Rather unspectacular: design choices in National Health Service glasses

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/170703

Abstract

This article considers the design and production of spectacles in Britain following the introduction of standardised frame styles under the National Health Service. NHS spectacles were provided as a functional, durable medical appliance to be delivered cost-effectively and there was no explicit concern for fashion or the patient experience. The actions of the government and professional bodies greatly affected the trade in eyewear and thus restricted opportunities for innovative design and consumer choice. Within the range of state regulation frames there was no active concern for ‘design’ in terms of appearance and it was only through the purchase of private frames that significant choice and variety in eyewear could be attained. The scope for the public to select a more fashionable frame whilst receiving an element of state aid was through the purchase of NHS hybrid private frames.

Keywords

design, eyewear, government intervention in design, medical humanities, National Health Service, NHS, NHS glasses, optical trade, social stigma, utility, welfare state

Introduction

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/Spectacles, or eyeglasses, are designed objects which bring a huge proportion of the UK population into an encounter with a scientific appliance.[1] These objects are pieces of precision engineering used by their wearers on a daily basis, and they are complex scientific instruments with a medical purpose: to enable visual clarity and optical functionality. The history of design and manufacture of eyewear is inextricably linked to scientific developments in optics and frame materials, the medical and optical professions, and furthermore associated with wider changes in society. Spectacle frames are an everyday item of scientific design that traverses technological and scientific histories along with medical, social and cultural histories. In the context of post-Second World War Britain and the beginnings of the Welfare State this story also engages with political, business and trade histories. Kjetil Fallan argues that examining everyday things is essential to understanding society and culture and that ‘Design History today is no longer primarily a history of objects and their designers, but it is becoming more a history of the translations, transcriptions, transactions, transpositions and transformations that constitute the relationship among things, people and ideas’.[2]

This article originated from design historical research undertaken on the course run jointly by the South Kensington institutions the Royal College of Art and the Victoria and Albert Museum.[3] The primary sources used are museum objects, government archive documents, and professional and journalistic literature; these are used to uncover the background to the topic and explain developments.

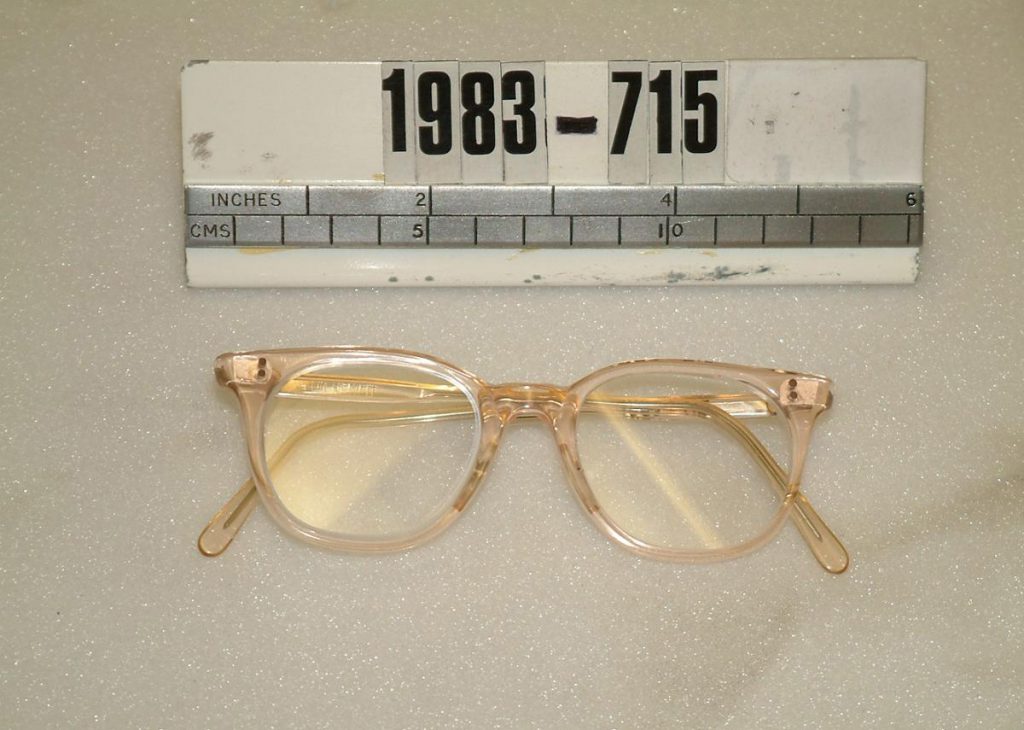

The Science Museum collection contains optical instruments that demonstrate the technical and scientific developments in optics, eyewear and glasses, and contains several examples of National Health Service spectacle frames.[4] The spectacles are categorised along with the optics and ophthalmology collections; a significant number of these were acquired from the Wellcome Collection and are associated with medical items such as sight-testing equipment and surgical instruments. However, the Dixey and Dunscombe collections also include a range of fashionable eyewear in addition to the NHS examples.[5] This article examines the key factors that affected the design, production and appearance of these spectacle frames, which were worn by a large section of society in post-war Britain. The history of the range of spectacles produced for NHS provision between 1946 and 1986 is not only connected to the optical profession but to political issues surrounding provision of welfare and state aid, and to medical discourses. The period under analysis here sees the rise of patient participation in healthcare provision, and Alex Mold has identified that the notion of the patient as a consumer becomes explicit in policy during the 1970s (Mold, 2010). To provide a comprehensive design historical treatment this historical discussion would extend beyond analysis of the production concerns, design and appearance of the items to consider the consumption and mediation of the objects; however, as shall become clear these items were not sold in a standard retail context and uncovering the consumer experience is complex. Spectacles are personal objects that are primarily a medical aid. Many people wear corrective frames through necessity rather than fashion choice, and hence can have an antagonistic connection to these objects. However, it is interesting to note that certain styles and category of eyewear, especially sunglasses, are also fashion accessories and fashion theory can be useful here. Scholarship by fashion historians Lurie, Davis and Barnard suggests that garments and accessories can be imbued with power to communicate and have a power to reveal and mediate notions of gender, sexuality and social class.[6] In addition to the practical role of enabling vision, spectacles affect the wearer’s external appearance, have the power to transform or disguise, can contribute to a sense of identity, and are also used in communicating a variety of messages about character. Examination of visual and popular culture references are useful to uncover the relationship that people have with objects as well as other people’s perceptions; however, due to the scarcity of resources regarding consumption of eyewear and patient experience, predominantly due to a ban on advertising in this industry during the time period considered, this is a problematic area of enquiry. The discussion presented here is located firmly in the evidence available: consequently, this predominantly reveals the voices of the optical profession and the government; and, there is still much potential for exciting research to uncover the stories of the patients and consumers of these items and their relationship to these vision aids.[7]

