Challenging museum narratives: the case of a Rhodesia Railways carriage

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/242207

Abstract

Science Museum Group (SMG) object 2005-7446 was built by a British rolling stock manufacturer in 1927. It was exported as a first-class passenger coach to British-administered Southern Rhodesia (present-day Zimbabwe) and ran on the lines operated by the former Rhodesia Railways. But, in 1974, the carriage was on its way back to Britain, overseen by the artist, conservationist and railway enthusiast, David Shepherd. After being displayed at a series of locations across Britain, the carriage was acquired by the National Railway Museum, part of SMG, in the early 2000s. It was kept in storage until 2024.

With the carriage now on display at SMG’s National Collections Centre in Wroughton, this article asks what stories it has the potential to tell. It argues that interpretation of the carriage since its repatriation has focused on the story of its return, while gaps in the knowledge of its operational life – including the experiences of passengers and the impacts of the railway’s labour hierarchy – have been overlooked. By tracing the carriage’s archival trail in Britain and consulting SMG’s technical files, this paper highlights the importance of foregrounding such untold narratives. It concludes to suggest ways forward for future research, interpretation strategies and the management of associated files.

Keywords

Africa, British Railways, colonial history, David Shepherd, Museum, railway history, Rhodesia, Zambia, Zimbabwe

Introduction

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/Many of the objects that can tell us about Britain’s colonial history are kept in museums. The most well-known cases are the subject of longstanding debates about repatriation and national identity, while lesser-known examples, unless the subject of media controversy or academic research, are sometimes overlooked altogether (Hicks, 2020; Kuper, 2024). Some of these objects contain ‘hidden’ histories, or narratives that are obscured or lost, until there is a conscious effort to recover them (see Messner, 2014; Parry, 2021). This risk of obscurity applies especially to objects kept in museum storerooms. These spaces, typically closed to the public and offering limited access to external researchers, house objects that are not displayed on the museum floor (see Geoghegan and Hess, 2015; Corona, 2024). For those familiar with the practical challenges of museum work, it is unremarkable to point out that objects in store receive less attention than their counterparts on display and that, consequently, less is known about them. Yet, it is noteworthy that this is especially true of colonial-era objects in store, particularly in relation to records management (see Turner, 2020). In this sense, museum storerooms, some of which became dumping grounds for imperial propaganda as empires came to an end, are no less infused with colonial legacies (Aldrich, 2020, p 160). Work is therefore required to understand more about storerooms and their objects, both for what they can tell us about the colonial past as well as the museums that house them.

Science Museum Group (SMG) object 2005-7446, a former Rhodesia Railways (RR) carriage, is one example of a colonial-era object in store. Built by a British rolling stock manufacturer in 1927, it was then exported to Southern Rhodesia (present-day Zimbabwe) where it operated on the extensive RR system. In the 1970s, it was brought back to its country of origin by renowned British artist, conservationist and steam enthusiast, David Shepherd. Once back in Britain, the carriage was displayed at several locations before being accessioned into the National Railway Museum’s (NRM’s) collection in 2005.[1] The carriage was placed in storage after being restored in 2008, but with one obvious detail missing from its livery: the ‘Rhodesia Railways’ lettering on each side of the vehicle. In 2024, as part of the SMG’s One Collection project, the carriage was moved to the newly constructed, state-of-the-art open storage facility, the Hawking Building, at SMG’s National Collections Centre (NCC) in Wroughton. With just under five per cent of SMG’s objects being on display, the NCC is the main store of SMG’s collection, holding 350,000 objects.

Bridging the functions of a museum and a storeroom, the Hawking Building houses a range of objects on an open-plan grid. While these objects do not include traditional methods of interpretation, such as accompanying text or display boards, an access team regularly escorts visitors around the grid and gives an insight into a small number of select objects. The Hawking Building has accommodated public visits on selected dates since its opening in 2024, when the carriage became viewable to the public for the first time in nearly 25 years.

