From the White Man’s Grave to the White Man’s Home? Experiencing ‘Tropical Africa’ at the 1924–25 British Empire Exhibition

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191101

Abstract

The 1924–25 British Empire Exhibition was the largest colonial exposition in British history. Twenty-seven million people explored its 238-acre grounds, gazed at its displays, and marvelled at its architectural wonders. While exhibits ranged from a series of so-called “native villages”, to a spectacle of tropical medicine, the official intent was consistent – to promote the development of a more self-sufficient Empire. The exploitation of “underdeveloped” African Crown Colonies was considered important in securing this vision. Eschewing the image of “Diseased Africa”, curators sought to encourage temporary settlement and investment by suggesting that medicine had transformed tropical Africa into a land of infinite wealth for the intrepid capitalist. In contrast to many analyses of World’s Fairs, which have focused on catalogues and official materials at the expense of visitor’s narratives, I uncover the tensions between curatorial intention and visitors” experiences. Through an analysis of divergent responses from science communicators and lay-publics, I argue that the curators” vision of “Brightest Africa” was sometimes received, sometimes contested, misinterpreted, or lost in translation. This was because the fair was more than a series of exhibits: it was a miniature city, populated by living displayed peoples, which prompted concerns about disease, sanitation, and racial comingling. While catalogues and captions to the displays sought to pacify the White Man’s Grave, the curators misjudged the effect of the sensorial experience of the exhibition, which often suggested the opposite. Its sights, smells, and sensations conformed to a stereotype of tropical Africa as a deadly place, rather than a “white man’s home”.[1]

Keywords

colonial exposition, colonialism, exhibition, international exposition, propaganda, science communication, tropical medicine, World's Fair

“A Family Party of the British Empire”: broader aims of the British Empire Exhibition

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191101/002[2] The British Empire Exhibition of 1924–25 at Wembley Park (henceforth BEE) was an expression of a triumphant vision of imperial utopia. It was Britain’s first “Great Exhibition” in thirteen years, mounted against a backdrop of the ravages of the First World War, and the shock of Spanish flu. It took place over two seasons, from April to October in 1924, and May to October in 1925. The BEE was one in a lineage of “Great Exhibitions” in the UK, “World’s Fairs” in America, or “Expositions Universelles” in France. Beginning with the London Great Exhibition of 1851, which sought to display the arts and industries of the world in a single site, these exhibitions were popular in the West and Japan, as well as in African and Asian colonies from 1851–1951 (Geppert, 2010, pp 1–8 ; Hoffenberg, 2001, pp 1–30). Like those before it, the BEE was a spectacular display of the people, products and cultures of the British Empire across a series of twenty-four museum-cum-arcade buildings called pavilions. Its distinction was in its status as a ‘colonial exposition’ – a sub-genre of the World’s Fair, popular amongst imperial powers, in which only colonies were invited to participate.

Exhibits were diverse, yet the official intent was largely unified: to increase inter-imperial trade and to promote the development of a more self-sufficient empire (British Empire Exhibition Official Guide, 1924). Its politician organisers, distrustful of European allies and rivals in the aftermath of the First World War, sought to direct increased attention towards its “great, underdeveloped estate” and, in doing so, reduce the need for European trade.[3] It also wished to assert economic dominance in the face of increasing threats from the USA and Japan.[4] The colonies were considered essential in pursuing this goal, but were underfunded, and under-settled. The BEE provided an ideal stage upon which to present their natural and mineral wealth, employment opportunities, climate, or lifestyle.

Curators of the African sections sought to steer public attention away from the gloomy but prevailing idea of the Dark Continent towards a more optimistic vision of ‘Brightest Africa’. At the BEE, tropical Africa was not depicted as a region of savagery, death and disease, but a vibrant, exotic culture, and a land of infinite wealth for the intrepid British capitalist. Such depictions were aligned to the broader goals of promoting the development of resource colonies like the Gold Coast. The enduring prevalence of ideas of the White Man’s Grave – implying that Europeans were racially incapable of surviving in tropical Africa – needed to be challenged, as these would have been a deterrent to even the most fearless industrialist.[5]

The exhibition also arrived in a time of growing nationalism, pan-Africanism, and anti-imperial sentiments in Africa and the USA, with intellectuals like Marcus Garvey advocating the end of European colonialism and African leadership in Africa (Stephen 2013, p 123; Wintz 2015, pp 1–18). In many ways, the African exhibits can be read as a counter narrative to such pan-Africanism. By challenging the concept of White Man’s Grave, curators attempted to suggest that Britain had rendered its African colonies healthy and productive, and their inhabitants disciplined, cooperative, and eager to work. How the tropical African exhibits attempted to pacify fears of the White Man’s Grave, and how various visitors engaged with them, is the subject of the remainder of this paper.

Reading visitors’ experiences: negotiating curatorial intention and sensorial information

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191101/003Histories of World’s Fairs have primarily been written from a top-down curatorial perspective, which describes and unpacks the ideological function of the displays from the perspective of organisers (Munro, 2010, pp 84, 89–90; Rydell, 2006, pp 145–6). They have served as evidence for the European gaze, racial theory, the construction of national identities, imperial culture, and Foucauldian disciplinary society. As early as the 1930s, Benjamin (2002, pp 7–8) considered them to be shining examples of the cultural logic of the twentieth-century, which shaped public understandings of the world itself, and commodity fetishism. They were also foundational to both metropolitan and colonial national identities (MacKenzie, 1984, pp 2, 10, 97–9).[6] Critical to the construction of such identities was the representation of the colonised – often in anthropological “native villages”. These “villages”, which put groups of living peoples on display, sought to offer a slice of “native life”, giving Western publics a voyeuristic glimpse into exotic cultures, without needing to risk the putative horrors of encountering them in situ (Corbey, 1993, pp 338–345). A plethora of historians have argued that such displays played a role in the development of racial theories, and justified colonial expansion by depicting so-called natives as barbaric.[7]

Exhibitions, the argument goes, did not only order and discipline the “other”, but were also technologies of Foucauldian state power, which produced audiences with docile bodies and “improved” the taste and aspirations of the European and North American working classes. Through hierarchical displays of culture, rules prohibiting the touching of artefacts, architectural designs encouraging an orderly crowd, and the presence of police in the form of security guards, exhibitions helped produce a disciplined working class. Likewise, the spectacle of the fair encouraged self-surveillance – the crowd was a fundamental part of the experience. Everyone was on display to everyone else. Such “docile bodies” were susceptible to the ideological content on display, and thus the working class learned to relate to the world in terms of the bourgeois European gaze (Bennett, 1995, pp 55–88).

By-and-large, these studies of World’s Fairs are informed by an assumption that fairs were significant cultural events, containing ideologically influential content. Such arguments presuppose a marriage of curatorial intent and visitor reception because they focus primarily on official sources (written documents, catalogues, reports) at the expense of alternative visitors” narratives. Official materials are saturated in institutional propaganda, usually declare exhibits successful, and reduce the visitors” experience to attendance figures. Yet, exhibitions are not necessarily metonyms of the state (Longair, 2012, p 5), and the intentions of curators do not always translate into practice (MacKenzie, 2010, pp 276–7). Even the process of curating a single exhibition is the result of multiple perspectives, rather than the unified state hegemony presented by the catalogue.

