‘Contemplative wonder’: the potential for learning in museum open storage

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/252404

Abstract

Developing from the principle of democratising collections, there is an increasing call to turn museum open storage into places for visitors’ learning. Much of the existing literature has suggested that encountering huge collections without interpretation or guidance can be overwhelming for visitors (Dawes, 2016; Slater, 1995). However, an emerging counterargument suggests that open storage without curation empowers visitors to explore the area freely and enjoy unexpected encounters with objects within vast collections (Bond, 2018; Keene, 2005, Thiemeyer, 2017). Using a case study of the Open Store in the National Railway Museum (NRM), York, this paper examines the potential for embodied learning in open storage seen through the lens of contemplative wonder (Schinkel, 2017, 2020). It argues that contemplative wonder is an important learning tool with strong affective power and the ability to stimulate imagination. Using qualitative data gained from adult visitors through accompanied visits, personal mind maps and interviews, this article demonstrates that the distinctive characteristics of museum open storage can indeed evoke visitors’ contemplative wonder. The visit experience had strong affective power and stimulated visitors’ imaginations. The potential of contemplative wonder for learning is evident since it encouraged visitors to connect to their personal experiences, generate questions, and exhibit reasoning and expressing a view on world development. Interestingly, this study also found that in the setting of museum open storage, feelings of confusion and being overwhelmed were always found when visitors experienced contemplative wonder, leading to the conclusion that these two feelings are not necessarily hindrances to visitors’ learning as existing literature suggests.

Keywords

adults, affective power, contemplative wonder, imagination, museum learning, open storage, wonder

Introduction

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/In contrast to what visitors usually think of as a typical museum display space, museum open storage, with its distinguishing features of minimal labels, high concentration of objects and non-thematic categorisation, seems completely alien to visitors (Thistle, 1994). Contemplative wonder is a response to something we perceive as ‘strange’, ‘mysterious’ or ‘fundamentally beyond the limits of our understanding’ (Schinkel, 2020, pp 46–47). As such, museum open storage can be a place for visitors to experience contemplative wonder.

Scholars suggest that contemplative wonder can be an important learning tool because of its affective power and its ability to evoke imagination (Schinkel, 2020). Affective power and imagination have both been proven to have a positive link with learning in formal learning settings (Dean and Gilbert, 2022; Fleer, 2013; Gilbert, 2013; Gilbert and Beyers, 2017; Hadzigeorgiou, 2012; Stolberg, 2008). This research brings the concept of contemplative wonder from the formal learning setting to the museum setting. It argues that the concept brings a new perspective to exploring the potential of museum open storage for learning. Previous studies have suggested that the limiting role of curation can turn open storage into a place for visitors to explore and discover (Crenn, 2021; Keene, 2005; NMDC, 2003). Thistle (1994, p 207) describes this kind of discovery experience in open storage as ‘museological adventurism’. Wonder is believed to be evoked by the overwhelming and unmediated encounter with many objects, thereby supporting more imaginative, self-guided exploration, and active engagement than in curated collections (Bond, 2018). Others have argued that wonder cannot help visitors learn about objects (Lord, 2016), but rather having minimal interpretation of objects to inspire wonder may only bring frustration to visitors while failing to satisfy visitors’ desire for information (Lord, 2006). Open storage is also criticised as intimidating and confusing due to the overwhelming amount of objects and novelty of display (Dawes, 2016; Slater, 1995).

It is clear that there are mixed feelings about the potential for visitors’ learning in open storage and mixed attitudes towards the use of wonder. Moreover, there has been limited empirical research to support the arguments with very little published literature exploring the topic from the visitors’ perspective.[1] In addition, wonder has been ill-defined in existing museum literature. This lack of definition coupled with conflicting opinion suggests that this is a field for further research.

The research described here aims to bridge the knowledge gap by exploring two questions: What elements of open storage can evoke visitors’ contemplative wonder? And in what way do different contemplative wonder experiences create the potential for learning? Through accompanied visits, personal mind maps and interviews with adult visitors in the Open Store at the National Railway Museum the author explores the connection between contemplative wonder and visitors’ learning in museum open storage. While providing a relatively small case study, this research provides empirical backing for the incorporation of contemplative wonder practices by museums in the future, thus opening up even broader possibilities for learning.

The research context

Conventionally, the power of wonder has been valued because of its ability to stimulate inquiry and the search for answers. For example, Trotman (2014) stresses that an inquiring mind has to be evoked by wonder in order to learn – an initial ‘Wow!’ is needed which can then be transformed into the inquiring ‘How?’ and ‘What if?’ (p 24). This perception has tended to marginalise the affective element of wonder (Conijn et al, 2022; Hadzigeorgiou, 2014). Schinkel’s innovative idea on wonder, instead, emphasises its affective element, which is expressed in the term ‘contemplative wonder’.[2] Schinkel suggests that contemplative wonder is an important learning tool precisely because of its affective power and its ability to evoke imagination.

Affective power

Schinkel (2020) argues that the importance of contemplative wonder lies in the affective change it induces, comprising a mixture of puzzlement, interest, admiration, awe, surprise, fear and so on. Cognition and affect have been proven to be interdependent with each other (Kuo et al, 2024; Mottet, 2015), and affects are proven conducive to longer-term learning (Bodin and Pikunas, 1977). Sundberg and Anderson (2023) demonstrate that the sense of wonder expressed by students with the presence of emotions – including surprise and mystery – can be delineated into evolutionary concepts. Using a comparison with a control class with no attempt to foster wonder, Hadzigeorgiou’s study (2012) found that the participant group retained more ideas with a higher percentage of correct explanations.

Hadzigeorgiou’s study (2012) also showed that wonder with the presence of affective change encouraged students to question and comment – the participant group where wonder was encouraged handed in more journal entries with at least three times more questions and comments than the control group. Similarly, studying students from grades 3–5, Dean and Gilbert (2022) found that emotional wondering can stimulate students to question, hence engaging them with inquiry, in which state they develop procedures to test their questions.

Wonder also brings learners’ attitudinal changes to the subject matter. Stolberg (2008) proves that wonder-related events involving emotions can be translated into heuristic responses, through which teachers who distance themselves from science make their meaning of science actively. A similar result is obtained from two studies in which wonder is proven to help change participants’ negative perception of science and the particular science subject (Gilbert, 2013; Gilbert and Beyers, 2017) shows that wonder can trigger interest even in ‘science haters’ (p 22).