Context

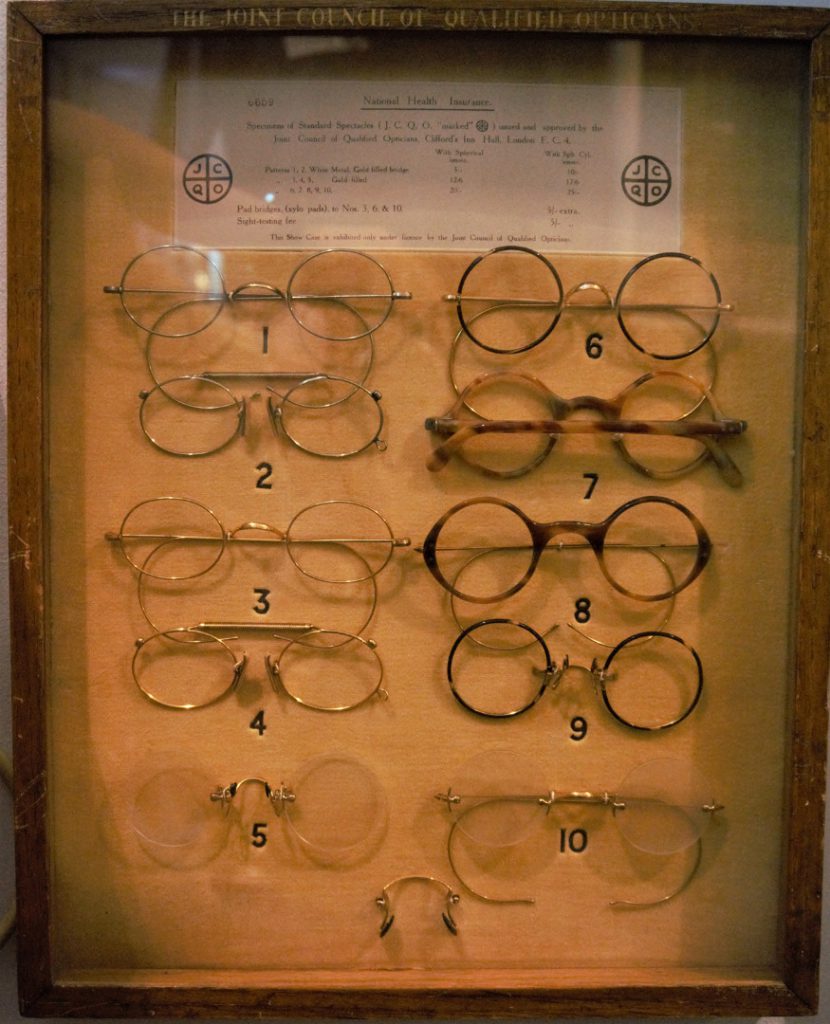

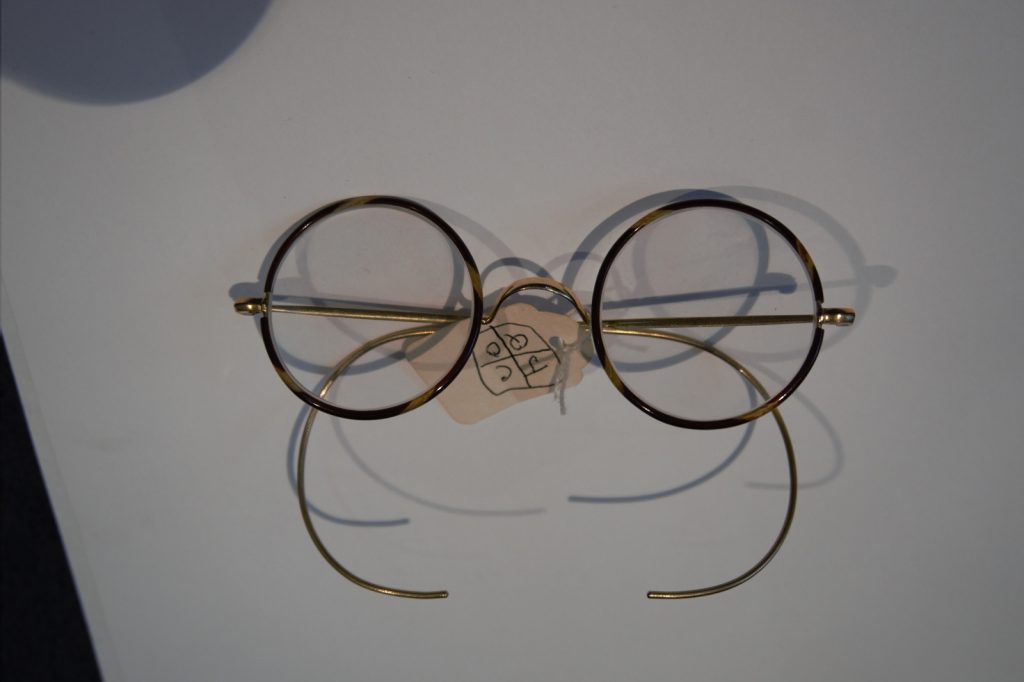

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/170703/002Twentieth-century social history in Britain is largely shaped by the philosophy demonstrated in the social project of the Welfare State. Prior to this nationalised system early twentieth-century healthcare provision was through private funding, charitable trusts, and health insurance schemes. Medical and optical services were offered on a localised basis, availability varied according to geographical location, and the level of service was linked to the financial status of the patients. The National Health Insurance Act of 1911 had established an insurance scheme that allowed those in employment to make financial contributions towards health care and provision in case of unemployment.[8] This scheme covered the fees for a panel doctor, maternity, convalescence or sick pay. Ophthalmic aid was not included until 1923, when the Approved Societies who administered the Act had a substantial cash surplus and funded eye examinations and offered a grant for corrective eyewear.[9] This grant would cover a free pair of ‘utility’ spectacles, but with an option to pay the difference for a more expensive frame. This extension of the National Health Insurance scheme in 1923 to cover optical benefit provided the optical world with a problem. As there was no statutory recognition of optical qualifications or register of opticians it was unclear who could or should provide benefits. A new body was established from three optical associations: the British Optical Association (BOA), the Spectacle Makers Company (SMC), and the Institute of Ophthalmic Opticians (IOO); they joined together to form the Joint Council of Qualified Opticians (JCQO). The BOA and the SMC were examining bodies that offered diplomas, whereas the IOO had a strong branch system throughout Britain and close links with the refraction hospitals (eye hospitals) (Smith, 1996, pp 11–15). Between them these organisations represented a large proportion of the optical practitioners. The JCQO brought together all qualified ophthalmic opticians, created an ethical code, and formed the first register of practitioners. The JCQO also selected and approved the range of ‘utility’ spectacle frames available under the National Insurance scheme (see Figures 4 and 5). Despite measures taken by the JCQO regarding representation and qualification, there were expressions of discontent and the problem of registration of opticians remained an issue of concern to the profession.[10]

For those patients who did not contribute to an insurance scheme there were other outlets to obtain optical appliances. Spectacles could be bought at chemists, through untrained retail opticians (who were not optometrists), and from certain department stores and mail-order catalogues.[11] During the Second World War the optical profession worked to provide vision aids for servicemen and spectacles for wear with gasmasks, and although NHI frames were described as ‘utility’, government records do not show any explicit links in the optical profession to the strategies of the British Utility Design Scheme introduced by the Board of Trade as part of wartime austerity measures.

The government and design

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/170703/003Economic and design historians have observed that the wartime context increased government powers and that the main outcome of these circumstances was to replace the trade and market forces with a ‘centrally managed economy in which the state allocated the most important resources, decided what should be produced, and determined how much should be paid for it’ (Howlett, 1994).

Cheryl Buckley and Judith Attfield both argue that this had enormous repercussions for design because central government took control; for example, with the introduction of rationing in 1941 and in 1942 the British Utility Design schemes; and they managed consumer demand on the basis of need rather than desire in an essential strategy to allow fair distribution of goods in times of hardship (Buckley, 2007). In the post-war period of austerity a fairly rapid recovery was achieved by continuing the state-managed economy, and this was paralleled by increasing state intervention in design. From 1930 to 1951 several government initiatives brought a focus on improving design, raised the question of what was good taste, and sought to educate the public about quality standards with a view to supporting the domestic economy in the context of anxiety about foreign competition. A board of trade committee, chaired by Lord Gorell, had examined how best to promote design for industry; this 1932 report resulted in the establishment of the Council for Art and Industry in 1933 and its successor the Council of Industrial Design in 1944. The government agenda here was to educate and inform in order to stimulate trade in both the domestic and export markets; exhibitions, fairs and publications were produced such as Britain Can Make It (1946), regional exhibitions such as Enterprise Scotland (1947) and ultimately the Festival of Britain (1951). Whilst these exhibitions have been the subject of much discussion and debate among historians about their aims and efficacy, their existence demonstrates that the government recognised the value of design awareness to the production of goods and trade in the economic regeneration of Britain.[12]

The circumstances for the government’s role in the optical trade were somewhat different; there was no need to generate demand for products through promotion of good design choices because the new universal National Health Service, with its provision for optical care, created the market and huge demand. There is no direct evidence of a link between the advisors of the Council of Industrial Design, or an active design-led agenda, with the initial production of the NHS range of spectacles; the government’s concern was that the frames could be manufactured, lenses ground, and spectacles distributed to meet the huge demand that was created at the inception of the service. As we shall see, this was a unique set of circumstances for society, the scientific and medical professions, and the optical trade.

Optical industry context and histories

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/170703/004This article does not discuss the complex workings of the ophthalmic profession and its organisations in detail; here it offers merely a brief background to give sufficient context for this topic. Vision aids date back to the thirteenth century and optometry has a complex history, involving centuries of scientific and technological advances and, more recently, the complicated politics of several professional organisations; some excellent histories of the major associations can elaborate the finer details of these relationships (Law, 1978; Mitchel, 1982; Stanton, 1963).[13] As can be seen in the Science Museum galleries, the nineteenth century saw huge advances in mathematics, physics and associated optical sciences; developments in materials resulted in improvements in lens production and the ability to manufacture optical appliances such as spectacles, telescopes, microscopes and other optical instruments. Opticians sought official recognition of their skills through a request for official training and qualifications. The Optician journal was founded in 1890 as a forum for discussing issues relating to optics and professional recognition.[14] As a historical resource this publication offers a wealth of information revealing the concerns of the trade and provides a fruitful primary source for this industry; and the Optician weekly journal continues to be produced today, with a readership of optical practitioners and trades. Within the world of eye care there are variations in the responsibility and qualifications of different optical practitioners; an ophthalmologist, an ophthalmic optician; and a dispensing optician.[15] For the purposes of clarity this article uses the term ‘optical practitioners’ when referring to eye specialists that the public may encounter, the term ‘optical trade’ when referring to manufacturers of frames and lenses and prescription houses, and ‘optical industry’ when referring to both sides of the profession.