Recent work in the history of expositions and museums has started to move away from this bias towards curatorial intentions, and has begun to expand our understanding of the archive of the fair. Scholars have examined the experiences of visitors and performers (Niquette and Buxton, 1997; Marthur, 2000; Parezo and Fowler, 2007; Qureshi, 2011), debates and counterpropaganda movements stimulated by expositions (Hughes, 2006; Geppert, 2010; Britton, 2010; Stephen, 2013), tried to recreate the “layout of the fair” and its pavilions in book form (Hollengreen, et al, 2014, p 6), and viewed fairs as miniature cities with real urban problems (Brown, 2009). This essay adds to such literature by proposing three interventions.

Firstly, I assert the necessity of critical analysis of the official archive of the fair (planning documents, guidebooks, catalogues, promotional materials) by exposing its internal contradictions and its limits as a source of information. I show here how visitors cannot be treated as blank slates, as they arrive armed with prior knowledge and expectations, which comes into negotiation with the displayed material.

Secondly, I argue the necessity of exploring a variety of potential visitors” experiences within a single fair. I demonstrate how different kinds of visitors, participants and organisers engaged somatically, intellectually and sensorially with displayed material, and how this shaped their interpretations thereof. Here, I have departed from treating fairs as if they were merely books – repositories of textual and discursive information – and sought evidence of the immersive, spatial and somatic experience of navigating the fairgrounds. The history of the senses can provide pointers here. Examining textual, material and visual traces of the senses, and how these were experienced in different historical contexts, is critical in understanding how perceptions of societies were formulated.[8] Such evidence is important in the case of historical exhibitions, as sensory material is not necessarily aligned with exhibition texts, and can often produce contrary or other understandings. As Classen and Howes argue, “artefacts body forth specific “ways of sensing” and they must be approached through the senses, rather than as “texts” to be read or mere visual “signs” to be decoded” (2006, p 200). Analyses of the senses are also vital in understanding how colonial and indigenous categories are constructed in the first place (Edwards, et al, 2006, p 3). These, as Stoler argues were commonly “generated viscerally, out of responses of desire or disgust that could mutate in different kinds of social relations” (Stoler, 1995, paraphrased in (Edwards, et al, 2006, p 3).

Evidence of the sensorial can be difficult to find, as it is almost never explicitly recorded. Yet this information does survive in fragments across print media, ephemera, photography, rare personal accounts and film. In these media, compliments, comments, critiques and anecdotes about the experience of visiting the fair allow historians to reconstruct how various visitors responded to the displayed material. This enables a reading of the visual archive of the fair outside of the intentions of its curators.

Thirdly, I do not treat each exhibit within each pavilion as a distinct and contained curatorial experience. Instead, I show how visitors formed their own narratives of the fair as they wandered between sometimes conflicted different curatorial zones. Such accounts often explicitly contradicted and undermined curatorial intentions.

Ultimately, I assert that we need to recognise that fairs were spectacular experiences in which the sensorial could escape, contradict and sometimes challenge the expression of national identities, disciplinary society and commodity fetishism. Visitors did not always perceive a picture of a carefully curated world, but often a collage of various sights, smells and sensations. As many scholars have argued, objects and images on display are not automatically tied to curatorial intentions, but seem to return our gaze – they have agency to acquire alternative meanings within their historical or cultural contexts (Elkins, 1997, pp 72–3, 86–89; Sontag, 2003, pp 9, 35). Perceptions of objects, images and peoples need to be seen as products of an “education of the senses within a particular sensory milieu” (Edwards, et al, 2006, p 21). Medical photographs in contemporary museums, for example, often resist exhibition narratives because of their intimate and private social connotations, as well as their shock-value. Tying such photographs to a controlled reading can thus be difficult (te Hennepe, 2016, online). Histories of World’s Fairs need to be sensitive to the range of discourses surrounding displayed objects that can exist outside the confines of curatorial intent.

To pose these arguments, I examine representations of tropical Africa and how visitors engaged with these at the BEE by focusing on two separate exhibits: the West African Walled City, and Tropical Health: the campaign against tropical disease in both human and plant life.

