Technologies of Romance: looking for ‘object love’ in three works of video art

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191209

Abstract

In this paper the author discusses three works of video art featured in the Technologies of Romance symposium held at the Science Museum, London, in 2018. The author searches within video art, as a genre or medium, within its technical apparatuses and within the three particular works, for contributions to the particular notion of ‘object love’ as drawn from a paper by Hilary Geoghegan and Alison Hess (2014). The author interprets the three video artists’ works with the aim of gleaning comparative examples that might illustrate or extend the ‘object love’ concept. Mathilde Roman’s book (2016) on the ‘staging’ of video art is an influence on the text, as are two short but profound statements by Walter Benjamin, one from his Theses on a Philosophy of History (1940), another from his essay on Surrealism (1929). History, ‘the past’, museology and ‘object love’ are all woven into the core of the article. As it moves towards its conclusion the author is inspired by the image of an empty, machine-made stocking (a classic symbol of Freudian fetishism) in Elizabeth Price’s video K, in such a way that the article ends by skewing both the idea of ‘object’, and that of ‘love’ in the direction of the fetish, while concluding that the past – just as much as any particular object from or of the past – tends to be subject to fetishisation. Meanwhile, video’s relative immateriality as an art medium, and its current use by artists, is seen as representative of an age of image-based archival practices that, assisted by digital technology, might now divert traditional, object-based processes of the museum – a shift that might be summed up in the phrase ‘screen becomes vitrine’. This shift, from vitrined objects to screened images might then, in turn, have implications for the ‘object love’ that initially interested Geoghegan and Hess and which began the author’s article and this dialogue with the Science Museum.

Keywords

Fetish, History, Museum, romance, Technologies, Technology, Video Art, Vitrine

Introduction

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/…we echo Carey-Ann Morrison and her colleagues, when they write: ‘We think it is timely, then, for love to be taken seriously as a valid and crucial subject’. They encourage researchers to ‘formulate new kinds of love that may create more ethical relationships with others [not just people in this instance, but museum objects]…as well as places associated with feelings of love’. We do so by acknowledging the central role of affect, emotion and love to the experience of the storeroom and its objects.

In my presentation for the Technologies of Romance symposium at the Science Museum, London in November 2018, I invoked certain thoughts and words of Walter Benjamin (see below) to preface allusions to history, technology, museology and ‘romance’ found in the work of Turner-prize winning video artist Elizabeth Price. Here I have expanded that short paper to first incorporate some reflections on video art as a medium and in general. I then discuss all three examples of video art featured in the symposium – works by recent graduate Rosie Carr, emerging artist Bada Song, and by the more established Elizabeth Price, followed by some conclusions.

In pursuing these lines of thought I became increasingly interested in the question of what relatively immaterial video art might bring to questions and explorations of ‘object love’ – a theme discussed by Science Museum researchers Hilary Geoghegan and Alison Hess in a paper titled ‘Object-love at the Science Museum: cultural geographies of museum storerooms’ (2014) (see introductory quote above). This paper came to my attention at the very first stages of discussing a collaboration with curators at the Science Museum. The aim was to create an event (which ultimately became the symposium) related to my recent writing, thinking and teaching on the theme of Technologies of Romance. Now, having enjoyed the rich experience of hearing several Science Museum researchers and other contributors to the symposium expanding on the theme of Technologies of Romance, it feels apt and satisfying to return to Geoghegan and Hess’s assertion of ‘object love’ at this late stage of reflection and consolidation.

In the works of the three video artists discussed here contemporary artists are seen to use the particular qualities and capabilities of digital video and video art as a vehicle with which to communicate contemporary tales of humanity and inhumanity. Between them they feature humour, anxiety, eroticism, nostalgia and pathos, and also expose technology as both disabling and enabling. Furthermore, they draw attention to our individual and collective plight as modern human creatures who make machines in the hope of leading more effective and leisurely lives but who then search with difficulty for adequate means with which to satisfactorily commune with those same machines, to share our world and our lives with them. The analysis of the artists’ individual works exposes their affective and empathetic potential and gradually leads into considerations of how video art’s archival tendencies might shed light, not only on our affective relationship with objects but on wider issues of history, museology and our relationship with ‘the past’.

Despite what might initially seem to be the relative immateriality of video art, the rich and often emotive content of these three artists’ works therefore prompts further thought about affective, actual, and tactile relationships between humans and objects, people and museums in the twenty-first century.

Video art

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191209/002The three principle artists referred to in this essay – Elizabeth Price, Rosie Carr and Bada Song – all use video art to deploy sensual, historical, political, comic and ironic episodes. If we look more carefully at their work we can also locate a special kind of sentiment, gravitas and profundity, as well as certain affective and emotional contents that might be accessed via the particular qualities of video technology. These artists share the special format of the gathered or created, edited and projected video image, a particular ‘generation’ (in both senses of the word) of moving image, accompanied by sound and now, thanks to easily accessible technologies, conveniently available for manipulation by artists in ways unknown to previous generations.

