Festschrift: experimenting with research: Kenneth Mees, Eastman Kodak and the challenges of diversification

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201311

Abstract

Early industrial research laboratories were closely tied to the needs of business, a point that emerges strikingly in the case of Eastman Kodak, where the principles laid down by George Eastman and Kenneth Mees before the First World War continued to govern research until well after the Second World War. But industrial research is also a gamble involving decisions over which projects should be pursued and which should be dropped. Ultimately Kodak evolved a conservative management culture, one that responded sluggishly to new opportunities and failed to adapt rapidly enough to market realities. In a classic case of the ‘innovator’s dilemma’, Kodak continued to bet on its dominance in an increasingly outmoded technology, with disastrous consequences.

Keywords

Carl Duisberg, Charles Edward Kenneth Mees, digital photography, Eastman Kodak Company, Eastman Kodak Research Laboratories, George Eastman, Industrial R&D, Polaroid, Robert Bud, silver halide photography, Xerox

Author's note

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201311/002This paper is based on a study undertaken in 1985 for the R&D Pioneers Conference at the Hagley Museum and Library in Wilmington, Delaware (see footnote 1), which has remained unpublished until now. I thank David Hounshell for the invitation to contribute to the conference and my fellow conferees and colleagues at the University of Pennsylvania for many informative and stimulating conversations about the history of industrial research.

None of those colleagues provoked my thinking more – then and since – than Robert F Bud, whom I first met in September 1973 when we were both neophyte graduate students in the Department of History & Sociology of Science at the University of Pennsylvania. Together with P Thomas Carroll, we shared offices and an education in the basement of Smith Hall during the years we worked together with our advisor and co-author Arnold Thackray on what became Chemistry in America, 1876–1976: Historical Indicators (Dordrecht: D Reidel, 1985). After Rob left for England in 1977 to take up his post at the Science Museum and an illustrious and productive career as a museum curator and scholar, we may not have conversed as regularly, but I continued to relish the opportunity to compare notes and share ideas with Rob whenever we met. We have remained interested in many of the same historical questions, but our careers have developed along different paths – his in a more scholarly direction, mine with a more practical focus (having left academe for the business world more than thirty years ago). Throughout our nearly fifty years of friendship, I’ve never known Rob not to be brimming with enthusiasm about a bright new idea he’s excited to get to the bottom of. He may have retired from the Science Museum, but I’m sure he’ll continue to remain active in writing and thinking about applied science – I look forward to seeing where his restless and creative mind takes him next!

Introduction: the historical context of Kodak research

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201311/003For much of the twentieth century, photography was synonymous with Kodak. George Eastman’s original vision was of making a camera that was as easy to use as a pencil. If his persistence in pursuing that ideal was responsible for establishing Kodak’s dominant position in the industry, then the contributions of Kodak’s research laboratories were largely responsible for maintaining that lead for the next 75 years. Set up in 1912, when Eastman hired a young English chemist, Charles Edward Kenneth Mees (1882–1960), to act as research director of the growing company based in Rochester, New York, the Kodak Research Laboratories quickly became a leading centre of photographic research. Mees’s laboratory was also one of the pioneering corporate research efforts in twentieth-century America. Like other pioneers of R&D, such as General Electric, Du Pont and AT&T, Kodak’s research laboratory was an adaptation of nineteenth-century antecedents, designed to serve the needs of corporate capital in the new century. The fact that all four of these laboratories remained among the top supporters of industrial research and development in America through succeeding decades of change and competition does pose an interesting set of historical questions.[1]

The history of industrial research has attracted a great deal of attention in recent years as more and more historians have come to appreciate its importance as a major element of the political economy of American science and technology. Kenneth Mees was certainly convinced of this. In a 1958 letter to historian Charles Singer congratulating him on the appearance of A History of Technology (published by the Oxford University Press), Mees observed that ‘it is a wonderful and monumental work…[and] much more useful than Sarton’s delving in Arabic manuscripts. I always feel that the part of history that is really important is the modern history. This is particularly true in the case of science. It doesn’t really matter very much what some Greek thought because his ideas were promptly forgotten, but the history of the development of industrial research, for instance, which is so new that it has not yet been written, is of the greatest importance.’ He then suggested that Singer follow up his history of technology with a study of the application of science to industry since 1900, a development that by 1950 had ‘changed the whole organization of American industry’ and become its most ‘characteristic feature’.[2]

Historians since Singer have taken up Mees’s call. David A Hounshell has provided an able and perceptive review of the origins of modern industrial research in America.[3] Several themes in the literature are pertinent to the Kodak case. The first generation of work in this area pointed to the confluence of several economic, organisational and technical factors in explaining the rise of industrial research at the turn of the century. Changes in business organisation created companies with the capital resources to invest in long-range research, and managers interested in maintaining their strategic position. On the supply side, American universities were beginning to produce increasing numbers of scientists with advanced training, and, so the argument goes, physics and chemistry were finally to the point where science was useful in solving the problems of business enterprise. The classic example of the new model was the German chemical industry, and the first American instance was the General Electric Research Laboratory, which arose de novo in 1900. An implicit assumption of the early literature on industrial research was the need to explain how academic scientists moved into a basically hostile environment dedicated to the production of continuous commercial innovation, rather than the unfettered pursuit of pure science. It will come as no surprise that the historical situation was a little more complicated than that.

