An overlooked eighteenth-century scrofula pamphlet: changing forms and changing readers, 1760-1824

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191210

Abstract

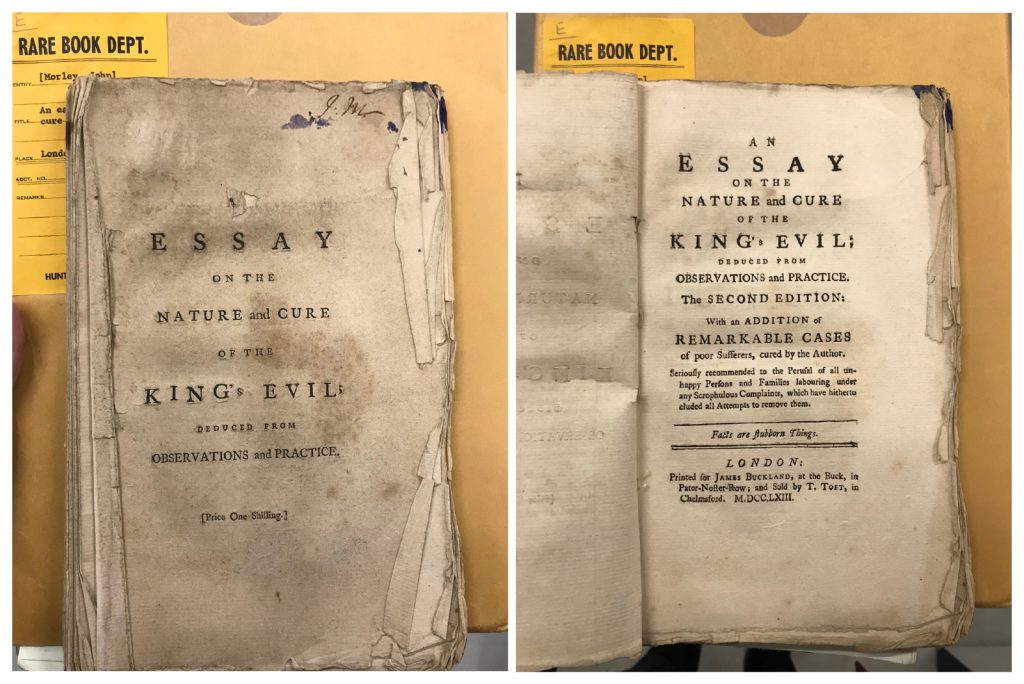

This article tells the story of an eighteenth-century medical pamphlet called An essay on the nature and cure of the King’s Evil, deduced from observation and practice. This was written by John Morley (d. 1776/7), a wealthy Essex landowner who advertised free medical treatments. The pamphlet is one of many short tracts on scrofula produced after the ceremony of ‘the royal touch’ ceased with the death of Queen Anne. However, it merits special attention from historians of medicine and historians of the book because it was edited and reprinted many more times than other surviving scrofula tracts: 42 editions appeared between 1760 and 1824. This suggests significant popularity.

The Essay is also of interest because the first fifteen editions display changes and additions completed by Morley before his death in late 1776 or early 1777. Between these versions, Morley consistently refashioned his identity as practitioner and author. He also adjusted his portrayal of the intended readers of the pamphlet: in later editions, readers are recorded using the Essay in increasingly complex and autonomous ways to design their own medical treatments. The pamphlet is therefore testimony to the fluid relationship between practitioner and patient. It shows that seemingly simple, formulaic and easy-to-read forms like pamphlets and case studies could play a variety of complex and shifting roles in eighteenth-century medical encounters and the construction of healing knowledge.

Keywords

eighteenth century, John Morley, pamphlet, reading, Scrofula

Introduction

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/

How did scientific books – or their authors, printers, publishers and readers – create and communicate knowledge in the era of the hand-operated printing press? Given the sprawling nature of this question, the three centuries it covers, and the fluid meanings of the words ‘science’ and ‘book’, it is unsurprising that historians have approached this question in different ways. For instance, studies of sixteenth-century intellectuals like John Dee and Gabriel Harvey show us that they gained some of their knowledge by spending large amounts of time annotating, excerpting and cross-referencing complex philosophical and scientific works (Jardine and Grafton, 1990; Sherman, 1995; Blair, 2010). But these scholarly books and their scholarly readers only tell us part of the story about how scientific knowledge was created, communicated, remembered and used: for much of the population, that knowledge was transmitted through shorter, more structurally simplistic and apparently ephemeral text-types, such as handbills, broadsides, recipes and pamphlets.

The subject of this article is one such production: an eighteenth-century medical pamphlet on scrofula written by John Morley, a wealthy but otherwise unexceptional Essex landowner. Initially, the pamphlet – entitled An essay on the nature and cure of the King’s Evil, deduced from observation and practice – also seems formulaic and unremarkable. However, a close examination of the forty-two editions and reprints produced between 1760 and 1824 reveals that the pamphlet was actually an eighteenth-century bestseller which played a variety of complex and changing roles in relationships between patients and practitioners. Because its outwardly simple form worked in so many different ways and endured for so long, the pamphlet asks us to rethink our understanding of what a ‘simple’, ‘popular’ or ‘ephemeral’ scientific book was and the ways in which such books could be written and read.

In highlighting the variety of roles that this modest-looking pamphlet played in healing encounters, this article builds on several strands of existing scholarship. Firstly, many detailed studies of early modern and eighteenth-century publishing have emphasised, in Robert Darnton’s words, the complex ‘communication circuit’ at play in the production, dissemination and reception of printed books: authors, publishers, printers, booksellers, and readers all shaped the construction and dispersal of knowledge through the written word (Darnton, 1982). Adrian Johns (1998) and Elizabeth Lane Furdell (2002) have fleshed out these early modern circuits in relation to medical and scientific books specifically. Crucially, Johns reminds us that the fixity which scholars have long associated with the printed book – and which might be seen to inflect the reliability of the scientific claims inside – was actually extrinsic to the books themselves; the idea of fixity had to be continually cultivated by booksellers and printers and continually re-recognised by readers.

This acknowledgement of readers’ agency in the construction of scientific knowledge has dominated late twentieth-century scholarship. Scholars such as Nicholas Jewson (1974), Roy Porter (1985), Joan Lane (1985) and Wayne Wild (2000) have shown that many patients (large numbers of whom were also readers) possessed sufficient medical knowledge and social authority to describe and diagnose their own symptoms to practitioners, thereby controlling medical interpretations of their ailing bodies. Similarly, Carlo Ginzburg (1992) and Mary Fissell (1992; 2003) have shown that individual readers from diverse social backgrounds extracted their own – sometimes perverse or counterintuitive – meanings from astrological writings, almanacs and sex manuals; no single mode of knowledge construction could be enforced by the text or its author. Furthermore, many readers exercised admirable skill even when interpreting apparently simple or formulaic medical texts: Wendy Wall (2015) and Elaine Leong (2013; 2014; 2018) have demonstrated that decoding, summarising, verifying and rewriting household recipe books involved impressive levels of evaluation, comparison and discernment. Similarly, Jennifer Richards (2012) has shown that sixteenth-century English regimen often contained contradictory pieces of lifestyle advice from various medical authorities which readers then had to choose between for themselves. Even eighteenth-century newspaper adverts for patent medicines required readers to diagnose themselves independently as in need of a particular treatment before they could respond positively to an advertisement (Forman Cody, 1999, pp 109–110). Readers were a vital and active part of communication circuits.

John Morley’s pamphlet, which has been entirely overlooked by scholars, is a particularly valuable case study for exploring the range of roles that authors and readers played in these communication networks. This is because, in its initial sixteen years of publication, Morley continually revised and rewrote the pamphlet; the first edition was published in 1760 and the fifteenth edition was published shortly before Morley’s death in late 1776 or early 1777. The alterations Morley made to these initial fifteen editions reflected, responded to, and brought about changes in his relationship with the pamphlet’s readers. They can be roughly grouped into two phases: many of the changes to the first ten editions indicate Morley’s ongoing efforts to fashion an identity for himself as an authoritative and altruistic amateur practitioner; he suggests various ways that readers can use the pamphlet to access his expertise in person. In the final five editions, or second phase, this self-fashioning is still present but Morley starts to represent his readers differently: he records them using the pamphlet in more complex, remote and autonomous ways and he adds navigational tools to facilitate such engagements; the roles of patient and practitioner become increasingly blurred. Analysed together, then, the first fifteen editions map a multitude of ways in which patients and practitioners could engage with one another, and with print, as they created, confirmed, communicated and revised medical knowledge.