The National Health Service Acts of 1946 introduced a health service that was accessible to all citizens providing free medical care, dental treatment, sight tests and ophthalmic services.[16] Radical plans were made for special ophthalmic departments and clinics to be part of hospital eye services. These plans were ambitious and until they could be developed a Supplementary Ophthalmic Service was organised, administered by the NHS executive committee of each local area.[17] Initially a sight test and corrective optical appliances were free, but charges were gradually introduced for the NHS range of glasses. The overwhelming demand for eyecare and corrective aids caused the first challenge to the principle that healthcare under the new ‘Welfare State’ was free at the point of delivery. Hugh Gaitskell introduced charges for dentures and spectacles and this caused a crisis in the government in April 1951 when Nye Bevan, Harold Wilson (then President of the Board of Trade) and John Freeman resigned in protest at the breach of the main principle of the fledgling NHS.

The NHS range of spectacles

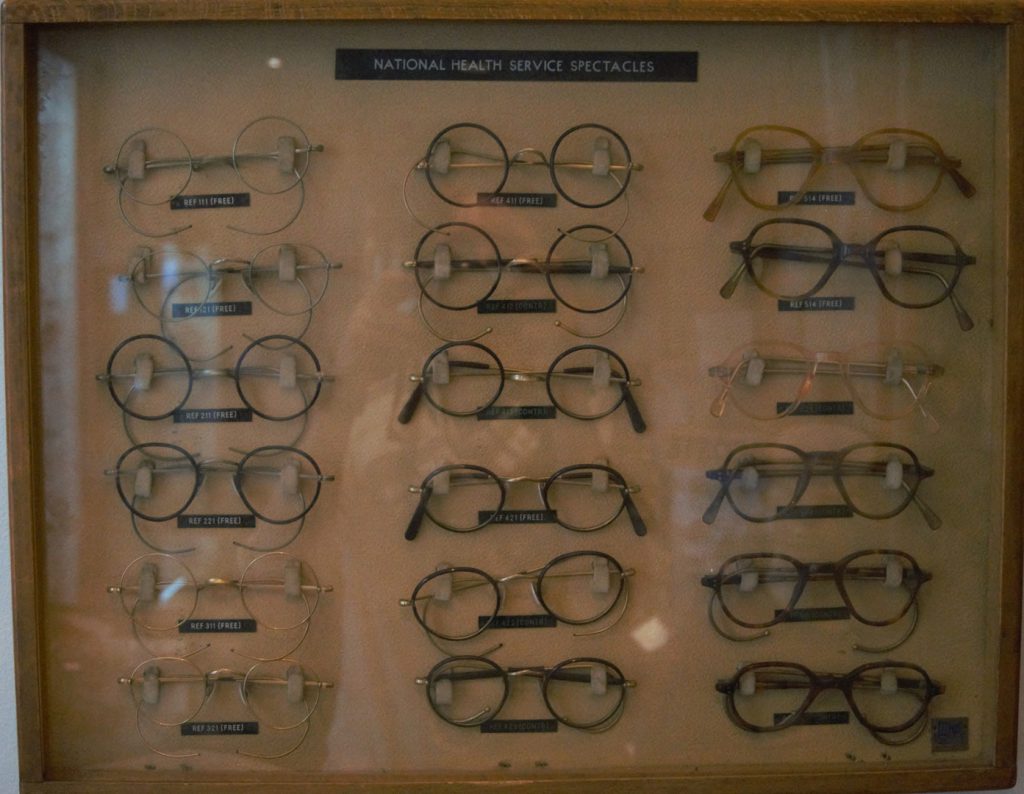

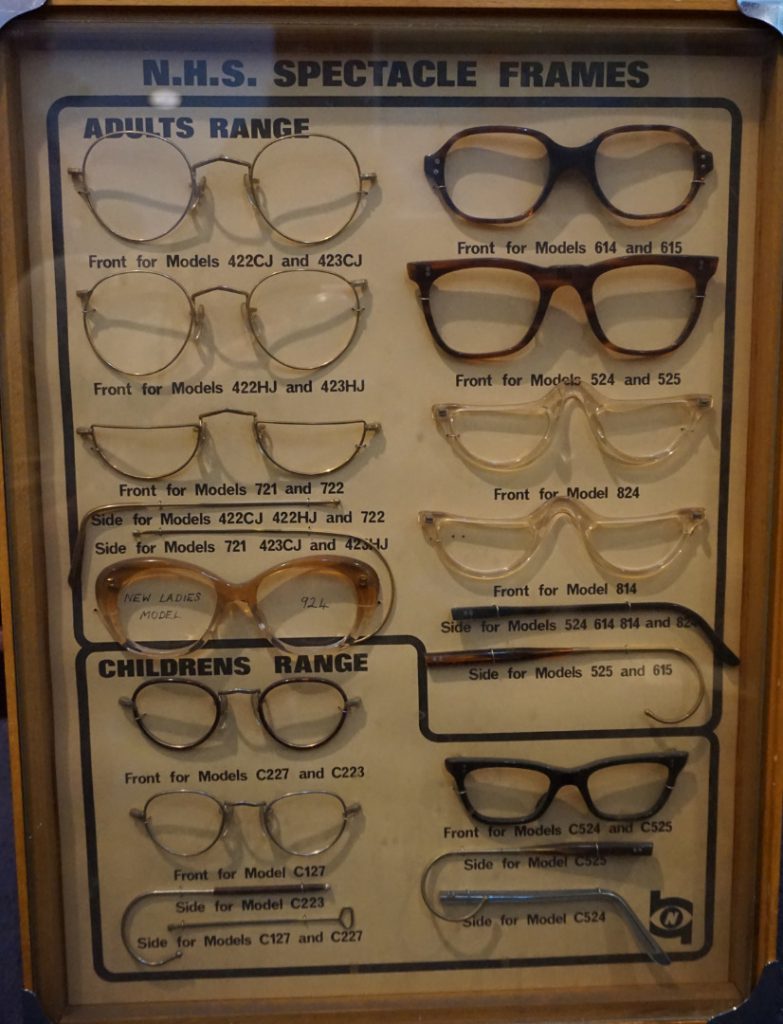

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/170703/005The range of spectacles provided by the NHS supplementary ophthalmic services was based on the existing NHI utility frames.[18] The frames available under both schemes were intended to fulfil a basic practical function: to hold lenses. The frames needed to be simple and cheap to produce, easy to glaze, and durable for the patient; the provision of styled frames and choice to the patient were not considerations. The government’s criteria for the range was that there should be a spectacle frame suitable for every medical requirement; frames were available for children and adults, and other frames were provided for special medical conditions. In a pair of simple spectacle frames there are many variable measurements: the width of the face; the distance between the pupils (PD-inter-pupillary distance); the bridge over the nose (DBL-distance between lenses); and the measurement of the side arms which rest on the ears and secure the frame to the face. For utility frames a degree of standardisation was therefore needed in order to enable large-scale production, and manufacturers produced a selection of sizes.[19]

At the inception of the health service the Ministry of Health formed a liaison committee to seek advice from the industry concerning the production capacity nationwide.[20] The range of frames was considered in terms of function and economy. Government notes stated their selection criteria:

…The types in the free range must however cover everything clinically necessary for any type of applicant and must be of good quality but not luxurious standard of appearance. The Minister’s aim is to concentrate on the minimum number of types in the free range in the hope of getting better prices for mass production.[21]

Although choice and styling were of importance to the patients these were not thought appropriate for the health service. Minutes from a meeting in May 1948 stated that ‘from a health point of view, any type of frame which would hold the lenses in position would be adequate. Other considerations were not valid in considering a health service’.[22]

Frames were available in three materials: nickel, gold-filled and cellulose acetate (plastic). The range of NHS frames was divided into groups, known as classes: one class of four frames were free; other classes of frame required a financial contribution as they were more expensive to produce. Metal frames were similar to those from the NHI glasses range; some of the metal frames were available with coloured plastic-covered rims. Plastic frames were available in a selection of colours. In 1948 there were 33 frames in the National Health Service range.

