Flying Scotsman: modernity, nostalgia and Britain’s ‘cult of the past’

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/160507

Abstract

Flying Scotsman is arguably the world’s most famous steam locomotive. The engine, a standard bearer of British engineering excellence and modernity in the 1920s, became, in the 1960s, a symbol of the dying age of steam. As Britain’s post war austerity and increasingly lesser role in the world gave way to Harold Wilson’s modernising ‘white heat of technology’ Britain’s ‘cult of the past’ took greater hold. Wistful nostalgia for the past can be seen across the cultural landscape of the 1960s in books, poetry, music, television and film. With a marked increase in the rise and popularity of preservation groups across the country this was a decade when interest in Britain’s ‘national heritage’ enjoyed enormous growth. Viewed within this context the remarkable saving of a steam locomotive from the scrapyard as Britain’s railway abandoned nineteenth century technology illustrates how the past has increasingly shaped Britain’s cultural landscape. This raises wider questions about what it means to preserve cultural objects and how, if at all, their authenticity can be preserved.

Keywords

Alan Pegler, British Railways, Flying Scotsman, London & North Eastern Railway, National Railway Museum, Sir Nigel Gresley

Introduction

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/Gordon backed down onto his train, hissing mournfully.

‘Cheer up Gordon!’ said the Fat Controller.

‘I can’t, Sir. The others say I have boiler-ache, but I haven’t, Sir. I keep thinking about the Dreadful State of the World, Sir. Is it true, Sir, what the diesels say?’

‘What do they say?’

‘They boast that they’ve abolished Steam, Sir.’

‘Yes, Gordon. It is true.’

‘What, Sir! All my Doncaster brothers, drawn at the same time as me?’

‘All gone, except one.’

The Guard’s whistle blew, and Gordon puffed sadly away.

It was indeed true. British Rail’s last main line steam hauled passenger train ran on 11 August 1968. That evening the BBC broadcast a documentary commemorating the end of what had been an integral feature of British life for over a hundred and forty years. The programme ends with the camera silently sweeping through a scrapyard past hundreds of redundant steam locomotives. But the film’s main focus was to celebrate the one that got away, a locomotive that had become symbolic of a passing age – its name and historic number gave the documentary its title: 4472 – Flying Scotsman (BBC documentary, 1968). This was the ‘one’ to which the Fat Controller had referred, the locomotive which gave the watching BBC viewers the last hurrah of steam as Flying Scotsman recreated, in May 1968, its May 1928 feat of hauling a train non-stop from London to Edinburgh. Amongst the passengers interviewed on that train was the Reverend W Awdry. Celebrated as the author of the Railway Series, the stories of the adventures of a group of locomotives on the Island of Sodor first published in 1946, Awdry would transplant the Flying Scotsman into his next book Enterprising Engines as the Fat Controller borrowed the famous locomotive to cheer up his depressed express engine Gordon. It proved to be an inspired move, as Flying Scotsman would tell his ‘brother’: ‘You are lucky, Gordon, to have a Controller who knows how to run railways’ (Awdry, 1968).

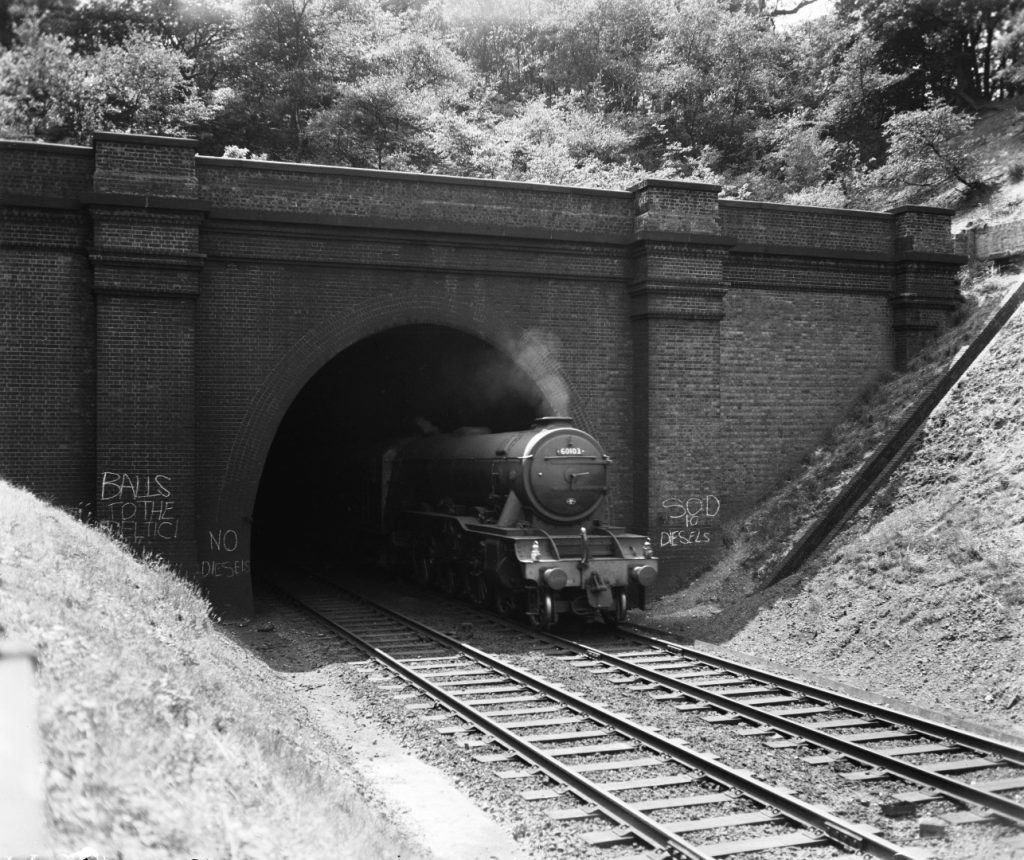

It is easy to see the inference Awdry was making in comparing the Fat Controller (who knew how to run a railway) with successive British Railways Board chairmen, notably Dr Richard Beeching who was popularly presented as destroying the railway. BR’s modernising programme and introduction of diesels in place of steam locomotion was a frequent target in Awdry’s books, where the diesels are largely presented as devious and deceitful characters.[1] This dislike was seen in the real world too: there is an illuminating photograph in the archives of the National Railway Museum showing Flying Scotsman leaving Welwyn North Tunnel in 1959. This was a time when the days of steam on the east coast main line were numbered as the introduction of diesel locomotives – notably the soon to be introduced Deltic – gathered pace. On the tunnel mouth someone has scrawled in graffiti, ‘Sod Diesels’ and ‘Balls to the Deltic’.

