeline Ledgerwood, Watford, 2018, BL C1802/04. http://explore.bl.uk/BLVU1:LSCOP-ALL:BLLSA8136153

Pam Turner, interviewed by Emmeline Ledgerwood, Fleet, 2018, BL C1802/05. http://explore.bl.uk/BLVU1:LSCOP-ALL:BLLSA8161031

Carol Atkinson, interviewed by Emmeline Ledgerwood, Hemel Hempstead, 2018, BL C1802/06. http://explore.bl.uk/BLVU1:LSCOP-ALL:BLLSA8161032

Chris Peel, interviewed by Emmeline Ledgerwood, Fleet, 2018, BL C1802/07. http://explore.bl.uk/BLVU1:LSCOP-ALL:BLLSA8168103

Susan James, interviewed by Emmeline Ledgerwood, Church Crookham, 2018, BL C1802/08. http://explore.bl.uk/BLVU1:LSCOP-ALL:BLLSA8186305

Phil Catling, interviewed by Emmeline Ledgerwood, Farnborough, 2018, BL C1802/09. http://explore.bl.uk/BLVU1:LSCOP-ALL:BLLSA8207821

Chris Scivyer, interviewed by Emmeline Ledgerwood, Frogmore, 2018, BL C1802/10. http://explore.bl.uk/BLVU1:LSCOP-ALL:BLLSA8216908

Steve Rooks, interviewed by Emmeline Ledgerwood, Meonstoke, 2018‒19, BL C1802/11. http://explore.bl.uk/BLVU1:LSCOP-ALL:BLLSA8221835

Alan Gray, interviewed by Emmeline Ledgerwood, Malvern, 2019, BL C1802/12. http://explore.bl.uk/BLVU1:LSCOP-ALL:BLLSA8257397

Sarah Herbert, interviewed by Emmeline Ledgerwood, St. Mary’s Bay, 2019, BL C1802/13. http://explore.bl.uk/BLVU1:LSCOP-ALL:BLLSA8257412

Andrew Cahn, interviewed by Emmeline Ledgerwood, London, 2019, BL C1802/14. http://explore.bl.uk/BLVU1:LSCOP-ALL:BLLSA8257418

Mike Westby, interviewed by Emmeline Ledgerwood, Hedge End, 2019, BL C1802/15. http://explore.bl.uk/BLVU1:LSCOP-ALL:BLLSA8257422

Anonymous, interviewed by Emmeline Ledgerwood, Hedge End, 2019, BL C1802/16. http://explore.bl.uk/BLVU1:LSCOP-ALL:BLLSA8301826

Shirley Jenkins, interviewed by Emmeline Ledgerwood, Farnham, 2019, BL C1802/17. http://explore.bl.uk/BLVU1:LSCOP-ALL:BLLSA8301828

Anthony Bravery, interviewed by Emmeline Ledgerwood, Longwick, 2019, BL C1802/18. http://explore.bl.uk/BLVU1:LSCOP-ALL:BLLSA8316597

Paul Cannon, interviewed by Emmeline Ledgerwood, Colwall, 2019, BL C1802/19. http://explore.bl.uk/BLVU1:LSCOP-ALL:BLLSA8342561

Ian Linsdell, interviewed by Emmeline Ledgerwood, Titchfield, 2019, BL C1802/20. http://explore.bl.uk/BLVU1:LSCOP-ALL:BLLSA8342609

Robyn Thorogood, interviewed by Emmeline Ledgerwood, Haddenham, 2019, BL C1802/21. http://explore.bl.uk/BLVU1:LSCOP-ALL:BLLSA8342611

Peter Levene, interviewed by Emmeline Ledgerwood, London, 2019, BL C1802/22. http://explore.bl.uk/BLVU1:LSCOP-ALL:BLLSA8374054

John Chisholm, interviewed by Emmeline Ledgerwood, Rickmansworth, 2019, BL C1802/23. http://explore.bl.uk/BLVU1:LSCOP-ALL:BLLSA8385302

Appendix B: transcripts

Audio 1