Collaborative working with challenging histories: the Railway Work, Life & Death project

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/252405

Abstract

This paper reflects upon notions of value for research collaborations with differing stakeholder agendas and suggests modes of working that could be useful to other academic/Galleries, Libraries, Archives, Museum (GLAM) collaborations. It focuses on the Railway Work, Life & Death project, a collaboration between the National Railway Museum, University of Portsmouth and a number of other institutions. It demonstrates the benefits that meaningful, long-term collaboration can provide to those involved, and to wider stakeholder communities. It also considers some of the challenges of working with difficult pasts – in this case, accidents which killed and injured many tens of thousands of railway workers, and which run counter to popular perceptions of a ‘golden age’ of rail travel in Britain and Ireland. These tensions are noted and related to 2025’s Railway 200 celebration as both an opportunity and a challenge in terms of telling more diverse stories about the past.

Introduction

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/According to Keri Facer and Kate Pahl (2017), it can be hard to define why collaborative working is so important. It can be challenging to articulate the value and impact of qualitative outcomes this type of work can bring, especially when parameters for working are flexible and responsive to partners’ needs and requirements. For projects with no deadline and no funding bodies to report to, taking time to consider value and impact of joint working can slip down the To-Do list and yet it is important. The act of recording and reflecting upon a project is not only motivating for all involved – a ‘look how far we have come’ moment – it is vital in orientating and re-focusing the project’s direction (Foster, 2023). In writing this paper – a collaborative project in its own right – reflection, celebration and review are considered, and conclusions proffered as ways of working in other projects and collaborations between academia and museums.

We want to advocate for the importance of collaborative working, offering one example as a case study – the Railway Work, Life & Death project, a collaboration between the National Railway Museum, University of Portsmouth and others. We argue that putting people at the heart of the collaboration is incredibly powerful – both by focusing attention on people in the past, and by considering the benefits to people involved in the project, a great many of whom were and are volunteers.

In what follows, we start by introducing the Railway Work, Life & Death project, the collaboration at the heart of the article. Via a case study, we demonstrate the power that personal stories can hold, in terms of understanding the past and museum visitor engagement with collection objects. We go on to consider a range of perspectives, institutional and individual, on the values and challenges of collaborative practice. Finally, we explore some of the ways the project has reached beyond museums and academia and contributed to the work of different stakeholder groups. Taken together, the article shows the power of collaboration in action in museums and higher education environments and advocates for the importance of time to develop and undertake these collaborative projects.

The Railway Work, Life & Death project

To provide context, the Railway Work, Life & Death (RWLD) project started in 2016, as a collaboration between the National Railway Museum and the University of Portsmouth. Since that time, it has shifted in focus, branched out and involved many more people and organisations than was first envisaged. Its genesis was to provide a dataset of railway workers affected by industrial accident. Putting the people back into the railway story was crucial to the project ethos. Railway history, in both popular and academic discourse, has often been focused on telling the technologically driven story of ‘big things’ – particularly the engines. The social history of the railway, in particular the workforce and related material culture, has often been overlooked: Frank McKenna’s 1980 book on railway workers is still the definitive title on the subject in the UK, despite being over 45 years old.[1] Colin Divall and Andrew Scott (2001) stressed the importance of social history to the general visitor to transport museums and that a more human recentring is integral to this type of museum’s audience sustainability. One of the barriers to this is the difficulty – real or perceived – in being able to study and analyse workers and their histories. One place known to offer opportunities is a body of investigations into workplace accidents before 1939. These records shine a light on the people involved, giving working-class people prominence, as well as providing insight into occupational practices and labour relations. For Esbester and Baker, turning these records into a form that could be used was an avenue worth exploring.

In its initial conceptualisation, transcribing these records and making them accessible digitally would serve two key audiences: family historians, including visitors to the NRM’s library and archive (Search Engine) who were enquiring about railway ancestors and the circumstances surrounding an accident, and secondly, as a useful resource for academic historians, giving them access to a large body of data that would otherwise be impossible for an individual researcher to produce.

The preliminary source of information was the official Board of Trade staff accident reports. But the physicality of these volumes – their large and heavy format and unindexed worker information – made finding a family member or other information impossible for all but the most intrepid. Esbester and Baker hoped bringing together worker names and accident contexts from these accident reports into spreadsheet form would be an achievable goal for an unfunded project. Both parties brought complementary skills to bear. Esbester, as the subject specialist, was able to see the academic worth of this information and the synergies bringing the names together in this way could bring. Baker brought user insight and the knowledge of how to undertake this work, having just completed a novel volunteer project producing an online subject catalogue using the card catalogue of railway historian Alan Jackson. The volunteers involved in this working-from-home project, the first of its kind within the Science Museum Group, had completed this transcribing work and wanted to work on similar projects. Tim Ingold’s notion of ‘enskilment’,[2] where social skills are developed through collaboration was in evidence here and the volunteers’ newly-acquired ability to decipher and synthesise data made them ideal volunteers for the RWLD project. A core team then moved across from this original project to deciphering railway accident records. And so, after a period of project design, ethical opinion (including consideration of the challenges of handling potentially sensitive or distressing information) and institutional approval, the collaborative work began. In due course, the completion of all the worker names and accidents from the Board of Trade were recorded in a searchable and publicly accessible dataset from the RWLD website.

As a result of being able to see a tangible end-product and resulting potentials, it was agreed to continue the project, reaching out to new collaborators with similar goals and collections. RWLD now works with the Modern Records Centre, home to railway trades union records, and The National Archives of the UK, where employee records for English and Welsh railway companies are housed. It has also developed links with the RMT Union, Network Rail, Transport for Wales and other connected organisations within the modern rail industry. The situation in 2025 is that the database has been downloaded 20,000 times by users from 105 different countries. It is a resource that has been significantly used, but what conclusions of value might we draw from this?

