Black Arrow R4: the object behind the screen

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221706

Abstract

The Black Arrow R4 rocket passed through many hands on its way to and within the Science Museum. Sets of relationships were established around and enacted through the object at each stage of its journey, so imbuing it with a range of meanings. This journey was in turn built around preceding sets of circumstances, people and relationships that contributed to the rocket’s creation as an artefact. This paper seeks a better understanding of the Black Arrow rocket as a museum object. It does this first by reviewing the relationships mediated by it during its ‘lifetime’ before and at the Science Museum. In so doing it seeks a voice for the ‘mute’ object, one that can bear testimony to the beliefs and actions of those people involved with it, so foregrounding previously hidden or undervalued meanings of the museum object. However, the paper touches briefly on whether the rocket itself, as a physical object, may be encountered in its own right – as a ‘thing’ in the gallery and not necessarily tied to any suggested or implicit meanings.

Keywords

Black Arrow rocket, gallery display, history of science and technology, meanings, Museum, objects, Prospero satellite

Black Arrow R4: the object behind the screen

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221706/002The Coronavirus pandemic has driven more people to online working and use of the internet as a substitute for physical encounters. This trend has been reflected in the numbers of visitors accessing the Science Museum Group’s online collections pages, currently averaging more than 150,000 per month.[1] The pages offer a range of entry points to the collections with ‘New Stories’ providing some themed collections-based narratives written in the main by museum staff.