Although these figures suggest an element of choice, the frames were in effect only variations on a limited range of simple eye shapes with differences in the bridge, the position of the joints and the type of sides.[23] There were slight differences between frames, their materials or colour, and the combination of the design components that enabled the government to claim that there were such a large number of spectacle designs available. The frame styles, or patterns, under the NHS were given a reference number. The three-digit number referred to a specific frame shape and a particular material. If, for example, the pattern was intended for a child the code would be prefixed with the letter ‘C’, or if the style had ‘high joints’, where the arms were fixed to the front rim, the code would include the initials ‘H.J.’. Metal frames in the popular Windsor style, similar to those available under the NHI scheme, were produced in nickel and given the code 211 or 221 dependent on the style of bridge. There were four more style numbers for the children’s size of this frame type.[24] Other variations of the style produced in gold-filled metal required a financial contribution but produced nine more style numbers. There were also slight variations on the plastic frames with differences in the bridge – either ‘regular’, ‘pad’ or ‘keyhole’ – and the position of the joints, either centrally or high on the top of the frame.

When the service was introduced in 1948 frames from the old National Health Insurance range were used up then NHS patterns were produced. The information available for the design of NHS frames was very limited and provided only through comparison to the patterns previously available on the NHI schedule and by the simple description of frames in the statement of fees charges. This was explained to the profession through a document produced by the Joint Emergency Committee (Optical Profession), which was sent to ophthalmic opticians and which contained the information for individual opticians entering the scheme.[25]

There was no centralisation of production or distribution and due to the widespread demand for appliances large numbers of manufacturing firms, both large and small, were producing frames to conform to the NHS range. During 1950 manufacturers were invited to send samples of their NHS styles for Ministry approval and a system of frame stamping and authorisation for NHS patterns was introduced in July 1951. Once approved a certified trademark was issued to indicate the design was authorised by the government. The introduction of this frame stamping system raised some concerns in the trade as wholesalers did not wish to be left with unstamped unauthorised designs, and these fears of the NHS scheme interfering with the supply system were indicated in the trade press (Optician, 1950). However, any manufacturer, importer or supplier (and this initially included any ophthalmic or dispensing optician who manufactured his own frames by hand) was entitled to apply to the Ministry of Health for the use of authorised trademarks. This meant that where a dispensing optician used a manufacturer or wholesaler to supply appliances this enabled them to retain their trading relationship.

From July 1951, all frames supplied for the National Health Service needed to be stamped with the NH trademark and the identifying letters of the firm. Government instructions to the maker decreed that ‘Henceforth all patterns of such frames supplied by him for National Health purposes must be stamped by him with both the trade mark and the letters identifying his firm’ (Giles, 1953). Manufacturers were to send three frames of each pattern to the Ministry and a certificate would be granted if the design was approved and the firm was given permission to mark their frames. The Ministry attempted to regulate quality and pattern of frames within the range with the limiting factors being the cost of production and the appearance of the frame; conformity to the range was important and innovation and fashion were eliminated. Should there be any variation in quality or pattern, and complaints made about this, the frame in question would be compared to the three samples previously held by the Ministry.[26] The Ministry issued lists of authorised manufacturers, giving the name of the firm, their letters of identification, and the type of approved NHS styles that the company produced. The first list was published in the Optician journal on 29 December 1950, prior to the implementation of strict regulations concerning supply of approved and stamped frames to start on 1 July 1951.[27]

When frame producers sent samples to the government for approval, the Advisory Committee on Spectacle Frames, part of the Standing Ophthalmic Advisory Committee, would group the samples in three categories which were decided in accordance with the following criteria[28]:

New frames should in the first place be judged by the criteria laid down in the statement of Fees and Charges, including the description of the frames and the standards of the quality and workmanship. Any frame which complies with these criteria although it might differ somewhat from the original pattern should be regarded as a variation of the appropriate type already included in the Statement. Any frame which does not comply with these criteria should be regarded as a new type.[29]

Variations were strictly assessed primarily in terms of quality and cost of production. They were rejected if they did not conform to the schedule of prices as were those that ‘would be more expensive to dispense or which would increase the cost to the National Health Service in any way’.[30] Any frames that were considered to be too modern or stylised were also rejected: ‘Variations which seem designed to set a fashion which might increase the demand for spectacles under the National Health Service will also be ruled out.’[31] If a frame with a slight difference was admitted there was no obligation on prescription houses to stock the different variations of that pattern. The inclusion of completely new types would only be considered after wide consultation with the industry. These rules for classifying regulation frames relied very much on the committee’s opinion of what constituted frames that might ‘set a fashion’. Consequently, the frame patterns which attained certificates for production according to the ideas of the committee resulted in a very limited range of patterns; these were based on established designs that would soon become dated and old-fashioned.