From Darkest to Brightest Africa: tropical Africa at the BEE

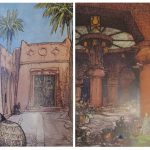

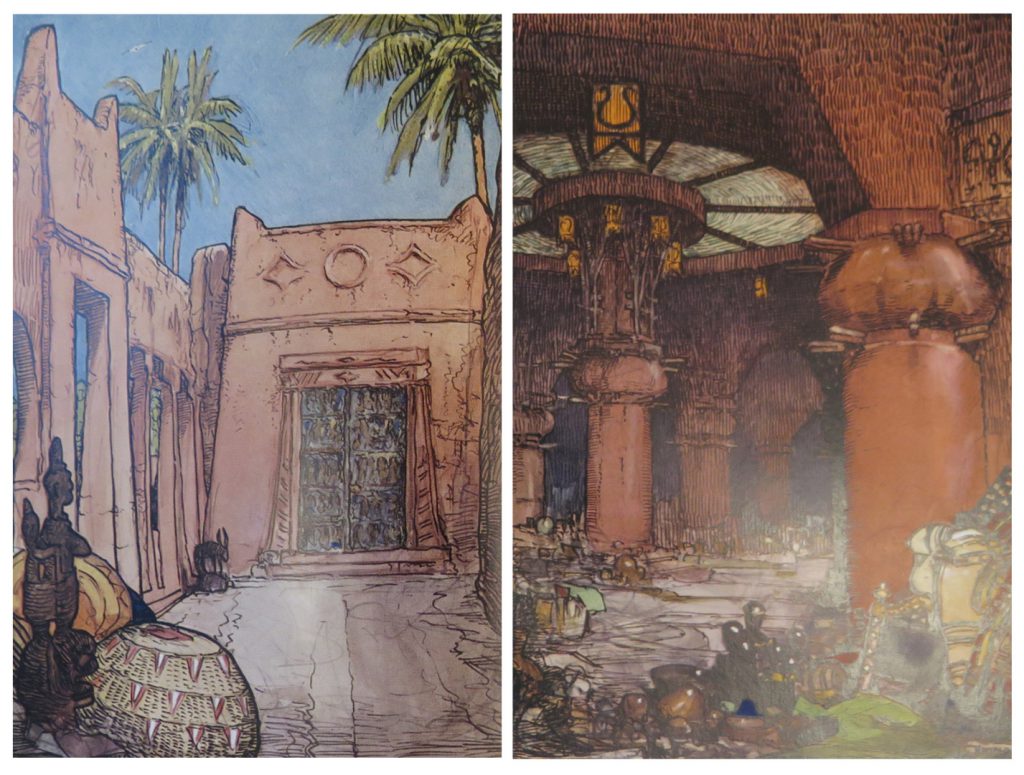

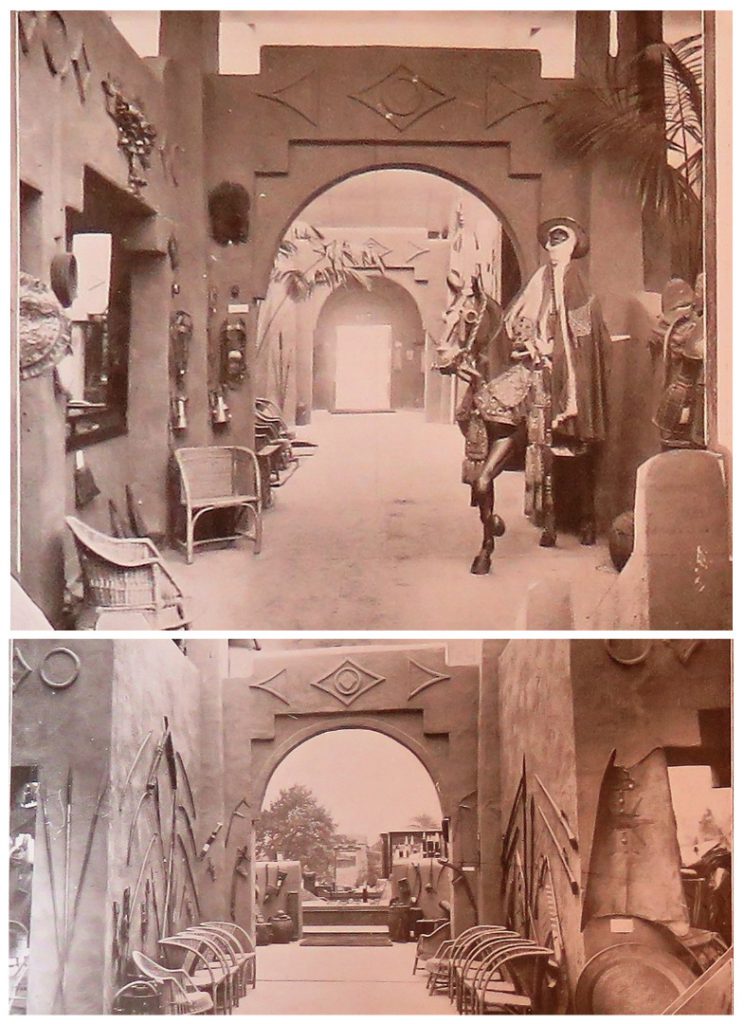

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191101/004The West African Walled-City

The Walled-City was a recreation of a West African fort, which housed three national pavilions – Nigeria, the Gold Coast, and Sierra Leone (Handbook of General Information, 1924, p 12). Within its walls, curators sought to show that “violence” and “idleness” were no longer the order of the day, and that West Africans were cooperating with British paternalism. The Walled-City displayed West African cultures, arts and artefacts, as well as living peoples, including Asante “Princess” Baa, who were paid to wear traditional dress, sleep in thatch huts, and spend their days crafting curios in an ethnographic village (Clifford, 1924, pp 12–17; Rattray, 1926, pp 400–401).[9] Despite the seemingly constructed nature of this village, curators claimed that it reproduced “the exact conditions under which the West African people live” (British Empire Exhibition Official Guide, 1924, p 67). Within its walls, as the official archive makes clear, West Africa was reproduced not as a place of disease and “depravity”, but rather a place of rich and vibrant, exotic culture. An official illustrated publication, rich in romantic language, drew comparisons between sublime European architecture and the Walled-City and described it as follows:

There was something strange about the architecture, and yet there was something to me very familiar. The strangeness was the West African element, but the familiarity was its likeness to certain examples of Norman architecture. I felt that I had entered the nave of Rochester Cathedral in a dream, and that it had been painted red and grown tusks. In the numerous “side chapels” were heaped fruits of the earth, and the whole effect was strongly reminiscent of a harvest thanksgiving.

This direct comparison between a putatively realistic African building and a widely-admired example of Medieval English architecture is revealing. Here, officials wished to demonstrate that Africans (with European help) were now capable of producing buildings comparable to those of pre-industrial Europe. Although this sought to show the “progress” of West Africa, it is an archetypical example of eurocentrism characteristic of this period. European architecture is taken as a standard by which all other cultures are measured, and contemporary African development is regarded as equivalent to that of Medieval England.

Africans were not only depicted as capable of sublime architecture, but were also portrayed as amiable, industrious and cooperative with British rule. Donald Maxwell, author of an official publication, Wembley in Colour (1924, p 19–20), wrote that he had “expected to be at least beheaded by a fearsome-looking ebony potentate” but “was relieved to find that no less charming a ruler than Lady Guggisberg, the wife of the famous Governor, Sir Gordon Guggisberg was to pronounce sentence”. Rather than performing rituals and war-dances as was often the case in earlier ethnographic villages, these Africans were paid to work. Time-disciplined Africans worked by the hour, from opening to closing time every day. Likewise, catalogues and pamphlets accompanying the Nigeria and Gold Coast sections made comments about how, through British intervention, West Africans had become cooperative labourers.[10] Such imperial propaganda sought to demonstrate the “successes” of the so-called “civilising mission”: West African societies, curators suggested, had been disciplined into accepting European conceptions of industrious labour.

Not only were West Africans shown as industrious, but the land itself was depicted as a healthy source of endless resources. Environments were rich in trees to fell, and minerals to extract.[11]This was perhaps best demonstrated by a series of films, screened within the Walled-City, which were visited by 83,015 people (West Africa, 19 December 1925, p 1691). A good example of these is British Empire Exhibition Official Guide, 1925, p 23).

These declarations of success from official sources reduce visitors” experiences to a set of numbers and figures, revealing little about how visitors actually engaged with the displays. They need to be treated with suspicion. Despite its record-breaking numbers of visitors, the BEE had not covered costs in 1924 (Stephen, 2013, p 137). More than attempting to show how years of planning and investment had paid off, they hoped to boost interest for a potential second season to recoup their losses. It was in their interests to be self-congratulatory.[18] Their efforts were ultimately successful, and the BEE was reopened for 1925. Yet both exhibits, as I shall show, were fraught with internal contradictions and paradoxes which threatened to undermine their messages.

