A museum by the people for the people? A review of St Fagans National Museum of History’s new galleries

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201304

Keywords

Activist Museums, Community Engagement, Exhibition review, museology, National museum, Social Engagement, Socially Engaged Practices, St Fagans, Wales

Introduction

What do our museums do for us? The public is long familiar with museums as spaces of preservation, education and inspiration – where histories are cared for, learning is ignited and days out are enjoyed (BritainThinks, 2013, p 3). Few would dispute these roles, but should museums be having an impact on broader concerns in our lives? The last decade has seen a shift in the sector towards a more active role in wider society, something Manchester Art Gallery’s director, Alistair Hudson (2017), captured:

It is vital now, post-crash, post-politics, post-Brexit, that our cultural institutions reconnect with the world, not as escape capsules, not as commentators or documentarists, but as active centres of social learning and making.

Hudson calls on museums to start doing something for society. Not simply recording and relaying information, nor just providing a nice day out, but to use and expand their work to support communities more directly and impactfully.

In 2010, Nina Simon’s Museum 2.0 concept put participation at the forefront of museum concerns. Simon asserted that museums should aspire to be physical places ‘where visitors can create, share, and connect with each other around content’ (2010, pp ii). She called for museum displays made ‘with’ not ‘for’ communities, which has subsequently been reflected in the practice of many UK museums. High-quality and compelling exhibitions have been co-created with constituents, such as Beyond Dementia, 2017, at The Whitworth, and Who Decides?, 2018, at National Museum Cardiff.

As the 2010s progressed, focus on participatory work transformed into an altogether more socio-politically motivated movement within museums, reflecting Hudson’s call to action above. Robert Janes and Richard Sandell term this kind of institution the ‘activist museum’, one which goes beyond Simon’s museum-centric issues of participation and inclusion, towards an awareness and responsiveness to the needs, aspirations, challenges and misfortunes within wider society (2019, p 1). Activist museums are framed by Janes and Sandell as civic institutions, prepared to look outwards, away from traditional museological issues, to offer practical solutions to pressing political, social and environmental concerns faced today.

St Fagans National Museum of History

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201304/001Situated near Cardiff, St Fagans National Museum of History is not an obvious candidate for an activist museum. First opened in 1948, the Museum set out to represent the lived experience of the Welsh through a selection of historic buildings, plucked from their original locations across the nation and rebuilt in its idyllic grounds. It is now one of Wales’ most popular visitor attractions, and for many who grew up in Wales, like me, it is a place of fond school-trip memories where one entered a strange, but familiar, mini historic Wales.

In 2018, the Museum completed its six-year ‘Making History’ redevelopment project, which saw £30 million invested in improved education facilities and new exhibition spaces. In their essay included within Janes and Sandell’s edited volume, Museum Activism, St Fagans curators Sioned Hughes and Elen Philips emphasise that the project allowed not only for physical changes, but for a conceptual redevelopment towards becoming an activist museum (2019, p 245). For St Fagans, activism is framed as being a museum working with rather than for its communities – working more collaboratively to form a democratic model for museums which benefits interests beyond those of the curators and conservators. One example during the project is the Museum’s apprenticeship scheme with the redevelopment contractors, one way of ensuring direct community benefit by offering people skills and employment.

As they explain, this ambition is present within the Museum’s history, as its founder, Iorwerth Peate, was keen for St Fagans to not simply preserve the past, but to benefit the welfare of future communities (Peate, 1948). This forward-thinking approach mirrors the aims of the (Wellbeing of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015), which requires Welsh public bodies, including national museums, to frame their objectives against the Act’s aims of sustainable economic, social, environmental and cultural development in Wales. As such, St Fagans’ activist approach during and since the ‘Making Histories’ project derives from both an internal ambition, as well as wider political initiatives, towards improving lives in Wales.

Being familiar with St Fagans as a place of nostalgia I am keen to see how, now that the ‘Making History’ project is complete, the Museum’s ambition to be forward thinking, through activist and democratic approaches, translates into the general visitor’s experience. For my visit, I will focus on the newly redeveloped gallery spaces – Life Is, Wales Is and Gweithdy. Though much behind-the-scenes work has been conducted, will St Fagans be able to clearly present activist ideas, and a democratic approach, within the most traditional aspect of any museum: the exhibitions?

