AIDS memorials from obituaries to artworks – a photo essay

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201403

Keywords

Activism, AIDS memorial, Conservation, Cultural heritage, healing, History of Medicine, Monument, Mourning, Necrology, Online repository, Oral history, Remembrance

Introduction

The first public report of a rare disease among gay men occurred on 18 May 1981 in the New York Native, then the leading gay newspaper in the US, repeating New York City public-health officials’ claims that there was no wave of disease sweeping through the gay community. But only two and a half weeks later, on 5 June, the Center for Disease Control (CDC) published the first clinical report on five incidences of Pneumocystis jirovecii (formerly P. carinii) pneumonia (PCP) in a cluster of injecting drug users and homosexual men, an opportunistic infection which will become one of the AIDS-defining illnesses. The New York Times promoted the term ‘Gay-related Immune Deficiency’ (GRID), while researchers used the term ‘4H disease’ to describe affected heroin users, homosexuals, haemophiliacs and Haitians. The CDC introduced the name Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) on 27 July 1982.

Ever since individuals began to die from the disease, memorials and monuments have been created and this photo essay charts the evolution of these from the 1980s to the present day, showing the variety of forms these have taken from informal, ephemeral and activist orientated endeavours to more formal and institutionalised projects.

Materials and methods

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201403/001The survey is predominantly based on the online repository AIDSmemorial.info/memorialSIDA.info, launched in 2011 by Stichting NAMENproject Nederland with the aim of listing all AIDS memorials worldwide with a name, a photograph and basic information, and documenting the fate of the memorial by the inclusion of actual information from the web in the original language (Stichting NAMENproject Nederland, 2020). The website makes use of the content management system (CMS) Carambola G2.5 v2011, customised by Mikoon Webservices for our needs, designed by Gebr. Silvestri and implemented and hosted by Firma Netjes.

Photos qualify for inclusion in the repository if they show the memorial or parts thereof. They are physically downloaded and stored in the CMS and accompanied by the part of the original text that refers to the memorial. At first, initiators of the memorials were asked to provide an introductory text of no more than 350 words. But because feedback was scarce and sometimes did not include the requested information, the text has been created by amalgamating snippets from the most informative sources. The basic information is provided in seven languages (English, French, Spanish, German, Dutch, Russian and Chinese). Translations are performed using Google Translate and checked afterwards by a native speaker.

AIDSmemorial.info already offers four exclusive categories for filtering: monuments; movable memorials; digital memorials; and ceremonies and symbols. This survey further categorises the large variety of immobile (and mobile) memorials. Categorisation primarily by form turned out to be a workable approach; in some cases categorisation by function has been applied.

The categories

Twenty categories of different size have been identified and are presented more or less in the order of their first appearance.

1. Obituaries and gravestones citing AIDS (1982)

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201403/002

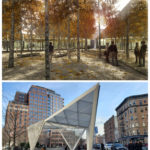

(Left) Obituary for Michael Maletta in the Bay Area Reporter, San Francisco, 12 August 1982, in Searchable Obituary Database

(Right) Memorial slab on the grave of Salvatore Mormone at St Barbara cemetery in Amsterdam, 10 June 2012

© GLBT Historical Society / Wiebe van der WoudeThe Bay Area Reporter, the leading gay newspaper in San Francisco, first named Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS), another AIDS-defining illness, as the cause of death in an obituary for Michael Maletta on 12 August 1982 (see Figure 1 (left)) and AIDS for James R Howell on 11 November in that same year. The obituary for Richard Herbaugh on 23 December 1982 discloses his suicide after diagnosis with Kaposi’s sarcoma and even prints his farewell letter in full. These ‘new style’ obituaries are open about the cause of death, surviving partners, sexual orientation and/or route of infection. Mentioning AIDS can be part of the individual’s last will and community newspapers often provided the only possibility to fulfil it. The GLBT Historical Society of Northern California worked together with the Bay Area Reporter to create a searchable database of all obituaries that have appeared in the Bay Area Reporter since it began publishing them in 1972.

In the Netherlands, the first obituary explicit about AIDS being the cause of death was for Lefert Scheeper, published in the daily newspaper De Volkskrant on 12 January 1985 followed by a very personal obituary in De GAY Krant. In 1990, the newly founded Drug Pastorate Amsterdam started publishing openly written obituaries in their Nieuwsblad, the first for a man named Just (see Digital memorials).

While obituaries naming AIDS inform people that know the deceased in one way or the other, inscriptions on gravestones have a less immediate effect and are mainly directed at random passers-by. Nevertheless, many people wanted to make a statement so that the disease could not be silenced any more. In Amsterdam’s St Barbara cemetery, you can find a very moving inscription on a memorial slab of 1991 (see Figure 1 (right)):

Ik, Salvatore Mormone, overleden door aids wil dat de mensen weten dat ik niemand schuldig acht voor deze ziekte. Ik wil het Koninklijke Huis, met name Hare Majesteit Koningin Beatrix, laten weten dat ik dankbaar ben voor het verkrijgen van de Nederlandse nationaliteit. In Nederland, mijn nieuwe vaderland, heb ik de mooiste jaren doorgebracht. Ik wil te kennen geven dat ik trots ben op de Nederlandse nationaliteit. Getekend, Salvatore Mormone

(I, Salvatore Mormone, died of AIDS and want people to know that I consider nobody guilty for this disease. I want the Royal Family, especially Her Majesty Queen Beatrix, to know that I am grateful for obtaining Dutch nationality. In the Netherlands, my new homeland, I have spent the best years. I want to express that I am proud of my Dutch nationality. Signed, Salvatore Mormone)

2. Annual AIDS memorial and awareness days (1983)

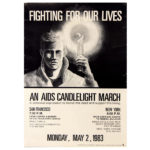

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201403/003

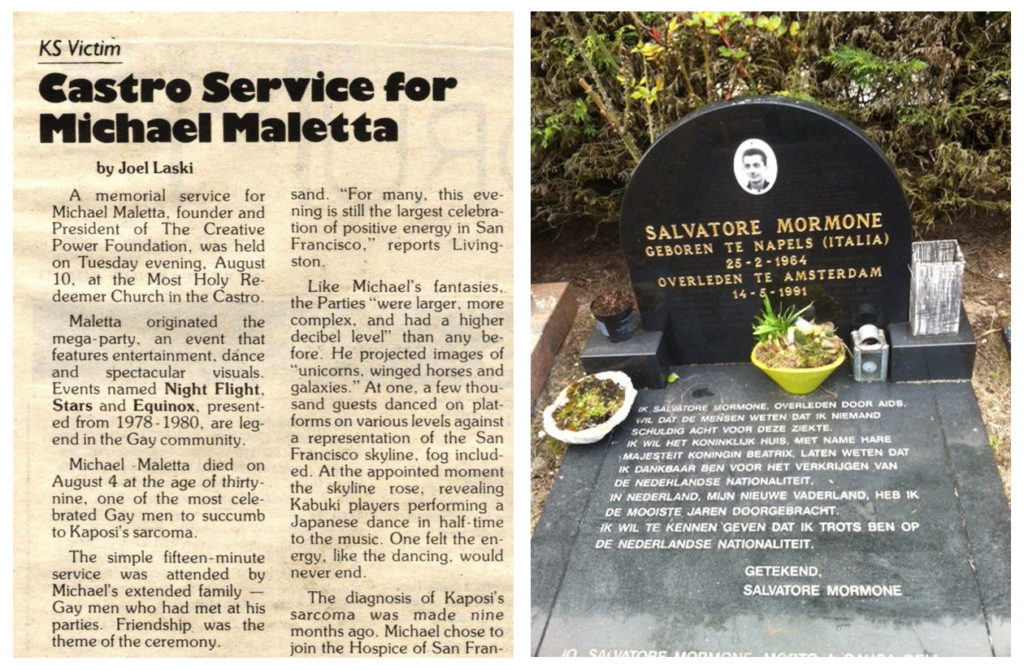

Poster ‘An AIDS Candlelight March’, illustrated by David Emfinger (1983), 66cm x 48cm

© ClampArt, New YorkCandlelight assemblies are held to show support for a specific cause, typically in memory of the dead or to protest the suffering of a group of people. Knowing that they would die within the year and with no political support, four young men – Bobbi Campbell, Bobby Reynolds, Dan Turner and Mark Feldman – coordinated the small vigil ‘Fighting for Our Lives’ on 2 May 1983 in San Francisco and New York, with Boston, Chicago, Dallas, Houston and Los Angeles joining in on the same night. After having founded the organisation Mobilization Against AIDS, the group called it International AIDS Candlelight Memorial, which, since 1985, has been held on the third Sunday in May. The Global Health Council took over the organisation of the event in 2000 until it was transferred back to the source community, the Global Network of People living with HIV (GNP+), in 2011.

When on 1 December 1988 the first World AIDS Day took place, it was predominantly conceived to raise awareness of the disease to the general public. James W Bunn and Thomas Netter of the World Health Organisation (WHO) proposed 1 December, expecting to maximise coverage by western news media – it’s sufficiently long after the US elections but before the Christmas holidays.

In many countries, World AIDS Day has also become the day to remember those who died from the disease, especially in countries that never adopted the Candlelight Memorial in the first place.

On the second World AIDS Day, 1 December 1989, the New York-based group of artists Visual AIDS introduced the Day Without Art, A National Day of Action and Mourning. In response to the devastating effect of AIDS on the arts community, US art and AIDS groups were shutting down museums, sending staff to volunteer at AIDS services, or sponsoring special exhibitions of work about AIDS.

For Day With(out) Art 2020, Visual AIDS presented TRANSMISSIONS, a programme of six new videos considering the impact of HIV and AIDS beyond the United States. The online premiere of TRANSMISSIONS was presented in partnership with Whitney Museum of American Art, The Studio Museum in Harlem, and The Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA), and supported by a large number of museums in the US, Canada, Germany, Greece and Turkey.