Populating the railway past

Let us consider a case study. One of the powerful aspects offered by the RWLD project within a museum’s environment is the ability to locate and present stories of individual people. Where related to collection items, it has the potential to ‘personalise’ objects and produce new understandings, of the preserved item and of how it might have been used in service. By way of example, the very mundane – but significant – technology of the shunter’s pole/coupling pole is instructive.

Invented in around 1870, the pole was one solution to a challenging safety problem: casualties caused when workers had to go between wagons to couple or uncouple them. Coupling and uncoupling goods wagons was essential to the ability of the railway network to move freight for much of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It was also a very dangerous activity. Wagons were joined together by strong chain links. Attaching and detaching wagons from each other was a manual task, and it left staff in a vulnerable position, risking being crushed or run over if the wagons moved whilst they were underneath or between. The coupling pole was a stout wooden pole with a metal hook on one end, used to grab a coupling from a position of relative safety beyond the wagons, from whence it could be manipulated to couple or uncouple the wagons. As Klaus Staubermann (2017) has noted, ‘it is the curators’ or historians’ responsibility to interpret and make sense of all objects, whether “exciting” or “boring”. This responsibility comes with the added challenge to keep these collections “alive”, to capture their history and share it with our audiences’. How might it be possible to engage visitors with what is, essentially, a wooden stick with a metal hook on the end?

One route to this might be by personalising the objects, and connecting life stories of the people who once used them. Ann-Marie Foster (2019, 2024) has explored the power of the direct connection to museums’ collections through First World War memorabilia and keepsakes. For most railway items it is not possible to make this direct connection between an individual and their object – but it is possible to find representative examples. For railway tools of the trade, often this can be done via accident records found within the RWLD project.

So, in the case of the coupling pole, we might look to Thomas William Manners. Manners was born in 1866 in Cinderford, Gloucestershire. After stints as a coal miner and general labourer,[3] he joined the Midland Railway briefly, before moving to south Wales and joining the Barry Railway Company as a porter.[4] In 1898 he married Hannah Matthews,[5] and in 1899 he joined the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants trade union as a brakesman[6] – a grade of railway worker, often based in a goods yard, who would apply brakes on goods wagons to slow them down.

From three different sets of records inside the RWLD project dataset, we know that Manners had an accident on 24 March 1905. He was working at Barry No. 2 Dock, riding on the buffers of the eleventh wagon in a train of twelve. As the train moved at slow speed, he uncoupled the twelfth wagon with his foot. He was about to jump down to track level, when he slipped and fell between wagons; the final wagon passed over his left leg, which was later amputated. The official state accident investigation, produced by Railway Inspector J H Armytage of the Railway Department of the Board of Trade, noted that Manners had a coupling pole and ‘he is to blame for not using it’. Armytage also observed that it was ‘common practice for the guards and brakesmen on this railway to ride on the buffers of waggons [sic], and accidents of this nature are likely to occur so long as the practice is permitted’.[7] From the accident record, we can start to understand the context and practices of work on the ground, seeing the lived experience of railway workers which would not otherwise be available to us.

It also raises significant questions about why Manners did not use the coupling pole he had been issued. Could he manipulate it whilst riding between the wagons, in a relatively confined space? Was it too unwieldy? Was it quicker to uncouple the wagon with his foot? If so, was time and pressure to get the work completed an issue? Where (and who) was that pressure coming from? Why was Manners riding on the buffers in this way?

As Inspector Armytage suggested, this mode of uncoupling and working was probably something Manners and others were likely to have done many times before. Did the yard foreman or other superior officer from the Barry Railway Company know what was going on? It seems hard to believe not – so we have potential ways to access the tacit practices upon which the system depended, but which, as Staubermann (2017) notes, were not recorded at the time. Although unanswerable at this distance, these questions still perform a valuable service in allowing us access to aspects of railway history which would otherwise remain obscured.

Combining other formal records gives us different insight into the impacts of these working practices and the accidents. The Barry Railway Company’s records of accidents and compensation, held at The National Archives of the UK and transcribed as part of the Railway Work, Life & Death project, add to the picture. They suggest that Manners was paid just £60.13.9 (c. £7,900 now) in compensation.[8]

This might speak to the way railway companies aggressively defended their financial position. However, that relatively limited payout might have reflected the active agency of Manners in the process. He was a member of the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants (ASRS) trade union. As such, he would have been able to access support from the ASRS in a number of ways. One of these was representation to ensure the Barry Railway paid compensation. From ASRS records, also within the RWLD project, we know that in June 1906 Manners was offered £250 compensation (around £32,500 now). The offer would have been a full and final settlement, effectively discharging the Barry Railway’s responsibility (at law, at least) to Manners. However, the ASRS records show he refused the offer, and subsequently returned to work with the Barry Railway on 2 October as an assistant to the train foreman at £1.8.0 per week.[9] Did Manners see a benefit in keeping in the Company’s employment, in a new capacity, and therefore refuse a lump-sum payment with a view to a new role?

This, then, speaks to ideas of how the railway companies saw themselves as paternalistic employers, providing for their workforces – including in the event of life-changing occupational disability. Railway companies commonly re-employed disabled staff, in roles that were understood (by the expectations of the time) to be better suited to the changed circumstances of the staff member. Cases from the records within the RWLD project, for example, show staff whose roles involved work at track level, such as shunters and guards, and who lost one or more limbs being re-employed as gate-keepers at level crossings.[10]

In Manners’ case, according to his ASRS record, he was employed on light duties in the telephone office from 5 November 1906. The Company paid weekly compensation before his return to work – and half the cost of an artificial leg.[11] Returning to the display of objects in museum spaces, one of the cases in the NRM’s revamped Station Hall includes a prosthetic leg, spotlighting the history of disability. The ability to connect different stages of a life story, via objects, and the potential for the whole to shape visitor understandings of the challenges of railway work, is clear.