Although video today might not yet be as popularly utilised and deployed in popular contexts as the more ubiquitous still, photographic image, we seem to encounter it as an increasingly accessible medium. Despite its hi-tech image and currency, video could be said to occupy a historical realm somewhere between the magic lantern, cinema, the slide projector, TV, and today’s digitally animated images enjoying easy proliferation via social networks. What we now call ‘video art’, appeared initially in the late 1960s and early 1970s (Biesenbach et al, 2002) and became commonly used in the millennial generation of artists’ works. It might appear relatively immaterial, delivered as a light projection on a monitor or screen and generated by the readily transportable form of a tape, disk or file; however, this apparent immateriality belies the various, relatively cumbersome devices and contexts that might be necessary to its production and display.

In a landmark exhibition at Raven Row gallery, London, 2010, artist Hilary Lloyd raised her profile as an artist by noting a contemporary prevalence and tendency of video equipment to take on, in gallery spaces, a self-conscious, perhaps sculptural or even animistic presence.[1] Today, we encounter, in art galleries and museums, many elaborate references to video’s various modes of installation and projection, some of which may come to compete with, and sometimes even overshadow, the work being projected. In her recent publication On Stage: The Theatrical Dimension of Video Image (2016) Mathilde Roman redraws the contemporary art gallery and museum environment as something significantly transfigured by the onset and proliferation of video art. Roman makes us newly aware of the unique ramifications of video art, in terms of its image, narrative, presence, apparatuses and the particular kinds of display contexts that have evolved to accommodate, enhance and serve video art and its audience.

The paraphernalia required to present digital video might then loom large as its potential ‘object’ and yet may not be worthy of our ‘love’ (to persist with Geoghegan and Hess’s terminology). Nevertheless, concentration on the apparatuses of, and elaborately contrived contexts made for video art may also disguise less obvious ‘objects’ pertaining to it, or typical of it, and with which we might develop some form of empathetic or affective relationship.

In itself the video image might be relatively vulnerable and frail. When shown on a monitor or projected on a screen it remains subject to several contingencies of the environment, including the appropriateness of the qualities of the screen, the darkness of the room, the brightness of the projector, the quality of the lens, the efficiency of the media player, the quality and volume of the amplified sound heard through speakers or headphones which might, again, be of varying qualities. Then there is the correct or incorrect adjustment of the projector’s or monitor’s ratio and proportions to comply with the ratio and proportions of the original image, plus any competition that might occur between the projector’s or monitor’s light and other lights that might fall on the screen or distract the audience in other ways.

However, where and when we find such vulnerabilities and contingencies we might also find clues and traces related to our theme of ‘object love’. It is after all here, in these material concerns, that we can begin to locate affective and empathetic principles whereby we might be ‘touched’ by a certain care, sensitivity and empathy for, if not the mechanics involved then at least for the vulnerable video art itself, and its implicit appeal to be adequately and accurately presented.

The initial gathering of images for video art, whether newly recorded or gleaned from archives, is influenced and informed at the earliest stages of composition by consideration of their eventual redeployment in detailed layers and finely wrought sequences of ‘clips’ edited and projected on a screen, often in a dark, or darkened room. Today’s video art, no matter how sophisticated it may be in terms of current technology or the currency of its content, is connected to an uninterrupted technological history that includes the histories of cinema, TV and photography, modern media that are themselves informed by literature, and painting. And so, if we pursue a genealogy of video art back far enough we could perhaps trace and connect it to art’s assumed origins in cave paintings – more or less animated images, projected, suggested and in some way conjured by flickering light on walls in dark spaces.

Video art is imbued with a particular sense of intimacy, as well as being evocative of a certain atmospheric ‘gloom’. Inheriting and extending some of the aesthetic and technical legacy of cinema, video art brings that legacy (also influenced by the more domestic realm of television) into play as the outcomes of video production (the intricate gleaning and weaving of almost immaterial sonic and visual minutiae) are projected in spaces that produce a special sense of privacy and proximity, often involving (as Roman discusses) relatively small audiences or individual encounters in carefully darkened, sonically prepared and otherwise strategically constructed spaces, often including appropriate seating.

While ‘object love’ might not be the first concept we think of when encountering video art, I have nevertheless begun to draw out video art’s particular and peculiar properties and propensities in such a way as to embody and transmit certain values of intimacy and affect. Having posited this as a common ground shared by the three video artists, I will now proceed by explicating their individual works and practices.

Rosie Carr’s The Photocopier Who Fell In Love With Me

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191209/003The title of Rosie Carr’s The Photocopier Who Fell In Love With Me (2018)[2] promises amusement, but the piece is only superficially comic. While its audience is bound to grin at certain points as well as at the general conceit, the piece might also remind us that a joke once applied to or deployed within art, is not necessarily as funny as the same joke deployed in life.

In the work, a voiceover reads an intimate confessional monologue relaying a young woman’s barely repressed passion for an efficient and (literally) warm photocopier working away in the corner of the office where the woman is employed. There, the workers (whom, we might assume include the artist herself carrying out the kind of ‘day job’ familiar to many recent arts graduates) are forced to execute dull, repetitive, far-from romantic routines and duties that might seem trivial and ‘beneath them’. If this is a love story, however, its narrative remains unfulfilled as something born on one side of the imagination of a bored human being, and on the other by a machine unable to express itself despite its apparently ‘skilled’ or ‘intelligent’ attributes and actions. While there is something absurd and incongruous about the barely repressed eroticism suggested here by Carr this is surely not dissimilar to the commonplace fetishisation of commodities on which much of modern, capitalist, consumerism depends (and this issue of fetishism will return, towards the end of this article with respect to the work of Elizabeth Price).