3. AIDS books of remembrance (1983)

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201403/004

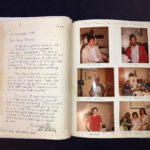

Scrapbooks Volumes 1–11 (series 1), San Francisco General Hospital AIDS Ward 5B/5A Archives, 1983–2003 (SFH 12), San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library, San Francisco, CA

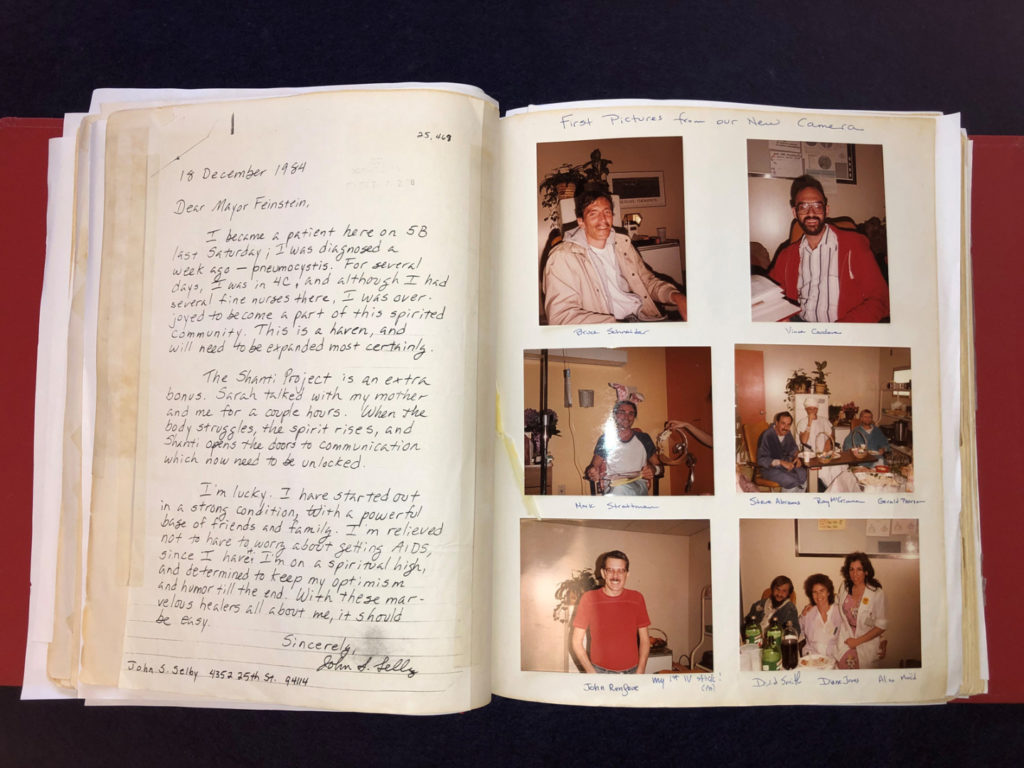

© San Francisco Public LibraryThe first books of remembrance appeared in institutions exclusively dealing with AIDS. When the San Francisco General Hospital opened their interdisciplinary AIDS ward, Ward 5B, on 25 July 1983, they kept a scrapbook documenting important events from the first week onwards (see Figure 3). The first pages of this ‘Red Book’ containing a necrology of people that died in the ward is preserved in the SF History Center of the San Francisco Public Library (San Francisco History Center, 2020).

Similarly, a book of remembrance was created in the newly formed Spellman Services Center of St Clare’s Hospital (later named Spellman Center for HIV-related Diseases) in New York City (Baxter, 1997, pp 1–5). The hospital, situated in a poor part of Manhattan, was the second in the US to specifically care for AIDS patients and opened its doors in November 1985.

While some books are more formally organised as an official registry, others are open to the public to leave their thoughts on a loved one. The Schorer Buddyproject, an HIV-AIDS-specific buddy project in Amsterdam founded in 1984, created a Herdenkingsboek held as a treasure in a glass vitrine, which I could take a look at in their office at Sarphatistraat 33–35 in 2007, five years before they went bankrupt. A large part of their archive is at IHLIA LGBT Heritage but does not include the book of remembrance (Wiedeman, 2020). Because service projects need to promise confidentiality on the identity of their clients, people speculate that it is still in private hands (Holweg, 2020). A similar scrapbook displayed in a spiritual corner of the Hiv Vereniging at Eerste Helmersstraat 17, which I was also able to browse through, remains untraceable after the corner was dismantled (Brokx, 2020; Mielitz, 2020).

The Church of St John the Baptist Timberhill in Norwich, England, still uses their AIDS Book of Remembrance inaugurated in 1993 in the annual World AIDS Day service. The Ecumenical AIDS Initiative Kirche PositHIV (Church PositHIVe) in Berlin had displayed an AIDS-Gedenkbuch since 1993 until their termination at the end of 2019, based on a ‘London example’ as they write. The New Zealand Book of Remembrance was launched at the AIDS Candlelight Memorial and Beacons of Hope ceremony in Auckland (1994), dedicated at St Matthews-in-the-City (1995), and permanently displayed in a specifically designed cabinet since 1996.

4. AIDS chapels and other memorials in churches (1985)

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201403/005

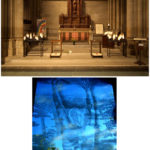

(Top): National AIDS Memorial at Cathedral St John the Divine in New York, 12 September 2004

(Bottom): AIDS Memorial Chapel of the Damien Brothers in Albuquerque transformed into a spiritual bookshop, date unknown

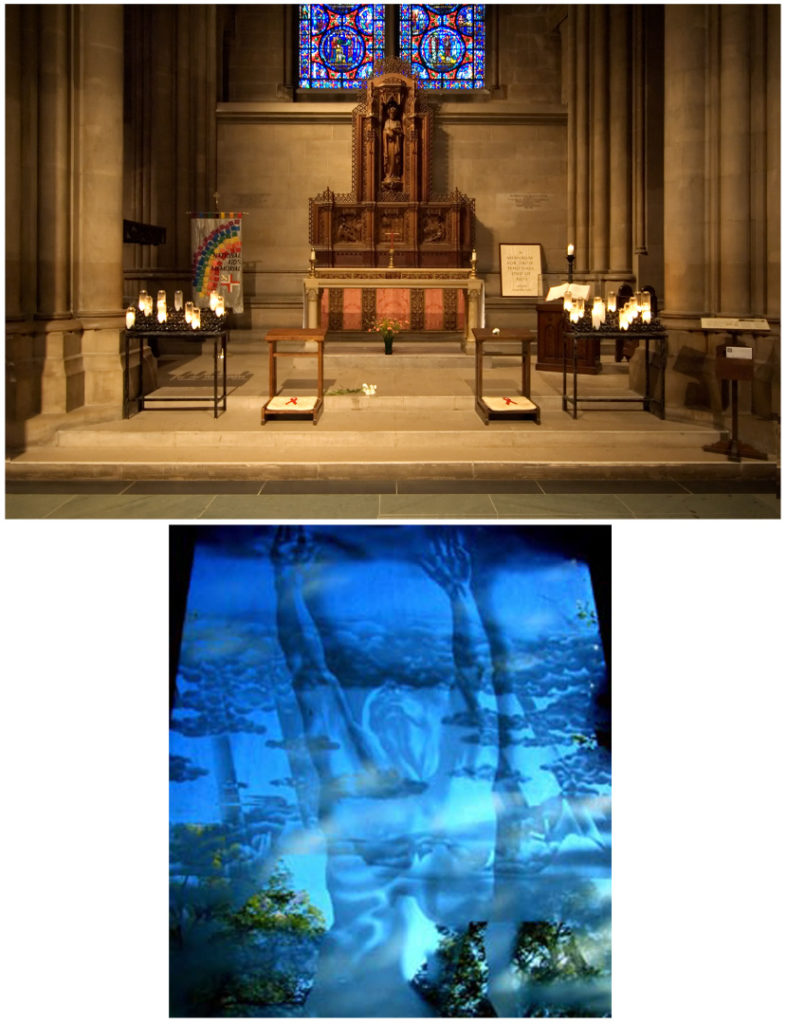

© Graham Lyth / Center for Action and ContemplationDedication of church chapels to a specific group of people has a long tradition, and many have a chapel dedicated to the sick. The Cathedral Church of St John the Divine in Upper Manhattan, New York, was the first to create a place to commemorate people lost to AIDS. Known as ‘The National AIDS Memorial’, it is situated in its medical bay and was inaugurated on 9 November 1985 (see Figure 4 (top)). It consists of the AIDS Memorial Book containing the names of people who have died from complications of AIDS, and the AIDS Memorial Banner, which features an outline of the cathedral tower, plus patches in the form of a rainbow and the lambda sign – both symbols of the LGBT community – added to the seal of the Episcopal Diocese.[1]

The triptych The Life of Christ by the artist Keith Haring installed on 26 June 1994 in the Chapel of St Columba is the actual attraction of St John the Divine but not associated with the National AIDS Memorial. A year later, another cast of Haring’s triptych was made the centrepiece of the newly designated AIDS Chapel in Grace Cathedral, San Francisco (1995). Furnished with symbols of world faiths, a book of remembrance with nearly five hundred names and two periodically changed blocks of the AIDS Memorial Quilt hanging from the vaulting, it was inaugurated as AIDS Interfaith Memorial Chapel in 2000 and refurbished in 2017.

AIDS memorial chapels have also been designated at St Thomas the Apostle in Hollywood (1989), Southwark Cathedral in London (1991), St Victor’s Catholic Church in West Hollywood (1994), and at the Church of the Redeemer in Morristown, New Jersey (1995). The Damien Brothers created an AIDS memorial chapel on their grounds in Albuquerque, New Mexico in the 1990s. In 2001, they sold the property to the Center for Action and Contemplation, which transformed the chapel into a spiritual bookshop leaving the etched glass window untouched (see Figure 4 (bottom)).