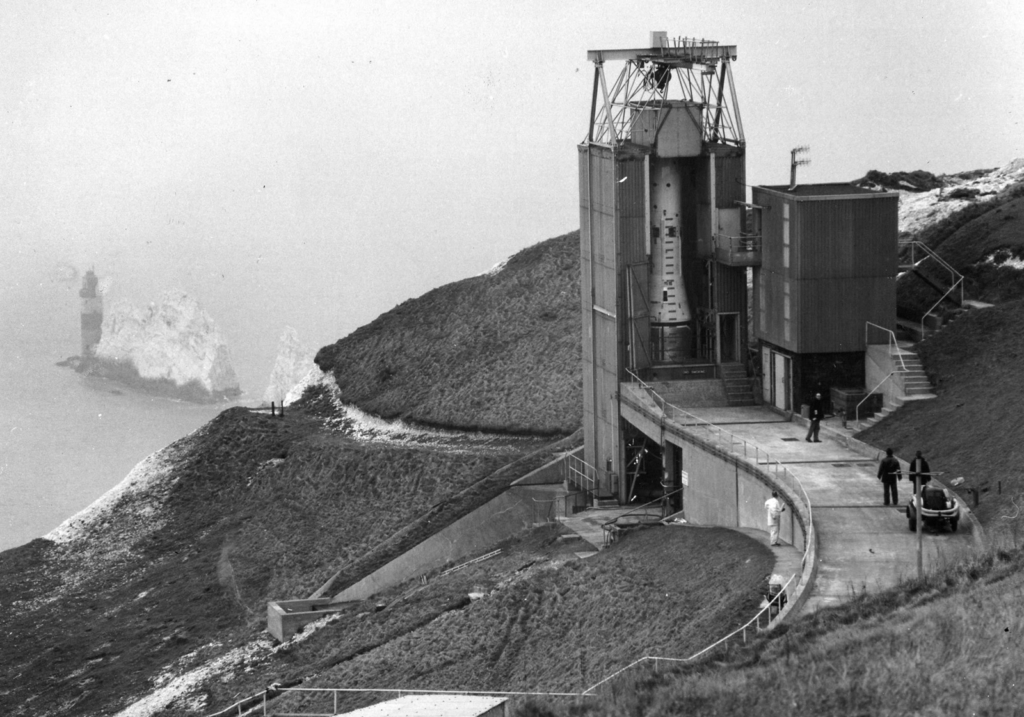

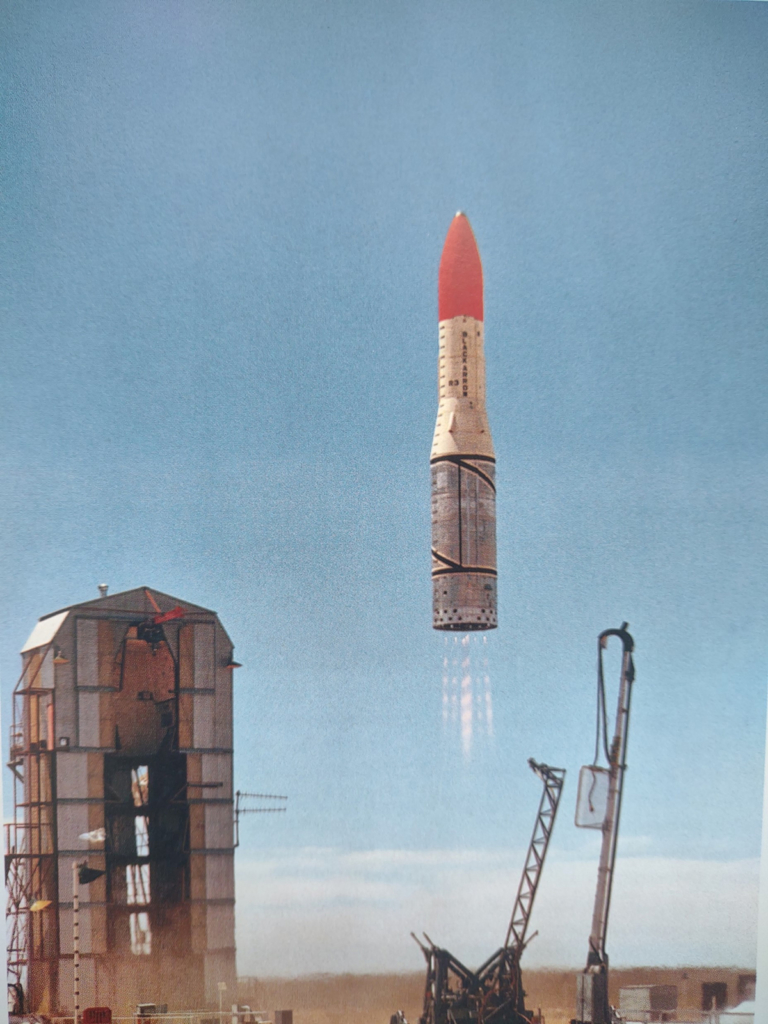

In October 2021 ‘In Pictures: The Black Arrow Rocket’ was added under the ‘New Stories’ category [https://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/objects-and-stories/pictures-black-arrow-rocket]. This offered a brief illustrated history of the only launch to date of a British satellite by a British rocket, performed on 28 October 1971.[2] Although a British programme, the launch was carried out in South Australia at the Woomera Rocket Range of the Anglo-Australian Joint Project (Morton, 2017). The following focus on and around the British-built rocket and satellite hardware can be situated in a broader context, following new understandings of space exploration positioned in global and post-colonial perspectives.

The storyline of this new narrative was composed around contemporary images of the Black Arrow programme and the Science Museum’s representation of it in its collections, and principally via a surviving rocket – Black Arrow R4 – and the Prospero satellite flight spare, both on physical display in the Museum’s Exploring Space gallery.

Alongside a steady increase in the number of visits to the Science Museum Collections online pages during the pandemic, there has been, inevitably, a sharp fall in the number of physical visits to the Museum when it was either closed to the public completely or open for a restricted number of days each week only. Physical visits to the Museum will surely pick up as the effects of Covid start to fade but the episode has underlined the importance of representing the Museum’s collections and objects online. These web entries will continue to rise in number as the Museum moves towards its ultimate ambition of placing all collections online. This quantitative objective will be accompanied by ever more sophisticated systems for cross-referencing dispersed sources of digital information relevant to the Museum’s collections.[3]