The studies above establish the positive link between wonder with an affective power and learning. However, the studies are all conducted in the formal learning setting, which is different from museum learning. Rather than having a primary focus on cognitive gain, affective, interpersonal and social learning also matter in museum learning.[3] Likewise, only linking wonder with cognitive gain is limiting, as wonder also engages us emotionally, aesthetically and existentially (Schinkel, 2017; Wolbert and Schinkel, 2021).

Imagination

Contemplative wonder reveals a world beyond one’s existing experience by ‘opening up the world’ to an individual (Schinkel, 2020, p 117), hence, sparking one’s imagination. The power of imagination does not only lie in fostering an individual’s understanding of the object that triggers wonder, as discussed by Hove (1996), but also enriches one’s grasp of broader subject matter, as shown by Fleer (2013), and Jankowska, Gajda and Karwowski (2019). Fleer’s study shows that children can successfully change the meaning of objects and are able to imagine new possibilities in roleplay. For example, by imagining the sand in front of them as porridge children connected their everyday experiences of hot porridge and cold porridge, and were thus able to further understand difficult concepts (i.e. convection or conduction).

For Schinkel, imagination can also enrich one’s understanding of the world by allowing visitors to make a connection from the actual object into the ‘deep past’ and ‘deep future’ (Schinkel, 2020, p 122). This view echoes many scholars who believe imagination enables an individual to go beyond the actual and see the possibilities (Egan, 1990; Vygotsky, 1991, 2004; Warnock, 1976). Through imagination, people can construct meanings that draw on various possibilities (Silverman; 1989; Vygotsky, 2004). This ability is crucial to thinking. It is facilitated by contemplative wonder which stimulates attitudinal change and opens up new possibilities to think critically and challenge our existing beliefs. This concurs with the advocacy of transformative learning put forward by Mezirow (2008).[4] Shank (2016) demonstrates that imagination being integrated into transformative education can provide learners with spaces to engage with possibilities and think divergently.

Wonder in open storage

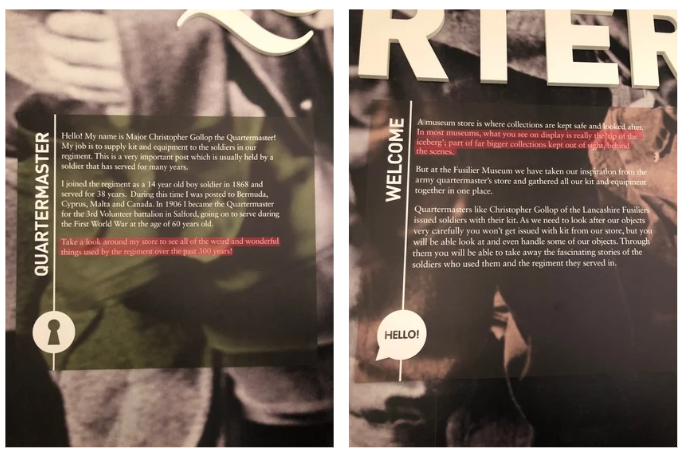

The development of open storage can in some ways be seen as reviving the approach of the Enlightenment museums with their display of large quantities of objects with little interpretation. Some scholars welcome this approach: Greenblatt (1991) expresses his regret about the transformation of museums in the nineteenth century from places of wonder to places of resonance – shifting the focus from objects’ materiality (i.e. aesthetic appearance) to interpretation. Likewise, Lord (2006) argues that a recent trend to use minimal interpretation and remove authoritative text helps to elicit visitors’ sense of wonder and allows visitors unmediated encounters with objects and to generate personal responses. These views suggest that a sense of wonder has always been seen as valuable and suggests that the mode of display in open storage may be conducive to it (Bond, 2018; Brusius and Singh, 2018; Caesar, 2007; Keene, 2005). When introducing open storage, museum professionals emphasise its distinctive characteristics: the exploration of the behind-the-scenes, the exploration of vast hidden treasures, and the privilege of entering the always-prohibited (Figures 1 and 2). These characteristics are all alien to what museum visitors now expect when visiting a museum gallery. Whether consciously or not, conceiving and describing open storage in this way can trigger visitors’ wonder by directing them to observe something that challenges their expectations and reveal the limits of their existing knowledge about museums themselves (Schinkel, 2020).

However frequent the deployment of wonder may seem in museum open storage, most existing literature does not attempt to define what wonder is, but generally relates it to discovery, curiosity and surprise regardless of the subtle differences among these responses.[5] Limited understanding and exploration of the full potential of wonder in the museum setting contributes to the denial of its power in facilitating visitors’ learning. Lord (2016), for example, rejects the use of wonder in museums, drawing on Descartes’ view that wonder can be harmful if ‘one wonders too much’ and ‘one is astonished by things that are not worth dwelling on’ (Lord, 2016, p 102).

These arguments fail to recognise the subjectivity of wonder – the object that catches one’s attention is the one that an individual personally considers important and meaningful (Schinkel, 2020; Tobia, 2015). In this sense, criticisms of wonder fail to use the constructivist approach to learning which has an emphasis on the agency of the learner. Lord does not acknowledge the active participation of the learner, through which knowledge is constructed, not merely absorbed. Additionally, Lord neglects other aspects of museum learning but merely focuses on intellectual understanding.

The view that excessive wonder is hindering visitors’ learning is not novel in the museum studies literature when talking about open storage. Due to the minimal interpretation and vast amounts of objects on display, some scholars suggest that wonder may become overwhelming, and elicit feelings of confusion, leading to frustration and obstructing learning, as discussed by Caesar (2007), Dawes (2016) and Slater (1995). However, the author’s analysis refutes the suggestion that feelings of overwhelm and confusion cause wonder to become ineffective. When we consider what Hadzigeorgiou (2016), Opdal (2001) and Schinkel (2020) suggest wonder is, experiencing it may clearly not be pleasant at all. Due to the existence of the unexpected and surprises that are beyond one’s imagination, perplexity and dislocation inevitably occur. These emotions are two of the many possible emotional components of wonder. Yet, confusion and frustration are found to be closely linked with deeper engagement in the museum setting (Rappolt-Schilchtmann et al, 2017) and can be harnessed in exhibitions to deepen visitors’ learning and engagement (May et al, 2022). The following case study explores these more nuanced aspects of contemplative wonder and its role in promoting learning in museum stores.