As ‘consumers’ we know all too well how cars, shoes, clothes, electronic devices, etc. may all be fetishised along with the status they supposedly signify and impart to their owners, and if this fetishisation does not erupt unprovoked within us then it is artfully cultivated and encouraged by strategic advertising. Thus consumers do build quasi-romantic, quasi-erotic relationships or even ‘love affairs’ of a kind, with objects and devices, pursuing narratives that can involve desire, sycophancy, unattainability, prohibition, attainment, dependency, obsession, loss, grief, and regret. For many, our mobile phones are said to be the first things we touch each day and the last thing we touch before retiring at night. This kind of sociological awareness of the impact of new technologies is well demonstrated in the work of Sherry Turkle (2011).

With the dawn of the industrial revolution Romanticism sought, in various ways, to alleviate, articulate and compensate for human traits and passions detained and diverted by modern, unnatural, unseasonal and exploitative mechanisms, found first in mills and mines but arguably also evident today amid our proliferation of computers, keyboards, and spreadsheets. In the same spirit, Carr’s video subtly implicates a twenty-first century office worker who, in repressing more disruptive responses to her condition, finds her most sensuous and affective nature diverted by the possibilities of a machinic office romance, one that is less likely to disrupt the efficient schedule binding the worker to her task, and also less likely to be seen as incongruous to her official role and position.

Carr thus uses the relatively immaterial medium of video art to proliferate a simultaneously tragi-comic, profound and political scenario, involving pathos and empathy while portraying dehumanisation and making an appeal for sensuality and sensitivity within a harsh and unfeeling environment. Despite being intimate and personal, Carr’s video alludes to a more or less brutal and banal incarceration experienced by billions of low-skilled, office workers worldwide, caught in the nexus of ‘9 to 5’ jobs, bound to high-rent or restrictive mortgage regimes. These incarcerated lifestyles tend to be relieved only by the prescribed, Orwellian provision of ‘happy hours’, ‘package holidays’ and ‘weekends’, as well as by fast food, online dating, and ‘couch-potato’-style streamed TV entertainment. Thus, inescapably tied-in to their suburban commuter community, the ubiquitous standing commuter or ‘strap-hanger’ becomes a quasi-automaton who might eventually come to approximate the office machines that they have come to serve just as dutifully as their landlady, boss, and the overarching regime of modern, technologised capitalist consumerism.

As we watch Carr’s video we might well come to award ourselves (along with the photocopier and the office worker) the status of an ‘object’ in need of ‘love’, or ‘self-love’ because it reminds us that our deep emotional need for care and companionship is all too often diverted, deferred, mediated, commodified and manipulated by external demands and inhuman technologies. Such technologies promise to help us by extending our abilities and thus challenging human limitations only to turn us away from admiration for ourselves, our fellow humans and from humanity and direct us instead towards admiration, affection and even ‘love’ for the technologies themselves as they monopolise our attention, enslave our gaze, occupy both our time and our hands, and apparently exceed us in their prescribed ability to speedily fulfil our particular needs.

The Photocopier Who Fell In Love With Me uses the particular propensity of video, and video art to record, edit, construct and transmit a moving and sonic image of an everyday scenario within which intimacy and affection unfold in surprising ways. A crossfire of emotions results from a closely explored dialogue between the technology of video art, the technology of office machinery, the surreptitiously engaged persona of the office worker, and ourselves, the audience, as we are drawn-in to feel the barely suppressed sensuality latent within these human and post-human exchanges.

In Carr’s scenario, surprising relationships strike-up between humans and objects, but these are perhaps not distinct from the ‘object love’ experienced by the visitor to, or curator of a museum, as referred to by Geoghegan and Hess in the introduction above.

Bada Song’s SEND-IT

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191209/004

In Bada Song’s SEND-IT (2014)[3] the artist is depicted as an isolated, estranged, perhaps alienated and therefore a possibly Romantic figure. We see a lone woman, the artist herself, seemingly entrapped within a succession of quasi-bucolic landscapes, replete with grass, hills, trees and narrow paths that taper towards a horizon. The paths run by the artist are recorded and edited in such a way as to appear to intersect and overlay. Meanwhile her plodding, robotic and inexpressive actions seem to tolerate and passively comply with (rather than overtly challenge) the demands made by her surroundings. Jogging along, seemingly without haste or expectation, Song nevertheless quietly and modestly appeals to her audience (to whom she never turns her face) while doggedly persisting, in hope perhaps of some kind of eventual recognition, rescue or redemption.

The artist’s slightly mechanical movements are also reminiscent of silent movie characters like Charlie Chaplin or Buster Keaton. She runs constantly, and apparently purposefully, yet also randomly, up, down and across the screen and sometimes running on the spot. Occasionally she runs vainly after her own technologically doubled video image, but never in any particularly sustained direction, and thus never arrives anywhere. Given Song’s status as a Korean artist resident in London we could interpret these actions as allusions to flight and the plight, not only of an emerging artist seeking support and acknowledgement but also – more poignantly and politically – that of a diaspora artist negotiating foreign climes, contexts, languages and cultures.

