Commemorating the past, shaping the future: the jubilee and centenary celebrations of the Stockton and Darlington Railway

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221708

Abstract

This paper examines how and why communities connected to the railways celebrated anniversaries of important moments in the industry’s history. It focuses on the jubilee (1875) and centenary (1925) anniversary celebrations of the Stockton and Darlington Railway (established 1825) by railway companies, workers and local communities. While these anniversaries were used to symbolically affirm a continuity in railway history, they occurred under different organisational conditions – 1875, during the heyday of multiple smaller companies and 1925, during the consolidated control of the amalgamated ‘Big Four’. A comparative study of these commemorative events reveals continuities and changes in the construction of railway history, and corporate and community identities. To demonstrate this, the analysis will focus on narrative construction, temporal interplay between the past, present and future, and the role of agency. Conveyed through a series of commemorative ‘components’ (Papadakis, 2003), these elements converge to establish the shape and function of the events, and highlight the motivations of different groups for celebrating the past, how commemorative narratives were developed for select audiences, and what vehicles were used to carry said narratives. These core narratives concertinaed elements of the industry’s past, present and future, and were deployed to validate cultural values, draw together communities and consolidate political or economic loyalties. Overall, the paper will demonstrate how and why different stakeholders create and foster commemorative cultures, and critique and measure the efficacy of the forms and functions of this performative engagement with railway history.

Keywords

business history, celebration, commemoration, corporate history, corporate identity, heritage, identity, local history, localism, material culture, memory, railway history, regional history, Remembrance, Stockton and Darlington Railway, Technology

Introduction

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/[E]very fifty years since it opened in 1825 the Stockton and Darlington Railway has been celebrated publicly as the pioneer of all subsequent railway development…and as the harbinger of a technological revolution by virtue of its employment of locomotive haulage (Kirby, 1993, p 1).

On 27 September 1825, engineered by George and Robert Stephenson, the steam engine Locomotion No. 1 took the nine-mile trip from the Mason Arms in Shildon to St John’s Well in Stockton, drawing 33 wagons filled with coal, flour, workers, as many spectators who could hold on, and the railway coach Experiment carrying committee members and officials.[1] This moment marked the opening of the Stockton and Darlington Railway (S&DR), and for some, this very small and now largely defunct line signalled the beginning of the railway age as the first passenger railway in the world.

Despite what has developed as a popular narrative of the S&DR, it was not the first public railway line, the first to be sanctioned by parliament, nor the first to use a steam-powered engine (Heaviside, 1912, p 14; Kirby, 1993, p 1). However, as argued by Jack Simmons (1980, p 4), its flaws and limitations were equally as important as what it achieved. It demonstrated what improvements could be made by engineers, the S&DR company, and other companies that would be established around the world. Though some consider this line to be only the precursor to the real first modern railway in the world, the Liverpool and Manchester Railway (L&MR), which opened five years later, the underlying features of the S&DR – a steam-powered engine for conveying passengers and freight – mean many have and continue to view this railway as the beginning of what Britain continues to rely on for a large proportion of its transport. 1825 has therefore been an important historical moment to measure commemorative events from for nearly 200 years, with commemorative events held at 50-year junctures since 1875. Current plans for the bicentenary organised by local authorities, interest groups, museums and corporations to name just a few will likely be the most extensive celebrations of British railways past, present and future.[2]

Its crafted historical importance was a result of the perpetuation of the myth that it is the first railway in the world, with celebrity personalities, both human and material, acting as instrumental vehicles for carrying these messages through commemorative practices. While the 1975 and 2025 celebrations have and will continue to move away from this ‘first in the world’ narrative, this origin story was central in the jubilee and centenary anniversaries. In 1875, Britain’s railways were a complex network of operating companies of varying sizes and importance. The NER, created in 1854, absorbed the S&DR along with many other smaller lines in 1863 (Emett, 2000, p 89). In 1923 the railways were amalgamated into the ‘Big Four’ – Great Western Railway (GWR), Southern Railway (SR), London, Midlands and Scottish Railway (LMS), and the London and North Eastern Railway (LNER) (Mullay, 2018). This shift meant that by 1925 the NER, and as such the S&DR, were part of the LNER. With these amalgamations, the anniversary celebrations were headed by the successive owners of this section of the national network, and consequently the S&DR’s origin story became a part of these larger, company histories. This paper examines the corporate celebrations of the S&DR in 1875, organised by the North Eastern Railway Company (NER), and in 1925 by the London and North Eastern Company (LNER), as well as challenges to these company-led commemorative practices, to examine how and why this narrative thread was woven into these events.

Railways and commemoration

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221708/002Commemorative practices of the railway industry sit at the intersection of histories of technology and social and cultural memory studies. Though there is a substantial amount of research on railway history and commemoration separately, few scholars have examined the role of this type of cultural memory connected specifically to this industry.[3] Further, where it has been examined, it has been situated as one part of broader areas of study, such as Christine Macleod’s analysis of the celebration of British technological heroes (2007), or Ben Roberts’ examination of the uses of local civic ceremonies in the North East of England (2014).

Literature critically analysing the S&DR anniversaries directly is also rather sparse. In one of the most extensive examinations of the opening of the S&DR and its jubilee and centenary anniversaries, Ben Roberts (2014) argued that these events were steered heavily by the railway companies, who valued the commercial output of the celebrations above developing the local expressions of civic pride and fostering the area’s social identity in connection with the industry.[4] Further, in an article questioning which anniversary should be celebrated as a ‘first’, Jack Simmons (1980) analysed debates over the credibility of the narrative of the sesquicentenary celebrations of the S&DR (1975) and the L&MR (1980). Finally, from a business history perspective, Maurice Kirby (1993) recognised the importance of the commemoration of the S&DR in developing and cementing the commercial images of NER and LNER.

Our two anniversaries sit within a critical period of the development of these types of commemorative practices. Identifying that commemoration is a ‘modern innovation’ that became a common practice in the nineteenth century and continued well into the twentieth century, Roland Quinault argued that what he termed the ‘cult of the centenary’ was the product of both fashion and competition, where the staging of centenary events led to a ‘snowball effect’ and other communities began to emulate and provide greater spectacles through the celebration of the past (1998, p 303, p 321). Further, Thomas Otte noted that the development of European centenary commemorative events from the late nineteenth to early twentieth century was the result of ‘the increased interest of the later 19th-century publics in the past’ and a ‘secularization’ of the time and cultural memory (Otte, 2017, pp 1–2). Additionally, in Gegner and Ziino’s, The Heritage of War, which examined how cultural memory has been shaped by war, the collection of essays demonstrated how subsequent practices used to remember this history, and different versions of narratives it gave rise to, ‘compete[d] for dominance’ in different regional, national and global contexts (Gegner and Ziino, 2012, p 14). The first two celebrations of the S&DR were therefore situated in a time where commemoration was a critical tool to support cultural memory, but were unique in their focus on the history of a new and growing industry.

A useful comparison for how performative memory functioned in the British railway industry more specifically can be found in Lynette Spillman’s Nation and Commemoration (1997). Her examination of commemorations in the relatively nascent nations of the United States and Australia found that national identity was understood as both a ‘version of the past and a vision of the future’ (Spillman, 1997, p 68). Further, these nations expressed identity in terms of their progress since important ‘founding moments’ in the past from which they could predict a trajectory of the same type of progress into the future (Spillman, 1997, p 69). As an industry that was, at the time of the jubilee and centenary, within the first 100 years of its history, commemoration was used as a tool to express the progress that had been achieved since its earliest achievements in the nineteenth century to solidify its position in the present as an important and relevant modern invention, and to further suggest how it would continue to develop into the future.

This paper will critique how organisers of the celebrations developed and used this origin narrative since 1875 through large-scale commemorative practices to cement bonds and identities, and to market themselves to their audiences.[5] It will show how select narratives were used to demonstrate both a continuation of the quality of their work from the earliest of railways, as well as showcase the new and improved versions of the industry at each commemorative juncture. Using a range of similar or enhanced commemorative components which fed into successive commemorative practices, the railway companies used the past to underpin their corporate identities for strategically selected audiences, while other communities and their representatives used techniques to challenge or change these ‘official’ narratives.

Three separate though interlocking themes define the forms and functions of these performative practices: the construction of narratives; the temporal interplay between the past, present and future; and the agency behind the development and use of commemorative cultures. The celebrations will be analysed through a different lens than previous scholarship. The paper will examine how the narratives about the past, present and future of the railway industry were constructed by the organisers for their selected audiences, and how these narratives were supported, conveyed and pulled together using different commemorative ‘components’ (Papadakis, 2003, p 253).

