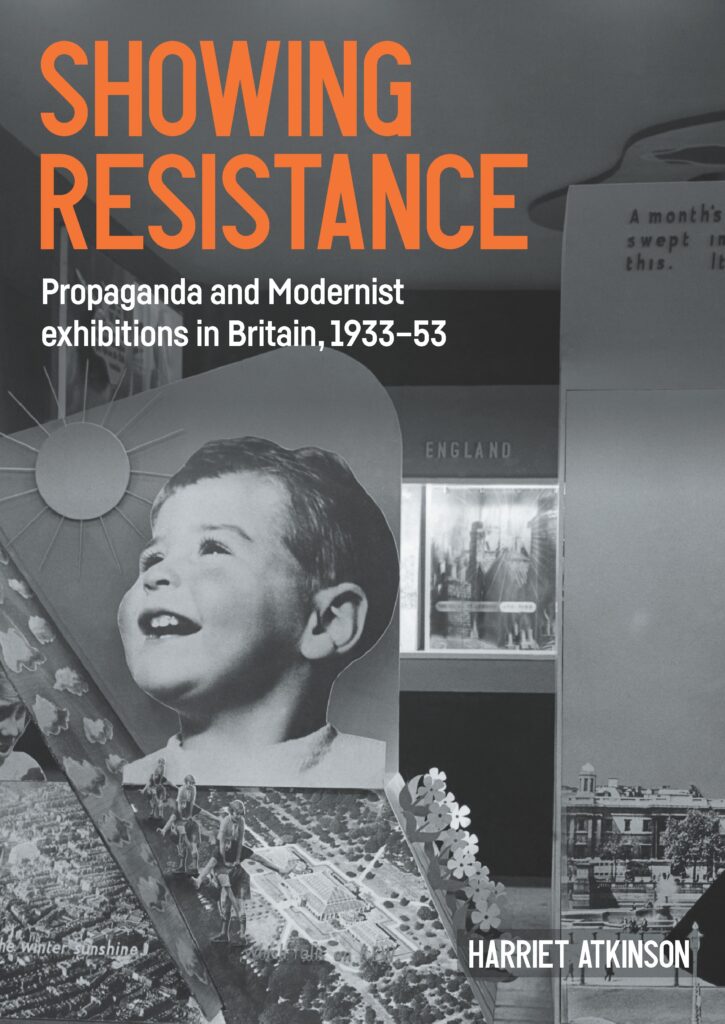

Book review: Showing Resistance: Propaganda and Modernist exhibitions in Britain, 1933–53, by Dr Harriet Atkinson

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/252303

Abstract

Scott Anthony, Deputy Head of the Research & Public History Department at the Science Museum in London, reviews Harriet Atkinson’s book Showing Resistance: Propaganda and Modernist exhibitions in Britain, 1933–53.

Keywords

book, book review, Britain, British history, communications, propaganda, public history, Second World War, world war two

By the end of the Second World War, Britain had developed a startling new approach to exhibition making. ‘The use of exhibitions as a method of propaganda for ideas has suddenly blossomed’, as the designer Misha Black put it, ‘from a frail plant into a vigorous growth which now spreads its tendrils from Oxford St and Piccadilly to provincial towns, remote villages and isolated army camps.’

