A royal gift? Mrs Strangways Horner’s small silver clock, 1740

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191110

Abstract

This article celebrates the rediscovery of a small silver-cased clock allegedly given to Mrs Strangways Horner by Lady Archibald Hamilton on behalf of Augusta, Princess of Wales in 1740. As well as being a very early example of high rococo styling in such a piece, it represents the interest that scientific instruments and timepieces held for Prince Frederick and Princess Augusta, recently recognised by the acquisition for the V&A of the mantel clock purchased by Prince Frederick in 1736. Research in the Royal Archives has confirmed their joint patronage of established Huguenot jewellers in London and Bath, who supported these royal patrons by providing extended credit, although the exact relationship between Princess Augusta, Lady Archibald Hamilton and Mrs Strangways Horner, and the reason for the gift of this clock, is unrecorded. The original choice of a re-purposed watch movement and dial in such a fine piece is also discussed and explained.

Keywords

Antiquarian Horology, Augusta, Bath Infirmary, bonds, Clock, Court, Daniel Garnier, Frederick, Henley; Paul de Lamerie, Henry Perry, Huguenot, Isaac Lacam, Jewellers, Lady Archibald Hamilton, Mrs Strangways Horner, Park Place, patronage, Peter Dutens, Prince of Wales, Princess of Wales, Rococo, Royal Archives, Silver, Soho craftsmen, toilet service, trade cards, Victoria and Albert Museum

Description of the clock

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191110/002

Inscribed on the domed back of the silver case is: ‘Given by the Right Honble. the Lady Archibald Hamilton, Lady of the Bedchamber, Mistress of the Robes and Privy Purse to her Royal Highness the Princess of Wales, Sepr. 1740 TO Mrs STRANGWAY HORNER’

The exceptionally fine chased, repoussé silver body principally consists of a classical figure, seated in a large stylised scrolling shell supposedly in the form of a boat, fronted by a curved balustrade. The figure holds a staff and the left arm supports an asymmetrical floral spray rising up behind and forming a frame for the circular drum containing the clock and dial. The figure is here identified as Minerva, combining male and female attributes, floral-patterned dress, and a soldier’s helmet.

While the front of the piece presents exceptionally fine craftsmanship, the rear view is less harmonious (see Figure 3), the repoussé silverwork having no backing as might be expected, and the reverse of the main body being supported with a somewhat inelegant triple strut of silver straps, soldered behind the figure to stiffen the whole assembly. The back of the clock movement is protected with the jointed, domed silver cover bearing the engraved citation, but there was originally a second, inner cover, now missing, but for which the steel retaining clips (now heavily corroded) survive inside the case. There are no hallmarks or signatures to be seen on the silver, so the identity of the silversmith, discussed later in this article, remains conjectural.

The piece was evidently always intended to be a clock, and must have always been a standalone piece. The bezel, with a convex glass protecting the dial, was fixed shut with three radial screws and the hand-setting and winding every day were effected by picking up the clock and turning round, so it has always been portable, in this form.

Although we believe that the silver body was created to be what we see today, the ebonised wooden base upon which the silver body sits is aesthetically and practically rather small for it. The shell scrolling extending beyond the base feels odd, but perhaps is part of the original design and was intended to emphasise the extravagant rococo nature of the whole. The base is attached to the silver body with two threaded silver bolts (see Figure 4) which pass through the base and are secured with four-lobed nuts underneath, entirely as one might expect for the period.