Internal contradictions and the curatorial paradox

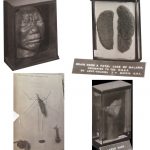

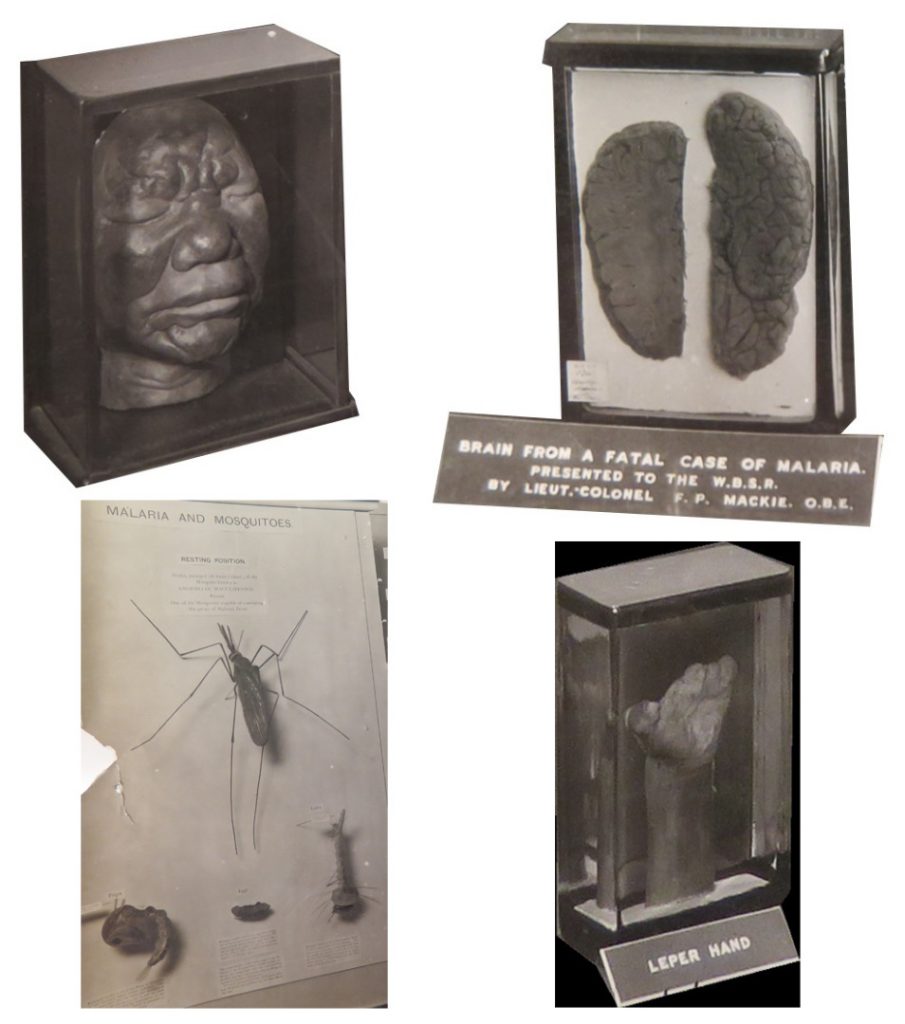

In the case of the Tropical Health displays, curators sought to demonstrate that tropical disease was a worthy adversary for medical minds, but that British medicine was overpowering it. The message depicted was that all diseases had, in the past, caused considerable damage, but were now under control. Yet to show how dangerous and disfiguring the diseases could be, they made use of the long medical tradition of curating images and models of symptoms, insect and parasite vectors, and morbid curiosities: items visually associated with illness rather than health (Rolleston, 1924).[19] In the case of the Walled-City, glimpses into the putative dangers of West Africa (weapons of war, ferocious animals, and venomous insects) had been included as evidence that a once hostile region had become habitable, thanks to British intervention (Clifford, 1924, p 12–17).[20] For both exhibitions, this produced a curatorial paradox: curators sought to manipulate the very images that defined the White Man’s Grave in order to challenge this concept. Even as they exhibited the agents and effects of death, violence and disease, they hoped to convince the public that these problems were things of the past. This was done primarily by contextualising visuals with textual accompaniments in the form of captions and catalogues, as well as some visually arresting features (Rolleston, 1924). Such an approach was risky: the message about medical advances was delivered with subtlety, and conveyed primarily through captions and catalogues, while the visual material suggested danger and disease that spoke to fantasies and fears of the White Man’s Grave. The agency of the objects and images, and the associated curatorial paradox, was intended to be grounded by the textual elements.

In assessing the degree to which the official message of triumph over disease and primitivity was comprehended, it is necessary to uncover the extent to which curators could control and contextualise the visual material. That is, whether the agency of the artefacts could be bounded to serve their intentions, rather than reinforcing previous prejudices of the viewers. To manage the curatorial paradox, curators required two things of visitors. Firstly, they needed them to actually read the displays within the milieu of each individual exhibit, so that the images of death and disease remained thoroughly contextualised. Secondly, they needed visitors to study the displays in detail, along with their published catalogues and guides to fully comprehend their messages.

Uncovering reception and visitors’ experiences

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191101/005Delight, dissent and debate: expert visitors and detailed exhibition visits

Some expert visitors did seem to experience the exhibitions as intended. Medical Officers and Public Health officials from South Africa, Palestine, the USSR and Japan visited, and were reportedly impressed, having “gone away with much information as to the latest progress in Public Health work”.[21] The Chief Medical Officer of New Zealand was particularly enthusiastic, and after the BEE closed in 1925, he requested that its medical sections be dispatched to Dunedin for a special exhibition in 1925–26.[22] Likewise, various distinguished visitors to the Walled-City were given private tours, and were apparently impressed by the displays. One of these, the Nigerian Emir of Katsina, inspected the exhibit, viewed its displayed films, and met with the Nigerian craft-workers. He was reportedly “particularly charmed with his reception” (West Africa, 20 September 1924, p 999) and awed by the fair as a whole. He stated, “through an interpreter that Wembley stood alone easily; he had never seen anything to equal it” (The Manchester Guardian, 2 October 1924). The Colonial Secretary, J H Thomas was given a detailed tour of the city, and took great interest in West African industries, histories and peoples. He remarked to Lady Guggisberg, wife of the governor of the Gold Coast, that “you must be very proud of your people”. To which Lady Guggisberg promptly answered, “we are” (West Africa, 12 July 1924, p 708A). Psychoanalyst Carl Jung was also fascinated by the Walled-City. In his Memories, Dreams, Reflections (1961), he wrote that he “was deeply impressed by the excellent survey of the tribes under British rule” at the BEE, which inspired him “to take a trip to tropical Africa” (1989, p 253). At the end of the 1924 season, a reporter for West Africa felt that although the story “that the Gold Coast is the “White Man’s Grave” has been hard to live down, much has been done to kill it” (West Africa, 27 September 1924, p 1037).

Other visitors, however, had expected complete verisimilitude, and were left unconvinced. Many settlers in Nigeria and the Gold Coast who had returned to Britain to visit the West African Walled-City found it replete with hyperbole and inaccuracies. Many of their responses appeared in West Africa, a periodical dedicated to the colonial development of that region. One writer, in response to a speech from BEE-planner Lord Stevenson was critical of the idea that disease had been pacified in the Gold Coast, calling this idea “unjust and absurd”. He argued that while tropical medicine had improved the situation, “the belief that somewhere in West Africa careers in agriculture are awaiting thousands of young Britons … is pathetically far from the facts” (2 August 1924, p 778).