Notwithstanding the carriage’s large size compared to other objects on the Hawking Building’s grid, it is a particularly important object of analysis because of the significance and connotations of the term ‘Rhodesia’. For many Zimbabweans, the name is an unwelcome reminder of the colonial, white minority rule past.[2] Its history is tied to that of Cecil Rhodes, after whom the historical region of Rhodesia was named. Rhodes was the founder of the British South Africa Company (BSAC), which administered Northern Rhodesia (present-day Zambia) and Southern Rhodesia (present-day Zimbabwe) from the late nineteenth century until the expiration of the BSAC’s royal charter in 1923, when the former territory fell to British authority and the latter became a self-governing colony under white minority rule. Through the BSAC, Rhodes encouraged the construction of several railways in Southern and Central Africa. He was an active promotor of, and later became associated with, the Cape-to-Cairo railway project, a scheme first envisaged in the second half of the nineteenth century but never carried out to completion. The route was intended to traverse the African continent from south to north as a way of linking territories under British administration. For Rhodes and the BSAC, railways were a financial investment intended to generate returns through the transport of goods and raw materials exported from former British-administered territories such as Rhodesia (see Lunn, 1992). The process of extraction that enabled this often relied on violence, the appropriation of land and the exploitation of former colonial subjects, the legacy of which contributes to the ongoing controversies surrounding Rhodes and his association with institutions such as the University of Cape Town and the University of Oxford’s Oriel College (see Beinart, 2022; Day, 2023). The call to decolonise these institutions, along with the similar demands made of heritage organisations, underscores the present research as particularly timely.

This research is not without its methodological limitations. Funding and time constraints have limited the scope of this research to published material and British-based archives and organisations, while a more comprehensive project would involve fieldwork and access to archives in Southern and Central Africa. Nevertheless, this article demonstrates how museums could use a limited source base to begin to reveal the hidden histories of colonial-era objects in store.

To do so, the article begins by explaining how SMG typically holds information about its objects. It then outlines the carriage’s history, including what is known about its operational life and how the story of its repatriation has dominated its interpretation since. It moves on to analyse why the carriage was acquired by SMG in 2005 before using published sources to consider other stories that the carriage could tell. Finally, it highlights the problems encountered when researching the carriage’s history and, with reference to the absent lettering, considers how its current display further obscures its past. The article concludes with a reflection on its limitations and potential ways forward for SMG and other heritage organisations that hold similar objects.

How museums hold information about their objects

Just under five per cent of SMG’s objects are on display, meaning that the vast majority are kept in store. An object on display will usually be accompanied by interpretation, such as a label or text panel, where museum visitors can engage with its story. Objects in storage do not receive the same treatment. SMG’s efforts to digitise its collection are an attempt to address this gap and make its collection more accessible, as part of a strategy named ‘Open for All’. Among other things, this strategy is intended to ‘remove barriers to engagement with the SMG collection’.[3] This initiative is complemented by a more recent strategy that seeks to respond to the relationship between the legacies of SMG’s collecting practices and colonial history (see Barringer, 1998). A document setting out the strategy states that SMG can ‘better serve our audiences by addressing gaps in the stories we tell’.[4]

Removing barriers to engagement and addressing gaps is difficult for museums partly because of ingrained collection development practices and systems. For many of its objects, whether on display or in store, SMG holds documentation in the form of a physical file, referred to by SMG staff as a ‘technical file’. The main purpose of a technical file is to inform museum staff about a file’s corresponding object. A technical file can include anything from physical characteristics, such as an object’s height and width, to correspondence with donors or commissioned research. However, there is little uniformity; some technical files are more substantial than others, while many objects do not even have a technical file. Although curatorial staff are constantly researching their collections, the vast number of objects in museum storerooms means that remedying this disparity is an unenviable, never-complete task. What is contained within technical files is also very rarely standardised because items are added at the discretion of curators. Usually, a technical file will at least include information about an object’s acquisition. However, some information about a given object does not ever make it to a technical file. This information might be hidden in research papers or simply stored elsewhere, such as in shared curatorial drives or retained in curators’ heads. As Sarah Longair (2016, p 6) points out, discussions around curatorial decision-making are typically unrecorded. This is especially true of verbal discussions, a main form of communication between museum staff. Many insights about an object might be shared in these exchanges, but this information and layers of important detail rarely make it to technical files. This is understandable given the amount of information that museum staff deal with in day-to-day life, but failing to capture these discussions means that key context for objects is often lost; it cannot be referred to by future researchers or made accessible for public audiences. Other difficulties arise when knowledgeable curators become responsible for a different collection or, worse, when they leave the institution altogether.