Byw a Bod/Life is...

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201304/009In this large and light gallery space, we’re given a sweeping history of day-to-day life in Wales, structured through themes: ‘Looking Good’, ‘Food’, ‘Work’, ‘Fun’, ‘Bed’, and ‘Death’. This gallery, and its neighbour, Wales Is, are situated within the modern entrance hall, offering a look at artefacts before you embark into the open grounds. What is striking after visiting this gallery is the sense of balance maintained throughout – I was left feeling that I had gained a detailed look at aspects of Welsh life through the centuries, but not been bombarded or overwhelmed with facts and figures.

Objects are familiar, even if ancient, such as gravestones with epitaphs for Roman Britons, or medieval bowls and cutlery. It is the personal touch, however, which brings life to objects that are, by their nature and without context, every-day and unextraordinary. Labels for items of clothing always detail their significance to the former owner – whether it was a cloak worn by Ella Thomas to her uncle’s funeral, or a jacket used for dancing by a Teddy Boy. Short and engaging quotes, from contemporary sources, give an insight into peoples’ feelings and experiences, and makes me, as the visitor, feel as though I am bypassing curators and being spoken to directly from the source.

It is through these real-life vignettes, and their relatability, that the democratic aspect of Life Is becomes most clear. Woven into each display theme are stories from staff, and from patients with learning disabilities and mental health problems, living at Bryn-y-Neuadd hospital in Llanfairfechan. We learn about the importance of tea made in the hospital, and of happy marriages between patients. There is little fanfare or fuss around the inclusion of these stories from a historically marginalised group, which could so easily be ‘othered’ within a special exhibition case or be made to seem like a temporary ‘takeover’. The stories of Italian migrants, Bryn-y-Neuadd patients, nineteenth-century widows and coal miners are all part and parcel of the Welsh story, each being offered a chance to ‘speak’ on an equal footing.

In Life Is, a democratic approach is clear in its inclusion of a variety of non-curatorial voices, both past and present, allowing people to speak for their own experiences. This tackles the museum-centric issue of better representation within interpretation. But, despite the title being in the present tense, I found it difficult to make a link between what was displayed in Life Is and how it could impact issues with work, food and sleep in Welsh lives today. Whilst succeeding in making the past active, I found little evidence of an activist approach for today.

Wales Is...