Important scholarship by Alfred Chandler, Louis Galambos, David A Hounshell, John K Smith, Reese Jenkins, Stuart W Leslie, Leonard Reich, and George Wise among others has sketched the outline of a different interpretation of the history of industrial research.[4] Chandler and Galambos have stressed the relationship of industrial research to corporate strategy and the goals of a new class of professional managers. In their hands, research was a resource to be allocated like other corporate resources, an asset to be applied when it would do more good than building a new plant or modernising an old one, expanding production, integrating forward or backward, or taking other steps to improve the bottom line. Jenkins and Reich have demonstrated in different ways how industrial research was used strategically to buttress market position and to maintain the status quo in an industry. And Wise and Leslie have both focused on the importance of the personal style of research directors and the emergence of a ‘culture’ of research in explaining the success of the industrial research model.

These new perspectives have given us a clearer historical account of the rise of corporate industrial research in America, but there is still a bias in the literature toward stressing the discontinuity between nineteenth-century business uses of technical expertise and the twentieth-century model epitomised by the ‘R&D pioneers’. But continuity with earlier modes of research organisation is a striking theme of each of these cases. Early industrial research laboratories were more closely tied to the needs of the business than one would suspect from reading the current history of the institution.

This point emerges strikingly from the Kodak case, where the principles laid down by Kenneth Mees before the First World War, based largely on his experience as joint managing director of the photographic firm Wratten & Wainwright, continued to govern Kodak research until well after the Second World War. Mees’s vision succeeded admirably when Kodak was still largely a photographic company dominant in its market. It also applied reasonably well in the 1920s and 1930s as Kodak moved aggressively into chemicals, fibres and plastics derived initially from its chemical requirements for photographic manufacture. But the post-war world brought new challenges to Kodak research in the form of strenuous competition (e.g., from Polaroid and Xerox) and legal opposition (as in the Berkey Photo case) in some of its basic markets, while new technologies of ‘electronic photography’ (video, optical discs, etc.) threatened its core businesses. To what degree did the original research vision of Mees and Eastman adapt to the challenges of diversification? This paper can’t answer that question fully, but I will be able to sketch the relevant historical background.

Evolution of research at Kodak, 1880–1920

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201311/004When Kenneth Mees was hired by George Eastman in January 1912, the Eastman Kodak Company already had a thirty-year tradition of technical innovation.[5] Eastman himself had handled much of the experimental and development work in the early years, from making gelatin dry plates in 1880 and photographic printing papers in 1884 to the introduction of the new system of roll film and Kodak camera in 1889. As early as 1886, Eastman had hired a locally-trained chemist, Henry Reichenbach, to work on photographic emulsions. Two years later, Reichenbach also began to investigate the applicability of the new plastic celluloid as a film base. By the early 1890s, Reichenbach had become manager of the Kodak Park works and Eastman hired analytical chemist S Carl Passavant to assist him. At the end of 1891, Reichenbach, Passavant and a colleague were fired when Eastman discovered they were planning to go into business in competition with Eastman Kodak.

But throughout the 1890s, Eastman turned increasingly to technically-trained chemists and engineers for assistance in product and process improvement. Harriet Gallup, an MIT chemist, and Darragh de Lancey and Frank Lovejoy, two MIT-trained engineers, joined Kodak in the mid-1890s. Lovejoy and Gallup both worked in the Experimental & Testing Laboratory at Kodak Park, an organisation set up in 1890 to do quality testing on raw materials (such as silver nitrate, gelatin and halide salts). By the turn of the century, Kodak Park chemists were also investigating processes for producing nitrocellulose and other basic chemicals used in producing film. Lovejoy and de Lancey both took on increasingly more manufacturing responsibility at Kodak Park, and in 1906 Eastman brought in David Reid, a pharmaceutical chemist, to head the Experimental & Testing Laboratory and work on new photographic papers and cellulose acetate non-flammable film. By 1910, Eastman had become increasingly anxious about colour photography and set up a colour laboratory to work on the problem. Colour represented a threat to Kodak’s dominant position in the photography business and, as Eastman later observed, he wanted to ‘control the alternatives’.[6] Within the next two years, Eastman was to take an even more decisive and long-range approach to the problem of ‘controlling the alternatives’ by establishing the Eastman Kodak Research Laboratories.

In the winter of 1911–1912, while visiting Europe in connection with Kodak’s new ventures in cine film, Eastman had dinner with Carl Duisberg of Bayer in Elberfeld. As Mees later recalled, Duisberg – whose laboratory was among the first in the German chemical industry – turned to Eastman and said, “We have 700 chemists in our organization. How many have you got?” Kodak had closer to seven than 700, and Eastman did not answer Duisberg directly. Shortly after this encounter, Eastman told Joseph Thacher Clarke, his technical intelligencer in London, that he refused to “be talked to in that way. I’m going to have a research laboratory, too!” Eastman asked Clarke to recommend someone to organise and direct the projected laboratory, and Clarke suggested Kenneth Mees.[7]

Kenneth Mees was a 29-year-old chemist who was already making a name for himself in photographic circles.[8] Trained at University College London with the leading physical chemist Sir William Ramsay, Mees had already published several dozen papers and monographs on photographic science and technology and a 1907 book on Investigations on the Theory of the Photographic Process (written with his close friend and collaborator, Samuel Sheppard).

Work at Wratten & Wainwright (where he was joint managing director and a 25 per cent owner) on panchromatic film and colour filters also made him an international expert on colour photography. Eastman had already met Mees on a 1909 visit to Kodak Park (Mees had been doing some consulting work for the American Bank Note Company and asked to visit Eastman while he was in New York), so he knew of his work at Wratten & Wainwright. Clarke arranged a meeting between the two men in late January 1912. When Mees mentioned to his partner Wratten that Eastman had asked to see him, Wratten told him, “he’s going to ask you to America”. Mees was sceptical and said Eastman was probably just being friendly, to which Wratten replied, “George Eastman doesn’t spend his time being friendly”. Mees had been due to go to Budapest on the day of their meeting, but upon learning this, Eastman called Mees and confirmed what Wratten had suspected – that he wanted Mees to move to Rochester. Wratten suggested to Mees that he wouldn’t object to selling Wratten & Wainwright if Mees was interested in Eastman’s offer. Mees cancelled his planned trip to Budapest, and by the time Eastman and Mees met the next day, Mees had his partners’ agreement to negotiate for the sale of the business and his wife’s agreement that moving to America would be “quite all right with her”.