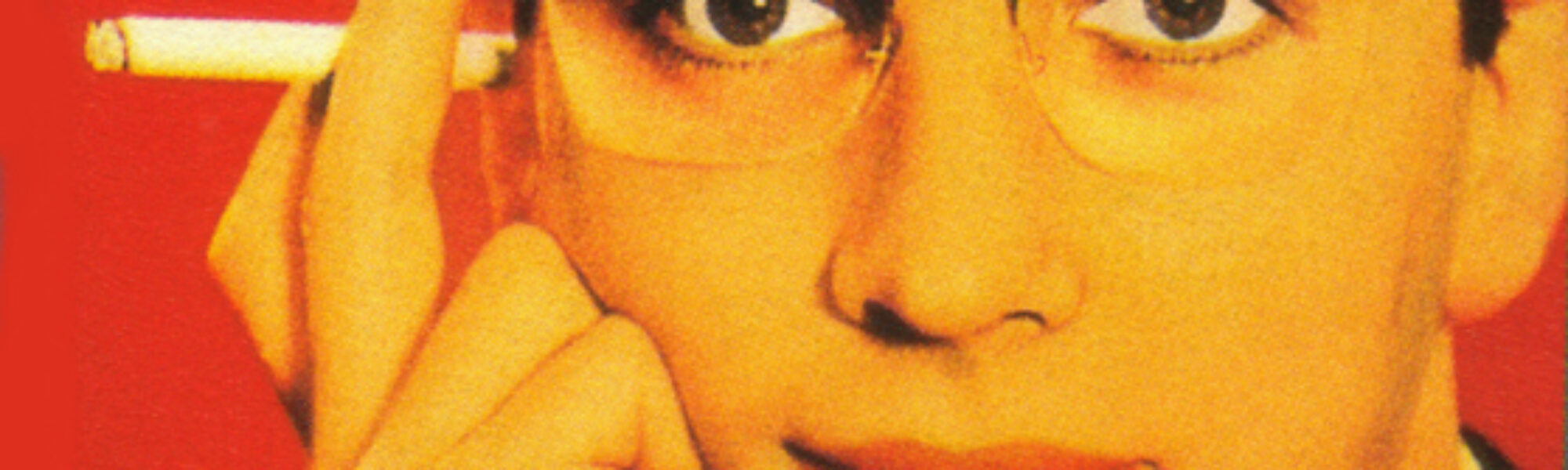

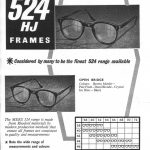

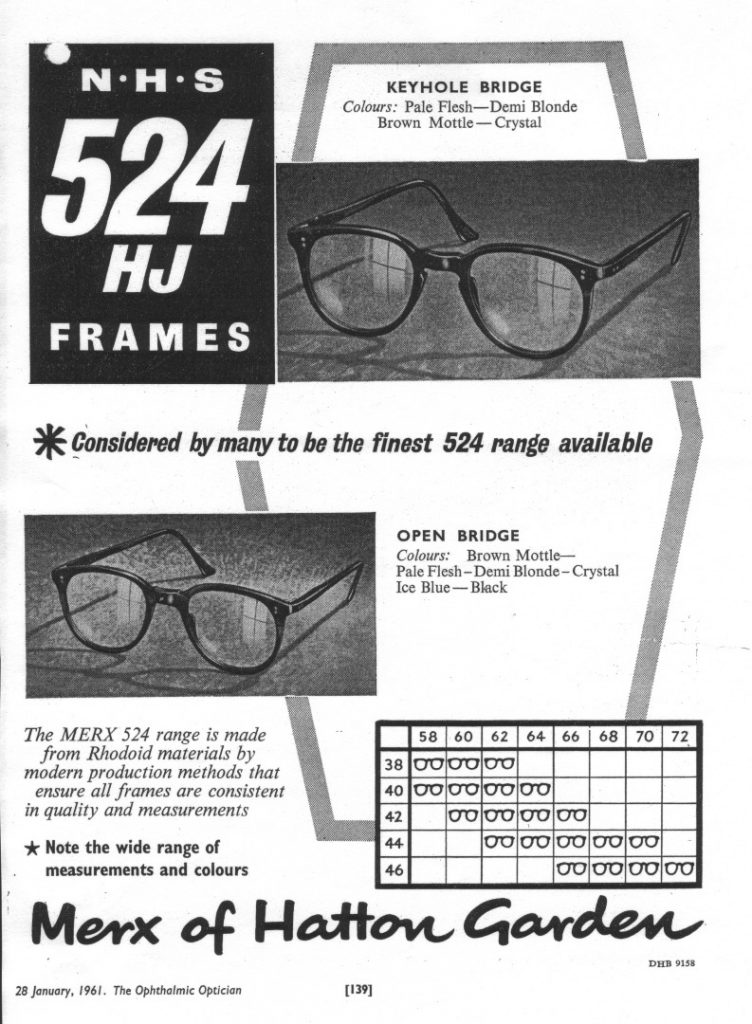

The production methods for metal frames made them suitable for manufacture in large quantities; this also made them ideal for fitting the criteria of the health service. However, there were also possibilities in Britain’s manufacturing industry to produce cellulose acetate (plastic) frames. A major concern for the government was that, while the optical industry would be able to meet demand, ‘a wider choice would upset the present levels of demand and the demand for metal frames would cease’.[32] This comment is particularly pertinent as it shows evident concern over the popularity of plastic frames in this period. Plastic frames were included in the range, but it was felt by the liaison committee that if they were placed within the free class of spectacles that the uptake would be immense and demand for the remaining types might ‘virtually cease’.[33] The new material was associated with progress, and in a brown mottled colourway it imitated the more expensive material of tortoiseshell, and as such had an allure.[34] One of the most popular plastic frame patterns in the scheme was number 524. This was produced in a range of colours and could have slight variations of bridge pattern.[35] The trade advert for Merx (see Figure 7 below) shows the different options produced, with both an ‘open’ and ‘keyhole’ bridge available, and proudly proclaims its wide range of colours to include Pale Flesh, Brown Mottle, Demi Blonde, Crystal, Ice Blue and Black.

Despite the popularity of the slightly more modern design of the 524 there was only a very limited array of contemporary design styles in the range. A representative of the Association of Wholesale and Manufacturing Opticians (Frank Wiseman, the chairman of manufacturers M Wiseman and Co. Ltd) had expressed his concern as early as September of 1950.[36] He wrote a personal letter stating that he was ‘seriously disturbed at the very narrow standardisation of spectacle frame patterns which has taken place as a result of the National Health Service’.[37]He was concerned about the effect this would have on the export industry, the development of the home market, and on the choice available to the public:

We see no reason why the public at home should not receive modern spectacles, always providing that they do come within the specification for quality and price as laid down by Ministerial regulations.[38]

The representatives from the Ministry of Health accepted his concerns for the export industry, and met together to discuss the issue, but no action was taken to update the appearance of regulation frames. Ministerial notes from 28 September 1950 stated:

[We] agree that this is undesirable and that it was never intended that the National Health Service should have the effect of putting the manufacturers of frames into a straight-waistcoat for ever and ever. We must, however, be careful not to admit a ‘fashion’ element which might easily increase demand unnecessarily.[39]

So, there was little scope for radical change, although there were no exact requirements on the visual appearance or shape of frames, and regulations were open to some interpretation. Durability and cost-effectiveness were key considerations of the government for production of the NHS glasses range; ideas of ‘good’ design aesthetics or fashion were of little importance thus the history of spectacle design is distinct from other types of industrial design in Britain during this period.[40]

From 1948 to 1950 the trade struggled to increase production and remove the backlog of people waiting for frames under the NHS scheme, so all assets were put into production of frames on a large scale. The circumstances were not right for considering innovation in frame design but the forthcoming Festival of Britain may have encouraged contributors to Optician to consider design and style. It is evident that the ophthalmic trade felt a sense of embarrassment at the lack of merit and innovation within their trade at that time, as this contributor to the Optician laments:

We wonder whether there will be any British spectacles thought eligible to be included [in the Festival of Britain]…so long as Whitehall retains a tight control of the types of appliances that comprise 80 per cent or more of the nation’s ‘consumption’ of spectacles, so long we fear must designers be inhibited and manufacturers deterred from tilling fresh ground.

In 1950 the main trade journal made a heartfelt request to their readership that action should be taken:

Has not the time come when people in all sections of British ophthalmics should combine in a determined effort to infuse some variety, some freedom of design and colour, some novelty of line and embellishment into the spectacles that are put on the faces of the ametropes?

Optician, 1950

The British optical trade’s contribution to the Festival of Britain in 1951 was an exhibition named ‘Britain’s Festival of Optics’. This exhibition was organised by the Association of Wholesale and Manufacturing Opticians as a large fair in order to cultivate international trade. The Chairman of the organising committee and editor of the Optician, W E Hardy, had a vision for the exhibition and used the pages of his publication to explain this to members of the trade: he hoped that the experience of it would be ‘both interesting, instructive, and stimulating at a time when a fresh inspiration is urgently and vitally needed by all those whose work is directed towards the betterment of human vision’ (Hardy, 1951). The article suggests that there was low morale among the manufacturing trade and that this might offer some stimulus to the industry as a whole: ‘…this 1951 trade exhibition therefore marks the beginning of the new, and what must be a hard and difficult stage, in our history’ (Hardy, 1951).

This assessment is understandably slanted to give a trade perspective and indicates the business concerns of an entire industry that was being restricted due to post-war conditions and the introduction of the ophthalmic services to the welfare system. These circumstances caused the optical practitioners to consider the status of their profession and the remuneration that they received from the government for their services. Whilst they acknowledged that the public undoubtedly benefitted, the professions who delivered the service felt that they did not.[41]

Trade and private frames

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/170703/006The provision of sight tests and supply of regulation frames under the National Health Service became the main source of activity, and of income, for ophthalmic and dispensing opticians during this period. The provision of NHS frames reportedly made up 80 per cent of business activity; optical practitioners were paid per patient seen and this brought a limited income stream which had to cover the overheads of their premises and practice costs. Practitioners who were affiliated to the NHS supplementary Ophthalmic Services (section 41, NHS Act 1946) needed to accept the Ministry of Health’s terms of service and to work within strict regulations. One restriction that had implications for both business practice and for the patient was the ban on advertising.[42] An optical practitioner worked within a practice or consulting rooms. This environment meant the purchase of the product was not defined in retail terms as a shop premises; opticians would not refer to their clients as ‘customers’ but as ‘patients’. It is through this rejection of consumer terminology, and the processes of retail trade, that optical practitioners identified themselves with the medical profession.

Within the optical industry, during the period 1946 to 1986, some of the key features of retail trade were consciously rejected; because advertising was strictly prohibited and the clear display of prices was forbidden under the scheme, any creative visual display of the product in a sales area was unusual.[43] There was little communication about the range of frames available within the state service and practices were also prevented from promoting alternative frames that were available under their private practice. Design and styling were not considerations within the NHS range – indeed, fashion elements were consciously rejected. It was only spectacles produced outside the system, in the private trade, where there was an element of choice. However, the terms of service prevented promotion of these choices.

The 1951 trade exhibition had highlighted this troubling issue; although alternatives in private frame styles could be promoted within the trade publications, how could information about these more fashionable frame styles, suitability of fit, and other elements of eyecare be communicated to the public? During the trade exhibition there was a meeting between W E Hardy, editor of trade journals Optician and The Manufacturing Optician, Max Wiseman and Frank Piggott, where it was agreed to begin an appeal to fund an information council for the trade (de Klerk, 1976). The Information Council of the Optical Industry, later the Optical Information Council, was founded in 1951 in an attempt to address the public ignorance of ophthalmic optics and combat prejudice against spectacle wear. The Council was fully aware that it had a difficult task ahead; they were faced with hostile public opinion, and members of the profession had to work within the Ministry of Health restrictions. The organisation was able to do this because it presented impartial general advice rather than promoting products for financial gain. The aim of the service was to educate and influence public attitude and this would be beneficial for the entire trade. However, the press officer, Frank Piggott, stated that the initial aim was to stimulate demand outside the National Health Service.[44] The Council organised a series of trade meetings across the country, was able to be supply information, and organised publicity campaigns and collaborated with British Pathe on the production of several pictorial news films for screening in cinemas. The series of short films produced in the 1950s are particularly interesting as they demonstrate the private frame styles available: the 1952 film Specs for Showgirls shows a spectacle fashion show and promoted flamboyant private designs using a glamorous model; the 1955 film Spectacles shows the importance of the relationship between optician and patient, where the optical frame fitter is presented as an expert who can ‘help enhance beauty’; and in a 1958 film female students at the Lucie Clayton Mannequin School are given instruction in choosing the right pair of spectacles for an occasion.[45]

The films and articles influenced by the Optical Information Council provide evidence that there was a negative reaction to spectacles that had to be addressed. Whilst these films from the 1950s identify that there is a huge potential market in women’s frames and they make consideration of fashion and attractiveness, they predominantly offered advice on correct fitting of frames from the standpoint of an optician, a skilled frame-fitting technician, and was the only outlet to promote trade in private frames. The NHS constricted the optical practitioners, the optical trade and therefore the market, which consequently had a limiting effect on the trade in private spectacles. The government scheme was seen as the limiting factor on design innovation in private styles; it was blamed for stifling opportunities for creativity and innovation. The government did not have an active agenda for design in the optical industry so it was left to individuals to innovate and do this in the private frame market. One individual who had already been working towards a design that offered variety was Neville Chappell.