Any twenty-first century ‘diaspora artist’ (here defined as one living-out and working-out a narrative of cultural, national or class migration, often working, by choice or necessity far from their original national, linguistic and cultural context[4]) might experience a mix of conflicting desires that (on one hand) aim to draw attention to, and appeal for empathy with their diasporic condition, but also (on another) seek to disassociate themselves from any explicit connection to the context and concept of ‘diaspora’, as this can create prejudicial, presumptuous and restrictive responses to their work, leading to typological ‘pigeonholing’.

The option of refusing any such ‘diaspora’ labelling might leave the artist in a kind of ‘non-space’ or limbo, unsupported both by the power structures of the culture and nation from which they have migrated and equally unsupported by any compensatory local structures that might be provided to diaspora artists by the culture and the nation to which the artist has migrated. The artist-migrant or diaspora artist then, in Song’s SEND-IT, is portrayed as simultaneously unable to connect and wary of connecting. It is for this reason perhaps that Song has portrayed herself as always ‘on the run’ and getting nowhere fast. In this way Song’s video (like Carr’s above) is imbued with a personal and political pathos that belies a slightly comedic central image, in this case the Charlie Chaplin-like episodes and adventures of the lone migrant-artist or diaspora artist as a vainly striving figure.[5]

Throughout Song’s video, any love, affect or affection we might feel for an object is surely reserved for the ‘object’ of the artist herself. However, Song’s portrayal of an anonymous and inexpressive figure provides a ‘blank canvas’ onto whom we are able to project our own experiences of physical or emotional isolation. Thus we are invited to empathise, and any such empathetic response might well compel us to want to rescue Song’s seemingly wayward and undirected figure from the threats, dangers, disorientations and insecurities of the strange environment in which she finds herself.[6]

If SEND-IT reveals Song’s vulnerable humanity and identity located in the midst of a cultural conundrum, it also (as does Carr’s video) locates twenty-first century humanity as caught-up in a nexus of coercive technologies. If we interpret Song’s video in general human terms rather than individual terms, the plight of the emerging twenty-first century ‘diaspora’ artist might symbolise the plight of all those who are increasingly pushed by our economic and technological environment into insecure, nomadic and alienated ways of living and working.

Juxtaposed against SEND-IT’s slightly tainted pastoral scenery the viewer also experiences a cacophonous, discomforting and provocative soundtrack, brimming with a barrage of all-too-familiar technological noise. This complex array of gleaned and edited noise is set starkly against the video’s green landscape and alerts us to the harshness of an inhumanely technologised environment that has recently and rapidly crept over us, becoming commonplace in our twenty-first century world. We hear teenagers chattering and laughing as they exchange a barrage of text messages (connoting the work’s title SEND-IT) and each message is received with a loud simulated whistle, suggestive of a dog-call and evocative of a projectile hitting its target in a whirling war of abbreviated and predictive texts. Competing with the harsh tone of supermarket checkout bleeps, so symbolic of our increasingly technologised consumer society, we also hear interpolative ringtones that remind us of the constant state of alert that characterises our newly Pavlovian lives.

While ‘new’ or ‘hi’ technology here seems like a pervasive and pernicious imposition on the artists’ environment it also provides a means by which the artist – seen in the video using Google Maps – might try (virtually at least) to escape the moribund pattern of her lone roaming and vain striving. Thus, Song is seen using her smartphone as a tool within her artist’s studio, stroking and pawing the screen while reciting the names of places along a virtual journey. She uses Google Maps to imagine and visualise herself flying over and across, first Europe and Russia, then Mongolia and China, on and on to (virtually) finally reach Korea, her home country.

Throughout this imaginary homeward journey, Song’s compelling voiceover reconnects her present experience with her childhood memories; with her estranged homeland and culture; with memories of childhood journeys and earlier migrations in the history of her family; until she is finally (imaginatively) reconnected with her mother. Song then ends the sequence by emphatically crying out “Omma!”, the Korean word for ‘mother’ and an ur word within which might just lay the original, maternal source of all language and of all ‘object love’, concealed at the heart of each and every human being and human culture, and at this point we might be tempted to conclude that, just as no ‘diaspora artist’ is ever able to fully assimilate into the new surroundings of the class or culture or nation to which they may have migrated, so there is also a part of every migrating artist (and perhaps the most intimate and most crucially personal part of all) that never completely leaves home (Maland, 2007).

Ultimately Bada Song’s SEND-IT utilises the facilities and conveniences of pervasive, affordable, readily available digital video and smartphone technology to conjure a persuasive emotive appeal. This appeal initially seems highly subjective and personal but soon opens out to implicate not only all migrant-artists or diaspora artists but also all who choose to, or are forced in one way or another to migrate.

SEND-IT provides us with another possible interpretation of ‘object love’ as something central to every human being in the form of our emotional connection to self, to others, to place, to home, to identity, community, family and also to mother (where all ‘object love’ possibly begins) and thus to our unavoidable sense of placement and displacement, belonging, welcome and sense of being ‘at home’ within our physical, cultural and technological environment.