In hindsight, Manners’ decision to remain in railway employment seems to have been a sensible one. On the 1911 Census he was listed as a telephone operator in railway service.[12] His union membership record shows that by 1915 he was an assistant foreman,[13] and by the 1921 Census he was a traffic foreman.[14] By the time he retired in 1932, he was the controller of Barry docks; he died that same year. Though focusing on his railway career, his life can be rounded by including his family story, and exploring his community life in south Wales – we know that he chaired the Wyndham Conservative Club, was a member of Barry Church Council and was a chorister at All Saints’ Church, Barry, for 33 years.[15] Possibly most difficult of all to achieve, there might also be scope for personal testimony or contributions from family members, if this could be located.[16] Such life stories give a compelling means of understanding the people behind the objects in a museum gallery, as well as the objects themselves.

Finally, turning the approach upside down and starting with the people found in the RWLD project database allows us to diversify the stories told about British and Irish railway pasts and potentially the voices we hear – in keeping with the approach advocated in this issue of the Science Museum Group Journal by Oli Betts (Betts, 2025). Clearly and importantly the accidents tell the stories of the majority of the railway workforce, working class men – people and stories which can be overlooked in public interpretation. In addition, though not numerous, it is possible to bring to the fore even less well represented groups. This includes women, like level crossing keeper Ada Davies killed in rural Wales in 1922, or signalwoman Elizabeth Trevelyan hurt at Tondu, Wales, in 1917 (Esbester, 2024; Esbester, 2024). It also shows us international workers, like Spaniard Crisanto Rego, hurt at Cardiff in 1916, and Egyptian Mohammed El Zoheiri killed at Walthamstow, London, in 1929. It becomes possible to position a wider range of people and stories in Britain’s railway history (Jolliffe, 2020, Esbester, 2022).

As has been seen in relation to Thomas Manners’s accident, often these accounts raise more questions than answers – but even the act of asking those questions allows better understanding and appreciation of railway pasts. Whether via object or person, the accident stories contained in the RWLD project make it possible to see items in use and practices on the ground. It can recover individual railway workers, whilst exploring a wide range of political and social historical factors that reach far beyond ‘just’ the railways – whether to do with the politics of relations between employer, employee, state and unions, or the challenges of health and safety at work and what happened after an accident, including seeing disability. Diving into the data in this way and posing new questions disrupts and challenges our assumptions around railway worker history, encouraging further discussion and groundwork for new engagement.

Perspectives on collaboration

Katy Bunning et al’s article (2015), exploring participatory practice in a new permanent gallery at the Science Museum, found enhanced engagement, empowerment and expertise-sharing as some of the benefits of collaboration, but concludes by saying more needs to be done, particularly by large organisations, around sharing practice, experience and value in this area. The article details what the Science Museum gained from the process, but the value the participants felt, or not, was outside the article’s scope. Thinking as holistically as possible, therefore, we want to include participant value in our exploration of the RWLD project. But what might ‘value’ mean?

As Eleonora Belfiore and Oliver Bennet (2008) acknowledge, the arts and heritage sector moved to evidence-based notions of value in the 1990s, influenced by medical practice. This has put greater emphasis on outputs and value that is easy to measure. This of course means that those aspects that are harder to record are missed, or potential markers of value overlooked. There is power at play too – does the value have more weight if it is valued at organisational rather than volunteer level? In a different article, Belfiore (2009) makes the point in response to Matarasso’s 1997 report Use or ornament? that research on the social impacts of the arts assumes that there is something that can be measured – ‘it is just a question of identifying it’ – but it is possible the metrics and relationships are just not there (Matarasso, 1997).[17] Research rarely focuses on testing this assumption. This is an important flag to wave. This article does not claim any new metrics for value capture. But as it is a collaborative project, there is legitimate value in exploring what each party gains from the relationship.

It is interesting to consider Kenneth Foster’s view (2023, p 36) on mutualistic relationships here, where success is not judged by individual organisational benefits, but on ‘the benefit that accrues to the community as a whole through the collaboratively created entity’. Emily Pringle (2019, p 153) in Rethinking Research in the Art Museum, makes the case for collaboration too. Pringle states museums can be a collaborative ‘space of experimentation and curiosity, where ideas and knowledge are explored and shared by practitioner researchers working alongside academic and non-academic researchers’. The RWLD project is multifaceted in this way and encompasses each of these ‘types’ of researcher. Acknowledging the value each gain is therefore useful to generate a more representative picture generally.

A strength of the RWLD project is in its ability to adapt and flex, working with new collaborators along the way and responding to unanticipated opportunities as they arise. While it has not been possible to follow up all opportunities, the value in being responsive in this way has strengthened the project’s goal to add content to the data and provided moments of contemplation or development at an individual level.

Volunteer perspectives

We start with the volunteers, without whom the project could not exist. The project has volunteers that work on site or remotely, depending on the organisation. For the Railway Museum, the 12 or so core volunteers work from home and are not expected to visit the main site to do their work. They work at their own pace and at times that suit them around their wider lives. Many of the volunteers have worked in other SMG roles and have an interest in railways and/or the work of the Science Museum Group. Being able to work from home has helped the geographic reach of the Railway Museum, allowing engagement and participation nationally within Britain. This increased access to the Science Museum Group (SMG) volunteering opportunities reflects the observations of Jessica BrodeFrank et al (2021) about the value in removing barriers to participation such as the need to travel. Whilst this project pre-dated and operated in different ways to another SMG volunteer project, Communities and Crowds, the experiences and benefits to all of working with volunteers very much replicates the evaluation provided by Geoff Belknap et al (2024).

