Wounded: Healing communal wounds: processions and plague in sixteenth-century Mantua

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191106

Abstract

In 1576 a plague epidemic inflicted physical and psychological wounds on the community of Mantua. This article examines the role of processions in healing those wounds and discusses the programme of processions organised by the city’s health office in conjunction with religious groups including Mantua’s confraternities. Processions were staged at various points during the epidemic for different purposes: to celebrate dates on the religious calendar, such as the feast of Corpus Domini, and to reintegrate those cured at the plague hospital to the city. Participation was not limited to those in the processional body; for instance, people quarantined in their homes could watch the event, hear the prayers, and join in by singing. Therefore, processions provided a link between the sick and the healthy and illustrate the collective experience of illness and healing in early modern society. Furthermore, processions with returning convalescents in Mantua illustrate complex attitudes towards the sick poor and their role in healing the city.

Keywords

confraternities, health offices, Mantua, Plague, premodern public health, processions, ritual

Introduction

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/On Wednesday 6 June 1576, a group of 113 convalescents were released from a plague hospital near the city of Mantua in northern Italy.[1] They were met by members of the Confraternity of the Forty Hours, one of Mantua’s lay religious brotherhoods, and taken to a church where they heard mass and were given a meal. Afterwards, the Confraternity of San Antonio took the group in procession through the streets of the infected city. As the convalescents were poor, they were given food, lodging and charity. This was the first in a series of processions that celebrated the return of previously sick members of the community.

Processions were an important part of the public health response to plague epidemics in early modern Italy. This article contributes to pre-modern public health scholarship by exploring them as an example of the intersection of civic and religious responses to plague. The resulting argument underscores the view of public health suggested by Kristy Bowers, that balances were struck between the needs of the individual and the community to improve health in an infected area (Bowers, 2007, p 339). This article further suggests that cooperation between Mantua’s civic health board and the city’s religious groups in organising processions demonstrates that medical and spiritual cures were closely aligned. This reinforces scholarship that has challenged the view that processions were incongruous with medical concerns about contagion and with public health strategies (Cohn, 2010, pp 287–90). However, previous work on processions has focused on organisation, participation, and on the connection between practical and symbolic strategies in pre-modern public health. In contrast this article shifts the focus to emphasise the role of the poor in plague processions. By the fifteenth century plague was associated with poverty (Cohn, 2010, pp 208–237). Brian Pullan has argued the poor had three contrasting roles during plague epidemics, as bearers, victims and beneficiaries of the plague (Pullan, 1992, p 107). As I will show, care for the poor took various forms and the link between plague and poverty shaped Mantua’s response to those who left the plague hospital.

Processions during the 1576 plague epidemic were curated by Mantua’s confraternities and were staged for different purposes: to celebrate dates on the religious calendar, such as the feast of Corpus Domini, and to reintegrate those cured at the plague hospital into the city. Here I will argue that these events offered a sense of continuity and renewal in a cityscape infected by plague and that the processions involving poor convalescents had significant symbolic resonance for the wider population. Convalescents had received medical and spiritual care at the city’s plague hospital and their return marked a civic triumph over the disease and, therefore, had a powerful, healing symbolism for the city. Processions were illustrative of the collective experience of illness in early modern societies and provided a visual and audible connection between the sick and the healthy. By acting as the focus of processions, the convalescents contributed to healing the communal wounds caused by the disease.