The Church of St Veronica on Christopher Street in New York created their AIDS memorial in 1991 by drilling plaques with the names of men who died from the disease into the choir loft. An AIDS memorial bell with names of the deceased has been installed at St James’ Church in Sydney (2003), and in 2017 the Trinity United Methodist Church in Kansas City, Missouri, created an AIDS memorial in the form of a cuboid sticking out of the ground and bearing a plaque.

Surprisingly, only the Episcopal and Methodist parishes (all in the US) mention their AIDS memorials on their websites (St Thomas the Apostle, 2020; Church of the Redeemer, 2020; Grace Cathedral, 2020; Trinity United Methodist Church, 2020). St John the Divine mentions its chapel only on their archival pages (The Archives of the Episcopal Church, 2020).

5. AIDS memorial trees (1985)

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201403/006

First known AIDS memorial (Cherry Tree Grove) at Devonian Harbour Park, Vancouver, April 2013

© AIDS VancouverThe tree of life is a fundamental archetype in many of the world’s mythologies and religious traditions, often relating to immortality. On 20 October 1985, the organisation AIDS Vancouver planted four cherry trees in the Devonian Harbour Park in memory of four men who died that year and whose first names only were disclosed: James, Ivan, Gino and Randy. Without a plaque and to protect the trees from vandalism, attendees were asked not to reveal the trees’ exact location. As an unwanted side-effect, the Cherry Tree AIDS Memorial Grove fell into oblivion until the site was rediscovered in 2012. A young tree was planted for the fourth tree, which had gone missing, and on 4 September 2018 the grove was rededicated with a plaque on a large boulder as the ‘First Known AIDS Memorial’ – the original planting took place exactly twenty days before the dedication of the AIDS chapel in St John the Divine in New York.

Since 1989, personalised AIDS memorial tree plantings followed in Toronto’s Cawthra Square Park (now Barbara Hall Park), years before the idea of a solid memorial was implemented, and even continuing afterwards.

General AIDS memorial trees have been planted at a different location in Toronto (1989, not far from the Legislative Assembly on behalf of the Province of Ontario), in Cairns (1990), Auckland (1991), Manchester (1993) and Newcastle, Australia (2008). Trees of life to commemorate the Tainted Blood Tragedy of Canada have been planted at 17 locations all over the country (2007–2016).[2]

6. AIDS memorial gardens and groves (1986)

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201403/007

Garden of Peace and Love in Laguna Beach, California, 15 November 2014

© Don Leach, Daily Pilot, Los Angeles TimesUnlike memorial trees, memorial gardens can be a means of coping with bereavement through physical work among like-minded people. Early AIDS memorial gardens emerged informally on unused land. In 1986, Michael Lee created a Texas Memorial for AIDS victims on abandoned railroad land behind his house in suburban Houston, which only gained visibility in 2013 after a bike trail passed through it. In Laguna Beach, California, Michel Martenay created the Garden of Peace and Love in 1989 at the stairs that access the beach near the legendary gay bar Boom Boom Room (see Figure 6). In 1990, Dallas Tavern Guild members planted 1,800 daffodils in Lee Park — one for each person in Dallas County who had died of AIDS. It was 1992 before a plaque containing the word ‘AIDS’ was allowed to be installed.

The first officially established AIDS memorial gardens arose in 1988, near health care institutions for the use of patients and their families, particularly those with HIV: outside Fairfield Hospital in Melbourne and in the courtyard of London Lighthouse. In the meantime, both institutions closed, Fairfield in 1996 and London Lighthouse in 2015 – but their AIDS memorial gardens have been preserved. Most AIDS gardens that followed were created within an existing park and designed as places for contemplation and healing.

National AIDS Memorial Grove Circle of Friends, December 2016

© National AIDS Memorial https://aidsmemorial.org/A professional approach was chosen for what would become the AIDS Memorial Grove in San Francisco after a steering committee selected the long-neglected de Laveaga Dell in Golden Gate Park. Ground breaking with the mayor had taken place in September 1991; a team of 22 landscape architects and designers volunteered to develop a basic design and master plan. A full-time city gardener started working in July 1995 and on World AIDS Day that year a granite boulder inscribed with the Grove sign was placed at the entrance terrace of the ‘Main Portal’. In February 1996, the ‘Circle of Friends’ feature was added (see AIDS monuments of names) and in October 1996, US Congress designated the AIDS Memorial Grove as a National Memorial. What initiators Isabel Wade and Nancy McNally envisioned as ‘a beautiful grove where people could find solitude and hope while remembering loved ones’ (Wikipedia, 2020) has turned into a ‘healing landscape’ (Heyman, 1998). But the Grove remains a work in progress, and various features have been added in the meantime.

The people in San Francisco were more fortunate: they could chose an area which already contained old trees. Other gardens were started from scratch, such as in Lahav, Israel (1993), Sydney (1994), Denver (2000), Canberra (2017), or the Birchgrove Memorial Grove for people affected by contaminated blood or blood products in Swindon, England (1996).

L’Artère – Le Jardin des Dessins in Parc de la Villette, August 2009, arial view

© Fabrice HyberFabrice Hyber went a totally different way when Sidaction asked him to design an AIDS memorial garden for Parc de la Villette in Paris, a new park with the aim of supporting activity and openness to life. Within its wefts, Fabrice Hyber created L’Artère – Le Jardin des Dessins (The Artery – Garden of Drawings) in 2006, as ‘a place of life, remembrance and knowledge’, an ‘anti-monument’ where ‘it is forbidden to die’ (Hyber, 2009). His drawings touch on topics such as fear, transmission routes, condoms, love, gender identities, immune system, religion and death in a symbolic way (see Figure 8).

7. Symbols of AIDS awareness and solidarity (1987)

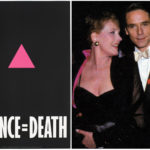

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201403/008

(Left): Original 'Silence=Death' poster

(Right) Red Ribbon first worn publicly by Jeremy Irons co-hosting the 45th annual Tony Awards, 2 June 1991

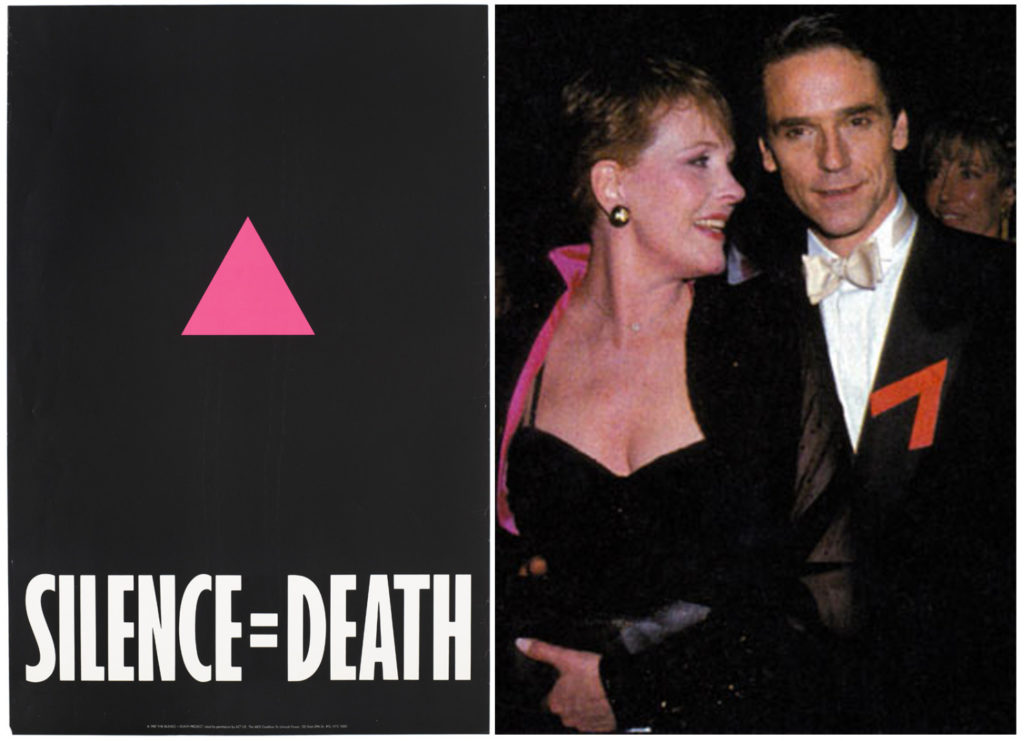

© ACT UP / Visual AIDSIn December 1986, an anonymous collective of six people finalised the design of a poster to combat institutional silence surrounding homophobia and HIV/AIDS. Using abstract language SILENCE=DEATH and featuring a pink triangle (upside down) as a reference to Nazi prosecution of LGBTQ+ people, their work was fly-posted in February 1987 all over Manhattan (Liclair, 2015). After the newly formed AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) had adopted the design in March, placards with the SILENCE=DEATH poster had their first media coverage in ACT UP’s action at the New York City General Post Office where an audience of people was filing last minute tax returns on the night of 15 April 1987 (Crimp and Rolston, 1990).

While the SILENCE=DEATH poster was a perfect means to mobilise people, especially gay people, it was not suited to reduce stigma in the general population.

In April 1991, another anonymous group of people, part of Visual AIDS, came together to create a meaningful symbol to show support and ‘compassion for those with AIDS and their caregivers; and support for education and research leading to effective treatments, vaccines, or a cure’ (Visual AIDS: The Red Ribbon Project, 2020), see Figure 9 (right)). Inspired by the yellow ribbon widely used to support US troops during the Gulf War 1990–1991, the colour red was chosen for its connection to blood and the idea of passion and love. The Red Ribbon was widely adopted at the presentation of the 45th annual Tony Awards on 2 June 1991 in New York. By wearing the ribbon, celebrities, musicians, athletes, artists and politicians have considerably contributed to making it the global symbol of AIDS awareness and solidarity as well as fundraising. The Red Ribbon came to Europe on Easter Sunday 1992 when more than 100,000 ribbons were distributed at the Freddie Mercury Tribute Concert, held at London’s Wembley Stadium.