In November 2024, a survey was sent to the team asking them to anonymously share their reasons for volunteering and whether they got anything personally from being part of the project. Nina Simon (2010, chapter 10) recommends evaluation of participatory activities to facilitate museum acceptance around this work and as a learning exercise for all involved. So, what did we learn from our volunteers? On motivations, an interest in railways was the most popular driver:

Railways – main motivation

“A desire to contribute a little of my time to railway related projects”

“I am interested in railways and want to help with work like this”

“To help me learn more about the railway”

“Interest in railways”

“Long term interest in railways generally and history and genealogy in particular”

“Interesting railway subject”

With general interest and/or a desire to support the work of the Science Museum Group a second motivator:

Support museum work – secondary motivation

“Several years ago as a library volunteer at the Science and Media Museum we had to give up the work temporarily while our supervisor was involved in a new project. RWLD was offered and I have taken part ever since”

“It gave me an interest for my spare time in the winter”

“The work is extremely interesting”

“To learn more and provide useful information”

“To help with the project and (initially) to have something to replace volunteering at the museum during Covid”

Railway interest is not surprising given that many of the volunteers from the project had previously volunteered, transcribing railway historian Alan Jackson’s subject card catalogue, which specifically asked members of railway societies to help as ‘enthusiast experts’ (Haines and Woodham, 2023). A couple of the replies touch on altruistic aims such as providing useful information or replacing their on-site volunteering. It is interesting to compare their initial reasons for volunteering against the value they feel from the activity. Eleven volunteers responded to the question ‘Have you got anything personally from being part of the project?’ Despite the majority joining the project out of railway interest, railway insight only features in three responses that mentioned railways. The remaining four attribute value to greater understanding at either human or geographical level. This suggests a value in supporting the volunteers to go beyond initial interests in ‘just’ railway history and start to consider much bigger questions about British and Irish society, economy and politics in the past. For the volunteers there are levels of value around depths of knowledge to be gained and feelings of personal wellbeing from undertaking the work. This is comparable to similar archive volunteering, as seen by Tim Causer and Valerie Wallace (2012) and Caroline Williams (2018). In the context of the RWLD project, a sense of satisfaction generated by completing the work, contributing to the project’s ethos and keeping one’s brain active are the personal benefits mentioned. Whilst it remains hard to measure wellbeing in a meaningful way, the details which volunteers have offered show that they are gaining from being involved in the project. Indeed, after the initial run of approximately 4,000 cases had been transcribed, when asked if they wished to continue, the answer was a resounding ‘Yes!’ – and at times it has been hard to keep up with their level of productivity.

There was one particular consideration for the RWLD project it is important to note: the impact of the potentially challenging topic matter on those involved, especially the volunteers. This was a key concern from the outset, considered carefully even before formal ethical opinion was sought (through the University of Portsmouth). Before anyone started on the project, they were given an introduction which covered the likely content – textual descriptions of accidents to railway workers (no images were included in the original records). It was made clear that the project team was available to support the volunteers, and if the content did start to concern anyone, they should stop working on it – as a pause initially, but potentially halting permanently. To date whilst there have been a couple of temporary pauses, the volunteer teams have been keen to keep going.

Value gained – depth of knowledge

“A better insight into [r]ailway safety issues and an opportunity to fee[l] useful by writing articles drawing on the work”

“A greater knowledge of terminology used in the railways and how vast of types of jobs that [sp] were from carriage cleaner and shunter to gatekeeper. Also the wide range of age of the workers from about 12 years of age boys loading fruit on wagons to 80+ year olds men and women gatekeepers”

“Learnt a lot about the history of railways and social attitudes and norms of 100 years ago”

“Although I had little particular interest in the railways, I have learnt a lot about the social history of railway life of the period, terminology and working on a spreadsheet”

“I have found a number of records of interest as they relate to my part of the world”

“Remembering counties before boundary and name changes took place. Also a realisation of the prolific injuries that took place”

“Insights into working conditions, possible family connections”

Value gained – personal satisfaction and wellbeing

One element absolutely essential to the functioning of the project and its ability to keep pace with the volunteers’ enthusiasm and productivity has been the role of the Volunteer Administrator. Drawn from within the pool of volunteers, this role facilitates their work and acts as the first point of contact for the volunteers. Originally held by Craig Shaw, until health concerns led him to step back from the project, the role is now undertaken by Chris Heaton. It involves considerably more responsibility than the other volunteer roles. Chris noted this additional responsibility actually contributed to his engagement with and enjoyment of the project:

“Although we work entirely remotely, I welcome the opportunities for sharing knowledge and information around our common interest with the other team members, and enjoy enabling and supporting their work, shaping the database content to ensure consistency and ease of discovery for users”

This sense of interaction and community is clearly significant and offers the volunteer administrator enough to outweigh the additional time spent on crucial but bureaucratic tasks. Having a volunteer administrator to facilitate the smooth running of a distance-based community project is a model that would work for other institutions considering similar work. For the wider team, the volunteers know they have a peer on hand who can advise and trouble-shoot queries as they arise, and it helps Esbester and Baker to safeguard their time and focus on outputs, collaboration and the project’s direction. To summarise value for this group then, the team have gained a depth of subject knowledge, but in the process have acquired an appreciation of their own value, of their ability to contribute something to society, something that helps them in their own lives either through acquiring new skills or keeping alive existing skills. Helen Graham’s (2016) assertion that ‘knowledge is always produced through interrelationships’ has been borne out for our volunteers.

