Textiles in a modern age

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221817

A photographic essay

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221817/001Introduction

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221817/002Raising sheep and making things from wool was Britain’s first great industry, which makes the choice of the woollen textiles sector as the initial focus of the Congruence Engine research a particularly appropriate one. Textiles have been a recurring theme in my work as a photographer. When I began to explore the stories of Britain’s migrant communities in the 1980s, I found that it was the textile industry that had drawn people to Yorkshire from places as far apart as Europe, the Caribbean and the Asian Subcontinent. I have also become fascinated by how the innovative spirit of textiles that once powered the North is fuelling a hi-tech future.

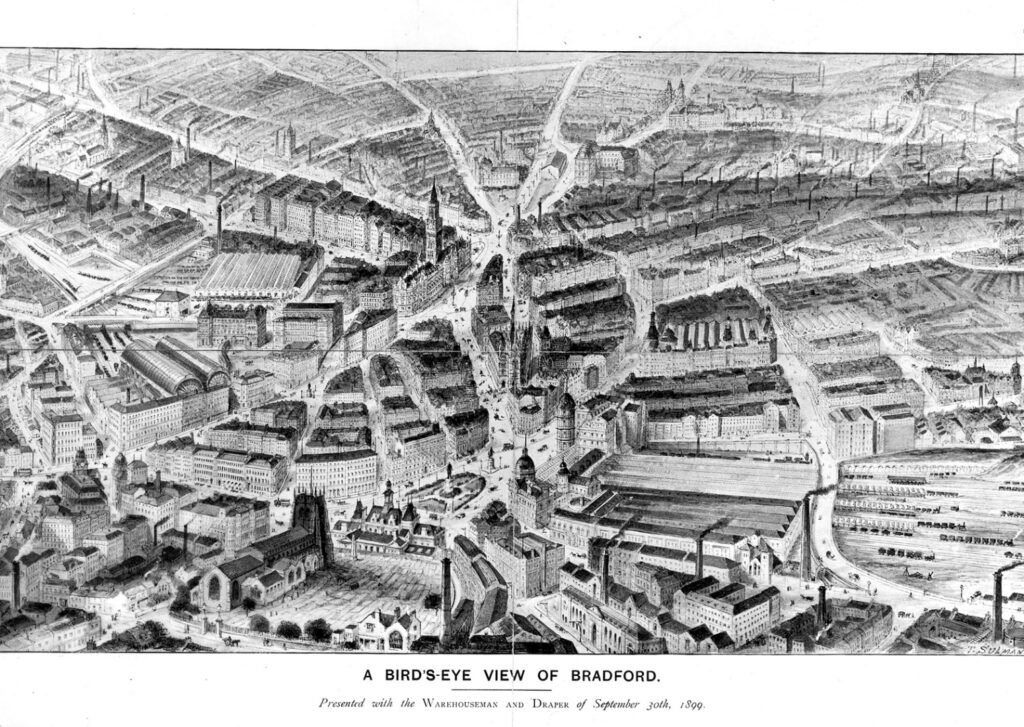

The Congruence Engine’s opening investigations were based in and around Bradford in West Yorkshire, which was also a fitting choice as, in its heyday, the city was once the woollen textiles capital of the world.

Using Bradford and the surrounding region as a case study this photo essay raises questions about how we might define and/or categorise the term ‘textile industry’ and the collections deemed relevant to it. The images explore how this may evolve as the textile industry itself undergoes radical change.

Bradford became pre-eminent in the woollen textiles world because it was, to borrow a term, a congruence engine of the Industrial Revolution. Its early development and rapid rise were based on the local abundance of water, wool, coal, stone and iron, and Bradfordians made enterprising use of this favourable confluence of geography and geology to outgrow their rivals.