In 2015, the Red Ribbon became part of the permanent collection at the Museum of Modern Art.

8. The AIDS memorial quilt (1987)

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201403/009

(Top): AIDS Memorial Quilt inaugural display on the National Mall in Washington, DC, 11 October 1987

(Bottom): Quilt blocks from all over world displayed at the Beurs van Berlage during the International AIDS Conference 1992 in Amsterdam

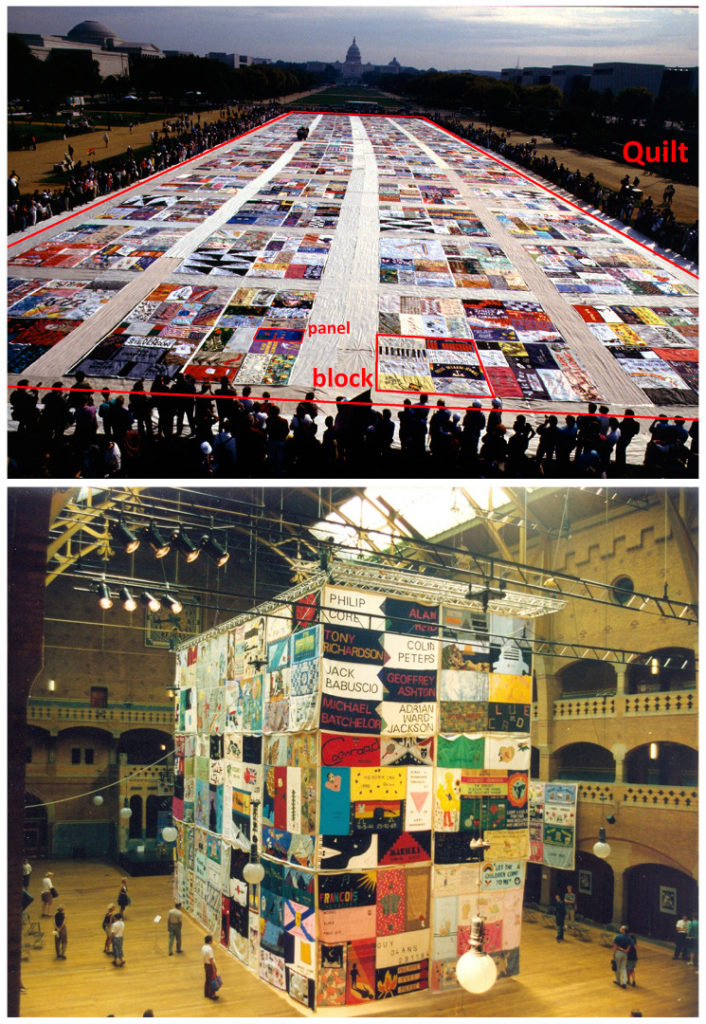

© Smithsonian Open Access / Stichting NAMENproject NederlandDuring a candlelight march in memory of the politicians and activists Harvey Milk and George Moscone in November 1985, Cleve Jones conceived the AIDS Memorial Quilt. The first panel was created in memory of his friend Marvin Feldman and measured 0.90m by 1.80m. Jones teamed up with Mike Smith and several others to formally organise the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt. During the Lesbian and Gay Pride Parade in June 1987, they hung their quilts from the mayor’s balcony at San Francisco City Hall. People sent panels to San Francisco where eight of them were joined to form a block measuring 3.80m by 3.80m (Jones and Dawson, 2000).

During the Second National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights on 11 October 1987 both ACT UP and the AIDS Memorial Quilt made their debut to a national public. While people were shouting “ACT UP! Fight back! Fight AIDS” on the march, the quilt was displayed on the National Mall: 240 blocks were unfolded in a lotus ceremony, the names read aloud. (For the lotus unfolding, the quilt block is folded by putting each corner tip to the centre until a small bundle is left. Unfolding the reverse way results in the tips of the square residing between the previous tips like the opening of a lotus flower.)

Afterwards, several ACT UP groups were founded throughout the USA. The quilt blocks toured the country and new quilting bees made the project grow (Ruskin, 1988).

The quilt idea spread around the globe and projects started in more than forty countries. During the 8th International AIDS Conference 1992 – which had been moved from Boston to Amsterdam due to the uncertain US travel policy toward HIV-positive individuals – quilt blocks from all over the world were slowly hoisted on to a metal frame within the Beurs van Berlage convention centre. While the quilt is the most recognisable symbol of the epidemic, US media accounts of displays and the negligence of the Reagan and Bush administration made it a political failure. It wasn’t until 1996 that President Bill Clinton and his wife Hillary walked among the panels, at a time when combinational therapy was seeing its first successes and the number of new panels had already declined (Pearson, 2011, pp 270–274).

Quilt blocks are now on permanent display at Grace Cathedral in San Francisco and St George’s Cathedral in Cape Town.

9. Wish trees (1991)

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201403/010

Parc de l'Espoir (Park of Hope) on rue Sainte Catherine and rue Panet, Montréal, May 2011

© Société La Mémoire vivante du Parc de l'EspoirOn 1 December 1991, ACT UP Montreal ended its World AIDS Day demonstration in an empty lot in the heart of the district inhabited by people most affected by the AIDS epidemic: gay men, IV drug users and sex workers. The activists hung 1,200 black ribbons in the trees corresponding to the cumulative number of AIDS deaths in Quebec, but the City of Montreal removed the ribbons immediately. In January 1992, ACT UP redecorated the trees with 1,200 multi-coloured ribbons. Thousands of people followed hanging memorial ribbons with names of deceased people, teddy bears and personal objects, and the Aaron Funeral Home used them to drop off the flowers and ribbons left after funerals. In May, an unofficial sign reading ‘Memorial Park for people that died of AIDS in Quebec’ was installed (Metcalfe, 2002).

In September 1994, the park was officially designated as Parc de l’Espoir (Park of Hope). In 1997, the City of Montreal redeveloped the park as a cenotaph, the front section representing death symbolised by black granite blocks with the ribbons bound to flagpoles, the rear with trees reflecting life.

During the summer of 2020, Parc de l’Espoir has been redeveloped and enlarged by integrating the adjacent side street and part of the parking spaces on Rue Cathérine.

Wish trees or wishing trees have a long tradition in many cultures. People identify trees as having some spiritual value and make votive offerings – objects deposited without the intention of recovery or use – in hopes of having a wish granted or a prayer answered. Modern trees can be real or artificial, and people make offerings by hanging trinkets, colourful ribbons and fabrics, or writing wishes on small pieces of paper and hanging these from the tree.

Food For Thought Food Bank in Forestville, California, was founded in 1988 with the mission of providing comprehensive nutrition to people affected by HIV/AIDS. Within its Therapeutic Garden Program, artist Mark Brudzinski created an AIDS memorial in 2010, among others bearing copper ‘leaves’ with names and wishes attached to spiralling metal lianas.

10. Figurative AIDS memorials (1992)

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201403/011The first figurative AIDS memorial was commissioned by the Columbus AIDS Task Force to Alfred Tibor for the Ameriflora exhibition in April 1992. Tibor’s sculpture ‘Reach Out’ shows two open hands sticking out of the ground and ‘represents the desperation felt by so many AIDS victims and that it is asking for help for those battling HIV/AIDS’.

Two crossed hands forming a Red Ribbon by sculptor Guy R Grey make the centrepiece of the Indiana AIDS memorial on Crown Hill Cemetery in Indianapolis (2000).

The Wall of Remembrance in Galveston created by T J Dixon and James Nelson is accompanied with a bronze figure representing human grief (2006). The figure is hollow to represent the emptiness one feels, and is bandaged. It stands humbled with head bowed before the Wall.

Brighton and Hove AIDS Memorial ‘TAY’, 25 August 2010

© Dominic AlvesThe Brighton and Hove AIDS memorial (2009) depicts two intertwined figures, one male figure and one genderless figure that soar up towards the sky (see Figure 12). Shaped into a Red Ribbon, Romany Mark Bruce called his sculpture ‘TAY’ in memory of his best friend, Paul Tay.

11. AIDS monuments of names (1992)

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201403/012

Namen und Steine installation ‘Windrose II’ in front of Dreieinigkeitskirche St Georg in Hamburg, decorated with flowers on the occasion of the monthly AIDS service, 26 August 2018

© Jörn WoltersWhile the AIDS Memorial Quilt or parts thereof are usually only shown for a short time, people at many locations around the globe felt the need for a permanent place to honour a loved one by name and which can be accessed any time.

Namen und Steine (Names and Stones) is a joint project by the artist Tom Fecht and the German AIDS Foundation containing two components. The first component consisted of 250 stones carrying the names of well-known people that died from AIDS, which were laid in the pavement at Museum Fridericianum, Kassel, during the art event Documenta IX on 2 June 1992. At the end of Documenta IX, 75 stones were removed to become part of exhibitions throughout Europe as Memoire Nomade (Heide and Kamper, 2001). Local AIDS organisations in Germany added names in their city (see Figure 13), and when Tom Fecht ended his involvement in the project in 2000, more than 2,300 name-bearing stones had been installed at 24 locations in Germany as well as in Zürich and Riga. Out of the 26 locations, ten have been realised in front of or near churches and eight in front of museums. The project shares a similar concept as Stolpersteine (Stumbling Blocks) by the artist Gunter Demnig, which was initiated later that year to commemorate people who fell victim to Nazi terror. Names in paving stones have also been realised as part of the New Orleans AIDS memorial (2008, see Memorials celebrating survivors).