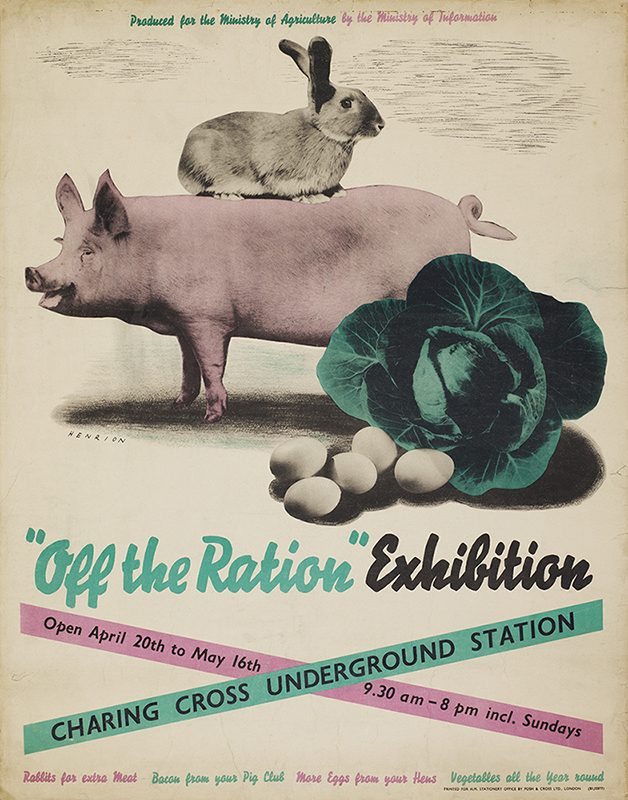

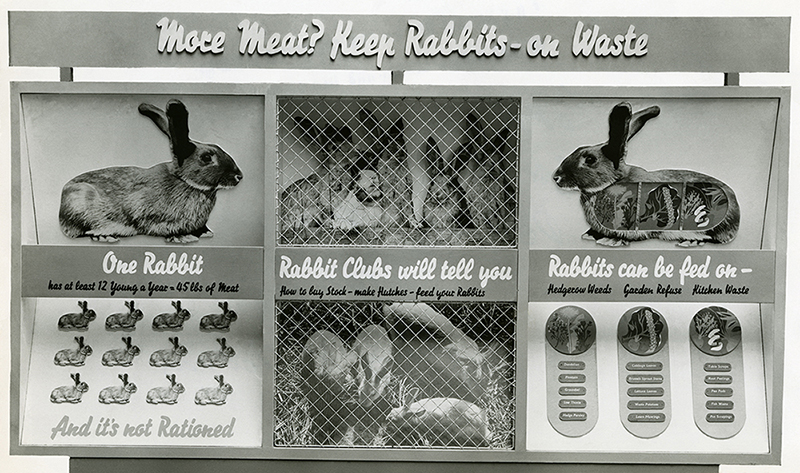

‘Propaganda exhibitions’ was the name given to the temporary pop-up exhibitions which had begun to populate urban areas during the inter-war period, and which provided the inspiration for their rapid expansion in wartime. According to Black, the striking displays he had produced for the Ministry of Information (MoI) had created a core of informed opinion that ‘spread as widely as a contagious disease’.

While we might be wary of taking Black entirely at his own word, his boasts were not without foundation. Like his brother Sam Black – an ophthalmologist and founder of the Institute of Public Relations – Misha tirelessly established, built and propagated new organisations throughout his career.

Harriet Atkinson’s Showing Resistance: Propaganda and Modernist exhibitions in Britain, 1933–53 illustrates the professional rise of Black’s generation of designers and exhibition makers, as a wave of inter-war experiment was eventually codified into something like established practice by war. By recounting this story of evolving practices, Atkinson also shows how the fashion for propaganda exhibitions led figures like Herbert Read, Nan Youngman, and the toymakers Paul and Marjorie Abbatt to develop expansive new approaches to arts education.

One of Atkinson’s objectives is to trace the international influences on ‘British’ design. This is a book about a generation of designers (figures such as Ernö Goldfinger, Otto Neurath and Lazlo Maholy-Nagy feature prominently alongside Black), more specifically a story about a generation of émigré – often Jewish – artists and designers, attempting to secure a professional foothold in 1930s Britain. ‘Propaganda exhibitions’ became an important vehicle (or not) for this larger process of social, political and cultural integration.

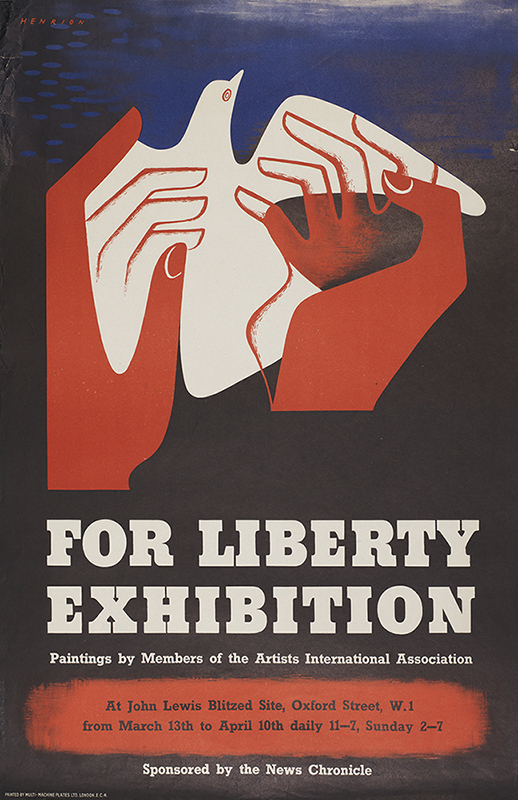

Dominated by photography, the bold use of graphics, and illustrative models, ‘propaganda exhibitions’ were a mode of exhibition making that could encompass salesmanship (there was a substantial crossover with the dressing of shop windows), political publicity and social campaigning. Sponsored by media outlets such as The News Chronicle, as well as organisations such as the Milk Marketing Board and National Smoke Abatement Society, the exhibitions became a site of immersive multimedia experimentation. As Atkinson says, although it is difficult to assess how important or influential this deluge of temporary exhibitions was, we can use them to track the formation of important and interesting approaches and networks. These exhibitions, supported by booklets, radio programmes and short films, created visual idioms that would influence the cultural and informational environment from Picture Post magazine to post-war BBC television.