Thinking about the different elements as ‘components’ is useful in analysing the construction and solidification of these narratives. The combination of different ‘components’ of a wider commemorative narrative – be this within a single event or type of commemorative media, or across different geographical or temporal locations – function to ‘articulate a certain story’ (Papadakis, 2003, p 253). The reworking of these components can form a narrative based on the same ‘history’ but with different consequences for its purposes and reception (Papadakis, 2003, p 254). Commemorations of elements of the past can be characterised by large temporal breaks between purposeful activations of the past, but also by more sustained public recognitions of, and engagements with, the past over longer periods of time. This approach provides a useful framework for understanding the construction of commemorative narratives, and the components therein, allowing for a consideration of both original historic sources and any preceding cultural outputs and products. This paper will examine how the core narratives were transferred across different commemorative components within one event to reinforce the messages the anniversaries were aiming to convey, and how narratives and styles of commemorative components from one event were reused in different temporal and/or geographical contexts. The recycling and reworking of narratives and commemorative practices allowed the organisers to tailor the anniversaries for their own agendas and audiences while building on established historical narratives of the S&DR.

Commemorative events are built from the ‘goals or objectives’ organisers aim for them to achieve (Frost and Laing, 2013, p 11). The symbolic meanings of the celebrations differ over subsequent commemorative periods as the organisers shape narratives about the past both to reflect their own identities and situate the past in the present for their selected audiences (Frost and Laing, 2013, p 11). The organisers of the respective anniversaries used a series of commemorative components to convey and solidify their central narratives to appeal to their selected audiences. Though tailored to their specific temporal and geographical contexts and their chosen narratives, there were commonalities in the types of components employed. Both the jubilee and centenary organisers used components that worked in tandem to support the central narratives, while the centenary drew links back to the styles and functions of the former, jubilee celebrations. Commemorative events, written material and moving and static objects worked in combination to support and thread together the narrative of the history of the S&DR and the railway companies.[6] In conjunction, these separate components conveyed and reinforced the narrative that has been crafted by the organisers. The style and narratives of these components were reused and reformed for each of the following anniversaries, but the surrounding economic, social and political factors affected the way they were reshaped. The following analysis of the anniversaries will critique and measure the efficacy of the forms and functions of this performative engagement with railway history by the companies, local communities and workers.

Jubilee, 1875

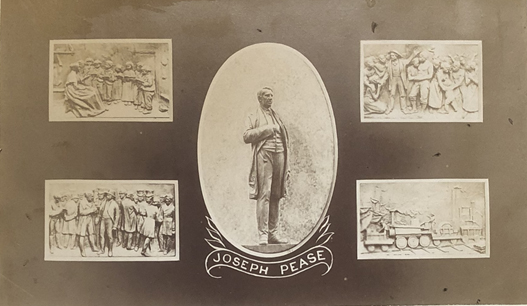

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221708/003The jubilee celebrations of the S&DR in 1875 were spearheaded by the directors of the NER. A committee comprised of well-known men from the Darlington branch of the NER was created to organise the celebrations, including several members of the Pease family, who worked in conjunction with the Darlington Town Council and Joseph Pease Memorial Committee (Hoole, 1974, p 14; Jeans, 1875, p 3). Arguing that the operation and use of public railways began in their town, Darlington Council felt it was their ‘duty’ to be involved in NER’s plans for the anniversary.[7] The Joseph Pease Memorial Committee’s plans for the unveiling of a statue of Joseph, an active promoter and director of the S&DR, in Darlington predated the S&DR preparations. However, this ceremony was almost immediately added to the programme of events for the jubilee (Jeans, 1875a).[8] In this adjusted context, the statue aimed to demonstrate how the Peases were consistent key players in the history of the railways from 1825–1875 by memorialising a member of this regionally famous family in line with S&DR jubilee (Roberts, 2014, p 168).

Roberts argued that although the localised and civic nature of the celebrations was inferred through these events, they primarily acted as vehicles for national and international economic and political gains (Roberts, 2014, chapter 5). As the main organisers of the celebrations, the NER used the history of the S&DR and its jubilee as a platform to craft a positive and progressive narrative showcasing their public and professional identities.[9] Further, as stated in The Railway Times article, though the locality was as important as the physical space where the S&DR had been conceived, ‘the names most honoured were those of the men by whom it had been reared and nurtured, and whose sponsorship and care had ensured its success’ (Railway Times, 1875, p 949). The central narratives were therefore used to celebrate the progress of the railways since the opening of the S&DR as well as the people who had enabled its creation and development, largely at the expense of the region and its ‘unknown’ inhabitants.

The audience for the commemorative events was chosen carefully by the committee. Invited guests included regionally, nationally and internationally important political and economic people. Local reporter, J S Jeans, who was entrusted with writing a history of the S&DR and the jubilee celebrations, listed the guests as:

chairmen and secretaries of all the principal railway companies in the world, the members of Parliament, bishops, mayors, and town-clerks on the North-Eastern system, and the principal industries in the North; and last, but not least, the members of the present Cabinet, and the members of the Government of Mr Gladstone (Jeans, 1875b).

Further, in his banquet speech, Henry Pease described the group of invited guests as ‘comprised in its influence and extent a larger representation of the wealth, the commerce, and the national progress of England than had probably ever gathered outside the house of Parliament’ (Leeds Mercury, 1875, p 5). Those invited from the railway companies across the Britain and Ireland were chosen on the basis of their economic importance, with the number of representatives permitted to attend the celebrations from each company based on their capital and shareholders being given free passes to the events, and international representatives were invited from European, Asian and North and South American railways.[10]

Local people and railway workers were only permitted to participate in a small proportion of the jubilee events. Shown in programmes and personal accounts, this included public processions and the unveiling of the Joseph Pease statue, and decorating the town for the invited guests (West, 1876). Events were also arranged to include the local people in Darlington to celebrate the jubilee separately from invited guests. As will be later explored, the irony of holding the local people at arm’s length in events that celebrated the heritage and achievements of the locality was not lost on commentators of the anniversaries. Further, the types of entertainment organised by the jubilee committee were chosen to most effectively convey core narratives about the NER’s economic and technological strengths primarily for their invited guests.

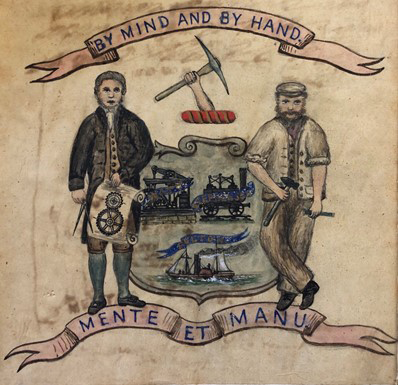

To prepare for their visitors, the town was ‘dressed’ for the occasion with floral arrangements, bunting, signs, illuminations and an ‘Avenue of Venetian pillars that stretched along Victoria Road’, each one ‘capped with a large banner’, much of which was prepared by the local people of the town (Jeans, 1875, p 8; West, 1876, p 7). One of the NER banners was entitled ‘Pioneers of Railway Enterprise’, with the names Stephenson, Meynell, Flounders, Pease, Kitching, Gilkes, Mewburn, Dixon, Backhouse, and Macnay on side scrolls (West, 1876, p 9). These men were instrumental in the founding of the S&DR, demonstrating that business acumen and engineering skill were important features of the narrative. While some of the banners created by local people had simple phrases, including ‘Knowledge is Power’, and the double entendre phrase ‘Take Care of No. 1’, others were more intricate. Decorations by Theodore West, a draughtsman at the North Road Shop in Darlington, included a banner that celebrated engineering and innovation (Figure 1) hung at the Railway Institute on North Road (West, 1876, p 9). The illustrations lauded particular engineers: Watt for inventing the stationary engine; Stephenson for the locomotive; and Fulton for introducing steam navigation. Further, the visual combination of historically important figures celebrated the ingenuity of the engineer and the technical skill of the builders.