Elizabeth Price’s K

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191209/005

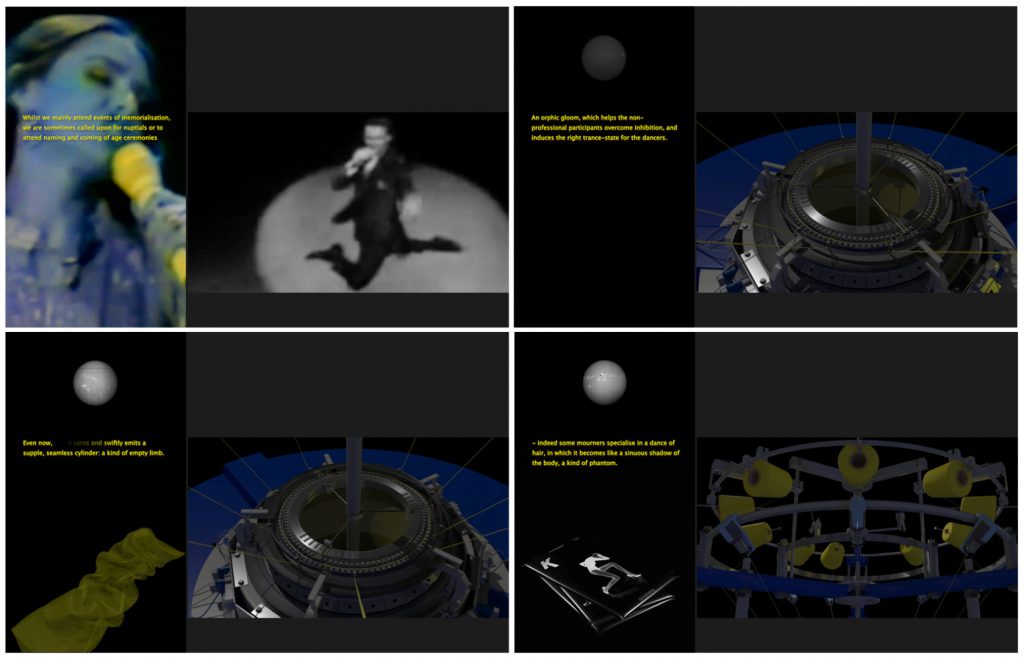

Initially Elizabeth Price seems to eschew revelation of any intimate self that might be operating within or behind the scenes of her video art. In K (2015)[7] she juxtaposes grainy found footage of 1960s pop singers against a digitally animated image (whose provenance is unclear) of an apparatus for weaving stockings. These two very different images – the former undeniably historical, the latter so new and unfamiliar that it appears inaccessibly futuristic – may at first seem incongruous, but as we watch the video and listen to its soundtrack (which includes some vaguely didactic lines of text spoken by a robotic voice) we can slowly come to feel that a synthesis of the two is possible.

Unlike Carr’s video (or certain elements of Song’s) there is little sign of humour here, but there are entertainments of other kinds. We are asked to consider the possibly ancient cultural roots of the pop singer’s shamanic role. Price’s text invites us to see her performers as ‘professional mourners’ who perpetuate a ritual function, both for the society of their heyday and for our own age of the digital archive that enables their resurrection. The fact that the singers in K are not contemporary but part of the past and possibly already dead and mourned themselves, is part of their sensual appeal. The past casts its particular spell over these images and thus over the viewer, by means of artfully chosen clips and sophisticated edits enhanced by carefully composed and captivating sounds, words and music.

Price’s video subtly suggests that we fetishise the past as an object, along with any particular object of or from the past. The outcome is an unrequited longing that may just be another form of ‘object love’. We treasure what we find in the past as a valued connection to and compensation for irretrievably lost time itself, and in this way each historical image or object becomes a fetish, standing in for time that we have lost and for which we quietly and perpetually mourn, just as for a lost love or a loved one. It is perhaps worth noting at this point that the traditional museum, displaying treasured objects isolated at arm’s length within secure, transparent vitrines, exacerbates this notion by setting up serial scenarios of loss, desire, partiality, unattainability, distance and denial.

Any ‘object love’ we might feel for surpassed image technologies and the images produced by surpassed technologies affects us in Price’s K by triggering an inescapably passionate response at the sight (‘or site’) of the physical evidence of the loss of a time. This is a time that we might perceive as ‘ours’, and thus presume to own, a ‘popular time’ that accommodates popular history and a history of popular culture. Though dwelling in the twenty-first century we remain closely connected to those earlier modern people depicted in Price’s video, born like us into with the modern age of highly technologised, capitalist, and consumerist democracy.

The archival imagery assembled and deployed by Price maintains a strange allure, seduction and sensuality. However, like a twenty-first century museum’s display of early modern technologies, they do not so much confront us with a radical otherness (or alterity ) that might result from the vastness of time that separates their original moment and culture from our own (as might be the case in, for example, the Egyptian section of the British Museum), rather, they inhabit and embody the lost time of our own lives, our own lost youth, and the passing of recent forebears. Such objects and images are thus imbued with the time of modernity, to which we feel not only intrinsic, formative attachment but also loyalty, responsibility and obligation.