The end of steam had a profound effect on many. Commenting on the BBC documentary the television critic Henry Raynor remarked on ‘the amiable dottiness about our passion for steam engines and our nostalgia for the days when they roared across the country discharging a lot of steam and soot. But nothing man has ever made and forced into his service has so unmistakably declared its power as did a big railway engine’(Raynor, 1968). To understand why Flying Scotsman became the nostalgic symbol of this passing age we need to understand its importance as both a technological and cultural object.

The fame of Flying Scotsman

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/160507/002Few products of the industrial age have captured the imagination quite like Flying Scotsman. Completed in 1923 as the first locomotive of the newly formed London & North Eastern Railway (LNER), Flying Scotsman has, since 2004, been part of the National Railway Museum’s collection. An initial analysis would lead one to question why this particular locomotive enjoys a profile unlike any other. Flying Scotsman is not revolutionary in the way that George and Robert Stephenson’s Rocket was, nor is it the largest, most powerful or fastest steam locomotive – all features that could be assumed to provide a unique significance. Indeed, Flying Scotsman itself was not even unique as an example of engineering excellence, being one of a class of some 79 such locomotives (Flying Scotsman was built to Sir Nigel Gresley’s A1 design but was rebuilt to his improved A3 design in 1947). Nor was Flying Scotsman the first of its class (it was the third to be constructed), and while it held for a short time the world steam speed record (set in November 1934) this was soon beaten (in March 1935) by a sister locomotive Papyrus. Yet Papyrus was scrapped without protest while Flying Scotsman has a well-founded claim today to be the most famous steam locomotive in the world.[2] The reasons for this are varied and complex – there was no certainty that Flying Scotsman would survive to become the cultural icon it is today. Passed over for preservation in the early 1960s, the locomotive was earmarked to be scrapped. That it wasn’t and instead has gone on to become arguably the most recognised railway locomotive ever raises questions as to how we view our past and what it is that makes objects – large or small – significant to museum curators, enthusiasts, and the wider public.

The rescue and restoration of Flying Scotsman in 1963 and its subsequent operation unquestionably increased its fame. In 1966 the locomotive was hailed by John Noakes as ‘the most famous steam locomotive in the World!’ on the BBC’s flagship children’s television programme Blue Peter.[3] Noakes’s feature was in response to the programme receiving ‘lots of letters’ from children distraught at the withdrawal and scrapping of steam locomotives. This was an era when Britain was emerging from post-war austerity into a world without Empire and a time where it has been argued that a wistful nostalgia for the past took root, enhancing, in turn, the power of symbols of past ages (Cannadine, 2002). On Blue Peter – then watched by an astonishing seven million viewers – Flying Scotsman became a symbol for a vanishing way of life.[4]

Prior to preservation Flying Scotsman had enjoyed periods of great fame so its profile was not solely a product of the 1960s. The foundations of the locomotive’s celebrity in the 1920s and 1930s owes itself to a number of factors, some deliberate, others accidental. The key first point stems from the misunderstanding surrounding the ‘Flying Scotsman’ name and popular confusion about the differences between a locomotive and a train. This confusion played into the hands of Flying Scotsman, which was deliberately named by the LNER after a long established train of the same name. The ‘Flying Scotsman’ had for long been the unofficial name of the flagship service on the east coast main line connecting London to Edinburgh. In fact, it was not one train but two with simultaneous departures traditionally leaving the respective capitals at 10am each weekday. The train quickly established a reputation for speed and was known from at least 1864 as the ‘Flying Scotchman’ due, as the Oxford Times explained, to ‘the rate at which it travels’ (The Oxford Times, 1864). Such popularity manifested itself in other ways too: as early as the 1880s the service gave its name to the popular ‘Flying Scotchman’ pen which, its makers boasted, ‘glides like an Express Train’.[5]

The ‘Flying Scotchman’ became popular with businessmen, soldiers, politicians and diplomats. There are, for example, two known instances of the celebrated novelist Charles Dickens travelling on it (Dolby, 1912).[6] In 1897 it even became the subject of an article sitting alongside the latest Sherlock Holmes instalment, ‘The Adventure of the Speckled Band’, in The Strand Magazine (then enjoying a circulation of around 500,000) (Kitton, 1892). The train’s fame was justified as the southbound service opened up the London markets and helped cement Edinburgh’s role as a major financial centre; the northbound service gave access to Scotland as a tourism destination, a land recently popularised by Queen Victoria and the novels of Sir Walter Scott (it was no co-incidence that the ‘Flying Scotsman’ arrived into Edinburgh’s Waverley Station, which took its name from Scott’s most successful novel). Scotland’s increasing popularity as a leisure and tourism destination owed much to the popularity of this train.

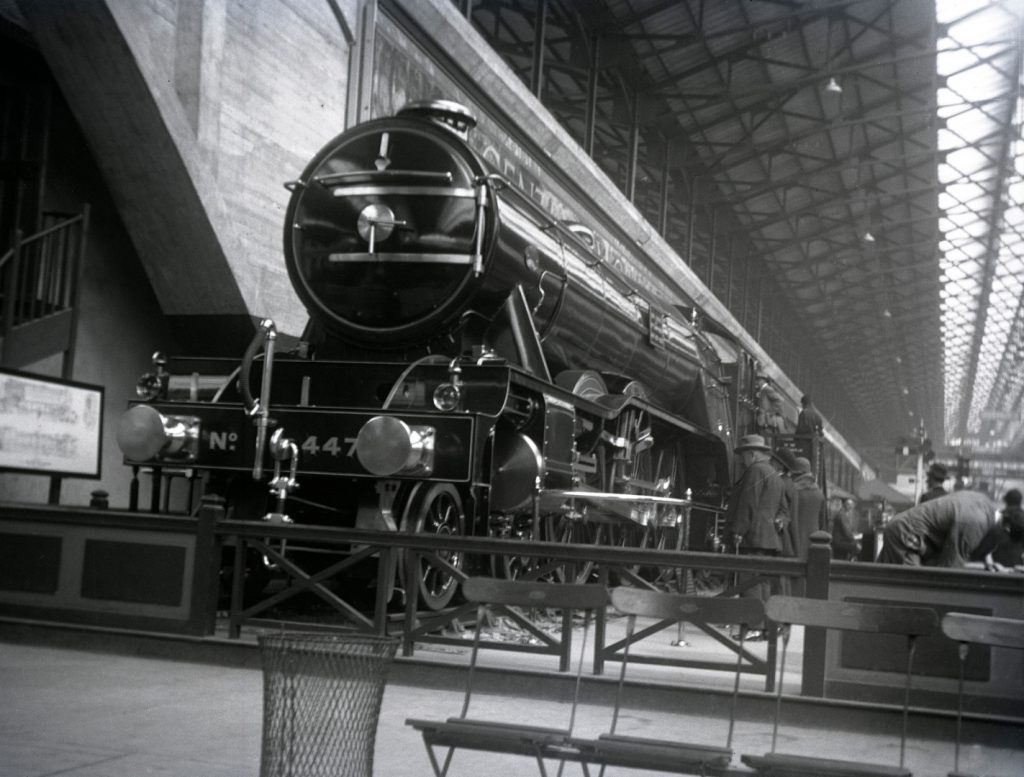

Therefore, when the LNER named Flying Scotsman in time for her appearance at the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley in 1924, the name was already well known.