A design innovation...

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/170703/007The main purpose of spectacles is to enable the wearer to see clearly, so the problem of lower eye-rims obscuring the field of vision was of concern. Neville Chappell addressed this issue and invented a new frame shape with a visible brow bar that had the lenses held in place with invisible straps.[46] This style was called the Supra and was the first fundamental change in spectacle frame types. The Second World War had seen developments in plastics, and especially a new clear strong plastic thread called Nylon. This was the ideal material to invisibly suspend lenses to the upper frame. Technical advances in the form of diamond impregnated copper bonded wheels made it possible to cut a small groove in the glass lens so that they could be suspended by the clear thread (Optician, 1989). Due to the post-war limitations on the optical industry in Britain there was little scope for manufacturers to produce this innovative new style of frame and there was no major production in Britain. Chappell allowed licence for production to companies abroad and the invention received huge popularity both in Europe and the United States and Optician referred to the Supra frame design as ‘a worldwide success’.[47]

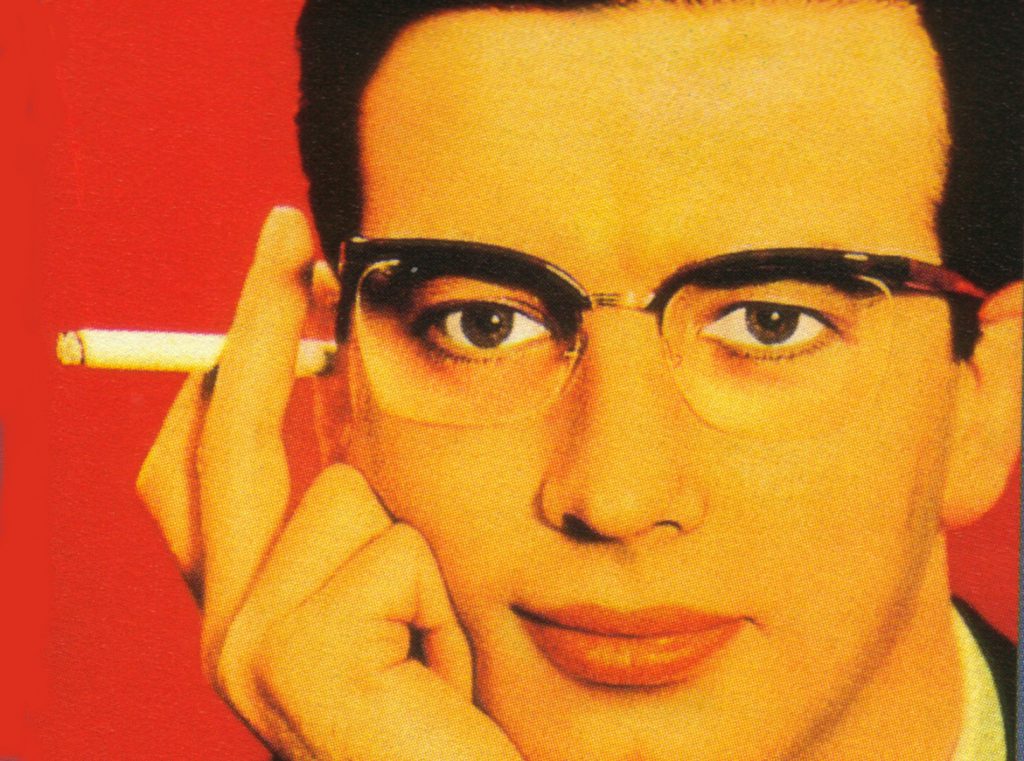

The design ideas behind this were used in other frame styles and developments in the colouring of plastic enabled an entire plastic frame to be tinted on the top yet left clear on the lower eye-rim to give a clearer field of vision. Frames such as the Brow-line and the Two-tone were produced on the private market; these two-tone frames were often called ‘the poor man’s Supra’ (Optician, 1989).

A design challenge – NHS hybrids and Regulation 12

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/170703/008The frames styles available under the NHS were very basic and to get a fashionable or stylish design of spectacles patients needed to purchase appliances on the private market. This could be expensive for a fully private frame and lenses. However, there was a compromise available for patients who were willing to pay for an up-grade of their frame and still receive state assistance for the sight-test and lenses. Frames known as NHS hybrids were available on the private market: the dimensions of the eye-rims were such that they could be glazed with regulation lenses but offered the patient a more stylish frame. A fashionable upswept or cats-eye shaped frame, similar to those shown in the Pathe film clip, was produced as a hybrid frame by Vertex Optical. Their trade advert for the Pussy Cat frame from 1960 explicitly states that this fashionable style could be glazed with regulation lenses and offers opticians reassurance: ‘The frame with the upswept look which can be glazed with NHS lenses. If you cannot believe this we can supply you with a stamped 524HJ from which the lenses can be transferred if necessary.’

The text from this advert suggests that the criteria for designing regulation frames remained an issue a decade after the introduction of frame stamping and trademarks. The issue was raised with the government when representatives of the ophthalmic trade, the Joint Committee of Ophthalmic Opticians, met with officers of the Ministry of Health in 1960. In the minutes of this meeting Mr Giles, a key industry figure (having published the guide to the NHS in 1952) made it clear that the optical trade sought extra guidance over the designs that were acceptable under the scheme. He requested the establishment of a body which would ascertain ‘whether individual frames conform to the National Health Service shape’. The reply from the ministerial representative suggested that the Standing Ophthalmic Advisory Committee fulfilled this purpose, yet it was clear that confusion remained.

Three years later, in 1963, frame manufacturer Michael Birch (Designs) Ltd tested the boundaries of the committee’s definition of what was acceptable for NHS patterns and also raised the issue of what constituted ‘fashion’. Michael Birch was known for producing fashionable Supra frames for the private market and he attempted to introduce slight variation to the NHS patterns with a design called Candida. This frame had an inner shape that could be glazed with regulation NHS lenses but the outer rim was of more fashionable style.[48] Birch’s Candida frame was not a Supra but used variation in the colour of plastic to give the appearance of these popular private frames. He believed the frame conformed to Regulation 12 describing NHS patterns but was initially refused a licence to produce the style (Optician, 1964). Frames of two colours were not allowed into the range – and this frame was two-tone. This unique case went to court as Birch appealed against the Ministry of Health’s refusal to grant a licence. The point of conflict had been the eye-shape and also the process of ministerial approval. Following lengthy evidence the appeal was upheld and the Minister was ordered to grant a certificate. Birch had managed to push the boundaries of what was acceptable.

The Birch frame had caused controversy as it was felt to be too stylish. The government was clear in its insistence that NHS frames should not be affected by fashion and trends. In internal documents from the Standing Ophthalmic Advisory Committee it is made clear that this was a factor under discussion. The elimination of styling aspects was an active deterrent and a deliberate attempt to limit the number of applicants for state aid. When a journalist investigated the lack of change in the NHS frames over a 22-year period both the government and the entire trade were criticised. In the February 1970 issue of Focus, the magazine of the Consumer Council, opticians were criticised for not demanding changes in the NHS range due to their own self-interest in selling more expensive private styles. Also that ‘opticians seem happy to promote the snobbery which regards Health Service as functional but second best’ (Optician, 1970). The report also found that the government seemed ‘surprised’ that the issue of poor design was raised, and that ‘they disliked the word fashion being used in connection with NHS frames, preferring the term “specifications”’ (Optician, 1970).

Fashion was seen as a powerful and threatening factor to the system of regulation frames. So much so that terminology relating to design principles was rejected. A frame was an appliance of a certain specification, referred to only by a reference code number.[49] The prerequisite for a state schedule frame was cost-effectiveness. When questioned about the limited designs offered by manufacturers Ministry of Health representatives in 1970 replied that, ‘manufacturers limited the scope of the 524 because they said they could not produce a better frame for the price they were paid’ (Optician, 1970). They did not acknowledge that the visual appearance of the 524 had not changed over 12 year and design had stagnated. Manufacturers also noticed the effect of the NHS terms of service on ophthalmic technology and frame design in Britain. W E Hardy, of the Federation of Manufacturing Opticians and editor of the Optician, stated the importance of design and that:

British ophthalmic manufacturers were among the first to appreciate the true significance of styled frames [but] their NHS commitments exerted a breaking effect on the designing and producing of novel spectacle frames.

