Issue 23 Editorial

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/252309

Abstract

Julia Knights reflects on Issue 23 of the Science Museum Group Journal.

Keywords

Editorial, exhibitions

Editorial

Welcome to the Spring 2025 edition of SMG’s journal.

As a soil and climate scientist, I am passionate about the role of research in our public programmes in tackling global challenges facing humanity, including the sixth mass extinction and climate change.

And in the run up to the most important international climate summit this year – COP30 in Belém in Brazil – and with two in five plants threatened globally with extinction, it feels timely to reflect on one of the Science Museum Group’s key priorities through our research, public programme and National Collection: sustainability and climate change.

The Science Museum has a long history of dealing with this pressing issue, whether through its pioneering Atmosphere gallery, our exhibitions or through acquisitions such as the James Lovelock archive.

In February 2020, we hosted the Prime Minister, who unveiled that Glasgow would host the COP26 climate summit the following year. On the same day, Sir David Attenborough planted trees with local school children in the Science Museum garden to celebrate this as well as the UK’s Decade of Climate Action. In April 2020, the Science Museum Group set ourselves a target of Net Zero by 2033 following the respected Science Based Targets Initiative in line with the Paris Agreement.

Ahead of COP26, we formed a partnership with the UK’s largest tree charity, The Woodland Trust, and have been planting a thousand native trees each year with them ever since, at our 545-acre Science and Innovation Park (SIP) in Wiltshire, adding to the 44,000 trees already established. This is also where we host one of the UK’s largest solar farms. Solar is among the technologies that features in our Energy Revolution gallery aimed at addressing how globally we could shift from a world powered by fossil fuels to one powered by low carbon technologies.

Meanwhile, last October, our new Hawking Building, which houses over 300,000 historic objects from our National Collection, was inaugurated at SIP in honour of the late Professor Stephen Hawking, whose office we have acquired through the UK Government’s Acceptance in Lieu scheme. The energy-efficient purpose-built Hawking Building (equivalent in size to over 600 double decker buses) boasts solar on the roof, insulated walls made of hempcrete and a biomass boiler to control the humidity. As well as public tours, researchers can now apply to visit and see a particular object from the collection, either virtually or in-person.

On display in the Hawking Building, our vast science and technology collection houses a fascinating array of objects representing human ingenuity, including those related to low and zero carbon technology such as the Hydrogen Fuel cell bus (2001–2006), a solar-powered pedalled and electric car (1981) and a Tramcar built for the Glasgow Corporation (1901), which served the people of Glasgow for 60 years.

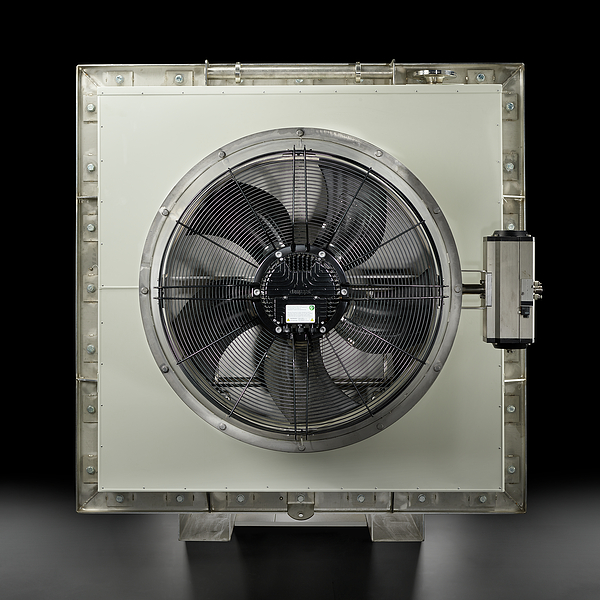

Collecting climate response innovations continues to be a curatorial priority, including the Climeworks carbon collector unit (2013) made in Switzerland. Designed to take eight kilograms of carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere per day, direct air capture technology such as this is considered by many scientists and governments to be part of a suite of vital technologies needed to help curb dangerous climate change.