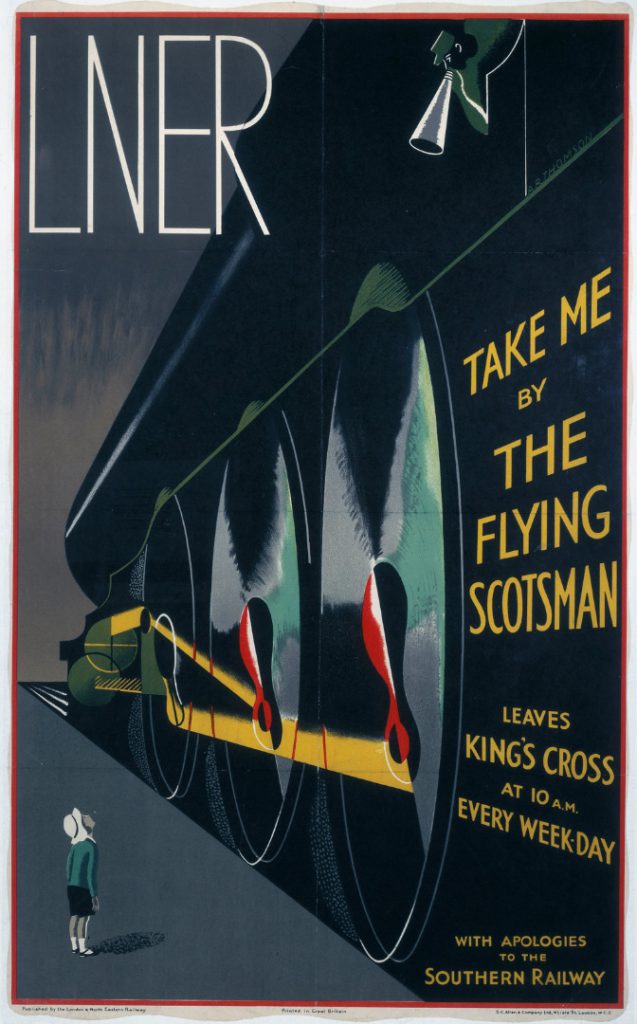

This was an inspired act of marketing by the still fledgling LNER – it could both showcase its latest and most powerful locomotive type whilst simultaneously advertising the company’s flagship service. The exhibition attracted a huge audience and enjoyed worldwide press coverage with Flying Scotsman a star exhibit. By 1928 the ‘Flying Scotsman’ service was being advertised as ‘The Most Famous Train in the World’ and the eponymous locomotive was being used to publicise the company and its service.[7] In May 1928 the locomotive hauled the first non-stop run of the northbound ‘Flying Scotsman’ amid much media fanfare; the following year saw the locomotive and train star in one of the earliest British talkie movies (appropriately named The Flying Scotsman) (McLean, 2016). Later publicity photographs would be taken of the locomotive and its regular crew of driver William Sparshatt and Fireman Webster shaking hands variously with Sir Malcolm Campbell and Geoffrey de Havilland, respectively the fastest men on land and in the air. On 30 November 1934, Sparshatt and Webster took Flying Scotsman on the world’s first authenticated 100mph run by a steam locomotive, thus becoming the fastest men on rails (McLean, 2016).

Speed, for long associated with the ‘Flying Scotsman’ train, was also used to publicise the service in ever more ingenious ways: stunts were organised with the train racing pigeons, speedboats and aeroplanes. The media were always on hand to record the moment. Many of Flying Scotsman’s sister engines were named after celebrated racehorses and the travelling experience positioned the train in the world of glamour, speed and innovation. Cinema, television and radio were trialled on board. There were other innovations too – hairdressing salons, ladies retiring rooms, air conditioning, ‘health giving’ windows, all electric kitchens, a Louis XV-style restaurant and even a cocktail bar – all designed as one contemporary commentator noted to ‘beguile in various ways, the hours of this lengthy journey’ (Allen, 1946). This was all cemented by expert advertising and consistent branding including a headboard designed by Eric Gill (one of the earliest uses of his Gill Sans font).[8] The ‘Flying Scotsman’ locomotive and train were positioned as modernist icons famed for speed, style and service.

The fame spread beyond the UK: the LNER advertised the service in North America through an agent based in New York, whilst it built on its already established movie fame through a significant role in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1935 film The 39 Steps (McLean, 2016).