The object: the carriage and the gaps in its history

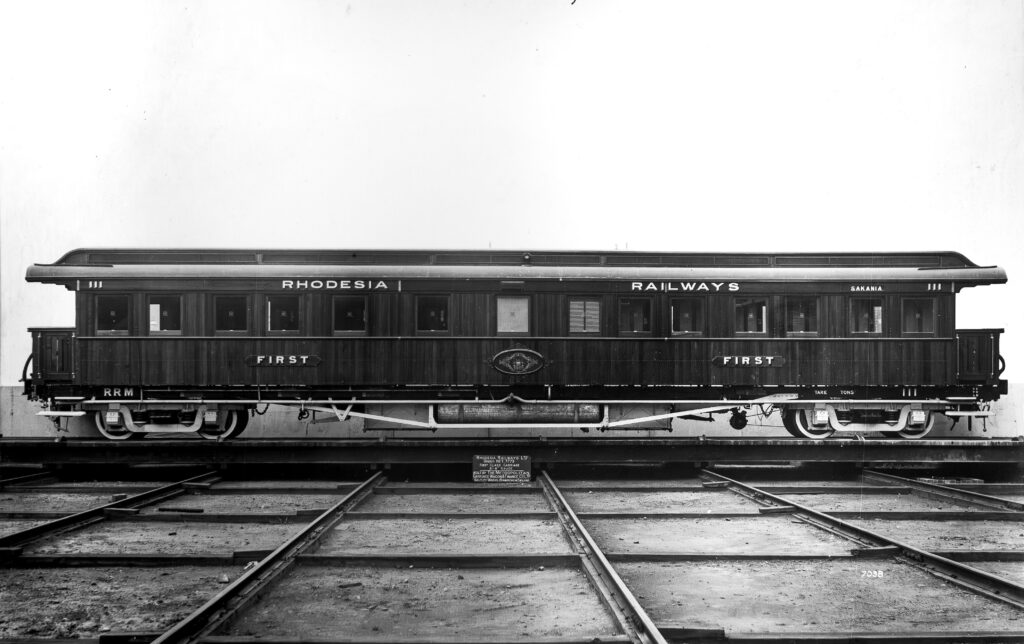

Some of the above challenges arose when researching the carriage in question. As a result, there is uncertainty about what SMG knows about its timeline. For example, previous research commissioned by the NRM suggests that it was ordered from Metropolitan Carriage, Wagon and Finance Company, a Birmingham-based rolling stock manufacturer, in around 1928.[5] However, photographs of a carriage built as part of the same order suggest that its construction date is actually 1927 (see Figures 1 and 2).[6] The carriage was later exported to Southern Rhodesia (present-day Zimbabwe), where it entered service on the RR network for first-class passengers, an affluent, white travelling class (see Winchester, 1935a; 1935b). At some point, supposedly in the 1930s, it was converted to a composite first- and second-class coach.[8] Separately to this conversion, but for reasons as yet unknown, the carriage’s underframe and running gear were replaced by a set manufactured by Gloucester Railway Carriage and Wagon Company. It is believed that this set was originally used for fourth-class coaches which, instead of class markers, carried labels that read ‘Natives’, an offensive, explicitly racist term commonly used by whites in Britain’s former African colonies to distinguish themselves from those of African origin or descent (see Fitzmaurice, 2017, pp 14–18).[9] By late 1971 the carriage had been retired from the RR network and had begun a brief period of operation on the Zambezi Sawmills Railway (ZSR), a logging railway near Livingstone in Zambia.[10]