Another gem in our collection is Klaus Lackner’s ‘artificial tree’, which is reported to be able to sequester carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere a thousand times faster than an average tree.

Both objects were on display during the Our Future Planet exhibition at the Science Museum in 2021.

Ahead of the COP30 in Brazil, SMG recently launched Vanishing Amazon – an online exhibition co-curated by SMG’s Science Director Roger Highfield and myself, to shine a light on how climate change has impacted the Brazilian Amazon rainforest. Some areas are close to a tipping point, beyond which the forest could become savannah. The exhibition also addresses how indigenous communities help safeguard one of the most biodiverse places on Earth. The exhibition features stunning images of three of these indigenous communities, captured in the 1990s by renowned photographer Mirella Ricciardi. Ricciardi was the inspiration for Sebastião Salgado’s project photographing indigenous communities in the Brazilian Amazon. His stunning exhibition celebrating Brazil’s Amazon rainforest, entitled Amazônia, was held at the Science Museum in London and the Science and Industry Museum in Manchester in 2022.

On 21 April we said goodbye to the Versailles: Science and Splendour exhibition at the Science Museum, which celebrated science at the court of Louis XIV, XV and XVI.

Plants equalled power on a global stage at Versailles. As such, our curators dedicated a whole room in the exhibition to celebrating the Bourbon French kings’ deep passion for the natural world. Here the exhibition highlighted the vast formal gardens commissioned by Louis XIV, and Louis XV’s deep passion for botany – including his botanical and kitchen gardens. Research was undertaken at Versailles on thousands of species brought from around the world as part of the emerging European field of plant classification fuelled by experts from the French Academy of Sciences founded by Louis XIV.

Notable objects on display included a painting entitled ‘Pineapple in a pot’ by Jean-Baptiste Oudry (1733) – illustrating the mastery of Louis XIV’s chief gardener, Jean-Baptiste de La Quintinie, who optimised light and heat conditions to enable imported crops such as pineapples and date palms to thrive in Versailles’s hothouses. Oudry’s painting was a portrait for the first pineapple to be successfully grown in continental France and was presented to then-King Louis XV on Christmas Day. The portrait would later hang in Marie Antoinette’s chambers in Versailles’s Petit Trianon.