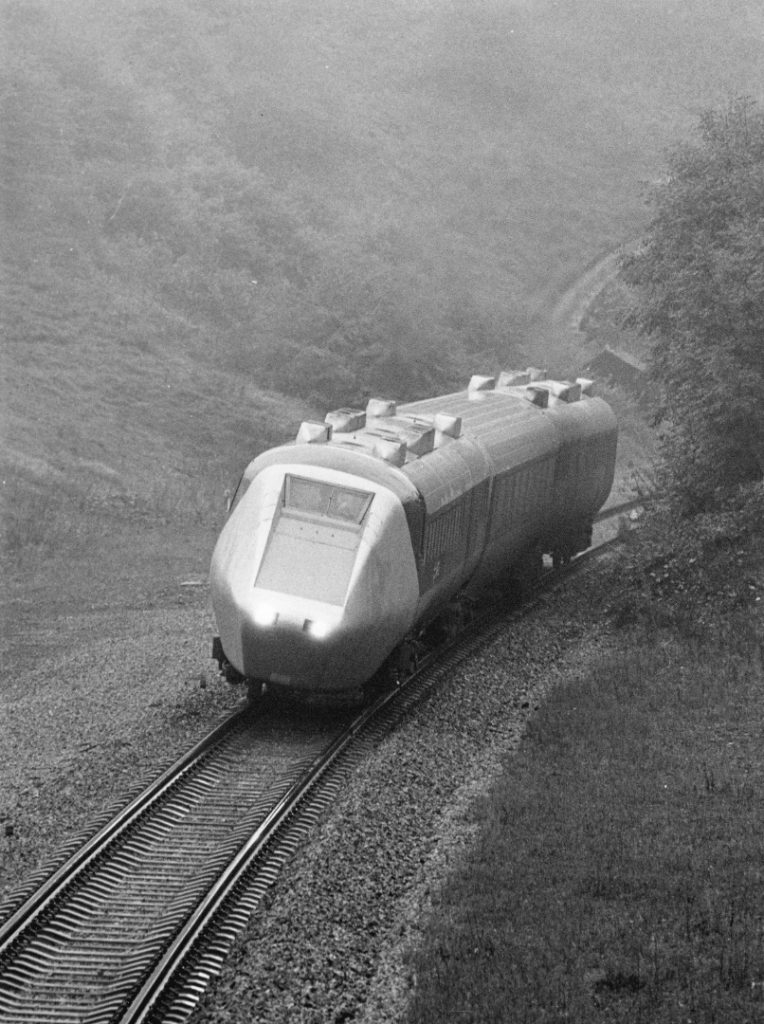

Throughout the first half of the twentieth century the ‘Flying Scotsman’ had been regularly refreshed with new rolling stock, the latest locomotives and the most up-to-date on-board features, thus ensuring that the service remained at the forefront of the modern British railway system. This tradition continued in 1962 – the centenary of the service – when the ‘Flying Scotsman’ was reinvented once more as symbolic of a new and modern era.[9] The latest rolling stock was provided for the train, which was to be hauled by the new Deltic diesel, a truly transformative development being not only fast and powerful but futuristic in its styling.

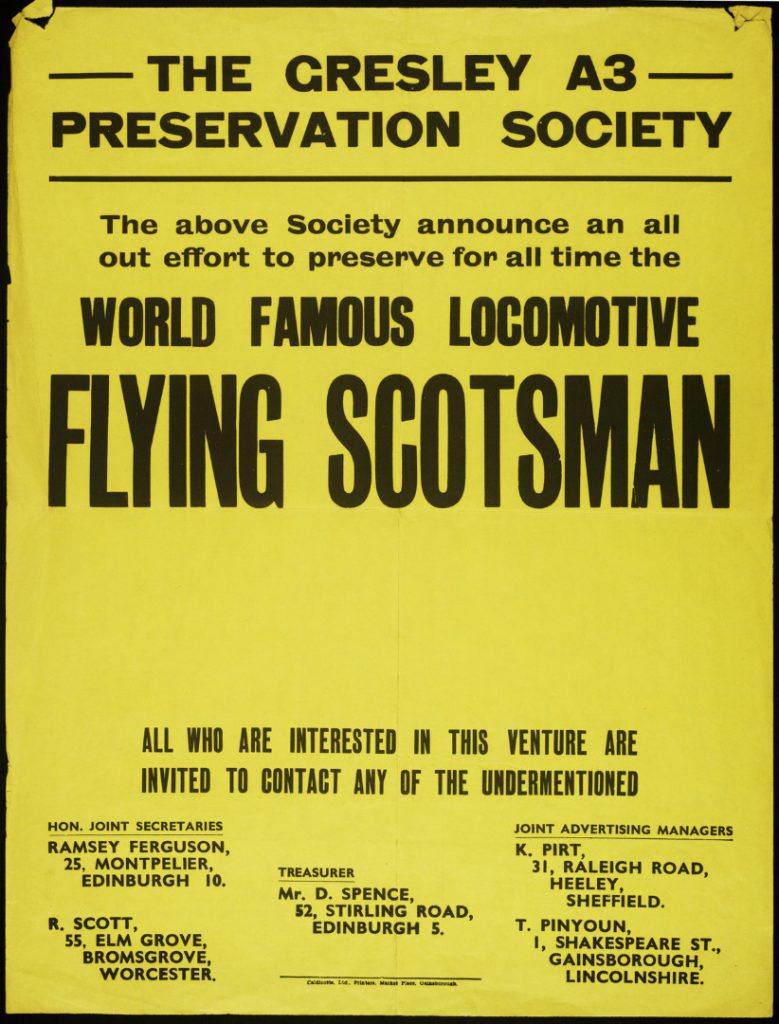

But in 1962 the future of the locomotive of the same name was less assured. The British Railways (BR) modernisation programme launched in 1955 marked the beginning of the end for steam. When it was revealed that steam would continue into the 1970s, BR accelerated the programme of scrapping locomotives (Gourvish, 1986). The statistics are revealing: in 1953 there were still 18,600 steam locomotives operating on the British railway system; but by 1962, Flying Scotsman’s last full year in service, the number had more than halved to 8,800 and within six years that had dropped to zero (Gourvish, 1986 p 275). To ensure historic locomotives or relics survived a number of locomotives were identified for preservation. However, amongst the omissions was Flying Scotsman, which was earmarked for scrap. In 1962 the Gresley A3 Preservation Society was established to raise funds to save the locomotive but in the event they could not match the £3,000 asking price.

However, a wealthy businessman by the name of Alan Pegler stepped in and acquired the locomotive. He secured a remarkable deal from British Railways allowing him to overhaul, repaint and stable Flying Scotsman at Doncaster Works as well as securing the rights to operate the locomotive on the main line (Pegler et al, 1970).

The nostalgic Flying Scotsman and Britain’s ‘cult of the past’

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/160507/003Pegler’s acquisition of Flying Scotsman helps illustrate wider emerging themes in the 1960s concerning nostalgia and the preservation of the past. The ‘increasing cult of the “national heritage”’ was a largely British phenomenon leading, as David Cannadine has noted, to ‘unbridled (and often uninformed) nostalgia’ (Cannadine, 2002). Pegler himself was an avowed nostalgic and proud of Britain’s engineering heritage. In 1954 his investment ensured the longer term survival of the recently reopened tourist line the Ffestiniog Railway in Wales and he further raised his profile by organising a number of special charter trains hauled by historic locomotives. His rescue of Flying Scotsman not only increased his profile in heritage railway circles but now gave him national exposure. In January 1969 he appeared on the popular BBC radio programme Desert Island Discs.[10] The presenter Roy Plomley asked if he had chosen his records ‘nostalgically’. Pegler confirmed that he had: ‘I would like from a nostalgia point of view to recapture memories of earlier days.’ He was, he continued, ‘unashamedly a terrific sentimentalist…’. It was a subject he would turn to again when choosing his final record ‘When Britain Really Ruled the Waves’ from Gilbert & Sullivan’s opera Iolanthe: ‘I make no bones at all about being a sentimentalist and I make no bones at all about being, I suppose, very patriotic… I love England and I am proud that I’m English. I know that all these things are very unfashionable these days but nevertheless I do have these feelings…’

The 1950s and 1960s may have been decades of great change but they also witnessed a growing interest in preserving Britain’s social and industrial heritage. This was seen in the work of people like the museum director Frank Atkinson who strove to establish an open air museum in the North East of England in order to prevent the loss of ‘everyday material’ (including machinery) and present it ‘on a vast scale before it was too late…’ (Atkinson, 1999). Beamish would eventually open in 1971 but not after Atkinson had faced considerable opposition from those ‘who disapproved of the idea of an open-air museum in general and of industrial heritage in particular’ (Brown, 2009). Similarly, the engineer and writer Tom Rolt had focused on preserving canals and railways and the ways of life associated with them. In the 1940s he founded the Inland Waterways Association and the Talyllyn Railway Preservation Society, leading to the preservation of many derelict canals and inspiring the railway preservation movement.[11] The impact of the work of Rolt, Atkinson and others on focusing attention on often neglected areas of Britain’s heritage should not be underestimated.