Walter Benjamin, in his late work Theses on a Philosophy of History referred to this when he stated that:

The past carries with it a temporal index by which it is referred to redemption. There is a secret agreement between past generations and the present one. Our coming was expected on earth.

Here we can find an understanding of our implicit responsibilities to time and history. Benjamin’s words explain a slightly mysterious task set before every one of us to, in one way or another rescue, retrieve and redeem what will soon become the past in order to make the future available to unknown others. The simple but profound words ‘our coming was expected on earth’ seem to underline the fact that our own present was previously prepared for us by others, who made it available for us, delivering us our own time in the world, and at a time when we were wholly unknown to them other than as people-to-come. For the purposes of this article it might be seen that this is akin to a constant, un-self-conscious or unwitting act of love, a paternal or maternal act of caring for and safely preserving and delivering the world, its history and its future, for the sake of as yet unknown others.

If Benjamin’s words remain elusive, abstract and esoteric we can also apply them more materially to our museological and archival activities, where we again provide the past with a future and use objects as vehicles by means of which we hope to rescue, retrieve and redeem the past and make it available to a future populated by unknown and unknowable others. If we do not have objects that represent every aspect of early modern experience then we might at least have photographic, cinematographic, or earlier forms of video image that today allow us to peer into the times of our childhood, the lifetimes of our parents, grandparents and great-grandparents, a time when modernity was less advanced and complete and yet perhaps more novel, more imbued with hope, wonder, confidence, belief and adventure than it is today. By means of what Benjamin called ‘mechanically reproduced’ images we can connect with early modernity in different ways than we do with pre-modern and pre-photographic eras.[8] The history of art and of humanity is thus divided into two distinct phases: the photographic and pre-photographic.

The mechanically produced photographic image has evolved, even during this author’s lifetime, into the video image and the digital video image, thus allowing and inviting an exponential increase in the number and accessibility of archived images of the modern past.[9] The digital age, initially so associated with the future, turns out to have an archival quality. Today its identity as a technology of the future has been diverted into the service of attempts to comprehensively record the past in the form of digitised museum collections. Such developments might be seen to extend both André Malraux’s photographic ‘museum without walls’ (1967) and Douglas Crimp’s postmodern theorisation of ‘the museum’s ruins’ (1993) and lead us to a reading of our own epoch as an age of the digital, image-based archive.

Meanwhile, this great increase in the availability of digitally archived images might balance the otherwise disorientingly futuristic, intangible and inhuman qualities and quantities of the digital and data realm. As our digitised archives grow, and as they themselves begin to age under the ever-present threat of being surpassed by yet newer technological processes, so the proximity, prevalence and pathos of the past becomes an increasingly defining aspect of our twenty-first century environment.

Such an increased prevalence of the reproduced past renders the present, by comparison, all the more effervescent, ephemeral and difficult to evaluate. For a society habitually attuned to the fractions of seconds of iPhone scrolling and photographically influenced lifestyles the present is reduced to the finest crest of a constantly breaking temporal wave that nevertheless denotes the foremost limit of an increasingly voluminous past, swollen with archived images and other recordings of passed time and events.

Correspondingly, our future becomes strangely void, a vertiginous no-go zone into which twenty-first century humans peer in vain, a future from which humans feel already excluded, though we might suspect that some kind of future may yet be visible to, or known by the digital itself as a realm of generative code and predictive text, artificial intelligence and the robots currently queuing up to populate it.

However, it is there, it seems, in a digital future apparently uninhabited by humanity, that Elizabeth Price’s digitally contrived image, in K, of a strange stocking-making apparatus, whirrs-on. The machine works away often occupying one screen of her two-channel video, a diptych that balances evocative glimpses of the ‘popular past’[10] (O’Kane, 2019) with this strangely unpopulated vision of the future. The machine works relentlessly, tirelessly, all but effortlessly, with no apparent need for human assistance or interference, even as its purpose is to produce and package articles of clothing apparently intended for living, breathing human bodies.

The written, and robotically enunciated spoken text that accompanies Price’s assembled images refers to an ‘Orphic gloom’ that seems to pervade both the realm occupied by this machine and that from which video clips of 1960s pop singers simultaneously emerge. But this ‘gloom’ might also correspond to the darkened space in which the video K is actually displayed (according to strict installation parameters set by the artist), a particular gloom that extends the subtly shamanic, ritualistic, and hypnotic atmosphere of the video into our real and actual environment. As this ‘gloom’ becomes a central and pervasive reference in the work, relating its content to its mode of display, Price’s compelling rendition of the contemporary possibilities of video art places the audience in a quasi-religious scenario, like worshippers at a darkened shrine, humbled by the magic of an electric beam of light as it produces dancing images that we are invited to decode. Mathilde Roman (referred to above) might then be prompted to consolidate her thesis and concur that the age of video art is an age of hallowed, mysterious, dark, ritualistic, and perhaps even strangely ‘ancient’ spaces that provide a balance to those increasingly bright, modern ‘white cubes’ that typically provide for the contextualisation of much contemporary art (though these are also quasi-religious, or church-like in their own way[11]).