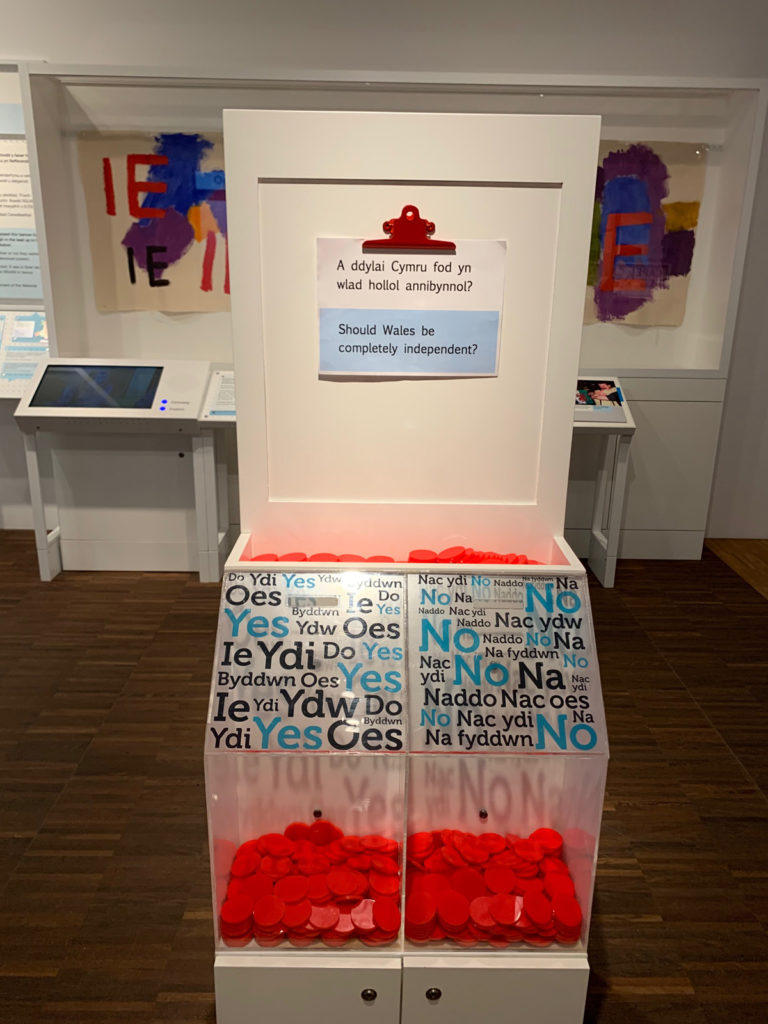

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201304/010The gallery next door tackles the knotty question of what Wales Is. This is a much smaller space than Life Is, with a low ceiling, little natural light and a clean whitewashed look, contrasting with the colour and scale of its neighbour. There are several topics on display, each visually and thematically distinct from one another, aided by the clean arrangement of vitrines and information boards into a grid-like formation. Amongst the topics, curators have suggested that Wales is ‘musical’, ‘partly Roman’, ‘2% Neanderthal’, ‘Llywelyn and Glyndŵr’, ‘independent?’ and even ‘not always welcoming’. Despite being wide-ranging, the themes are treated individually, meaning the gamut of Welsh history and identity is digestibly presented through short-and-sweet standalone topic zones. Themes are given more in-depth exploration through simple but thought-provoking activities throughout the gallery, which imbue the space with a laboratory-like feel.

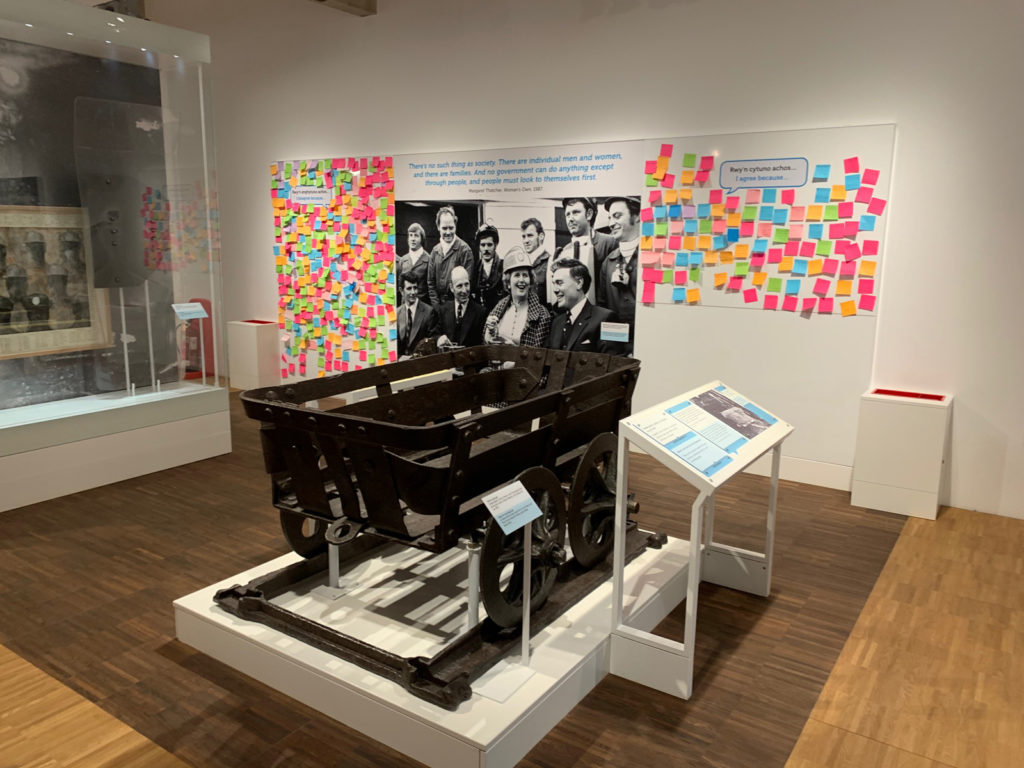

The most striking activity sits within a cluster focusing on coal mining. This is amongst the most obvious topics for a museum on Welsh history, a country proud of its industrial heritage, but St Fagans approaches it from an unexpected angle. Behind a blackened coal cart is a large picture of former Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, laughing amongst smiling miners. The mere inclusion of such an image is of interest due to Thatcher’s divisive reputation in South Wales’ coal mining communities, where she was reviled after the closure of the pits during the 1980s and the loss of 25,000 jobs (BBC News, 2014).