A brief history

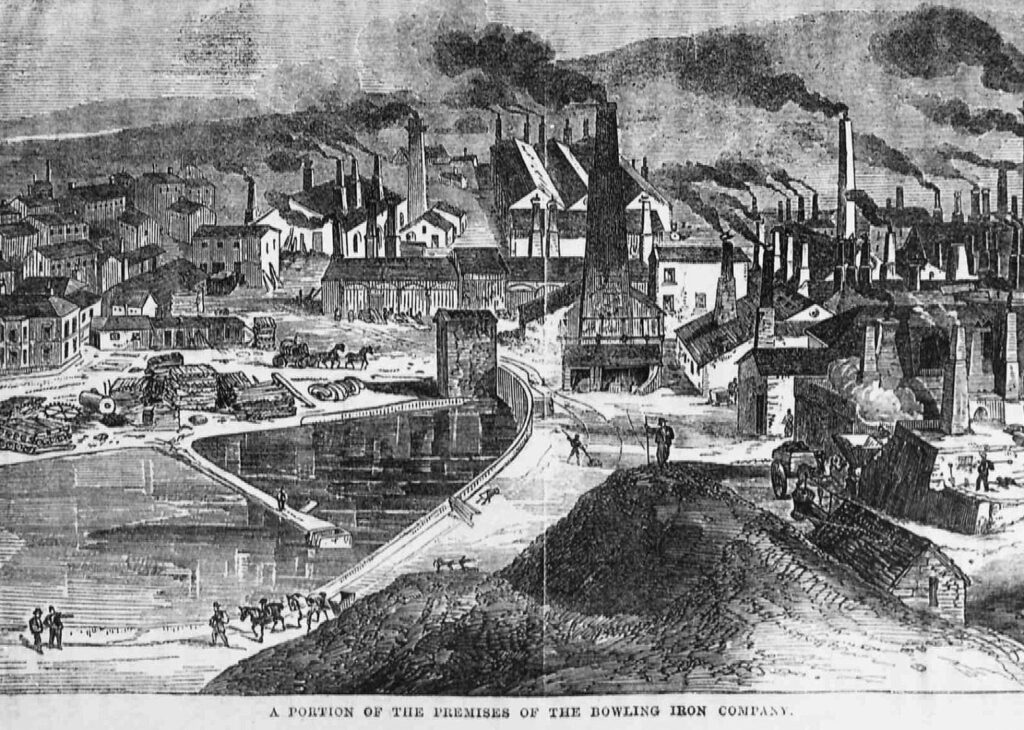

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221817/003Bradford opened its first textile mill in 1799, and the arrival of power looms a few years later set Bradford on its way to becoming the worsted capital of the world. Bradford companies such as Bowling Iron Company and Low Moor Iron Works boomed in the nineteenth century. In 1867 the latter alone employed about 4,000 people, with each company exporting their products all over the world. They also provided a ready source of the metals needed to engineer textile machinery to fill the factories of what became, by 1850, the fastest growing town in the UK.

However, such growth came at a cost. In 1876 historian William Cudworth wrote ‘The appearance created by the (Low Moor) works themselves and their surroundings had been not inaptly likened to that in the vicinity of the crater of some volcano’. The Bradford Canal, which linked the city centre to the Leeds to Liverpool canal in Shipley, was built to transport raw materials in and finished products out but was so polluted it sometimes caught fire. Overcrowded slums that housed much of the rapidly growing population existed alongside some of the most lavish civic and industrial architecture in the country.

Whilst the textile industry provided the skeleton of this industrial behemoth a host of related industries grew up to both feed it and provide the connective tissue that enabled it to function and interact with the outside world. During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries Bradford’s tentacles of trade spanned the globe. Canals, roads and railways supplied raw materials, which included not only Australian wool but the Peruvian alpaca hair and Indian silk from which Salts Mill and Lister Mills made their respective fortunes. Finished goods moved in the opposite direction as a busy printing industry produced literature in dozens of languages to market Bradford products globally. Services such as banking and communications flourished. The chemical industry supplied, among many others, Ripley’s Bowling Dyeworks, the largest textile dyeworks in the world. Engineering firms, many of them based in the nearby town of Keighley, made textile machinery for local mills and went on to supply the industry worldwide. So industrious were local people that they even made soap and lipstick from the effluent processed at Esholt’s sewage works, which was thick with lanolin flushed out by mills washing wool.

When textiles dominated Bradford, the city was so steeped in the culture of wool that it permeated every aspect of local people’s lives. For many, the mill not only controlled your working day, but it also owned your house, it determined your health, it organised your leisure time, it decided who your friends were and to whom you got married. Sometimes it even told you what to think, where to worship and how to vote. It also employed a cosmopolitan labour force drawn from across the world.