The movement

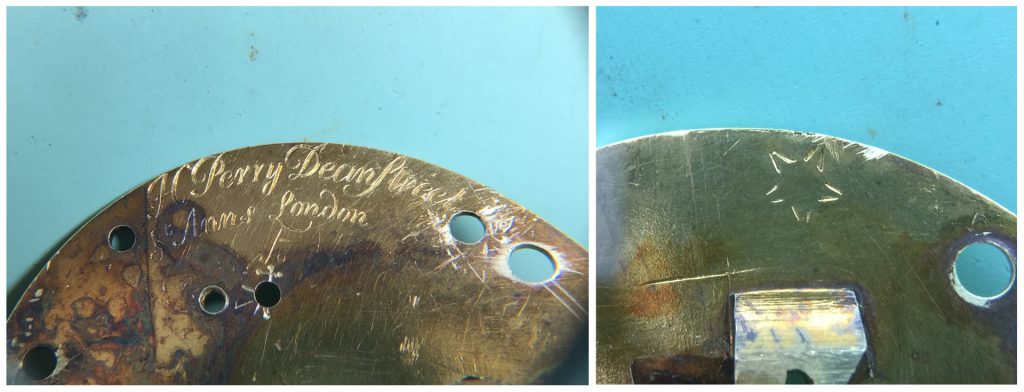

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191110/003The movement of the clock (see Figure 5) is a repurposed, high quality pocket watch movement c. 1700 by Henry Perry whose name is signed on the potence plate as of: ‘Dean Street, St Anns London’. The movement, which is a high-quality but fairly standard gilt-brass pocket watch movement of the day, has four Egyptian pillars, fusee and chain driving the usual five-wheel train, including the balance wheel (escape wheel), and a verge escapement with large steel balance. There is a typical, Tompion-style regulating disc on the slide plate which, with the balance cock, is finely engraved in the usual manner. The movement’s earlier life in a pocket watch is evidenced by the holes in the pillar plate for fixing of the earlier watch dial and for the case joint and the case bolt at the twelve and six o’clock positions respectively (see Figure 6). Perry, who was made a Freeman of the Clockmakers’ Company in 1691, appears to have retired from London to Bath in about 1720, twenty years before this clock was created, so it is doubtful he had any part in the clock’s creation (Baillie, 1929).

When the clock was made, in 1740, the movement was very nicely adapted for its use as a single (hour) handed clock. The case and dial of the watch were taken away and a new dial fitted, employing a large citrine (a lightly yellow-coloured quartz)[1] with a ‘beetle’ type pointer, in the centre forming the hand (see Figure 7). The central citrine quartz may be intended to represent the Sun. The citrine’s setting is commensurate with the date 1740 and has not subsequently been altered. The hand points to a nice quality, French-type blue and white enamel dial chapter ring, identical to those used on contemporary French oignon watches with alarm. It may in fact be such a dial, though if it had been previously used on an oignon watch one would have expected a small slot at VI to allow for the movement bolt, so this dial probably originated from France as a watch-dial but before use in a watch. On the dial side of the movement the original motion work was discarded and new high quality wheelwork was fitted with a new hollow steel post, fixed to the pillar plate to support the jewelled hand, a dovetailed brass slide fitted to retain it in place. As the dial was to be sealed up behind a silver bezel and glass, a hand setting mechanism was fitted, allowing the time to be set by a key on a square on the back of the movement.

Recycled parts

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191110/004The conclusion from this close inspection is that the clock appears to have been constructed from high quality but pre-existing parts specifically to create a suitable royal gift. The question might be asked ‘For a prestigious gift such as this, why was a movement and an enamel dial not made specifically to fit the silver case of the clock?’. The answer is almost certainly because the silverwork was the principal focus in this design and, very much in the French tradition, where the clock movement often took second place to the work of the case-maker, it would have been the silversmith who decided on the form of the case containing the clock. Unfortunately, in spite of the many horological products available in London at the time (then the most prestigious watch and clock-making centre in the world), there was no precedent for a clock movement of this precise shape and size, and it would simply have cost too much to produce a one-off movement. Equally, in 1740, the production of enamel dials, although considered the very latest fashion in watch design, was in its infancy in London.