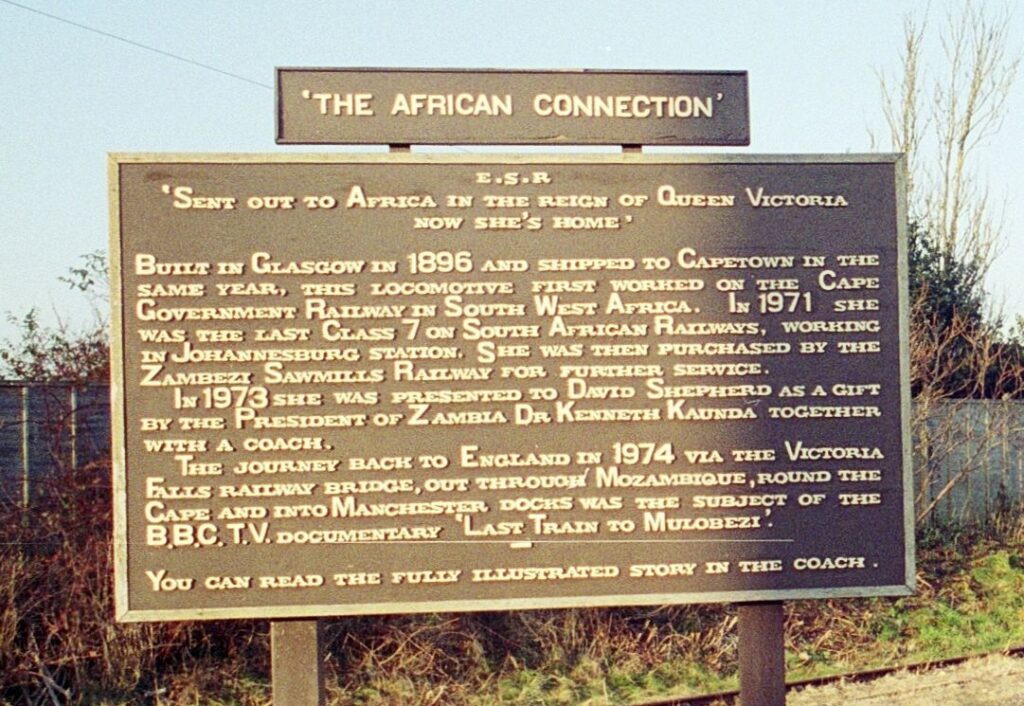

Partly due to the profile of artist, conservationist and steam enthusiast, David Shepherd, the story of the carriage’s journey back to Britain from Africa is well-documented. According to Shepherd’s autobiography A Brush with Steam, he was invited to Zambia in 1964 to produce 12 wildlife paintings for the new Zambian government. During the trip, he befriended Kenneth Kaunda, then-President of Zambia, among others. When Shepherd’s railway enthusiasm became known to his new acquaintances, they advised him to visit the ZSR. He did so three years later. By the early 1970s, he had returned several times, including on one occasion to film the BBC documentary Last Train to Mulobezi for its Taste for Adventure series (Shepherd, 1983, pp 157–58).

The documentary, which was filmed in 1974 and aired in 1975, introduced British audiences to ZSR and the carriage in question, as well as the account of its return. Narrating the documentary’s opening scenes, Shepherd claimed to have heard about ‘an old steam locomotive in Zambia that needed saving’. He was then seen hurriedly jumping out of a car before being helped onto the carriage as it pulled away from an unknown stretch of railway track in Zambia. The documentary proceeded to highlight the quirks of the ZSR, such as its improvised methods of construction and the fire hazards arising from a combination of engine sparks and the use of uncovered timber wagons for passenger services before 1958, when the railway acquired coaches (BBC TV, 1975).[11] When filming in Zambia had concluded, having apparently grown fond of the rolling stock featured in the documentary, Shepherd asked the ZSR if he could have two locomotives and the former RR carriage. Although similar carriages were commonplace on the ZSR by this point, Shepherd believed that, in Britain, the carriage would be ‘unique’ (BBC TV, 1975; see Figure 3). With Kaunda’s backing, the ZSR approved Shepherd’s request (Shepherd, 1983, pp 181–84).[12] Kaunda also wrote a letter permitting one of the locomotives (SMG object no. 2005-7445) and the carriage to cross the Zambia-Southern Rhodesia border, which would otherwise have been prohibited by the trading sanctions enforced in response to Ian Smith’s Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI), a statement that declared Southern Rhodesia to be an independent sovereign state, to international condemnation (Shepherd, 1983, pp 185–88).[13] The carriage and one of the locomotives finally made their way from Bulawayo in Southern Rhodesia to the Port of Beira in Mozambique, a former Portuguese colony. Jack Hayward, a British eccentric nicknamed ‘Union Jack’ due to his enthusiastic nationalism, funded the final leg of their journey back to Britain in 1975 (Shepherd, 1983, p 191).[14]

The carriage’s onwards journey from Manchester docks in 1975 to the NRM in 2005 has been recorded in less detail, but its archival trail was easy to follow. Considering the carriage’s poor condition when it was accessioned into SMG’s collection, it was unsurprising to discover that it had mostly been stored outside since its return to Britain. This includes a 15-year stint at Whipsnade Park Zoo, a wildlife park located in Bedfordshire – the carriage’s first home upon its return – before relocation to Shepherd’s own heritage railway line in Cranmore, known then as the East Somerset Railway (ESR). Consequently, the carriage had already deteriorated significantly by the time it was moved to covered storage in a disused railway tunnel owned by Bill Parker’s Flour Mill workshop in the Forest of Dean.[15] By this point, the locomotive that had been repatriated along with the carriage was in an equally sorry state, having been kept outside the former Bristol Empire and Commonwealth Museum (BECM) and used as a fire assembly point. Shepherd’s replica Ford car – converted by the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers and exhibited at both Whipsnade and Bristol – was set alight by vandals in the BECM’s car park.[16] Ironically, then, Shepherd’s vehicles faced a greater risk in the care of British heritage institutions than they perhaps would have done if they had remained on the ZSR in Zambia, from where they had apparently previously ‘needed saving’ (BBC TV, 1975).