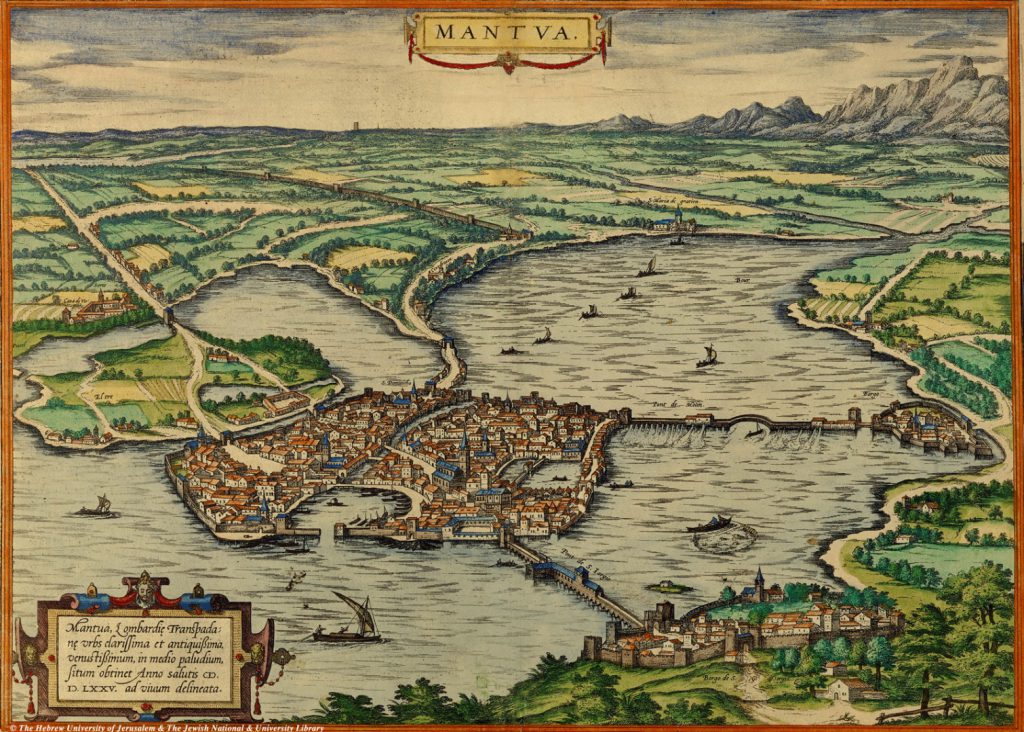

Plague

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191106/002Between 1575 and 1577 the Italian peninsula was beset by arguably the worst plague epidemic of the sixteenth century. Cities in the north and south were infected almost simultaneously (Corradi, 2nd edition, 1972–3, Vol 1, pp 578–625 and Vol 5, pp 334–8; Cohn, 2010, p 19). In the north the disease spread from Trento and its territory to Venice and Verona, then on to Mantua and Milan in 1576 (Lodigiani, 1978, p 364). Following a spike in the number of reported deaths, officials in the city of Mantua announced that it was infected with the disease on 27 March 1576 and a temporary health board was appointed to create and implement public health strategies. The city was treated as a site and potential source of infection, and the job of health officials was to identify those sources and clean or remove them. The regulations and strategies they used were similar to those employed by health boards in other infected cities; restrictions were placed on contact between people, on travel and on trade; people who were infected (or were suspected of being infected) were removed and taken to plague hospitals; and streets were cleaned regularly to remove rubbish. Mantua’s health office was not a permanent entity, therefore health officials worked with, and relied on, religious groups and the broader community to restore the city to good health. Despite their actions approximately one fifth to one sixth of the population died during the epidemic (Belfanti, 1981, pp 65–5).

This threat of an epidemic from both North and South led to a shift in public health activities with civic responses across the region being bolstered by Counter Reformation Catholicism (Cohn, 2010, pp 292–3, p 300). In fact, processions formed part of public health programmes of many Italian cities in 1576 with varying levels of spectacle and participation. In Bologna, a city not infected by plague, a broadsheet printed in July 1576 gave directions for priests of the dioceses, which included holding processions within churches and ensuring the people prayed for the cessation of the plague in infected areas as well as for the continued health of Bologna.[2] In stark contrast, Venice was one of the cities devastated by the epidemic with approximately one third of the population falling victim to it. Venice had both a well-developed public health system and a rich tradition of grand civic ritual (Palmer, 1978; Muir, 1981). These elements combined in plague processions which (along with the worship of relics) Iain Fenlon describes as ‘fundamental weapons’ during plague crises (Fenlon, 2007, p 224). The need to placate the anger of God ‘required urgent and persistent intercession through prayer, charitable works and communal spiritual exercises’ (Fenlon, 2007, p 224). One such exercise was a procession of atonement held in Venice on 14 August 1576, the feast of Saint Roch, a saint that became associated with healing the plague (Boeckl, 2000, pp 57–8). Groups from every parish in Venice met outside the saint’s church and processed as a group reciting prayers and chanting litanies (Fenlon, 2007, p 225). In September 1576, after a terrible summer, the Doge, Senate and other members of Venice’s governing body processed around the piazza of San Marco on three successive days. Given the seriousness of the situation the Venetians processed with a special Byzantine art work thought to bring luck to those engaged in war, as it was felt the city was at war with the epidemic (Fenlon, 2007, p 225).

In neighbouring Milan, Archbishop Carlo Borromeo played a prominent role in organising the public health response, combining secular and religious care to galvanise the Milanese public health strategy and fight the disease. Borromeo organised three processions in October 1576 (Jones, 2005, pp 68–70). As in Venice, one of the most powerful, important relics belonging to the city was deployed – a fragment of the Holy Nail – which was carried in procession around the city. Participants in these elaborate processions sang hymns and litanies as they walked through infected streets, involving whole communities in the event. As David Garrioch has argued ‘participation in religious services and processions marked by bells and singing helped shape a spiritual community that was also a local one’ (Garrioch, 2005, p 15). These processions reinforced the bonds of a local spiritual community while invoking powerful, saintly intercessors to rid the community of disease. Hymn sheets or pamphlets were printed to be carried while on procession (Chiu, 2017, p 105). Remi Chiu argues that the call-and-response structure of the litany was a useful musical tool that established ‘concord among the discord of the body politic’. Every member of the procession was indispensable to the success of the ritual. Further,

as the penitents sing the litany on the march, they send out an audible pulse through the march group and provide an ambulatory rhythm that unites the participants. Weaving back and forth, the litany acts as a sonic thread that holds together the constituent parts of the processional body

The sonic link was not limited to those in the processional body. People quarantined in their homes could also see the procession, hear the music and prayers, perhaps smell the incense, and join in with singing as it moved through the city streets. During plague epidemics many social bonds were fractured, and so the familiar ritual of a procession in a landscape altered by crisis provided an important link between the sick and the healthy. The processions held in October 1576 were thought to have been so successful that a contemporary Milanese writer remarked they were the principle cause for the city’s liberation from the plague as they helped to placate God’s wrath against the Milanese (Cohn, 2010, p 287). The processions held in Venice and Milan unified secular authorities and religious groups in city-wide demonstrations of piety with the purpose of mitigating the effects of the disease.

Processions in Mantua

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191106/003In Mantua the relationship between civic health officials and religious groups was different in tone. Mantua had not experienced a plague epidemic for almost fifty years, therefore, the temporary health office had to create or reconstruct public health strategies in the city and negotiating with others was crucial to this process. The correspondence of health officials shows that they sought to establish balance between actions that could cause harm to health (such as people gathering in groups in close proximity) while recognising the power of collective, pious actions. During the epidemic, movement within the city and gathering in groups was restricted and normal activities were assessed for their risk to health; dancing was banned, for example, and public schools were closed.[3]

Thus, while processions filled an important role in the civic life of early modern cities, in the infected city they posed a potential threat. For instance, a procession that formed part of the usual liturgical calendar provoked debate among the health office, the Bishop of Mantua, Marco Gonzaga, and the Duke of Mantua, Guglielmo Gonzaga. Their consultations show that practical health concerns and spiritual needs were both taken seriously. On 11 June Bishop Marco Gonzaga raised the issue of the annual Corpus Domini procession with the ducal secretary. While he recognised the need to avoid a large gathering of people, he believed that ‘in the present uncertain times one must keep the people in the devotion and fear of God’.[4] He acknowledged the need to restrict movement to stem the potential for spreading infection while arguing for the spiritual benefits holding a procession would give the community. Accommodations were made both by health officials and religious groups to reach a solution. The following day the head of the health office, Paolo Bardellone, also raised the question of the procession with Guglielmo Gonzaga. He commented that the bishop and many citizens who visited the health office had reported that the people in the city greatly wished it would happen.[5] This emphasises that dialogues about public health concerns extended beyond governing bodies, and that ordinary people subject to the regulations could have an active role in shaping premodern public health. Thus balances were struck between individual and communal needs, as well as between the civic authorities and the inhabitants of Mantua.

Discussions about the Corpus Domini procession centred upon the practicalities of participation. Bardellone suggested that only clergy would be allowed into the church of Santa Paola. Men would be employed to control the crowd to ensure that they followed in rows of four or five, not in confusion.[6] In order to please the people, and with the suggested precautions, Guglielmo Gonzaga allowed the event to take place. Additional measures were taken to ensure proper order was maintained: the health office arranged for around fifty men to be stationed along the route to make sure the participants did not cause disorder; two health officials would patrol on horseback to monitor the men stationed on the street; and a proclamation was announced on the day to be certain that everyone was aware of the orders.[7] Afterwards, Bardellone wrote that it had gone rather well, and another observer described the procession as ‘the most beautiful, the most moving, the most orderly that I have ever seen’.[8] Thus alterations were made and sanctioned by the health office in conjunction with other groups to ensure the event posed minimal danger to health but also contributed to the overall attempt to improve the health of the city.

Convalescents return

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191106/004Corpus Domini was an important, familiar ritual event that offered a sense of continuity in a plague-stricken city. However, as with the processions held in Milan and Venice discussed above, the participants were healthy members of the civic and religious groups. Another series of processions wound through the infected city streets that arguably had a greater symbolic resonance in the fight against plague. The main participants were the patients who had been taken to Mantua’s plague hospital and, having survived illness and a period of quarantine, were ready to return to the city. These convalescents were predominantly poor people, including women and children. Therefore, their reintegration in to the city was not only a mark of the Mantuan health office’s triumph over the disease, it also demonstrates the important link between health care and the provision of Christian charity as the convalescents were cared for by the city’s confraternities. The health office worked with a number of other groups and organisations in the city to provide charity for the poor and especially the sick poor. The conjunction of civic health care and the city’s charitable institutions is a further example not only of cooperation between groups, but of the fundamentally important role that confraternities played in Mantuan public health care provision. Paul Murphy has examined the life and career of Cardinal Ercole Gonzaga who, while acting as regent for the young Guglielmo Gonzaga, implemented religious and governmental reforms earlier in the sixteenth century. Murphy argues that the political situation in Mantua meant that there was a ‘symbiotic relationship between the structures of ecclesiastical authority and those of the local civil government’ and as a consequence lay religious practice, including confraternities, were tied more closely to the aims and requirements of the Gonzaga rulers and the ‘new models of piety fostered in the Tridentine era’ (Murphy, 1999, p 45). This symbiotic relationship is also evident in the actions taken to counter the plague epidemic. Church officials and confraternities contributed through religious ceremonies, poor relief, and by helping to organise the return of those cured at the plague hospital.

The plague hospital was central to the corpus of counter-plague measures employed in the Italian peninsula and beyond. Ann Carmichael has argued that from the mid-fifteenth century many northern Italian cities decided that the plague hospital was ‘the best solution to the problem of plague’ (Carmichael, ‘Plague Legislation’, 1983, p 513; see also Stevens Crawshaw, 2012, pp 21–2). Carmichael describes them as effectively ‘an emunctory to drain the putrefactive plague stricken away from the heart of the city’ (Carmichael, ‘Epidemics’, 1998, p 229). Mantua did not have a permanent plague hospital as other larger cities, such as Milan and Venice, did. The health office instead commandeered the almost empty Monastery of San Pietro d’Ongaria near Cittàdella, which was not on the island city. Those infected with the disease and those suspected of having the disease were taken there to be treated (often accompanied by their worldly goods, which had to be cleaned and fumigated). The temporary plague hospital opened on 1 April 1576 and the first patients were sent there the following day. The monthly death figures for the city, given in a contemporary chronicle, show a sharp decline in recorded deaths from May 1576 following the opening of San Pietro (Vigilio, 1992, pp 48–9). While we must take into account that not everyone who entered the plague hospital had plague, the significant reduction in monthly mortality is strong evidence for the efficacy of removing those infected, or suspected of being infected, from the urban confines of the city.

While at the plague hospital patients were cared for by doctors, given medicines and foods appropriate for their condition, and were also given spiritual care. The challenges around providing the complexity of care required in plague hospitals has been comprehensively examined by Jane Stevens Crawshaw (Stevens Crawshaw, 2012). A contemporary chronicle written by a Gian Battista Vigilio, a minor official in the Mantuan bureaucracy, recorded the number of people who left the plague hospital: 683 of the 1,614 patients. Once a period of post-plague quarantine had been completed, those who survived their stay in the plague hospital could return to the city. The convalescents were undoubtedly a light in dark, challenging times and were seen by contemporaries as evidence of the health officers’ and by extension the city’s success in combating the disease. Their return gave cause for celebration, but it was not without problems. Early modern ideas about disease causation linked the supernatural and natural worlds. The primary cause of disease was God punishing sinful behaviour, which was connected to secondary causes such as corrupted air or contagion found in the environment. The majority of the convalescents were poor, some were orphaned children, and some did not have a home. Therefore, they were at risk of reinfection through poor quality living conditions. There was also concern that if the orphans were not cared for they could be led into sinful behaviour by others.

This problem was not unique to Mantua – the city of Padua also held processions celebrating convalescents’ return from the plague hospital. In contrast, in Venice (as Stevens Crawshaw has shown) those who returned to the city were sent into household quarantine and when released were often put to work by the health office, cleansing infected goods, for example, or helping to treat the sick (Stevens Crawshaw, 2012, p 207). In Mantua the problem was resolved by the health office and the city’s confraternities who worked together to re-integrate the cured back into the community in part through a series of processions. As caring for the poor was a charitable act, their actions helped to placate God’s wrath and hence contributed towards the public health fight against the plague.

The processions for convalescents are described in letters written by health officials and also in Vigilio’s chronicle. Health officials’ letters were primarily concerned with organisation, such as when and how many convalescents would be released, where they would go afterwards, and how the city’s confraternities would participate. The chronicle lists the number of people who were released on each occasion and describes the route of the processions, and occasionally Vigilio gives his own observations on the events. The content of the letters and the chronicle emphasise cooperation between the health office and the confraternities. A dispute did arise, but it was between two of the confraternities and it was resolved by the health office. The Confraternity of the Forty Hours, seemingly jealous of the role played by the Confraternity of the Holy Blood in the previous procession, caused trouble.[9] The nature of the trouble is not made clear in the correspondence, but it was possibly a dispute about precedence (Black, 1989, pp 110). On 28 June Bardellone wrote that he hoped the discord between them would be resolved to the satisfaction of the confraternities, and ‘for all the people’.[10] The following day Bardellone reported that the heads of both confraternities met at his home and made ‘most humble and cordial peace’, asking for remissions from any offence.[11] To show good feeling members of each confraternity celebrated the jubilee for the feast of the Visitation of the Madonna together in the Cathedral the next day.[12] An observer noted that the reconciliation of the two confraternities was so remarkable that he could not describe it well enough and the members hugged each other with kisses and tears.[13] However, the disagreement did have an impact on the provision of charity for the plague convalescents. Vigilio notes that when the fourth group were received by the Confraternity of the Forty Hours and the Confraternity of San Antonio, they received food but not charity because of the dispute between them (Vigilio, 1992, p 51).

Vigilio’s chronicle describes the first release of 113 convalescents on the morning of Wednesday 6 June 1576 as a celebratory and ceremonial event. The convalescents went in procession with the Confraternity of the Forty Hours carrying images of the plague saints, Saint Roch and Saint Sebastian, and were accompanied by beautiful singing (Boeckl, 2000, pp 46–7). They were taken by boat from the plague hospital to the church of Santa Maria delle Grazie where they heard mass and had a meal. Visiting this church was particularly significant as it had been rededicated to the Virgin Mary in thanks for the cessation of a plague at the turn of the fifteenth century. Afterward the convalescents returned to the city where they were met by members of the Confraternity of San Antonio. The now cured patients processed through the city streets past the principal churches of San Andrea, San Pietro, and finally to San Antonio where they were given another meal. Those without accommodation were given a place to stay and each person was given money from the charity that had been collected (Vigilio, 1992, p 50). This began a series of processions that occurred roughly once every month.

Among the first group of 113 people were twenty orphaned children; 15 boys and five girls. The health officials were concerned that these children could fall in to sin (vadino al male) without proper care. They had hoped to be able to send the girls to a charitable house called the Misericordia, set up in 1535 for poor, female orphans. However, the Duchess of Mantua raised concerns about cleanliness of the Misericordia building. The health office persuaded the Confraternity of San Antonio to accept all of the children, including the girls, under the care of the wife of a Maestro Girolamo. Duke Guglielmo Gonzaga had granted the confraternity two rooms that had belonged to a vegetable seller (ortolano) in order to accommodate the orphans.[14] This continuing care for the children left orphaned by plague demonstrates that secular authorities took their responsibility for them seriously and looked beyond the end of the epidemic.

Bardellone prepared for the release of the next group noting that, with the grace of God, approximately another one hundred people would complete the quarantine, many of whom were poor and in need of food and lodging. He discussed the possibility of some being given accommodation by the Confraternity of the Most Holy Blood, who had previously taken in twenty-six convalescents.[15] The Confraternity requested a licence to open a part of their building as a dormitory, and suggested that if they were given some charitable funds they could build another dormitory to accommodate between 160 and 180 of the poor. The health office sought funds for what they called ‘not only pious but also necessary work’[16] and Bardellone added that the Confraternity had written to Rome to give an account of the previous procession of convalescents.[17] A custodian of the Confraternity wrote that the building work began on 18 June 1576.[18] The repurposing and extension of confraternal property further underlines the conclusion that there was a longer-term view of post-plague support for the poor in Mantua.

By the time the next group were due to be released four of the convalescents had died. The remainder of the group were released on the festival of San Giovanni on 24 June. Bardellone wrote that the Confraternity of the Forty Hours met the 96 people released that day and gave them lunch at the church of San Sebastiano. Then they went to the church of San Antonio where were given another meal, and those without lodgings were given accommodation.[19] Vigilio’s version provides an additional observation that the procession stopped at the church of San Andrea where Mantua’s most powerful relic, a vial of the blood of Christ, was held (Vigilio, 1992, pp 50–1). It is not clear if the relic was used in the processions, as in Venice and Milan, but even if the relic did not leave the church, those in the procession would have been aware of the church’s significance.

Thereafter, groups were released approximately once a month, until January 1577. The chronicle reports that the same procession route was followed on 29 July when 135 people were released and Vigilio adds that he saw them all sitting at a table in the piazza in front of the church (Vigilio, 1992, p 51). On 24 August, the fourth group of 98 convalescents returned to the city.[20] The fifth group left on 11 October when, as noted by Vigilio, 61 returned to the city and were again taken to San Antonio (Vigilio, 1992, p 52). Bardellone wrote that among the men and women who had finished their quarantine, 26 were poor and nude and were to be given clothes.[21] Charity in the form of clothing was also given to patients in Venice when they returned from the plague hospital (Stevens Crawshaw, 2012, p 136). On the 22 October, 36 returned to Mantua having finished their quarantine, and were received by the Confraternity of San Andrea as they had been on the previous occasion.[22] The seventh procession took place on 13 December when 99 were released and taken to San Antonio, and 42 convalescents did the same on 25 January 1577, (Vigilio, 1992, pp 52 and 54), with this eighth procession marking the end of the epidemic. One can imagine that holding these events must have helped to lessen the stigma of those returning from the plague hospital as well as providing a regular visual and aural reminder that Mantua’s battle against the plague had some success. Previously sick members of the community were now re-integrated into the city with celebrations and paraded through the streets. The sights and sounds of these processions must have given hope to residents, while trumpeting the success of those governing the city and of the communal fight and triumph over the disease. The charitable provision for the convalescent poor indicates how civic and religious organisations perceived their responsibilities towards the poor both during the epidemic and in the longer term. It also represented in itself an action which would ameliorate the epidemic then seen as an act of a wrathful God on a sinful population.

Conclusion

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191106/005In Mantua processions were a crucial part of the counter-plague strategies implemented by the health office. Despite concerns that gathering people together could exacerbate the spread of infection, alterations were made and sanctioned by the health office in conjunction with other groups to ensure they posed minimal danger to health but also contributed to the overall attempt to cure the city. Perhaps a sign of their perceived success and value was that in a document produced by the health office that detailed 75 actions to be taken during an epidemic, it was suggested that processions take place every two weeks. The cooperation between the health office and Mantua’s confraternities demonstrates the important connection between medical and religious cures and care.

Public health responses to plague epidemics were multifaceted, but ritual and symbolic aspects were fundamental to healing the individual and the community. Processions held during the epidemic were one of the ways by which a community disrupted and separated by the tumult wrought by plague could be brought together in a familiar ritual. Returning the previously wounded bodies of the plague-stricken to the city marked the city’s success in combatting the disease. Chiu argues that the vibrant, singing, processional body acted as a sonic thread as it wound through the infected streets of Milan. In Mantua, this idea can be taken further, as the convalescent processions that walked through the streets acted as a ritual thread with the purpose of bringing the wounded city together, given added resonance and power by those who had survived the disease.

Tags

Footnotes

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text