In 1974 the Victoria and Albert Museum’s Director Roy Strong remarked on the wider appeal of Britain’s heritage as representing ‘some form of security, a point of reference, a refuge perhaps, something visible and tangible which, within a topsy and turvy world, seems stable and unchanged’.[12] The phenomenon was nothing new. Industrialisation and the growth of Empire had led to significant changes to British ways of life in the nineteenth century too. The fashion for ‘restoration’ of historic buildings to an appearance they had never actually had led William Morris and others to form the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings in 1877. It is with this movement that the phrase ‘a national heritage’ – the notion that historic buildings were an inheritance to be protected – started to be widely used.[13] The notion would spread beyond the built heritage to other historic survivals too, physical, cultural and spiritual. This pattern was certainly seen in the 1950s and 1960s, a time which witnessed a great rise in the number of preservation societies ranging in diversity from the Victorian Society (1958) to the Society for the Preservation of Beers from the Wood (1963). The mood was captured perfectly in popular music such as the Beatles’ Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967), with its music hall inspirations, and more overtly through the Kinks’ 1968 album The Kinks are the Village Green Preservation Society. On the album’s title track ‘The Village Green Preservation Society’, the band’s lead singer and songwriter Ray Davies damned office blocks and skyscrapers whilst eulogising ‘Tudor houses, antique tables and billiards‘. The Kinks may have been part of the cultural revolution of the 1960s that men like Alan Pegler found so unsettling but these were sentiments that he could easily relate to. As Davies plaintively sang: ‘Preserving the old ways from being abused… What more can we do?’

A growing sense of nostalgia was seen in other aspects of popular culture at this time, from the renewed interest in the music of Gilbert & Sullivan (Pegler and Harold Wilson were fans) to the television programme Dad’s Army, which nostalgically looked back to a recent but swiftly vanishing past (the programme was first broadcast less than a fortnight before that last British Rail main line steam run in 1968). Preservation, nostalgia and a pride in the past were not just seen in popular culture or the emergence of new preservation societies. The most significant heritage body at this time was the National Trust. Established in 1895 the Trust began in the 1960s to move from its pre and post war focus on acquiring country houses and estates to engaging with the wider social and economic heritage of Britain. In 1963 the Trust decided to extend its preservation to industrial monuments, including canals and railways. This was in large part due to the work of Rolt and others and was a huge shift in focus from an organisation that had emerged in the late nineteenth century as a response to the Industrial Revolution which had hitherto been viewed as ‘an unmitigated disaster’ (Cannadine, 2002). This change of emphasis chimed with the national mood and membership swelled from 23,403 in 1950 to 157,581 in 1965 (rising to over 539,000 in 1975) (Cannadine, 2002 p 235; Newby, 1995). During the late 1950s and particularly in the 1960s, railway preservation – with its roots as far back as the 1840s – also enjoyed a huge surge in interest as people responded to the introduction of new technology, the imminent ending of steam hauled operations and the closure of nearly six thousand miles of railway track.

Preservation societies were formed to secure the long term future of representative examples of steam locomotives and to reopen branch lines as heritage attractions. The first of these, Rolt’s Talyllyn Railway Preservation Society, had been founded in 1949 but it was in the 1950s and 1960s that the movement enjoyed its most significant growth. This rise in interest led to the formation of the Association of Railway Preservation Societies (ARPS) in 1959 with a remit to co-ordinate the activities of the various societies. The ARPS grew to have over 100 member groups (Biddle, 1997). The first closed British Railway’s branch line to reopen was the Bluebell Railway in Sussex in 1960. Many of today’s best known preserved railways, such as the Keighley & Worth Valley, the Severn Valley and the North Norfolk were set up in this decade. Moreover, the proposals to demolish significant pieces of railway architecture and infrastructure attracted a more varied audience also, notably Nikolaus Pevsner, the most prominent architectural historian in the land, and fellow members of the Victorian Society, including Britain’s most popular living poet, the well-known rail enthusiast John Betjeman.

For the architectural preservationists the controversial destruction of the celebrated Euston Arch in the early 1960s – an act of ‘malice and philistinism’ according to one architectural historian (Stamp, 2007) – particularly galvanised the Society. In 1964 the Society had presented to the Ministries of Transport and Housing and Local Government a list of sixty railway stations ‘specially worthy of preservation because of their architectural merit or historical interest’ (Stamp, 2010). In 1967 the Society played a crucial role in preventing both London’s King’s Cross and St Pancras stations from being demolished and rebuilt as a unified station in modern brutalist fashion (Stamp, 2010). Such high profile campaigns saw membership of the Society rise from a mere 28 in 1958 to more than 1,800 by 1970 (Filmer-Sankey, 1998). The interest in railway preservation wasn’t confined to historic railway architecture and routes. As British Railways’ modernisation programme gathered pace so the future of celebrated steam locomotives became more uncertain. Not only that but long established locomotive building works began to close after struggling to adapt to the production of the new diesel and electric locomotives, including such famous names as Gorton, Beyer Peacock and the North British Locomotive Company (Kynaston, 2015). The end of steam was becoming reality.

British Railways did inherit a responsibility for an historic collection of locomotives and other railway artefacts displayed in the British Transport Commission’s museum in Clapham, which opened in 1962–63. This did not sit easily with a company trying to project a modern image and Beeching sought to ‘dispose’ of the collection. Concerned by this move various senior transport experts, including the President of the Stephenson Locomotive Society, the Chair of the Consultative Panel for the Preservation of British Transport Relics and the past President of the Newcomen Society, sent a letter to The Times in August 1964 arguing that the country’s main transport museums should be brought under the Department for Education and Science as the only way ‘to ensure the continued maintenance of these collections, which are beyond doubt a vital part of our national heritage’ (The Times, 1964). Such pressure helped lead to British Rail transferring responsibility for these historic railway artefacts to the Science Museum as part of the 1968 Transport Act, in turn leading to the creation of the National Railway Museum (NRM). But this was not all. As well as the Gresley A3 Preservation Society the 1960s saw a number of similar groups emerge to secure the preservation of significant locomotives not earmarked for the National Collection. Amongst the societies established were the Princess Elizabeth Preservation Fund (1963), the Sir Nigel Gresley Locomotive Preservation Trust (1965) and the East Anglian Locomotive Preservation Society (1967). The preservation of locomotives and lines relied heavily on a huge band of dedicated enthusiasts and a small number of private individuals like Pegler and Billy Butlin, who acquired eight locomotives to display at his holiday camps, including the ex-LMS Pacific Duchess of Hamilton now in the National Collection (Gwynne, 2011). Here the ARPS, under the chairmanship of Peter Manisty, was also extremely important in negotiating with BR for member societies to ‘make their bids for B.R. relics which could not be accommodated in the national and publicly-owned museums’ to ensure that ‘nothing is left in steam which the next generation will miss’ (Railway Magazine, 1968).