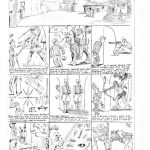

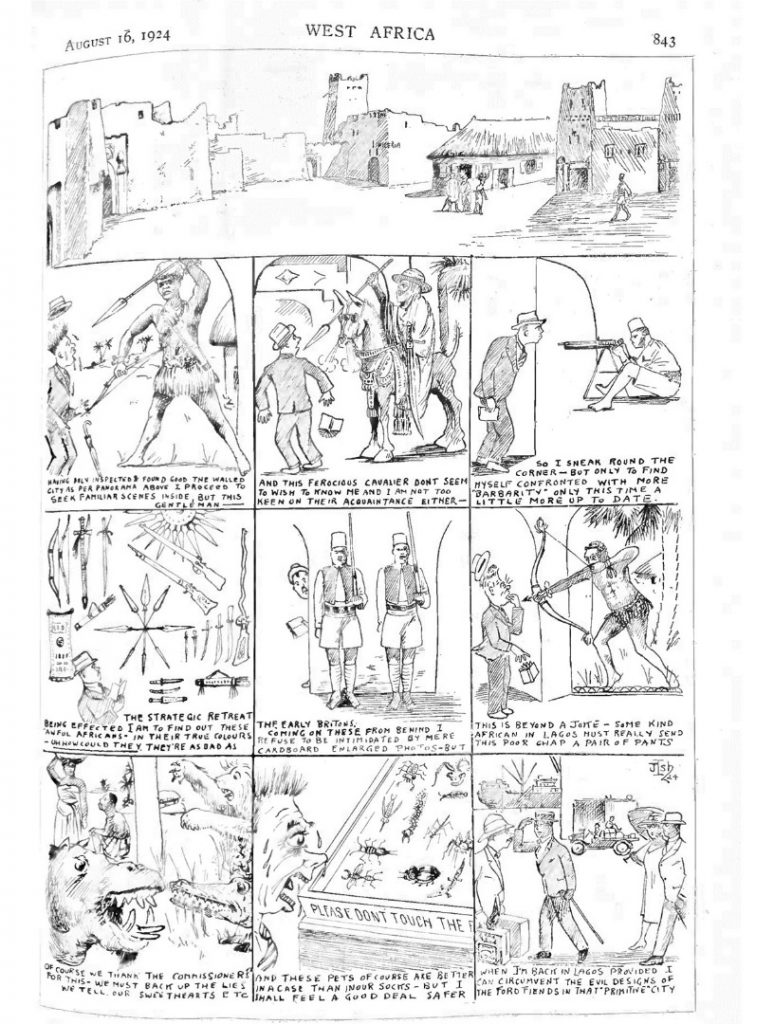

Other settlers in West Africa interpreted the exhibits quite differently: as an inaccurate misrepresentation of Africa as a “Dark Continent”, rather than as the rapidly developing region they had chosen to settle in. They, and West African students in London, lodged complaints on the grounds that curators had gone too far in showing off a spectacle of foreignness, and neglected the realities of West African life (West Africa, 4 October 1924, p 1050). One disgruntled trader wrote to the editor of West Africa (12 July 1924, pp 708A–708B) to complain that while the Walled-City had succeeded in showing “make-believe” African culture, “curios and bric-a-brac”, it had failed to showcase its economic potential. Another trader grumbled that the pavilion represented “primitivity”, rather than the rapid urbanisation that was taking place in West Africa (West Africa, 22 August 1925, p 1052). Perhaps the best example of this is a cartoon in West Africa, which suggested that while real cities like Lagos were sites of impressive development, the Walled-City was a terrifying representation of Darkest Africa. In this cartoon, drawn by a British tradesman from Lagos, the displays were presented as frightening, depicting Africans as violent and primitive, and African environments as dangerous and diseased. At the end, the tradesman flees the terrifying confines of the Walled-City, bound for the comparative comfort and safety of Lagos.

West African students in England were often disgusted by the representation of their home countries. After the publication of an offensive article in the Sunday Express, ripe with “crude sexual allusions” about the workers of the Walled-City, the Union of Students of African Descent (USAD) lodged a series of critiques about the representation of West Africa (Geppert, 2010, pp 167–8). These students protested that West Africans had only been brought to Wembley “to be ridiculed” (West Africa, 9 August 1924, p 801).

In the wake of this controversy, the protest was “generalised to cover all the sights, real and imaginary, felt by educated Africans who visit the show” (West Africa, 9 August 1924, p 801). Some students reportedly felt insulted by the photographs of the “half-naked individual, grimy and streaked with perspiration, whose struggle with nature it is that arouses the interest and respect of an ignorant public” (West Africa, 19 December 1925, p 1703). Others thought that the exhibits had done nothing to showcase the development of West Africa, and reflected only a vision of the past. At a meeting of the USAD, Dr Adeniyi-Jones, a member of the Nigerian Legislation Council complained that while the BEE was “wonderful, he regretted that the particular form of the Nigerian exhibit was that chosen, merely to show a village without … showing the progress made in Nigerian life as a whole, was to give only a partial and incorrect idea of Nigeria of to-day”. This, he felt, would do little to “improve or educate the opinion of the millions of visitors at the Exhibition as to the actual conditions of home life in Nigeria” (West Africa, 4 October 1924, 1050). Mr W F Dove concurred: “All of the West Africans who had seen the Walled City were unanimous in the view that it did not give a true picture of West Africa” (Ibid).

These complaints were articulated throughout the 1924 season, and the issue became so controversial that when the exhibition reopened in 1925, the Africans” living quarters were closed off to the public entirely, although visitors were still free to watch them working at their crafts (West Africa, 23 May 1925, p 557 ; West Africa, 6 June 1925, p 3, p 7). Both the students and (reportedly) the African workers themselves were pleased with this change because they had come to “demonstrate to us their handicrafts and skill. They did not like their home life being the object of public curiosity” (West Africa, 6 June 1925, p 7).

These expert visitors with personal experience of tropical Africa, or training in public health, were not the only inhabitants of the fairgrounds who carefully studied the displays and left records of their experience. The Government Pavilion was staffed by “demonstrators” – guides who were paid to explain certain sections of the exhibits to the public. The experience of J W S Fawcett, employed by the Ministry of Health, is revealing. As a demonstrator, his role involved intimate knowledge of the displays, and a great degree of public interaction. Perhaps disgruntled by his working conditions, perhaps seeking to lobby the government for more funds for the proposed 1925 season, Fawcett delivered a scathing polemic against the Ministry of Health’s exhibition. This, he felt, was not an environment conducive to learning, but a hot, sticky mess of people, clambering to gawk at images of disease and decay. “General visitors”, he felt, had been interested in looking at, but not learning from the displays. To him, the hundreds of visitors per hour was not an adequate metric for success. Instead, he saw crowds obscuring the displays, preventing visitors from examining them in detail, and forcing them to push through throngs of people without learning much at all.[23] To make matters worse, because the visitor had “so much to see and so little time in which to do it … he could not afford to stop and examine each exhibit carefully and ascertain the interesting features”.[24] Furthermore, the catalogue for the Government Pavilion, which was intended to help visitors remember what they had learnt, and contained much of the educational material for the medical displays, was a commercial failure.[25]