Method: case study

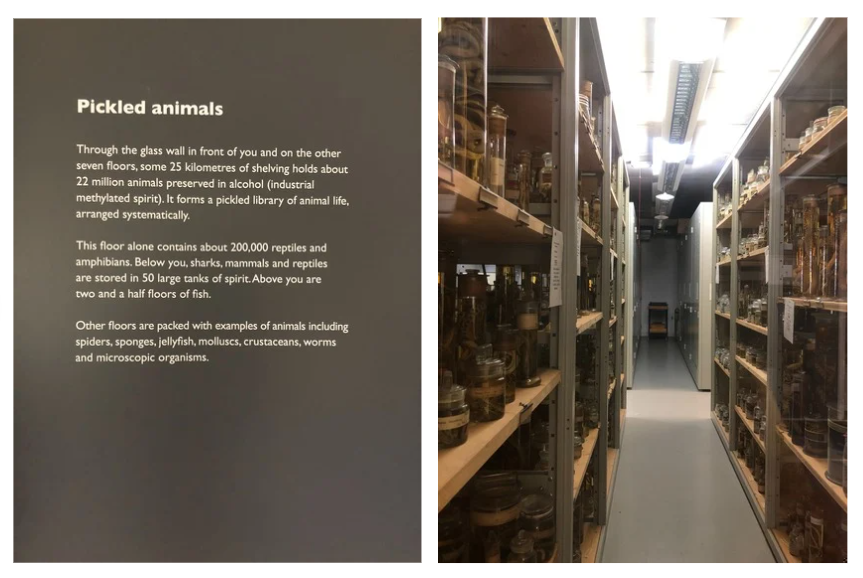

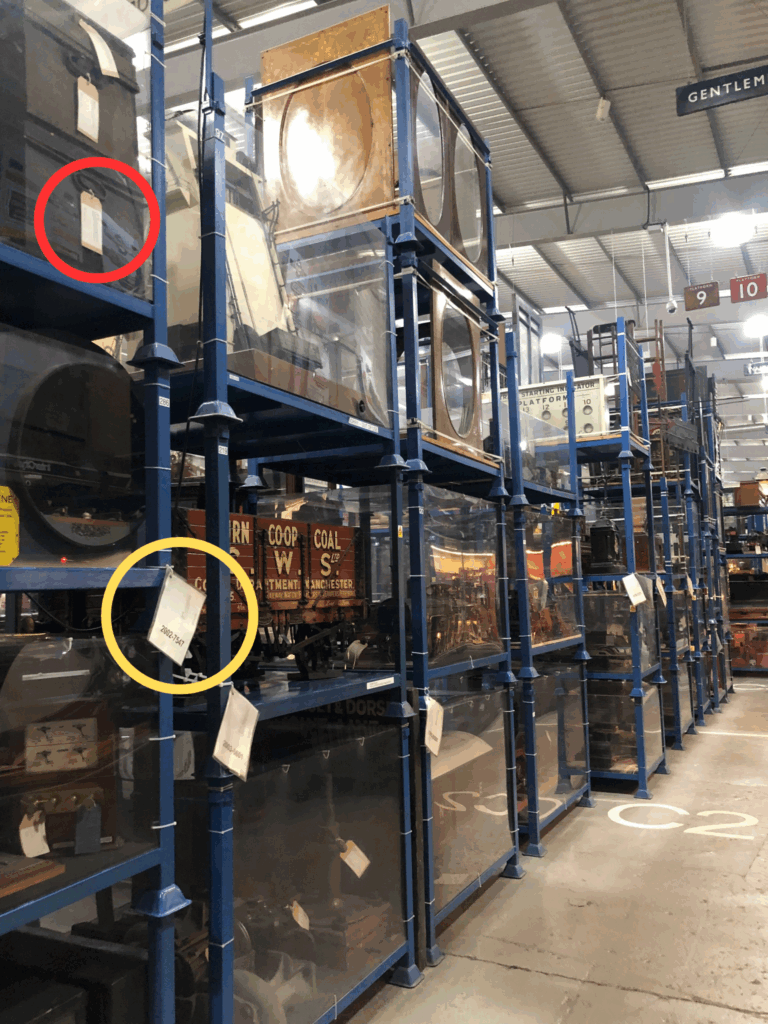

Established in 1999, the Open Store at the National Railway Museum covers 2,400 square metres, holds over 3,000 objects and has been designed with minimal text interpretation (Wright, undated). The Open Store is a typical open storage facility – having minimal labels, high concentration of objects and non-thematic categorisation (Thistle, 1994). Visitors can have full and unaccompanied access to the whole store.

The Open Store functions as a working object store for the Museum as well as a public space. Filling a high-ceilinged warehouse-like space it holds a huge variety of railway-related objects from teacups to large pieces of signalling equipment of varying size, material and sturdiness. Smaller, more fragile items are stored in glass cases, large items are free-standing on the floor or on industrial shelving, or in the case of the large collections of railway signs, attached to the walls (Figure 3–5).

