Book review: Curious Devices and Mighty Machines: Exploring Science Museums by Samuel J M M Alberti (Reaktion Books, 2022)

Keywords

collections research, exhibitions, Museum collections, museum history, science museums

‘What is a science museum?’ is the first question the reader encounters on this journey into the heart of science and technology collections. Science museums are special, representing a range of often contradictory qualities. They tell complex stories but make them fun and engaging. They are contemporary and relevant, while still acting as custodians of history and material heritage. Science museums are among the most popular tourist attractions in the UK, yet so many of their collections and processes exist away from the public eye. With the benefit of an ‘insider’s eye’ it is these paradoxes that Samuel Alberti’s Curious Devices and Mighty Machines: Exploring Science Museums delves into. Alberti is currently Director of Collections at National Museums Scotland and previously worked at the Manchester Museum and the Royal College of Surgeons (which includes the Hunterian Museum). His insider’s perspective lends this volume a warmth and enthusiasm that can only come from years spent in the study, care and interpretation of science and technology collections. Anecdotes (such as that of the museum colleague whose daughter demanded a new phone when she saw her current model in a National Museums Scotland exhibition, assuming hers was now considered old) and insightful interviews with museum staff, only add to the sense that the reader is being given exclusive access to the ‘idiosyncratic past and intriguing current practices of these institutions’.

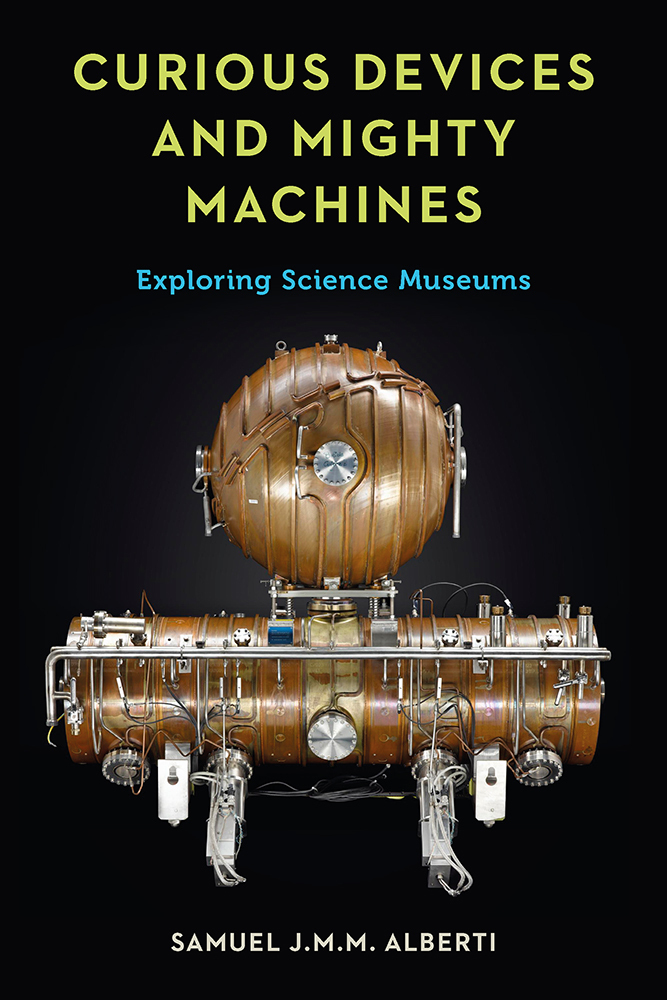

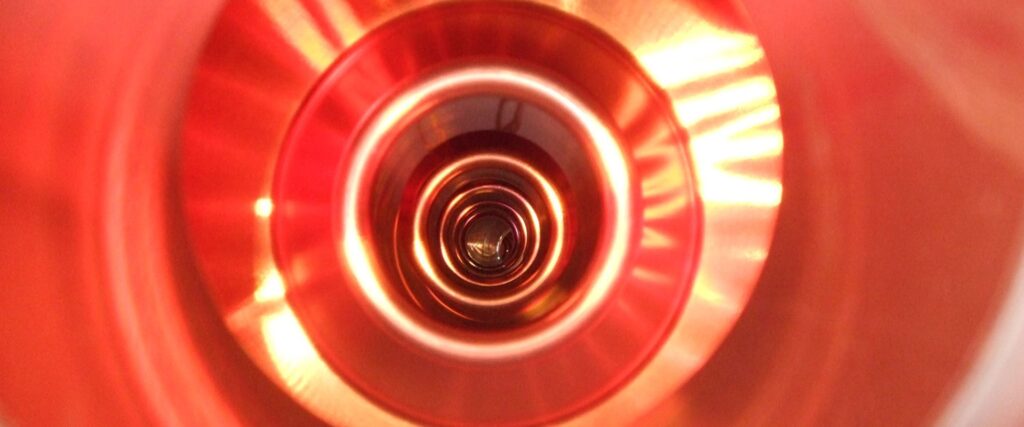

Across six chapters, Alberti considers the significance of the ‘collections of scientific material culture’ cared for by science museums. Collections are at the heart of this book as illustrated by the beautifully photographed objects interwoven with the text, opening, for example, with one of the ‘128 accelerating cavities that were once positioned around the vast loop of the Large Electron-Positron Collider’ from CERN in Geneva, which is currently in the National Museums Scotland Collection. Alberti asks why objects such as this, and thousands of other science and technology objects, belong in museums and explores how they are collected and used. While delving into a dizzyingly diverse range of collections (‘science, technology, transport, sometimes agriculture, a bit of medicine’) Alberti is also asking us to consider the broader question of what museums are for.