Uncovering these relationships compels us to reassess initial impressions of the pamphlet as simply constructed, easy to read, and ephemeral: readers invested significant amounts of time extracting information from it and Morley spent an unusual amount of time revising and updating the text with the result that it endured long beyond his own lifetime. After his death, the pamphlet was reprinted in new numbered editions for the next 48 years. The structure of this article will reflect that chronology: after a brief introduction to the historical backgrounds informing the Essay, the first three parts of the article explore the changes Morley made during his lifetime. In these sections, the copies of the seventh and fifteenth editions owned by the Science Museum inform my close analysis of the pamphlet’s material form. The final part of the article then extends this material emphasis by exploring the pamphlet’s afterlife: how did readers – existing in the real world and not just represented in the pamphlet itself – read, annotate, and use their copies? Here I acknowledge that the pamphlet cannot be wholly subordinated to a neat chronology: although the changes Morley made to the pamphlet unfolded through time and often suggest a forward movement towards particular goals, readers consulted older and newer editions with their own diverse motivations in mind.[1]

Historical contexts

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191210/002Before analysing the many versions of Morley’s Essay, it is important to provide a brief overview of the historical contexts informing the pamphlet in order to indicate how typical or atypical it was. Firstly, the subject of the Essay is scrofula, an affliction characterised by large swellings of the lymph nodes. We now know that the swellings can be caused by the same mycobacteria responsible for tuberculosis. In the eighteenth century, however, there was less consensus over scrofula’s causes and the affliction could prove fatal if it led to festering ulcers and amputations. Even in non-fatal cases, the swellings and deformities the infection produced were likely to have been socially debilitating, especially for the young who have always been – on account of the way the lymphoid system develops – more susceptible to lymphadenopathy (Cohen, Powderly, Opal, 2010, p 164). Morley’s experiences reflected this; he added a table to the eighth edition of the Essay which described the age and sex of two thousand of his patients: most were under thirty (1363) and the majority of these were female (800) (Morley, 1772, p 57). These young women perhaps suffered more severe social consequences from the cosmetic damage scrofula wrought.

Morley’s pamphlet was published several decades after a turning point in scrofula’s history. From the Middle Ages through to the death of Queen Anne in 1714, scrofula was treatable through ‘the royal touch’: this was a large and carefully staged ceremony, in which patients who had exhausted all natural remedies could have their swellings healed by the divinely anointed hands of the English monarch (Brogan, 2015, p 60). This is how scrofula became known as the King’s Evil. After Queen Anne’s death, however, the Hanoverian monarch, George I, discontinued this miraculous healing ceremony, possibly because of its Catholic and Stuart associations (Brogan, 2015, pp 204–5). So, although natural remedies for scrofula had always been advocated, they acquired a new significance after 1714. There were certainly many texts advertising them at the time of Morley’s Essay but, judging by the smaller number of editions produced, none seems to have been quite as steady a seller.[2] Historians of medicine have paid little attention to these eighteenth-century writings, focusing instead on the social, political and religious implications of the royal touch (Bloch, 1961; Crawford, 1977; Levin; 1989; Turrell, 1999; Brogan, 2015).[3]

Many of these overlooked eighteenth-century texts on scrofula were issued as pamphlets; indeed, Morley (1776, p 83) describes his Essay as a ‘Twelve-Penny Pamphlet’. What would this label have signalled to eighteenth-century readers? Pamphlets were defined for taxation purposes by the 1712 Stamp Act as books which did not exceed 96 pages when produced in octavo format (Raymond, 2003, p 82; Bayman, 2016, p 6). However, they could also be produced in quarto and were usually sold unbound with the pages simply stitched together. They were thus characterised by being small, thin, and cheap to produce and many were accessible to a broader cross-section of the population than other kinds of books (Halasz, 1997, pp 16–17). This market appeal made pamphlets a popular form for writers, printers and booksellers, who did not need to risk large investments of time and money in their production. In fact, printing and re-printing pamphlets that were proven bestsellers could provide booksellers with enough financial security to stock more costly volumes (Bayman, 2016, p 7).

Seventeenth-century pamphlets associated with topical social issues and political controversies have been well-studied. Although eighteenth-century pamphlets have been discussed in large-scale publishing studies (e.g. St. Clair, 2004, pp 256, 277–78, 309, 562), less scholarship has been devoted solely to them; this is despite the fact that production of all types of books and pamphlets soared in the second half of the eighteenth century due to growing demand, improved distribution networks and increased organisation within the bookselling trades (Raven, 2007, 130–31). Medical pamphlets and the ways in which readers engaged with them have been particularly understudied, though there have been a few in-depth analyses of particular writers, controversies and styles (e.g. Newman, 1994; Fissell, 2007, pp 120–27). Furthermore, recent work on other ephemeral medical forms, such as handbills (Guerrini, 2010) and advertisements (Forman Cody, 1999; Barker, 2009; Strachan, 2007; Mackintosh, 2017), has developed important insights into the ways that trust and authority were cultivated and the ways that academic discourse interacted with more widely accessible medical ideas. These studies all provide useful models for approaching Morley’s pamphlet.

Another useful model is Deborah Madden’s study of John Wesley’s eighteenth-century pamphlet, Primitive Physic; Or an Easy and Natural Method of Curing Most Diseases. This was a short compendium of medical recipes for healing all kinds of ailments (Madden, 2007). John Wesley had much in common with Morley: he did not have a formal medical qualification; his professed reason for publishing the pamphlet was to help the poor, and his recipe collection shared a practical and therapeutic emphasis with later versions of Morley’s Essay, allegedly providing simple, homely cures that even poor labourers could make. As Madden (2007) has shown, however, Wesley’s reading and intellectual influences were wide-ranging; Morley’s engagement with academic writings (discussed below) might seem similarly surprising given that – like Wesley – he was associated by his opponents and critics with anti-intellectual, folk remedies. Both texts therefore show us that academic discourse could inform even the simplest, most widely accessible writings: both were pocketsize and concise and were advertised at the same affordable price of one shilling.

Like Morley’s pamphlet, Primitive Physic stands out from similar titles because it went through many more editions: 23 editions were produced during Wesley’s lifetime and the 37th and last edition was produced in 1859, over one hundred years after the first edition was published (Madden, 2007, p 11). Like Morley, Wesley was assiduous in tweaking and updating his text across these editions, correcting errors and adding new recipes. The ease and cheapness with which pamphlets could be revised and reprinted was probably a large part of their appeal for both authors: it meant that knowledge could be supplemented; reader and reviewer feedback could be incorporated and, as we shall see, authorial identity could be continually refashioned. It probably also contributed to the pamphlets’ ongoing appeal to buyers: title pages advertising a ‘new’ or ‘revised’ text could convince readers that they were purchasing cutting-edge knowledge. The comforting familiarity of the author’s name by later editions possibly also served as a stamp of authority.

But pamphlets had negative associations as well: the rapidity with which they were printed and written meant they could be associated with sloppy writing skills, a lack of intellectual rigour and demeaning commercial motivations (Bayman, 2016, pp 13–15, 19; Raymond, 2002, pp 7–11). Pamphlets advertising medical services and products were especially susceptible to negative associations with ‘quacks’: as Roy Porter has shown, this capacious term of abuse was often deployed in eighteenth-century polemic to describe practitioners – both educated and unlearned, qualified and amateur – who used wide-reaching printed forms such as pamphlets, broadsides and newspapers to sell inefficacious cures to gullible patients (Porter, 1989, pp 1–20).[4] Harold Cook (1986, p 43) suggests that, compared to broadsides, pamphlets were considered a more respectable medium for eighteenth-century orthodox physicians: they were more informative and less obviously commercial. But the concerns associated with any kind of mass publishing still affected pamphlet writers: William Vickers, the author of another eighteenth-century pamphlet on scrofula, expressed such unease when he proclaimed that ‘this way of publishing Medicines and Cures is now esteemed Quackism…’ (Vickers, 1709, p 11).

Because of these associations, readers of medical pamphlets also risked being denigrated as gullible and naive; pamphlets on all subjects had long been belittled as ‘toyes, trifles, trash, [and] trinkets’ (Greene, 1583, sig. A3; Bayman, 2016, p 15). In their attempts to move beyond such polemic, and discover the diverse ways in which readers actually engaged with pamphlets and other small books, scholars have been hampered by a lack of evidence: many copies of these books do not survive and those which do frequently contain no material traces of readers’ engagements with them (Fissell, 1992, p 88). This is another reason why John Morley’s pamphlet – and the significant number of copies surviving in repositories around the world – are so valuable: not only do some copies survive with annotations, but the testimonials Morley includes in later editions contain information from readers about how they extracted information from the pamphlet. As we shall see, these show that even short, seemingly formulaic texts could invite a variety of complex reader responses.

Initial experiments, 1760–63: the first and second editions of the Essay

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191210/003

Morley published the first edition of his Essay in 1760 and the second edition was published three years later. Outside the contents of the pamphlet, we know little about Morley beyond the fact that he was the grandson and heir of a prosperous land agent who rose from humble origins as a butcher to become the land agent of Josiah Child (director of the East India Company) and Robert Harley (English Prime Minister) (French, 2000, pp 44–66). This inheritance left Morley with substantial wealth and, when he died, he left over £12,000 to his three youngest children and their heirs, before bequeathing all of his land to his eldest son.[5] There is no evidence, though, that this impressive wealth gave Morley access to any formal medical training; he admits in the Essay that he is ‘no Physician, Surgeon, or Apothecary’ (Morley, 1760, p viii). However, such wealth probably did give Morley the leisure and financial security to write fifteen versions of his pamphlet. He might even have financed these editions himself; in the eighteenth century, pamphlets were often printed at the expense of their authors (St. Clair, 2004, p 562).