Science Museum Group perspectives

Turning to the host of the volunteers under discussion – the Science Museum Group – this section of the article considers the institutional perspectives on the value of collaborative volunteering. Several colleagues from the Science Museum Group were asked to give their perspectives on the RWLD project’s value. SMG’s Head of Volunteering, Matthew Hick, picks up on its alignment with SMG’s strategic objectives on digital reach and engagement[18]:

‘Railway Work, Life & Death (RWLD) is a fantastic example of how volunteering has helped deliver on Science Museum Group’s digital ambitions. Building on the success of the pioneering Alan Jackson Archive Project, RWLD has allowed us to scale up our digital reach and impact by enabling volunteers from across the globe to participate in this important collaborative project with the University of Portsmouth. Donating around 3,000 hours a year, they have reviewed thousands of historic accident records to create a valuable research tool for railway historians.’

Research Lead for the Railway Museum, Dr Oli Betts, highlights its importance in generating human stories for the museum. This connects with the SMG’s strategic aim to address gaps in the stories it tells[19]:

‘Human stories are what make the railways, and history more generally, come alive for the vast majority of visitors. With an industry as large and varied as the railways, employing hundreds of thousands of men, women and children at their peak, that human interest has, for so many people, a particular personification – a grandfather, a distant relative, or an uncovered aspect of family history. That is what makes Railway Work, Life, & Death so special. Not only is it a fantastic resource with rich historical detail about the big picture of railway history – it is also full of small personal stories of lives, careers and tragedies that both researchers and audiences feel a profound connection to. I think it offers so much human detail and pathos for the museum, and helps us unpick stories of work, accidents and the afterlives of those moments of disaster, in ways that are intimately relatable for visitors.’

Of personal and professional consideration for Baker is that the project aligns with the ethics of museum and library work: it has a ‘for public benefit’, provides ‘access to knowledge’[20] and strives to be accessible and open to all. These are also personally motivating. Reflecting upon this and the above two comments from SMG colleagues positively affirms the value of the project in its ability to align with core SMG objectives and the purpose of the museum to relate and tell stories.

To delve into this a bit deeper, the NRM is in a period of flux with re-interpreted galleries and new exhibition spaces due to open in the coming years. Telling human stories, not just engineering feats, is a core driver for change[21] around railways’ impact, and the RWLD project has helped to shape content in this area. As a result of the large body of data, it has been possible to derive quantitative information about workers injured, killed, the type of work most liable to result in accident and how the accident occurred. The findings revealed railways’ most dangerous job was shunting – the practice of coupling or uncoupling wagons together to form a train. The most common reason for why was becoming trapped between buffers and getting crushed. The shunters’ tool-of-the-trade was the shunting pole. This pole could prevent such accidents, or could be the cause of them if used incorrectly or defectively. Being able to present such data together for the first time has generated new knowledge and understandings that can be shared with visitors on the Museum floor. The creation of an infographic to represent the scale of death and injury visually is part of the interpretation on the story of rail’s movement of goods. It has also informed object choices, with a selection of shunting poles on display, images and film of shunters at work and, in the display case, a shunter’s prosthetic leg and their personal story of injury.

This is the first time worker health and safety has been told in NRM interpretation. As Esbester (2020) notes the railway worker accident has not been made part of the focus of the public gaze. It received very little attention at the time – as evidenced by worker accidents relegated to appendices of the Board of Trade accident reports – and scant historic analysis made subsequently (Esbester, 2008; Giles, 2011; Knox, 2001). Disparate and large-scale historic records are a further part of the reason for the neglect of railway employee accidents – the data has been extremely difficult to gather and work with. The RWLD project’s dataset is beginning the historic redress and recentring of the much-overlooked railway worker.

But another part to this is the challenge of presenting ‘difficult pasts’ to visitors during a fun day out (Esbester, 2023). If done sensitively, however, Manon Perry and Will Sims and Will Law suggest ‘risky histories’ can challenge visitors in important ways (Perry, 2020; Sims and Law, 2024). Rosenthal (2023) outlines ten useful considerations when exhibiting absence and loss in a museum or gallery setting and these have been applied when appropriate to do so. In particular, ‘Personalising the loss’ and ‘Don’t overlook the mundane’ have shaped our approach to display. The label for the prosthetic leg includes information on whose leg it was, the circumstances around how their leg was lost and what happened next – in this instance, work continued but in a different, lower paid capacity. The ‘mundane’ aspect: the tool of the trade – the shunting pole, as previously discussed, is given prominence on display, with five poles suspended over visitors’ heads, with the instruction to ‘Look up’. Asking visitors to engage in this way invites contemplation and consideration on the simplicity of the pole in relation to its importance in accident prevention. As Belfiore and Bennett (2008) attest, ‘cultural institutions have a role in shaping our understanding of what art and culture are’. The act of selecting these poles for display in a permanent gallery publicly flags their importance in railway history.

These objects form part of the redisplay of Station Hall, a permanent gallery at the Railway Museum. One of the core objectives in planning for this display was to interpret the gallery’s historic sense of place. Despite its name, Station Hall was never a station in the passenger sense of the term. It was a goods depot, a place where freighted goods arrived by train and were unloaded or reloaded onwards via other transport networks. When displaying challenging histories, being mindful of geography and the significance of place in story telling is also important (Rosenthal, 2023). Shunting and inevitable injury were part of the building’s fabric and therefore its inclusion is both authentic to the space and respectful, marking generations of workers’ labour and loss. Rodney Harrison (2012, p 14), when discussing the concept of heritage, acknowledges that places acquire unofficial heritage when they are co-produced with people to create a relationship to the space. Telling this local story and grounding it to place has the potential to create a connection with visitors, particularly those local to York. To reference Simon (2010) again, there is potential for visitor participation around the space; to encourage the sharing of local memory – the goods depot closed in 1972, so workers and their families may still remember the gallery’s previous use.