The modernisation of Britain’s railways can therefore be argued to have had a profound effect on the railway preservation movement. In response to the end of steam Betjeman, long known through his radio broadcasts and poems for his love of all things railway, wrote and narrated Railways For Ever!, a documentary produced by British Transport Films and featuring the last British Rail steam hauled service in August 1968. The poster advertising tickets on this train, titled ‘British Rail runs out of steam’, also played the nostalgia card promising as it did ‘314 nostalgic miles, 10 ¾ happy hours’ (Gourvish, 1986). The occasion was of such moment that ‘police and staff had difficulty in controlling the crowds’ while the driver and fireman signed autographs for hours after the train had terminated (The Times, 1968). Once again The Kinks captured the mood in their 1968 song ‘Last of the Steam-Powered Trains’. Railway preservation was becoming an integral part of Britain’s national heritage. In May 1968 Flying Scotsman even hauled a charter train in aid of the ‘Save HMS Victory Fund’ and the National Trust’s Enterprise Neptune scheme (Railway Magazine, 1968).

The conflict of preserving the past

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/160507/004Given that the preservation of operational steam locomotives was in its relative infancy in the 1960s there were no clear guidelines in place to help owners address the conflict of conservation over restoration – the big debate that, as we have seen, erupted in the late nineteenth century concerning historic buildings. As a private owner Alan Pegler enjoyed complete freedom over how to present Flying Scotsman as a preserved locomotive. The Railway Magazine was quick to recognise this: ‘The pros and cons of the preservation of this particular Pacific do not enter into this case, as this was one man’s personal choice, and who can question it? When the famous locomotive steamed out of Kings Cross on Monday, January 14, it was a sad day for many but at least it was not heading for the scrap heap’ (Railway Magazine, 1963). From the nineteenth century steam locomotives had largely – with some notable but only occasional exceptions – been preserved as static objects but Pegler, who as a member of British Railway’s Eastern Region Board had inside knowledge of the railway system, wanted to ensure that Flying Scotsman would both remain operational and – despite the impending steam ban – continue to run on the main line. He was open about his intentions: ‘I intend to preserve it in working order. In a way, it will be a monument to the skill of the local [i.e. Doncaster] craftsmen’ (The Times, 1963).

As with many forms of nostalgia Alan Pegler’s rationale was rooted in his own childhood when he had first seen Flying Scotsman as a static object at the 1924 Wembley Exhibition and then again a few years later, in 1928, at speed hauling the new non-stop ‘Flying Scotsman’ train:

Looking back I sometimes wonder whether this was what first forcibly brought home to me the difference between a cold steam locomotive and a hot one; a dead one and a live one. There seemed to be no connection between the showpiece inside an exhibition hall and the beautiful piece of machinery with its huge, striding wheels, flashing rods and plumes of smoke and steam at the head of the train.

Pegler, 1970

Pegler’s determination, inside knowledge and negotiating skill saw him secure a deal from the British Railways Board to run Flying Scotsman on the main line until 1966, an arrangement subsequently extended until 1971 (Pegler, 1970). This was to prove crucial in further enhancing Flying Scotsman’s profile, as Pegler explained:

Suddenly, therefore, it appeared as though 4472 was going to be the only privately-preserved main-line steam locomotive anyone was going to be able to see or travel behind… In fact when British Railways had themselves run their own last main-line steam tour on August 11, 1968 it became a fact that 4472 was the one and only in Britain.

Pegler, 1970

Alan Pegler’s motives were ones with which many clearly empathised but not everyone approved. One outspoken critic came from an unexpected quarter. Marjorie Gresley, daughter of Flying Scotsman’s designer Sir Nigel Gresley was quoted in The Times as saying she ‘would prefer to see the locomotive given a dignified retirement than exploited on runs to Scotland. I feel sure this is what my father would have wished… It is a personal thing with me. I have been invited to go on these jaunts, but have had to refuse.’(The Times, 1968) The conflict of preserving an object that was designed to be operated is one that has troubled museum curators for many years. This was due largely to the problem of conveying the significance of an item when the context of its very existence had changed completely. Questions of practicality, cost, maintenance and, ultimately, authenticity were, and are, key factors also. As Professor Jack Simmons would later write: ‘’Restoration’ is itself a term of controversy, often involving delicate and difficult decisions. Locomotives, for example, seldom remained entirely unaltered throughout their working lives. When one comes to be preserved, should it be kept exactly as it was when taken out of service, or should it go back as far as possible to its original condition?’ (Simmons, 1981).

Pegler’s treatment of Flying Scotsman is contrasted by that of another star LNER locomotive, the world steam record holder Mallard. Upon withdrawal from service in 1962 Mallard became part of the National Collection and was restored to her appearance at the time of her world-beating run in 1938, including full repaint in LNER colours, replacement (or more accurately replication) of sections of her streamlined casing that had been removed during the Second World War and renumbering to her original number of 4468. Shortly after her 1938 record was achieved Mallard’s original tender was replaced by one of the different connecting corridor type. In restoration she was to be reunited with a restored non-corridor tender, but not the original. Mallard’s mechanical parts, including boiler, were retained in their ‘as withdrawn’ condition. However, externally the locomotive, intended as a static museum piece, had a restored, rather than conserved, external appearance. Apart from a brief return to main line steam in time for the fiftieth anniversary of her most famous feat in 1988, Mallard has remained a static museum object. Indeed, it was only in 1988 that the NRM first took the decision to conserve rather than restore a rail vehicle accessioned into the collection.[14]

With the operation of Flying Scotsman being Alan Pegler’s declared aim the question of how to present his locomotive was also addressed. As with Mallard many other preserved locomotives by this stage had been restored to the look that they had at the time of their greatest achievements.[15] Similarly, it was believed that Pegler’s intention was to restore Flying Scotsman – a locomotive which had undergone numerous alterations in the forty years since she was constructed in 1923 – to its most famous condition. What that condition was would be hard to define given the various notable events in the early history of that locomotive, which had been interspersed with changes to its appearance. The popular view on Flying Scotsman was that she would go back to her classic LNER appearance (despite no-one pinning down exactly what that should mean). This aim was clearly believed by railway media and enthusiasts, the Railway Magazine for example noting that it was ‘being restored…to its earlier condition, as L.N.E.R. “A1” No.4472’ (Railway Magazine, 1963). This was certainly the popular perception. In Awdry’s Enterprising Engines, Flying Scotsman tells Gordon: ‘I had a rebuild…and looked hideous. But my Owner said I was an Extra Special Engine, and made them give me back my proper shape.’[16] However, at the time of Alan Pegler’s acquisition Flying Scotsman looked considerably different to how she appeared in her various pre-War guises. Such have been the changes that in her lifetime Flying Scotsman has had three different classes (A1, A10 and A3), three different styles of dome and chimney, four different liveries, six numbers (1472, 4472, 502, 103, E103 and 60103), nine different tenders and fifteen different boilers (McLean, 2015). When Alan Pegler acquired the engine he also acquired spare parts from other A3 Pacifics, notably a locomotive named Salmon Trout and many of those parts are now in use on Flying Scotsman itself (Coulls, 2015). It was common practice for parts from other locomotives to be removed and put to use on other engines during routine overhauls – Flying Scotsman was no different to any other locomotive in this respect.