Perhaps Fawcett’s most pointed critique was that, embarrassingly, an exhibit designed to showcase the medical prowess of the Empire, was itself an unsanitary environment. Crowds of people, a lack of natural light and poor ventilation, wrote Fawcett, led to the experience of inhabiting the space becoming “very oppressive”. Fawcett worked long hours entertaining visitors in a musty, foul atmosphere, with “acrid fumes” wafting across the pavilion from the nearby Admiralty Theatre, no doubt exacerbated by the fact that the “washing of the gallery floor … left much to be desired” and rain leaked through the roof during every storm.[26] Fawcett’s experience was one which suggested illness, rather than health. To him, the exhibit’s only successes were a series of spectacular displays. For example, the Sewage Disposal section had succeeded in piquing the interest of the public who, like flies, congregated around photos of sewage drains, only to quickly lose interest.[27]

These visitors and participants all had different expectations, expertise and aims with their critiques and comments. Public health officials, interested in devising new ways of preaching health and hygiene, were impressed to see it communicated in a simple and striking way. Settlers in West Africa felt that their experience of the region afforded them a degree of expertise with which to assess the accuracy of the displays. Indigenous West African students were hoping for a favourable representation of their countries to combat ubiquitous stereotypes about African “backwardness”. These students were disappointed when they only found primitivity reiterated. Even for these expert visitors, many of whom conducted careful studies of the displays, curatorial messages were often fragmentary and incoherent. Representation had escaped the confines of curatorial intent: in some cases, triumphant declarations of development were directly contested. In others, sections officially representing progress were interpreted as showcases of primitivity. The voices of these experts, however, do not encapsulate the experience of those millions of visitors who, as Fawcett pointed out, did not have the time to study the displays in great detail.

Immersion, sensuality and fantasies: interpreting “general visitors” narratives

Press material and unofficial guidebooks are replete with evidence that there was simply not enough time for “general visitors” to see the fair in its entirety. Although curators had hoped that visitors would visit the BEE multiple times, this was not a possibility for most. The attendance of Londoners was disappointing – more than two million people had decided not to see it (The Times, 1 November 1924, p 13).[28] The remaining “invading armies” of visitors came from other parts of the UK, the colonies, Europe, the Americas and Japan (The Times, 29 July 1924, p xiv). For these tourist visitors, time was limited, and multiple visits more difficult. Several guidebooks and press articles noted this problem: one review claimed that “a week is barely enough to glance over the surface” (The Times, 23 April 1924, p xix). The official guidebook begged that visitors not “attempt to “do” the Exhibition in one afternoon … That way leads to headache” and warned that visitors “cannot see it all in one day … Try to arrange at least five visits, but better fifty” (British Empire Exhibition Official Guide, 1924, p 13).

In spite of this, the fair did incorporate some features catering for visitors with limited time. It included a “Never-Stop” railway – a train that would give visitors a whistle-stop tour of the fair (Ibid, p 12). Likewise, guidebooks did try to provide condensed tours of the exhibition – one offering both one and two-day tours (Walks in Wembley, 1924). This exhibition itself was, after all, an attempt to encapsulate the “empire in microcosm” (The Scotsman, 24 April 1924, p 6). The Prince of Wales called the BEE the Empire’s “shop window” – an enticing vignette of what might lie inside (Manchester Guardian, 17 January 1924, p 15).

How exactly did visitors with limited time navigate the 238-acre fair, and how did they interpret the African exhibits? Visitors boarding the “Never-Stop” railway, walking down the streets of the fairgrounds, into and between its pavilions, must have experienced a bombardment of unfamiliar sights, smells and sensations. Few visitors perusing the Empire’s shop window in a single day (or a few days) could have studied displays in detail, unless they arrived with specific knowledge of, and interest in particular pavilions or cultures. The “general visitor”, whom curators had so ardently sought to educate, would not necessarily have seen a clear, organised and taxonomic display of culture, but rather a clutter of sensory information associated with foreign places and peoples. Essentially, this would have been what Armstrong (1992, p 199) calls a “jumble of foreignness”. To Armstrong (1992, p 203–242), because the experience of navigating a World’s Fair was almost like a trip around the world, visitors pieced together assumptions about “the other” from various sources, frequently conflating peoples and displays, rather than necessarily distinguishing them hierarchically. Indeed, in retrospect, The Times itself (14 January 1927, p 10) conflated the East and West African pavilions, even though these were two clearly demarcated and completely different buildings. Evidently, some visitors were inclined to confuse the images of Africa they encountered, failing to discriminate between different curatorial zones.

The evidence in support of these speculations is fleeting and anecdotal. Some visitors” testimonies survive in the form of personal accounts and letters to press editors. But by-and-large, such narratives need to be extracted from the experiences and comments of reviewers, themselves often visitors with limited time, and much to see. In these reviews, and associated film, photography and literature, fragments of the affective and immersive experience of navigating the fairground, its sights, smells and sensations, do survive.

Such evidence suggests that partly because of time constraints, the exhausting nature of sightseeing, and the expectation of curiosities that characterised these fairs, most people appeared to have sought out spectacle and entertainment, rather than careful and considered study. Many sources suggest that few visitors were absorbing the captions and catalogues intended to contextualise each exhibit. In the case of the Tropical Health displays, The Lancet (26 April 1924, p 855) recognised that only a minority of visitors would leave with a clear understanding of the complexities of tropical health, stating that “No one who visits this graphic display of tropical medicine and hygiene can fail to be impressed by it; but few, it is to be feared, will realise to the full what it signifies”. An unofficial guidebook included no educational information about the displays, rather employing metaphor by describing the exhibition in militaristic terms – as a battle against disease fought by the armies of science.[29] The British Medical Journal (11 April 1925, pp 703–704), recognising the need to catch the attention of wandering visitors, explained that the 1925 revision of the exhibit had included summaries of the lengthy bodies of text, and a “kaleidoscopic apparatus” to draw people’s attention to the most important features. The new exhibit included fewer technicalities, more spectacular tableaux and arresting visuals.[30] Curators, this suggests, were learning from their audiences.

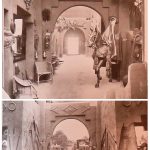

In the case of the Walled-City, like the Tropical Health displays, the evidence suggests that visitors had embarked on a sensorial journey, and showed less interest in the textual propaganda. Jests were made about the heat, coupled with the presence of hordes of school-children, which made visiting the Nigerian building “both disagreeable and useless” as a learning experience (West Africa, 9 August 1924, p 817). Likewise, Africans on display may have been contextualised as educational spectacles, but seem to have been experienced viscerally. West Africa (5 September 1925, p 1118) noted that the major attraction of the Walled-City was the opportunity to experience displayed peoples, claiming that “When the interest of the public in things – inanimate things – fails, interest in our fellow human beings from other parts of the world at their day’s work remains”. A series of Pathé newsreels of the Walled-City demonstrates that various visitors simply passed through the African village, some stopping to peek inside dwellings and others just glancing and walking by. From a viewing of these films, it appears that the congested passages brimming with people and the lack of visible information conspired to offer the visitor an immersive, voyeuristic experience of life in West Africa with little incentive to learn about its achievements in health and industry. Rudyard Kipling commented on the experience, declaring in unrepeatable racist terms that he could almost smell inhabitants of the Walled-City while passing by.[31]