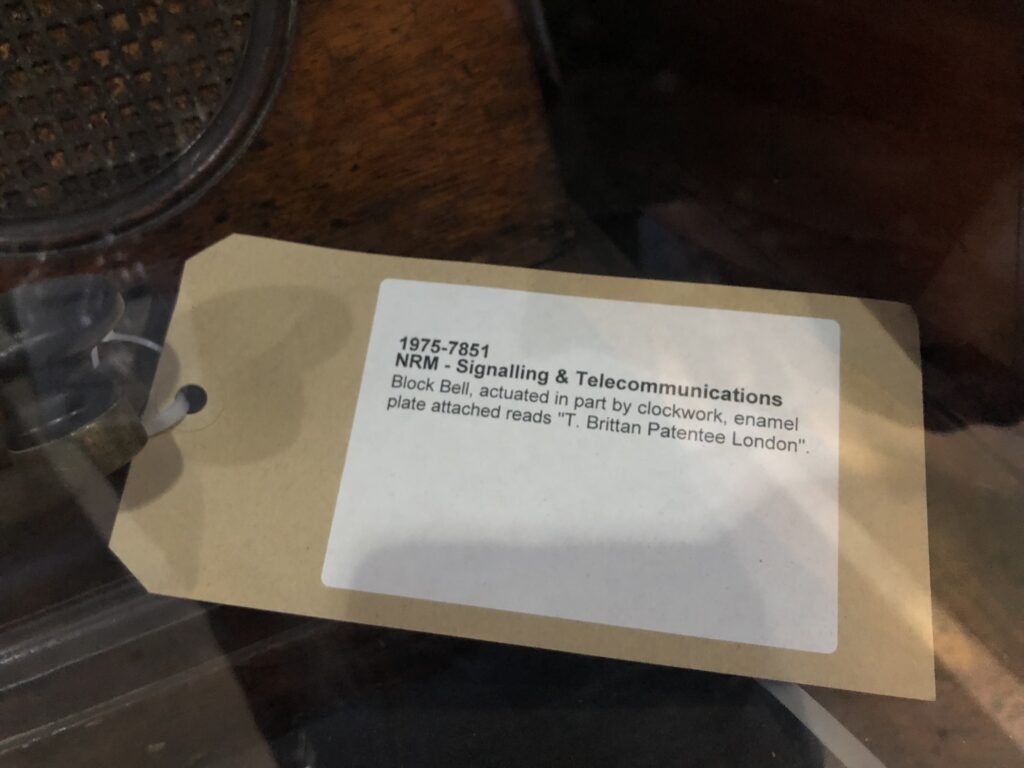

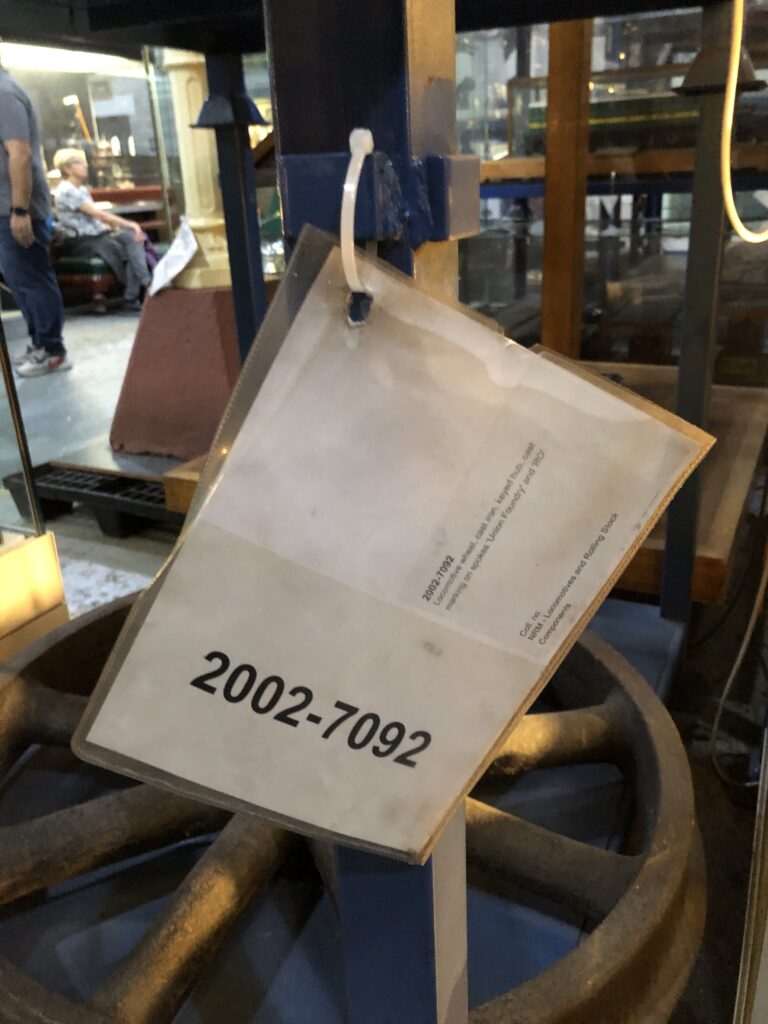

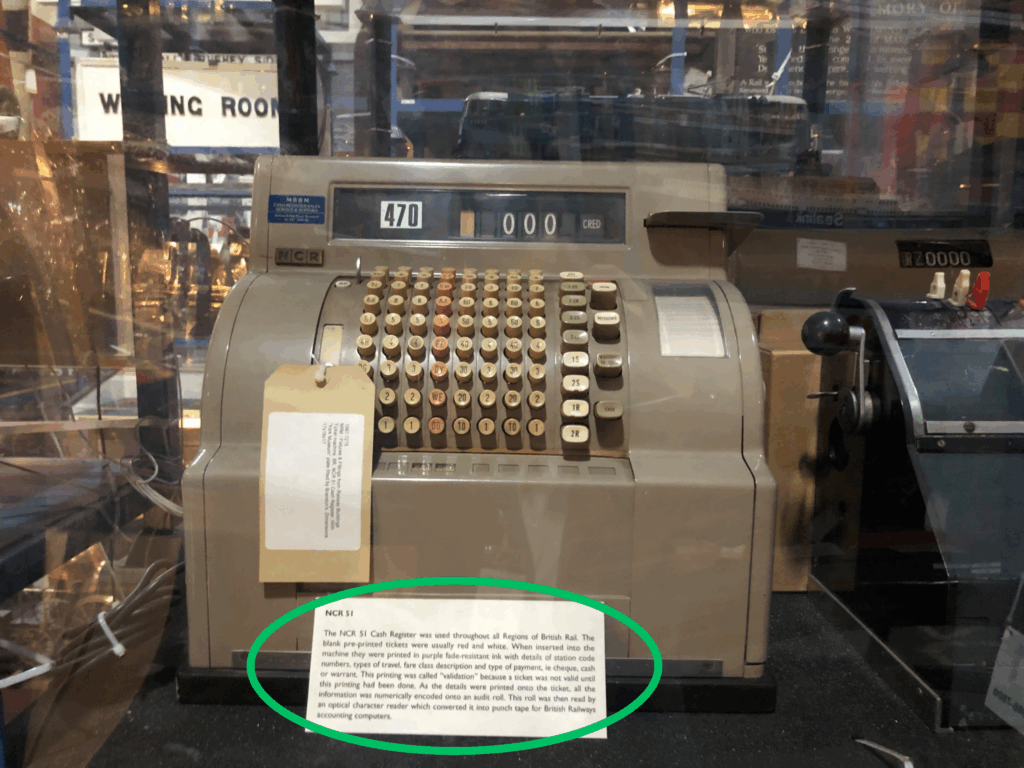

Two main types of text intervention are used in the store: a ‘luggage tag’ type of label; and a laminated label (Figures 6–8). Both types of label are for Museum use rather than intended as interpretation for the visitor. They are very minimal, showing the inventory number of the object prominently and containing other technical information about the object or its acquisition.

A third form of text in the Open Store is shown in Figure 9 (below). This kind of label is similar to the object labels more commonly found in museum displays and is clearly intended as interpretative text for visitors. However, this kind of text can only be found for a small number of objects in the Store.