NER-led events and holidays for the S&DR jubilee were held in Darlington from 27–29 September 1875:[11]

Table 1

| Date | Events |

| 27 September | A procession from Darlington’s market place to the North Road Engine Works to open an exhibition to the site of the statue unveiling. |

| An exhibition of locomotive engines and ‘other objects of interest in connection with the railways’. | |

| The unveiling of the Joseph Pease statue organised by the Memorial Committee. | |

| The presentation of a portrait of Joseph Pease to the town of Darlington. | |

| A banquet for their invited guests. | |

| 27–28 September | Two firework displays on the evenings on the respective days. |

| 28 September | ‘Excursions to places of industrial, topographical, or antiquarian interest’ for invited guests. |

| 29 September | A ‘Tea Meeting’ for Sunday School children in Darlington and the neighbouring areas. |

| A ticketed ball for the local people. | |

| 27-29 September | A general holiday for the local people declared by the vice chairman of the NER, Henry Pease. |

Table 1: Programme of events for S&DR jubilee, 1825 (Jeans, 1875, p 305; West, 1876, p 50a; Jeans, 1875, p 36

While the events and entertainments were organised for a combination of the local people and invited guests, the jubilee could be viewed as having three separate parts: the commemoration of Joseph Pease open to all; the celebration of the S&DR and the NER to a select group of invited and influential guests; and finally a holiday period and events for the local people that appear almost entirely separate, aside from the exhibition they could visit, from the railway history celebrated during the jubilee. This muddling of events therefore renders it important to draw a distinction between what components were about the S&DR and NER, what components happened because of the jubilee, and in turn what narratives these components were used to convey. Here we will concentrate on the commemorative components that focused more directly on the history of the railways – the exhibition, the statue unveiling and portrait presentation, and the banquet on 27 September.

Visually displaying technological progress was an important commemorative aspect of the celebrations. One of the most successfully received and widely attended events of the jubilee, the exhibition very clearly demonstrated a narrative of progress from the opening of the S&DR to the NER in 1875. Held in NER’s North Road Engine Works in Darlington, and aiming to emulate The Great Exhibition at Crystal Palace in 1851, the organisers wanted the exhibition to showcase this progress of railway technology commencing with the ‘primitive and simply constructed’ Locomotion No. 1, ‘the father of locomotive engines’, building up to the NER engines from the ‘present time’ that were still running on Britain’s rail network (Daily Gazette, 1875).[12] This included examples of their modern local passenger, express, and minerals and goods trains to highlight the types of rail services NER could offer both locally and nationally by 1875 (The York Herald, 1875). In this context, the rolling stock acquired a new temporary meaning to support the commemorative narrative. This narrative was solidified in a speech by the local MP, Henry Pease, at the exhibition opening as he stood in the cab of Locomotion No. 1:

like many of you who have had very good parents it [Locomotion No. 1] has been succeeded by engines which in some respects exceeded their parent. You…will be extremely interested with the marked progress in the construction of locomotive engines from the time when this was constructed (Daily Gazette, 1875, p 3).

The rhetoric employed suggested an almost human lineage between the S&DR and NER. The remainder of the speech noted the continuing financial and technological strength of the NER (Daily Gazette, 1875, p 3). The exhibition therefore used the narrative of NER’s history since the S&DR as a marketing tool to convince potential economic or political allies of their importance in this industry. Further, both the exhibition and the rhetoric used by Pease illustrated the progression of rail technology since 1825, the continuing success of the NER in the present, and importantly a direct connection between the S&DR and the company in running the line in 1875.

The unveiling of the Joseph Pease statue was a central and heavily attended feature of the jubilee (as seen in Figure 2), celebrating Pease, alongside railway engineer George Stephenson and Joseph’s father Edward, as the hero of the celebrations (Saturday Review of Politics, Literature, Science and Art, 1875). Organised by the Joseph Pease Memorial Committee, and paid for by public subscription, the bronze statue had four panels (see Figure 3) commemorating notable phases of Pease’s career: his commitment to education (top left); his anti-slavery stance (top right); his political and parliamentary career (bottom left); and his entrepreneurial work in the mining and railway industries (bottom right) (Jeans, 1875a, p 18; Northern Echo, 1874).[13] The ceremony included the presentation of a portrait of Joseph Pease to the Mayor of Darlington by the chairman of the Memorial Committee to be hung in the Council chambers (Jeans, 1875b).

There were public and private concerns that there was no clear sense of who or what was being celebrated through this event (Joint Stock Companies’ Journal, 1875; West, 1876). In reference to the speeches, West wrote that there was a ‘rather awkward mixing up’ of whether the unveiling was celebrating Joseph Pease or his father Edward and other railway pioneers (West, 1876). Further, in one of many critiques of the celebrations in the press, the Joint Stock Companies Journal, a publication aimed at business investors, stated that the jubilee was ‘not [about] the opening of the railway, nor its celebration after half-a-century, but the smiling visage of the City potentate that will have “marked an epoch”’ (Joint Stock Companies’ Journal, 1875, pp 650–651). This memorial was used to consolidate and retain the Pease family’s power, Liberal politics, nonconformist religious beliefs, and both theirs and Darlington’s industrial and financial prowess, which sat uneasily within the narrative of the S&DR anniversary.

Though the railways were only one aspect of Pease’s statue, the ceremonial opening perhaps says more about how the NER wanted this memorial to fit into the story of railway development. For example, the Duke of Cleveland, whose predecessor was a staunch opposer to S&DR being built through his land and nearly grounded its creation, agreed to officially unveil the statue (Joint Stock Companies’ Journal, 1875, p 650). He spoke very highly of the opening of the S&DR by Edward Pease and George Stephenson, and the work Joseph Pease undertook to ensure its continued success:

although this anniversary is rightly celebrated with the pomp and circumstance becoming its importance…it is right to recollect the services of one who has been so deeply connected with the [railway] system; and I feel confident that it is no empty pageant, but that all those who attend to-day bear in mind the character and the services of Mr. Pease. They assemble to-day to bear testimony to the services rendered alike to his townspeople, to the county at large, and to the country (Jeans, 1875b).

Pease’s statue could publicly and overtly convey a narrative with a lifespan beyond the celebrations about the importance of Joseph and a range of aspects about his life and career. Simultaneously, it connected elements of his identity and his family’s consistent dominant position in North Eastern railways to the S&DR and its anniversary by staging the unveiling in line with the celebrations.

The banquet on 27 September was held solely for invited guests and, at specified times, the press. The banqueting space had a range of decorations linking to the history of the S&DR and the ‘marked progress’ of the railways up to 1875.[14] The head tables on each side of the banquet marquee were decorated with confectionary representations of Locomotion No. 1, ‘with all its feeble prophecies of the growth and the future greatness of engineering skill’, alongside a modern engine ‘with its almost perfect workmanship’ (Jeans, 1875b).[15] Further, a cornice supporting canopy boards behind the chairman and vice-chairman’s table was decorated with images of Locomotion No. 1 and ‘its modern compeer’, with dates 1825 and 1875 placed above each engine respectively (Jeans, 1875b).[16]

In this commemoratively-dressed space, the banquet speeches and toasts allowed the organisers to highlight the importance of both the S&DR and the NER stemming from the origins of the railway system to their select political and industrial guests. Along with a lengthy breakdown of the financial success of the original railway and improvements in rail technology, Henry Pease spent a large portion of his banquet speech defending the claim that the S&DR was the first steam-powered passenger railway in the country.[17] Further, in line with the narrative of the exhibition and the decorations in the marquee, Pease lauded the ‘wonderful industrial changes brought about by the system’, how it benefitted the ‘domestic requirements’ of the region, and concluded with how the S&DR was the beginning of wide-scale national transportation for goods and passengers.[18] The rhetoric used was not without further criticism from West, who suggested that, once again, the speeches and toasts made it unclear as to what or who the assembled guests were celebrating:

Was it the real ‘Pioneers’ notably Edward Pease the shrewd Promoter, George Stephenson the shrewd Engineer & Francis Mewburn their equally astute solicitor or was it to include the one whose statue was that day unveiled & hence all the notable men of his era with whom the present generation in Darlington are far most familiar. The Promoters certainly had no clear lines on this important point, & displayed in their selection of names either lamentable ignorance or detestable partiality (West, 1876, p 50).

The central narrative of the jubilee was therefore not easily understood from the content of the speeches at the banquet. However, thinking about this in line with the guests present and following on from the statue unveiling, this event was an opportunity to highlight the success of the NER using the history of the S&DR to demonstrate its progressive development and financial successes.