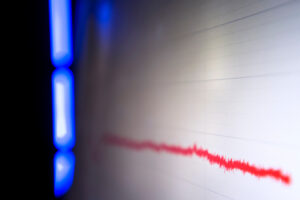

The textiles industry was so ubiquitous in Bradford, as it was in so many other British towns and cities, that it is all but impossible to neatly delineate it, which also raises questions about how to contain it within a single ‘textiles industry collection’. One approach is to use oral history. The collections of the Bradford Heritage Recording Unit, held at Bradford Industrial Museum, include hundreds of life story interviews with people who worked in textiles and associated industries, or migrated to the area because of the employment opportunities offered to them and/or their families.[1] Made mainly during the 1980s and 1990s, much of what was said in these audio recordings, such as personal memories of bullying, sexual harassment and racism, had never been made part of an industrial collection before. Sometimes people’s feelings, emotions, attitudes, reflections and relationships are more eloquently spoken than written down. This oral history collection presents its own challenges in terms of cataloguing and access, but it does offer fascinating insights into the multifaceted impact of textiles on everyday life, the complex network of relationships between people, places and things, and how porous all of these elements are.

Over the past fifty years Bradford has fallen rapidly from its position of world dominance to a point where the local textiles industry is scarcely visible. However, that doesn’t make it any easier to delineate it. Close examination reveals that textiles continue to pervade our lives and have the capacity to transform our world in ways that were unimaginable just a few decades ago.

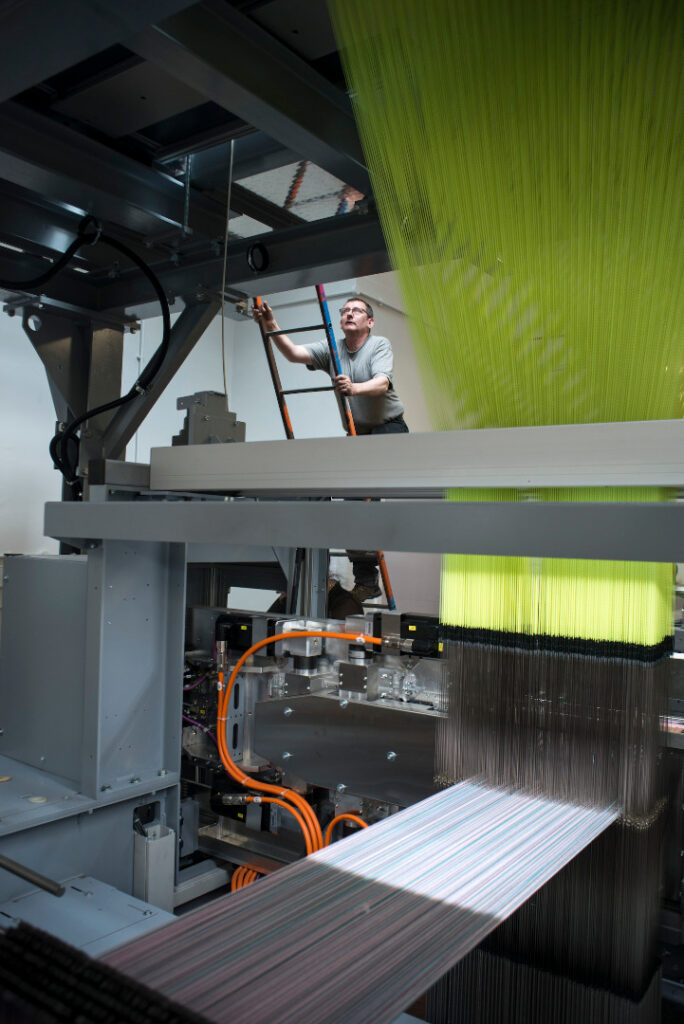

It is easy to see how centuries of textile production have shaped rural and urban landscapes across Britain, but the industry has also left an intangible legacy of experience and expertise focused on working with fibres that is perhaps less obvious. Modern-day textile production goes well beyond clothes and furnishings, as new technical developments are redefining textiles as a uniquely multidisciplinary field of innovation and enquiry.