It would have been extremely difficult and costly to return Flying Scotsman to one of her various appearances from her 1920s and 1930s heyday. Pegler recognised the fact stating that it was ‘out of the question to consider trying to convert the locomotive to her original condition’. Instead he settled for a more ambiguous solution which he called ‘a typical LNER A3 of the 1930s’ (Pegler et al, 1970). Pegler may have been a nostalgic but he was practical too. With numerous changes in appearance over the years, and the desire to have something approximating its 1930s appearance recreated, inevitably it meant that Pegler’s 1963 ‘restoration’ was something of a compromise. Further changes were made during the 1960s – some subtle, such as variations to the apple green livery, others less so, most notably the addition of a second tender to carry extra water on longer journeys (a response to the removal of the infrastructure that enabled steam locomotives to operate on the main line). The consequence has caused confusion ever since with people associating the 1963 restoration with Flying Scotsman’s original appearance, encouraged further by the huge popularity of the Hornby model of the preserved Flying Scotsman that was on sale in the 1970s.[17]

However, as we have seen, the principles of conservation were already well established concerning the restoration of historic buildings. Such principles did not concern the railway preservation movement and restoration to an idealised state has been for many years the accepted practice. This was equally true of Flying Scotsman which had its later 1920s-style single chimney and LNER apple green colour scheme restored along with being united once again with a corridor tender, a style it had last used in 1936. However, all other aspects of Flying Scotsman’s 1947 and 1953 rebuilds were retained thus giving the locomotive an appearance it had never before carried. For Pegler a compromise was enough as long as certain core elements of his locomotive’s pre-Second World War appearance could be restored.

The significance of the number 4472 was key to Pegler also. Flying Scotsman may have carried several different numbers in its career but for its key achievements up until that point – the Wembley Exhibition, the non-stop runs, the Flying Scotsman movie and the 100mph speed record – she had carried the number 4472. For Pegler this number was synonymous with the locomotive and when talking about his engine he would typically call her ‘4472 Flying Scotsman’, the number always preceding the name. Again he harked back to his youth, to the time when he first fell in love with this engine. ‘The first non-stop “Flying Scotsman” run,’ he would reminisce, ‘got a great deal of publicity, and every photograph that was published seemed to show the same engine as if there were no other – No.4472.’ Pegler’s recollections were accurate – although other locomotives would be used in the LNER’s publicity none appeared as frequently as Flying Scotsman. To Alan Pegler this number was special: ‘Nationalisation after the war,’ he wrote, ‘seemed to me, at the time, to be the ultimate disaster as even magic numbers like 4472 disappeared’ (Pegler et al , 1970). Ironically, Flying Scotsman had already lost the number seven years before nationalisation.

With compromises made Flying Scotsman underwent a full overhaul at Doncaster works and re-emerged resplendent in its new guise on 26 March 1963, just three months after being withdrawn by BR.

The following day Beeching’s report The Reshaping of British Railways was issued leading to a fierce reaction and much public opposition, such was the sentimentality ‘attached to the railways as the symbol of Victorian enterprise’ (Sandbrook, 2006). The timing of Beeching’s report must have been fortuitous for the success of the now preserved Flying Scotsman, which became an immediate and spectacular success. Flying Scotsman’s first public passenger carrying run on 20 April 1963 from London’s Paddington Station to Ruabon attracted great public and media attention despite heavy rain, with several thousand turning out at Birmingham’s Snow Hill station to see Flying Scotsman’s debut as a preserved engine. So dense were the crowds that one of Pegler’s inner-circle Trevor Bailey compared the scene to resembling ‘the terraces of Wembley Stadium on Cup Final day’ (Bailey, 1970). As the popularity of the locomotive surged so too did its ‘old’ (but actually new) appearance cement itself into the public consciousness as the way that Flying Scotsman was meant to look.[18]

Modernity versus nostalgia

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/160507/005With Flying Scotsman ‘restored’ and operational, the locomotive became – as evidenced by her 1966 Blue Peter appearance, the 1968 documentary and the Reverend Awdry’s children’s stories – a nostalgic symbol. But it would be too simplistic to say that Britain was only interested in the railway past. Indeed 1968 hadn’t just witnessed the end of steam but it was also the year in which the British Railways Board was finally given the go ahead to push on with the revolutionary Advanced Passenger Train (APT) project (Baily, 1968). This project aroused interest from across the world as it proposed developing a train capable of speeds of 155mph and being able to tilt on conventional tracks (an idea of developing hover trains was quickly dropped when the APT project became reality). The Times was enthusiastic and, as he explained on Desert Island Discs, Alan Pegler was supportive (Baily, 1969). Nevertheless the legacy of that period tends today to be viewed through the fog of nostalgia focusing on the end of steam while the optimistic future has been largely forgotten. This was in part due to the hollow nature of Wilson’s ‘white-hot technology’ vision – APT suffered from the start from much government indifference. As one of the APT project team Hugh Williams has written, part of the reason the project was dogged by problems was a succession of Governments ‘turning the investment tap on and off at will’ (Williams, 1985). Indeed the relatively Spartan budget of the APT project (approximately £40 million from 1968 until 1984) did not compare favourably to the other great British transport innovation of the 1960s, the joint development of Concorde with France, on which £2 billion was spent between 1967 and 1976 (Wickens, 2008). The partnership of the two countries on the supersonic plane contrasts with their respective attitudes to High Speed rail.