Commemorative literature was a significant way to leave a lasting memorial of the history that was being celebrated as well as the celebratory event itself. Books could carry the narrative about the events and the history of the S&DR more so than the symbolic or physical elements of the celebrations. A book produced by the journalist, J S Jeans, entitled History of the Stockton & Darlington Railway: Jubilee Memorial of the Railway System, was created specifically to be presented as a gift to the invited guests at the banquet (Jeans, 1875a). It documented the history of the railways up to 1875, with a focus on the North-Eastern railway system. At the close of the book’s introduction, Jeans drew together the important themes of the jubilee:

the past and the present are now sufficiently within range to enable us to judge of the future, and to appreciate, more justly than could possibly have been done at any previous date, the momentous and far-reaching results of the work that was consummated by the pioneers of the first public railway on the 27th September 1825 (Jeans, 1875b).

The book therefore provided a history of the S&DR but also aimed to show how the hard work of notable men enabled this to become, as stated in Pease’s speech, the ‘first’ public railway in the country, and reminded the readers of the progress that had been occurred in the years following its conception.

Despite the ‘muddled’ narratives carried across the various commemorative components that made it difficult to properly understand what the celebrations were trying to achieve, when drawing the components together as interlocking parts of an overall event, the central themes were used to legitimise and demonstrate the prowess and success of the NER to their carefully selected audiences. There was a respect for and celebration of men who had been instrumental in creating and sustaining the railways in the North East, with a particular focus on the Pease family who were still very influential in the town; a demonstration of progress between 1825 and 1875; a defence of the S&DR as the first public railway; and more generally a celebration of the success of North Eastern railways since the S&DR that, according the commemorative narrative, continued to be financially profitable and benefit the local areas they served.

Centenary, 1925

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221708/004The organising committee of the ‘official’ centenary was headed by the management of the LNER, with the Chairman of the company and Conservative MP William Whitelaw as the chair, and the Pease family still being represented 50 years later by Arthur Pease.[19] Planning began in 1923, with one committee to organise an exhibition in Darlington and another to manage local arrangements with organisational input from the regional authorities of Darlington, Stockton and Yarm.[20] In line with the former jubilee celebrations, Darlington civic representatives were keen on preserving the narrative of the town’s importance in the history of the S&DR and industry more broadly.[21] However, with the Darlington civic representatives holding less control over LNER’s plans for the centenary than in 1875, the geographical range was extended beyond the town to include places that had a strong connection to the line. Further, more notably than during the jubilee, LNER organised a series of events that would accommodate both their invited guests and the public, and the local authorities of Stockton and Darlington organised events in tandem with the official ones to celebrate their local communities as much as the railway’s centenary.

There were four key themes that would shape the central narrative of the LNER-organised events. First, by the 1925 celebrations, the passenger use of railways was gradually in decline (Simmons, 1975, p 72). Reasons for this included concerns over their safety, supposed poor treatment of their employees, problems with the height of rates, and strong competition from the automobile industry (British Rail, 1976). As such, the ‘official’ celebrations were used to project a forward-facing outlook on the railways by showing that they had a future, represented modernity, and that they were an equal contender in the battle for passenger transportation both in Britain and internationally (British Rail, 1976). Second, which had been set up during the jubilee celebrations, was the prominence of Britain in the history of the railways and as such solidifying the S&DR as an important ‘first’. Third, arranging the attendance of the Duke and Duchess of York to perform official duties for the centenary suggests the committee assumed more national interest in the importance of the celebrations.[22] Finally, the centenary had to function as both a celebration of British railways and its impact more globally as they had to accommodate their international guests attending the International Railway Congress (IRC) from 22 June to 4 July 1925.[23]

Though committee discussions showed they considered holding the centenary celebrations in September, it was decided that they should be held in June–July to work in conjunction with the IRC, which was held in England that year.[24] The IRC Association was established in 1885 during the jubilee celebrations of Belgian railways that year (Journal of the Institution of Railway Engineers, 1925; Railway Age, 1925). These celebrations were attended by delegates from 19 countries and representing 131 different railways (Journal of the Institution of Railway Engineers, 1925, p 482; Railway Age, 1925, p 1431). It was reported that this initial gathering of international railway companies was so successful that the delegates agreed to form an association to hold regular meetings at four-year intervals (Journal of the Institution of Railway Engineers, 1925). The IRC aimed to ‘encourage the development of railway transport by intensifying exchanges of experience between its members’ around the world (de Fontgalland, 1984, p 198). The venue and date of the IRC was changed from Madrid, 1927 to London, 1925, as it was decided that the importance of the S&DR centenary ‘justified a special gathering’ of the Association (The Times, 1925). Specific events were arranged to accommodate the congress delegates on the final day of the anniversary celebrations and a strong international thread was woven into the core commemorative narratives.

A range of components were used to project the core narratives of the centenary celebrations – that the LNER and British railways more broadly were forward-facing, had a place in the future, represented modernity, and were an equal contender in the battle for passenger transportation both in Britain and internationally. LNER-organised events were held from 1–3 July in both Stockton and Darlington (Table 2), with the locally organised events held on the second and third days.[25] Some of the commemorative components mimicked those used during the jubilee while adding elements that made tactical use of the centenary to LNER’s advantage. More effectively than during the jubilee, the organisers successfully solidified their key narratives over a wider variety of components, including events, exhibitions and the use of historic and new ephemeral and physical objects. Analysing a selection of these components will demonstrate the efficacy of the commemorative narratives and their vehicles of delivery.

Table 2

| Date | Events |

| 1 July | The opening of an exhibition of historic relics of the railways displayed at the Faverdale Wagon Works, Darlington. |

| 2 July | A procession of historic and modern locomotives along the former S&DR line. |

| Luncheon for invited guests at Stockton Borough Hall for the Duke and Duchess of York and invited guests. | |

| The unveiling of a commemorative tablet in Stockton. | |

| The opening of the exhibition at the Faverdale Wagon Works to general visitors. | |

| A banquet for invited guests at the Faverdale Wagon Works. | |

| 3 July | A luncheon and for the delegates of the IRC at the Faverdale Wagon Works. |

LNER programme of events for S&DR centenary, 1925 (London and North Eastern Railway, 1925, p 5; Borough of Stockton-on-Tees, 1925)

Stylistically taking much from the design of the jubilee display, on 1 July an ‘exhibition of items of historical interest in the development of Railways’ at the new Faverdale Wagon Works in Darlington was ceremonially opened by the Duke and Duchess of York (London and North Eastern Railway, 1925).[26] The event was attended by invited guests and opened for public viewing the following day. The content of the exhibition was provided by all the Big Four railway companies and the Metropolitan Railway Company. As in 1875, and in tandem with prints, models, documents and signalling apparatus, the engines displayed exhibited a linear narrative of how the industry had developed since 1825 (London and North Eastern Railway Company, 1925). Further, the use of the Wagon Works for both the exhibition and the two events (Table 2) appears to have been deliberate to showcase the new facility to the wider public and LNER’s economically and politically important guests.