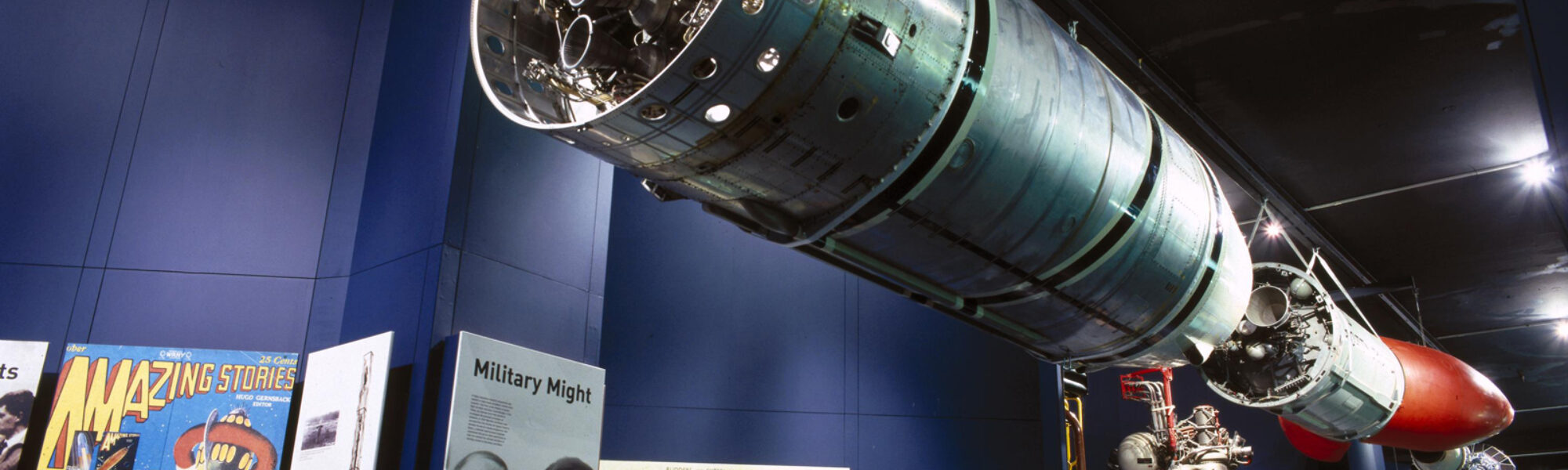

What then for the object as a physical entity in years to come? What role does a physical encounter with an object or a group of objects play when more and more of the world is played out in cyberspace? Collections of objects do not come cheap; they can be costly to acquire, preserve and to store (or display). The Black Arrow R4 rocket, currently suspended from the ceiling of the Exploring Space gallery, is large, heavy and would be awkward to move (see Figure 1). Any future relocation of it between galleries, stores or external borrowers would be expensive in time, resources and cost. With its virtual presence assured within the Museum’s online offerings what role would its physical existence play in the future?

DeVorkin points out that ‘Anyone sensitive to the immense costs involved in collecting and preserving the material legacy of modern culture must question such expenditure at one time or another’ (DeVorkin, 2006). Germane to DeVorkin’s observation is a deeper consideration of what museum collections bring to understandings of the history of science and technology, whether for the scholar or for the lay person. Thomas suggests they offer a singular benefit, one that disrupts received wisdom. When a curator is perhaps surveying a collection or a prospective object or group of objects there is the chance they make a ‘discovery’ in doing so (Thomas, 2010). This could be from beyond the museum but equally so from within – found in a search of the database or happened upon in the store. This, Thomas suggests, offers a particular methodological potency where the encounter between curator and object allows a ‘responsiveness to forms of material evidence beneath or at odds with canonical [and brings the question of] what else is there to the fore’ (Thomas, 2010).[4] In other words, just as newly discovered archival material or documentation can challenge existing histories and understandings, so too can the artefact.