Eastman got right to business during their conversation – his first question to Mees was “Will you come?”. Mees, reasonably enough, asked him what job he had in mind. Eastman replied, “build a research laboratory and take charge of it”. He explained that he had been impressed with Duisberg’s lab at Elberfeld and would like Mees to design, build and operate “something of that sort” at Kodak. Mees was intrigued by the prospect if Eastman was willing to equip and staff such a laboratory, but would agree only on the condition that Eastman buy Wratten & Wainwright. That was arranged the next day after a brief negotiation (Eastman paid Mees’s asking price of £22,000), and Eastman had found himself a research director.[9]

Why was Eastman interested in establishing a new research laboratory at this time? The examples of Bayer, other German chemical companies, and General Electric, Du Pont, AT&T and other leading companies closer to home were certainly one factor, but corporate fashion alone does not fully explain his motivation. The question of colour photography, and ‘controlling the alternatives’, is another important factor. His decision to pursue Mees, a leader in the field, as his research director certainly points in that direction; indeed, Mees later recalled that Eastman was ‘crazy about color’, and Eastman described Mees at the time as ‘peculiarly fitted for the position, both on account of his education and his practical experience, he being a chemist, a physicist, a practical manufacturer of color sensitive dry plates [and] one of the best known authorities in color photography’. Most important, however, was probably Eastman’s increasing concern over the rise in anti-trust sentiment at both the state and national levels. As early as 1903, Eastman Kodak had faced state action against its alleged monopoly position in the photographic supply industry, and by 1911 there were signs that Kodak might also fall under Justice Department scrutiny as Standard Oil and American Tobacco recently had.

These issues were very much on Eastman’s mind in 1911 and 1912, and were also being discussed in Rochester business circles. Indeed, when Mees visited the city in April 1912, Kodak general manager Frank Lovejoy brought him to dinner at the City Club, where he heard the visiting speaker Louis Brandeis discoursing on “the inequities of big corporations” and arguing that “they wouldn’t do any research because they were self-satisfied with their positions and didn’t need any technical advice”. Mees took issue with Brandeis, saying he “had just visited various big corporations, and they were all enthusiastic about research”. But they were enthusiastic for a different reason than Mees may have supposed – not for short-term gains in productivity, but rather for long-range returns on investment. Eastman, like his counterparts at other large corporations, saw research as the solution to new restraints created by anti-trust measures. If mergers and horizontal combinations would no longer be allowed, research and development could lead to continued growth through the discovery of new markets and new businesses in a manner consonant with the Progressive rejection of traditional ‘big business’ practices. Thus, investment in research appealed to Eastman for two reasons: it was both good business (‘controlling the alternatives’) and good public policy.[10]

In his initial talks with Mees, Eastman stressed his interest in the basic science underlying photographic practice and his vision that the new laboratory would be responsible for the ‘future of photography’. These assurances aligned well with Mees’s interest in continuing his research into the nature of the photographic process and he began to plan the kind of laboratory he would like to run. Eastman agreed to allow free publication of results, one of the first issues Mees raised with him. Later he obtained agreement to freedom from the day-to-day business of the Kodak Park Works and an arrangement whereby Mees reported directly to Eastman and obtained budget approval from him. By early April, Mees was in Rochester to sign a contract, design the laboratory building, and make further plans for operating the new labs. On this trip he also visited Willis Whitney at the General Electric Research Laboratory in Schenectady, New York. As he later recalled, ‘I knew nothing about running a research laboratory, of course; nobody did’, but he found Whitney’s model instructive. He was impressed with the semiworks manufacturing carried out in the laboratory, probably because Eastman expected him to continue producing Wratten & Wainwright’s panchromatic plates and colour filters in the new laboratory at Rochester. He also observed Whitney’s system for reporting results and keeping up with the research front. In this respect, he preferred the organisation of the Nobel Explosives Company’s laboratory, with which he was familiar from consulting work he had done for its director, William Rintoul, in 1911. Mees hoped to establish an organisation neither as formal as Rintoul’s nor as informal as Whitney’s, but well-adapted to the particular needs of Eastman Kodak’s position in the photographic field.[11]

Mees returned to Rochester in August 1912 to take up his new duties full-time, and by the spring of 1913 the laboratory was fully staffed and in operation. Two departments were devoted to manufacturing Wratten & Wainwright plates and colour filters, while other well-equipped laboratories were devoted to physical chemistry, spectroscopy, sensitometry and practical photography. Mees brought a number of researchers with him from England, including: J G Capstaff, who had made filters for Wratten & Wainwright and later worked on motion picture and colour photography; J I Crabtree, who did research in photographic chemistry; and his old friend Sheppard in physical chemistry. (The Anglo-American atmosphere of the laboratory remained strong. In the early 1920s, one of the first films made with Capstaff’s new process for amateur movie film was entitled Out of the Fog; it showed Mees landing on the shores of nearby Lake Ontario with a contingent of Britons to found the Kodak Laboratories.) Other early workers included a trio of scientists from the National Bureau of Standards (P G Nutting and L A Jones in optics, and A S McDaniel in inorganic chemistry) and, in 1914, Joseph Thacher Clarke’s son Hans in organic chemistry. This strong early group of researchers began a sustained programme of investigation into sensitometry, the physical chemistry of development and the photographic image, and the role of gelatin and other materials in the photographic process. Mees’s laboratory was both an institute for the study of the science of photography and an organisation dedicated to solving the technical problems of Kodak’s day-to-day business. As Mees later recalled, right from the start there was ‘lots of sales service work, [and] lots of pure science’. This dual role – a commitment to fundamental research coupled with a strong tradition of practical innovation – characterised the entire Mees era of Kodak research.[12]