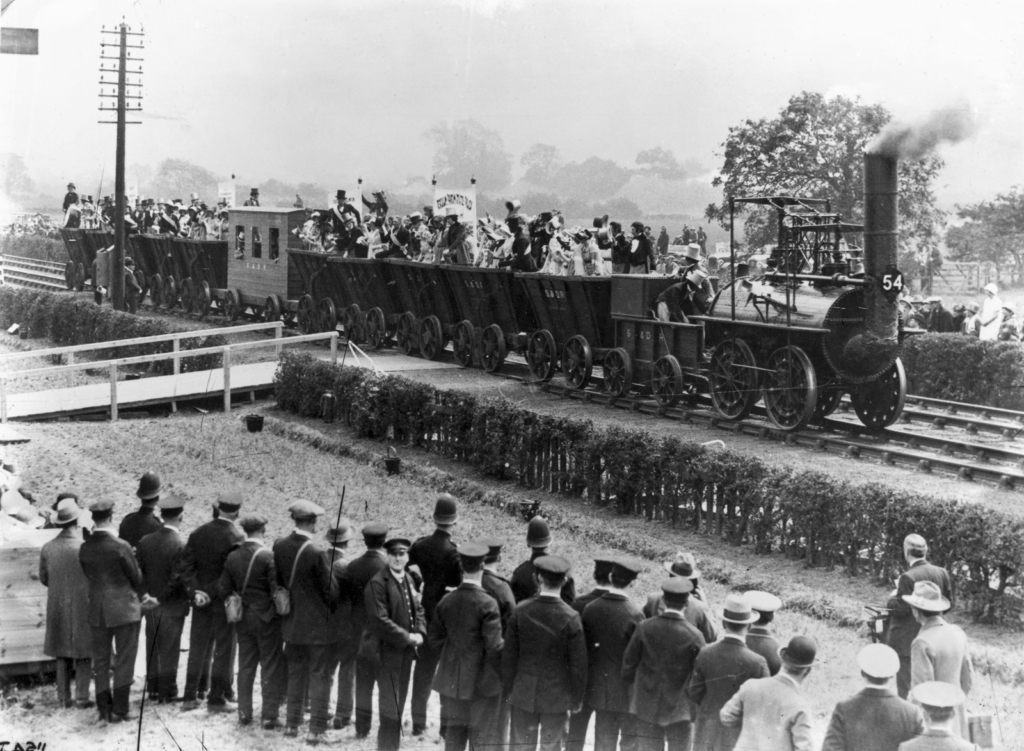

In addition to the static display, and deploying a new component not used during the jubilee, on 2 July LNER staged a moving procession of old and modern locomotives and rolling stock along the original S&DR line.[27] Available to view by a range of spectators, a grandstand was erected, paid plank seating was provided for members of the general public, a section of the fields nearby was reserved for the Car Club (Figure 4), and the public were charged 6d. to view the cavalcade from the fields in Yarm next to the line.[28] The programme described the procession as ‘thoroughly representative of a century of progress in the art of providing comfortable travel’.[29] Like the exhibition, it comprised of engines that had served the whole British railway network, past and present. Five engines still serving the national rail network from all the Big Four Companies (GWR represented by two engines) concluded the cavalcade, with LNER’s Pacific type City of Newcastle drawing the Flying Scotsman as the last of these modern engines (London and North Eastern Railway, 1925, p 16). To clearly show the progress of the technology, LNER engines were immediately followed by the standout historical spectacle of the event – the original Locomotion No. 1 hauling a replica train (Figure 5) (London and North Eastern Railway, 1925, p 16).

Supporting a narrative of national and international technological progress, a series of ‘tableaux’ were staged in the middle of the cavalcade of engines ‘to show the evolution of the wheel in transport’, with a banner above each saying how long since the present day each of these scenes were set (Figure 6) (London and North Eastern Railway, 1925).[30] It commenced with an ‘allegorical tableau showing early astrologers alongside Modern Engineering Practice’ (London and North Eastern Railway, 1925, p 10). The subsequent tableaux included ‘Earlyman’ and the wheel, the Pharaohs drawn along on wheeled platforms by slaves, the eighteenth century where ‘fashion discarded the wheel’, George Stephenson explaining a model of the steam engine Rocket in Darlington, and finally the modern use of railways (London and North Eastern Railway, 1925, p 10). The programme described the final tableau as:

the world-wide use of Railways. From the few miles of permanent way which united Stockton and over Darlington and which the first train ran in 1825 have evolved the steel ribbons which to-day are traversed by millions of wheels, tying every corner of the Land to the Empire’s Capital (London and North Eastern Railway, 1925, p 10).

By processing their most modern technology alongside their oldest engines, supported by this the tableaux, the centenary cavalcade provided a visual experience that expressed the narrative of technological progress, and economic and political power. British railways were situated in a linear narrative of industrial development, this time one that extensively predated that of the early nineteenth-century developments of the industry and geographically extended much further to signal their imperial reach.

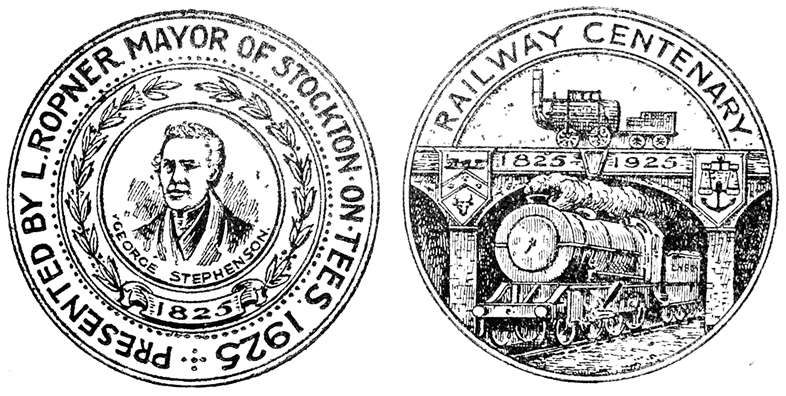

As in 1875, commemorative objects designed specifically for the celebrations were important components of the celebrations. The imagery of the final two engines in the cavalcade finale was echoed in a commemorative centenary medallion (Figure 7).[31] Designed by Gilbert Bayes, the imagery on the medallion retold the story of the long history of progress seen in the steam cavalcade (Attwood, 1992, pp 148–9; The Financial Times, 1925, p 8).[32] On the obverse side, the coin shows Vulcan, the Greek god of metalwork, holding Locomotion No. 1 with an LNER Pacific type engine above and the phrase ‘FIRST IN THE WORLD’. The addition of Vulcan can be read as a continuation of the narrative of the ancient connections of the railway seen in the first tableau. On the reverse, the busts of George Stephenson and Edward Pease are situated in between the civic crests of Stockton and Darlington with the phrase ‘STOCKTON AND DARLINGTON RAILWAY – INCLUDED IN LONDON & NORTH EASTERN RAILWAY 1825–1925’.

The image of Stephenson as an important figure in the history of the railways was carried forward from 1875, but Edward Pease replaced that of his son, Joseph. Edward Pease was economically influential in the establishment of the S&DR, and therefore his image alongside Stephenson suggests that technological development and business acumen were important features of the celebrations. The medallion alone drew together several elements of LNER’s commemorative narrative and was intended to survive and be viewed well beyond 1925, though a more ephemeral record of the centenary, a series of souvenir napkins (most likely to be used at the dining events at the grandstand at the cavalcade) underscored key elements of the S&DR and the centenary (Figure 8).[33] All were intricately bordered, had text setting out all or parts of the programme of events for the centenary, and images that represented important elements of S&DR history and the centenary celebrations. The imagery highlighted the progress of the travel prior to the development of the railways, the key contributors to the success of the S&DR, Edward Pease and George Stephenson, and the importance of the centenary nationally using images of the Duke and Duchess of York and a timetable of events they would be attending. Though they may not have been intended to have lengthy lifespan due to the fragility of their materials, the napkins tied together central narratives of the centenary for those attending the celebrations and ephemerally memorialised the anniversary.

The narrative of the S&DR and its international impact were intertwined with elements of that year’s IRC Association gathering. The organisers included commemorative components in the exhibition specifically for this international audience. This can be seen, for example, in a banner hung in the Wagon Works exhibition (Figure 9).[34] It illustrated the busts of Edward Pease and George Stephenson above a short paragraph in English stating that Locomotion No. 1, built by Stephenson, was the first train to be used on a public railway, and below an image of Locomotion No. 1 the same paragraph was translated into French and German. Making the narrative accessible for their international guests and again featuring both Pease and Stephenson, this banner supported core narrative threads by combining the themes of business and technological acumen alongside the international development this railway had encouraged. Additionally, as seen in the cavalcade tableaux, the language of the speeches at the luncheon highlighted the interconnection between the British Empire’s railways and the S&DR. For example, at the beginning of the banquet, William Whitelaw is quoted as saying:

the hope that railways may ever be the handmaidens of your Empire’s prosperity in the centuries to come as they had been in the century just completed (The Northern Whig and Belfast Post, 1925, p 7).

These components demonstrated that the S&DR centenary was therefore tied more directly to their narrative of international progress and to accommodate the IRC delegates.