Towards the end of Price’s K, a single stocking is thrown-out by the machine that weaves it, as if the machine were playing now a salesman proffering a sample or a perhaps a stripper enacting a teasing routine. Like the finest of gauntlets this single (virtual, digital) stocking falls before the audience, and in doing so makes a subtle provocation. Its singularity, a lone object that invokes detachment from a pair, calls upon the individual subjectivities that make up the video’s audience, appealing to each of those singularities and thus to our innate fear of disconnection or detachment. The stocking emphasises the empathic quality essential to any fetish, and a single stocking must surely be regarded as a kind of arch, ur, or quintessential modern fetish of the Freudian kind.

If there is any ‘object’ to be ‘loved’ or empathised with here it is, however, neither the individual stocking nor any specific experience associated with it. Rather the individuated fetish of the single, ejected stocking seems to act as a relay for, and to, all of the sensory promise that might be enfolded within the past and all of the past that can be retained in a sensual object. The flourish with which this single, typically fetishistic object is flung before the audience might therefore call upon us to rescue, retrieve, collect and unpack the past anew, and to always do so. If so, then the strange machine weaving away in Price’s K comes to represent the process of history itself, revealing it as a machine that weaves from threads and strands of some mysterious base polymer that may be time itself, various fetishes capable of linking us to passed and lost times and events.

Karl Marx reinterpreted the ancient function of the fetish as having been translated in modernity into commodity form, wherein it exacerbates desire and cultivates the salivations of consumerism (Marx, 1954). Meanwhile, that other guru of modernity, Sigmund Freud implied that fetishism in and for a modern society, morphs from a religious object associated with the magic of shamans and gods into a memorial object whose mystique and power is derived from modernity’s new and crucial relationship to the past, against and by means of which modernity necessarily distinguishes and defines itself (Freud, 1927). Here, the past becomes modernity’s overarching, omnipresent and omnipotent other, and the modern museum supplants temple and shrine to become the tabernacle of history – modernity’s core belief system.[12]

Weaving away in the gloom, Price’s ‘history machine’ suggests an uncanny and inhuman sense of mechanical autonomy, reminiscent of history’s famous ‘spiritualisation’ by Hegel (1975), subsequently materialised by Marx and now perhaps virtualised by theories and theorists of the digital hurriedly preparing for a coming age of artificial intelligence, robots, and self-servicing museums. Indeed it seems possible that before too long museological archives might only rarely, if ever, be seen directly by human eyes, having been roundly rendered by digital photography or photogrammetry, before being housed in remote spaces that are more like those inhabited by huge computer servers that enable museum collections to be seen remotely than the current nineteenth century cathedral-like buildings we visit today in order to see the past contained in an object under glass.

Once thoroughly digitised, a historical object or collection might of course be seen from anywhere in the world and at any time, even virtually handled and examined in detail by experts, tourists and casual internet surfers alike, as well as virtually set and reset in an infinite number of contexts and combinations, rather than established for years within a certain vitrine and/or in a certain juxtaposition with other objects with which it is tied into a particular historical narrative.

The peculiar and particular objects made by Price’s machine are acid green stockings, shown here as highly commodified, brand-new, and provided with crisp packaging that features seductive graphics and the intriguing moniker K (the brand-like title of the artwork itself). These are all seductive devices with which consumers are familiar and which we find it hard to resist. They exacerbate desire, tempting us to obtain, unseal, and thereby claim a commodity as our own. Popularly regarded as an arch image of a certain modern mode of erotic fetishism, sheer stockings of the kind represented by Price mark themselves out today as quintessentially modern, even while consciously and unavoidably referring to an earlier stage of modernity. They may thus be an example of the kind of ‘retro’ or ‘vintage’ object capable of charming and reassuring our own accelerant time by confidently making reference to and valuing its increasingly archived past.

The antique eroticism of the stockinged, gartered and corseted (Georgian, Victorian, Edwardian, etc.) eras of women’s wear and underwear spans the rise of the modern (bourgeois) culture that Sigmund Freud is credited with liberating from its debilitating, unsuitable and anachronistic sexual repression. The persistence of the stocking (despite being surpassed by more modern, functional, newly technologised vogues for various ‘nylons’, ‘tights’, ‘leggings’ and ‘hose’, throughout this dynamic period of changes in fashions and textile technologies) renders it an arch modern fetish that inevitably becomes untimely and uncanny, thereby also taking on the ‘revolutionary’ quality located by Surrealist André Breton in ‘the outmoded’ (as suggested by Walter Benjamin).

… [Breton] was the first to perceive the revolutionary energies that appear in the “outmoded”, in the first iron constructions, the first factory buildings, the earliest photos, the objects that have begun to be extinct, grand pianos, the dresses of five years ago, fashionable restaurants when the vogue has begun to ebb from them. The relation of these things to revolution…

In Price’s video, the classic or vintage stocking not only survives decades or even centuries of modern fashion history but lives on as a fetish into a depopulated digital future gloom, a post-human future place and time of the digital, a crepuscular archival realm that accommodates an increasingly unwieldy and voluminous past, a realm in which all that has been made for and by the human no longer has a human to witness, use, or enjoy it. Thus, any affective pull, or feeling of ‘love’ for objects or images that we might sense while watching Price’s K simultaneously becomes a ‘work of mourning’ as described by philosopher Jacques Derrida (2001), mourning for lost time itself but also for the loss of the direct, real and actual sensual experiences of objects and images that are increasingly ‘lost’ to the voracious futuristic regime of digitisation.