Like all of the editions printed in Morley’s lifetime, the first two editions were published in London by an eighteenth-century bookseller called James Buckland (Heal, 1951). Between 1736–41, Buckland resided at a partitioned shop (now referred to as 14a) in London’s Paternoster Row; he then moved to number 57 on the Row, where he was succeeded after his death in 1790 by George Wilkie, the publisher of later editions of the Essay (Raven, 2007, p 177). Paternoster Row was one of the most prominent areas for booksellers in the eighteenth century and Buckland seems to have had a long and respectable career there; his will shows that he left an allowance of forty pounds a year to his son.[6]However, Buckland’s shop – positioned in the south-eastern quarter of the Row – was situated in an area dominated by old-fashioned publishers and less notable names; indeed, Buckland is remembered in Charles Timperley’s Encyclopaedia of Literary and Typographical Anecdote as an ‘old fashioned gentlemanly type of bookseller’ (Raven, 2007, p 177). Was it this gentlemanly demeanour that recommended Buckland to the Essex-based Morley? Perhaps. However, the alliance was more likely the result of Buckland’s own ties to Essex. Before moving to London, Buckland published books in Chelmsford[7] and he maintained connections there: the first two editions of the Essay list Timothy Toft, a Chelmsford bookseller, as the local seller of the pamphlet. This arrangement was probably fostered by family relations: for part of his publishing career, Toft was the partner of Richard Lobb, Buckland’s nephew by marriage (Plomer, 1968, p 246) The Lobb family also connected Buckland to medical matters: his wife, Elizabeth Buckland, was the niece of Theophilus Lobb, a physician and published medical writer who had patented a medical tincture; he left the proceeds from the sale of this tincture to Elizabeth (Goodwin and Payne, 2004). There was, then, a strong network of familial connections linking Buckland to Essex and to medical matters, and making him an appropriate publisher for Morley’s Essay.

Both of these first two editions of the Essay were printed in octavo but the title pages differ in several respects: in the first edition, the pamphlet is obscurely attributed to ‘a private Gentleman of Halstead in Essex’ but in the second edition, no author is mentioned. It seems Morley – who is eventually identified at the end of the preface – wished to cultivate a sense of mysterious anonymity. The second difference concerns cost: the price of the first edition is listed as six pence, whilst the price of the later edition is recorded on an outer wrapper as one shilling. This increase can be partly justified by the fact that the second edition is over thirty pages longer, containing an added set of case studies recording the details of patients whom Morley had successfully cured; the second edition therefore required more paper and ink and more expense.

Beyond these differences, the pamphlets are almost identical in content: both contain a preface in which Morley claims that his cure for scrofula was inherited from a female relative who also used it to treat the poor (Morley, 1760 and 1763, pp iii–viii). Similar attributions of cures to female healers occur in many early modern medical writings and in several other scrofula texts.[8] These narratives – which hover indeterminately between historical plausibility and trite convention – were probably intended to capitalise on female associations with beneficence, domesticity and nourishment; as multiple studies of seventeenth and eighteenth century women have shown, charitable healing was a significant part of upper-class identity formation and network building (Vickery, 1998, pp 153–56; Pollock, 1993; Hole, 1953, pp 79–98). The repetition of this trope might have made the Essay seem tired and unimaginative to some readers, but to others it could have endowed the pamphlet – and the medical knowledge inside it – with a sense of timeless wisdom.

Given this prefatory narrative of a secret remedy passed down through generations, it is surprising that neither of these editions of the Essay actually contain any information about a cure for scrofula: both versions are – somewhat anti-climactically – devoted to discussing the causes of the affliction. Even the reports of successful cases included in the second edition contain no information about the actual treatments Morley used on his patients. This omission increases the sense of mystery surrounding the inherited cure. Meanwhile, Morley’s dissection of scrofula’s causes enables him to display his learned familiarity with chemical and mechanical medical theories: he attributes most scrofula cases to the increased presence of alkaline salts in the blood and argues that, because these salts can be particles of irregular shapes and sizes, they cause obstructions in the glands, the ‘Strainers of the Body’ (Morley, 1760, p 19). These blockages separate red globules (the fibrous part of blood) from the serous part of the blood which carries the globules around the body. The red globules, which are no longer interspersed with the serous part of the blood, obstruct the body’s spirits, putrefy and turn into pus. At the same time, distended glands and build-ups of the serous part of the blood produce tumours and ulcers, the characteristic symptoms of scrofula (Morley, 1760, pp 19–21).

In this account, Morley cites several well-respected, academically qualified scientific authorities. Sometimes, his engagements with these writers are fleeting; they appear merely as namedropping exercises designed to showcase his learning and the importance of his secret cure. For example, he refers briefly to writings about scrofula by Sir Richard Blackmore (1654–1729) and Charles Leigh (1662–1701?), both of whom were university-qualified physicians and Fellows of the Royal Society (Gregori, 2004; Sutton and Bevon, 2004). Morley interprets Leigh’s desire for ‘some specifick’ to cure scrofula as evidence that ‘the Nature and Cure of this Disease was very little known by any of the Faculty in his Time’ (Morley, 1760, p 16). He then cites Blackmore’s comments on the difficulty of untangling the symptoms of scrofula from those of other diseases; this, Morley claims, ‘strengthens Dr. Leigh’s Observations of the small Progress that has been made in the Nature and Cure of the King’s Evil’ (Morley, 1760, pp 16–17). Morley presents both of these academic medical authorities as outdated, of their time, and unable to see a way forward in the treatment of scrofula. His remedy, the pamphlet implies, has relieved such blindness.

Given this progressive chronology, it is ironic that Morley’s own medical theory may have seemed outdated at the time he was writing. For instance, he explains that his conception of the alkaline composition of the blood was influenced by Robert Boyle’s Memoirs for the Natural History of Humane Blood (1684) (Morley, 1760, pp 11–12). As scholars have noted, Memoirs for the Natural History of Humane Blood was already outdated when Boyle published it: it was composed from findings that were two decades old and it failed to take note of new research on the structure of the blood by scholars such as Antoni van Leeuwenhoek and Walter Needham (Hunter and Knight, 2007).[9] Morley may have been aware of this particular shortcoming: his claim that the fibrous part of the blood consists ‘of great Numbers of fine smooth red Globules’ recalls van Leeuwenhoek’s 1674 description of red blood cells under the microscope (Morley, 1760, p 18; Hunter and Knight, 2007, p 160).

On the whole, though, Morley was not very assiduous in updating his citations; unlike John Wesley, he did not update each edition in relation to new medical findings (Madden, 2007, p 269). For instance, Morley cites Observations of various eminent cures of scrophulous distempers commonly call’d the King’s Evil (1712) (Morley, 1760, p vi).

This tract was written by James Gibbs, a student at Oxford University and, later, a practising physician. Like Morley, Gibbs was an advocate of a form of iatrochemistry which explained diseases through the proportion of acids and alkalis in the body. This body of thought, which extended the chemical ideas of Paracelsus and Jan Baptist van Helmont, was developed in the second half of the seventeenth century by individuals such as Franciscus Dele Boë Sylvius and Herman Boerhaave. In the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, acids and alkalis remained central to medical theories, but established iatrochemical ideas were modified by Newtonian ideas about gravity, attraction between matter and the movement of fluids through the body; they were also modified in the second half of the eighteenth century by a move back from mechanism to vitalism and by new ideas about contagion (Roos, 2007, pp 108–54; Guerrini, 1985; DeLacy, 2017, pp 19–54). As Anne Marie Roos (2007, pp 158–63) notes, James Gibbs’ tract was already outmoded when it was published in the early eighteenth century because Gibbs did not engage with Newtonian ideas, but continued to explain scrofula through a combination of astrological influence and increased acidity. Morley seems similarly outdated for the late eighteenth century: although there is a fleeting reference to Newtonian ideas of attraction, his corpuscular, iatrochemical explanations do not include any detailed engagement with Newtonianism, vitalism or contagionist theories.[10] His citations of Boyle and Gibbs also indicate that his writing was more closely connected to the academic conversations of the late seventeenth century than the late eighteenth.

There is no evidence, though, that Morley considered his Essay old-fashioned and only intellectually up-to-date readers would have recognised it as such. Other lay readers probably took at face value Morley’s portrayal of himself as a mediator of current academic knowledge: after assuring readers that he will not use ‘hard Words, or technical Terms of Art, to puzzle and confound [them]’, he is careful to explain difficult terminology (Morley, 1760, p viii). For example, he likens the corrosion of human bones by alkaline salts to the salting ‘of raw Beef […] in the Pickling Tub’ (Morley, 1760, p 14). In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, information ascribed to academic authorities was continually being reinterpreted in new, more accessible contexts: for instance, Anita Guerrini (2010) has shown that broadsides advertising displays of human ‘monstrosities’ were influenced by learned anatomical discourse. Similarly, Wendy Wall (2015, p 222) and Lynette Hunter (1997a, pp 89–107; 1997b, 191–94) have demonstrated that seventeenth- and eighteenth-century owners of household recipe books cited and evaluated Robert Boyle’s experiments. Indeed, in a catalogue of books owned by Morley’s notorious land agent grandfather, the first text listed is ‘Boyle’s Experiments on Cold’ (A Catalogue of valuable English books…, 1733, [p 3]). Morley’s pamphlet may well have been aimed at this kind of lay audience: an audience of upper-class amateur intellectuals who – like Morley – did not possess any formal academic qualification but had the leisure and financial resources to pursue their scientific interests. These readers should not automatically be labelled as passive recipients of simplified – or ‘popularised’ – academic knowledge; scholars have shown that, instead of a top-down trickle of knowledge from academic authorities, there was often a more complex exchange of ideas occurring between different social groups (e.g. Jewson, 1974; Porter, 1985; Smith, 1985; Wilson, 1992; Fissell, 1992). Later sections of this article will also show that the assimilation of knowledge by lay readers was an active and skilful process.