Thus, a high quality watch movement from earlier in the century, which, with average use, would still have had many years life left in it, would have been a very sensible route. Many such recycled high-quality watch movements are found today in both later watch cases and fitted into small clock cases, some no doubt taken from gold cases, the re-casing paid for, plus a little extra cash released, by selling the gold. Similarly, with high-style enamel watch dials already available in France, there would have been no need to commission an expensive one in London. The use of a single hour hand may seem anachronistic in 1740, but single-handed clocks and turret clocks were by no means old-fashioned at that date, especially on such a decorative piece where the silver case and jewelled dial were the principal focus. It would have been considerably easier for the watchmaker to leave the movement with a two-handed dial, and clearly the use of the single large citrine hour hand was very much part of the intended design.

The gift

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191110/005According to the inscription, the clock was a gift to Mrs Susannah Strangways Horner from Augusta, Princess of Wales, via her leading courtier Lady Jane Hamilton.

The inscription with the month and year of the gift was likely dictated by the recipient or family member rather than the donor or donor’s representative.[2] It has not been possible to establish the relationship between Princess Augusta, Lady Archibald Hamilton and Mrs Strangways Horner. The Royal Archives demonstrate the extent to which officers of the household undertook such duties for their royal master and mistress. Princess Augusta, like her husband, Frederick, Prince of Wales, patronised French retailing jewellers and clockmakers established in London and in Bath; and as Princess Augusta’s Mistress of the Robes, Lady of the Bedchamber and Mistress of the Privy Purse, Lady Jane Hamilton would have made purchases from such retailers on behalf of her royal mistress. It is possible that Princess Augusta met Mrs Strangways Horner in Bath, when the royal couple visited that city in 1738; Bath was close to the Strangways Horner estates in the West Country, but the exact circumstances of their meeting and friendship has yet to be established.

Lady Archibald Hamilton was born Jane, daughter of James, 6th Earl of Abercorn (1661–1734); her husband Archibald was the younger brother of George Hamilton, 1st Earl of Orkney (1666–1737). The Archibald Hamiltons lived in the parish of St Martin in the Fields, close to the Royal Court at St James’s Palace and they met Frederick, Prince of Wales in 1729, shortly after that heir to the British throne arrived in London from Hanover (Vivian and White, 2006). The Court gossip, Lord Hervey, suggested in his correspondence that Jane Hamilton became Frederick’s mistress, but she was ten years Frederick’s senior and their close friendship is likely to have been platonic (Ibid). Frederick married Augusta of Saxe Gotha in April 1736, and the following year Lady Jane Hamilton was appointed Mistress of the Robes to the new Princess of Wales, and served as head of the female side of the establishment. Her fellow lady of the Bedchamber was Anne, Viscountess Irwin; Jane’s husband Lord Archibald Hamilton was Cofferer and Surveyor General to that same royal household (Ibid, p. 234; Walters, 1972).

The Hamiltons sold Park Place, near Henley to Prince Frederick and continued to spend time with that royal family; the artist John Wootton painted Lady Jane walking in the grounds of Park Place with Frederick, Augusta and their children (Vivian and White, 2006). In the group portrait of 1739 by J-B van Loo showing Augusta with members of her family and household, Lady Jane Hamilton supports the infant Prince Edward on her knee; whilst his elder brother Prince George, the future George III, is seated at the adjacent table (Royal Collection).

Mrs Strangways Horner, the daughter of Susannah Strangways, married Thomas Horner of Mells, Somerset in 1712. As she inherited the Strangways estates at Milton Clevedon, Dorset when her brother and sisters died without issue, she added the name Strangways to her married name (Hare, 1990). By 1735, her London house was in Grosvenor Street, Mayfair (The Country Journal, 1735). In 1736 she caused a scandal by arranging for their only daughter Elizabeth, aged 13, to marry Stephen Fox of Redlynch who was almost twenty years her senior.[3] A clandestine ceremony took place in March 1736 at Stephen Fox’s house in Burlington Street without the prior knowledge of the bride’s father who was outraged at the discovery (The Gentlemen’s Magazine, 1736). Stephen Fox was closely linked with the courtier Lord Hervey from 1726; they travelled to Italy and remained lovers so the marriage with the young Elizabeth Horner was a front to Stephen’s true sexual identity (Ilchester, Earl of.,1950). The story of Elizabeth’s marriage was later retold by Thomas Hardy in the short story ‘The First Countess of Wessex’, collected in A Group of Noble Dames, 1891.[4]