Ultimately our response to Price’s video might then be a form of ‘gloomy’, melancholic resignation that allows us to begin to accept the implications of a post-human future in which ‘history machines’ (in the form perhaps of silo’d digital servers) work away in remote, unnaturally and inhumanly gloomy spaces, contriving and processing virtual fetishes that stand-in for, relay, and signal more tangible forms of ‘object love’ that we might justifiably fear losing, both to the inexorably passage of time and history, and to the exponentially growing realm of the digital. Twenty-first century human culture thus becomes a shrinking candle, burned away at both ends, by past and future alike.

Conclusion

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191209/006In the text that initially motivated much of this process and introduced this project, Geoghegan and Hess implied that artists, curators and museologists today might not just scientifically cater for, organise, record and research the objects with which we deal, but that they (and we) also tend to ‘love’ them. Furthermore, we tend to do so in, perhaps, a new and special way that (as the author’s own writing, and the work of the video artists described above suggests) might be influenced by new technologies of digitisation and virtualisation.

These thoughts have led the author, and hopefully the reader too, along a widening path towards a variety of conclusions, which include the idea that our ‘love’ for such objects invariably involves a connection to, or fetishisation of the irretrievable past itself. We make of the past itself a ‘love object’ that we have lost, then award fetishistic values to objects and images that give us the tantalising sense of reaching for, connecting to, and approximating the past itself.

Mechanical, and then digital reproduction, as played out in our three key examples above and developed in the twenty-first century video art is able to transmit personalised and intimate narratives, expressing affective attributes of artists’ sensual and sentimental experience. Despite video art’s relative intangibility as an art medium it is, I argue, capable of affecting or ‘touching’ audiences with a special sense of empathy, particularly when presented in a contrived space designed to increase its sensual affects.

The three artist’s videos by Carr, Song and Price, discussed here, illustrate various forms of ‘object love’ that video art is capable of transmitting, despite its relative dematerialisation. However, it is, in part, the very intangibility of the medium that skews the ‘objects’ it represents, and thus skews any ‘love’ we might feel for them, in the direction of fetishism.

Museological objects with which we might develop a ‘loving’ relationship retain traces of a past that seems to be thereby ‘contained’ or ‘embodied’. However, in the article above the author has made a separation between any particular object or image of the past and the past itself. This suggests the possibility that we might ‘love’ the past itself, in itself, no matter what atrocities and abominations, and equally beautiful and redemptive events it may contain. We ‘love’ the past itself precisely for the metaphysical or transcendent inaccessibility that places it beyond the limits of human attainability.

Video art, as illustrated above, tends towards the archival. Like museology, it can be seen as an art of collecting, arranging, evaluating, juxtaposing and explicating. Hence, above, we arrived at the statement ‘screen becomes vitrine (or vice versa)’. Meanwhile, the ‘becoming’ referred to here is demonstrated by reference to the comprehensive process of digital imaging currently being undertaken by many contemporary museum collections as they prepare for a digital, virtual, globally accessible future which may significantly change museums and the part that ‘object love’ plays in our relationship with them. Thus our use of the three video artists returns us to Geoghegan and Hess’s original prompt.

While the development and culture of the vitrine, via the historically celebrated ‘wonder cabinet’ seems to symbolically found the modern culture of museology, it may be equally the case that the steady improvement of the glass lens, allied to increasingly modern and sophisticated cameras and projectors, mechanical and then digital reproduction, and the exponential proliferation of ‘screen culture’, brings us to our current ‘age of the archive’[13] (O’Kane, 2019). This is an age where every object is invited to enter into an afterlife initiated by its photographic reproduction and transformation into an image, a disembodied image that can be projected on or through one form of screen or another and made available to online viewers worldwide to scrutinise in ways that wouldn’t be possible or allowed in the realm of real and actual objects.

Ultimately, the method of using three video artists and their works as vehicles by which to expand and explore Geoghegan and Hess’s interest in museological ‘object love’ has led to a revised understanding of the way in which the object, subjected to a history of changing technologies of reproduction and representation, increasingly becomes both image and fetish in an age of increasing virtualisation. While the traditional museum provides a series of vitrined objects that may tantalise us with an embodied sense of connection to the past, the author’s use, in the article above, of video art as an alternative ‘lens’ or episteme through which to explore Geoghegan and Hess’s concept leads to an increased awareness of our age as an ‘age of the archive’ and of a pervasive ‘screen culture’ wherein fetishistic images may just supplant ‘object love’.

The ‘object’ that we ‘love’ thus shifts from being an indexical link connecting us to the otherwise inaccessible past, into being a fetishistic image that reminds us of the true inaccessibility of the past – a slightly ‘gloomier’ thought. However, the past itself, even if it can never be an ‘object’ in the sense of a material presence, is at least an ‘object’ in the sense that it retains the qualities of a trajectory of desire as an unobtainable ‘grail’ that continues to provoke within us a sense of adventure and thus makes of our research a form of quest or romance.

Tags

Footnotes

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text