Intriguingly, though, these amateur intellectuals are not the audience to whom Morley explicitly directs the Essay: instead, the title page of the second edition claims that the pamphlet is ‘seriously recommended to the Perusal of all unhappy Persons and Families labouring under any scrofulous complaints’ (Morley, 1763). How, though, were these scrofulous patients to derive any benefit from a text that did not describe a remedy? What good would an aetiological discussion of scrofula have done them? Morley justifies the omission of his remedy in the following way:

It may be asked, why I don’t publish my own [cure] […]? To such Enquirers I answer: The Medicines I use are very innocent and common Things, but the Preparation is curious and difficult, and takes much Time to compleat […] as the common Labourers, and Handicraftsmen, their Wives and Children, make the Bulk of my Patients, it is above their Capacity, and of no Use to tell them any Thing about it, more than what is necessary […] and to give them the plainest and simplest Directions possible.

If practical instructions really were ‘above [the] capacity’ of this group of patients, then Morley’s aetiological explanations – however simplified – also would be. Perhaps, these first two editions were actually intended by Morley (and his commercially-minded bookseller) to function more as advertisements than self-help guides: if readers saw the word ‘cure’ on the title page, they might be persuaded to buy the pamphlet without realising that it did not contain a remedy. They could use the pamphlet to diagnose their own symptoms as scrofulous but, once they realised the cure was missing, they would need to seek Morley out and employ his medical expertise in person. Harold Cook has observed that many practitioners employed this advertising technique: Nicholas Sudell, the seventeenth-century author of Mulierum Amicus: Or, The Woman’s Friend (1666), gave directions on making medicines for female ailments before claiming that, if these proved ineffective, he had many secret remedies for sale in London (Cook, 1986, pp 43–44). Mary Fissell (2007, p 126) suggests that such pamphlets served a dual purpose: they ‘were neither purely informational nor purely promotional but an extremely successful hybrid of the two’. A similar blend has been observed in eighteenth-century newspaper advertisements by Alan Mackintosh (2017, p 207): the authors of these adverts used measured lists of facts about a patent medicine, its creator, and use to convince buyers of its trustworthiness. Morley applied the same techniques to his person: by showing his understanding of medical theories and physiology, he could convince readers that he was an educated practitioner worth trusting.

It may seem odd to associate Morley with advertising: his wealth meant that he had no obvious need to puff his medical services but – unlike most pamphlet writers and sellers of proprietary medicines – could offer them for free (Morley, 1760, p viii). Simon Shapin (1994, pp 83–84) has argued that gentlemanly disinterestedness was used in early modern academic circles to cultivate a sense of unbiased scientific authority; the logic underpinning this intellectual privilege was that those in secure social and financial circumstances had no need to falsify their scientific findings; they could share reliable information freely and for the public good. Morley’s pamphlet may have been interpreted in these disinterested charitable terms; perhaps he only concealed his free cure because he genuinely believed that he could offer patients better care in person than any self-help pamphlet. But, lacking any formal qualifications, he may also have advertised his services in order to bolster his reputation and intellectual credentials. Susan Lawrence (1996, pp 36–38), Sandra Cavallo (1991) and Alan Mackintosh (2017, pp 91–97) have stressed the difficulty of unravelling the motivations of charitable acts in the past, arguing that self-interested motives concerning reputation and money need not always have cancelled out more benevolent medical aims. We should be aware, then, that the ‘medical marketplace’ was not just a market where patients and practitioners negotiated economic circumstances, but a space where economic considerations interacted in complex ways with social factors like reputation and altruism (Jenner and Wallis, 2007).

We also need to remember, though, that eighteenth-century readers did not always interpret those intersecting factors in a nuanced way: a reviewer from the periodical The Critical Review was clearly sceptical about Morley’s altruistic aims. The unnamed author of this scathing response to the Essay may have been Tobias Smollett, satirist, surgeon and editor of The Critical Review until 1763 (Simpson, 2008):

We know not whether the author’s evil or the king’s evil be the most disagreeable distemper: but both are said to be cured by the royal touch, which, for our sakes, we could wish applied to this writer, that his discharge may be stopped. All we can learn from this benevolent address is, that Mr. Murety,[11] Gentleman of Halstead in Essex, is possessed of a specific against the king’s evil, the secret of which he had communicated to him by a lady of his family. This arcanum he is determined to keep in the family, thereby to raise its importance […] What Pity the world should ever be deprived of so humane and benevolent a citizen!

Making full use of the association between scrofulous ulcers leaking pus and excessive verbal discharge, this reviewer suggested that Morley selfishly concealed his cure in order to increase its perceived value and boost his own reputation. Morley is here cast in the role of a fame-hungry charlatan. His early attempts to fashion himself as a well-read, authoritative, altruistic practitioner do not seem to have been unanimously convincing.

The middle editions, 1766–74: a self-help guide?

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191210/004Negative reviews frustrated Morley: in the third edition of the Essay, published in 1766, he writes that he has not written the pamphlet ‘to tickle the Ears, or please the Palates of the censorious Readers or mercenary Reviewers, who find fault with what they do not understand’ (Morley, 1766, p v)). Here, Morley turns the tables on the above reviewer (whom he cites in a footnote), reframing the reviewer as the commercially motivated one, rattling out misguided reviews for money. Nevertheless, Morley heeded that reviewer’s advice, demonstrating just how pivotal a role readers played in the communication circuits shaping printed books: the so-called ‘third edition’ of the Essay bears the same title as the first two editions, but it is a completely different text, allegedly aimed at a different readership. Morley describes this shift in the text’s new preface:

Being daily importuned not to let the Method [of curing scrofula] die with me, I some Years ago published two Editions of this Essay to let poor Sufferers know where to apply for Advice (gratis), but did not tell them any Receipts for the Distemper; I shall now publish those Methods and Things, that the common People can easily procure, and safely apply [them] […] I do not (in this Essay) pretend to inform the Learned in the Management of Scrophulous Disorders, who are supposed to know them much better than I do; but only, to instruct the plain honest Artificers and Labourers…

The text is no longer an explanation of the causes of scrofula, but a guide to curing it. With its new practical emphasis, Morley’s text resembles contemporary pamphlets such as John Wesley’s recipe collection Primitive Physic (1747) or the six-penny self-help guide, A cheap, sure and ready guide to health; or, a cure for a disease call’d the doctor (1742), which was funded by another ‘private gentleman’ with ostensibly altruistic aims. Morley contrasts the new readership of his self-help guide against that of the previous versions: he confirms that the first and second editions were designed to function as advertisements, ‘let[ting] poor sufferers know where to apply for Advice’. His careful stipulation that he does not intend to ‘inform the Learned’ in ‘this Essay’ is also a potential acknowledgement that those earlier editions – theoretical and allusive in style – were partly aimed at a more intellectual audience. In contrast, this third edition is aimed at instructing ‘the common people’, the craftsmen and labourers, how to cure themselves. A new readership of self-healers is evoked and the relationship between patient, practitioner and pamphlet is reconfigured.

This readership may not, though, have been quite as inclusive as Morley claims. Not all labourers would have possessed the necessary literacy skills to read the Essay, although there were many ways for eighteenth-century people to engage with texts orally and communally (Cowan, 2012; Shepard, 1973). A second potential difficulty would have been the cost of the Essay. At one shilling, it was relatively cheap for a pamphlet and it was cheaper than the ready-made medicines advertised in newspapers, many of which cost between one and five shillings.[12] But it still would have amounted to a day’s wages for an eighteenth-century labourer (Hume, 2014, p 385). For craftsmen, the pamphlet would also have been a relatively pricy investment, accounting for roughly half of their daily income (St. Clair, 2004, p 40). It seems likely, then, that Morley’s targeting of common labourers and craftsmen was in part a rhetorical gesture aimed at underlining (and exaggerating) the new openness of his Essay.[13]