Data collection and analysis

The research, consisting of a pilot and a main study, was conducted on two consecutive days – one whole Friday and Saturday in July 2023. Adult visitors were approached when they were entering the Open Store. 14 out of 25 visitors who were approached participated in the research (Table 1).

| Number of visitors approached: | Pilot study: | 2 |

| Main study: | 23 | |

| Total: | 25 | |

| Number of visitors accepted: | Pilot study | 2 |

| Main study | *14 | |

| Total: | 16 | |

| Total acceptance rate: | 64% | |

*Two visitors withdrew from the research after reading the information sheet

Table 1: Number of visitors approached and accepted for participation in the research

The author used an accompanied visit design based on the method used by Eilean Hooper-Greenhill and Theano Moussouri (RCMG, 2001a; 2001b). Participants were asked to voice their thoughts and feelings about both the collections and the space to the author as the visit progressed. Participants could interact with the Open Store however they liked. During the accompanied visits, the author took field notes by observing participants’ verbal and non-verbal behaviours. The data were then used to compare and map with the characteristics of contemplative wonder listed by Schinkel (2020).

Accompanied visits are a kind of participant observation in which the presence of a researcher will inevitably influence participants’ level of reactivity (Punch, 2005, pp 183–184). However, the author limited their role to observation and prompting participants’ questions, rather than directing participants’ visit. Prompts for explanations have been found to be a practical method to address the difficulties of eliciting participants’ otherwise unspoken thoughts (RCMG, 2001a; 2001b). The participants’ own explanations also avoided misinterpretations made by the author and gave accounts of their behaviours during their visit (Corbin and Strauss, 2015).

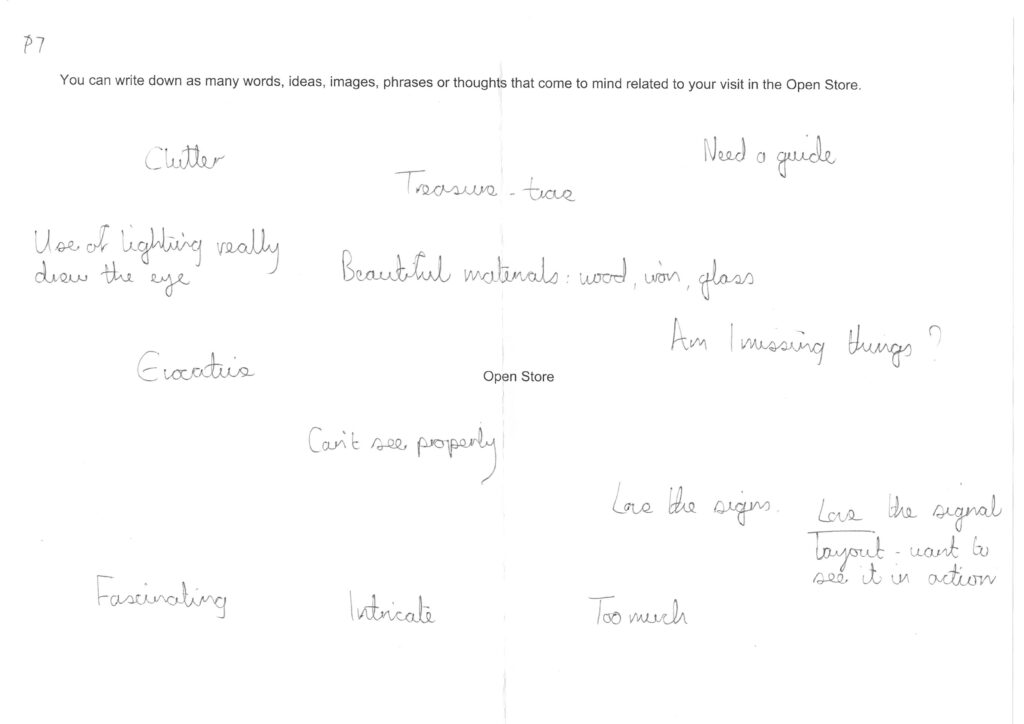

After the accompanied visit, participants were asked to draw a mind map describing their experience of the visit – a mind map is a diagram that visually organises words, ideas or concepts branching out from a central word or concept (Wheeldon, 2011). Mind maps can help participants chart their experience in depth and detail (Wheeldon and Ahlberg, 2019). They prioritise qualitative individual narrative, helping address research biases (Punch, 2005; Wheeldon and Ahlberg, 2019). The mind maps created by participants were used as an entry point for the next activity: a semi-structured interview. The author asked participants follow-up questions for elaboration on what they had written in the mind map. The interviews were not a direct data excavation process; instead, the author invited participants to recall their visit to the Open Store (Silverman, 2021; Yin, 2018). By actively combining their recollections with what they had written in the mind map, participants could ‘construct’ their narrative with in-depth information about their wonder experiences (Yin, 2018, p 62). Analysis of these data was used to explore any links between participants’ contemplative wonder experiences and learning.

The methodology was not changed after the pilot study as the results confirmed the feasibility and quality of the research. The accompanied visits and interviews were audio-recorded and fully transcribed. The data was then subjected to thematic analysis via Nvivo, the standard software programme for qualitative mixed-methods research.

Participant profile

A total of 14 participants – ten individuals and two groups each consisting of two participants – took part in this study. Six participants were female and eight were male. Eight participants were first-time visitors. Participants were mostly British, aged over 56, educated to university degree level, and had never been to any open storage facility in other museums before. No participant had a job directly related to railways; all were interested in railways or other transportation with different levels of interest and knowledge.

It is difficult to prove whether the participants involved are representative of the visitors of the Open Store due to the absence of the latest visitor profile from the Museum data. However, according to a 2003 report on the Open Store (Questions Answered, 2003), the ratios of female visitors and first-time visitors in my research were much higher, while still being predominantly British. The report did not have any data related to other socio-cultural demographic information that were collected in this study.

What evokes contemplative wonder?