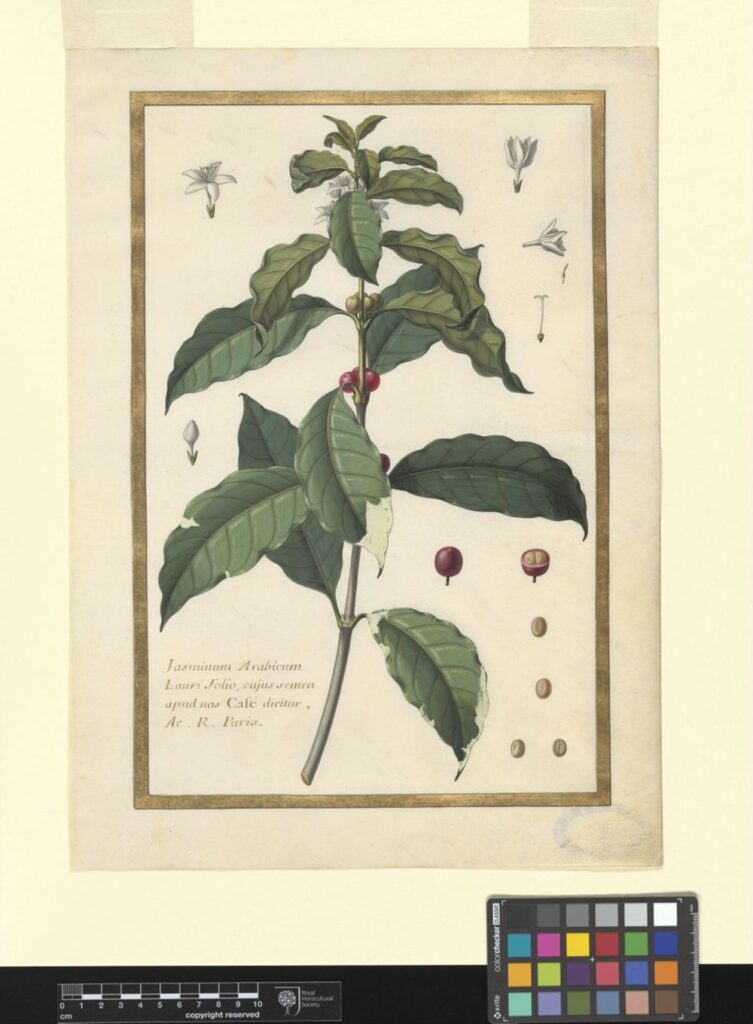

A watercolour of a coffee plant on display by Claude Aubriet, the official painter to Louis XIV and XV – lent by the Royal Horticultural Society Lindley Collections – revealed a fascinating economic botany story. It depicted a coffee plant given to Louis XIV in 1714 by the Dutch. In 1721, coffee, potentially originating from this actual plant, was taken to Martinique, France’s Caribbean colony, to be exploited as a crop.

The Telegraph and The Standard both gave our exhibition four-star reviews, with the former calling it ‘a masterclass in storytelling’. Following the launch, I hosted an academic conference at the museum, inviting academics from France, UK and beyond to debate how the French monarchy used science to elevate France’s influence and power on a global stage for military, medical, cultural and economic gain – and I’m delighted to see in this edition, a keynote paper by Colin Jones on the subject.

As I write, my colleagues are making the final touches to our next major free exhibition at the Science Museum related to sustainability, climate change and food security. Entitled Future of Food, it examines how to feed ten billion people by 2050 sustainably. Due to open on 24 July, visitors will be able to enjoy over a hundred objects on display. They tell remarkable stories about producing food sustainability, from growing meat from cells at home in Japan, to employing local radio to help control pests in Kenya, to using wild crop relatives of our cultivated crops from the Millenium seed bank at Wakehurst Place, Kew.

Research is one of the vital ways we uncover and share inspiring stories about science through our collections at SMG. As such, we have been welcoming a new cohort of PhD students recently, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) Collaborative Partnership Consortium. In total we have 33 PhD projects across SMG. Specifically on climate change, we have two projects: ‘The organic movement and the public culture of science 1985–2025’ led by Katie McNab with Nottingham University; and ‘Curating Climate Change: collecting and displaying ecological crisis in UK museums’ led by Dorothea Fox with the University of East Anglia. We are soon to recruit a researcher for ‘Unearthly ecologies: Exploring environmentalism and Sustainability beyond earth through literature and culture’ with Nottingham Trent University.

Our teams are working on a new gallery at the Science Museum entitled Tomorrow, which will focus on future innovations to solve humanity’s most pressing issues in the decades to come. Unsurprisingly, and sadly, innovations to tackle the climate emergency, nature loss and growing our food sustainably will be some of the key areas of focus which will extend beyond the lifetime of this new gallery.

Note from the Guest Editor

This issue was guest-edited by Medievalist scholar Diane Heath. She writes a short comment on the experience here.

It is a pleasure to present the Spring 2025 issue of the Science Museum Group Journal to you. Following publication of our tenth anniversary issue, which Ian Blatchford described as encouraging ‘generous, multidisciplinary conversations at times when we have been so exposed to division and polarisation’, this issue carries on the journal’s work of scientific and curatorial discourse and scholarship. For me this issue reveals wonder and innovation – from discussion of extraordinary objects from Versailles, to studies of the wonder our collections spark in visitors, to ideas and innovation in open access publishing, the scholarly work published here gives a glimpse of the sparkle and value that museum research brings.

My thanks to all our contributors and to General Editor Kate Steiner and production editor Lyz Bush-Peel. I hope you the reader find as much wonder and enjoyment in this Spring issue as I have had working with such terrific people.