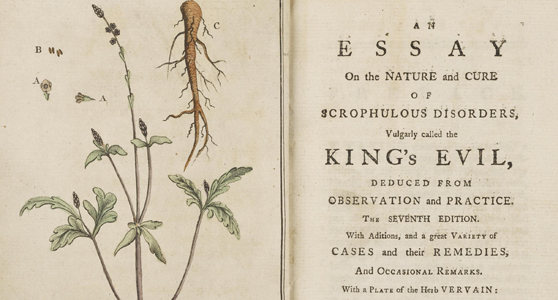

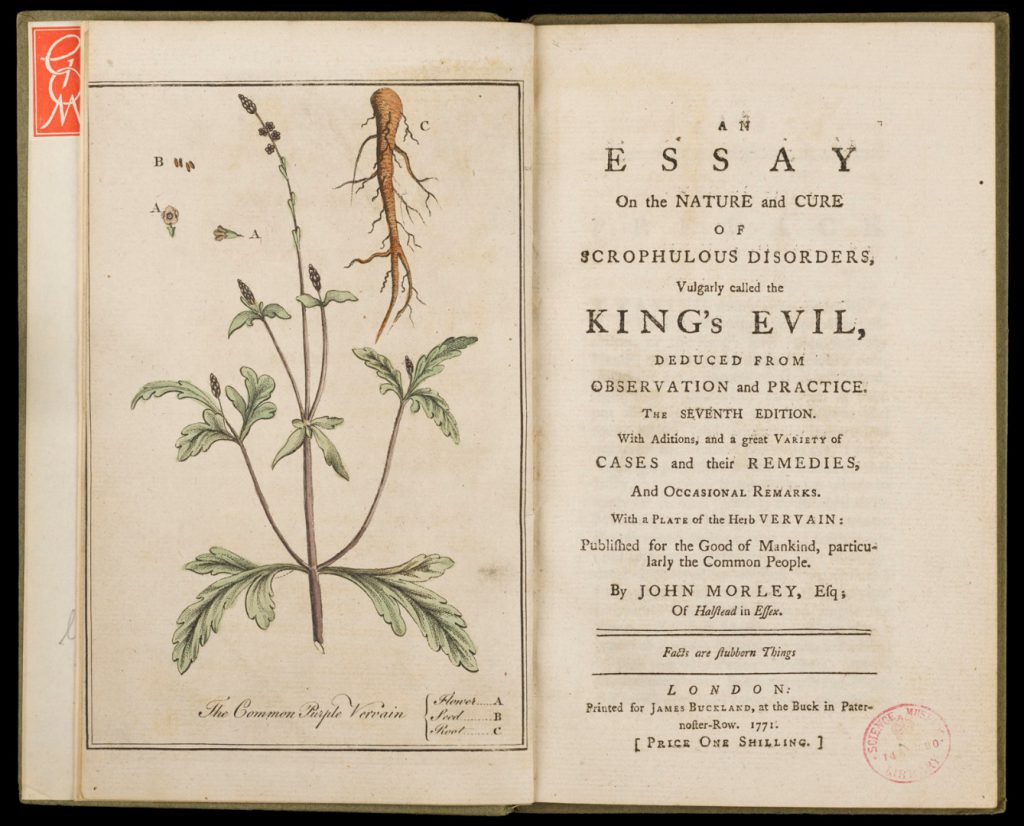

The pamphlet’s design also suggests a socially diverse audience: like the first two editions, the rest of the versions edited by Morley before his death are produced in a small octavo format; the copy of the seventh edition owned by the Science Museum measures 123 mm in width by 207 mm in height. The basic layout of these editions is relatively simple: after an introductory section describing the characteristics of scrofula and Morley’s remedy for it, case studies testifying to successful cures are printed one after the other in a roman typeface on paper of middling quality. But Morley (or his publisher) did indulge in aesthetic flourishes: in the fourth edition (1768), Morley adds an illustrated plate depicting the flower, seed and root of the herb vervain and, from the ninth edition onwards, this is explicitly advertised on the title page as ‘a coloured plate’.

This intaglio print, which is normally inserted opposite the title page, contains no information about its drawer or engraver; like many eighteenth-century botanical images, it may have been copied from another work (Nickelsen, 2006, pp 185–228). In the print, the constituent parts of vervain are rendered through simple outlines; minimal detailing has been added to some of the leaves, the roots, and around the centres of the flowers, but otherwise there is little sense of depth, tone or texture. The quality of the colouring, which varies greatly from pamphlet to pamphlet, can exacerbate this flat, two-dimensional, diagrammatic quality: for example, in the copy of the fifteenth edition owned by the Science Museum, the colouring is far less careful and tonally sensitive than the colouring in the Museum’s copy of the seventh edition (see Figures 4 and 5). This lack of tone and detail means that the print would only have served as a basic guide for readers seeking to identify vervain by its shape and colour; the image would need to be supplemented by the written description Morley provided (Morley, 1766, p 17).[14]

Despite these limitations, Morley and Buckland must have considered the print sufficiently useful or attractive to fund its production; although the quality of intaglio prints could vary greatly, they always necessitated extra expense (Nickelsen, 2006, pp 30, 62). This is because they had to be printed on a separate, rolling press from the rest of the text. The labour for this printing had to be financed and Roger Gaskell (2004, p 222) has estimated that, even without the extra costs of engraving and colouring, adding a newly made plate to a print run of 500 quarto copies of thirty sheets would raise overall production costs by five per cent. It is therefore surprising that the addition of the illustration – however simply or cheaply executed – did not push up the price of the one-shilling pamphlet. Perhaps Morley provided the extra funding in another charitable act designed to spare his less affluent readers any additional expense. This benevolence may have brought its own reward, with the hand-coloured print appealing to a more refined, aesthetically conscious readership. It would, after all, have been the middle and upper classes who were comfortably able to afford the one-shilling pamphlet.

Vervain is depicted in the plate because it is the central component of Morley’s newly revealed remedy: he begins treatment by hanging around the patient’s neck a fresh root of vervain on a white ribbon. Morley acknowledges in the earlier editions that this treatment is a refined version of an older remedy and this explains why variations of it appear elsewhere: for instance, John Quincy’s 1724 Complete English Dispensatory records an old remedy for scrofula which involves hanging a vervain root around the neck (Quincy, 1724, p 145; Morley, 1760, p vii).[15] Morley’s remedy is also a pastiche of the royal touch: when monarchs were touching patients afflicted with the King’s Evil, they used to hang a gold coin – known as an ‘Angel’ – on a white ribbon and place it around the patient’s neck (Brogan, 2015, p 3). Morley probably deployed the iconography of this renowned ceremony in order to instil confidence in his plant-based remedy. However, from the fourth edition of the text onwards, he was careful to provide a technical-sounding, chemical explanation for the ribbon colour, alleging that ‘no other coloured Ribband is proper; because the Dye in some Colours may be prejudicial’ (Morley, 1768, p 14).

Although these middle versions of the pamphlet are far less theoretical than the first and second editions, there are several moments such as this, where Morley is at pains to point out that his cure works through academically acceptable means, rather than any occult or supernatural power. For instance, he claims that, when he places the vervain root around the patient’s neck, he does not utter a prayer ‘by way of Charm, or such like Nonsense, but to remind the Patient of our Dependence on the divine Help’ (Morley, 1766, p 16). Unfortunately, this did not stop the Critical Review ridiculing Morley’s precise choice of ribbon colour and dismissing the vervain roots again as ‘amulets’ (‘An Essay on the Nature and Cure of the King’s Evil…’, The Critical Review or Annals of Literature, 1767, pp 453–54).[16] Through this label, the reviewer returned Morley’s medicine to the status of a ‘charm’ and suggested that there was no credible scientific or religious rationale behind it.

Morley’s root also risked being condemned as a ‘specific’. These were cures made from single substances which were proclaimed capable of curing disorders in any patient through occult natural properties undetectable to the senses (Hunter and Davis (eds), 2000, p 360; OED, ‘specific’, adj. and n., entry 3a). Because they could not be explained through prevailing medical theories and because they challenged the view of academic medicine that each patient’s constitution was different (and therefore required different treatment), specifics could be associated with uneducated quacks.[17] Consequently, in the fourth edition, Morley adds another chemical explanation which renders the healing properties of vervain explicit and understandable: ‘This Plant, by a Chymical Analysis, yields several acid Liquors, abundance of Oil, pretty much volatile concrete Salt and Earth […] It is vulnerary, cleansing, and opening’ (Morley, 1768, p 17). By the sixth edition, he has also added a reference to Robert Boyle’s Of the Reconcileableness of Specifick Medicines to the Corpuscular Philosophy, which explains specifics through an academically acceptable mechanical model (Morley, 1770, p 58; Hunter and Davis (eds), 2000, pp 359–403). Finally, from the fourth edition onwards, these measures are accompanied by unequivocal criticism of those who assume a vervain root will cure any patient, ‘not considering that such various Symptoms, Constitutions, and the different Parts affected […] require very differently appropriated Medicines and Applications’ (Morley, 1768, p 45). This polemic is supported by case studies which record the different substances Morley has combined vervain with for different patients: for instance, Robert Heatherly from Essex was given ‘a Root as usual’, prescribed ‘a gentle Purge of half Manna and half Syrup of Roses in thin Milk, once a Week for three Months’ and recommended to wash his eyes out with ‘cold Spring Water’ (Morley, 1766, p 21). Like all of the cures described in the case studies, Heatherly’s treatment was a composite remedy, not a specific.

Case studies like this are easily overlooked as commonplace components of eighteenth-century medical texts; they flaunt a practitioner’s successful treatments. But, in Morley’s pamphlet, the case studies also have other consequences, affecting how the genre and purpose of the Essay are perceived. At a first glance, they reaffirm the impression that, from the third edition onwards, the pamphlet is intended to function as a practical self-help guide rather than an advertisement: they provide readers with detailed examples of treatments and are assiduously corrected by Morley. For instance, between the ninth and tenth editions, Morley tweaks the description of a poor woman’s treatment by replacing warm water with a warm infusion of hemlock (Morley, 1773a, p 40; Morley, 1773b, p 43). He appears concerned to make sure that readers who are using the book to medicate themselves have the best advice.

But the case studies are not actually as carefully directed towards this purpose as they initially seem: how, after all, were readers to know which combination of ingredients they should use with the vervain root? Surely, if every case was different, none of the case studies could provide them with a ready-made answer? Ironically, this is underlined by the case of the poor woman which I have just used to show Morley’s concern with accurate advice. In that case study, which first appears in the ninth edition, Morley writes:

I referred her to follow what is laid down in John Newton’s Case No. XXVI in my Essay; only adding, that the poor Creature should steep her Leg in a warm Water for Half an Hour, and to keep it warm after steeping, least she should take Cold.

In this metatextual case study, which refers back to earlier editions of the pamphlet, Morley directs the woman to follow another patient’s treatment; he uses the pamphlet as a prescriptive aid. Crucially, though, he supplements the instructions in the Essay, emphasising that the pamphlet alone is not enough; his own expertise must be sought if an effective, truly tailored treatment is to be received. Accordingly, right up until the fifteenth edition, Morley continues to claim that it is better for patients to consult him in person than to receive written instructions remotely (Morley, 1776, p 84).