The rejection of fashion and styling worked for the benefit of government financiers but to the detriment of patients and the optical trade.

Patient choice and information available

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/170703/009The amount of information available to patients concerning the NHS scheme was minimal. The speed at which the NHS ophthalmic services were introduced left little time for consideration of its implications. As the scheme followed the precedent set by Utility provisions, the attitude that the public should ‘make do’ for the sake of the nation still prevailed. Opticians were not obliged to show patients the full range of patterns available and there was little concern about public awareness and reaction.[50] The issue was raised by Member of Parliament Commander H Pursey in 1959, who complained that he could not to find information about the provision of health service frames or see a full range of frames available in order to make his choice.[51] Pursey’s concern over the lack of information provoked interest in the press. S W New wrote to the Ministry with a very simple suggestion that would provide clarification:

I think all the trouble over the question of payment for frames would be overcome if the Ministry would issue a leaflet showing illustrations (which only need to be in black and white) together with a list of colours available to the public under the scheme. One must face up to the fact that the optician is of course going to try to increase his business by selling more expensive frames. As you must be aware, the public do not know whether the optician is showing the full range of glasses available under the NHI.[52]

This statement was true; opticians did rely on the sale of private frames in preference to health service glasses as an extra source of income. The issue of display was therefore an important one. It would be to the patient’s benefit for there to be a prominent display case showing the full choice, yet this was not in the opticians’ best interests. Large displays of frames across the wall of the practice, the frame bars as we know from today, were not common in this earlier period. Frames were stored in trays that would be shown to patients. There are many references to NHS frames becoming ‘dusty museum exhibits in the hands of most opticians’ (Optician, 1964), kept in trays and boxes ‘under the counter’.[53] An article in the News Chronicle on 24 February 1960 expressed the worry felt over out-of-date NHS frames and the high cost of private fashionable alternatives.

Badge of poverty

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/170703/010The acknowledgment that frames were out of date had been raised in 1960 and a decade later this remained an issue of concern. The patient was in a very disadvantaged position in their role as a consumer, and in 1969 the Consumers Association took action on their behalf by reporting on health service provisions (The Times, 1969; Optician, 1969). The magazine of the Consumers Association, Which?, reported on a survey of health service spectacles claiming that they were outdated and criticising the lack of choice and the range of frames stocked by opticians. They stated that ‘the range of NHS frames is inadequate and out of date – not surprisingly opticians do not stock them all. Two-thirds of those buying spectacles pay several pounds extra on private frames’ (The Times, 1969; Which?, 1969). The report criticised opticians for promoting the more expensive frames to their patients; although it understood the reasons for this were that the NHS fees were not realistic enough to enable opticians to maintain their standard of living, the cost of which had ‘more than doubled’ since 1948. They suggested that ‘opticians might be less keen on private frames if NHS fees – which had only gone up by only five shillings 11d since 1948 – were more realistic’ (The Times, 1969). However, we can also see that opticians were giving patients the opportunity for a more styled frame by offering NHS hybrid styles.

Little action was taken in direct response to these complaints. However, the changing social conditions of the 1970s saw further concerns about the costs of the National Health Service and the implementation of the Welfare State. The 1970 the Conservative government extended the principle of means testing for benefit, and in this year the new budget introduced higher charges for health benefits. This led to an increased charge to the patient for optical services and costs for spectacle frames were now to include dispensing costs (The Times, 1970).

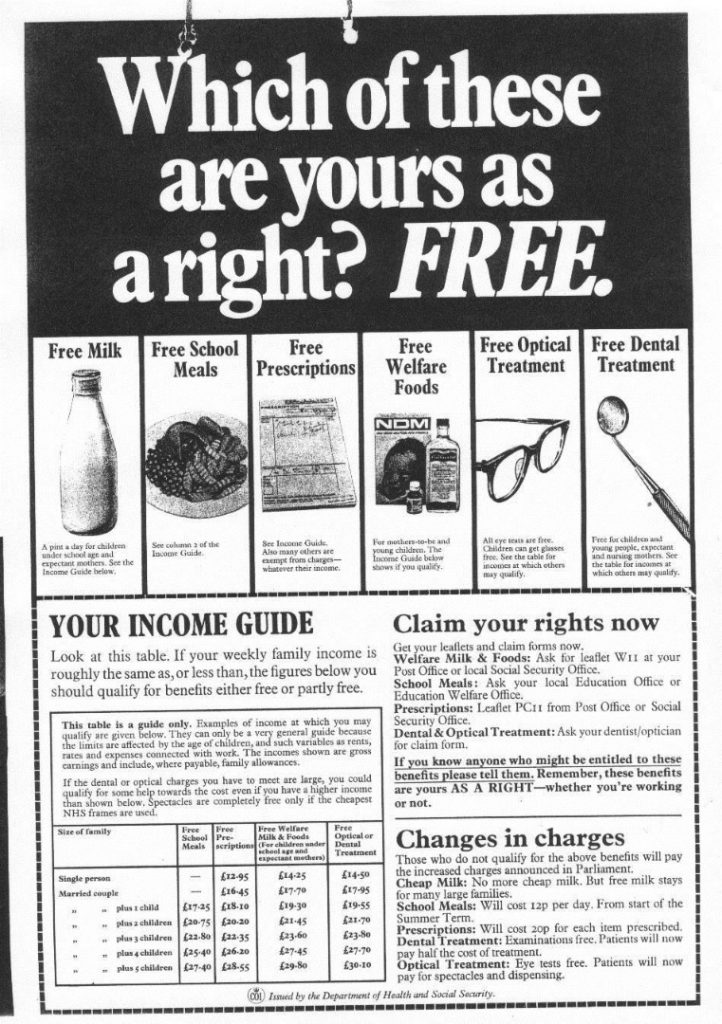

In 1971 a Labour government introduced leaflets and posters providing information to the public about the welfare benefits available to them; this was evidence of the Ministry beginning to demonstrate that the public should be given information directly from government rather than through the professional bodies.[54] These initial measures did not specifically describe the range of frames available, but informed applicants about entitlements. In 1972 there was a slight alteration to the range of frames available for children when ‘more attractive spectacle frames made from plastics will be introduced into the National Health Service free range for children’ (The Times, 1972). But there was no stylistic change in the adult range.[55]

The issue of appearance and fashion in frames, and the criticisms of the Consumers Association seven years previously, was openly discussed. Barbara Castle, Secretary of State for Social Services, addressed a conference of local optical committee representatives stating that the Department of Health may introduce better looking glasses on the National Health Service. They acknowledged that the limited range of NHS frames were unattractive and it ‘meant that people choose them because they could not afford the more attractive frames available privately’ (The Times, 1976).[56]

As she addressed the conference Mrs Castle explained that of the twelve frames in the NHS range most were designed to meet special clinical or minority needs. This resulted in one frame type, the plastic 524, being chosen by ninety per cent of people who were supplied with NHS frames. When the pattern was chosen for the range in 1948 ‘it wasn’t fashionable…but at least it was in fashion and not out of it’ (Optician, 1976). There had been minor variations on the appearance of the 524 but no major re-design. She acknowledged the significant changes in the optical industry over the thirty years since the range was introduced but that National Health Service frames had scarcely changed. The government now also recognised that spectacles were not merely clinical appliances but an integral part of the wearer’s appearance and personality. Although cost would always be a consideration, it was felt that ‘the therapeutic value of feeling one looks one’s best’ was also important in the state provision of optical aid. Mrs Castle said:

The nub of my point is that a good-looking pair of spectacles in which the wearer can feel self-confident is genuinely a need in a society like ours: it is a need which for many the NHS is not fulfilling. We must not force people to wear out-of-date frames like a badge of poverty across their faces.

Optician, 1976

These comments triggered many newspaper articles on NHS frames. Good looking frames were presented as ‘morale boosters’ in contrast to the NHS range as an indicator of low social status. Mrs Castle was eager to work with the optical industry as a whole to solve the problem. Prompted by letters from members of her constituency she expressed that she was ‘particularly concerned about those people…who are too poor to be able to afford the more attractive frames which can be obtained privately’ (Optician, 1976).