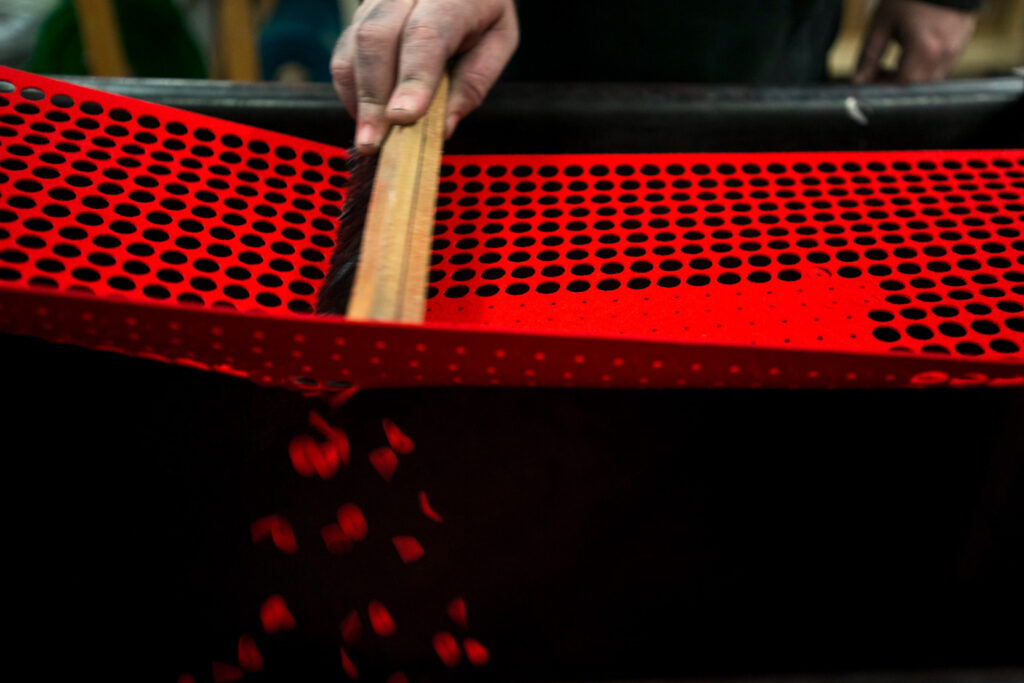

Today, Bradford, and the wider regions of Yorkshire and Lancashire, no longer churn out ‘run of the mill’ products in vast quantities, but the sale of exclusive products to niche markets has maintained the role of textiles as a vital part of the region’s economy. People working in modern industries continue to use wool, cotton and an array of other raw materials, together with their imaginations, to adapt traditional methods and machinery and make distinctive goods for global customers. The mills that survive are highly specialised, supplying short runs of high value to the technical fabric markets or the world’s premier fashion houses. Rather than stocking high street shops, Yorkshire cloth is worn by NASA astronauts, families such as the Obamas and the British Royals, and dresses a vast range of on-screen characters, from James Bond to the Pirates of the Caribbean.

Textiles also provide a unique skill and knowledge base for cutting-edge research, as traditional technologies are used in new and surprising ways to develop a huge variety of pioneering materials. Textile research programmes are led by businesses but also universities, such as those in Bradford, Leeds and Huddersfield which were originally established as nineteenth-century centres of excellence for textile education.

The industries benefitting from these skills range from civil engineering (where woven scaffolding is in use within buildings and bridges), solar power generation (nanoelectronic devices are being incorporated within the fibres of a yarn), medicine (in the bio-textiles used for making replacement body parts) and the automotive and aerospace industries (where weaving technologies create incredibly strong, lightweight materials for building vehicles – from bikes and cars to aeroplanes and space satellites).

Thus, the innovative spirit that enabled the textile industry to power the world’s first industrial revolution seems alive, well and driving a new revolution: reinventing textile technologies for the twenty-first century. The Congruence Engine’s investigations in Bradford show that for over 200 years textiles manufacturing has been at the core of an industrial ecosystem that has proved difficult to unravel, but that continues to evolve and adapt.

The recent photographs I have included in the main body of this essay show that the task is not going to get any easier, with ongoing research and development demonstrating the ground-breaking potentials of textile products. As biomedical textiles – including silk-based blood vessels, heart valves, tendons and ligaments – commonly become part of the very fibre of the inner human body, and the aerospace industry uses woven fabrics to build vehicles to explore outer space, we will have to consider how to define what we mean by ‘textile industry’, and to think about how to organise the datasets that document our textile industry collections.

Congruence Engine is supported by AHRC grant AH/W003244/1.

Article keywords

Textiles, Bradford, Photography, Industrial History, Social History, Oral History, Innovation, Weaving, Biomedical textiles, Museum Collections, Museum Catalogues

Appendix A: images

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221817/024

All of the above images were taken by Tim Smith. The images were used in Weaving the Future, an exhibition of film, photography and artefacts commissioned as the flagship arts event of the 2019 annual Saltaire Festival.[2]