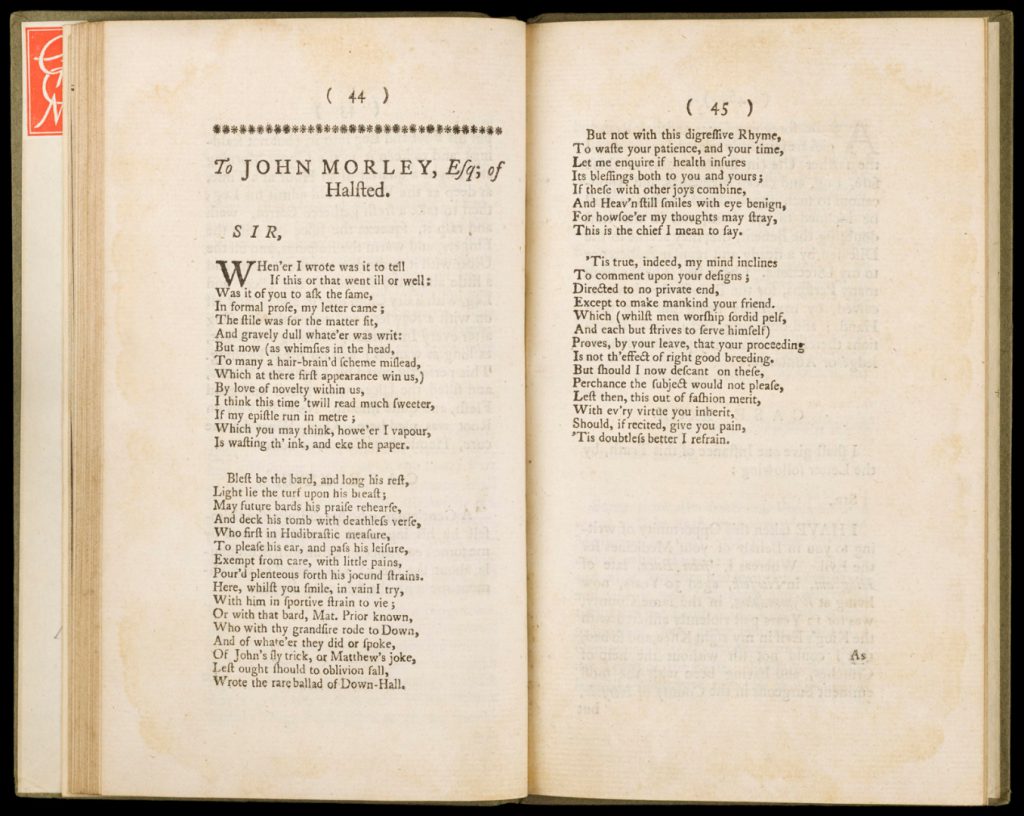

These middle versions of the pamphlet cannot, then, be unequivocally labelled as self-help guides. They seem designed to serve a range of purposes and readerships at once: as well as functioning as a self-help guide, the pamphlet continues to function as an advertisement for face-to-face consultations and as a prescriptive aid for Morley to draw on in his practice. All of these functions suggest a different role for the printed book in medical encounters. Indeed, examining the smaller changes that Morley makes between the third and tenth editions, one finds that they often suggest different audiences and purposes for the pamphlet. For example, by the sixth edition of the Essay (1770, pp 44–45), Morley has inserted a case study written in verse rather than the usual prose. This case study, attributed to an unnamed ‘Gentleman who […] distinguished himself by his ingenious Poems’, does not contain any of the usual information about symptoms and treatment (Morley, 1770, p 43). Instead, it is a playful panegyric which praises Morley’s charitable impulses. It also alludes to Morley’s notorious grandfather and his friendship with the satirical poet and diplomat, Matthew Prior. The poem therefore has the effect of portraying Morley as an affluent, well-connected and benevolent practitioner who mixes with other men of letters and leisure. It shows the pamphlet to be an important instrument of self-fashioning for Morley.

Something, however, clearly unsettled Morley about the poem: in the ninth edition, he removed the verse letter and replaced it with a plainer prose example which describes the symptoms and treatment of Aaron Wiskey, a shoemaker from Suffolk (Morley, 1773a, pp 37–39). This shift may have been reader-orientated: Wiskey’s case – containing information about symptoms and remedies – would have been far more useful to a reader looking to cure a case of scrofula than a glorifying panegyric. Furthermore, the shoemaker patient is closer to Morley’s alleged readership of craftsmen and labourers. The substitution shows that Morley’s continual reshaping of his pamphlet could be driven by two, sometimes conflicting, impulses: a desire to promote himself as a reputed gentleman intellectual and a desire to produce a ‘plain’, practical, patient-orientated pamphlet. In the later editions, this doubleness continues but, in his revisions, Morley becomes increasingly focused on readers and their changing needs.

The late editions, 1774–1776: readers as independent healers

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191210/005The final five editions published during Morley’s lifetime continue the trend of expansion characterising earlier versions: to each new edition, Morley adds a handful more case studies and testimonials so that the thickness of the pamphlet increases. This means that, whilst the eleventh edition (1774) contains 62 studies, the twelfth edition (1774) contains 65, the fourteenth edition (1775) contains 66 and the fifteenth edition (1776) contains 68.[18] These additions may have pleased Morley’s publisher, as they allowed him to market each edition on the title page as a ‘revised’ text, worth buying multiple times for the most up-to-date information. But the case studies were also a way for Morley to persuade readers that his medical services were acquiring increasing notoriety across the country: from the eleventh edition onwards, more of these cases and testimonials come from areas outside of Essex, such as London, Suffolk, Norfolk, Yorkshire, Berkshire and Cambridge. This geographical diversification is accompanied by rising statistics for the number of patients treated: in the third edition, Morley claims he has treated ‘above a thousand Subjects’ (Morley, 1766, p v), but by the fourteenth edition, this has risen to ‘several thousand subjects’ (Morley, 1775, p iii).

Morley’s pamphlet was apparently just as notorious as his person: in the twelfth edition, he claims that ‘about ten Thousand of these Essays, have appeared at Home, and Foreign Countries’ (Morley, 1774b, p 75). By the fourteenth edition, this number has risen to 12,000 (Morley, 1775, p 77) and in the fifteenth edition, the last edition Morley revised before his death, it has increased again to 14,000 (Morley, 1776, pp 83–84). Only pamphlets that were proven bestsellers and in high demand would have print runs exceeding 750 copies per edition (St. Clair, 2004, pp 256, 562). So, Morley’s statistics, if we take them at face value, suggest a large – and expanding – readership fuelling the production of his text. This suggestion is reaffirmed by the appearance of a pirated version of the fourth edition in Dublin in 1771.

The pamphlet’s growing and remote readership became increasingly important in later editions because Morley’s own mobility declined: the ninth edition of the Essay is the last time that Morley claims he is able to visit patients within a hundred-mile radius of London (Morley, 1773a, p 54). In the tenth edition, he states explicitly: ‘I make up no Medicines, nor will my almost worn out Eyes suffice to give any Directions in Writing’ (Morley, 1773b, p 57). By the eleventh edition, it is clear that there are now only two options left to Morley’s patients: to travel to him, or to heal themselves independently through the Essay (Morley, 1774a, p 82). The latter has, of course, been the proclaimed aim of the pamphlet since the third edition but it is only in later versions that Morley starts to model how the pamphlet might actually facilitate that independent healing: by the sixth edition, the Essay contains a case study including correspondence from John Buck, a man who has healed himself using ‘Mr. Morley’s Book’ (Morley, 1770, pp 46–47). Buck describes the treatments he has used on himself, but he does not describe how he extracted this knowledge from the Essay. In the ninth edition of the Essay, however, Morley rewrites the introduction to Buck’s case to provide a little more information: he claims that readers will be able to treat themselves remotely ‘by the Perusal of [his] Essay and a steady regular observation of the Rules as related in the preceding Cases’ (Morley, 1773a, p 41). In these lines, Morley acknowledges that readers will not instantly be able to turn his Essay into action; instead, they will need to ponder, ruminate and regularly study the collection of case studies, extrapolating a set of general rules by working out which symptoms merit which combination of ingredients.

In the tenth edition, Morley finally adds a case study which models how such reading might work in practice. This case describes how the Countess of Marchmont used the Essay independently to cure a poor man called James Smart:

He had a Vervain Root to wear at his Stomach, was ordered to take the Diet Drink prescribed in Mrs. Bulmer’s Case, Page 25, and the gentle Physic of Syrup of Roses and Manna, in Page 14, and to dress the Sore with Vervain Ointment, as in Winterflood’s Case.

The case study suggests that the Countess devised a new, composite cure from the cures described in previous editions; she matched the patient’s array of symptoms to those represented in diverse case studies. The Countess therefore takes on the role of a charitable practitioner, diagnosing and prescribing in the same way that Morley does in other case studies. One can see the appeal of such a process for readers: he or she could exercise agency within a reassuringly circumscribed sphere of options, putting together treatments from a set of possible ingredients already defined by Morley. Furthermore, the reader would have known exactly what was in the treatment. This would not necessarily have been the case with ready-made proprietary medicines or Latin prescriptions from qualified physicians.