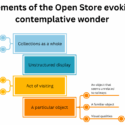

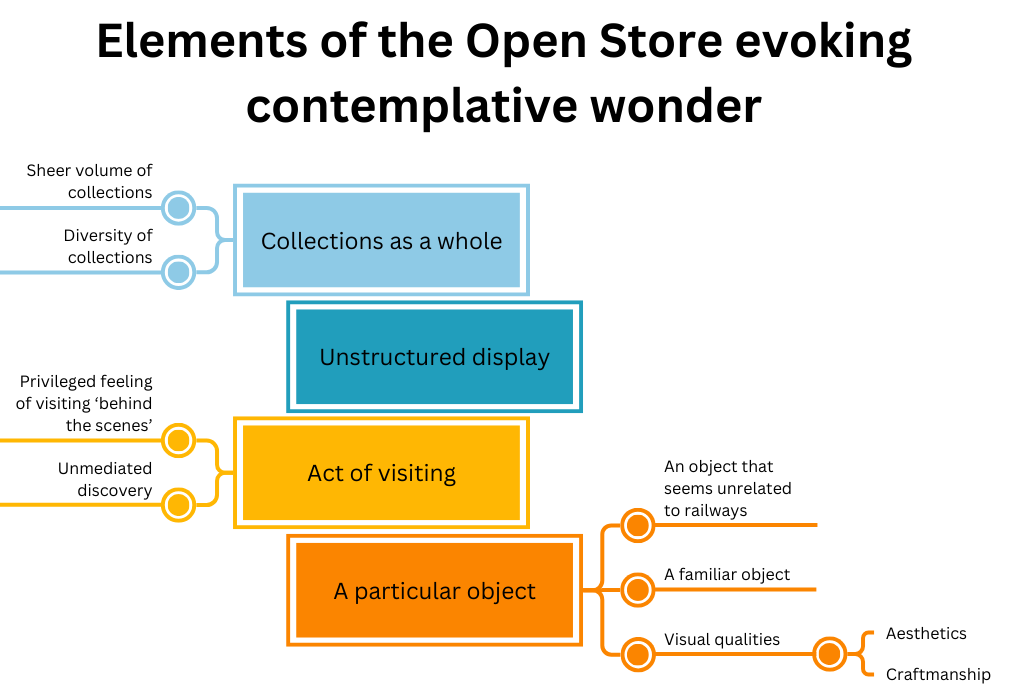

Although not attempting to pin down wonder into one singular type of experience, Schinkel pulled together a list of characteristic elements of wonder. Summarising that list, wonder is triggered by a tangible or intangible object which arrests one’s attention with the presence of a mixture of feelings, including but not limited to, surprise, puzzlement, perplexity (Schinkel, 2020). In the case of contemplative wonder, that object is something that the receiver perceives as ‘strange, deeply other or mysterious, fundamentally beyond the limits of our understanding’ (p 47). Situating this concept into the context of this, the study found that the sense of contemplative wonder was evoked by four key elements of the Open Store (Figure 11) – participants’ attention was captured by these four elements:

- the sheer amount and diversity of the collections

- the unstructured display

- the privileged feeling of visiting behind the scenes and the unmediated discovery

- a connection to a particular object.

These elicited the visitors’ emotions and stirred up their imaginations, suggesting that their experience corroborated Schinkel’s definition of contemplative wonder.

Collections as a whole

All 14 participants wondered at the collections: the sheer volume (13 participants) and the diversity (9 participants) of the collections. Comments showed that contemplative wonder was elicited by these two elements via reactions of either surprise and admiration or being overwhelmed as participants had never seen so many different collections in any museum.

Sheer volume:

When I saw people coming in here [the Open Store], by curiosity, I got here. I was really surprised. So many things here. (P6)

It’s a bit overwhelming and I’m not sure what I’ll look at… It’s almost like there’s too much to look at. (P1)

Diversity of collections:

It’s not especially something as large as a train. This has all the furniture and equipment and china is even here. It’s very nice to see this model [pointing to the signalling school]. This is great. (P1)

Further analysis revealed that participants’ comments on the collections as a whole were far more complex than mere surprise or confusion, pleasant or unpleasant. Instead, when participants were wondering at the many collections in front of them, they experienced a myriad of affective changes, and a more complicated process of experiencing contemplative wonder which went through changes – from an initial response of ‘disorientation’ or ‘dislocation’ to an ‘attunement towards mystery’ (Schinkel, 2020, pp 22, 47). Three participants described this dislocated kind of contemplative wonder amidst the volume and diversity of the collections.

It may sound stupid but it’s just coming to mind. You know, when you go into a nightclub or discotheque and all that’s going on and you don’t know what’s happening and you just have to get used to it and then start looking around…it’s…slightly like a drug experience. (P2)

The above quote exemplifies the experience of contemplative wonder: upon entering the Open Store, the visitor first experienced disorientation of not knowing what was going on, and a sense of being overwhelmed. The participant then took some time to settle in, waiting for the disorientation and sense of being overwhelmed to wear off so that he could begin to explore the objects.

Unstructured display

The unstructured format of the Open Store was beyond the participants’ usual experience of museum displays as thematic and curated. Objects were stacked rather than arranged thematically. This lack of perceivable organisation of objects made participants describe the Open Store variously as a ‘warehouse’, ‘B&Q’, ‘antique shop’, ‘jumble’, ‘storehouse’, ‘treasure trove’ or ‘charity shop’. Twelve participants wondered at the unfamiliarity of this method while exhibiting different emotional responses. The emotions evoked with wonder were vastly different among participants, in particular relating to whether they were first time or returning visitors (which might relate to the degree of familiarity with the storage type of space). Returning visitors found joy and interest in the Open Store due to its non-conformity. They were relatively comfortable with this experience. For example, Participant 2 enjoyed the feeling of wondering how objects could spark his imagination:

It’s not in any logical order so it’s just interesting. It’s just like a dream, if you will, how your dream can go from one thing to another with no real connection.

As a first-time visitor, Participant 9 also found joy in being in unstructured storage since she enjoyed going to antique shops, with which she compared the Open Store:

It’s looking back on the old things that you don’t see anymore, like the leaded glass. Like this. I like the lanterns; I like the brass; I like all these and I love the way it’s stacked. This gives me joy.

On the other hand, five participants who were not familiar with the method of display experienced unpleasant wonder with the confusion and dislocation also mentioned by Schinkel (2020). Participant 7, who explicitly mentioned being ‘anxious’, summed up this sense of confusion when she repeatedly asked, ‘Am I missing anything?’ during her accompanied visit and in her mind map. She was astonished at how the objects were placed in such an unstructured display and described the Open Store as a ‘treasure trove’. However, the same wonder also made her continue by commenting the display was overwhelming, as she was unsure of how she was ‘supposed to interact with it [the display]’.

The act of visiting

The privileged feeling of visiting ‘behind the scenes’ was another trigger for participants’ contemplative wonder. Six participants were aware that museums have objects that are not on public display but which are instead placed in storage areas. Entering the Open Store with this knowledge gave participants a sense of privilege and aroused their wonder in thinking about what special objects could be seen in the space that was supposed to be off-limits for museum visitors. Participant 2 particularly enjoyed wandering in the Open Store, which he described as ‘the best part of this Museum’, and found it interesting to see things other than the big engines in the main gallery space:

I find this the most interesting that all the stuff that is not on display. There is so much behind-the-scenes stuff. It is really interesting…it’s just curiosity: what are you going to see next?

He later added:

I know what to expect there [the main gallery space] and I don’t know so much what to expect here [the Open Store].