Reciprocally, gifts were presented by their international guests to the British railways at the luncheon on 3 July that celebrated the S&DR, British railways, the British nation, the IRC, and the progress of the industry globally. For example, the Italian delegation presented ‘the British nation’ with a bronze plaque (Figure 10) paid for by subscription from Italian railwaymen, which first and foremost celebrated the role of George Stephenson – whose portrait is in the centre held by two Italian railwaymen – in the development of the railways (Railway Gazette, 1925).[35] Couched in the language of admiration for Stephenson, the railwaymen of Italy wanted to show gratitude for the political and economic development the S&DR had enabled for their country. Alongside the central celebration of Italy’s railways and Stephenson, Locomotion No. 1 and a British Pacific type engine are represented at the bottom of the plaque with the winged-wheel, the symbol for speed, in between to represent the progress of the railways from 1825–1925 (Figure 11) (Financial Times, 1925, p 2; The Northern Whig and Belfast Post, 1925). Additionally, three ‘scrolls of honour’ with a poem printed on them expressing the role of the S&DR in the development of railways internationally were presented to the railway companies of Britain by Dr Chin Chun Wang on behalf of the Chinese delegates (Figure 12) (Railway Gazette, 1925; North Eastern and Scottish Magazine, 1925). These gifts demonstrate that there was already a level of international knowledge about, and admiration for, the ground-breaking role of the S&DR alongside the people who created and developed it in shaping the development of railways across the world. Further, they tied neatly to the LNER’s well-designed narrative thread of the international influence of British railways.

Looking now to local celebrations, Stockton Council used a combination of similar and modified components from the 1875 jubilee and the parallel LNER-led events. These events were intended to be more inclusive for the local people. This included competitions to decorate the town, sporting events, an exhibition ‘of the Industries of Stockton and the District’ from 1–9 July, and a series of ‘Children’s Teas’ on 3 July for schools across the town. At these Teas, Stockton’s Mayor and Mayoress presented the children with their own centenary medallions (Figure 13) (Borough of Stockton-on-Tees, 1925, pp 19–25). They carried a similar narrative to the LNER medallion, with the bust of Stephenson on the obverse and Locomotion No. 1 alongside a modern engine on the reverse. The town also staged their own static historic tableaux that told the story of key moments in the history of the town. The first seven scenes celebrated elements of their history unrelated to railways, while the final five documented the beginning of the S&DR, from the ‘First public mention of railway project, (1810)’ to the ‘Banquet at Stockton Town Hall’ on 27 September 1825 (Borough of Stockton-on-Tees, 1925, pp 19–25).

Darlington also held its own events, including choral competitions, sporting events for children, and a cricket match between staff from the ‘North Eastern Area, York, and the Great Eastern Cricket Club’.[36] As in Stockton, Darlington held an event for the school children of the area.[37] At this event, Darlington’s own centenary medal, which was presented by the Mayor, William Pease, to the children of the town, represented Locomotion No. 1 on the obverse side and a modern engine on the reverse (Figure 14).[38] Once again, the medals, as portable, lasting memorials, extended the story of the S&DR and the centenary celebrations to a wider audience, and in particular a young audience who could carry this narrative beyond 1925. Further, both Stockton and Darlington held religious ‘thanksgiving services’ on Sunday 5 July celebrating the role of the railways in the area (County Borough of Darlington, 1925, p 90; Stockton-on-Tees Railway Centenary Committee, 1925).[39] Both towns used the anniversary as an opportunity to bring local people together, celebrating their past and present achievements and highlighting their sense of pride and community in connection to this industrial heritage.

These events coalesced local and national histories in their commemorative components that celebrated their towns and what their residents had achieved. Notably, as seen during the jubilee, there was still a clear separation between the corporate-focused events for invited guests and those for lower grades of workers and local communities. It is then through ‘alternative’ commemorative components and events that we find the critiques of how and what was conveyed through the company-led celebrations.

Challenging the official celebrations

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221708/005Conflict over how the past is used for present purposes can occur due to the range of stakeholders, and narratives can be contentious depending on the elements of the past used and the types of participants the anniversaries claim to represent (Frost and Laing, 2013, p 15). Commemoration is ‘inherently complicated and contentious’ (Gobel and Rossell, 2013, p 1) because it is part of forming both our individual and collective identities and our cultural landscape. In this context, because the organisers of the anniversaries were satisfying their own ‘present goals’ (Frost and Laing, 2013, p 9), this created contested interpretations of the past by other stakeholders with different visions of S&DR’s history and the industry in the present. The celebrations led by the railway companies were not seen by all as the best representations of the narratives of the S&DR or the communities who worked for and profited from the railway industry. As examined above, there was a marked separation between official, company elements, and those created for and on occasions managed by local people during both anniversaries. Alternative commemorations and commentaries about the official narratives that recognised the exclusion or marginalisation of certain groups and communities therefore worked to challenge or undermine the primary commemorative narrative or cement their place within it (Ashplant, Dawson and Roper, 2009, p 21). It is important to examine these instances that subverted, challenged or ran tangentially to the commemorative narratives to create a multiplicity of alternative narratives that came into direct conflict with those passed down through the successive companies that claimed ownership of the S&DR in their anniversary celebrations.

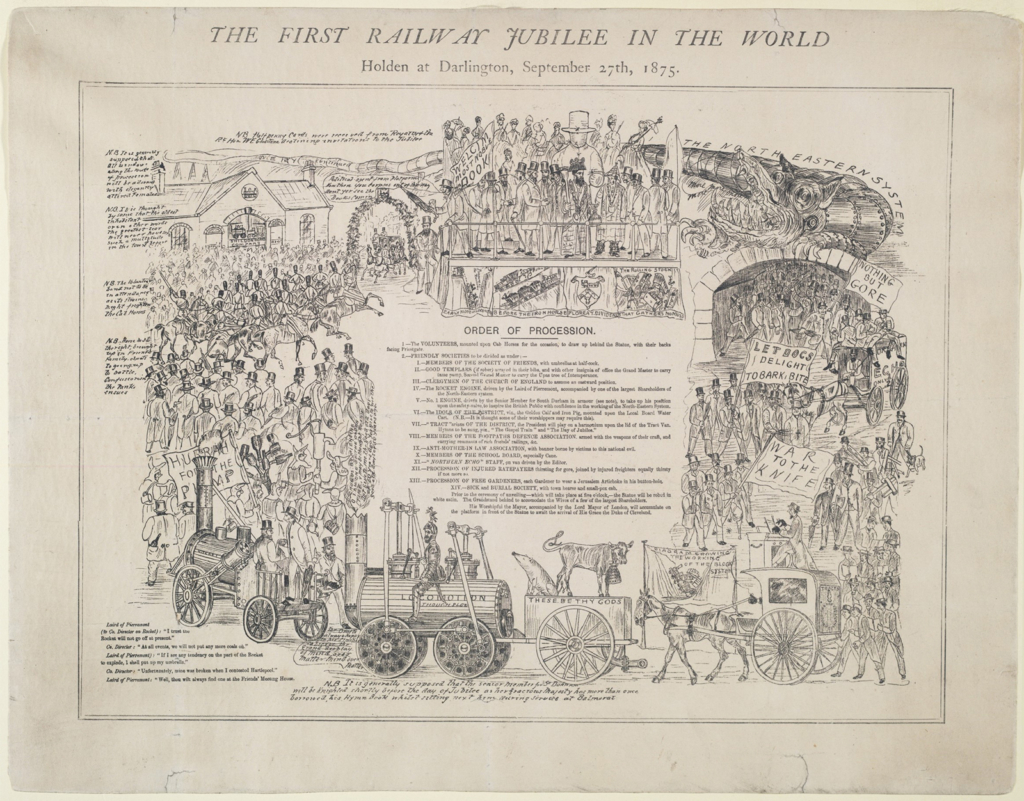

The jubilee celebrations were not uncontested. The nineteenth-century satirical cartoonist Samuel Tuke Richardson was particularly critical of the selective narratives of the jubilee. Two pieces of his work that complement each other were a satirical cartoon illustrating the jubilee (Figure 15) and a book entitled World’s First Railway Jubilee (1876). The cartoon ‘caused a great deal of annoyance to many people besides those who were caricatured’ because it portrayed the NER and the S&DR jubilee in a particularly negative light.[41] There are several images that can be interpreted, but the first of two examples is a small diagram at the bottom of the page entitled ‘DIAGRAM SHOWING THE WORKING OF THE BLOCK SYSTEM’ that illustrated a pile of trains that had crashed, suggesting their block signalling system was inefficient and potentially dangerous. This contravened the jubilee’s positive image of NER’S technologies, and suggests the discontent of others regarding these official, company narratives. The issue of safety was expanded upon in Richardson’s book in a poem and cartoon entitled ‘The Jubilee Jumble’ where, quite drastically, a train taking the Friends (referring to the Quaker owners of the NER) to a Quarterly Meeting had a fault which caused the engine to explode killing all of the passengers as they crossed one the network’s bridges (Richardson, 1876). The reality of the safety issues of the railway system was therefore widely understood, and while the NER tried to enforce a more positive image of the industry using selective narratives conveyed through the jubilee components for the chosen audiences, concerns were being voiced in potentially more impactful, public forums.