This is an analysis that does not stray from the traditional and western-centric idea of a museum, as Alberti acknowledges in his decision to focus on the ‘main players’ in Western Europe and North America. Given current trends within museums and academia that push beyond this paradigm, this could feel like a missed opportunity, particularly given the cross-institutional connections and relationships that existed when ‘museums of all kinds were tools of empire’ (as Alberti identifies in chapter 1). Current debates around representation, diversity and colonial legacies in museums are picked up in a later chapter on ‘Campaigning with Collections’ where the overrepresentation of certain classes and ethnicities within the museum sector is commented on. However, this is not the focus of this book, and Alberti is intentionally giving us a connoisseur’s tour of significant or intriguing objects and collections within institutions that speak to a very particular lineage of museums. This is not a light read, nor is it overly autobiographical. Rather this book presents a professional view on significant questions and the theoretical challenges faced by anyone who works with historically significant collections. Well-researched and with an invaluable bibliography, there is plenty that could be brought into dialogue with current scholarly debates around access to, and uses of, material culture.

The first chapter of Curious Devices and Mighty Machines gives the reader a brief survey of the origins of science museums and the influence this history has had on their institutional identities. Focusing on the nineteenth and twentieth century, Alberti draws out the discussions around collections and interactivity, power and politics, and the influence of the passionate and dynamic individuals that appeared within these institutions. From the performative power of exhibitions to the political discourse around the Public Understanding of Science (PUS) movement, Alberti reveals the idiosyncrasy and hybridity of science museums. The four chapters that follow mirror the core responsibilities of curators: considering how science and technology is collected; how these collections are stored and managed; and how their stories are used to engage audiences. Using a range of examples, Alberti brings the practical questions curators pose of museum objects into dialogue with the more cerebral concerns about what and why institutions collect, and how storytelling can be used to enliven sometimes dull, sometimes intimidatingly technical subjects.

It is once we get into the real substance of the book that the benefits of being guided by a museum professional become apparent. It takes real curatorial enthusiasm to dedicate 42 pages to the often-overlooked theme of museum storage, in a chapter called ‘Treasures of the Storeroom’. Alongside more evocative photographs of objects and shelving that appears to vanish into the distance, Alberti includes rich descriptions of these hidden spaces. In revealing and recognising the constant work that goes into conserving, moving, studying and handling these ‘fragments of eternity’, Alberti renders stores into lively, multi-sensory environments, utterly distinct from the dusty, neglected spaces of popular imagination.

This is also not just a book concerned with the past or entirely with looking inwards. The chapter on ‘Engaging Objects’ opens with an image of ferrofluid and leads the reader into a discussion about present-day ‘science engagement’ and the exhibition development process that supports this aim. New tools for science engagement are considered, including Twitter and digitally accessible online collections. The chapter on ‘Campaigning with Collections’ shows the active role that science museums continue to play in the public discourse around a host of contemporary issues. Ranging from climate change to misinformation to human rights, Alberti treads sensitively through the ethical quandaries science museums often encounter when communicating with their audiences. From these more serious issues we are brought back to a final chapter that asks the reader once again to reflect on the human stories, past and present, that bring science collections to life. Alberti reminds us that while science museums keep science collections for lots of different reasons the most important is for ‘their visitors, audiences and users’ whose curiosity and joy in these encounters serve to enliven these objects.

Books that emerge out of practice are sometimes difficult to locate within rigid disciplinary categories, asking questions or addressing problems that cut across academic trends. However, despite Alberti’s claim that this is ‘more personal polemic than academic analysis’ I suggest that its interdisciplinarity is one the strengths of Curious Devices and Mighty Machines. Historians, and particularly Historians of Science or Science and Technology Studies will benefit from learning from someone with a keen eye for material culture. Museum professionals will recognise and respond to those practical challenges of storage, storytelling and audiences which Alberti is able to share with such authority. Museum Studies scholars and students who study the history and social impact of museums as institutions, as collecting organisations, and as memory sites, will appreciate a focus on an occasionally neglected category of museum: the science museum.

For the general reader, this ‘curatorial confessional’ props open the door into the behind-the-scenes world of museum practice and the joy that comes from working with material things. What shines through this volume is a love for collections and the institutions that acquire, house, and tell stories with them. As Alberti says, ‘[t]he door to the science museum is unlocked’; welcome to the quirky, contradictory, curious world of science collections.