DeVorkin, in his consideration of collected spaceflight artefacts, lists five attributes the object can possess (DeVorkin, 2006, pp 598–599). He suggests it can validate a historical event.[5] The object’s existence is material evidence for the event having occurred. The object could also celebrate a historical event. This paper, indeed, has been written, with the Museum’s Black Arrow object the subject, to mark the 50th anniversary of its predecessor’s historic flight. DeVorkin goes on to say the object can inspire through its standing as material evidence of technological challenges overcome, so illustrating basic principles of science and technology. The object can also illuminate a hitherto hidden aspect of history, perhaps related to the reasons for its preservation.

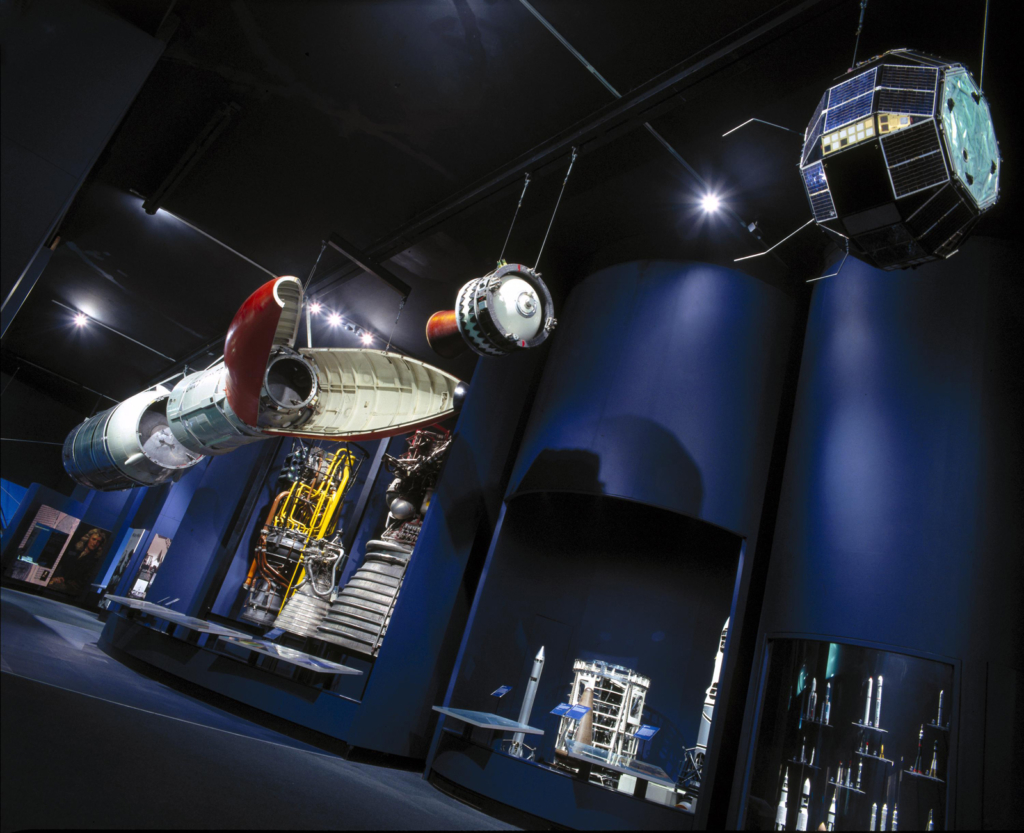

Finally, DeVorkin argues that an object can act as a stimulant for further research and analysis. The Black Arrow R4 rocket acted strongly in this manner when the author worked with members of its original manufacturing company (Westland Aircraft) during the relocation and reworking of its display in the Science Museum. It was moved from a floor-mounted display (see Figure 2) to a suspended one, its stages separated and its apogee (third stage) motor and satellite added.

This exercise drew heavily on the original team’s knowledge and expertise which in turn imbued the author’s own awareness of and interest in the rocket’s history. It augured a curatorial re-examination of the Museum’s collection of rocket engines and the realisation or ‘discovery’ of a common heritage, with the Black Arrow’s Gamma units (see Figure 3) a near culmination for a particular type and capability of rocket propulsion (Millard, 2001).