Eventually, the carriage and the accompanying locomotive entered SMG’s collection in 2005, after Shepherd formally offered the pair to the NRM in 2003. This may have been motivated by Shepherd’s personal connections with the NRM. In 1955, Shepherd painted inside a locomotive roundhouse that would later become NRM’s Great Hall (Hewitt, 2017). He was also well known to NRM staff and within heritage railway circles more broadly; his artwork had entered NRM’s collection as early as 1979 and his acquisition of several British Railways locomotives and coaching stock was part of the leading role he played in the steam preservation movement of the 1970s.[17]Before the NRM acquired the carriage and locomotive, Shepherd had sent the Head of the Museum a copy of A Brush with Steam, highlighting the chapter on the carriage’s return to Britain from Zambia.[18] Interestingly enough, according to correspondence between NRM staff, Shepherd’s offer to donate the locomotive and carriage was later accepted on the basis that these objects would enable the NRM to ‘tell the story of the railway’s role in the British Empire’.[19] Ahead of their restoration in 2008, it had been planned to display the vehicles together in NRM’s Great Hall as part of a larger refurbishment named ‘NRM Plus’. The carriage was set to feature alongside the locomotive ‘[at] the heart of a new display’.[20] This was also scheduled to include a collection of RR crockery, donated by Shepherd several years later, which would have apparently enabled the NRM ‘to set the carriage in more than one time period’.[21] However, this plan never came to fruition, as the broader NRM Plus initiative was later shelved due to a lack of funds (see Adams, 2011). Along with the carriage’s size, deterioration and unconventional gauge, the scrapping of NRM Plus led to the vehicle being relocated from NRM’s sister museum, Locomotion, to SMG’s storage facility in Wroughton, the NCC.[22]

Our research to fill some of the gaps and how it was conducted

As alluded to above, SMG holds little information about the carriage’s operational life up until the 1970s. While several comprehensive volumes offer detailed accounts of the railways in Southern Rhodesia, these otherwise informative histories do not touch on the lives of those who used the railway system (see Nock, 1971; Croxton, 1982). As this carriage was originally built for first-class passengers in 1927, it can reasonably be assumed that it was intended to cater for a large influx of white settlers that arrived in Southern Rhodesia between 1924 and 1928 (Mlambo, 1998, p 127). Yet, beyond this assumption, the voices of the passengers who would have used this carriage during its time on the RR network are largely missing.

As Aparajita Mukhopadhyay (2023, p 6) reminds us, focusing on the lives of individuals who negotiated the institutional practices of colonial railways ‘can provide glimpses of motives and actions that may otherwise be lost’. Mukhopadhyay (2023, p 11) goes on to explain that this approach also offers vital insights into how those systems operated, as well as information about how transport users navigated the exclusionary practices that were often reflected through them. Uncovering the experiences of these passengers, as well as RR workers and those who encountered the railway in other ways, is therefore necessary to understanding how railways in Southern Rhodesia functioned beyond ‘tools of Empire’ (see Headrick, 1981).

Responding to Ian Phimister’s (1981, p 79) assertion that ‘it should never again be possible to write a history of [Rhodesia’s] railways which…omits all but the most cursory references to labour, whether Black or White’, academics have already begun to establish how the racial policies of the South Rhodesian government were reflected though the railway system and affected RR employees. For example, Jon Lunn (1996, pp 79–80 and 118–9) explores how the ‘colour bar’ led to depressed wages for all railway workers but adds that Black Africans who worked on the railway were paid significantly less than their white counterparts, and were therefore disproportionately affected by RR’s low pay. Lunn goes on to explain how Black African railway workers were also prevented from acquiring skilled positions by RR’s management, who limited most promotions to white employees.

As outlined by Kenneth Vickery (1998; 1999), Black African railway workers did not simply accept these discriminatory policies. Their grievances culminated in a strike in 1945, when a promised increase in wages and living standards failed to materialise at the end of the Second World War. Changing rural-urban dynamics during this period meant that male workers were increasingly joined by their women and children dependents, but housing provisions were inadequate and cramped. Drawing on testimonies collected at the time, Vickery (1999, pp 54–57) explains that pay was issued partly as rations, while food provisions were not only insufficient for a worker and his wife and/or children but also unfit for human consumption. Other grievances included the limited mobility offered by railway work, especially in comparison to the opportunities granted to white railway workers. More recently, Friedrich Ammermann and Nicole Sithole (2024) have extended the scope of this research beyond the workforce to examine how railwaymen and their kin worked around RR’s exclusionary practices in the physical space of the railway compound.