A second negative aspect of the NER and the jubilee highlighted by Richardson was illustrated by a large iron figure captioned ‘THE NORTH EASTERN RAILWAY SYSTEM’ with the words ‘more more more’ coming out of its mouth. This figure was a representation of the over-expansion of the NER using the story of the North-Eastern myth of the Lambton Worm, about a small worm from a lake that grew to a gigantic size after consuming and destroying much of Lambton, as a comparison (Fraiser and Surtees, 1832). This was again supported in the book, where Richardson wrote a story comically comparing the building of the S&DR – represented by a worm-like creature that hatched out of a bird’s egg laid on the edge of a stream in the area – to the myth of the Lambton Worm (Richardson, 1876). The story read that while many of the local people wanted to get rid of the animal in its early stages of growth, as it began to develop, it progressively gained support until it expanded ‘stretching between Stockton and Darlington’, and after some years ‘became very grewsome [sic]’ and ‘multiplied until its offspring stretched to all parts of the earth, and until there was not a county in England in which some of them were found’ (Richardson, 1876). In direct connection to the visual narrative of the cartoon and the jubilee celebrations, Richardson wrote:

it was therefore decided to raise a statue to the same of the man who had originally advocated throwing the worm into the canal, and who had made an immense fortune out of the worm, which was appeased by coals poured down its throat in scuttle loads, and the constant cry of that worm was more, more, nor was it particular what it ate, and has frequently been known to swallow up those who have done the most to assist its growth, but have had the misfortune to get within its clutches (Richardson, 1876).

Richardson’s commentaries on the S&DR and NER not only contravened the markedly positive narrative pedalled by the NER, but also challenged their narrow, linear narrative of technological development by providing alternative or parallel accounts of the development of the railway and highlighting a multiplicity of feelings about both the history of the line and how it was celebrated.

A further, very central critique of the jubilee was that though the locals of Darlington were granted a general holiday from 27–29 September and were invited to decorate the town, their involvement in the festivities was side-lined and several of the events of the day were organised solely for invited participants (West, 1876).[42] Issues about this lack of local and worker involvement were sounded out in a satirical piece entitled T’Gurt Railway Jubilee: My Prisence & Harty Approvil, written under the pseudonym of T’Licend Hawker (Hawker, 1875). The article outlined the jubilee celebrations from the perspective of the journalist from the North East of England (Hawker, 1875). In the semi-fictional account, T’Licend Hawker was sent an invitation to the jubilee celebrations (Hawker, 1875). He documented the events of the day and commented on how he felt particularly out of place during the ceremonies as he did not appear to be of the same social standing as the other invited guests. For example, he was questioned for having a first-class ticket when trying to board the train to Darlington and was later chastised for not knowing how to act appropriately at the banquet (Hawker, 1875). This commentary highlighted the notable absence of local people in many of the celebratory components, as well as how these performative events were exclusionary by assuming and employing hierarchical rules of etiquette that these communities were likely not familiar with.

These arguments were again supported by Richardson’s book in two sections entitled ‘The Banquet’ and ‘The Street Banquet’ (Richardson, 1876). The former described the rich refreshments and entertainment for the ‘assembled multitude of eminent philanthropists, who had either made or been connected in some way with the making or development of the North Eastern Railway, solely no doubt with a view to the elevation and advancement of the human race’ (Richardson, 1876). The latter highlighted the contrasting style of the public street event ‘for those who were not sufficiently influential or wealthy enough to partake of the Banquet’, who were served an inadequate supply of tea and Pease Pudding (relating to the prevalence of the Pease family in the official celebrations), ‘the former brewed in the Boiler of No. 1 Engine, while the latter viands were piled upon the tender’ (Richardson, 1876). Though both over-emphasised the version of events, they again signalled the distinct difference in the way invited guests and local people celebrated the jubilee.

Though the centenary celebrations did not receive the same level of criticism as the jubilee, in the same year anniversary celebrations of the S&DR were independently held by railway workers from around the country. This event was important for the workers as the core narrative was seen to better represent the meaning and importance of the railways to them, and was purposefully designed to showcase this community’s involvement rather than bringing in the themes of empire and investment seen in the official celebrations.

Railway staff were more involved as observational participants in the official celebrations than the jubilee, with provisions being made for them to attend certain events. The initiative to include the staff specifically in the celebrations was pushed by the railway unions, who approached the committee to accommodate them appropriately.[43] This included reserving spaces for employees of the LNER to view the cavalcade procession organised by the company.[44] However, the wider community of railway workers did not have the power to influence the organisation of the official centenary events.

This led to the railwaymen holding their own ‘real’ centenary in Manchester on 27 September (the actual anniversary date) the same year at the Belle Vue Hotel (Great Western Railway Magazine, July 1925).[45] The idea to hold this centenary was conceived by a shunter from Edge Hill, Liverpool, and the railway worker-only event sold out its 50,000 tickets to railway workers of all levels and from all companies (The Observer, 1925). The celebrations were held in conjunction with the first crowning of the ‘Railway Queen’ – a young girl selected annually until 1975 from a railway family who officially represented the British workers globally – and included a cavalcade of historic tableaux of the progress of the railway (The Observer, 1925).[46]

The rhetoric suggested that the anniversary was used to demonstrate collaboration between employer and employee (The Times, 1925, p 11). The day was described by the general manager of the LMS, Mr Burgess, in his speech at the event as ‘a very happy omen of the good will and enthusiasm which animated all grades of employees in the country’ (The Times, 1925, p 11). Further, the secretary of the organising committee, Mr H H Neilson, stated that ‘The employees…had met with the heartiest goodwill on approaching their employers’ to arrange these celebrations (The Observer, 1925, p 13).[46]

Neilson stated further that the organisers wanted ‘all grades’ to be:

joined together in the spirit of goodwill. On this day we shall unite to do honour to the memory of George Stephenson and other railway pioneers…, and to the craft that we all serve (The Observer, 1925).

Gillis suggests that since the nineteenth century, commemorations were ‘largely for, but not of, the people’ (Gillis, 1994, p 9). The necessity to hold both an official and a real centenary of the S&DR demonstrates this. By staging their own event, the railwaymen could better represent their role in the history and present shape of the industry (Allen, 1925).

The railway workers used the ‘real’ centenary celebrations as a vehicle to demonstrate the importance of the employees and employers in the development of the railways through practices of their own – namely the ‘Railway Queen’ crowning – as well as similar techniques used by the LNER. Therefore, though the underlying historical reasons for celebrating were the same as the official anniversary, the railway workers used the events to create a democratic narrative about the importance of the railway community as a whole.

Conclusions

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221708/006Commemorations are important ways communities show an interest in their history. They remember and misremember, manipulate and change these narratives, as the past becomes a backdrop for contemporary needs, obsessions and fears. Conveyed through a series of commemorative components, the railway companies strategically used narratives about the progress of the industry built on the history of the S&DR and, particularly through the exhibitions and cavalcades, demonstrated this change over time. The image of the line as the ‘first passenger railway in the world’ was enhanced and cemented through the subsequent large-scale anniversary celebrations. In turn, by celebrating their past, the companies developed a narrative of a long history of technological and economic progress stemming from the S&DR to their chosen audiences. Further, while these events were industry-focused and spoke primarily to an industrial audience using the history of the S&DR, they also projected a narrative about the developments locally, nationally and internationally.

Famous individuals and commemorative objects were significant vehicles in demonstrating this successful progression of the industry while developing and sustaining new identities. For the companies figures like Stephenson and the Pease family, and notable engines, were figureheads that became synonymous with the success of the S&DR, and in turn NER and LNER as they assimilated these images into their own identities. Locomotives and historic items were used as a physical representation of the technological advancement, while new commemorative objects like statues and memorabilia could more overtly deliver this narrative. By employing similar commemorative practices in both celebrations, such as using historic and current locomotive engines, they also created new commemorative cultures not only through their conjoined history, but how they came to remember it.

The centenary organisers more successfully cemented their core narratives which made the purpose of the centenary clearer than in 1875. The number of components used to convey the central narratives of the centenary surpassed those of the previous anniversary, both in terms of the length of time over which they were held and range of styles they utilised. The material culture of the centenary celebrations, in conjunction with the narrative of the temporary events, was used by LNER to construct narratives about the economic and political power of the company using the history of the S&DR, while this time extending the narrative of technological progress into an ancient past. Furthermore, the archival and material records demonstrate that these events were understood on local, national and international levels and that they featured several interrelated commemorative components from these different vectors. LNER used symbols of their ancient and historic past alongside modern representations of their company to develop a linear narrative of the power and importance of British railways with the company at its centre.