Mrs Susannah Strangways Horner was wealthy, attracting a substantial legacy from a cousin in 1737 (London Evening Post, 1737), in April 1738 she subscribed £50 to the new infirmary at Bath (The Daily Gazeteer, 1738; Brett, 2014).[5] In 1740 she gave her daughter Elizabeth a substantial silver toilet service marked by the Huguenot goldsmith Daniel Garnier, circa 1698–99, consisting of a jewel casket, pairs of scent bottles, ecuelles and stands, matching boxes and a silver framed mirror engraved with the coat of arms of Fox and Strangways conjoined.[6] Yet Susannah Strangways Horner allegedly bullied her husband Thomas into an early grave in 1741. She commissioned silver for various parishes on their estate from the leading Huguenot goldsmith Paul de Lamerie. This includes a set of chalice, paten and flagon supplied in 1737 for the parish church of St Michael’s Stinsford which retain their original fitted oak box. Each piece is inscribed ‘The Gift of Mrs. Strangways Horner to ye Church of Stinsford in Dorsetshire in 1737’. The box contained a note dated June 1737 headed ‘Directions to keep the Gilt Plate clean, from the Silversmith that made it’ which read ‘clean it now and then with only warm water and soap, with a Spunge, and then wash it with clean water, and dry it very well with a soft Linnen Cloth, and keep it in a dry place, for the damp will spoyle it’. The other parishes who similarly benefited from her patronage were St Nicholas, Abbotsbury; St Andrew, Mells; St Osmund, Melbury Osmund and St Mary, Melbury Sampford (Nightingale, 1889).

Ironically, the remarkable royal silver-cased clock, presented to Mrs Strangways Horner three years later by Lady Archibald Hamilton in her official capacity as Lady of the Bedchamber to Augusta, Princess of Wales, may well have suffered specifically as a result of the advice on care given by Paul de Lamerie. The steel parts in the watch movement have become rusted, almost certainly owing to exposure to ‘warm water and soap’ during cleaning (the damaged steel parts of the movement have now been cleaned and stabilised as well as possible).