Toronto AIDS memorial at Barbara Hall Park, 28 September 2012

© Jörn WoltersMichael Lynch conceived the idea for an AIDS memorial in Toronto when he participated in the March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights, seeing the display of the Quilt as well as the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. On Lesbian and Gay Pride Day 1988 a temporary memorial in Cawthra Square Park (now Barbara Hall Park) displayed around two hundred names of those who had died as a result of AIDS. In 1991, the architect Patrick Fahn won the design competition for a permanent memorial with a series of art deco inspired triangular columns, which hold simple plates with engraved names that can be easily updated (see Figure 14). The Toronto AIDS memorial was inaugurated in Lesbian and Gay Pride Week in June 1993 and now displays more than 2,700 names.

There are more ways to display names: West Hollywood decided on bronze plaques in the sidewalk (1993), Key West chose inscriptions in black granite on the entry to a pier (1997), Johannesburg picked bronze plaques on a wall (1998, see also Neglect, vandalism and loss), and Vancouver chose an undulating wall made of iron (2004), to name just a few.

In 1996, a new feature was added to the AIDS Memorial Grove in San Francisco: the Circle of Friends. Engraved names intermingle ‘donors to the grove’, ‘those who have died’, and ‘those who loved them’, an approach that shifts the attention away from the object of mourning.

In 1997, the board controversially discussed additional ‘naming opportunities’ for fundraising purposes. Opponents to the idea felt that prominently featuring additional donor names would erode the inclusiveness of the Grove, but at the end the concerns were overruled (Shibley, Axelrod, Farbstein and Wener, 2000). A similar attempt to allow sponsor logos on the Stele gegen das Vergessen in Berlin resulted in public resentment (Schock, 2011) and was subsequently covered up. Others like the Indiana AIDS memorial created clearly separated entities for ‘Friends, Family and Those Who Care’ (The AIDS Foundation of Greater Indianapolis, 2020). A further Circle of Friends has only been created in Auckland in 2001.

While inscription of a granite stone for the New Orleans AIDS memorial costs $75, and for the Namen und Steine installation in Hamburg €200 ($235), the Grove charges $1,000 for inclusion in the Circle of Friends in the Grove. It remains a challenge to be inclusive of people with low income and hardly any lobbying power.

12. Collective grounds for remains as AIDS memorials (1992)

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201403/013

Wat Phrabat NamPhu AIDS Memorial in Lopburi, Thailand, 1 February 2012

© Huub BeckersThe Wat Phrabat NamPhu AIDS Memorial more or less created itself. According to Thai custom, the AIDS hospice near Lopburi, founded in 1992, cremated the deceased and crushed the remaining bones into powder, which was put into small bags and sent to their families. However, most families rejected them and returned them to the hospice. These bags were then respectfully placed in the meditation room (see Figure 15).

The Loretto AIDS Memorial Garden in Nerinx, Kentucky, originated from the frustration of finding an appropriate place for ashes in St Louis (1995). People with HIV who want to be buried close to their companions instead of in the family tomb can do so in Hamburg (Memento, 1995), Berlin (Denk mal positHIV, 2003), and Frankfurt (collective tomb, 2008).

13. Memorial Dress (1993)

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201403/014

Patina du Prey’s Memorial Dress, video still at minute 4 of ‘Introducing Kiss My Genders’ at the Hayward Gallery, 11 July 2019

Video: https://youtu.be/1NFcSSLXMuU?list=RDCMUCvS2UqiC4p3sLoJCyzIYgNQ&t=4

© Southbank CentreThe Memorial Dress was created and first exhibited in 1993 at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston, where for two months Hunter Reynolds (as his alter ego Patina du Prey) performed daily wearing the dress. During this and subsequent exhibitions in Berlin, Hagen (Germany), and during the 25th anniversary of Stonewall in 1994, people were asked to submit names to a memorial book. By 1996, over five thousand collected names were added to a new second dress, which was again exhibited in Boston as part of the Visual AIDS Archive Project. By 2007, the memorial books contained over 25,000 names. In summer 2019, Patina du Prey’s Memorial Dress was shown at Kiss my Genders, a group exhibition of twenty artists at the Hayward Gallery, Southwark Centre, London (see Figure 16).

14. Digital memorials (1994)

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201403/015The first digital memorial started as a list compiled as part of the exhibition Stonewall and Beyond at Columbia University Libraries, which opened on 25 May 1994. The names of the CU AIDS Memorial have been identified in obituaries, articles and by friends, and amounts to 130 (as of 2015).

The Alliance for the Arts initiated the Estate Project for Artists with AIDS in 1991 to preserve artworks and create archives comprising visual artworks, films, videos, musical scores, dances and manuscripts. In 2003, they launched the National Registry of Artists with AIDS, simultaneously creating a memorial to artists lost to AIDS and a gateway to an important cultural expression. The website disappeared at some point in the 2010s. The Archive Project, a similar initiative by Visual AIDS but restricting itself to visual arts, was founded in 1994 and launched online as the Artist+ Registry in 2012 (Visual AIDS, 2020).

In 2007, Stichting NAMENproject Nederland (NAMES Project Netherlands Foundation) launched AIDSmemorial.nl, an attempt to unite and evolve various initiatives of remembrance. It contains the Dutch AIDS Memorial Quilt with its names and original biographies and the In Memoriam published online by the Hiv Vereniging (Hiv Association). Volunteers scanned all periodicals stored at IHLIA LGBT Heritage and the Drugs Pastorate Amsterdam for obituaries and other stories of people who died from AIDS. Assuming that this material will be digitised in the future anyway, the selected texts have been scanned and converted with the help of staff from gay dating site Planet Romeo. This approach ensured that the text is searchable on the internet but allowed the option of leaving out information that is private and sensitive. The website invited people to submit photos and stories about people under the header Het Leven in Beeld (A Life in Pictures). A third strand of the project gathered legacies, mainly photos of artwork and cover texts of literature by people who have died from AIDS. Since 2017, AIDSmemorial.nl has been integrated into the website of the new HIV/AIDS monument unveiled the year before (see Uncategorised memorials). As of 9 November 2020, it contains the names of 833 people, about 17 per cent of all the people who died of AIDS in the Netherlands.

In 2016, a guy named Stuart who lives in Scotland started the English-language AIDS MEMORIAL on Instagram.

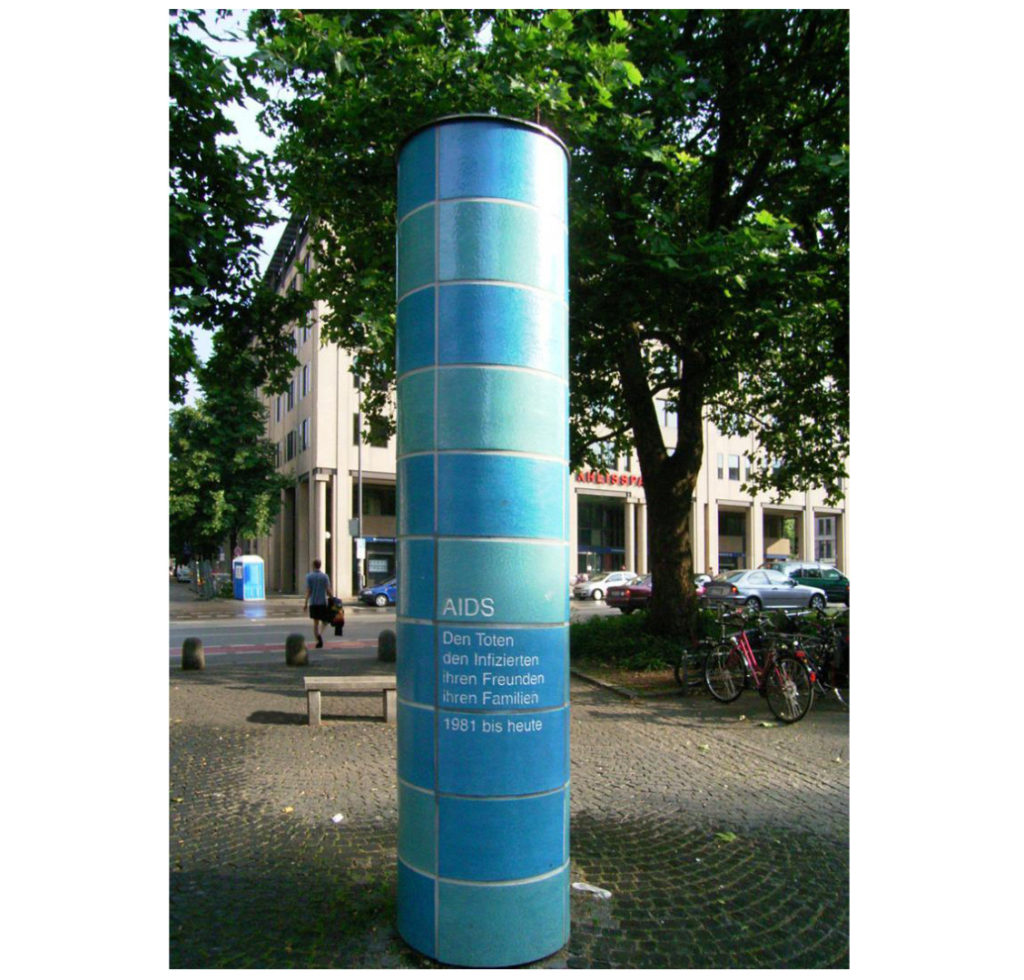

15. AIDS memorial steles (1994)

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201403/016Steles or upright stone slabs are an ancient means to mark important events or territory. The first AIDS memorial in the form of a stele was realised in Cologne (1994), a classical stele matching the church stones behind. The inscription is a haiku by poetess Gitta Benasseni:

Auch das Feuer seht,

nicht nur das fallende Laub,

wenn der Sommer geht(See the fire too,

not just the falling leaves

when summer passes)

‘Beacon of Hope’ in Sackville Gardens, Manchester

© Matt Bramford for Pride ManchesterIn the new millennium, modern versions of a stele appeared in Manchester and Munich. Competition winners Warren Chapman and Jess Byrne-Daniels designed the ‘Beacon of Hope’ light sculpture as a spiralling stainless steel column rising from a mosaic plinth (see Figure 17). Erected in 2000 in Sackville Gardens in Manchester and clearly visible from the Canal Street gay bars, the engraved and pierced hearts on the column gesture towards loved ones lost to HIV and AIDS, and to the compassion needed to help control the disease. Within the plinth, a time capsule has been placed which contains messages to loved ones affected by HIV and AIDS. These can be updated annually as part of ceremonies associated with World AIDS Day. The design also consists of three plinths providing a link to the existing ‘Tree of Life’ planted on World AIDS Day 1993.