The act of wandering in the Open Store was felt to be a journey of discovery for eight participants. Consistent with the literature (Bond, 2018), participants were free to explore the space without a designated route, due to the absence of signs and guides. Participants stopped only at things that caught their attention, as the two comments below demonstrate. Their exploration was broadly similar to Schinkel’s statement that people who experience contemplative wonder ‘wait for the object to approach’, rather than actively seeking out a particular item (Schinkel, 2020, p 42).

Things catch your eyes. But you don’t know what’s gonna be at the particular time. (2)

Really a lot to see, not clear where to go to now. Or just like I would probably just wanna pass by and then like whatever catches my interest, probably stop and think. [Right at the next moment, P3 continued.] OK, here now I see the models. Very big models as well. (P3)

When referring to the act of discovery, all eight participants mentioned it along with the sheer volume of the collections, the diversity of the collections or the unstructured display. As we read the above quote from Participant 3, we see that contemplative wonder was triggered when she discovered a particular object amid the vast collections displayed in an unstructured manner. This finding supports the claim that the immensity of collections can enhance the feeling of adventure (Bond, 2018) and serendipity (Conn, 2010) and accords with findings reported by Keene (2005) that clearly support the relationship between unstructured display and the feeling of adventure.

Is there potential for learning in the Open Store experiences?

Schinkel (2020) attributes the importance of contemplative wonder in learning to its affective power and ability to activate the imagination. The findings of this research support Schinkel by proving the presence of both components of contemplative wonder: emotional impact and inspiration. Rather than in a conventional sense of cognitive or intellectual learning, the contemplative wonder evoked by the Open Store demonstrated its link with learning by playing four roles: engaging participants by connecting their personal experiences; generating a source for questions; stimulating the use of reasoning; and evoking a view on world development. All these responses suggest the potential value of the Open Store for visitors’ learning.

Engaging participants by connecting their personal experiences

When experiencing contemplative wonder, participants emotionally engaged with the object or subject matter by connecting it to their lived experiences. Rummaging through objects in the Open Store triggered participants’ contemplative wonder through affective change, be it surprise, astonishment, confusion or a mixture of these. For example, 13 out of 14 participants employed their imagination to take them beyond the actual artefact and recall their personal experience, which enabled them to construct their own meanings related to the object. This research reflects Stolberg’s findings (2008) that wonder-related moments can help participants actively construct their own meaning of science.

Four participants recalled their trainspotting experience as a child or teenager when they spotted a particular train model or saw the collections en masse. The mural showing all the stops on the line from Waterloo down to Bournemouth reminded Participant 7 of the places where she used to go on holiday, the places she used to live and the places she used to visit her grandparents. Participant 4 was impressed when he first spotted the sign of the longest station name ‘Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantysiliogogogoch’ in the Open Store. This reminded him of somebody giving him a platform ticket with this name on it when he, as a child, went to visit his relatives in North Wales.

Probably due to the fact every participant was interested in railways, this research did not find any evidence of people engaging with the subject matter with an attitudinal change from negative to positive, which are suggested by Gilbert (2013), Gilbert and Beyers (2017), and Hadzigeorgiou (2012). However, this research demonstrated participants’ strong connection with the collections; it echoes Dudley’s view (2010) that museum visitors can be emotionally engaged with an object alone. Even though further studies are needed, how participants engaged with the collections by connecting to their personal experience opens the possibility that the absence of interpretation allows participants’ unmediated responses to an object (Dudley, 2010, 2012).

Generating a source for questions

Asking questions when experiencing contemplative wonder is a way for people to engage with the subject matter and a prerequisite of reasoning (Hadzigeorgiou, 2012; Schinkel, 2020). My research accords with this idea by recording that ten participants raised questions during their visit. The ones who felt confused during their visit tended to ask questions more often. Nine participants raised questions about objects, and especially those objects that seemed to be unrelated to railways, as the quotation below demonstrates. This finding confirms the power of unfamiliar and unexpected juxtaposition of familiar objects in museums in fuelling people’s imagination and questioning (Bond, 2018; Keene, 2005).

It looks like a gravestone, and I’m intrigued by that. Why is there a gravestone for the South Devon Railway? And why did it get the names of the directors in that really grim, sombre way? (P7)

Two participants questioned the display mechanism of the Open Store. Questioning the display mechanism may also demonstrate the strength of open storage in raising awareness of itself, instead of just the collections it holds. Although more rigorous studies are needed, this finding raises the possibility that museum open storage, by allowing visitors to challenge the museum’s representation practises, turns itself from a space or container into the focal subject matter of exploration (Lord, 2005, 2016; Thiemeyer, 2017).

Stimulating the use of reasoning

People experience contemplative wonder when they perceive that what they experience is beyond their current understanding. To fill the gap in their knowledge, people try to make sense of what they are encountering through their imagination (Schinkel, 2020), in which they connect their prior knowledge to what they have newly encountered (Vygotsky, 2004). This was also found in the Open Store – 13 participants tried to respond to their wonder with logical reasoning based on their observation and their prior knowledge. Eleven participants applied reasoning to try to make sense of the function of an object, whereas two did it to guess why a particular object was collected:

This is an interesting scale. I guess these locomotive models are sort of two feet long and four inches wide, and that is good for presenting detail… I suspect these are engineering models built to show – they do this with ships built – to show the board of directors what they are about to authorise being built. So, these probably are unique because they would have been built by the company intending to build the real thing, to present to the Board of Directors for approval to go forward. And there won’t be any other, so these will be historically valuable. (P12)

The above quote is a good example to illustrate the processing of reasoning. We can see that Participant 12 made sense of the object’s original function by roughly gauging the object’s scale (observation) and by making reference to ships (prior knowledge). From this, he concluded the uniqueness of the model and suggested that the Museum probably kept the model due to its historical value.

This use of reasoning corroborates the study of Dean and Gilbert (2022) who find that their participants develop procedures to resolve their questions which are evoked by wonder. Yet, my findings differ in their emphasis on the various ways participants used to resolve their queries. In Dean and Gilbert’s study the resolution procedure was translated into physical actions with the scaffolding of teachers. In my research, the procedure was unmediated and demonstrated reasoning, although the reasoning did not necessarily lead visitors to the correct answer. However, the presence of reasoning engaged visitors with the subject matter and helped them to construct their own meaning.

As mentioned, reasoning is based on one’s prior knowledge. This research found that those who had a higher knowledge level of railways tended to reason more often; nonetheless, one person who had a relatively lower knowledge level and constantly felt confused during the visit also tried reasoning. Participant 3, who lamented that she got nothing from the Open Store, still applied reasoning when she experienced wonder upon encountering the stained-glass door by which she was puzzled:

Probably it is kind of an official building. With this crossing the lines here, something from York maybe.