Other sources suggest that this was not a problem specific to these two exhibits, but was characteristic of the BEE as a whole. Punch ran a weekly BEE column, which continuously poked fun at the idea that the various pavilions were exact replicas of foreign cultures, and suggested that while spectacular sights, like the Queen’s dollhouse were always crowded, educational pavilions such as the Palace of Industry were often deserted (Punch, 5 March 1924, pp 238–239; Punch, 12 March 1924, pp 264–265; Punch, 7 May 1924, p 490). Punch was not the only publication to ridicule the idea of the BEE as an educational experience – P G Wodehouse’s story, The Rummy Affair of Old Biffy (2008, pp 140–146), set at the BEE, satirised the idea that visitors were learning about the colonies, their people and industries. Wodehouse’s characters found the exhibits boring, and sought out food, drink and curiosities such as puffed-up fishes, and women performing in the Palace of Beauty. Finally, an interesting hand-written account of a visitor spending “one whole day” at the fair supports this point. It mentions only the architectural and visual elements, such as the splendour of the pavilions, the beautiful dioramas, and various curios for sale. The author writes that “One felt all the time that there was so much to remember and so many scenes to visualise’.[32]

Visions of “Darkest Africa”

Because many visitors were more interested in an immersive experience of otherness than reading textual captions and catalogues, a chasm emerged between curatorial intentions and the experiences of a multitude of visitors. Accounts of the sights, emotions and sensations associated with the Tropical Health exhibit do not paint a picture of West Africa as desirable. One unofficial guidebook claimed that the Tropical Health displays were “rich in nightmares for the sensitive youth” (Walks in Wembley, 1924, p 19). The Lancet (26 April 1924, p 865) declared that despite its hopeful outlook, “its realism must be almost painful to some laymen”. The Manchester Guardian (19 September 1924, p 11) called it “grim, yet fascinating”, and The Observer (21 September 1924, p 15) called its various models “ghostly” and “sinister”. The Times (29 July 1924, p xiii) interpreted the exhibition as a battle of “MAN VERSUS MOSQUITO” where “the question whether man or insects will finally triumph … has by no means been settled” – suggesting a continuing struggle with disease, rather than a situation under control.

The same was the case with the Walled-City. Rather than reinterpreting Africans as industrious, peaceful and cooperative, for many visitors the experience was one that suggested adventure tempered by violence and danger. The arresting images were those of spears, rather than hoes and ploughs – the evidence of supposed primitivity, rather than industry. One retrospective article called the Walled-City a place which could “never [be] entered without a feeling of adventure” and a museum to “heathen gods and pagan customs” (The Times, 14 January 1927, p 10). Much like in earlier colonial expositions, The Times made it clear that this was a place for the intrepid and the brave. It drew attention to its fearsome exterior, and depicted the Walled-City as having:

a character of its own. Other buildings may suggest dignity, others grace, but the West African Pavilion, looming grim and rugged, is suggestive of the adventure and the splendid romance of Empire-building … Its rugged battlements speak of raids and sudden danger; its loopholes frown down upon the broad walk outside.

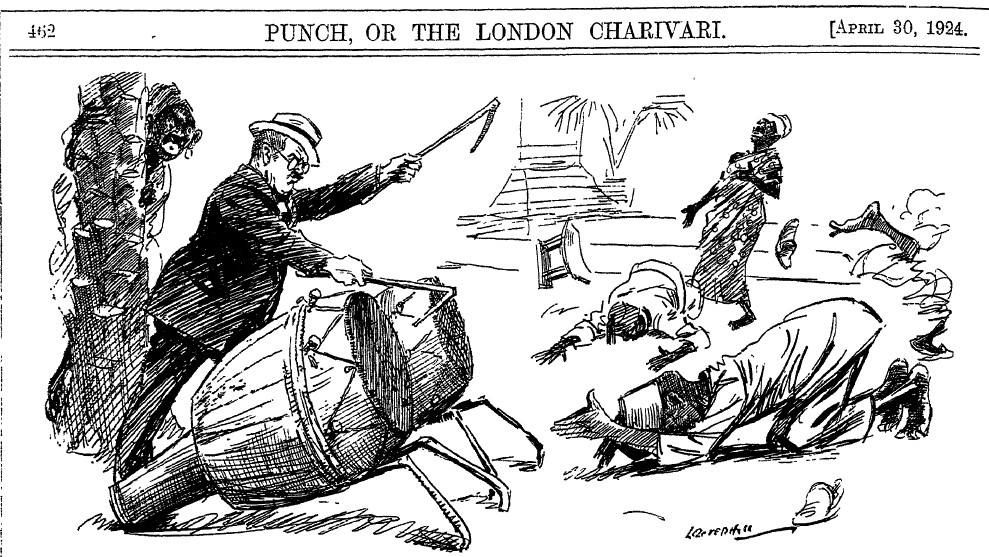

Such ideas of romance and danger were, no doubt, exacerbated by the Prince of Wales’s visit to West Africa in April 1925. Curators of the Walled-City used this visit to generate publicity for their pavilion’s reopening in May 1925. The Prince’s visit did little to challenge dominant stereotypes of West Africa as “barbaric”. On his first day in Kano, Nigerian leaders had cleared the streets of all Africans, to “avoid offense to the senses of sight and smell” (West Africa, 4 July 1925, p 789). The Prince complained about this, and completed the rest of his tour as an anonymous tourist, only to discover a gory corpse. This unfortunate man, a thief, had been killed while resisting arrest, his body left in the open because the “Native official responsible” had planned to watch the Prince playing polo, rather than identify it (West Africa, 4 July 1925, p 789). This extraordinary tale contradicted the curators” vision of productivity and “civilisation”, reinforcing the stereotype that Africans were supposedly unable to maintain law and order. Other articles reported primitivity, rather than violence and incompetence. Punch, for example, suggested that Asante workers in the Walled-City were beholden to a talking-drum which was believed to issue messages from the spirit world (Punch, 30 April 1924, pp 462–463). Such drums were in fact a successful means of long-distance communication used widely across West Africa (Carrington, 1949).

Even Captain Rattray, an anthropologist of Asante peoples, suggested that displayed Asante workers were unable to comprehend their experience of England, and the BEE. They had allegedly interpreted it not as a physical place, but a “visit to the samandow (land of spirits)” (Rattray, 1926, p 402). Frequently, the Walled-City was interpreted as a site of Romantic imagination, an opportunity for musing, a fantastical place, rather than an educational display communicating real life issues and challenges.