From the eleventh edition onwards, more and more of the case studies Morley adds to the Essay are based on reader testimonials which depict this kind of independent medical practice. For example, in the eleventh edition, Morley adds a testimonial describing the cure of an eighteen-year-old man by another ‘charitable Lady, out of Berkshire’. This time Morley quotes correspondence from the Lady directly so we hear an increasingly active first-person readerly voice:

About two Months ago, we were advised to let him try your very excellent Remedies, published in your Treatise […] Not meeting a Case exactly similar, I ventured to collect something from different Cases, and used the following: First I put a large Vervain Root about his Neck, his Arm fomented, with Flannel, in a strong Infusion of Hemlock, Morning and Night; then Vervain Ointment to the Wounds, dry Lint, and a fine Rag, spread with the Ointment, all over, to prevent sticking. He took ten Grains of Jalap, and ten Grains of Cream of Tartar, once a week: The other six Days, a Dram of Antimony finely powdered, and washed down with Ground-ivy Tea.

Once again, we have an impressive act of synthesis, as the Lady devises a personalised treatment from the case studies which best represent the symptoms before her. The same autonomy is suggested by a testimonial added to the fourteenth edition, which describes how Edward Palmer, the governor of a workhouse, treated an inmate called William Bradley: after hearing of ‘Mr. Morley’s Book’, Palmer decided to ‘put [Bradley] under John Buck’s Case’ (Morley, 1775, p 76). Two more testimonials added to the fifteenth edition also suggest patient resourcefulness and independence: a letter from Mary Meakes describes how she used the Essay to heal herself over an extended period of two years and three months; the pamphlet was clearly not an ephemeral purchase or quick read for Meakes (Morley, 1776, pp 82–83). In another testimonial, Mrs E Hibberdine of Oxfordshire describes how she healed Mrs Anna Maria Palmer:

Sir, On reading your Essay, and recollecting what Dr. Lewis had said, of a cancerous Humour running withinside without any outward Appearance; I thought a scrophulous one might do the same […] The Vervain Root was then put on […] Then the Millepedes Pills, as in Case XVII, were given for her sore Throat […] Then she took the Antimony in fine powder, with Honey and Ground-ivy Tea, as in Case XLVII [..] she took the Diet Drink, as in Case XII, which quite removed that Complaint in a few Months.

In this case study, which is long and protracted, the successful treatment of scrofula is the result of a dialogue between reader judgement, Morley’s Essay, and the previous medical advice of Dr Lewis. In previous editions, Morley depicts orthodox medical practitioners referring cases to him that they cannot treat; practitioners communicate with practitioners (Morley, 1770, p 51). In this instance, however, it is the reader who brings together all of these different sources of expertise, synthesising them into a successful – and tailor-made – course of treatment.

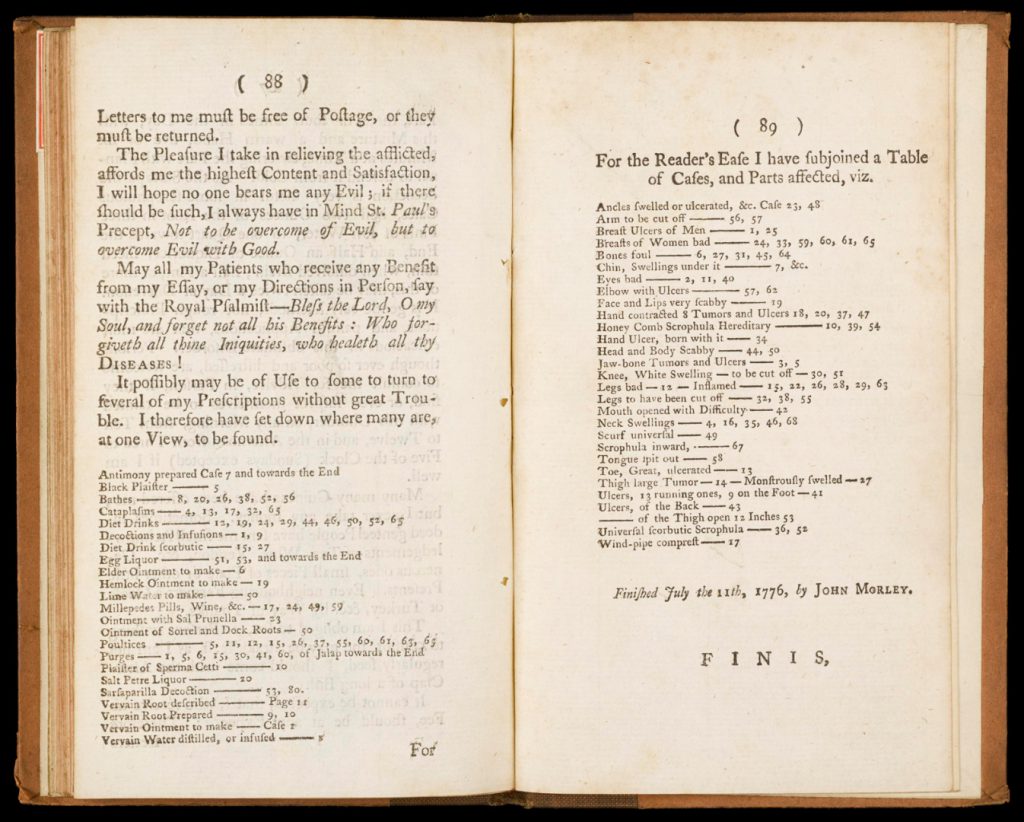

As well as recording readers using the Essay independently, Morley adds finding aids to the later editions which turn it into a better functioning tool for such independent use: in the eleventh edition, he adds an index which gives the page numbers of case studies associated with different body parts (Morley, 1774, pp 86–87). This index is appended to an earlier index (present from the ninth edition onwards) which lists case studies according to the various kinds of treatment deployed (plaster, diet drink, poultice, etc.). The body part index would have been much more useful than the treatment index to amateur, self-healing readers trying to match their unique collection of symptoms to those described in diverse cases. Along with the above reader testimonials, the index suggests that an increasingly infirm Morley was thinking more intently about how he might make the Essay into a self-healing aid capable of outliving him. There is a surprising resourcefulness here: whilst many pamphlets were ephemeral responses to particular controversies, events or (in the case of plague pamphlets) epidemics, Morley was trying to ensure that his pamphlet had a future beyond himself, even if he did claim right up until the fifteenth edition that it was better for patients to consult him in person than receive written instructions (Morley, 1776, p 84).

We have moved a long way, then, from the patients Morley imagines in his first edition: patients incapable of comprehending his remedy, who must have the ‘plainest and simplest Directions possible’ (Morley, 1760, p 30). This group has been supplemented by a more explicitly self-healing readership, capable of using Morley’s text independently and over long periods of time to treat complicated cases different from those described in the Essay. To be sure, these readers are not the labourers and craftsmen that Morley imagines purchasing his pamphlet in the introduction: a gender and class shift occurs and the readers depicted tend to be upper- and middle-class women who heal those less wealthy and less literate than themselves. It is this class of reader who would have had the time, leisure and domestic space to ‘peruse’ Morley’s text as he instructs and to imitate his own charitable healing practices. Nevertheless, the case studies added to the later editions of the Essay still demonstrate that a seemingly simple, easy-to-write and easy-to-read form could be pondered and ruminated by eighteenth-century readers; translating such texts into action could demand more time and thought than we assume. The annotations of those who owned and read the pamphlet (which are examined in the next section) testify to this.

The afterlife of the Essay

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191210/006Morley certainly succeeded in turning the later editions of his Essay into a self-healing guide that would outlive its author. Morley died in late 1776 or early 1777 and, in 1779, James Buckland was still certain enough of the pamphlet’s selling potential to fund a newspaper advertisement for the eighteenth edition.[19] After Buckland’s death in 1790, the right to print the pamphlet passed to his successor at 57 Paternoster Row, George Wilkie.[20] Wilkie printed the pamphlet until at least the 38th edition of 1818 and he may have done so right up until his death in 1823. The forty-second (and apparently final) edition was then published in 1824 by Sherwood, Jones and Co. and it continued to be advertised in their catalogue for at least 18 years at an increased price of 1 shilling and 6 pence (Catalogue of practical and useful books…, 1842, p 22). This increased price may have been caused by price inflation, greater tax duties on pamphlets, increased demand or diminishing supply.[21] However, the fact that Sherwood, Jones and Co. were still willing to fund the advertisement of the pamphlet suggests that it was a steady bestseller that was being actively reprinted; it was not just old stock being sold off. The thirty-first edition of 1797 was actually still being reprinted with a new introduction in New York in 1861. It seems that, despite great differences between eighteenth and nineteenth century medical practices – such as increased specialisation and institutionalisation – the pamphlet, its herb-based remedy, and pared back chemical inflections continued to attract substantial reader interest.[22] This practical, self-help emphasis clearly sold much better than the theoretical bent of Morley’s first and second editions.