Further research into the passenger experience would afford us additional insight into how Black Africans navigated RR’s discriminatory environments and begin to address some of the gaps in this carriage’s history. For example, while racial segregation was not a formal policy on RR, Black African passengers in Southern Rhodesia were often in effect subjected to a kind of ‘petty apartheid’ when this carriage would have been in operation.[23] Because this practice operated outside of formal regulations, records do not accurately reflect how frequently it occurred. However, some acts of protest have left a paper trail. One instructive incident on a RR train from Bulawayo to Salisbury in Southern Rhodesia caught the attention of the Rhodesia Herald in October 1957. The article drew on the account of a Mr J R D Chikerema, Vice-Present of the Southern Rhodesia African National Congress (SRANC).[24] Along with other SRANC officials, Chikerema had tried to reserve seats in a third-class carriage on a RR train. A RR staff member had denied the request, insisting that reservations were only possible for second- and first-class trains. However, after requesting a second-class compartment, the officials were told that the second-class compartments were full.

The officials then sent a taxi driver to RR with a written request for a second-class compartment. In the letter, the officials stated that the booking was for three Europeans, who went by the names of N George, C J Roberts, and M Peters. The reservation was accepted. When the SRANC officials boarded the train, they found themselves sharing the compartment with a white European passenger. A RR conductor, when realising that the officials had disguised their identities, asked the officials to move. They refused, prompting the conductor to find an alternative compartment for the white European passenger instead.[25]

The incident was later picked up by Jasper Savanhu, the MP for Angwa/Sabi and one of 12 Black MPs for the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, who wrote to the Herald the following week. While accepting that RR may have made an ‘irresponsible’ administrative error, he stressed that the incident ‘was not an isolated case’ for Black Africans using RR trains. Drawing on his own experience before becoming an MP, Savanhu claimed that RR had often said that trains were ‘full’ and he was told to ‘[c]ome and find out’ if there were any cancellations. He recalled being surprised to find that, when there were cancellations, trains were largely unoccupied, and this happened ‘[o]n most occasions…on a supposedly full train’. Noting that he had not come across a ‘full’ train since becoming an MP, he argued that Black Africans should not have to become MPs to get fair treatment when booking tickets.[26]

Beyond published sources, archival research to find out more about the lives of those who might have encountered this carriage during its operational history was limited by the financial and time constraints mentioned above. Consequently, the archives and organisations consulted as part of this research were selected and prioritised by their accessibility and association with the carriage. In addition to SMG’s technical files stored at the NRM, these included the library and archive of the Zoological Society of London (ZSL), and Bristol Archives.

Surprisingly, there was no information on the carriage’s operational life at the ZSL’s Whipsnade Park Zoo, the carriage’s first home upon its return to Britain, nor at the ZSL library, which holds some of Whipsnade’s records. These only contained information about the carriage’s arrival at Whipsnade in 1975, in addition to a photograph of its official opening ceremony in the following year (see Figure 4).[27] There were some brief references to how the carriage was displayed on a siding beside Whipsnade’s narrow-gauge line, known as the Whipsnade & Umfolozi Railway (W&UR), along with the locomotive that was repatriated at the same time and the adapted Ford railcar designed to imitate those used on the ZSR.[28] But, overall, the display seems to have focused on the account of the carriage and locomotive’s return to Britain, the main narrative to date.

At the ESR, the carriage’s next home in Britain, the vehicle was part of a display focusing on the carriage’s short life on the ZSR and its subsequent repatriation (see Figure 5). This is perhaps unsurprising given that the ESR, then known as Cranmore, was Shepherd’s own heritage line. More unexpected, however, was the fact that Bristol Archives, the repository holding the records of the former BECM, presented similar findings. The BECM had planned to display the carriage along with the locomotive that Shepherd also repatriated from Zambia, now on display in NRM’s Great Hall. Although the carriage never made it to the BECM before it closed amid controversy in 2008, documents exchanged between BECM staff and Shepherd refer to the carriage as ‘1808 “Zambezi Sawmills” Coach’, suggesting that the Museum would have defaulted to the approach taken by Whipsnade Park Zoo and the ESR.[29] In other words, the carriage would probably have been displayed as a rescued ZSR carriage, rather than a former RR vehicle, because the BECM records make no reference to the carriage’s history before the ZSR.