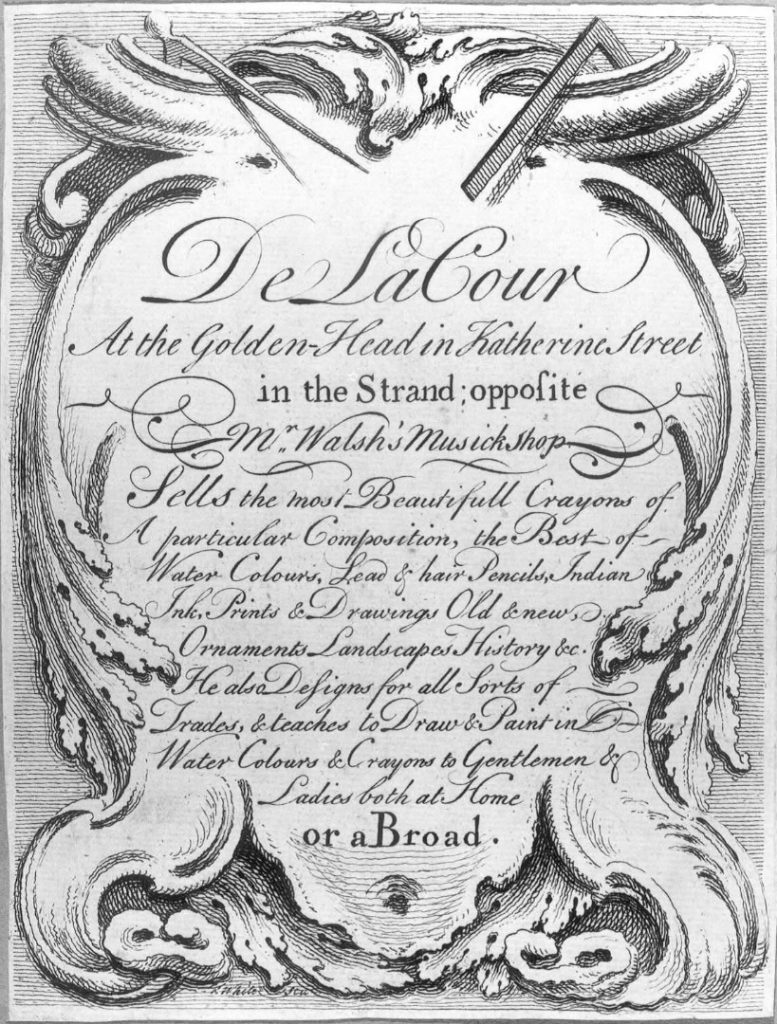

Who supplied this unusual small silver clock case? Its design is in the high rococo style associated with engraved ornament prints published in London and Paris in the 1730s and 1740s and engraved by J B C Chatelain (see Figure 10) and Antoine Aveline after Mondon (see Figure 11). The design of the case and figurative support combine two different ornamental sources. Contemporary freelance designers include William de LaCour, a drawing master with premises in The Strand whose trade card noted that he ‘Designs for all Sorts of Trades’ (see Figure 12). Like the sophisticated mantel clock supplied by royal jeweller Peter Dutens to Frederick Prince of Wales in August, 1736, possibly intended as a wedding present for his bride (Murdoch, 2017), the chased festoon of flowers which adorn the sail-like frame for the dial are identifiable as auricula, convolvulus, jasmine and roses; as discussed earlier the helmeted figure who propels the shell-like boat forward with a staff or paddle was likely copied from a print source (see Figure 13), and was perhaps intended to epitomise the role of Princess Augusta as patroness of the arts and the sponsor of this particular gift.

It is not possible to establish the exact occasion for this gift, but the accounts for Princess Augusta’s Privy Purse, preserved in the Royal Archives, include payments to London retailing jewellers Dutens and Lacam in 1740–1741.[7] This is likely Isaac Lacam, recorded as a jeweller at the sign of the pearl in Buckingham Street, off the Strand, from 1733–1744.

Two further account books of Princess Augusta covering the period 1736–1743 include additional payments to Lacam and Dutens;[8] The payment to Peter Dutens of £100 in August 1740 is the closest in time to the gift of the clock to Mrs Strangways Horner, recorded on the inscription as made in September 1740.

Peter Dutens enjoyed a close financial relationship to both the Prince and Princess of Wales; he received £4,000 from the Prince in June 1741, a further £400 in September 1742 as ‘on bond per warrant’; and a further £3,000 on 2 January 1745 described as ‘bill principal of adjusted accounts’. Isaac Lacam is described in the Archives of the Duchy of Cornwall as ‘jeweller to the Princess of Wales’. These jewellers subscribed to bonds in favour of the Prince’s household which helped to finance his royal patronage. Of some £24,000 in bonds, Dutens and Lacam subscribed the largest amounts; Lacam subscribing £1,500.

Peter Dutens’ trade card (Figure 14) advertised in English and French, gold and silver toys, snuff boxes, jewellery and silver plate from his premises at the sign of the Golden Cup, Chandos Street, St Martin’s Lane. By 1736 Dutens had moved to Leicester Fields closer to Leicester House where Frederick and Augusta established their London home in the 1740s. Dutens was a retailing jeweller and diamond merchant (Heal, 1935). Of Huguenot origin, he was closely linked to London’s Huguenot communities in the West End and the City. The executor of his will in 1761 was James John Majendie, Minister of the Eglise des Grecs in Hog Lane, Soho. Dutens left a bequest of £100 to the Huguenot charity, the French Hospital, known as La Providence then situated in the parish of St Luke’s Clerkenwell (North, 2007).