Above the image is one of Thatcher’s most famous and controversial quotes, and to either side the Museum asks whether visitors agree or disagree with her statement, and why. With this prompt the whitewashed walls are interrupted by a blaze of Post-it notes, so many that gallery invigilators tell me they struggle to replenish them quickly enough. On either side, visitors have passionately written arguments for or against in bold capitals, underlined words or long, carefully thought out statements. It’s clear from the handwriting that nearly all ages have engaged, and some have even crossed out others’ comments, or added their own arguments. Situated next to this debate, the coal cart gains greater emotive complexity as an artefact of an industry now gone, and one is left to contemplate the wider social and political implications of coal mining, its decline, and Thatcher’s impact.

This format is reflected in topics across the space, for example by a case exploring the medieval Welsh Age of Princes, which asks if Wales should be a ‘Republic or Monarchy – What do you think?’. Objects spanning millennia of Welsh history are revitalised, made thought-provoking and relevant to contemporary concerns by the inclusion of sometimes provocative questions. The visual impact of the brightness of the Post-it notes, and the volume of responses, means that public opinion is the most eye-catching element in the entire gallery. Curatorial authority has gracefully taken a step back and has, by skilful design, encouraged confident debate around complex issues spanning the nation’s history, allowing Wales to speak for itself.

Consequently, this is where an activist and democratic approach is at its clearest and most powerful. Visitors’ opinions are privileged above the Museum’s, and there is a sense of the space being social and open to diverse thought and experiences. What isn’t clear is the bigger-picture outcome beyond the Museum for the opinions gathered here. Reaching back to Janes and Sandell, for St Fagans to be truly activist, might there be a way that these opinions on socio-political issues could have a tangible impact, perhaps by being catalysts for Welsh Assembly debates, or using the platform to crowd-source solutions to community problems? It is a room buzzing with energy, and a testament to St Fagans’ democratisation work, but have they squeezed out all the exciting potential from this interactive format?

Gweithdy

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201304/011

The last gallery on my visit is no less impressive. Gweithdy (‘workshop’ in Welsh), set away from Life Is and Wales Is, nestled within St Fagans’ grounds, is a multipurpose space: part gallery, café and active workshop. The displays are a celebration of Welsh makers, presenting a wide range of objects from a vast time period, arranged by material (such as wood or textile). The focus throughout is on the development and application of skill and creativity, and this feeds into the beautifully made interactives, simply designed but attractive to touch and try for adults and children alike. Despite the impressiveness of the display, while alone in the room on a Monday in December I feel that I am visiting at too quiet a time to see Gweithdy’s full potential. The active workshop isn’t running during my visit, and there’s nobody about to play with interactives, but I can see how as a space of learning and making, Gweithdy is brim-full of possibilities. For an activist museum, especially one that has demonstrated through apprenticeship its desire to have palpable impact on people and communities, can Gweithdy prove, with time, to be an example of how museums can offer people real skills that can be applied outside of a museum? Could it become a place to create protest banners, to re-train, to fix your appliances? For anyone interested in museums’ ability to use their resources to improve people’s lives, Gweithdy may be one to watch.

Conclusion

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201304/012Being able to walk into historic homes, crossing the threshold and back into a historic Wales has always been possible at St Fagans. What has changed since its redevelopment is the ability of the past to talk to us, in the present, and impact our lives through the democratisation work conducted by the Museum. Seldom have I experienced such an opportunity to reflect on both past and present in a pertinent and important-seeming way as the interactive debates in Wales Is. Many working in museums will also appreciate the ability of Life Is not only to make past stories feel relevant to contemporary lives, but to represent all kinds of lives experienced now, and in the past.

National museums can seem lofty and abstract, providing symbols and traditions that are closed off and bear little relevance to your work, school, community or politics. Whilst St Fagans still needs to work out how its galleries’ new activist approach will have an impact on people’s experiences as citizens of Wales, this is a place that is beginning to feel like a national museum truly working with the nation it represents, finding ways of empowering collections to change our lives.