Mees became something of a philosopher of industrial research over the years (‘one of the early apostles of the doctrine’, as his son later characterised him). His writings on research management stressed both the importance of business sense and the need to focus the work of a laboratory for it to be successful. This is evident from his first paper on the subject, an article submitted to Science in February 1916 – this and several later articles were combined into Mees’s widely-read monograph on The Organization of Industrial Scientific Research (1920).[13] After an initial discussion of the variety of industrial laboratories (works labs, those devoted to process and product improvement, and those devoted to the fundamental science associated with an industry), Mees articulated several themes that had governed his direction of Kodak research.

First was an emphasis on cooperation and teamwork. Mees believed that it was ‘necessary…to dismiss from the mind completely the idea that any appreciable number of research laboratories can be staffed by geniuses. If a genius can be obtained for a given industrial research, that is, of course, an overwhelming advantage which may outweigh any disadvantages, but we have no right to assume that we can obtain geniuses; all we have a right to assume is that we can obtain, at a fair rate of recompense, well trained, average men having a taste for research and a certain ability for investigation. The problem, then, is how can we obtain the greatest yield from a given number of men in a given time?’[14] The answer, Mees reiterated, was interdisciplinary cooperation aimed at the common objective of solving research problems specific to the industry in which the laboratory was situated. The individual’s role was cast within the overall framework of the laboratory’s mission.

Interestingly enough, Mees’s attitude toward teamwork and obtaining ‘…the greatest yield from a given number of men…’ seems to have led to a continuing low profile for Kodak researchers. Despite the Laboratories productive contributions in many areas of science, few Kodak scientists attained the stature of GE’s Irving Langmuir or Du Pont’s Wallace Carothers. Several Kodak scientists have certainly been widely known: in addition to Mees, of course, one can point to Hans Clarke’s reputation for organic synthesis in the 1920s; C J Malm’s work on cellulose derivatives; Maurice Huggins’s theoretical investigations of the thermodynamics of polymer solutions; and Arnold Weissberger’s contributions to the organic chemistry of colour photography (in addition to his well-known editorial work on organic chemical techniques and synthesis). While Kodak has had its research stars, their magnitude was not as bright as some of their counterparts at General Electric, Du Pont or Bell Labs.[15]

While Mees and his associates believed in teamwork, they were also wary of the stultifying effects of over-organisation. Commenting in 1935 on the tendency to try to plan research formally, Mees observed ‘I don’t feel that that is any use at all – God is not an efficiency engineer’. He continued with a statement on who should direct research work that became a standard text for Kodak scientists and engineers: ‘…the best person to decide what research work shall be done is the man who is doing the research, and the next best person is the head of the department, who knows all about the subject and the work; and after that you leave the field of the best people and start on increasingly worse groups, the first of these being the research director, who is probably wrong more than half the time; and then a committee, which is wrong most of the time; and, finally, a committee of vice presidents of the company, which is wrong all the time.’[16]

Research was a gamble, Mees often asserted; the most important decision was not in controlling costs, but rather in deciding which projects should be pursued and which should be dropped. To do this well, a research director needed both scientific acumen and practical experience, a theme sounded often in Mees’s writings. In a letter to a former colleague written in 1956 (on the fiftieth anniversary of his entering the photographic industry), Mees said ‘I think that the training at Wratten & Wainwright was very good for me. I had to run the whole business, with the exception of the engineering and actual factory management…and I had to make the company pay. I didn’t know anything about business or accounting or salesmanship, so I had to learn, and the training that I got has been useful to me ever since.’ Under Mees’s direction, the Kodak Research Laboratories had close ties to the manufacturing and sales side of the business from the beginning, as noted earlier, and Mees always kept a close watch on new commercial trends in assessing what his staff should do next.[17]

The final element of Mees’s approach to research management was an emphasis on the communication of results, both within the laboratory and with the scientific community at large. As noted earlier, one of the first aspects of the new laboratory with which Mees concerned himself in 1912 was the question of internal reporting and the importance of external publication of results. An elaborate abstracting system was set up to help workers keep track of the scattered photographic literature, and Mees encouraged publication of results in the open literature as a means of gaining visibility for Kodak and encouraging others to work on problems of interest to the company. To further this goal, a series of Abridged Scientific Publications was initiated in 1913; by the time Mees retired in 1955, more than two thousand contributions had been published by Kodak researchers.