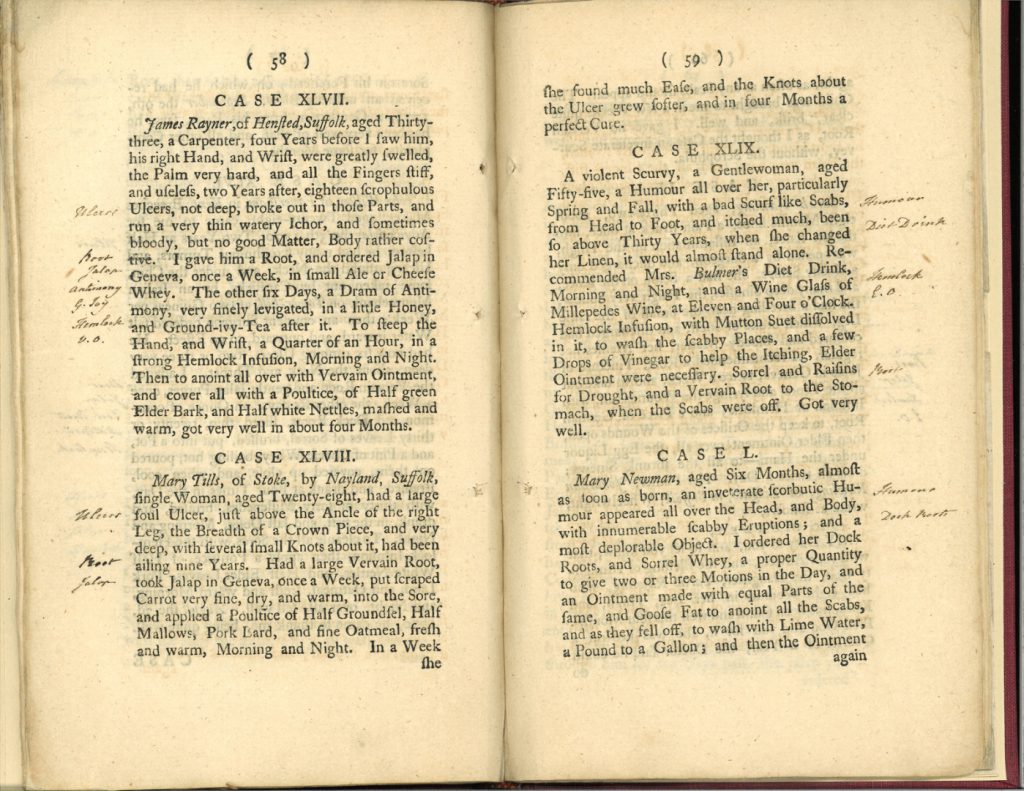

We must ask, though, whether many readers used the text in the synthesising, thoughtful way imagined in the later case studies or whether they engaged with it in different ways? The annotations on a copy of the twelfth edition (1774), now held at the National Library of Medicine in Maryland, suggest that some readers followed the examples Morley provided.[23] This copy contains annotations by several eighteenth or nineteenth-century hands: a hand writing in pencil has picked out key symptoms and key ingredients from the case studies, writing these in the margin. A smaller, seemingly separate hand has later written over these in ink, sometimes adding the names of other ingredients to the margins. This ink hand lists the core ingredients in each study in the first 55 case studies under the headings of particular symptoms. On page 58, for example, the reader has picked out the following ingredients under the heading ‘ulcers’: vervain root, jalap, antimony, ground ivy, hemlock, and vervain ointment. These are the ingredients that form the core components of Morley’s treatment and reappear from case to case. Other ingredients – such as ale, scraped carrot and pork lard – are not listed: this may be because they appear infrequently in cases and are specific to that patient’s treatment or because they are merely used to serve and apply the other components of the remedy.

What does this mode of annotating suggest?[24] Elaine Leong and Wendy Wall have argued that the way early modern readers annotated and organised household recipe books shows that they put a lot of thought, time and care into decoding, evaluating and enacting those texts. A similar amount of thought is implicit here: the way the reader lists the core components of each cure indicates that he or she was trying to summarise and compare the case studies, in order to understand the overarching rules governing Morley’s choice of medical treatment across the case studies. There is an attempt to extrapolate the general from the particular. The annotations consequently imply exactly the kind of ‘steady regular observation of the Rules as related in the preceding Cases’ that Morley advised his remote readers to undertake.

Translating these annotations into practice would not, however, have been an easy task. Sometimes cases involving similar symptoms require different treatments: in one instance, an ulcer on the ankle is treated by Morley with a vervain root, jalap, scraped carrot and a poultice of groundsel, mallow, pork lard and oatmeal (Morley, 1774, p 58). A few pages later, another ulcer on the ankle – which appears alongside a thick scurf on the rest of the body – is treated by a vervain root, a pint of cheese whey, water dock root, scurvy grass, hemlock leaves, flower of brimstone, elder ointment, hog’s lard and jalap (Morley, 1774, p 61). The reader, who simply annotates both case studies as ‘ulcer’, encourages comparison between these examples, but there is no indication how he or she (or future readers) would understand, reconcile, or choose between the different treatments listed. Additional medical experience would be required to decide which treatment is most appropriate. Translating the text into action therefore becomes a complex negotiation between written word, accumulated experience and tacit knowledge. It may not have been quite as easy a task as Morley’s model case studies suggest.

These annotations affirm that case studies deserve closer attention from historians of medicine: as well as operating as formulaic advertisements for practitioners, they could operate as important cognitive tools for readers. We must remember, though, that not all readers would have been willing or able to spare the time this ‘steady’ reading process required. For example, in a copy of the seventh edition owned by the Science Museum, a reader has not annotated any of the case studies; he or she has only underlined Morley’s description of the vervain root. This suggests that the reader was predominantly interested in Morley’s cure as a specific or quick fix and not as a more extended, patient-specific mode of treatment involving multiple components. The type of cure offered in the Essay therefore shifts according to reader interpretation. Some readers actually rewrote Morley’s cure entirely: in the copy of the twelfth edition described above, a reader – possibly the same reader responsible for annotating the case studies but writing in a more cursive, less formal hand – has copied a different cure for scrofula, allegedly used upon a farmer’s wife (Morley, 1774, p iii).[25] The cure contains some of the recurring, peripheral ingredients in Morley’s case studies (elder ointment, sorrel and lint), but these are combined with meadowsweet, not vervain. This individual found or developed his or her own cure and judged it to be just as – or more – efficacious than Morley’s remedy. For this reader, the Essay became a repository for new healing knowledge.

Conclusion

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191210/007The reading of a book is no less skilful, and no less local, than the conducting of an experiment […] we need to create a history of the reading practices surrounding scientific books as detailed and intricate as the appreciation we already have of the experimental practices surrounding scientific instruments.

This article demonstrates that even short, repetitive forms of medical writing could invite a variety of ‘local’ and ‘skilful’ reader responses. Formulaic features such as case studies did not translate into homogeneous modes of reading and information could not instantly be translated into practice: it had to be sorted, sifted, compared and generalised. It also needed to be assimilated or combined with what was already known. Theorists of tacit knowledge have long recognised that such a negotiation is necessary in translating any kind of written instruction into action.[26] However, such insights have not often been applied to pamphlets. If we consider them merely as ephemeral texts or ‘quick reads’, we overlook the range of ways in which they could convey information and the variety of timescales over which that process could occur; as we have seen, some readers consulted Morley’s pamphlet for years. Consequently, we must heed William St. Clair’s warning that, ‘the periodicity of reading, with its changing patterns of stacked chronological layers, is so different from the periodicity of writing that it cannot be adequately captured by traditional linear narrative’ (St. Clair, 2004, p 435). This is especially applicable to the thriving second-hand book market of the eighteenth century in which different readers would have consulted earlier and later editions of the Essay simultaneously (Fissell, 2007, p 112). The ways in which they engaged with those editions would not always have mapped neatly onto Morley’s evolving ideas about the pamphlet’s function.

This study has shown, however, that Morley’s aims were not always as transparent as they seem; furthermore, like reader trajectories, they are not always explainable through straightforward chronologies and teleological narratives. This is because Morley was continually experimenting with different modes of self-presentation and imagining different functions for the pamphlet. Often, he was happy for these to co-exist, layering new material on top of old material as he extended the length of the Essay: by the fifteenth edition, the pamphlet could function simultaneously as an advertisement for Morley’s medical services, as a ready-made prescription for him to supplement in person or in writing, and as a self-help guide that provided readers with a quick-fix specific remedy and a more labour-intensive way of determining a composite, tailor-made treatment. Individually, many of these functions are not extraordinary or surprising, but the way in which they are layered and juxtaposed again compels us to reassess our assumptions about pamphlets and other kinds of medical ephemera: these were not always intended by writers to mediate the relationship between patients and practitioners in static and simplistic ways. On the contrary, the cheap and changeable nature of their form made them the ideal shapeshifters through which that relationship could be continually remodified. It is only by paying more attention to such productions – and their numerous textual and material forms – that we can begin to appreciate the full range of roles they played in eighteenth-century medical encounters.

Acknowledgements

The research for this article was supported by the Wellcome Trust [grant no. 213159/Z/18/Z]. I am indebted to the Wellcome Trust for the secondment fellowship grant and to the Science Museum for acting as a host institution. I am particularly grateful to the team at the Science Museum Library and Archives (both in Wroughton and London) for helping me to navigate the Museum’s collections. Prabha Shah, Nick Wyatt, Silvia de Vecchi, Venita Bryant, Elizabeth Waeland, John Underwood and Doug Stimson all made me feel very welcome and provided me with invaluable advice as I explored the collection.

Tags

Footnotes

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

James Buckland’s will stipulated that Thomas Longman (1731–1794), another bookseller on Paternoster Row, should advise on the dispersal of stock; he must have passed the Essay on to George Wilkie. See Buckland’s will at the National Archives: PROB 11/1188/227.

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text