The high rococo character of the case echoes another commission associated with the Strangways Horner family on loan for display in the V&A’s British Galleries (Figure 15). This is a remarkable silver-gilt ewer and basin chased with marine imagery and engraved with the coat of arms of Fox impaling Hope for Stephen Fox, from 1741, 1st Earl of Ilchester whose mother Christina was the daughter of Rev Francis Hope. The set may have been commissioned as an addition to the earlier toilet service marked by Daniel Garnier which Mrs Strangways Horner presented to her daughter Elizabeth in 1740; a traditional gift for a young wife. Like the sophisticated silver case for the small clock, neither the ewer nor basin are marked.

Both luxury items demonstrate the high quality of contemporary chasing in precious metal associated with the most expensive gifts commissioned and presented in court circles. When Frederick Prince of Wales recovered from illness, he rewarded the members of his household with gifts; Lord Tankerville received a hunting knife; Lord Baltimore, his Gentleman of the Bedchamber, a pocket book; Lord Townshend, a watch; John Schutz, his Steward of the Duchy of Cornwall, a gold etui; and Lord Hervey, a gold snuff-box bearing the royal portrait (Vivian and White, 2006).

Doubtless, Princess Augusta’s gift of this exquisite silver-cased clock made through Lady Jane Hamilton was intended to mark a similar cause for celebration, possibly unrecorded. This article has endeavoured to explain and describe this remarkable confection first published over one hundred years ago (Jackson, 1911), which deserves to be better known.

Acknowledgements

Nigel Israel; Sebastian Whitestone; Simon Bull

The authors are very grateful to James Nye for kindly visiting to photograph the clock for this article.

This research was first presented as part of a joint syposium between The V&A and The Science Museum entitled Sensing time: the art and science of clocks and watches

Technical appendix

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191110/006The following data is technical information taken from the watch movement during the process of study and conservation. Dimensions of the plates and mainspring assembly provide a record of the frame and power source fitted to the watch. Dimensions and numbers of the train (the series of wheels) and motion work (the drive to the dial) provides the specification of the timekeeping part. These data are useful in a technological assessment of the sophistication of the watch and may provide evidence of the craftsmen involved in its creation. It is hoped that in due course comparisons with similar data taken from other watches will enable more sophisticated conclusions to be drawn about the contemporary London watchmaking industry as a whole.

All dimensions are in millimetres.

Frame

Potence plate diameter: 40.6

Pillar plate diameter: 42.1

Plate distance: 10.2

Note: The underside of the potence plate, close to the counter-potence foot, is marked with a stamped, five-pointed star, significance uncertain, but probably the mark of the movement maker or the watch-finisher.

Power Source

Mainspring barrel diameter: 17.6

Arbor diameter: 4.9

Spring Height: 5.0

Spring Thickness: 0.2

Endless screw set-up wheel: 22 / 7.7

Train (No. of teeth / outside diameter + pinion)

Fusee ratchet: 41 / 13.9 (Fusee of 8 turns)

Great: 48 / 18.8

Centre: 54 / 19.9 + 12 / 5.2

Third: 48 / 15.8 + 6 / 2.5

Contrate: 48 / 14.8 + 6 / 2.4

Balance wheel: 15 / 9.1 + 6 / 2.1

Balance frequency: 17,280vbs / hour

Motion work

Driver (off great wheel): 16 / 6.0

Hour wheel: 48 / 17.6

Hour set wheel: 22 / 11.8

Transmission wheel: 21 / 11.2

Setting wheel: 10 / 5.7

Tags

Footnotes

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text