'AIDS Memorial München' at Sendlinger Tor by Wolfgang Tillmans, 16 July 2005

© GreenapplePhotographer Wolfgang Tillmans, who won the international design competition in Munich, re-created one of the blue tiled columns of Sendlinger Tor subway station and placed it outside on Sendlinger Tor Square (see Figure 18). “With the AIDS Memorial by Wolfgang Tillmans, Munich moves the topic of AIDS from the underground and places it in the middle of the city,” initiator Thomas Niederbühl said. The inscription in the tiles is short and unsentimental, with a minor detail that friends come before family.

AIDS

Den Toten

den Infizierten

ihren Freunden

ihren Familien

1981 bis heute(AIDS

To the dead

to the infected

their friends

their families

1981 till today)

The ‘AIDS Memorial München’ on Sendlinger Tor Square, a much frequented business area and gateway to the gay and lesbian neighbourhood, was inaugurated on 17 July 2002.

Steles have also been placed as part of AIDS memorial gardens or groves, such as, among others, a colourful monolith by the Senegalese artist Mohamadou Ndoye, alias Douts, in the Bosque de la Memoria (Memorial Grove) in Gijon (2010).

16. Memorials celebrating survivors (1997)

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201403/017A year after the introduction of the combination therapy or highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART), the affected communities in San Francisco felt their positive effect. Flagging in the Park (FITP), which was started in 1997 by Jeff Kennedy, takes place in the National AIDS Memorial Grove in Golden Gate Park. The event is a celebration of life, with a live DJ, a time for reflection, and fundraising for charity. Flags, mostly made of silk, are usually dyed in vibrant, fluorescent colours, creating an almost hypnotic spectacle when spun rhythmically.[3]

In 2004, architect David Angelo and public artist Robin Brailsford combined a serene park setting with a catalyst for change in low-income and hard-to-reach communities of Los Angeles. The Wall Las Memorias’ in Lincoln Park not only consists of two granite panels that contain the names of individuals who have died from AIDS but also six murals depicting life with AIDS in the Latino community.

(Top): ‘Survivor’s Knot’ on the last block of Broadway at River Street in Troy, New York, 22 August 2004

(Bottom): New Orleans AIDS memorial, close view of faces cast in glass, 5 June 2013

© Steed Taylor www.steedtaylor.com / Andrew Belonsky for Out.comThe same year, Steed Taylor went a step further. Over the years, more people with HIV and AIDS lived longer but were still not seen as survivors. The artist decided to honour the resilience and perseverance of AIDS survivors like himself, by doing a series of public artworks called ‘Survivor’s Knots’. In a continuation of his road tattoos, he created (among other works) a Celtic design on 22 August 2004 in Troy, New York, sponsored by the Arts Center of the Capital Region (see Figure 19 (top)). Twelve names of local long-term AIDS survivors and their number of years surviving were painted in the piece. After blessings and well wishes, the information was painted over using the same black latex. Traffic and weather conditions have dissolved it, so I could not detect any remnants when visiting in September 2012.

In New Orleans, survivors even have a face: 34 discs depict the cast faces of individuals, some of whom live with HIV. Artist Tim Tate, who was diagnosed as HIV positive himself in 1989, called his winning design ‘Guardian Wall’. The 34 faces guard those whose names are engraved into paving stones below, people who have died from AIDS as well as people honoured for their efforts in fighting the disease (see Figure 19 (bottom)). The New Orleans AIDS memorial was inaugurated on 30 November 2008 in Washington Square Park, very much the early epicentre of the AIDS epidemic in Louisiana.

17. AIDS monuments in the form of a Red Ribbon (1997)

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201403/018

Hong Kong AIDS ‘Ribbon’ at Kowloon Park, 15 January 2008

© Jimmy EgglestonThe Red Ribbon has been integrated quickly into AIDS memorials, first seen 1992 in the form of a flower bed (Columbus, Ohio) and a path (Buffalo, New York). In the course of World AIDS Day on 1 December 1997, a twin-ribbon bronze sculpture was erected in the Wan Chai commercial district on Hong Kong Island. The sculpture ‘Ribbon’, created by Van Lau, was later moved opposite the entrance of the Health Education Exhibition and Resource Centre at the edge of Kowloon Park.

On the occasion of the 13th International AIDS Conference in Durban in July 2000, a giant Red Ribbon sculpture was added to the mosaic sculpture in Central Park visualising its theme ‘Breaking the Silence’. On World AIDS Day later that year, the park was renamed to Gugu Dlamini Park (see Naming locations after PLWH heroes).

Ribbons subtly integrated in the design of memorials can be detected in Indianapolis (two crossed hands, 2000), and Brighton and Hove (two intertwined figures, 2009), as discussed here under Figurative AIDS memorials. The most inconspicuous AIDS memorial most probably is a pierced ribbon in a railing post on the Uzh River in Uzhhorod, Ukraine, created in 2015.

18. Naming locations after PLWH heroes (2000)

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201403/019Gugu Dlamini comes to mind first when looking for ‘people living with HIV’ (PLWH) that have been permanently honoured for their contribution to fighting AIDS. As part of a campaign of acceptance and disclosure she revealed her HIV status in 1998, firstly on Zulu language radio and later in a packed stadium in KwaMashu north of Durban. Days later, several local men attacked her, harassed her, followed her home and stoned and stabbed her to death. Central Park in Durban was renamed ‘Gugu Dlamini Park’ on World AIDS Day 2000, the actual memorial is the ‘Wall of Hope’ designed by Jeremy Wafer and Georgia Sarkin and situated to the northeast of the Red Ribbon.

Xolani Nkosi was a boy born HIV-positive and when his mother became unable to care for him, he was legally adopted by Gail Johnson. When in 1997 a primary school in the Johannesburg suburb of Melville refused to accept him as a pupil because of his HIV-positive status, the incident caught public attention. Nkosi spoke at the 13th International AIDS Conference in Durban (2000), and died one year later at the age of 12. The Johnson Nkosi Memorial Primary School in Lukojjo, Uganda (date unknown) and the Nkosi Johnson House, a student residence at Stellenbosch University (25 May 2018) are named in his honour.

A decade earlier, Ryan White had a similar experience to Nkosi. A haemophiliac, he contracted HIV through blood products. The middle school outside his hometown Kokoma, Indiana, did not want him to return to school after discovering his illness. The family finally moved to Cicero, where a high school welcomed him. Ryan White died in 1990 at the age of 18. Shortly after his death, US Congress passed the Ryan White CARE Act, a federally funded programme for people living with HIV/AIDS which remains an active piece of legislation today. A State Historical Marker in front of his school in Hamilton Heights, Indiana was unveiled on 30 August 2019.

Promenade Cleews Vellay in Paris, street sign, 30 November 2019

© Jean-Philippe CazierCleews Vellay was thirty years old when he died from AIDS in Paris in 1994. For ten years, he had been la présidentE (presidentrice) (his own preferred title) of ACT UP Paris. On 30 November 2019, a pedestrian area in front of the former ACT UP office was named Promenade Cleews Vellay (see Figure 21) and a board was attached to the former office.

19. AIDS memorial benches (2004)

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201403/020Many benches are placed in AIDS memorial gardens and groves, some of them are dedicated to a loved one. In Edinburgh, the AIDS memorial ‘Life Tribute’ made in 2004 consists of a bench on the Water of Leith Walkway opposite the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, accompanied by a poem by Isla Paschal Richardson inscribed on a slab:

If I should ever leave you whom I love,

To go along the silent way,

Grieve not,

Nor speak to me with tears,

But laugh and talk of me as if I were beside you there

The healing landscape was already present. From the bench, there is a stunning view of the waters and after 2010 you would see a bronze sculpture in the river basin: a human being in a contemplative pose, one of six sculptures called ‘6 TIMES’ by Antony Gormley, which are all placed along the Water of Leith.

AIDS Memorial of Moldova in Chișinău’s Central Park, 30 May 2013

© Iniţiativa PozitivăThe most impressive public bench is in Central Park in Chișinău and is designed by Ion and Elena David. The AIDS memorial of Moldova consists of 5,300 nuts welded together and representing Moldavian society. At the time of inauguration on 30 May 2013, 1,756 black bolts had been screwed into the bench (to reference how HIV enters the body’s cells), representing the number of people who had died from AIDS in Moldova up to that date (see Figure 22). One can sit on the bench, but the part with bolts does not feel very comfortable.

Un lloc per a la memòria (‘A place for remembrance’) in Sabadell, north of Barcelona consists of an iron bench outside the Hospital Parc Taulí (2005). The red bench on Bilbao’s Paseo del Arenal (2017) is probably the most comfortable one.

20. Uncategorised AIDS memorials

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201403/021

Chueca an Dante Parking, underground car park and AIDS memorial, 27 October 2005

© Pablo Orcajo, Teresa Sapey & PartnersA great number of memorials cannot be assigned to any category. Two of them will be presented here.