This presents a striking result that reasoning can still occur amidst confusion, which in turn suggests that confusion brought by wonder should not be seen necessarily as a hindrance to learning as has been stated in existing museum literature (Caesar, 2007; Dawes, 2016; Lord, 2016; Slater, 1995). What is more interesting is that reasoning most often happened upon the absence of explanatory resources. Even though nine participants urged for more information on the labels to improve their understanding of the objects, this research found that reasoning always took place after participants failed to find answers from labels. This finding provides the empirical backing for Dudley (2010, 2012) who believed that minimally interpreted exhibits could encourage both imaginative and reasoned responses.

Evoking a view on world development

Eight participants wondered beyond the object or the collections per se to world development through imagination, which supports other research concerning the power of imagination in helping one to go beyond the actual object (Egan, 1990; Vygotsky, 1991, 2004; Warnock, 1976) and enriching one’s understanding of the world, rather than merely focusing upon the object that triggers wonder (Hove, 1996). The collections en masse made seven participants wonder about technological development, usually, with an emotional response of astonishment and awe. This finding resonates with Dawes’ study (2016) in which participants attribute the educational value of open storage to the sheer amount of collections. The sheer amount of collections on display exposes them to a culture different from theirs and from the rest of the world.

For a sense of engineering pride [P8 later changed the wording to awe] about so many stuff that is in there and know about the great things that people have done, the technology that we’ve done. (P8)

Change in technology – from steam power to electric. (P14)

Era gone. Yeah, it’s progress. (P4)

Four participants wondered about the differences between the past and present train journeys when they saw the silverware which was assumed to be used on trains in the past, lamenting the fast pace of today’s world. By connecting the present to the ‘past’ and ‘future’ (Schinkel, 2020, p 122), Participant 12 even associated the silverware to energy consumption, wondering about the uneven distribution of resources in today’s world. Yun (2018) contributes this kind of reflection to the result of the availability of full access to objects which are displayed in a non-thematic way. This presentation way of objects rejects the reduction of objects to categories but allows them to be seen as a whole, reminding visitors of their participation in ereignis. In other words, the contemplative wonder triggered in Open Storage engaged participants existentially, in which participants were able to recognise the current limits of their understanding of the world, challenge their previous perceptions and have an openness to the world (Schinkel, 2020; Yun, 2018).

Conclusion

Analysis of data collected from 14 adult visitors – through their accompanied visits to National Railway Museum Open Store, their personal mind maps, and informal interviews conducted by the author – has revealed three key research findings. Firstly, that open storage can evoke participants’ contemplative wonder, which is a response to something we perceive as ‘strange’, ‘mysterious’ or ‘fundamentally beyond the limits of our understanding’ (Schinkel, 2020, pp 46–47). The sense of contemplative wonder is aroused by the distinctive characteristics of museum open storage, which are unfamiliar to most participants, including the sheer number of objects, the diversity of collections, the unstructured display, the privileged feeling of visiting ‘behind the scenes’ and the unmediated discoveries. These findings indicate that participants experienced contemplative wonder when they encountered objects or collections beyond their current understanding or familiarity, and perceived them as confusing, amazing, overwhelming or intriguing; such perceptions map onto Schinkel’s theoretical framework.

Secondly, visiting the Open Store can initiate contemplative wonder experiences that create potential for learning due to the affective power wonder generates and the imagination it stimulates. The affective power and imagination play a very prominent role in engaging participants with objects, subject matter and even museum representation practices. In response to the wonder triggered in the Open Store, participants connected what they saw to their personal experiences, questioned, reasoned and expressed a view on world development. These four responses to their own wonder experience indicate the potential for learning in the Open Store. A more controlled study will be needed to examine the link between wonder and learning in detail; for example, how these wonder experiences affect a particular aspect of an individual’s understanding, be it conceptual, attitudinal or emotional.

Thirdly, by identifying a spectrum of emotions in the contemplative wonder experiences, the research shows that confusion and being overwhelmed are not necessarily hindrances to visitors’ learning. This research supports the idea that experiencing wonder and in particular contemplative wonder is not always pleasant (Hadzigeorgiou, 2016; Odpal, 2001; Schinkel, 2020). Yet however uncomfortable they may feel, participants who are confused and overwhelmed still deeply engage with objects and the subject matter.

The presence of negative emotions in wonder and as well as its clear positive relationship with the potential for learning provides new insights into the museum discipline. This research disproves the claim that visitors who are confused and overwhelmed are not able to learn from museum open storage. The potential for learning from museum open storage should not be denied simply because of the presence of negative emotions. Contemplative wonder can act as an entry point of learning regardless of whether or not knowledge is gained from the space or from beyond it. Without interpretation and exhibition narrative, visitors wonder about objects necessarily through their own explorations. In this perspective, museum open storage acts as a place for imagining through emotional and unmediated encounters.

Due to the self-directed nature of museum learning, visitors’ sense of wonder and learning are not as structurally mediated as suggested in the literature which focuses on the formal learning setting. For museums that want to develop open storage facilities, the next challenge will be how to sustain the sense of wonder and how to make the best use of wonder as a hook to maximise the learning effects on visitors. As shown in my research and other literature (Bond, 2018; Orcutt, 2011; Slater; 1995), a dilemma always lies in whether to provide interpretation which can satisfy visitors’ knowledge thirst but, at the same time, displace the role of wonder in prompting participants to think and make sense of what they saw through reasoning. My research gives credence to the supporters of minimal interpretation in museum open storage, but the dilemma shown in this research is still not able to answer the question troubling many professionals, including Caesar (2007): ‘does interpretation create added value from a public perspective, or is it sufficient for them to be able to simply view the collection’ (2007, p 17). More studies on the value and extent of interpretation in museum open storage are needed.

Further research

To design museum open storage in ways that fully achieve its potential, it would be valuable to identify further differences between the typical museum display space and open storage by comparing how people interact with the objects and space in the two areas. Moreover, open storage facilities vary in terms of level of accessibility and formats. My research only focuses on one type of open storage facility; further studies on other types of storage space are needed. Children’s responses to wonder are different from adults (Opdal, 2001; Schinkel, 2020), and wonder is very important to children at early ages (Edeiken, 1992; Piersol, 2014; Thomas, 2016). Children’s contemplative wonder in different formats of open storage could, therefore, be a valuable contribution to child-centred museological approaches.

Acknowledgments

The original paper was submitted as a dissertation paper for the degree of MA in Museum Studies of University College London in 2023.