Similarly, SMG’s technical file for the carriage contains minimal information on the carriage’s history before it was encountered by Shepherd. The file mostly contains a series of emails that discuss plans for the carriage’s conservation. While the NRM had commissioned a research paper to address some of the gaps highlighted by this current study, it concludes with few definite answers as to where or how the carriage operated pre-1974. With little confirmed evidence on which to base the carriage’s interpretation, SMG’s limited engagement with this carriage’s history has so far leaned on the story of its journey back to Britain.[30]

Frustratingly, SMG’s current approach to displaying the carriage risks detaching it even further from its former life as a working vehicle in Southern Rhodesia. As already alluded to, the carriage underwent restoration and conservation care in 2008, before it was relocated to the NCC. The restoration was carried out by Appleby Heritage Centre, a company based in Cumbria that specialised in railway conservation. As illustrated in a specification diagram that NRM sent to the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, the ‘Rhodesia Railways’ lettering, which was in place when the vehicle was acquired (see Figure 6), featured in plans for ‘how it [the carriage] will eventually look’.[31] These plans also included a set of RR crests, which were missing from each side of the vehicle when it was acquired by NRM in 2005. Surprisingly, when the carriage was relocated to the Hawking Building in 2024, ephemera that included stencils, transfers (SMG object 2005-7446/7) and spare RR crests (SMG objects 2005-7446/6 and 2005-7446/8) were found in one of the carriage’s compartments. The discovery further implies that re-applying these features was always part of the restoration plan, even if it is unclear whether these features were intended to be added by Appleby Heritage Centre, as part of ‘[i]nternal and external refinishing, painting and varnishing’, or by SMG at a later date.[32] Either way, when the carriage left Appleby Heritage Centre, both the ‘Rhodesia Railways’ lettering and the accompanying RR crests were missing (see Figure 6), and this remains the case at the time of writing. One NRM curator suggested this is because the project ran out of time and funding, but there is a clear question of priorities; the cost of re-lettering the carriage and re-attaching the crests would have been comparatively small against the total cost of restoring it in 2008.[33] Failing to correct this when the carriage was moved as part of SMG’s One Collection project in 2024 – when the stencils and plaques were discovered – was a second missed opportunity. But the omission of the lettering, previously the most obvious way of identifying the carriage, raises a particular problem. Compounded by the Hawking Building’s lack of physical interpretation, this former RR vehicle now appears to SMG visitors as ‘a rail carriage’, anonymous, with no information or clues about its past use (see Figure 8).

This current display therefore overlooks the carriage’s significance as a colonial-era object more than any previous display of this carriage in Britain. It not only obscures details about where it originally operated, but ensures the carriage’s identity remains hidden from visitors. The display also goes against the focus on ‘additions, not subtractions’, as recommended by SMG’s own guidelines on its display of colonial objects.[34] Unless already familiar with the carriage or the ‘RR’ logo embossed on its windows (see Figure 9), or otherwise informed by an SMG tour host, visitors to the Hawking Building would be forgiven for not even realising that the carriage worked overseas. There is little hope, then, that visitors to the NCC will be able to learn anything about the vehicle’s former life in Southern Rhodesia or those who may have encountered it there.

Conclusion

As this article has highlighted, there are several stories that the carriage has the potential to tell beyond its export from Britain or the against-all-odds account of its return. For example, the story of the passengers who navigated RR’s racially motivated policies could feature prominently in a future exhibition. The industrial colour bar, or the 1945 strike, could be used as a starting point for further research. Digital or future in-person displays, focusing on those who rode the carriage in its final days on the ZSR, could fill gaps in its current lack of interpretation. In other words, through the diverse range of actors who would have encountered it, this carriage could offer a kaleidoscopic view onto many different lives within the former British empire. Pursuing this opportunity would help SMG use the carriage to ‘tell the story of the railway’s role in the British Empire’ in a more comprehensive way than any previous attempt at interpreting it has achieved so far.[35] It would also serve as a reminder to other institutions that a dominating narrative can sometimes conceal an incomplete history, and this might prevent an institution from representing the full history of an object.