Chueca an Dante Parking is a car park underneath Plaza Vazquez de Mella in Madrid’s gay neighbourhood Chueca. When Teresa Sapey was asked to transform this parking garage into an inviting environment, she paid tribute to the location. Realised in 2005, the colour red dominates the spaces, which feature illuminated text from Dante’s La Divina Commedia, Inferno, canto V in neon letters (see Figure 23):

Amor que amar obliga al que es amado,

me ata a tus brazos, con placer tan fuerte

que como ves, ni aún muerto me abandona…

(Love, that exempts no one beloved from loving,

Seized me with pleasure of this man so strongly,

That, as thou seest, it doth not yet desert me…)

Along the pedestrian entry, photographs depict kinds of love, and on the outside, a large Red Ribbon towers over the car entrance.

HIV/AIDSmonument on the IJ in Amsterdam on International Candlelight Memorial, 21 May 2017

© Jörn WoltersThe location for the HIV/AIDS monument in Amsterdam was carefully chosen: the now beautified quay on the IJ inlet east of Central Station stands for trade overseas, exchanging goods as well as diseases, a place for prostitutes and drug addicts a few decades ago, with the former bar of Amsterdam’s gay motorcycle club across the street and car-cruising for gays on its eastern end. The giant abacus with scarlet beads designed by French artist Jean-Michel Othoniel refers to numbers which shift in importance: from T4 cells, viral load, deaths and pills to years with HIV – ‘Living by Numbers’. The HIV/AIDS monument was unveiled on World AIDS Day 2016 – not to be confused with the ‘Homomonument’ on Westermarkt, erected in 1987.

Due to the construction of a new ferry dock, the HIV/AIDS monument was taken down in June 2020 and temporarily stored in a warehouse. The plan is to return the monument to the same location at the end of 2021.

Designs not implemented

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201403/022The design of memorials is often controversial. In particular, artwork that wants to visualise the disruptiveness of the AIDS pandemic often clashes with the desire of survivors and/or the public for healing and harmonising landscapes. Thus, a petrified tree design for San Diego’s Balboa Park was halted in 1994. Comparable carbon fibre poles with a charred wood walkway for the AIDS Memorial Grove were also not implemented in 2005.

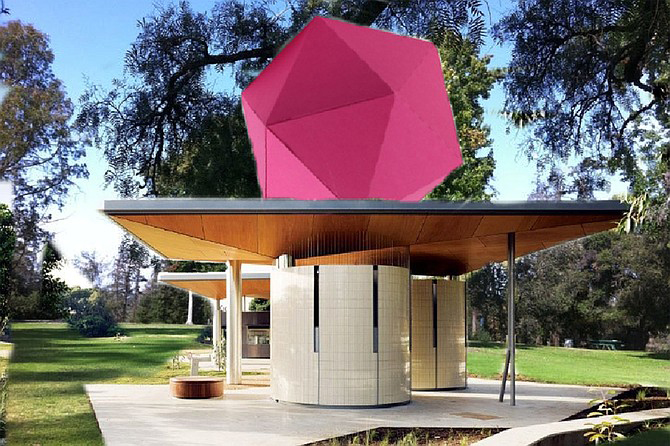

(Top) 'Infinite Forest', winning design for the New York City AIDS Memorial Park at St Vincent’s Triangle, 30 January 2012

(Bottom) New York City AIDS Memorial at St Vincent’s Triangle, 23 December 2019

© Guillaume Paturel for studio ai architects 2011 / Adrian Sas for NYC ParksThe ‘Infinite Forest’ was the winning design for a new memorial in front of former St Vincent’s Hospital in New York. An international team of architects at Brooklyn-based studio a+i created a park lined by three mirrored walls offering infinite reflections of the white birch trees and visitors inside (see Figure 25 (top)). People objected to the design because birds would fly into its mirrors and because they did not like looking at the outside of the wall. Studio a+i’s alternative design, a trellis with a green triangular canopy, was not accepted either, leaving the New York City AIDS Memorial at St Vincent’s Triangle on 1 December 2016 with a metal pavilion and a reflection pool freed of any organic matter. The artist Jenny Holzer added sections of Walt Whitman’s poem ‘Song of Myself’ as text carved in the granite slabs.

Neglect, vandalism, and loss

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201403/023AIDS memorial gardens need maintenance. If volunteers are missing or the initiating organisation ceases to exist, the gardens can overgrow and sink into oblivion. This is what happened in York, Pennsylvania. After I had asked for information on the 1996 York AIDS Memorial Garden at the York Daily Record newspaper, the editors reacted with a story titled ‘Dutch group focuses on York AIDS memorial’ (Argento, 2013). Three months later, a new group adopted the Serenity Garden of Hope, as the garden was originally named, and organised a clean-up, uncovering the Red Ribbon embedded bricks featuring the names of York County fellows residents.

In the late summer of 2003 Jearld Moldenhauer discovered that the memorial birch tree that he had planted in Toronto’s Cawthra Park for the late James McPhee had been removed by a city worker ( Bride, 2004, p 52, footnote 6). Public sex in the park was under debate before the addition of the solid AIDS memorial and in 1999, the Community Action Policing (CAP) initiative tried to clean-up ‘inappropriate’ behaviour by cutting down trees and shrubbery behind the AIDS memorial (Bride, 2004, pp 49–52). Since the upgrade of the park for World Pride 2014, the first four brass plaques (including the one for James McPhee), that had still been situated on the rear side of the AIDS memorial and which were documented by me in 2012, are missing.

As a ‘decentralised’ project of EXPO 2000 in Hanover, the final stones of NAMEN und Steine have been placed in the former explosives bunker of Schaumburg Quarries and complemented with a sound installation recorded in St Paul’s Cathedral, London, by Anthony Moore. The adventure park Steinzeichen outside the town of Rinteln never actually integrated the memorial in their adventure park so that nature reclaimed it. After the company that owned it went bankrupt in 2016, it became a lost place.

The Church of St Veronica on Christopher Street, New York City, harbouring an AIDS memorial in the choir loft, closed its doors in 2017. After a group of parishioners rallied to have the church reopened, taking the cause all the way to the Vatican, the Decree of Closure was rescinded by Cardinal Timothy Dolan as of 2 July 2020.

The base of the Brighton and Hove AIDS memorial was vandalised twice in 2011 and also in 2012 and 2014 with graffiti or posters. The Zaragoza HIV-AIDS memorial has even been destroyed by cutting its four legs.

Six out of 13 digital memorials listed on AIDSmemorial.info are not accessible anymore. Five have been taken offline and the Museum of AIDS in Africa did not upgrade their website to meet the requirements of the webserver. Even the NAMENproject Nederland was not able to prevent valuable data from being lost during transfer to a new webserver.

Scrapbooks of remembrance might have been created in many organisations. After they ceased to exist, their content usually goes to a public archive. If scrapbooks stay in private hands, they are in danger of being thrown away upon the person’s death.

Johannesburg AIDS Memorial Wall, 2 June 2003

© Gaara ProjectsThe first physical AIDS memorial that has been intentionally dismantled is that of Johannesburg. Unveiled by the mayor on World AIDS Day, 1 December 1998, the AIDS Memorial Wall stood outside the Artist Proof Studio (APS), then on 57 Rahima Moosa Street. Etched brass plates, each bearing the name of a loved one who had died as a result of AIDS, were affixed to the curved, concrete structure. Due to a lack of funding no further plaques have been added. In 2007, the wall was pulled down to make room for a new development. But what happened to the brass plates? Did they make it into Museum Africa whose entrance is less than 300m away?

Conservation

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201403/024

(Top): Block from the Australian AIDS Memorial Quilt, various makers, Sydney, 1992, on display at the Museums Discovery Centre, Castle Hill, in 2011. Gift of Sydney Quilt Project, 24 November 2011

(Bottom): Dutch quilt block 03 being unfolded by curators during the workshop ‘Material Culture of Health Activism’ on 20 June 2019 at the Science Museum in London

© Christopher Snelling for the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, Sydney / Trustees of the Science Museum, LondonAustralia is the first country to have its AIDS Memorial Quilt preserved in a museum. In 2007, 97 quilt blocks from Sydney were transferred to the Powerhouse Museum. The Museum worked together with the source community to gather information about the people on the panels and their makers. For a few years, in a rotating programme, one quilt block was always on display at the Museum’s Discovery Centre in Castle Hill (see Figure 27 (top)). In other Australian cities like Melbourne, Adelaide and Perth, quilt blocks stayed with the source community in order to easily display them at various events.

Sweden followed Sydney in 2010 (Världskultur Museerna in Göteborg), and then New Zealand 2012 (Museum Te Papa in Wellington), Belgium 2014 (Museum aan de Stroom in Antwerpen), and Spain 2016 (Museu d’Historia de Catalunya in Barcelona) added their whole national AIDS Quilt to a museum collection.

After an international master class at the Reinwardt Academy in Amsterdam had addressed various aspects of the Dutch Quilt in early 2013, it became clear that the total collection of thirty quilt blocks should not be taken by one Dutch museum (Meijer-van Mensch and de Wildt, 2014). Instead, by the end of 2020 the Netherlands will have spread all of their thirty quilt blocks over exactly twenty national and international museums and archives, among others the Science Museum in London. Dutch quilt block nr. 03 was ceremonially unfolded as a special feature of the workshop ‘Material Culture of Health Activism’ on 20 June 2019 (see Figure 27 (bottom)). The University of Amsterdam (Schalkwijk, 2015), the Nederlands Openlucht Museum (Dutch Open Air Museum) in Arnhem (Elpers and Posthouwer, 2017) and the Musée des Civilisations de l’Europe et de la Mediterranée MuCEM in Marseille (Molle, 2019) used their quilt blocks as research objects.