Although Showing Resistance often implies that propaganda exhibitions harnessed political energy ‘from below’, this aspect of the book’s argument is not particularly convincing. The popularity of now iconic exhibitions such as London Pride, Dig for Victory and America Marches cannot easily be separated from their immediate wartime contexts. The stark contrast between the bombsites outside and (for example) the hopeful and ordered world of the MoI’s exhibitions in bomb shelters gave them visceral power. The experience of the Blitz in particular encouraged a blurring between viewer and subject that was the sine qua non of the successful propaganda exhibition. The heighted emotions and imaginative solidarities amplified by propaganda exhibitions arguably depended on the heighted and totalising experience of war.

In the 1930s it seems more accurate to say that the propaganda element was important in connecting the émigrés into existing networks of social and political patronage. Atkinson’s assorted modernists were mostly unable to convince the greater public of the virtues of flats and other ‘designs for living’, but were able to find reformers of various political stripes interested in modernist solutions to problems such as pollution, public health and town planning. Whitechapel Gallery – then still demonstrably informed by a philanthropic ethos – provided one of the format’s few institutional homes.

While propaganda exhibitions at Charing Cross Station were well positioned to capture the attention of Whitehall, the relatively prosperous British working class remained mostly uninterested and confident in their own tastes. The niches of British corporatism – modernist radios for listening to the BBC, Bakelite telephones for the GPO – provided rare opportunities for alignment between modernist designers and objects that appealed to public taste.

Equally, proponents of the propaganda exhibitions tended to draw heavily on examples from the Soviet Union or radical German politics, and many designers who appropriated their immersive and directive styles operated in loose sympathy with their politics. In terms of alignment with international causes, exhibitions and activism for peace in the early 1930s became advocacy for Spain, rearmament, and the Popular Front in the mid-1930s. Unsurprisingly, the coordinating bodies behind these exhibitions, such as the Artists International Association (AIA), found themselves accused of (at best) being at the beck and call of the Soviets.

While left wing affiliations were highly visible in the 1930s, how conscious or deeply felt these values were is open for debate. While Atkinson tends to celebrate the ‘progressiveness’ of the designers, their politics don’t always seem particularly substantiative. Understandably their ‘politics’ often demonstrably mattered less than their status as professional designers. McKnight Kauffer worked for the Peace Pledge Union, but he also designed a book for Oswald Mosley. During the war, the AIA was commissioned by the British government to produce an exhibition For liberty: paintings on war, peace and freedom, to promote a speech by President Roosevelt.

Indeed, by the end of the book, the coalitions between artists, architects and writers that the exhibitions of the 1930s had brokered were already being absorbed into the extended networks of the cultural Cold War. Arguably one terminus of the ‘propaganda exhibitions’ Atkinson describes is the touring exhibitions of the Marshall Plan: object-light travelling shows made possible by US government support for initiatives such as the Magnum photographic agency.

It was sincere and politically committed figures like John Heartfield that suffered the most from these shifting alliances. Pushed to the margins after arriving in the UK in 1938, Heartfield’s powerful anti-Nazi propaganda was deployed by the MoI at the height of the Blitz. Yet he was kicked out of the country when the war was over – there were no Wernher von Brauns in the art world, apparently.

There is a current trend in post-war British historiography keen to re-emphasise that, while the power and coordinating capacity of the British state grew enormously during the war, the majority of industry remained in private hands. In other words, the semi-socialistic compact forged in 1945 was much less statist than is generally assumed. One interesting but underexplored aspect of Showing Resistance is the extent to which the networks of private enterprise visibly underpin the MoI’s propaganda exhibitions: from Boots the chemist to Rootes car showrooms, industry enabled government propaganda exhibitions.

The varied imaginative commitments of the 1930s quite clearly depended on an unpredictable mix of civic, state and industrial patrons that gradually faded from prominence during the post-war era, and without fully recognising this inheritance the ‘politics’ of the exhibition propagandists can seem quite flimsy – little more than the response of the modernist great and the good to a variety of bad things happening. The post-war expansion of the welfare state further pushed these modes of cultural engagement to the philanthropic margins. At the start of his career Black was a proponent of the propaganda exhibition, by the end of it he was putting together shows such as Design for the Needy at the RSA.

The book closes in the mid-1950s, with the designers of wartime propaganda exhibitions apparently following Richard Levin from the MoI into television, where they began designing sets and camera set-ups for the immersive worlds of an integrative emerging technology. Yet the careers of figures such as Black and Milner Gray, which are central to Atkinson’s book, would not reach their zenith until the 1970s. From 1959 Black served as the inaugural Professor of Industrial Design at the Royal College of Art. Not only was he an effective advocate for design and design education, Black also helped give shape to the new worlds of post-war mass mobility by bringing high aesthetic standards into aviation, railways and shipping. An émigré generation that bowed out around the Silver Jubilee begat the last modernist relics of a land before globalisation, hyper-liberalism and punk.

Readers can download an Open Access edition of Harriet Atkinson’s Showing Resistance: Propaganda and Modernist exhibitions in Britain, 1933–53 here: https://www.manchesterhive.com/display/9781526157423/9781526157423.xml

Atkinson’s film about art during wartime, Art on the Streets, is screening daily until May 2026 at Tate Britain’s Marie-Louise von Motesiczky Archive Gallery. A trailer is available below: