How Britain’s railways prepared for nuclear war

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/232002

Abstract

As a nationalised industry during the Cold War, Britain’s railways were required to undertake civil defence work to prepare for a future conflict. Civil engineers that engaged with civil defence work were required to understand the destructive capacity of first atomic and later hydrogen weapons as well as the threats of nuclear fallout and radiation so that they could design and build structures capable of withstanding them. At first, these civil engineers objected as the work was beyond their expertise. But from 1952 onwards, each region of Britain’s railways, led by their civil engineering departments, began to build infrastructure and train their staff to prepare for the continued functioning of the railways following a nuclear attack. The central focus of railway civil defence changed as the bomb threat itself evolved, but its central purpose was always more focused on repair work and the assistance of military operations over civilian evacuations. However, shackled to guidance and limited available funding from the UK’s Ministry of Transport and the Home Office, planning was frequently delayed or scaled back. By the mid-1960s, alongside most other British civil defence programmes, the planning was abandoned and government funding withdrawn. But despite the myriad of setbacks and funding disappointments, those that undertook the railways’ civil defence planning and training during the early Cold War saw the value in their work and hoped to contribute to a national effort to survive and rebuild should the worst ever occur.

Keywords

Civil Defence, Civil Engineering, Cold War, Infrastructure History, Nationalisation, Nuclear War

Introduction

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/How do you defend a population from a nuclear bomb? During the early years of Britain’s Cold War, this question was on the minds of many and, unsurprisingly, it did not have an easy answer. During the first few decades of the nuclear standoff between the Soviet Union and the United States, civil defence was a developing field, one studied by scientists within the Home Office (Smith, 2010) with the intention that it would be taught to and practiced by much of the population of Britain. Britain’s railways were no exception to this. As major employers, providers of a key public service, and a nationalised industry, they were tasked by consecutive post-war British governments with preparing measures to continue their functioning during a possible future war. The railway’s involvement in such defensive planning embodies the ‘military-industrial-scientific complex’, which historian David Edgerton has described as the British ‘Warfare State’ (2006). This civil defence work, referred to as ‘Due Functioning’, was shackled to government policy and funding, and, importantly, to government’s comprehension of how a nuclear attack would occur and what damage would entail.

The development of an effective civil defence organisation for the railways was hampered by this reliance on top-down guidance from government. Delays on funding from the Home Office and the Ministry of Transport prevented action from being taken, and guidance on what kind of destruction a nuclear war could bring was often not forthcoming. As a result, the development of civil defence planning was paralysed on several occasions as civil engineers and other railway officials waited for instructions. Each time the nature of the bomb threat evolved, planning faltered. Yet, despite these set-backs, numerous civil defence schemes which did not rely on government guidance or funding were undertaken, sometimes at a surprising scale. Civil defence lectures for railway workers were extremely popular during the late-1950s and early 1960s, and various building projects were put underway, second only in importance to British Railways’ Modernisation Plan.[1] The measures that were undertaken also included some civil defence repair training courses and the creation of stockpiling quotas, alongside the beginnings of an emergency control shelter programme (a series of nuclear bunkers allowing station staff to continue their work) and the decentralisation of major headquarters outside of potential target areas.

By the mid-1960s, nuclear deterrence became the dominant thinking within top-level government. This followed the subsidence of major tension following the Cuban missile crisis in 1962, one of the closest moments the world ever came to Nuclear Armageddon. By then, civil defence was seen increasingly only as a failsafe, or ‘humanitarian work’, which received less and less funding as Britain’s post-war financial struggles worsened throughout the 1960s.[2] As described by Melissa Smith (2015), civil defence went from an ‘insurance policy’ to a part of the deterrence policy increasingly centred on public messaging, the hope of survivability and the restoration of order, rather than the expensive roll-out of protective infrastructure. By 1968, surviving programmes and projects were almost all paused or abandoned; those that persisted languished until the resurgence of nuclear tension during the 1980s.

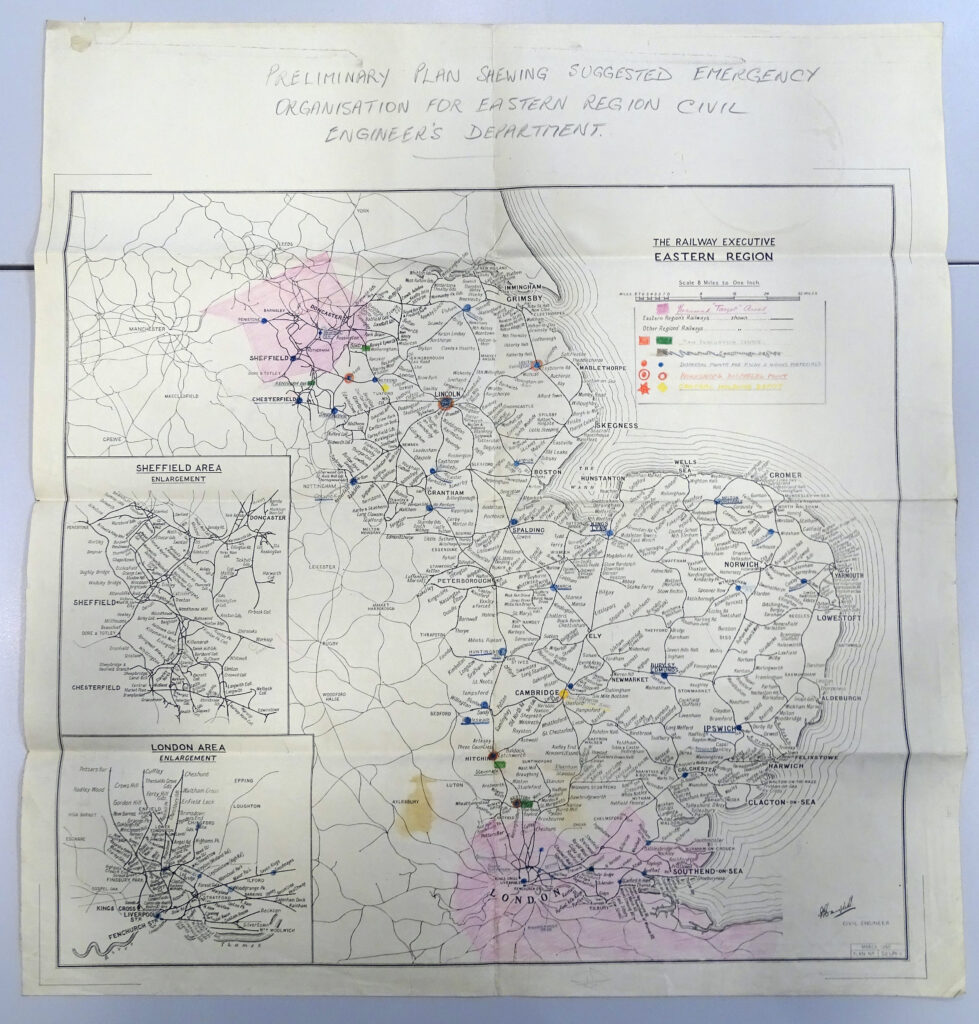

This article will specifically address the discussions and actions taken by the Civil defence officials of the Eastern Region of Britain’s railways housed at King’s Cross Station in the centre of London. The research presented here comes predominantly from the Civil Defence (CIVE) archive held in the collections of the National Railway Museum.[3] Aside from the British Transport Commission (BTC) records housed at the National Archives, it is perhaps the most detailed collection of railway civil defence work available. Using these documents, this article will lay out the purpose of the railways in Britain’s civil defence programme, followed by the measures that were planned and those that were actually undertaken before and after the advent of the hydrogen bomb. Finally, it will address the ‘culture’ of railway civil defence, arguing that despite the fact that reliance on government funding and guidance hampered progress on some projects, many railway civil engineers and other staff members were heavily invested in the work and training they undertook and believed it to be worthwhile.

Post-war civil defence has so far received limited attention from historians and scholars. Existing literature includes a recent comprehensive edited collection of civil defence across Western Europe, centred on imaginaries of nuclear disaster, which adds a variety of new perspectives from gender history to technical (Cronqvist, Farbøl and Sylvest (eds), 2021). Matthew Grant’s After the Bomb (2009) is, at the time of writing, the only full academic monograph on the British history of post-war civil defence. Alongside this, there are still only a fairly small number of academic articles,[4] as well as a recent popular history book by Taras Young (2019). Peter Hennessey’s Secret State (2010) and his most recent book, Winds of Change (2020), also nod to the subject. The majority of this available literature focuses on top-level government policy and decision making over civil defence issues.

Perhaps due to its stark nature, the 1955 Strath Report, an exercise in disaster planning which recognised how deeply catastrophic a hydrogen bomb attack on the UK would be, has achieved the most scholarly attention within the small area of British post-war civil defence scholarship. In contrast infrastructure history during the Cold War has generally received very limited attention.[5] Wayne Cocroft has argued that Britain’s Cold War ‘architectural legacy…is…as poorly understood as any prehistoric monument’.[6] In comparison, there is a slightly larger body of literature on US Cold War infrastructure, with particular attention paid to the significantly larger fallout shelter building programme which existed on the other side of the Atlantic.[7] For example, while they had initially been considered too expensive (Rose, 2001, p 24), the provision of ‘mass fallout shelters’ was declared ‘an urgent priority’ in 1962 by US President John F Kennedy (Brown, 1988, p 88), although after the subsidence of nuclear tension following the Cuban Missile Crisis, popular concern for fallout shelters collapsed (Rose, 2001, pp 10–11). Wayne Cocroft and Roger Thomas (2003, pp 226–227) briefly discuss railway civil defence in their book on Cold War infrastructure and make the assertion that the emergency control shelter scheme was primarily for evacuation purposes. This article therefore aims to make a small contribution to the history of Britain’s Cold War infrastructure in the context of the railways and the civil engineers who undertook their civil defence preparations.

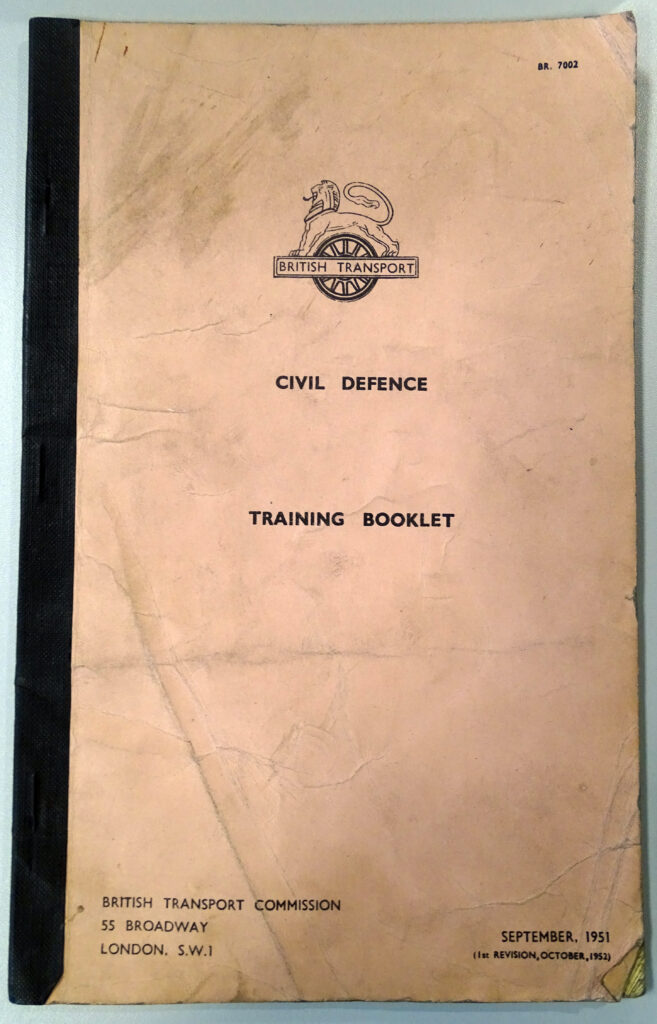

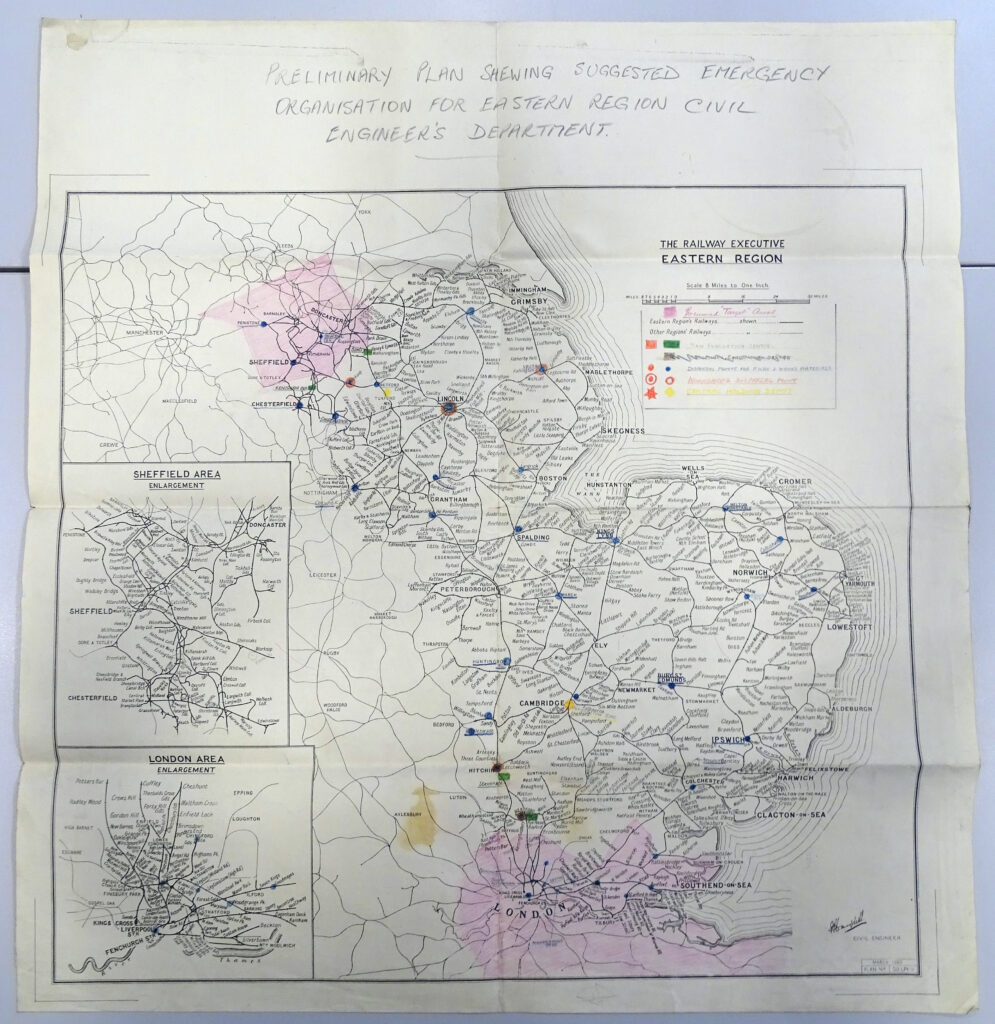

The railways’ civil defence planning was largely centralised in a small number of committees, the principle one being the Railway Executive ‘Due Functioning’ Committee and the BTC’s Civil Defence Committee, both of which included representatives from each branch of Britain’s railways and often a representative of their civil engineers.[8] Detailed planning was therefore undertaken within the nationalised industry by experts on railway infrastructure, without any direct involvement of government representatives or experts on the nuclear threat. While planning may have been centralised through these committees, implementation was left to the civil engineering section of each branch of the Railway Executive. Each would designate civil defence officers from their civil engineering departments to direct the infrastructure programmes and task some of their Inspectors to act as civil defence instructors. Eventually, each station, depot and office was required to have a small trained civil defence section. Aside from a few dedicated officers, all would hold another full-time role, but they would be expected to put their training into action in time of an emergency.

The purpose of railway civil defence

The central role that the railways would play in civil defence evolved as the bomb threat itself changed and the understanding of the impact and aftermath of such weaponry grew. Initially, it was believed that the railways would play a considerable role in evacuating civilians before a blast, followed by emergency repair work, and the haulage of essential supplies for both military and civilian use. However, following the successful test of the British hydrogen bomb in 1956, civil defence measures increasingly focused on planning and preparing for just the repair and haulage work, with a heavy focus on assisting the military or whichever local government structures survived. The unthinkable amount of destruction which could be caused across the British Isles with just a small number of warheads reduced the emphasis on evacuation as many viewed it as hopeless. This change in attitude impacted civil defence planning.

In 1953, a simulation of a nuclear attack on a working model of an imaginary town called Westhampton took place at the Hertfordshire Civil Defence Technical School and was attended by the Home Secretary, David Maxwell-Fyfe. According to reporting, ‘particular attention [was] paid to rail and road communications in order to simulate the sort of problems that might arise with large-scale evacuation from London after an atomic attack’.[9] The role of transport, rail included, was of fundamental importance to civil defence planning in the early 1950s. Firstly for the provision of evacuation out of key target areas should adequate warning of an attack be given, and then for the transport of rescue and repair workers, vital materials, and in support of the military. In a subsequent speech, Maxwell-Fyfe described civil defence as a ‘permanent’ part of the defences of the country.[10]

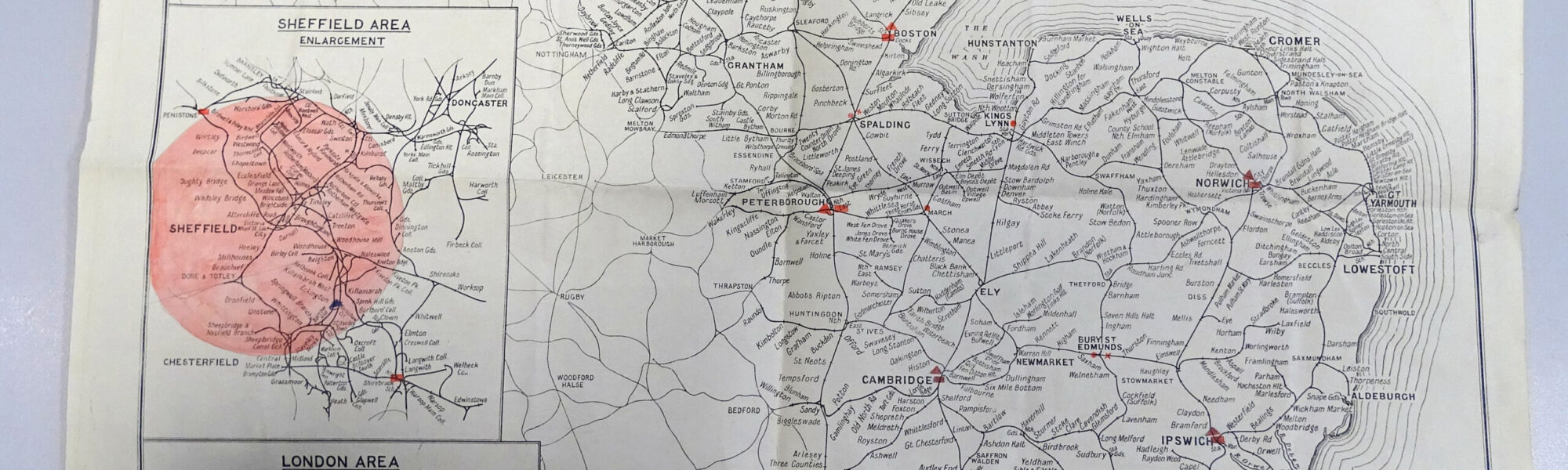

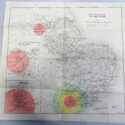

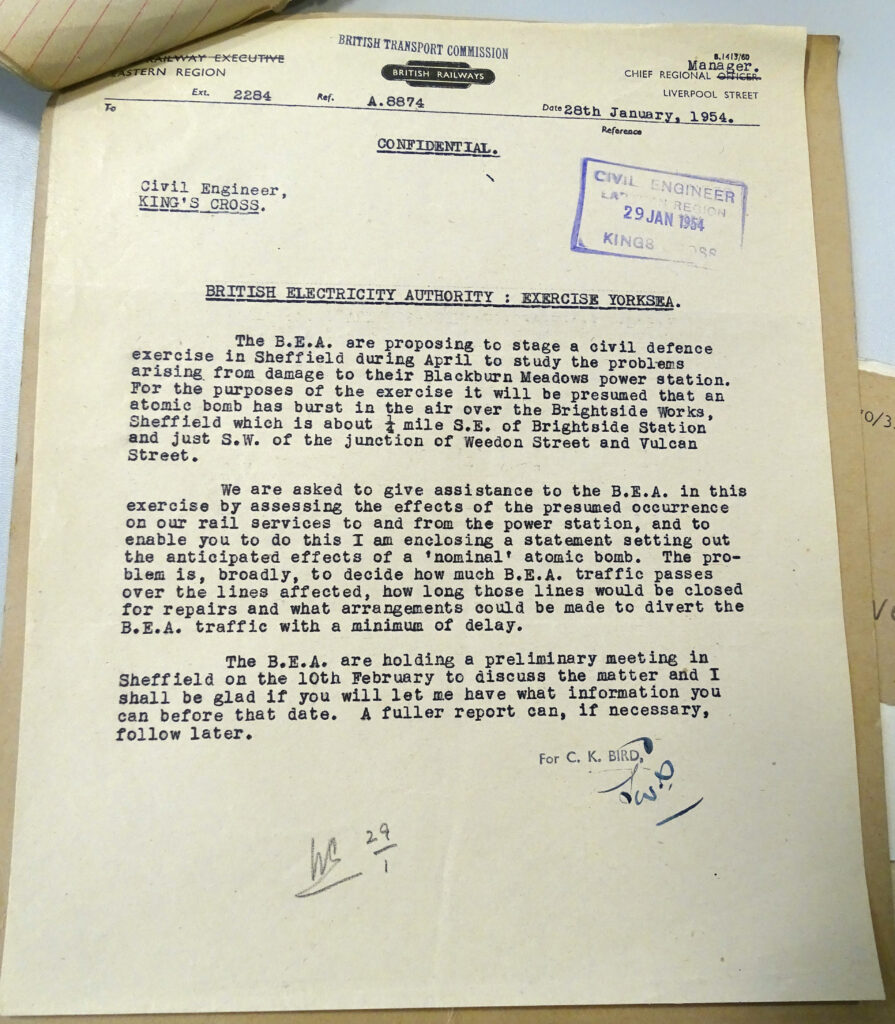

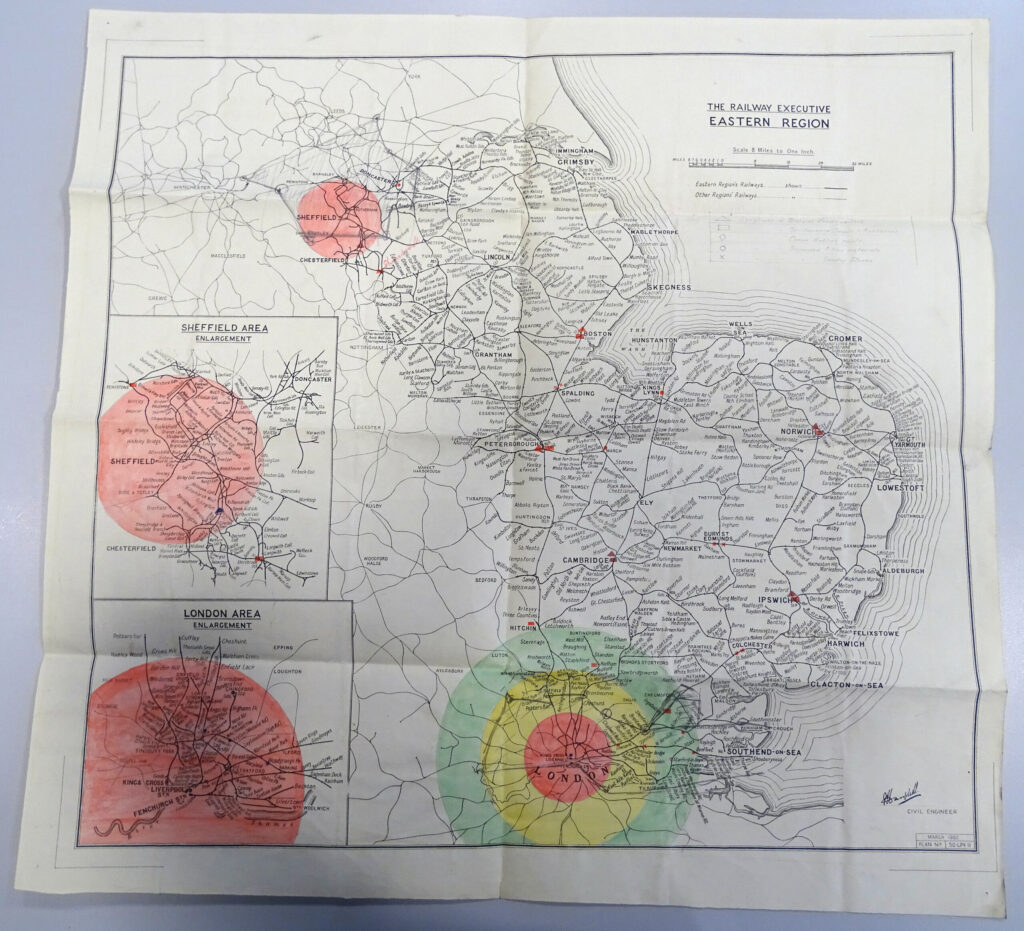

While the British government was setting out plans for the evacuation of school children and pregnant civilians from target areas, the nationalised industries were undertaking their own experiments to inform planning.[11] The British Electricity Authority’s Exercise ‘Yorksea’ consulted British Railways over the continued transportation of coal to power stations should an atomic weapon be dropped on Sheffield.[12] A report on the exercise attempted to identify the railway lines that would be damaged. Therefore, plans could focus on which lines were expected to need repairs, then provide estimations of repair time and clearance of debris. It was concluded that four to five days would be needed for the repair and clearance work to allow the passage of urgent trains.[13]

In a meeting of District Engineers from across the Eastern Region held on 15 April 1953, it was pointed out that in a National Emergency, the principle duty of railway workers in their department would be to repair infrastructure and rolling stock. As railways were a fundamental mode of transport, it would be of vital importance that they would continue to function. Railway workers therefore required training in the damage caused by high explosives, and increasingly atomic bombs, simply in order to ‘preserve their own lives’ in the aftermath of an attack.[14] This focus on repair only strengthened as the bomb threat grew.

Mass evacuations, while contemplated by government, were not the main focus of the civil defence planning of the railways themselves. Increasingly, civil defence plans assumed evacuation could only occur before a nuclear attack and that afterwards people ought to stay where they were and await guidance. Much of the discussion surrounding civil defence and the railways focused on the transportation of essential goods, both civilian and military, rather than the movement of people, following a possible attack. The railways during the early post-war years were still a principal mode of haulage, as well as transportation. The July 1961 Home Office annual report on civil defence activities asserted that civil defence preparations were vital ‘to ensure that available resources could be co-ordinated and deployed in the battle for survival which would follow a nuclear attack on this country’.[15] The report posited that maintaining the railways was a central aim of current government planning due to their importance to national transport links.[16]

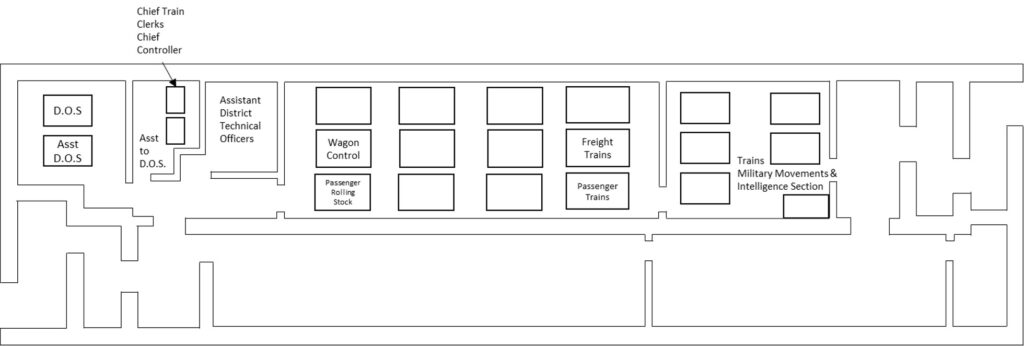

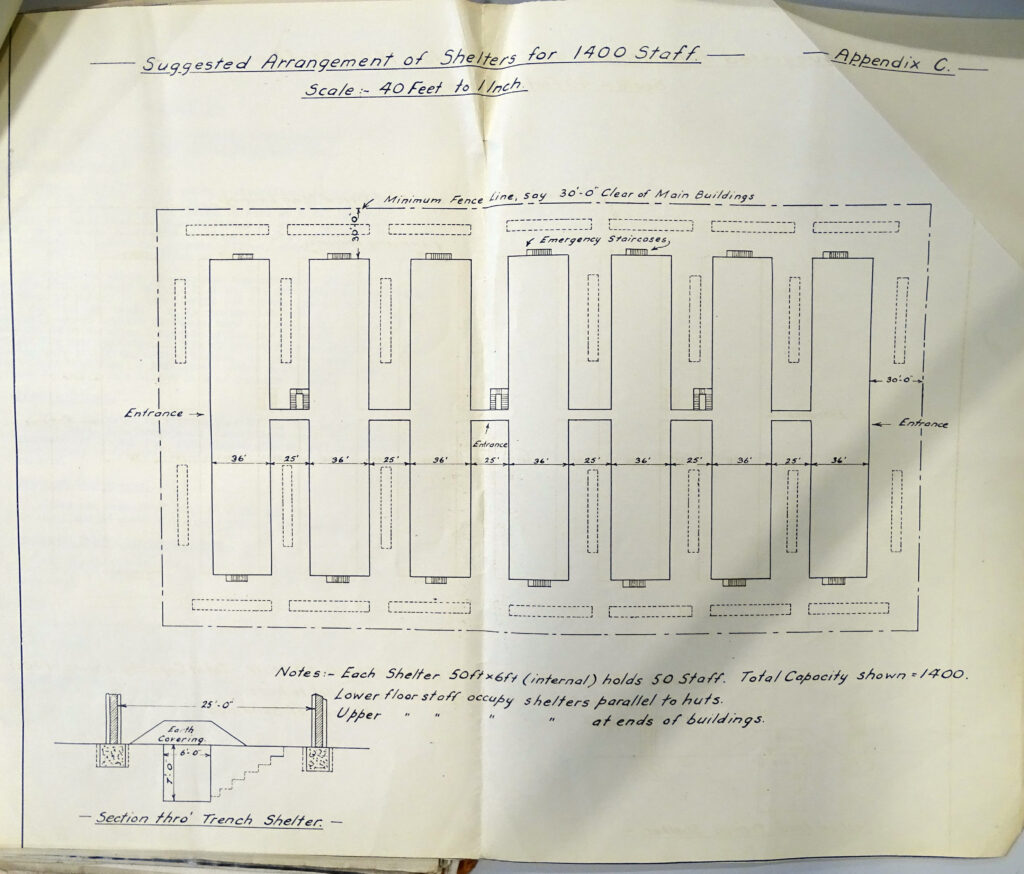

The emergency control shelter project was one of the largest undertakings of the railway civil defence programme. Designed to allow staff some degree of protection against an explosive or nuclear blast (at a distance) and radioactive fallout, these concrete structures would allow locomotives to complete any last-minute evacuations. Based on the technical diagrams of the emergency control shelters that were built and the discussion surrounding their development, this was not just for evacuation of civilians, but also military movement and the evacuation of plant as well as the locomotives themselves.[17] There was space dedicated to military movements in each control shelter, which suggests that railway usage would be linked with military operations and logistics, alongside the civil evacuation programmes.[18] The shelters were kitted with telecommunications equipment, but were not designed to house staff members except through the immediate aftermath of a blast if absolutely necessary: there was no designated living or sleeping space and proper toilets would be situated outside.[19] Home Office civil defence guides stated that most evacuation would be done ahead of any blasts in the weeks and months of international tension that would precede a nuclear attack.[20] Instead, the civil defence preparations undertaken by the railways were largely designed to allow the railways to rapidly get running again after an attack: evacuation would only be the first stage of Civil Defence plans put into action.[21] The very existence of the emergency control shelter project and their purpose was subject to a D-Notice, preventing newspapers from publishing information regarding them and restricting knowledge of their existence.[22]

Others outside of railway and Home Office circles still saw the former’s role in civil defence as heavily centred on evacuation and rightly noticed contradictions in civil defence messaging and the huge cutbacks made to Britain’s railways in the early 1960s. While debating the Transport Bill which would bring about the closure of smaller railway lines on the national network, known commonly as the ‘Beeching cuts’, [23] members of the House of Lords used a previous government statement on civil defence and evacuation to attack this dismantling of the railways.[24] Lord Lindgren, in the House of Lords debate on the Transport Bill on 8 May 1962, pointed out that the government had only a month previous stated that in the event of war, ten million people would need to be evacuated from London. Lingren argued that ‘you could not carry 10 million people on the roads of this country’ and asked the government if they did not see any ‘social’ or ‘defence value’ in the current railway system.[25] The cuts, of course, went ahead nonetheless.

By autumn 1963, a Home Office memorandum was circulated which noted that railway civil defence planning need not be abandoned as a result of the ‘Beeching cuts’. It stated that:

although major changes in the planned transport arrangements will be necessary in some areas, it seems clear that the implementation of the Beeching plan would not necessitate the abandonment of dispersal planning in broadly its present form, nor lead to any untoward delay in the preparation of the scheme.[26]

The memorandum ended on a sombre note:

Civil defence could not prevent very heavy casualties and enormous damage, but it could help men, women and children to survive and reduce their suffering. It is thus an essentially humanitarian work to which anyone may be proud to contribute.[27]

This same message was being communicated publicly by the Home Office, as well as to the Railway Executive. An official recruitment drive for civil defence volunteers publicly stated in national newspapers that civil defence could not prevent enormous destruction or loss of life and that it was ‘not intended to do so’.[28] Instead, civil defence was described as ‘a humanitarian operation’ to limit loss of life where possible and to help re-establish order and civility in the aftermath of an attack.[29] This public statement was reiterated in an internal memorandum distributed to the nationalised industries amongst other civil defence authorities.[30] It went on to state that, as the impact of new and developing nuclear weaponry was understood, ‘it is now seen that the survival period which would follow the lifesaving phase might be long and would certainly be grim’.[31] The railways would therefore be part of not just initial lifesaving and rescue operations, but also part of ‘a system which could function effectively in the much longer period during which all the governmental resources of the country would have to be used to their utmost to enable the nation to survive’.[32]

Therefore, the purpose of railway civil defence and the concept of what civil defence really was changed over time and was linked to the concurrent understanding of the bomb threat. The focus on evacuation planning decreased significantly by the 1960s, as the role of British civil defence switched from the initial ‘lifesaving phase’, getting people out of target zones, to the following ‘survival phase’ (the first few days or weeks after a bomb was dropped in which human survival following a nuclear attack would be the overriding goal), during which it was anticipated that the entire existence of the state would be threatened (Grant, 2009, p 5). The closure of thousands of kilometres of railway lines under the ‘Beeching cuts’ did not lead to a complete revision of railway civil defence planning, as evacuation was only ever envisaged before an attack, should any warning be given. Instead, internal discussions focused almost entirely on how to get railway lines repaired following an attack to begin the haulage of essential supplies and the assistance of military movements.

Railway civil defence before the H-bomb

Initially, civil defence planning in the immediate post-war period by the railways was based predominantly on the previous war: high levels of explosive attack with perhaps the use of a single atomic bomb. Of course, the redundancy of this work was later realised, due to the continuing development of nuclear weaponry as the Cold War intensified. However, the civil engineers tasked with planning and actioning civil defence measures on the railways were shackled to the limited guidance passed down from the British government and struggled to conceive of innovations to combat weaponry that even Britain’s top-most government employed scientists were working to understand (Smith, 2010).

In June 1946, the Home Office held several courses on civil defence to which Railway Civil Defence Officers were invited. However, the courses were aimed predominantly at local authorities and Railway Civil Defence Officers felt that the training ‘did not touch upon the problems with which the transport industry was faced, or, in the future, would be faced’.[33] Railway civil engineers looked for guidance elsewhere and in particular by exploring the experience of war in mainland Europe – in Germany especially. Working alongside Sir John Hodsoll, the Inspector General of Civil Defence at the Home Office, a small number of British Railway officials visited Germany and Belgium in November 1947 to identify how these countries had dealt with the extensive bombing campaigns inflicted upon them by the Allies during the war from a transportation perspective.

While in Germany, the three representatives of British Railways and the member of the Railway Research Service were guided by the directors and staff of the British Railway Control Teams of the Control Commission for Germany, and observed the ‘vast material and physical damage, far beyond all conception, wrought by the effect of modern warfare on the many towns and cities’.[34] The report, authored by J L Webster, the BTC Civil Defence Officer, and C E Whitworth of the Railway Research Service, described the ‘profound impression’ that the visit left upon the visitors. Over the course of the visit, the report claims they had analysed over 2,000 miles of track and greatly sympathised with the people they met over the destruction they saw.

The report did not make any specific actionable recommendations, stating that this would be dependent on national policy taken at a much higher level. However, they did give a number of recommendations for conversations they believed ought to begin immediately. First between the railways and the government to identify requirements of railway civil defence, and second with the military so that the railways could adequately plan for assisting operations during any future conflict. Other recommendations were largely technical and made suggestions about changes or additions to infrastructure based upon the measures implemented in Germany during the Second World War. The emergency control shelters (mobile and static) appear to have been based in part on the number of technical drawings obtained by the visitors while in Germany.[35] The small group came away convinced that long-term planning was absolutely vital to adequate civil defence, advocating for the ‘immediate establishment of a nucleus of key personnel fully trained in the latest technique in all aspects of civil defence’.[36]

Despite the urgency of the report, railway civil defence planning took a while to get moving. Even five years later, the BTC was criticised in the press for being a ‘slow starter’ with regards to planning.[37] However, this was not necessarily the fault of the railways. At a meeting of the Civil Defence Committee of the Eastern Region back in October 1949, they noted that the BTC and Railway Executive Civil Defence Committees had been established in December 1948 in accordance with the Civil Defence Act (1948).[38] Each Region employed a Civil Defence Officer and four part-time civil defence instructors. The meeting of the Eastern Region’s Civil Defence Committee was hopeful that, in light of Soviet Russia’s recent acquisition of the atomic bomb, the ‘tempo’ of planning would increase.[39] However, by August 1950, there had been little guidance from the British government.

Reacting to this lack of guidance, ‘a skeleton plan’ for local civil defence schemes was established across the Regions, to be implemented as soon as permission from the Home Office was granted.[40] Final drafts of these proposed civil defence organisations were requested from across the Eastern Region in April 1951.[41] However, it was not until October that year that the government contemplated how any funding would be made available for these schemes.[42] Meanwhile, by December 1951, the Eastern Region civil defence planners were beginning to lay down specifics. They were hoping to identify the locations of decentralised headquarters, moving essential staff outside of potential target zones, and begin plans for emergency stockpiling materials. Training for Railway Emergency Repair Squads, specially chosen repair workers who would be called upon in the event of bombing on British soil, was laid out and cataloguing of their supplies was also being clarified. Equipment for Emergency Workshop vehicles, to be used by the Squads, was being detailed also and, following guidance from the Ministry of Works, protections for signal boxes and pre-existing air raid shelters were ready to begin.

As rearmament of the British military was initiated in the early 1950s, the War Office required the repair of the rail depots and sidings that had fallen into disrepair and the construction of new facilities, such as supply depots.[43] In December 1951 planning for equipment stockpiling was discussed with retired Quartermaster-General to the British Armed Forces and now a member of the board of the BTC, General Sir Daril Watson. During the meeting, it was noted that in 1950 the consideration of atomic attack had been ‘expressly excluded’, but it was now an important aspect of planning going ahead.[44] This was one of the first occasions that atomic attack was to be addressed in planning.

However, there was still a small amount of push back on the need to plan for atomic attack by Eastern Region’s civil engineering department. A K Terris, Assistant Civil Engineer for the Eastern Region, wrote to J I Campbell, Civil Engineer for Eastern, on the subject of planning for atomic weapons damage. Terris wrote that, should there ever be an atomic attack, there would be so little use of traffic in the immediate aftermath that planning for the protection of staff and stockpiling of maintenance materials was useless, and that planning for atomic attack went ‘beyond the scope of Regional Engineers’.[45] In response, Campbell wrote that if guidance was provided by the British government and standards of necessary protection spelled out, then estimates of costs and timescales could be come to.[46] However, by February, no higher instruction had appeared and further organisation faltered.

Despite the Civil Engineering Department’s claim that they were floundering while waiting for official guidance, it was stated that ‘the Government and the Railway Executive require civil defence work to take priority over all other considerations (except essential maintenance work, of course)’.[47] At a following Due Function meeting, the Committee, now frustrated that planning was still based largely on the previous war, agreed to ask for a ‘more realistic’ concept of what they were planning for.[48] The Committee noted that they ‘appreciated that Civil Defence against atomic bombing involved far-reaching policy’, yet it recognised that to prepare for anything less than atomic warfare would make their efforts obsolete.[49]

Finally, in late December 1952, guidance on the civil defence schemes’ roll out was distributed by the government. In a handwritten note, A S Young, a member of the Chief Regional Office at Liverpool Street Station and of the Executive’s Civil Defence Committee, commented, ‘This is what we have waited so long for’.[50] The broader Industrial Civil Defence organisation was also finally established by the Home Office, giving British industrial workers an opportunity to organise and train.

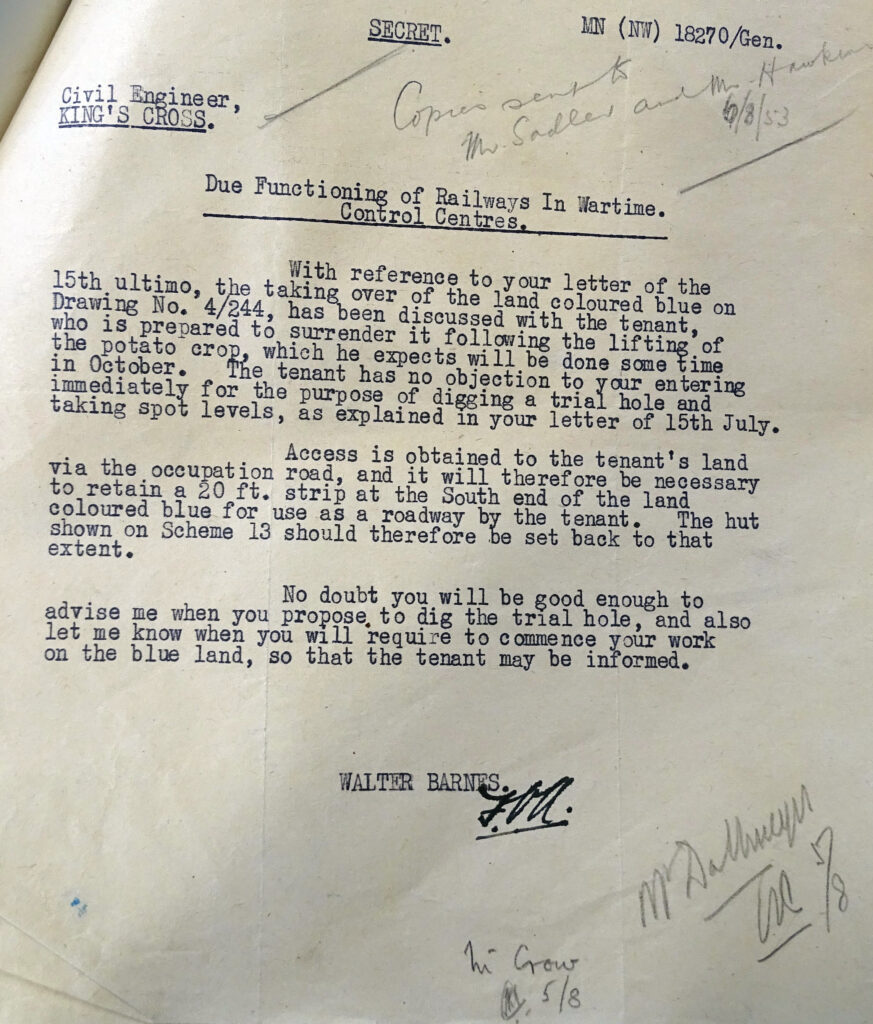

This momentum did not last long, however. In February 1953, the Ministry of Transport notified the BTC that there were still only very limited resources available, and that most of these would be directed into ‘active defence measures and to measures undertaken by civil departments in direct support of the Armed Forces’. Of the civil defence planning which the railways and other public utilities had undertaken, ‘no more than a small start [could] be made’.[51] Across the public utilities, the government made £1.7 million available for Due Functioning purposes, largely to be spent on a new flood gate system for the London Underground. A small amount was provided for work on some emergency control centres, the decentralisation of staff, and updates to lighting to improve blackout provision. Despite this setback, Eastern Region Civil Engineers still ‘stressed the urgency of Civil Defence work’.[52] Divided amongst the Regions, Eastern’s proposed expenditure for 1954/55 would be £165,000.[53] With this limited funding now available, the Due Functioning Committee ceased meeting as the small civil defence offices of each Region got to work on the plans that had been laid out. By the end of 1953, the Civil Defence section of Eastern would be placed in its own office as a ‘properly constituted separate unit of the Civil Engineer’s organisation’.[54]

While some of this money was made available, during the debate on the 1954 Civil Defence (Transport) Regulations in the House of Lords, the Ministry of Transport was criticised by members for taking so long. One participant in the debate rightly pointed out that the railways had been drawing up plans since 1950, but had been unable to finance them.[55] It was admitted that while the railways had been promised £1.2 million in 1953/54, they had only succeeded in spending £600,000.[56] The Civil Defence Regulations stated that while all the funding for the railways would be paid for by the government, the railways were required to submit regular progress reports to the Minister.[57] It was stipulated that if the BTC went over budget then it was liable for the costs, but if they were within budget, they could keep the surplus. This was likely designed to keep civil defence measures cost effective, but it also, perhaps unintentionally, encouraged the railways, which were struggling financially, to do the bare minimum.

Civil defence measures did not ever become an overinflated aspect of the work of the Eastern Region civil engineering office. In July 1954, the suggestion was made to reduce the number of their civil defence instructors from four to three.[58] Their instructors at the time were all over 49 years old and holding other full-time positions on top of their instructing work. However, it does not appear that this cut back ever took place. Over a year later, when discussing the formation of Industrial Civil Defence Units within Eastern in November 1955, C K Bird, the Chief Regional Officer for Eastern, still had four instructors.[59]

Paralysis: railway civil defence in light of the H-bomb

From its inception, top secret discussions within the highest level of British government had begun to establish how destructive a thermonuclear war would be for Britain. The 1955 Strath Report bleakly advised that it would take only ten hydrogen bombs to wipe out the majority of the population and leave the rest in total chaos, and thus cause the complete breakdown of the state (Hughes, 2003, p 263). This led the government’s Home Defence Committee to advise that any measures specifically for any war fought with only conventional and atomic weaponry should be ‘discontinued’ in light of the Soviet threat, and that major civil defence initiatives capable of protection against thermonuclear weapons should be pursued despite the enormous cost.[60] Instead, a fluctuating commitment to funding problematised further planning until civil defence in Britain declined entirely.

In April 1956, after hearing that more guidance might be being made available on the latest thinking on future warfare and the role of civil defence, the suggestion was made to re-establish the Committee on Due Functioning which had not met since 1952. The BTC in January 1956 had been contemplating a five-year plan that was fully costed to provide for the strengthening of infrastructure, decentralisation and accommodation of key personnel, shelter building and emergency repair depots, and air-raid warning and central switching of lighting – all factors which had been identified as necessary for adequate civil defence planning over five years prior.[61]

By 1956, planning assumed that following a nuclear attack (but not yet a thermonuclear one), civil defence and military forces would first assess the damage done and likelihood of repair. Rail authorities would then cooperate with road authorities to prioritise repair work in different areas and on different routes. The Due Functioning Committee therefore set out that, within each Region, much smaller areas needed to be ‘self-supporting for [repair] materials’, on the assumption that fuel would be limited, and repair work would need to draw on manual labour. Some vehicles were fitted with living, office and administrative spaces ‘as a means of prosecuting work as the restoration railhead advances’.[62] The working assumption at this time was that any threat of radiation would last only a few days, after which time repair could get underway.

In light of the growing destructivity of nuclear weaponry, it was assumed by the railways that they would need to be maintained ‘as expeditiously as possible’ for the movement of vital supplies, both military and essential.[63] It was only in 1956 that the Eastern Region’s Civil Engineering Department finally admitted that previous planning on the basis of the Second World War had been wrong, and that the railways had gone above and beyond this guidance from the government at times in their civil defence planning. C W King, the Chief Civil Engineer of the BTC, wrote to the District Chief Civil Engineers:

some of us may have had doubts about the rightness of planning on this basis [that of the previous war], but the need for and the location of control centres and other features of the plan have probably been considered in relation to this concept in the absence of better advice.[64]

By July 1956, the promised finances from the Ministry of Transport were once again not forthcoming, and the planning which had begun in January was scaled back. Priority was placed on only the partial construction of emergency control shelters by the BTC (Railways) Civil Defence Committee.[65] While the first return meeting of Due Functioning was still held on 18 July, the discussion focused on a request from Ministry of Transport about whether railway tunnels could potentially be used as large fall-out shelters.[66] However, the idea was quickly discounted due to the difficulty of temporarily blocking up the entrances to provide enough protection, ventilation and lighting, while leaving the tunnel in a useable state when required for use again following the initial survival phase.

The successful ‘Grapple X’ test of the British hydrogen bomb on Christmas Island in 1957 led to another major paralysis and redefinition of civil defence planning. It was suddenly acutely felt by the public and by those responsible for the railways’ civil defence that, with the development of the British hydrogen bomb, any future nuclear war had become a lot more destructive and a lot more deadly. There had already been some popular concern after the US’s Castle-Bravo test in 1954, which caused Coventry City Council to abandon its civil defence planning (Barnett, 2015, p 278). British civil defence at the top level was no longer viewed as a viable ‘insurance policy’ and wildly expensive plans for public shelters for example were rejected in favour of funding ‘active’ defence measures, such as the British thermonuclear weapons programme (Smith, 2009, p 61). A policy of promoting public confidence in inexpensive measures was adopted in place of the ‘insurance policy’ and convincing people that civil defence would work became more important than making it actually do so. Public messaging and voluntary involvement became paramount (Smith, 2009, p 62). This was a campaign designed to alleviate fears and build confidence, despite some beliefs that the 1957 Defence White Paper included the accidental admittance of the superfluousness of civil defence now that Britain was committed to deterrence through thermonuclear capability (Laucht, 2016, p 232).

When the news hit of the successful test of the UK’s own thermonuclear device, the railways’ planning, which had just had another burst of energy, was paused once again and became subject to high-level discussion. With discussions going all the way up to Cabinet level, the railways’ plans, such as the decentralisation of staff, were put on hold awaiting guidance. Railway civil defence planners were told that the Ministry of Transport & Civil Aviation would be considering whether their work should even continue.[67] In the same notice to the Regional Civil Engineering Departments, it was added that reduction in funding was likely to go ahead and, with the advent of guided missiles, work on lighting and the provision of blackouts was permanently halted as it would no longer be of any use.

It took another year for some planning activities to be picked up again. In March 1958, a major survey of the protective factor of the railways’ buildings was put underway by the BTC after a suggestion was made by the Secretary of State for Transport to identify which were of any use, which needed some maintenance, and which could be improved through measures such as sandbagging.[68] Worried that this survey would be a significant amount of work and would take staff away from vital modernisation projects, C W King, Chief Civil Engineer of the BTC, agreed that the remaining Civil Defence Officers in each Region should look to establish ‘the magnitude of the work which would be involved’.[69]

By the late 1950s, the Home Office described a new outlook, with ‘a better balanced and realistic civil defence programme’, which from the railways’ perspective mostly referred to regular updates communicated by the Home Office in bulletins to national civil defence programmes.[70] Studies and policy were to be regularly communicated down to ‘frontline’ civil defence workers and volunteers, which the government hoped would act as voices of authority and allow the reestablishment of state control following a nuclear attack.[71] The Home Office also spread news of exercises to the national industries, such as Operation Cloud Dragon, which was a NATO exercise simulating a nuclear attack in which over 8,000 Royal Observer Corps volunteers from across the UK took part.[72]

These new bulletins, while improving communication and awareness of the latest thinking and developments on civil defence, did not solve the lack of funding. At a joint meeting of the Fire and Civil Defence (Railways) Committees of the BTC, it was raised that the bulletins had ‘no compulsory powers but simply gave guidance on the measures to be taken against the serious risk of fire resulting from nuclear warfare’.[73] The scheme proposed in the latest bulletin would cost over £9 million for the 382 fully equipped Fire Guard Sections that it suggested adding to the existing civil defence sections. No financial assistance, however, would be made available for this significant undertaking, which made this scheme ‘impracticable’ for the railways.[74] The joint meeting pointed out that other large industrial groups had come to the same conclusion as they had done. Therefore, while top-down advice and decision-making was more forthcoming by the early 1960s, civil defence preparations were no less reliant on government funding to back the advice.

What funding was available fluctuated significantly during the early 1960s, with £15 million total spending made on civil defence measures and programmes in 1960/61 decreasing to £10 million in 1961/62. Funding promised for 1963/64 rose dramatically to £23 million, most likely as a result of escalation of nuclear tension experienced during late 1962.[75] Until 1961, the construction of the emergency control shelters had been a major focus of the railway’s efforts, but moving forward, the government was only making £500,000 available to last until 31 March 1965 for these sorts of measures.[76] Furthermore, based on the guidelines for this funding, the railway control shelters that were being constructed would not even necessarily qualify for reimbursement. The vast majority of planned control shelters had only their foundations built – with the assumption being that if global tensions rose then the funding would become available to fully complete and kit out the shelters. However, the new guidelines stated that full funding would be awarded only to measures that could be put to use should a warning of seven days be given for a potential nuclear attack. The civil engineers’ plan to half complete their control shelters meant that they would not be ready within this seven-day window and so the project as it stood did not qualify for full funding.

Only a very small number of the railway’s emergency control shelters had been built in full to test and improve the design. For example, the Eastern region completed their emergency control shelter for testing at Knebworth in October 1957.[77] Based on the reduced amount of funding and the Ministry’s insistence that measures ‘must be ready for use after seven days warning of imminent attack’, the static emergency control shelter planning, which had been central to the railways’ civil defence programmes for a decade, was now threating to become obsolete.[78]

The culture of railway civil defence

Despite the numerous setbacks for industrial Civil Defence Officers, there was a real sense of community and importance surrounding the work they were doing. The officers developed some shared beliefs, procedures and commitment to their work, all equating to what could be described as a shared culture. As argued by Jonathan Hogg (in Cronqvist, Farbøl and Sylvest (eds), 2021, p 78), civil defence training invited participants to engage in shared imaginaries of their work should a bomb be dropped and to develop a sense of hope for survival. The Civil Defence Officers of the railways were often long-serving figures who shared this hope, and were dedicated to their work, despite the constant hiccups, set-backs and revisions. J L Webster, the BTC’s Civil Defence Officer, held his position for over a decade, while A Crow, the Eastern region’s Civil Defence Officer, stayed in his role for over seven years. Crow died in 1963, still holding his position.[79]

Local authority civil defence and railway officers would share materials they found interesting and discuss the training courses they had undertaken.[80] The Civil Defence Officer for York Council, for example, made training facilities available for free for railway workers of the Northeast Region from February 1952.[81] Following the initial training event, over 300 workers in the York area and 100 from around Darlington showed interest in attending further courses. Describing his motivations, York’s Civil Defence officer wrote ‘our staffs would have to work very closely together in the unhappy event of war, and I feel that liaison of this kind in peace time will pave the way to a better understanding of our respective problems later’.[82] By October 1952, the scheme attracted 1,029 volunteers from the Northeast Region in the York. J L Webster, who had travelled to Germany on the initial investigation trip into transport civil defence, wrote back to York’s Civil Defence officer expressing thanks for the ‘tremendous help’ he had provided.[83] Similar invitations of training were extended to the Civil Defence staff of the Eastern Region, but these were declined in favour of BTC specific training that was to be provided at a dedicated school.[84]

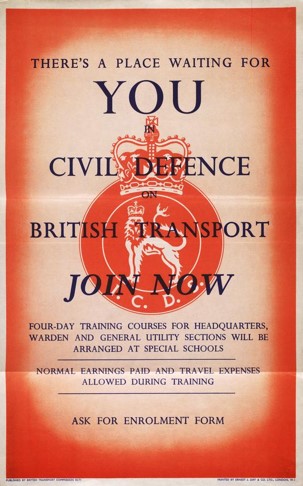

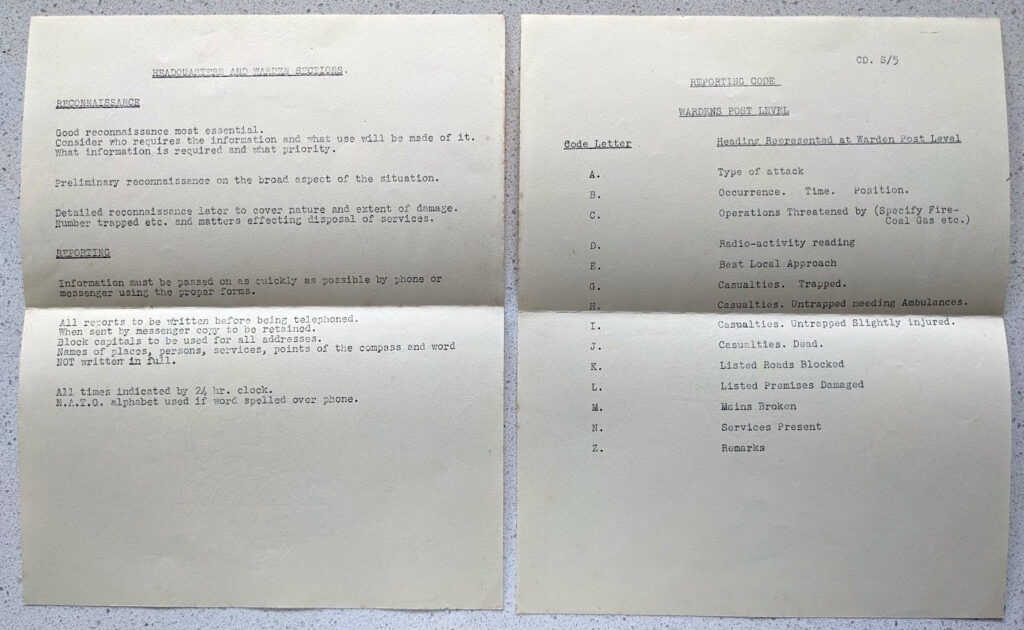

Volunteers were enlisted to train as Wardens, General Utility or Headquarters Civil Defence members.[85] C K Bird wrote ‘It is the wish of the Commission that these civil defence schemes shall be a success and I would ask you personally to ensure that every support is given to them, both in regard to the appeal for volunteers and in maintaining interest in the schemes subsequently’.[86] Training for each section would take each volunteer at least thirty hours to complete, with over three hours for each section dedicated just to the dangers of radiation and the use of radiac machines.[87]

This same degree of dedication and enterprise is also clear from the peacetime efforts of other civil defence workers and volunteers. Key examples of this, which were frequently referenced during the 1950s and into the 1960s, were the roles played by civil defence volunteers in the devastating floods on the East Coast, and the Harrow and Wealdstone railway disaster, both in 1952.[88] A Home Office annual report on civil defence activities praised the role that civil defence workers had played in further flooding during 1960.[89] A 1957 recruitment poster for the Civil Defence Corps referred to the role that civil defence officers played in these emergencies, as well as their role in the Lynmouth disaster, as another reason to join up.[90] The autumn 1963 recruitment drive drew directly on these characteristics and ended with the statement:

What you will be asked to do won’t always be easy. But it will be important. You will find interest, companionship, and the satisfaction of doing a vital job.[91]

Conclusion

As nuclear tension between the United States and the Soviet Union continued to decline into the late 1960s, following its pinnacle during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, the prevalence of civil defence and the provision of funding subsided almost completely. The surviving records of the Eastern region’s civil defence office end around 1963. In 1968, civil defence at the Home Office was wound up almost entirely (Grant, 2009, p 5). Duncan Campbell’s War Plan UK (1983, pp 272–273) included a small section on the state of railway civil defence as by 1982 after Cold War tensions had heightened once again. By this time, most of the measures, aside from the Emergency Control Shelter foundations, had been disbanded or deserted, and even the few Mobile Emergency Control engines that provided office and residential space in the train itself had been sold off in 1979 and 1980. Campbell (1983, p 273) described the transport situation of civil defence as ‘extremely gloomy’, pointing out that above all it would be the availability of fuel which would entirely dictate the utility of transport during and after a nuclear attack.

Thankfully, of course, the Cold War never escalated into the nuclear Armageddon that was feared. The efforts of civil defence workers and volunteers were therefore never needed in practice, and the British government’s policy increasingly centred on deterrence through the period of détente and throughout the return to increased tension with the Soviet Union during the 1980s. But if nuclear warfare had ever broken out, Britain would have been vastly underprepared. Railway civil defence officers had developed full plans for improved and protected infrastructure, stockpiling, and the recruiting and training volunteers in civil defence and the threat of nuclear weapons and radiation. However, they were hampered by a lack of government guidance on target zones or the type of bombs to prepare for, and by the inadequate funding for these schemes, leading to regular periods of paralysis and delay. Nevertheless, railway civil engineers working on civil defence saw real value in their work and remained dedicated to overseeing their plans for over a decade. Plans which might have helped to allow one of Britain’s vital modes of transport to continue to function should the worst imaginable come to pass.

The efforts of this small group of civil engineers demonstrates the difficulty of turning civil defence planning into reality. Beyond the distribution of guidance pamphlets and lectures on the dangers of radiation, for those at ‘the sharp end’ of Britain’s civil defence it was extremely difficult to actually design and build for a threat that was continuously growing and becoming even more terrible. This unsurprisingly led to the forced redundancy of much of Britain’s Cold War infrastructure, beyond that of the railways.[92] Once the threat became too large, as the number of warheads required to destroy Britain in its entirety became almost a single digit, the usefulness of concrete, structural steel, and mobile repair engines became as inconceivable as the warfare itself.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Dr Sophie Vohra for her invaluable input and guidance during the research and composition of this article. The author would also like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their extremely helpful comments on an earlier draft of this piece. This research was undertaken while the author was on a Research Employability Project placement at the National Railway Museum and in receipt of funding from the Arts and Humanities Research Council via the White Rose College of Arts and Humanities, Grant Number: AH/R012733/1.

Tags

Footnotes

discover-and-understand/military/cold-war/ (accessed 22 July 2023) Back to text