An important organisational device instituted at the outset was the conference system. The laboratory was organised into departments roughly on disciplinary lines (physics, inorganic chemistry, organic chemistry, etc.), but the series of conferences was organised around such specific problem areas as general or colour photography. Each group included researchers working in the area and representatives of other staff and production departments concerned. The morning conferences (held weekly in each problem area) provided an efficient mechanism for Mees and his associates to keep track of the current work of the laboratories while encouraging a cooperative approach to mission-oriented problems.[18]

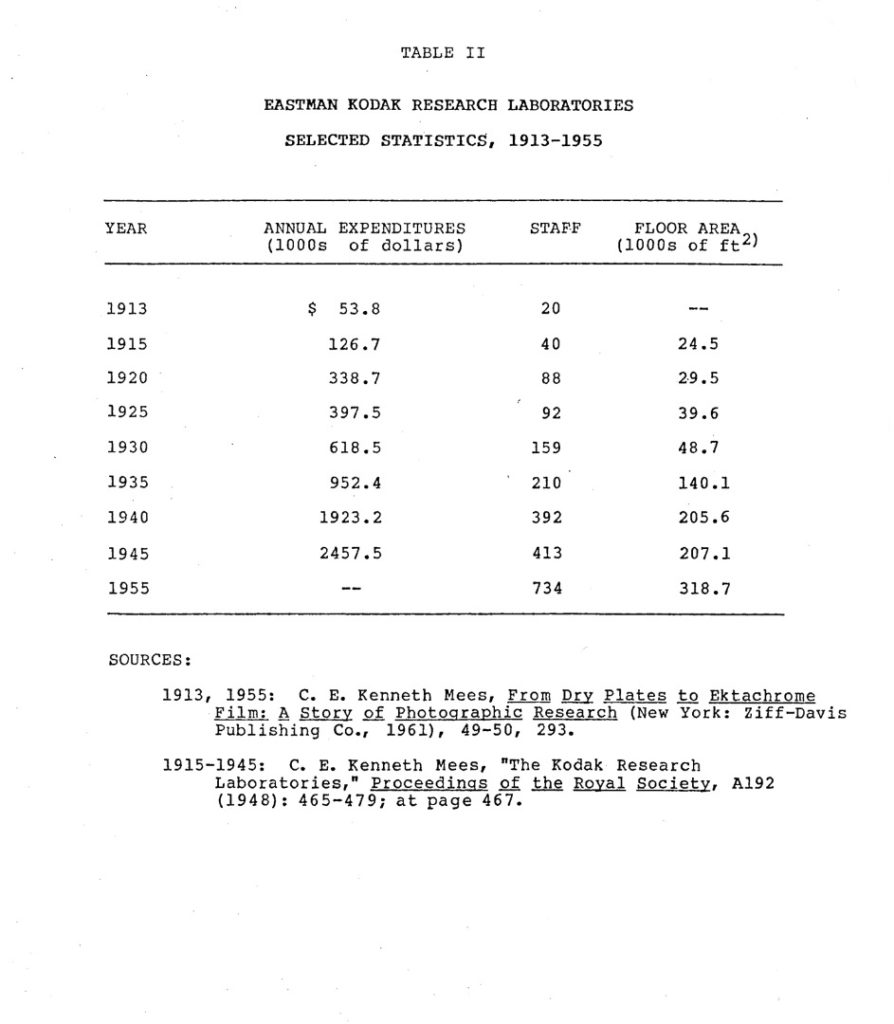

The conference system became an institution at the Kodak Research Laboratories, and a hierarchy developed. As the laboratories grew (from fewer than one hundred workers before the First World War to nearly a thousand by the late 1950s, see Table II), controlling the flow of information became a more complicated matter. In addition to the formal scientific conferences, there were weekly meetings of laboratory department heads, weekly division meetings (often involving as many as 150–200 people), and periodic conferences – of the research directors with senior research associates and laboratory heads. Even with the evolution of a hierarchy of administrative meetings, the traditional problem conferences – involving research supervisors, bench scientists and front-line production people – remained at the centre of the system.[19]

The policies enunciated by Kenneth Mees before the First World War – such as a firm belief in cooperation and teamwork, a wary attitude toward the detrimental effects of over-organisation, an emphasis on the importance of keeping the needs of the business firmly in mind, and a strong commitment to communicating results within the firm and to the scientific community – governed Kodak research throughout the Mees era (until his retirement in 1955) and left an outstanding legacy of achievement in photographic science and technology.

The challenges of diversification, 1920–1950

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201311/005The principles of research management practice at Kodak were not strikingly different from those governing research at other industrial laboratories during this period, yet Kodak was notably more successful than most. The reasons lie, I think, in what Mees called the ‘convergent’ nature of their research and development work. During the first few decades of its existence, the Kodak Research Laboratories focused on exhaustive study of every aspect of the photographic process, while developing new products related to Eastman’s initial vision of going after the amateur mass market. During this time, Eastman Kodak was the undisputed leader of a vast market. In this respect, Kodak’s position in photographic research was very similar to that of Bell Labs in telecommunications. During the inter-war years, while Kodak continued to dominate in photography and planned its strategy in that context, Mees’s vision of industrial research was well-adapted to its niche. And the first research forays outside of photography per se were linked to Kodak’s need for raw materials for photographic chemicals, new kinds of film and sensitising dyes, and the like.

The first chemical ventures of Eastman Kodak are good examples of this point. Wartime demand for cellulose acetate (for airplane ‘dope’) had led Kodak further into the wood distillation chemicals field, and their post-war needs for larger supplies of acetic acid and acetone to make cellulose acetate films led to a 1920 decision to acquire a wood distillation plant in Kingsport, Tennessee. By the mid-1920s, experiments on acetate fibre were begun in the Rochester laboratories with an eye to finding a mass market for Tennessee Eastman’s output that would bring down the price, thus benefiting the photographic division of the company. New fibres developed by Kodak researchers were marketed in 1931, and related cellulose acetate plastics in 1932. Kodak was well on its way to becoming a major chemical manufacturer as a result of its interest in finding a cheap and sturdy source of supply for raw materials used in its core photographic business.[20]