Crucially, these narratives were not uncontested. An array of other communities ranging from groups of workers to local town councils highlighted the selective nature of commemorative narratives and the communities the celebrations aimed to represent. As counternarratives to the jubilee, satirical literature in 1875 mocked the commemorative styles used by the organisers, and in doing so emphasised the narrowness and ambiguity of their central narratives, the realities of the present railway industry, and the arms-length distance local people were held at in events that were centred on their localities. As an alternative to the official narrative, however, the workers in 1925 used the centenary as an opportunity to strengthen community bonds by overlaying their own celebratory traditions on a narrative of the history of the railways and their part in that progression.

The S&DR anniversaries have been used as a platform to develop narratives about, and of, the present using the prestige of the past as a means of creating or supporting an identity of those carrying out the commemorative practices. For the companies, this enhanced their present economic and political successful image, and suggested a continuation of the industry in Britain into the future both nationally and internationally; and for the railway workers, they showed pride in their peers, companies and craft.

Acknowledgements

Sincere thanks to Andrew Stove (Friends of the Stockton & Darlington Railway) and Neil MacKay (Chairman of the North Eastern Railway Association) for the use of archives and images from their personal collections for this paper.

Primary material

Andrew Stove Private Collection

‘27th September 1875 – Envelope containing Henry Pease’s Hand-written speech (15 pages) and notes for the Jubilee Banquet’

County Borough of Darlington, 1925, Railway Centenary Celebrations. Programme of Variety Entertainments (Darlington: W. H. and Sons, Printers)

‘North Eastern Railway. Celebration at Darlington of the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Opening of the Stockton and Darlington Railway, September 27th and 28th, 1875. General Programme’

‘Plan of the Town of Darlington, 1875’

Poster, ‘H. F. Pease. Borough of Darlington. Railway Jubilee. “General Holiday”’

Poster, ‘Railway Jubilee. Grand Tea Meeting’

Poster, ‘The Railway Jubilee. “General Holiday”’

‘Souvenir Napkin, S&DR Centenary, 1925, Depicting the Duke and Duchess of York’

‘Souvenir Napkin, S&DR Centenary, 1925, with Photograph of Locomotion No. 1’

‘Souvenir Napkin, S&DR Centenary, 1925, Depicting Edward Pease, George Stephenson, and Locomotion No. 1’

‘Stockton-on-Tees Borough Council and Amenities Department, Stockton 150 Committee, Souvenir Programme’

‘The Railway Centenary. United Service of Thanksgiving to be Held at Darlington Railway Station, at 2-15 p.m., on Sunday, 5th July, 1925. Order of Service and Hymns’

West, Theodore, 1876, ‘The Railway “Do” at Darlington’

National Railway Museum

NRM – Coins and Medals, 1960–76, ‘Bronze Medal Struck to Commemorate the Centenary of the Stockton & Darlington Railway’

—, 1986-8015, ‘Commemorative Medallion, Railway Centenary’

NRM – Documents, 2004-7163, ‘Commemorative Paper Napkin Printed with Programme and Souvenir of the Railway Centenary event Wednesday July 1st, and Thursday July 2nd, 1925. Illustrated with Drawing of Travelling by Stagecoach and Horses and Surrounded by Yellow and Green Floral Motif’

—, 2007-7241, ‘North-Eastern Railway. Fiftieth Anniversary of the Opening of the Stockton and Darlington Railway. Programme of Fireworks’

—, 2008-7606, ‘The Railway Centenary Opened by the Duke of York’

—, 2008-7612, ‘London and North Eastern Railway Committee Minutes Regarding the Stockton and Darlington Centenary Celebrations, 1925’

NRM – Pictorial Collection (Railway), 1977-7544, ‘Accompanying Letter by Malcolm Spence Written 1911 to The First Railway Jubilee in the World (Darlington)’

—, 1977-7544, ‘The First Railway Jubilee in the World (Darlington)’

NRM – Photographic Collection, 1997-7236, ‘An Album of 140 Silver Gelatine Prints, Featuring the Centenary Celebrations of the Stockton & Darlington Railway’

—, 1997-7245, ‘Collection of Photographic Prints B&W, ex-BR Headquarters, York’

—, Misc/111, ‘Catalogue of Engines Exhibited, Complete with Photographs and Locomotive Histories, 1875’

NRM – Miscellanea & Curiosities, 1925-733, ‘Bronze Plaque, Commemorative of the Railway Centenary Celebrations at Darlington, 1925’

North Eastern Railway Association

Armstrong, J W, Armstrong Railway Photographic Trust, ‘S&DR 1925 Celebrations, Urlay Nook’

The National Archives

RAIL 390/14, ‘Minutes of meetings of special committee including: Joint Areas Hotels London Suburban Traffic Jt. Locomotive and Traffic Superannuation Funds L.N.E.R. Housing Trust Special Committee of Directors (Stockton & Darlington Centenary) Welfare Expenditure on Capital Account Post-War Policy’

RAIL 390/1602, ‘Stockton and Darlington Centenary Celebrations’

RAIL 393/336, ‘Commemoration of Railway Centenary. Guard Book Compiled by Company’

RAIL 667/165, ‘Minutes of Meeting of Committee to Celebrate the Railway Jubilee’

RAIL 667/459, ‘Jubilee: Admission Tickets, Guide Book, Concert Programmes, Seating Plan etc’

ZSPC 11/416/11: London and North Eastern Railway Company, 1925, ‘Catalogue of the Collection of Railway Relics and Modern Stock at Faverdale Darlington in Connection with the Railway Centenary Celebrations, July 1925’ (York: BBN Johnson & Co. Ltd. Printers)

Magazines and newspapers

Cecil J Allen, November 1925, ‘Celebrating the Real Railway Centenary’. Great Eastern Magazine, Vol 15. no 179, p 185

Financial Times, 4 July 1925, ‘Italy’s Tribute to British Genius’, p 2

Great Western Railway Magazine, July 1925, Vol. 37 no 7, p 255

Joint Stock Companies’ Journal, 2 October 1875, ‘The Stockton and Darlington Festival’, pp 650–51

Journal of the Institution of Railway Engineers, September-December 1925, ‘The International Railway Congress and the Railway Centenary’, Vol. 15 no 72, pp 482–488

Leeds Mercury, 28 September 1875, ‘The Railway Jubilee’, p 5

North Eastern and Scottish Magazine, August 1925, ‘Visit of the International Railway Congress’, Vol. 15 no 176, p 235

Northern Echo, 3 February 1925, ‘Railway Centenary Supplement, 1825-1925 – Opening of the Stockton & Darlington Railway’, p 21

Railway Age, 1925, ‘Railway Congress of Other Days’, Vol. 78 no 28, p 1431

Railway Gazette, 10 July 1925, ‘Italian Tribute to the British Nation’, p 98

Saturday Review of Politics, Literature, Science and Art, 2 October 1875, ‘The Railway Jubilee’, p 417

—, 10 July 1925, ‘Visit of International Railway Congress’, pp 89–91

The Daily Gazette, 28 September 1875, ‘The Railway Jubilee’, p 3

The Financial Times, 26 June 1925, ‘Railway Centenary Medal’, p 8

The Northern Whig and Belfast Post, 4 July 1925, ‘Romance of the Locomotive’, p 7

The Observer, 27 September 1925, ‘The Railway Centenary’, p 13

The Railway Times, 2 October 1875, ‘The Railway Jubilee’, pp 948–949

The Times, 20 June 1925, ‘International Railway Congress’, p 11

—, 28 September 1925, ‘Railway Pageant. Centenary Display at Manchester. “Rocket” and Modern Models’, p 11

The York Herald, 28 September 1875, ‘The Railway Jubilee’, pp 2–3

Websites

Historic England, ‘Statue of Joseph Pease’, Listing, https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1322930 (accessed 20 December 2019)

Tees Valley Combined Authority, ‘Stockton and Darlington Railway Heritage Programme’, Culture & Tourism, https://teesvalley-ca.gov.uk/culture-tourism/stockton-and-darlington-railway-heritage-action-zone/ (15 September 2021)