This article has also identified two limiting factors which may have prevented these avenues from being explored before now. The first relates to records management. Much of the research carried out for this project was not original but had to be repeated and cross-checked due to unreferenced and conflicting records, mainly in the carriage’s technical file. In addition, helpful information and research leads were gleaned from curators who, while knowledgeable about the carriage, had not recorded vital details about its history. This meant that some useful sources were discovered at a late stage. Standardisation and specification of what should be held in SMG’s technical files would prevent this from recurring while also resulting in greater consistency. In practice, this might be as straightforward as a document that, for each object, contains a brief biography, an outline of its history, and key contextual information. If such a document had been included in the carriage’s technical file, it would have saved time that was used to establish basic facts, such as when the vehicle was built or when it arrived back in Britain. This is not an issue that is isolated to SMG, but is rather a product of the scale and diversity of museum collections and the lack of resources to appropriately contextualise them. There is therefore a limit to how feasible it would be to retroactively standardise an entire collection; for the tens of thousands of technical files that SMG holds, this would clearly be impractical. Efram Sera-Shriar (2023, p 319) recommends a targeted approach, advising museums ‘to begin at a smaller scale with specific objects, and work outwardly’. Conducting similar small-scale ‘hidden histories’ projects for other colonial-era objects would help SMG understand the scale of its knowledge gaps and how far its documentation processes need to change – a necessary first step for any museum seeking to meaningfully address structural issues of inaccessibility (Mears and Modest, 2012, pp 301–5 and 307). As Hannah Turner (2020, p 190) reminds us, ‘records are the starting point of all of this work’.

A second impeding factor to carrying out this research was that the recorded information about the carriage is dominated by its association with David Shepherd and its journey back from Africa in the 1970s. Consulting the carriage’s technical files revealed that SMG has limited information on how the carriage was used for the first fifty years of its life, while even less is known about the RR staff who may have worked with it and the passengers who may have travelled in it. This project’s time and funding constraints meant that efforts to fill these gaps largely depended on published sources and selective visits to archives in Britain, but remedying this will involve more geographically ambitious research; the people and resources key to understanding this carriage’s history are likely to reside in Zambia and Zimbabwe, including in the railway museums of Livingstone and Bulawayo. The museum in Bulawayo holds a significant amount of archival material on RR, some of which is likely to be relevant to this carriage (see Burrett, 2022). Simbarashe Shadreck Chitima (2022, p 215) highlights the risk of deterioration to paper-based materials in these museums, but this potential hurdle nevertheless underlines the urgency and importance of attempting to carry out this research.

One potential next step would be for the NRM to establish partnerships with these institutions, as it has done already with other overseas railway museums, such as the Sierra Leone National Railway Museum in Freetown. An initial collaborative project between the NRM and institutions in Zambia and Zimbabwe could act as a springboard to a long-term working relationship that prioritises knowledge exchange and resource sharing. This could include the collection of oral histories, focusing on those who may have used the railway system, to add to the testimonies collected after the 1945 strike and existing memoirs about RR (see Wright, 2005; Rukovo, 2021). As this article has suggested, SMG does not have sufficient knowledge about the object and its history while these voices are missing, and British institutions are unlikely to have the resources or networks to carry out this work independently. This carriage is a case in point: failing to capture information and establish links at the point of acquisition has led SMG to fall back on the appeal of British-built objects and ‘miraculous’ narratives of return (Withers, 2011, p 247).

The carriage’s repatriation is a feel-good, comforting story told by a well-loved patron of steam, which is no doubt why it has sufficed for so long. But enabling new perspectives and challenging dominant narratives on the museum floor is surely necessary if ‘hidden histories’ projects are to become anything other than fleeting reflections driven by short-term funding opportunities (Mears and Modest, 2012, p 307). As Sera-Shriar (2013, p 319) observes, a key part of fulfilling the long process of museumization to decolonisation is ‘bringing to the fore different perspectives, and introducing audiences to the ideas, values, practices and so forth of extra-European cultures, thereby showing the diversity of human existence on equal ground’. When museums begin to allow self-reflexive critique to change their embedded institutional practices, they can work towards inclusive storytelling while continuing to fulfil the vital role they play in safeguarding and steering public history. In doing so, they might find ways to cater for the diverse global audiences that many now purport to serve.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Catherine Elliott Weinberg, Laura Humphreys and Oliver Betts for helpful feedback on earlier versions of this article. Thanks also go to the anonymous reviewer who offered valuable comments. Finally, thank you to the archivists and library staff who shared resources and information on the history of this carriage, especially those at Bristol Archives, the British Overseas Railways Historical Trust, the National Railway Museum, the Great Whipsnade Railway Archives, and the Zoological Society of London Archives.

This work was supported by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, grant reference AH/W002957/1.