The First World War was also the proximate cause of Eastman Kodak’s entry into the commercial production of synthetic organic chemicals. American industry was utterly dependent upon German manufacturers for fine chemicals on the eve of the First World War, including a variety of sensitising dyes and developing agents for photography. Wartime embargoes created severe shortages. It was their interest in ensuring a supply of these important organic chemicals that prompted Kenneth Mees and Hans Clarke to establish a manufacturing unit in September 1918 to produce and sell a variety of organic reagents needed by industrial and academic organic chemists throughout the United States. Commercial interests and patriotic motivations meshed nicely, and the new Eastman Organic Chemicals operation of the Kodak Research Laboratories prospered. From an initial list of some 150 products, the Eastman Organic Chemicals operation expanded steadily to selling some 3,500 high-margin specialty chemicals by the mid-1950s.[21]

Both the Tennessee Eastman and Eastman Organic Chemicals developments were related to opportunities arising from conditions during the First World War and the technical needs of the photographic side of Kodak’s business. A third example of diversification emerging from the fruitful interaction of market opportunity, Kodak research, and the technical needs of existing businesses can be found in the case of Distillation Products. In 1929, Kenneth Hickman, another English-trained chemist who had joined Kodak in 1925, was investigating the use of high vacuum distillation with an eye to improving film-drying techniques. His work soon led to a new technique of molecular distillation. By using improved vacuum pumps and high-boiling organic liquids, Hickman was able to concentrate the vitamins present in fish oils on a commercially viable scale. Within a few years, Kodak established Distillation Products, Inc., and went into the vitamin business. Again, as in the case of Tennessee Eastman’s entry into plastics and fibres and the decision to manufacture synthetic organic chemicals, Hickman’s project began with a goal related to the improvement of photographic manufactures.[22]

The congruence of technology, markets and R&D evident in these three examples of Kodak diversification between the wars also continued to work in more traditional areas of Kodak research. Mees and his lieutenants had kept a careful eye on trends in photography after the First World War, and they devoted considerable effort to new ventures in industrial and commercial photography (including documentary uses), X-ray photography and amateur motion picture photography, in addition to continuing extensive research on colour photography. Mees likened the Research Laboratories to the intelligence department of an army, keeping management informed of new market opportunities and developing new products to meet untapped demand.[23]

Kodak in the post-war world

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201311/006The fit between Kodak’s overall business strategy and the contributions of the Research Laboratories was a key factor in the company’s continued prosperity through the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s. And Kodak continued to use the same strategy after the Second World War. In 1952, the company established the Texas Eastman Company to produce ethyl alcohol and butyric acid (key raw materials for operations at Rochester and Kingsport). Two years later, Kodak decided to take the further step of making polyethylene at Texas Eastman; they were already manipulating ethylene, and polyethylene was an exciting new plastic with good prospects. But Texas Eastman was competing in polyethylene with most of the major chemical producers (including Allied, Dow, Du Pont, Monsanto and Union Carbide) in a new market already threatened with overcapacity. A similar situation faced Tennessee Eastman’s move into polyester fibres in the mid-1950s. In these and other areas outside of photography during the 1950s and 1960s, Kodak faced stiff competition, a situation very different from their traditional position in the photographic industry. At the same time, Kodak’s centre of gravity was shifting toward chemicals and other non-photographic products; by the late 1950s, nearly one-third of the Kodak sales dollar came from chemical products.[24]

As contemporary analysts observed, Kodak had evolved a conservative management culture that perceived Kodak’s priorities from the viewpoint of the ‘image formation’ industry, yet their problems involved a broader array of markets requiring different responses.[25] Kodak continued to perform strongly in areas of traditional strength, but responded sluggishly to new opportunities. A thorough exploration of Kodak innovation in the post-war period is a subject for another paper, but let me note a few salient examples. Perhaps the most successful of all Kodak product introductions since 1960 was the Instamatic camera, first marketed in 1963. This camera, using a cartridge-loaded film, was conceived in the grand tradition of Eastman’s original vision of making cameras as easy to use as a pencil. Kodak found a new amateur market in Instamatic users, and subsequent price reductions and pocket models brought the camera within range of the broadest possible mass market.

However, against the success of the Instamatic, look at several other episodes in the post-war period. Eastman Kodak had a strong hold on the office copier market during the 1950s with its Verifax (wet) system, but Xerox’s new electrostatic process had virtually taken over by the mid-1960s. When Kodak did introduce a technologically sophisticated high-speed copier (the Ektaprint) in 1975 after an inordinately long 12-year period of development, Xerox moved quickly with an improved model and Kodak lost the initiative. Kodak turned down an opportunity to acquire Edwin Land’s new Polaroid process after the Second World War, apparently because they banked on high-volume, low-cost photography, not the high-cost, relatively low-volume approach represented by the Polaroid. But Land’s obsession with instant photography was shared by a large and growing segment of the amateur photography market, and Kodak’s formerly unassailable position began to erode. Kodak did not respond with its own instant camera until 1976, and never captured a large share of the instant photography market. (The competition with Polaroid did not end well, leading to a landmark patent infringement case over the technology of instant photography, which Kodak lost in 1991, paying a settlement to Polaroid of $952 million.) Finally, the introduction of Ektachem clinical analysers (1981) and the Kodak disc camera (1983) did not live up to expectations; both were technological marvels, but not what the marketplace wanted.