This curatorial interest broadened to embrace many aspects of the rocket’s existence prior to its acquisition and display by the Museum. Alberti speaks of an object’s ‘biography’ where it, inevitably mute and being unable to speak for itself, can nevertheless signify different meanings attributed to it during its ‘lifetime’, so allowing us to learn more of the human agents – their motives and priorities – that acted with and upon it (Alberti, 2005).

Black Arrow R4 was acquired by the Science Museum in 1972. Its availability for acquisition was communicated to Museum Director David Follett by Keeper Brian Lacey in January of that year.[6] Leading with the practicalities of such an acquisition, a description of the rocket and the Black Arrow programme history, Lacey, following an inspection visit to the rocket at its manufacturer’s premises on the Isle of Wight, justified his proposal to acquire:

It is the only 100% British space effort (British launch vehicle and satellite) and the programme will probably never be repeated.[7] It will in time become an historic relic of this country’s space technology programme.

It is an example of a conventional three stage launch vehicle and therefore will be a good technical exhibit.

The historicity of the object is made plain here but so too its potential for technological interpretation and understanding. Lacey went on to list additional reasons, largely of practicality, that would strengthen the case for its acquisition:

It is in ‘as new’ condition. It is a very compact rocket vehicle. It has a self-supporting structure (i.e. no pressurising of tanks necessary or other costly maintenance tasks needed when vehicle is erected in vertical configuration). The third stage, fairings and satellite can be placed on exhibition when the latter is acquired after the SBAC Show in September 1972. The exhibit can be backed up with full technical information.