Whilst the Department of Social Services initiated changes in the NHS range the issue of inflated prices of private frames was being investigated. Later in the same year the ophthalmic trade was criticised in a report by the Price Commission (Price Commission Report, 1976). Their view was that the price of private spectacles was higher than it needed to be and that there should be ‘more competition between opticians and less reticence about prices’. It was further suggested that ‘the National Health Service should offer a greater variety of frames and that the opticians should ensure that patients are in a position to make an effective choice between NHS and private spectacles’ (Price Commission Report, 1976). Opticians were accused of not fairly representing the range of frames available under the health service. The findings of this report also suggested that patients were still left somewhat in the dark as to their rights under the health service. In the first thirty years little advancement had been made over informing patients about the workings of the state’s optical service. The fact that there had been little change in health service frame styles over the years further compounded the fact that when an optician demonstrated NHS frames it did little more than ‘drive people towards the private frames’ (Price Commission Report, 1976).[57]

Measures were taken over the availability of frames in 1977. Following debate in Parliament about the lack of competition among opticians the government acknowledged there was a problem in the display of frames. No measures were taken to solve the root causes: the poor design and choice of frames, which made them undesirable due to their uniformity; and the low fees paid to opticians for their services. However, measures were taken that forced opticians to stock and display the full range of NHS frames:

Opticians will in future stock and display the full range of National Health Service spectacle frames, under measures announced yesterday by Mr Hattersley, Secretary of State for prices and consumer protection. He said the ophthalmic organisations had also agreed that prices should be shown where frames are displayed.

The Times, 1977

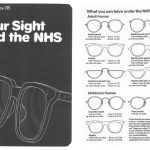

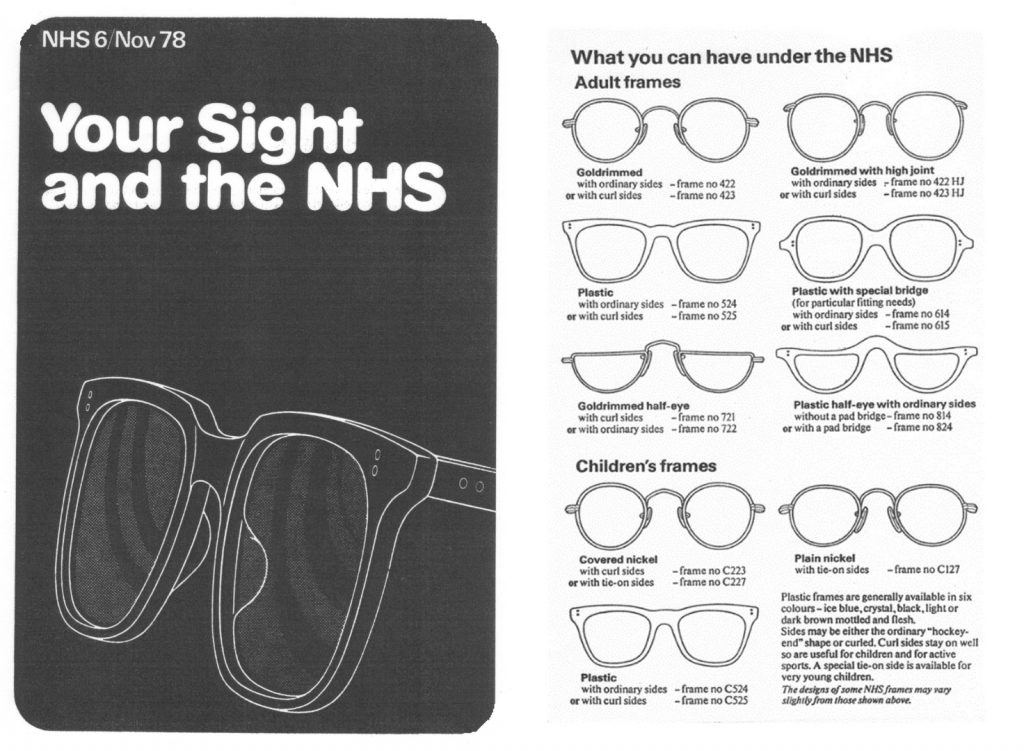

Giving information to patients was now seen as important. A leaflet that offered precise information about the schedule of frames was issued in 1978 (some eighteen years after a request had been made). NHS leaflet 6 was entitled Your Sight and the NHS. It described where NHS optical services were provided, how to get a sight test, and the entitlement to glasses.[58]

The confusion over the rules concerning the display of the full range of scheduled frames under the National Health Service was clarified when the terms of service for opticians under the health service were amended in 1980; and following this a glazed case containing examples of frames available was produced. The government had also issued a leaflet containing illustrations of National Health Service frames and giving information on patients’ rights and what they would expect to pay. It was raised in parliament that it had taken the government 32 years to fully explain the public entitlements under the National Health Service; this had mainly been due to confusion over whose responsibility it was to inform the public of their rights to optical aid (The Times, 1980). The consumer was becoming a force in Thatcher’s Britain.

End of the scheme

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/170703/011In 1982 the government took the unusual measure of changing the range of health service glasses available by introducing the first new frame style to the range, the ladies plastic two-tone frame with pattern number 924. This was the first of many significant changes which sounded the death knell of the National Health Service frames range. This again had a huge impact on patients, and on the optician business. On 1 April 1985 some more wide-ranging changes entirely affected the way opticians did their business. They were allowed to advertise, price their frames, and enter a free marketplace. Relaxation of rules came with some changes in the NHS eye service administration; a voucher system was introduced for those who were entitled to aid. This extended the principle of means testing for patients. Further opportunities were available for an optician in business terms, and within a year over one thousand new optical shops opened, offering wider choice to the consumer and triggering the beginning of fierce high street competition (The Times, 1986). The position of opticians and their businesses had widely changed, and brought a new era of opportunity for patients. This also opened up the market, giving the opportunity for a much wider influence by fashion and designers.

NHS frames style revival in the twenty-first century

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/170703/012The discussion of design change and its associated histories of fashion trends and styles is implicit here, although it is relegated to the limited private market in Britain during this period. Fashion histories of glasses predominantly consider sunglasses or frames produced for the European or American market (Murray and Albrechtsen, 2012). The complete change in administration of eyecare and provision of glasses brought circumstances for development of new fashionable styles of eyeglasses. With historical distance, scheme styles from the NHS range of glasses are being re-invented and have fashionable appeal for a new generation. Many of the frames that were produced to be durable, practical medical items under the scheme have survived. As Neil Handley, curator of the British Optical Association Museum notes: ‘The high quality of NHS spectacles has meant, however, that many frames have survived to the present day and they have now taken on a new identity…as desirable retro-chic eyewear’ (Handley, 2014). The frame style 524 has particular appeal and is also being reproduced by new manufacturers; and there is a popularity of the style in markets abroad. The fashion trends for vintage or retro styles have contributed to this popularity; fashion historian Elizabeth Guffey discusses the theory behind this trend in Retro, and examples can be seen in the literature for spectacle collectors by Andressen, Murray and Albrechtsen.[59]

Conclusion – my hopes for future research

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/170703/013The provision of optical care to the British public under the National Health Service during the period 1946 to 1986 had a restrictive effect on the entire optical business and profession, affecting the business and professional activities of ophthalmologists and dispensing opticians, and the commercial activities of frame manufacturers and prescription houses. This had huge repercussions for the design and style of spectacles available to the population of Britain by severely limiting the market. Although both the government and the optical industry acknowledged the existence of a ‘fashion factor’ in frame selection, government concerns were with the cost-effective delivery of basic medical appliances while opticians were focused on providing professional eyecare and running a profitable business.

The range of NHS spectacle frames produced during the period 1946 to 1986 was provided as a functional medical appliance; ‘fashion’ and styling were consciously rejected for fear of increasing demand and raising the cost of delivering eyecare under the National Health Service. There were a very limited range of frames available and no significant changes to the patterns included in the range over the majority of the period. This contributed to NHS frames being a social marker, a ‘badge of poverty’, with a stigma attached to them. Within the range of state regulation frames there was no active concern for ‘design’ in terms of appearance and it was only through the purchase of private frames that significant choice and variety in eyewear could be attained. The scope for the public to select more fashionable frames whilst receiving an element of state aid was through the purchase of NHS hybrid private frames. State intervention in the optical market affected the design, production and distribution of all types of spectacles while the terms of service for optical practitioners in turn affected retail and distribution, having an impact on the patient as consumer. There were attempts at innovation by British designers when changes in materials and production methods offered potential for design change; Chappell’s Supra style was recognised on the worldwide stage due to the production of these frames for the European and American market, and Birch challenged the establishment by introducing the stylised Candida frame as a NHS hybrid frame.

The story of National Health Service spectacle frames is inextricably linked to the context of its time; due to this unique set of circumstances, a comprehensive analysis of these objects in terms of their production, mediation and consumption is currently unattainable due to the business, commercial and professional restrictions upon the market, the absence of representations of NHS wearers from visual culture due to restrictions on advertising, and also the negative associations and memories held by several generations. There are still important stories to be discovered relating to the experience of consumption of NHS glasses, wearing them due to necessity or as a contemporary ‘retro’ style statement, and the symbolic nature of NHS spectacles and how they contributed to identity.[60]

Tags

Footnotes

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text