How had Kodak’s research organisation fared during this period? The guiding principles of the Mees years still prevailed. Mees’s successor, C J Staud, was a product of the traditional Research Laboratories atmosphere and Mees’s protege in emulsion research. Staud inaugurated one of the longest-standing of the conferences, the Couplers Conference, around 1940; it eventually spawned other conferences on colour research, and Staud’s role as ‘czar’ of the Couplers Conference was an element in his promotion to director of the Laboratories when Mees became vice-president in 1947. Staud’s successors (John Leermakers and W T Hanson, who ran Kodak research through the mid-1970s) had both joined the Laboratories in the mid-1930s, the heyday of the Mees era, and both were veterans of emulsion and colour photography research, traditional strong suits of Kodak’s research organisation.[26]

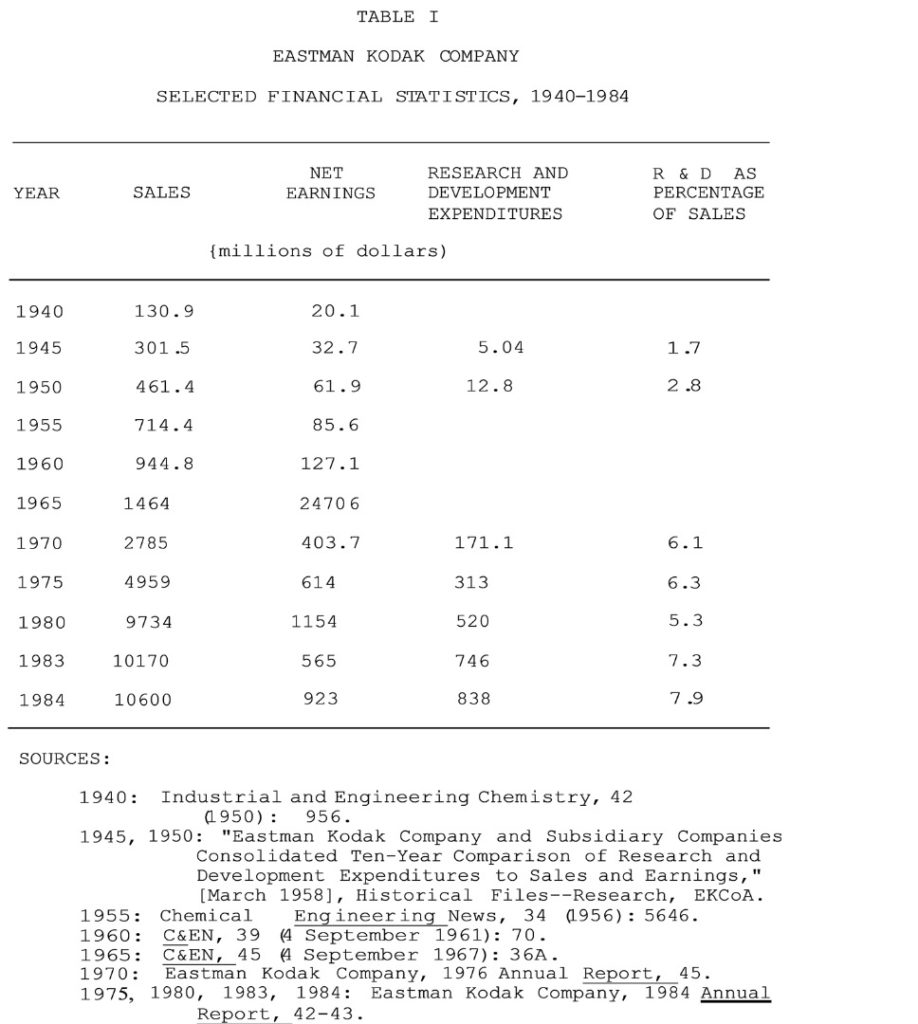

As these hints suggest, the conservative mind-set of top management may well have been present in Kodak’s research managers as well. The Laboratories continued to produce first-class results in colour photography and organic chemistry, but Kodak’s competitive position called for a different, more flexible approach by the 1970s. The research organisation at Kodak had become, if anything, less flexible, an inevitable result of its growth in size and scale over the years (see Tables I and II). Layers of research administration grew inexorably, a fact that captured Kenneth Mees’s attention; in 1959, he wrote to Roy Davies that he ‘recognize[d] the continual drive toward planning and toward development rather than research, but remain a convinced heretic’. Nevertheless, the second edition of his book on The Organization of Industrial Scientific Research (1950), twice the length of the 1920 edition, devotes nearly three times as much space to issues of planning and administration of research.[27]

There were signs by the 1980s that Eastman Kodak was taking measures to restore the close fit of technology, markets and R&D that characterised the inter-war years. In November 1984 the company undertook a major reorganisation designed to ‘make employees more aware of competitive pressures’. As part of the change, the company decentralised around business units geared toward specific markets in commercial and information systems, photographic products and diversified technologies (such as clinical systems, computer memory products, and specialty research chemicals). Kodak also established an internal organisation devoted to finding and supporting new ideas, including Offices of Innovation and a Ventures Board. Finally, the company committed itself to a break with tradition concerning research and development. While Kodak had historically generated its own technology, new strategies contemplated or already in practice included joint ventures (such as that with Matsushita and TDK in video); acquisition of high-technology companies (as with Atek in text-editing systems); and increasing use of outside research agreements with university laboratories and consortia (such as the Microelectronics and Computer Technology Corporation). There was also a short-lived detour into pharmaceuticals with the 1988 purchase of Sterling Drug for $5.1 billion, but Kodak learned the hard way that their expertise in chemicals did not translate readily to the world of healthcare. Sterling was sold at a loss in 1994.[28]

Kodak was particularly concerned about new developments in ‘electronic photography’ (namely video and optical disc technology), as well as challenges in linking advances in computer technology to its traditional focus on image technology. These innovations, just taking shape in the early 1980s, sparked a transformation in imaging, leading to the demise of silver halide photography and its replacement by digital photography. In a classic case of what Clayton Christensen has termed the ‘innovator’s dilemma’, Kodak failed to adapt rapidly enough to the new market realities, continuing to bet on its dominance in an increasingly outmoded technology, convinced that the new digital technology could not perform as well as their business model – of silver halide film and prints, sold through an ecosystem of photofinishing partners – in meeting customer preferences.[29] But the quality of digital photography improved rapidly; as its costs declined, it put new digital cameras within reach of a mass market.