Taken as a whole, this project has generated content for the Museum to tell new and sometimes challenging stories, formulate new knowledge and reposition the worker and their sacrifice centre-stage in railway history. It also represents a divergence in our approach to storytelling at the Museum, moving away from stories of pioneering engineering feats to more intimate people stories of invention, impact and relatability. Projects like this can add much needed human detail missing in our previous interpretation. As Station Hall has only just reopened to the public (September 2025), time will tell how visitors receive the new approach and the contribution it makes to the Science Museum Group’s practice and understanding of telling challenging stories.

Academic perspectives

At an immediate level, the RWLD project has significant, if relatively traditional, academic value. It is opening up areas of social and cultural history for examination, allowing new and critical explorations of railway, labour, health and safety, and disability histories. It is producing new understandings of those who worked on Britain and Ireland’s railways in the past, as well as the nature of that work. Arguably though, what is more significant is the project’s methodology and collaboration.

Methodologically, the nature of the project as a collaboration between a university and partners outside higher education demonstrates to those within higher education environments the benefits and importance of working collaboratively across sectors. At an individual level, Esbester’s research and practice as a historian has benefitted. Prior to the RWLD project he tended to operate in the traditional ‘lone scholar’ mode, and focus on issues above the level of the individual. The project has refocused his research at the personal level, and he now incorporates collaborative and co-productive methodologies into as many aspects of his research and teaching as possible. To give the first of two examples, he created and coordinates ‘Working with the Past’, a core second-year module on the University of Portsmouth History programmes. The students co-design their project work with external stakeholders, including determining the products they will create and jointly determining some of the assessment criteria.

Secondly, related to the RWLD project, Esbester and a small team of volunteers from the Havant Local History Group have co-created the ‘Portsmouth Area Railway Pasts’ project (Esbester, 2024). Funded by the University of Portsmouth’s Centre of Excellence for Heritage Innovation,[22] the project explores the family and community lives of railway workers in the Portsmouth area, taking as their starting point those found in the RWLD records. Based in the community, the jointly-produced outputs, including a travelling exhibition, are being shared in the local community (Esbester, 2025). These were aspects of Esbester’s practice as a historian which were only nascent before the RWLD project.

At a practical level, collaboration on RWLD makes it possible to access vastly more material than would be possible by any one individual or organisation. It also brings different kinds of expertise into contact, for the benefit of all involved. Over the course of the project, participants have shared their insights into different aspects falling within the project remit, enhancing everyone’s understanding. In particular, the railway knowledge that the volunteers have brought to the project has been crucial. Often formed over many decades of railway enthusiasm, the volunteers have shared their expert understanding of the railways across the project team and in public. This has produced a better appreciation of railway spaces, tasks and people.

Meaningful collaboration is not straightforward work; it is time-consuming to do properly and ethically, and this does not always fit with the relatively short-term financial and results-focused drivers often present within UK higher education in 2025. The pressures and challenges of the sector (felt in the museums and archives sectors too) can push against long-term collaborative working.

So far as the University of Portsmouth is concerned, the project makes an important contribution to its ‘civic agenda’, in terms of how it reaches outside higher education and works with different communities. It helps demonstrate the value of higher education in a more general way, by contributing to life outside universities. And of course, familiar to all those inside higher education in the UK, the project speaks to the ‘impact’ agenda.[23] The project’s collaborative working and the outputs that are flowing from it are providing material that will be used to show how work being undertaken inside a university environment is shaping understanding, attitudes and knowledge far beyond higher education.

Spotting opportunities for using the project in teaching has also been possible, despite not being part of the project’s original plan. Esbester and Baker have worked with masters students and undergraduates from a variety of disciplines in the digital and geographical technologies as well as through the expected history syllabus. This has provided students with valuable experience, which in the longer run will enhance their employability; as one student noted in early 2025, ‘I want to reiterate how much I enjoyed working on the RWLD project in my second year, it was definitely the reason why I pursued a masters/career in public history’.[24] It has produced new ways of looking at the project material, and new outputs, including blog posts, digital mapping and promotional material.

Esbester has also taken discussions about collaborative working, the nature of expertise, and interactions with organisations and researchers outside higher education into the leading academic transport history journal, the Journal of Transport History, in his role as an Associate Editor. These are ongoing amongst the Journal’s editorial board and are important in terms of recognising contributions to the field as widely as possible. Finally, opportunities to work with the current rail industry have arisen during the project lifespan – some of these are discussed elsewhere in this article. It is worth noting here that this offers the unusual opportunity for an explicitly historical project to help shape the current rail industry: using case studies from the past to help inform present practice in relation to health, safety and well-being in the rail industry.

Connecting past and present outside museum spaces

To give one example of the ways in which it is possible for research projects to contribute to communities far beyond physical institutional spaces, in May 2024 work by the RWLD project ensured a relatively large-scale (for workers) incident was remembered and marked at its centenary. This involved the local community, the rail industry, and descendants of those involved in the incident. Without RWLD’s intervention, it is unlikely that the incident would have been known about or remembered.

Unlike the very rare passenger train crashes which have often been marked, sometimes with formal memorials and acts of remembrance, the very-much more common worker casualties have tended to be overlooked (Esbester, 2021). A product of many factors, this means that the far greater numbers of railway employees killed and injured at work have no clear point for remembrance: they remain invisible. Indeed, until the RWLD project, it was extremely difficult to identify staff casualties in a systematic way, and therefore also difficult to appreciate the scale of the issue or to recognise them publicly in some format.