For many visitors, tropical Africa was perceived not only as a place of violence and primitivity, but also, perhaps partly as a result of the Tropical Health exhibit, a White Man’s Grave. The declarations that West Africa was now as healthy as London did little or nothing to shift perceptions shaped by earlier prejudices and expectations about African bodies amongst racist Britons. Catering to these authorities ensured that Africans on display (unlike white settlers from West Africa) were inoculated and vetted for tropical diseases (Rattray, 1926, p 395). The Lancet (31 May 1924, p 1127) proclaimed that careful health and sanitary services were “more important than it has been in the case of former exhibitions” because of “a very considerable permanent population in the Park largely unused to Western ideas of sanitation”. Public Health (November 1924, p 61) made sure to notify its readers that all “Native Quarters” were inspected daily by European officials so as to ensure that they were cleaning and using them correctly. In reporting the successes of the Walled-City in 1924, West Africa listed the cleanliness of African facilities. It noted that not only were toilets kept “in a thoroughly clean and sanitary condition”, but also that “no serious case of illness has occurred” (West Africa, 1 November 1924, p 1215). To keep things this way, the prevailing view suggested that Africans had to be kept separate from Europeans as far as possible. They could coexist on British terms within the Walled-City – but not outside – they were “not allowed to leave the Walled City except by special permissions and under suitable escort” (Ibid).

Last of all, Africans visiting the BEE from the colonies struggled to find housing due to social segregation in the surrounding area. This stimulated the Committee for the Welfare of Africans in Europe to create a network of contact details for English landlords who were willing to house them at an affordable price.[33] Some activists even suggested that in order to deal with this problem, Africans should be kept offshore in steamer ships – so as to avoid racist Britons who might cause “harm to British-African relationships” (West Africa, 19 January 1924, p 1675, quote on p 1687). Even if we assume that visitors received the Tropical Health exhibition and Walled-City’s message loud and clear – that Africa was supposedly medically safe for settlement and investment – the situation on the ground told another story.

Objects, images, the senses, and their capacity to resist curatorial intent

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191101/006Such a range of experience in what may seem to have been a fairly clear-cut propagandistic display of the “achievements” of colonial development was possible because the textual and sensorial material offered varying, often incoherent, and fragmented sources of information. Exhibitions were not necessarily appreciated as unified wholes, but were often consumed by visitors as a pastiche of information. Captions, catalogues and careful official contextualisation were suggesting that West Africa was becoming a place of peace and prosperity for British people. Meanwhile, its arresting features: the architecture, morbid curiosities, displayed weapons, peoples and animals, when considered within contemporary European fantasies and fears of “Darkest Africa” told a story of romance, danger, decay and disease. Curators had anticipated visitors arriving ready to absorb knowledge, rather than immersed in pre-existing social and cultural beliefs and ready to embark on an immersive, voyeuristic adventure into otherness. Thus, the curatorial paradox could not be managed, and the agency of the objects and images escaped the curators” bonds, taking on a life of their own.

Indeed, when taken out of curatorial context, and considered within prevailing stereotypes of “the White Man’s Grave”, photographs and models of disfiguring tropical diseases and their villainous vectors – mosquitos, worms and flies – did not suggest health and vitality. These had the potential to produce quite the opposite effect, as the following series of striking and sinister photographs of the displays suggest:

In the case of the Walled-City, the displays of industry, vitality and abundance were intermingled with those that evoked darker British perceptions of West Africa – wild animals, weapons and warfare. These had been included to demonstrate the “achievements” of the “civilising mission”: curators sought to suggest that Africans had abandoned conflict, were cooperating with paternalism, and conforming to British ideals of African development. As Hugh Clifford (Governor of Nigeria) put it, they had “turned their spears into implements of agriculture” (Clifford, 1924, p 13).

However, many visitors did not interpret these as images of African “progress”. Instead, curatorial visions of the past were taken to be visions of the present. Images of disease and danger latched onto and reinforced pre-existing prejudices, in many cases offering yet another window onto “Darkest Africa”.

Conclusion

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191101/007In this study, I have argued a need to bring official curatorial intentions into conversation with fragments of sensorial experience which survive in print media, literature, film and photography. Through comparing these different kinds of sources, I have uncovered a multiplicity of potential experiences within the BEE. The interpretation of images, artefacts and peoples often escaped curatorial intent. Visions of a new “white man’s home”, could be challenged and discussed, and even be read as reiterations of the familiar image of the White Man’s Grave. One reason for this was contemporary context: a prevailing history of ideas, images and sensations related to Africa had been disseminated in earlier exhibitions and other media, and a plurality of pre-existing discourses surrounded the objects on display. Another reason was the capacity for visitors to treat the experience as an adventure into otherness, rather than one of careful study and close reading. A third hinged on a curatorial paradox – curators sought to manipulate the very images that had defined the ‘White Man’s Grave’ to challenge it. These findings have several implications for the historiography of exhibitions, popular science and imperial culture.

Here, I have shown that there is a great capacity for the sublime, immersive and sensational experience of an exhibition to overwhelm its intellectual messages. Imperial culture and popular science need to be understood as more than just a negotiation of intellectual ideas and mentalities. We also need to consider the sensual, somatic, material and affective dimensions of these mentalities. The visceral horrors of disease, fed by popular science, literature, film and visual culture often defy any rational attempt to contextualise risk. Drawing attention to the sensorial aspects of the cultural history of medicine also allows us to reflect on the legacy of prejudice about African peoples and environments which persists to this day.

Secondly, this suggests that we need to continue to rethink and challenge the relationship between international expositions, national identities and twentieth-century concepts of modernity. The British Empire Exhibition was not only a place of “pilgrimage to the commodity fetish”, as Benjamin so eloquently described the archetypical international exposition (2002, p 7). Nor was it always a site at which unified national identities were formed. Instead, it exposed the tears and frays within the tapestry of the British Empire, at a period in which its weave was rapidly unravelling.

Finally, I have demonstrated the limits of using the archive of the fair to unearth European perceptions of other cultures. Curatorial intentions are often highly politicised and are not always representative of visitors” opinions. Visitors experiences survive only in fragments, and cannot be homogenised as singular. Different degrees of expertise, personal experience and expectations resulted in varying interpretations of the exhibits, rather than a singular narrative being read. There are limits to curatorial power, and in this case, a lineage of racist ideas could not be challenged by the very same sensory tropes which created them in the first place. Believing was seeing, and many of those exploring the Walled-City and the Tropical Health exhibit saw only what they already believed the reality of Africa to be. Curatorial visions of productivity were often perceived by visitors as primitivity. Those who had lived in West Africa were often unconvinced that the Walled-City resembled contemporary African life. In either case, the fantasy that curators had put on display did not always correspond with the imagined reality on the ground. Many visitors” eyes were accustomed to the stereotype of the dim, gloomy jungles of “Darkest Africa”, and curatorial glimpses of light failed to penetrate its dark canopy.

Acknowledgements

This article was derived from my MSc thesis, produced at the University of Oxford in 2016–17 and funded by the Standard Bank Derek Cooper Africa Scholarship. My sincerest thanks to my supervisor, Sloan Mahone and the Wellcome Unit for the History of Medicine for providing a stimulating and encouraging research environment. My thanks also to Pippa Skotnes and Alex Grieve for reading drafts of this paper and for their encouragement and critical feedback. Finally, I am tremendously grateful for the support provided by the Science Museum Group, particularly Kate Steiner, Richard Nicholls, the editorial board and judging panel, as well as three anonymous reviewers, whose feedback significantly improved this paper.

Tags

Footnotes

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text