Kodak was not oblivious to these developments. An internal study in 1981 predicted that digital photography would truly arrive in the 1990s, but Kodak was still committed to trying to use digital tools to improve their silver halide products and services, not appreciating how rapidly the ground would shift under their feet as the Internet and ubiquitous cell phone cameras completed a move away from paper prints to digital images. Kodak turned its attention toward building a position in digital cameras, but its financial position weakened through the 1990s as the market share for silver halide photography declined, which made it more difficult to make the necessary changes to respond effectively to shifting customer demands. Ironically, Steven Sasson of the Kodak Research Laboratories had actually been the first to create a digital camera in 1975; but when he pointed out that he’d developed a ‘filmless photography’, his manager said, “That’s cute – just don’t tell anyone about it”. Just as Xerox had not capitalised on the elements of the personal computer invented in their California laboratories, Kodak did not move quickly enough to catch nimbler competitors in response to the new wave of digital technologies. These conditions proved to be a bridge too far for Kodak’s business model, and the company declared bankruptcy in 2012, eventually emerging from the reorganisation a smaller and very different enterprise.[30]

In a sense, though, this brings us full circle to the orientation that characterised George Eastman’s initial vision for the business. The institution that he and Kenneth Mees created to insure the ‘future of photography’, the Kodak Research Laboratories, had found productive ways to merge technology, markets and R&D in pioneering fashion. Mees later recalled that ‘Mr. Eastman did not care about science in general, or even the science of photography, as such. What he wanted from the laboratory was new products and profit.’[31] Kenneth Mees and his colleagues built that laboratory into a successful organisation that found those new products and profits over the next seven decades, just as Eastman had envisioned. One might ask if Mees’s background as a chemist and the first wave of diversification into new enterprises like Eastman Organic Chemicals, Tennessee Eastman, Distillation Products, and Texas Eastman created a certain path dependency in the evolution of Kodak research. By the 1960s and 1970s, however, Kodak’s research enterprise had certainly become as diversified as the company itself. Chemists remained an important professional discipline, but there were also physicists, engineers and technologists in many other fields. What hadn’t changed, however, was a culture and business model still centred on the technological system of silver halide photography. The generation of leaders trained by Mees and his management colleagues built an enviable legacy – until Kodak’s ability to change rapidly enough to keep up with the new challenges of diversification flagged in the dawning digital age.

Tags

Footnotes

At the time I did research on this paper (1985), these records were administered by the Business Information Center at Kodak headquarters in Rochester, New York. I thank M Lois Gauch and her staff for their assistance in using these materials. Walter Cooper and Roger Cole, then with the Kodak Research Laboratories, were also instrumental in facilitating my research in Rochester. Since I conducted my research, these materials were donated by Kodak to the University of Rochester Libraries in 2004 and 2006, where they can now be consulted as the Kodak Historical Collection #003, D.319, Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation, River Campus Libraries. For the finding aid, see https://rbscp.lib.rochester.edu/finding-aids/D319#processinfo

Two relevant books that appeared after I completed the original version of this paper in 1985 are Eastman Kodak Research Laboratories, Journey: 75 Years of Kodak Research (Rochester, NY: Eastman Kodak Company, 1990), and Douglas Collins, The Story of Kodak (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1990). See also Nicolas Le Guern’s doctoral dissertation, Contribution of the European Kodak Research Laboratories to Innovation Strategy at Eastman Kodak (Leicester: De Montfort University, 2017). Back to text

Since the 1980s, there has been considerable additional scholarship on the history of industrial research and applied science. An extended historiographic review is beyond the scope of this essay, but two of the most interesting books that draw on this literature are Sally H Clarke, Naomi R Lamoreaux and Steven W Usselman (eds), The Challenge of Remaining Innovative: Insights from Twentieth-Century American Business (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2009); and Steven Shapin, The Scientific Life: A Moral History of a Late Modern Vocation (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008).

Robert F Bud has made significant contributions to scholarly work in this area. One of his earliest publications looks at the influence of industrial research models on cancer research: ‘Strategy in American cancer research after World War II: a case study’, Social Studies of Science, 8 (1978): 425–459. See also his books on The Uses of Life: A History of Biotechnology (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993); Penicillin: Triumph and Tragedy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009); and his recent articles, including ‘“Applied science”: a phrase in search of a meaning’, Isis 103 (2012): 537–545; ‘Framed in the public sphere: tools for the conceptual history of “applied science” – a review paper’, History of Science, 51 (2013): 413–433; and ‘Modernity and the ambivalent significance of applied science: motors, wireless, telephones and poison gas’, in Robert F Bud, et al (eds), Being modern: the cultural impact of science in the early 20th century (London: UCL Press, 2018): 95–129. Back to text

Elizabeth Brayer reports that Kodak ‘could have fathered xerography as well as photography. But through Dr C E Kenneth Mees, who was essentially a chemical man, Kodak consistently turned down Chester Carlson’s dry photographic process, basically a physics operation’; Brayer, George Eastman (note 10), 607.

On the competition with Polaroid, see Mark Olshaker, The Instant Image Edwin Land and the Polaroid Experience (New York: Stein and Day, 1978), esp. 220–234; and Ronald K Fierstein, A Triumph of Genius: Edwin Land, Polaroid and the Kodak Patent War (Chicago: Ankerwycke Publishing, 2015). Back to text