It was recognised that remembering railway employees hurt at work offered opportunities for the RWLD project and its research to reach and work with audiences outside the project’s institutional collaborators. Primarily it would increase understanding of the dangers of railway work in the past and ensure individual employees were named and known. Significantly, it offered the opportunity to do this in the communities in which the original railway employee had worked. However, on practical grounds it simply would not be possible to do this for all of the people in the RWLD dataset.

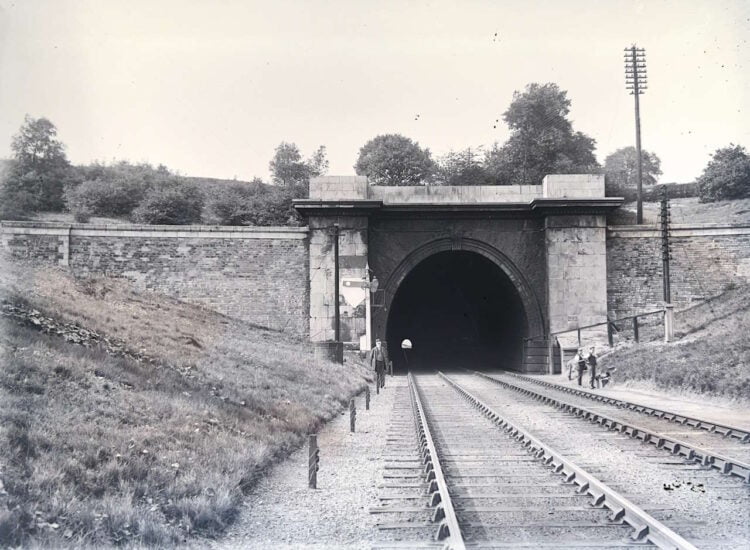

Drawing on past experience of marking centenaries of ‘large-scale’ incidents (including Stapleton Road,[25] Bristol, 1921/2021 and Wilmcote, Warwickshire, 1922/2022) it was apparent that an incident in 1924 also offered potential to take the RWLD project out of museum and higher education settings and into the community by looking at a smaller scale incident (Esbester, 2022). On 24 May 1924, John Cockerill and William Hibbert died at Manton Tunnel, in Rutland; George Buckby, Richard Shillaker and Thomas Shillcock were injured (Esbester, 2024). Shillaker had been filling around 40 lamps with oil, kept in a rough shed close to Manton Tunnel’s south portal (Baillie, 2024). Somehow the oil storage shed caught fire, and a series of explosions followed, sending ‘a huge mass of burning liquid’ shooting out. Shillaker’s fellow railwaymen, working nearby, ran to help, but one of the explosions caused the injuries and fatalities. Clearly this was a very dramatic incident – certainly atypical in its ‘newsworthiness’ and scale. At the time, in the area, it was well-known, but with the passage of time that local memory faded.

In the months leading up to the centenary, Esbester researched the incident and the people involved. This included an element of genealogical work, attempting to identify and work with descendants, as well as local organisations and media. In this, a certain amount of serendipity helped. A request in the local press was seen by the neighbours of the closest living descendant of the men involved. They put Esbester in touch with Dorothy Buckby, the 104-year-old daughter of George Buckby. Dorothy was willing to share her remarkable memories of the accident, including her father’s return home after the incident and his recovery. This interview is available to watch here.

Serendipity also came into play in relation to the rail industry. As many of the men involved in the incident were track workers, they occupied roles which are now the responsibility of Network Rail, the infrastructure owner and manager. Involving the rail industry in any form of remembrance was going to be important, not least as Manton Tunnel and junction remain an operational site. Whilst organisations like Network Rail had been broadly supportive in past work of this nature, they had stopped short of memorialisation. In this case Joe Rowberry, the Head of Safety, Health & Environment for East Midlands Route, Network Rail, was hugely supportive. With colleagues he made it possible to bring together descendants including Dorothy Buckby and the great grandson and great-great grandsons of John Cockerill, the Railway Chaplain for the area, RMT Union representation and media, to mark the centenary (Baillie, 2024).

Subsequently Rowberry arranged for a plaque to be installed at the site of the accident, and the incident was used in Network Rail safety communications to explore the implications for railway staff safety practice today. This picked up on other work that the RWLD project has done within the industry, to embed a ‘useable past’ (Divall, 2012). This includes safety workshops examining past incidents and drawing out learning points, and the production of a track worker safety digest through the Rail Safety and Standards Board and the Infrastructure Safety Leadership Group (available here).

Being able to work so closely with various members of the communities – family, local and railway – and to mark the incident at its centenary was a significant means of taking the RWLD project out of its typical museum and higher education settings and engage with new and different audiences. It took a great deal of time and effort, and some good fortune, so it is not a straightforward model to follow. It offered the different constituents different things, but each forming a route into a past they were largely unaware of; all involved benefitted.

Taking work like that of the RWLD project outside its institutions and to places where people might encounter the railway past is important at any time. This is particularly pressing in 2025, around Railway 200, the rail industry-led partnership initiative marking 200 years since the first steam-hauled passenger journey on the Stockton and Darlington Railway. Elsewhere in this issue of the Science Museum Group Journal Oli Betts offers some critical insights about the power and potential of anniversaries, including Railway 200. He argues that it might be possible to use such popular interest around anniversaries as levers to broaden stories told about the past, present and future.