With a total of more than 5,950 blocks, the US AIDS Memorial Quilt deserves a museum to itself. In early 2020 it returned from Atlanta to San Francisco under the stewardship of the National AIDS Memorial, which already cares for the AIDS Memorial Grove.

Future AIDS memorials

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201403/025

San Diego AIDS Memorial for Balboa Park, satire, 21 August 2020

© Walter Mencken, San Diego ReaderAfter a petrified tree design for San Diego’s Balboa Park was halted in 1994 (see Designs not implemented, above) the city now plans an AIDS memorial in a section of the novel Olive Street Park, on a platform overlooking Maple Canyon. The location is opposed by the LGBTQ+ community as well as the neighbourhood. Ground-breaking was planned for 2020 but is delayed. In August 2020, the San Diego Reader published a satire classified as ‘Almost Factual News’ titled Protest leads to position shift for AIDS memorial – Back to Balboa, which brought feelings into the open (see Figure 28; Mencken, 2020). But is the argument ‘Because gay men were the population that was hardest hit by the AIDS epidemic, an AIDS memorial is best suited at a “gay” location’ a valid one?

The AIDS Memorial Pathway in Seattle integrates a variety of components (AIDS Memorial Pathway, 2020). It already comprises the history of AIDS in Washington State, short stories on video, and a list of names lost to AIDS based on a compilation of Seattle Gay News from 1997 on their website. The physical pathway itself will consist of a large sculpture at a central plaza and a community room near the subway station, a series of tableaus showing protest signs, and three life-size laminated glass sculptures – titled ‘Monolith’, ‘Reverie’ and ‘Lambda’ – in the adjacent park. Completion is expected in 2021.

In ‘Stories – The AIDS Monument’ to be constructed in West Hollywood, stories will play a pivotal role (Stories – The AIDS Monument, 2020). Their website already shows a timeline of AIDS in the US, and some video stories. For written stories, they refer to the Instagram account @TheAIDSMemorial. The physical memorial will consist of a field of 341 vertical strands on a raised platform. Ground-breaking is expected in summer of 2021.

In July of 2020, The AIDS Memory UK Campaign reported that an AIDS memorial garden for London will be designed by Flo Headlam and Jennifer Mangan with artwork by The Sinistry aka Bert Gilbert and Izzet Ers (Isabel de Vasconcellos Contemporary Art, 2020). A location has not been found yet but they aim for completion of the garden in 2021, marking the fortieth anniversary of the official recognition of the disease by the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

Competition for memorials

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201403/026

‘Fog rolling down the Hudson – 26 March 2015 (with remnants of Pier 49)’

© James Prochnik www.jamesprochnik.comMy favourite memorial is the ‘other’ AIDS memorial in New York at Hudson River Park (2008) – only 900m away from the one at St Vincent’s Triangle. It consists of a curved stone bench with a quote from a Swedish folk song:

I can sail without wind,

I can row without oars,

but I cannot part from my friend

without tears.

The remnants of Pier 49 remind me not only of the lives lost to AIDS but also of my practical coming-out as a gay man in a bar called Badlands on Christopher & West Streets in 1979 and the good times I had on these piers.

It is not unusual that cities have more than one AIDS memorial. What has alienated me is the marketing of the new memorial on St Vincent’s Triangle as the ‘first AIDS memorial in New York City’. While the claim has in the meantime been taken off the initiator’s website, it is still documented in news reports e.g. in Architizer (Keskeys, 2016) or Gay Times (Megarry, 2016). It’s about time that they show the fellow memorial at Hudson River Park on their map! The initiators of the novel AIDS monument in West Hollywood called ‘Stories – The AIDS Monument’ did not claim to be the first, but they also ignore the existence of the earlier memorial: the West Hollywood AIDS Memorial Walk present since 1993 with brass plaques in the sidewalk of Santa Monica Boulevard less than 200m away.

Manchester has shown that you can act differently. Their ‘Beacon of Hope’ integrated the earlier AIDS memorial tree. In New York City, it was XDEA studio that proposed to link the three West Village AIDS memorials (the third is in Church of St Veronica) via a performance and light installation, now scheduled for 2021 (Johnson et al, 2018). The penchant for superlatives is, of course, not limited to the New World: it was embarrassing to read the press release of the Aids Fonds in 2016 claiming the HIV/AIDS monument in Amsterdam to be the first in Europe.

Some more recent memorial projects have attracted a lot of money. The novel New York City AIDS memorial at St Vincent’s Triangle had a budget of $6 million; The Story – The AIDS Monument in West Hollywood has a budget of $4.5 million. Besides well-founded goals to preserve the history of AIDS, they are becoming a business with jobs attached. This is in stark contrast to initiatives in less rich countries – the Museum of AIDS in Africa, for example, does not have the resources to upgrade their website.

The role of cultural heritage institutions

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201403/027This photo-essay shows only a selection of an extreme variety of AIDS memorials that have evolved from spaces of mourning and healing into spaces for empowerment of survivors. In later memorials, caregivers, scientists and activists are explicitly included as well. The trend can be seen through the different categories of memorial described above.

AIDS memorials are certainly cultural heritage. Monuments and other immobile memorials should be officially registered in national heritage registers. Depending on the country, these are organised on the national, regional, county and/or municipal level, but AIDS memorials are hardly officially recognised as cultural heritage.

But more important is the ‘living heritage’ as a means of narrowing the generation gap by telling history and lending contemporary value to the monument. Besides World AIDS Day, the International AIDS Candlelight Memorial, and charity events like an AIDS walk, AIDS memorials are frequently used as an integral part of LGBTQ+ Prides. Haemophilia groups sometimes created their own AIDS memorials (United Kingdom, Canada, New Jersey) or a separate location within an existing memorial (Hemophilia Circle within the National AIDS Memorial Grove in San Francisco). The London-based International Network of People who Use Drugs (INPUD) has declared 21 July as International Drug Users Remembrance Day (since 1998) and also realised several monuments but without specific reference to HIV, AIDS or hepatitis C.

Movable memorials are the collection targets of museums and archives. When looking for a new home of the Dutch AIDS Memorial Quilt, both museums dealing with the history of medicine and/or natural sciences we approached were not interested in the first place. Rijksmuseum Boerhaave rejected our donation because ‘the quilt does not fit in our collection policy of scientific heritage’ (Grob, 2014), the German Hygiene-Museum because ‘our collection focusses on AIDS awareness campaigns using the poster medium’ (Vogel, 2019). Only in the run up to the exhibition Besmet! (‘Infected!’), which opened 16 July 2020, did Rijksmuseum Boerhaave accept the quilt block (Parry, 2020). The Nigerian AIDS Memorial Quilt has however been lost. That might not be a loss for the AIDS Memorial Quilt as such but it is a big loss for the cultural heritage of Nigeria. In 2004, the Världskulturmuseet (Museum of World Culture) in Göteborg started a three-year project No Name Fever – AIDS in the age of globalization. Their exhibition was structured around emotive themes: denial, fear, anger, lust, sorrow, despair and hope, and displayed two quilt blocks, one from Sweden and one from the Philippines. In a collaboration with Museion at the Göteborg University, interdisciplinary research resulted in a bundle of 13 papers (Follér and Thörn, 2005). In 2007, a reduced part of the exhibition travelled to Red Location Museum in Port Elizabeth, South Africa, complemented with South African content: No Name Fever – uGawulayo.

Block 22 of the Dutch AIDS Memorial Quilt in the stairwell of the Museum Europäischer Kulturen in Berlin

© Ute Franz-Scarciglia, Museum Europäischer Kulturen - Staatliche Museen zu BerlinInclusion in the collection of a museum usually means withdrawal from the source community. Large objects like 3.80m x 3.80m blocks of AIDS Memorial Quilt can usually not easily be shown to interested parties. Léontine Meijer-van Mensch, when deputy director of the Museum Europäischer Kulturen (Museum of European Cultures) in Berlin, implemented a semi-open way of storage that enables people to see the object upon request: the most ‘European’ of the thirty Dutch quilt blocks was lashed down to a wooden frame encompassed by a movable light shade to protect the textile (see Figure 30).

Red Ribbons are easier to collect. A Red Ribbon brooch designed by English jewellery maker Andrew Logan was donated to the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) archives twice: one by his friend Lyn Rothman, the founder of AIDS Crisis Trust, in 2015 and another one by the artist himself in 2018, as their blogs report. (Surprisingly, I could not find it on their online system.) Blogging has become a powerful means to communicate about recent developments in museums as shown by the Amsterdam Museum (anonymous, 2012, 2016, 2018; de Wildt, 2013, 2014, 2018; de Wildt and Schalkwijk, 2016; van der Britt-Marie, 2013).

Archives are the specialist repositories for objects consisting of paper, including emotional objects like a scrapbook. They are of crucial importance in order to detect treasures of the AIDS era. Prerequisite is that legacies of people that died in the time of AIDS, and organisations related to HIV and AIDS that ceased to exist, need to be disclosed and the content needs to be available online. Secondly, archives need to offer disclosure rules and scientific and public access rights for records that are privacy sensitive. This also holds for ecclesiastical archives. Archives can also play an important role in the digitisation of their archived material, e.g. of magazines from various communities.

Heritage institutions can play a much more proactive role. In order to preserve the cultural heritage with respect to HIV and AIDS, archives, collections and museums harbouring AIDS-related objects on the one hand as well as initiatives for AIDS memorials on the other face the same two important challenges: How can they become inclusive as much as possible by proactively building partnerships with under-represented groups (drug users, sex workers, people with low income, homeless, migrants, ethnic minorities, …)?; and, How can they exchange knowledge as much as possible by proactively building partnerships with countries that have less resources and supporting local initiatives (e.g. HIV and AIDS Museum in Uganda)?

These partnerships could be a means to enhance social inclusion in museums.