APT, therefore, was poorly funded but it even faced opposition and indifference from within BR itself, due in large part to the project seen as being run by ‘an expanding Research department staffed by non-railway personnel’ (Williams, 1985, pp 109–111). Contrast this with the French High Speed TGV project which received full government and industry backing. It was true that the BR Research Department was staffed with a large number of people from a non-traditional railway background, most notably Alan Wickens, a graduate of Loughborough University who joined the department in 1962 from the aerospace industry (Williams, 1985 p 8). Wickens would undertake world leading research on High Speed rail but his name is largely unknown in the UK. This indifference can in part be put down to established senior railway figures failing to move on sufficiently from the end of steam, a problem perhaps best highlighted through the problems APT faced with ASLEF, the Trade Union for locomotive drivers. APT had been designed as a one-man operation but ASLEF, which had been set up as the union for steam locomotive drivers and firemen in 1880, blacked the new train and insisted the cab be crewed by two men. This ludicrous situation lasted for some time, causing significant delays to the development of a truly ground breaking and innovative train on the basis of steam era operations, an example of how a fixation on the past caused significant damage to innovative and forward thinking in the UK rail industry (one-man operation posed no difficulties for the TGV) (Williams, 1985 pp 34–37 and 111).

From the beginning APT had not received strong enough backing by Wilson’s government in the late 1960s. Despite all the talk of ‘white heat’ the railways continued to receive poor levels of investment. The modernisation programme begun in 1955 and the ‘reshaping’ of the railways as instigated by Beeching in 1963 may have been continued by the Labour government but there seemed to be no real coherent scheme for the railways. In December 1964 it was announced that Beeching, who had been appointed by the previous Conservative Government, would not be taking charge of a survey into the integration of the British transport system which Tom Fraser, the Minister of Transport, wished to complete (The Times, 1964). This snub was captured by the Daily Express cartoonist and arch Wilson critic Cummings in a cartoon showing Beeching disembarking from an ancient looking train, with the Prime Minister, standing on the locomotive footplate, calling after him: ‘You don’t realise, Dr Beeching, that what we need is a Gothic railway system – as George Stephenson intended.’ The train was headed by an antiquated locomotive with the slogan ‘Modernise with Labour!’ painted on the tender. The name of the train was painted above one of the wheels: ‘The Flying Scotsman’ (Daily Express, 1964). Beeching left British Rail shortly afterwards claiming that he had resigned with the government happy to give the impression he had been sacked. Four years later Beeching would stand up in the House of Lords and dismiss the APT project as ‘no more than a gimmick’ (Baily, 1969). Moving Britain’s railways forward was clearly not going to be easy.

The conflict of modernity versus nostalgia is further seen in Pegler’s most audacious Flying Scotsman stunt when his locomotive became the figurehead of a mobile UK trade mission to North America in 1969. The tour was to take in ten American cities starting in Boston and work its way across America with Flying Scotsman at the head of a train (accompanied at various points by two Routemaster buses) featuring numerous hackneyed British cultural referencing points including Beefeaters, a Churchill impersonator (played by Churchill’s own nephew John Spencer Churchill), a Pipe Band Major (to ‘entertain crowds during many of the stops’), ‘a bevy of attractive young Englishwomen to handle souvenir sales’ (each dressed in tartan mini-skirts), an Old English tavern (named ‘The Fireman’s Rest’), a butler (supplied by Fortnum & Mason) and, perhaps most bizarrely of all, a man dressed in a full suit of armour (Edmonson, 1970). However, the trade fair did not sit easily with many in the UK. Some businesses shunned it as being too ‘gimmicky’ with The Times asking ‘is this really doing much to promote the image of Britain as a major technological industrial nation, able to compete in America’s razor sharp markets?’ As one Philadelphian businessman remarked: ‘We all go for the English tradition bit…but the only way to sell me machine tools is with an expert salesman and a fine product.’ Flying Scotsman’s ‘unique British American trade mission’ gets to the root of the dichotomy between contrasting what The Times called the ‘Traditional Britain’ image with the desire of Harold Wilson’s government to show Britain as a modern country at the forefront of new technology and innovation (The Times, 1969).[19]

Flying Scotsman’s North American tour proved to be the culmination of Pegler’s remarkable ownership of the locomotive. The trip ended in his own financial ruin with his beloved ‘4472’ impounded by the American authorities.[20] Alan Pegler would return to the UK where he was declared bankrupt. In the official receiver’s report into his application for discharge from bankruptcy it was noted that his continued sinking of his funds into the tour was prompted by ‘his unbounded enthusiasm for the Flying Scotsman.’[21] He was discharged in the Bankruptcy Court in 1974, expressing no regrets for getting involved with Flying Scotsman. As The Times reported:

After the hearing the great locophile, a cheerful engaging man in mutton-chop whiskers, penniless but unbowed said: ‘I do not regret buying the Flying Scotsman. It was the chance of a lifetime, and I would have kicked myself if I had not taken it.

Of course, I cannot say that I do not regret losing all my money, my house, my country house, my flat in Italy, my Bentley and my Volvo, and being left only with what I stand up in. But life is about taking the rough with the smooth.

He looked less like a man eaten with regret, than somebody still entranced by the distant vision of a great steam monster puffing over the Cheviots. The Flying Scotsman…is at present stabled at Carnforth, a permanent challenge and temptation to romantic railway visionaries.

Conclusion

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/160507/006Alan Pegler retained his affection for Flying Scotsman up until his death in 2011. So powerfully did he shape the profile and image of Flying Scotsman that his compromised and historically inaccurate ‘restoration’ of 1963 has embedded itself on the consciousness of so many enthusiasts as the only ‘correct’ appearance of the locomotive. This appearance had finally changed in the 1990s when the double chimney, smoke deflectors and BR livery had been restored. Later the locomotive would be painted apple green and the number 4472 reinstated but the double chimney and deflectors remained (the greater efficiency these gave at a time when the locomotive was being heavily operated being the reason given). It was thus as a strange hybrid that the National Railway Museum acquired Flying Scotsman in 2004. The numerous complaints this prompted showed how closely people mistakenly associated her 1920s appearance with Pegler’s 1960s restoration. As one letter received by the museum on the subject in March 2005 put it:

Please settle an argument. We watched a programme on TV about the “Flying Scotsman” running to York & Scarborough. What happened to the original one (the one without deflectors, single funnel only the original 4472 owned by Pegler. Not this “pretender” in your museum. I [am] sure I have seen the same loco in Swanage (not the original one). People keep saying this is the “Flying Scotsman”, its not…[22]

It is perhaps no surprise, therefore, that the NRM’s 2015 decision to restore the locomotive to as close to its final BR appearance as far as practicable was met with howls of complaint. The restoration, concluded in 2016, is also a compromise in order to satisfy modern safety requirements and accommodate later alterations to the engine that cannot easily be changed. The question of her appearance remains an emotive subject but Flying Scotsman, now the oldest working main line steam locomotive in Britain, has always been something of a chameleon. As a preservation trailblazer the spirit of Flying Scotsman is very much tied up in its story post preservation: it is the period in which an idea of what this locomotive is and what it stands for – even if misrepresented – was cemented and is today a key factor in its overall significance and popular perception as ‘the most famous steam locomotive in the world’.

Tags

Footnotes

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text