The Railway 200 initiative has shown itself open to critical reflection upon the railway past, including identifying areas in which difficult topics, like staff safety and accidents, might be addressed. However, the dominant narrative has been celebratory in tone, reflecting the purposes to which the anniversary is being put – in keeping with Vohra’s analysis of the 1875 and 1925 anniversaries of the Stockton and Darlington Railway (Vohra, 2022). McLean (2016) has observed of Flying Scotsman’s preservation in the 1960s that there was a tension between nostalgia and an industry attempting to modernise. The Railway 200 organisers are keen to present the current initiative as future-oriented, with the past playing a limited, supporting, role; yet the feeling of a nostalgic appeal underlies at least some of the presentation of the past. The work of the RWLD project, in highlighting working practices and the dangers of the job in the past, offers a potentially jarring contrast with that nostalgia and the celebratory tone of Railway 200. Nonetheless the RWLD project exposes a crucial topic that should exist inside and outside museums and university spaces.

Conclusions

Long-term collaborative projects, where there are no fixed destinations, that flex and grow, responding to the needs of the collaborators and communities within its environments, can be a good fit for volunteers, museums, libraries, archives and universities, and the communities and stakeholders they work within, with and for. So often collaborations and human connections are short-lived and in response to a time-limited project. Particularly in relation to collaborative projects that reach into communities beyond large institutions like universities and museums, this can create tensions about the ‘cliff-edge’ when a formally funded project concludes. What happens to the relationships established? What happens to the resources created and their maintenance? In sectors where financial and time pressures have been acute for many years, and are only getting worse, the end of a project risks losing the trust built up outside the institution, and opens up questions of extractive relationships, even if they were established with the best intentions in mind. But when projects are not constrained, this paper shows the types of benefit that can flourish.

Recent research on re-energising Britain’s museums points to the importance of long-term thinking and slowing down (Demos, 2025). The value of making time can ‘enable novel and valuable uses of a collection in research and exhibitions’, shown here through new knowledge, new stories, new interpretation and positive social value among collaborators and the wider communities. To quote from Adrienne Maree Brown’s Emergent Strategy (2017, p 27), a reflective piece where she suggests how we can lead and think in ways that are sustainable and collaborative, we need to push back against pressures and constraints and remember:

There is always enough time for the right work.

This is not straightforward, of course, given the multiple competing pressures organisations and individuals face. And it should be noted that an open-ended, collaborative project like RWLD has only been possible thanks to the dedication and enthusiasm of all of the people involved. The involvement of volunteers giving time, energy and expertise is not unproblematic, of course, in terms of equity, diversity and sustainability. Within RWLD we have worked with these issues by always trying to act ethically, including by centring the volunteer experience, recognising and respecting their expertise and contributions, and by ensuring the project is giving them something that they want.

The value that has been created by the project – by the people at the heart of the project – and discussed in this article suggests that it has offered enough to all involved, people and organisations, to continue. Some of the value has been more straightforward to articulate than other aspects, and for many groups who use what the project is creating, we may never hear of its value to them directly. As more and more tangible outputs are created, including the Station Hall display work, the number of beneficiaries of RWLD project research will continue to increase.

Empowering people beyond the formal bounds of the project to make use of its resources is extremely significant. In recent months we have seen a number of examples of how this can work in practice, often supported by the project though not formally a part of its work. This includes individual railway workers, made visible by the project, being recognised in their communities. The better availability of knowledge about and details of worker accidents contributed to the memorial plaque installed by the RMT Union and Transport for Wales at Hereford station on 2025’s International Workers’ Memorial Day (28 April).[25] History Points is an organisation installing QR codes across Wales to connect people with their local history. Included in its railway content are cases from within the RWLD project.[26] The Friends of Weaste Cemetery, in Salford, have used details from the project to enhance their knowledge of people buried in the Cemetery (Kilvert, 2025). Alstom and Transport for Wales are using RWLD project work in current staff safety initiatives.[27]

Some of the wider community initiatives have a direct connection to Railway 200. In March 2025, a theatre company local to Southampton put on a performance at Bitterne station. ‘Stories from the Station’ explored local people’s relationship with the railway and its history; they included within it three accidents they had selected from the RWLD project (Esbester, 2025). And Southeast Communities Rail Partnership have included London, Brighton and South Coast Railway carman William Betterton amongst their Railway 200 ‘blue plaques’ scheme, at Littlehampton in West Sussex;[28] he is also now featured in Littlehampton Museum’s permanent railway display. Without the RWLD project Betterton would not have been visible. It is clear, therefore, that even though the topics raised by the project are often challenging, it has been and is possible to engage in constructive dialogue and to bring these untold histories of railway work and railway workers to light. The more comfortable we are with considering and acknowledging the difficult parts of our railway pasts, the better and more inclusive our understanding will be, and the more it will be possible in the future to address past inequities and tell neglected stories.

Embedding collaborations between academia, libraries, archives and museums as well as communities, volunteers and even industry shows how working together can create extraordinary experiences. Marcum (2014, p 79) notes this by saying:

It is not just education that LAMs [Library, Archives and Museums] can extend. Particularly with museums in the mix, they can extend experiences – experiences of the beautiful, the rare, the poignant, the extraordinary, the amazing, the stimulating, the provocative.

Perhaps what is needed across the sectors is the permission to take time to explore, to deepen our connections and to share what we find with the rest of humankind.

Acknowledgements

While we have not named individual contributors here (following discussion with them that elicited a range of opinion on the issue) we do gratefully recognise and thank all of the Railway Work, Life & Death volunteers for their time and effort – without them, the project would not be possible. We are also grateful to all those who have been part of this work over the years, to those who continue to into our present and to those who may be in our future. Thank you.

We recognise our institutional support, in particular from the National Railway Museum/Science Museum Group and University of Portsmouth, as well as from the other organisations involved in the Railway Work, Life & Death project. Our thanks also to the Science Museum Group Journal editorial team for their patience.