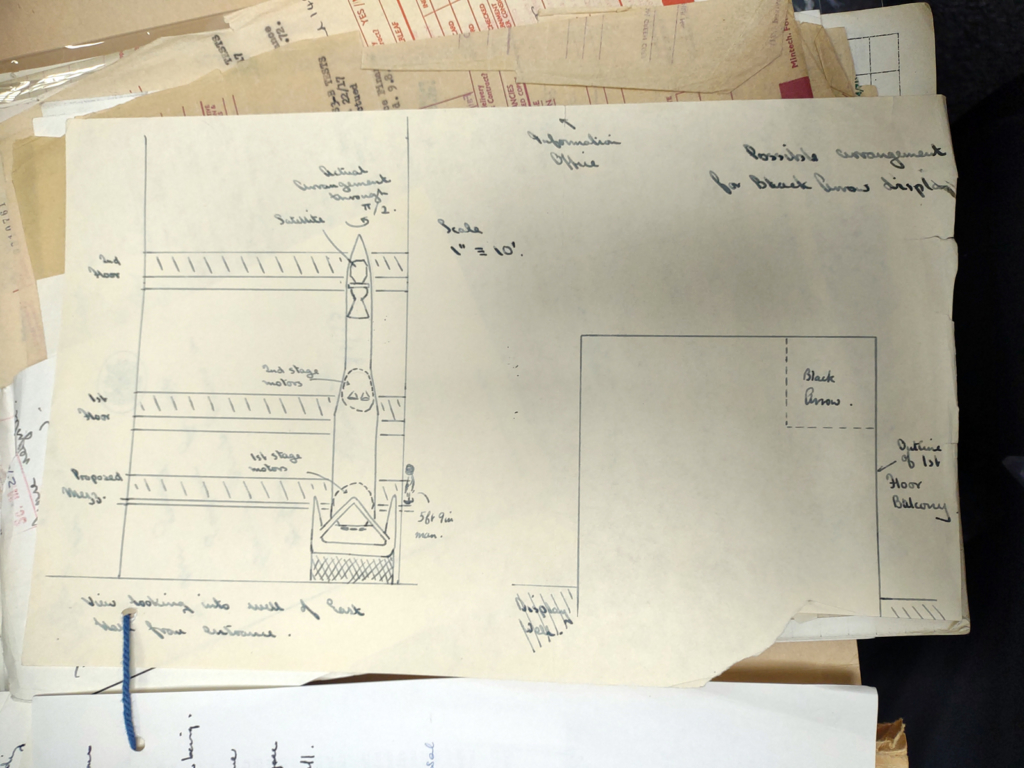

The potential for vertical display was returned to a year later when Lacey’s colleague, John Becklake, argued for the now accessioned rocket to be so exhibited in the East Hall of the Museum (see Figure 4). This was the second time such a suggestion had been made since the rocket had been added to the collection. The renewed attempt was prompted by preparations underway for the new mezzanine floor in the East Hall of the Museum: ‘the mezzanine floor will provide another viewing level for the rocket vehicle.’

Director Margaret Weston[8] responded, ‘it occurs to me that Black Arrow would go rather oddly with the existing Motive Power galleries’, but adds, ‘the mezzanine floor around the East Hall proposal has had to be dropped for the time being’.[9]

Weston’s first point is redolent of questions posed by Thomas of the arrangement of displayed objects: ‘Where does difference become incommensurability? When is it wrong and when might it be right to put incommensurable things together’ (Thomas, 2010). Weston implies that a visitor’s interpretation of the objects in question – both the rocket and the nearby power units – would each be affected by their close proximity to each other.

Her second point foregrounds a more prosaic aspect of object display, namely the physical opportunities for and the barriers to the display of an object or group of objects. Such factors both dictate whether it is physically possible for an object to be considered for exhibition but also how any physical encroachments from nearby displays or the gallery fabric itself, or other factors, might influence, say, the positioning of the object.

Black Arrow R4 was eventually displayed horizontally on the floor of the Exploration of Space gallery (1986).[10] In 2000 it was repositioned in the same gallery space but hung from the ceiling (see Figure 5).[11]

The second location option emerged as a result of works elsewhere in the Museum. The removal of the Apollo 10 command module and the V2 missile from Exploration of Space into the new, adjacent ground floor gallery, Making the Modern World, necessitated a sizeable deconstruction of the western end of the space gallery. This significantly disrupted sections of the gallery, their narratives and the overarching theming of the gallery itself. Black Arrow had to be moved to create a clear passage for the Apollo and V2 moves but its return was deemed undesirable as it would restrict the passage of the expected increased numbers of visitors passing through the gallery and on to the new Welcome Wing at the western end of the Museum. However, the vacated ceiling RSJ[12] that had supported V2 offered a new location for Black Arrow and following discussions with the Museum’s Estates team and the rocket manufacturing company’s retired engineers the rocket was duly lifted into its present suspended location (see Figure 5).

These episodes, illustrating well Alberti’s conception of the museum acting ‘as a vessel for the bundle of relationships…between people and people, between objects and objects, and between objects and people…’ (Alberti, 2005) assigned Black Arrow a series of meanings. The first had the rocket, on the gallery floor, as a physical connector between three adjacent gallery sections: ‘How a Rocket Works’, ‘What Rockets do’ and ‘Britain in Space’. So positioned, the rocket was imbued with three respective meanings: as an authentic representation of Lacey’s ‘technical exhibit’ (the chambers of the first stage’s Gamma engine could be touched easily and even swivelled[13] – ‘How a Rocket Works’); as an example of a satellite-launch vehicle (‘What Rockets do’); and as a historic relic (this British programme was, indeed, ‘never [to be] repeated’).

These meanings were duly usurped by one assigned by other Museum teams in which the rocket was considered an obstacle to visitor flow through the gallery. It would literally block the easy movement of visitors through the Museum – a pinch point where the gallery would become unduly congested, so worsening the visitor experience.

That this issue could be circumvented and the rocket re-accommodated in the gallery, in a new location, was providential and emergent, arising from a set of circumstances and due largely to the availability of the recently vacated ceiling display space where the V2 missile had been suspended.

Black Arrow before the Science Museum

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221706/003The Black Arrow programme was cancelled by Prime Minister Edward Heath’s government in 1971, shortly before R3 – the fourth rocket in the Black Arrow series and the second to attempt an orbital launch – boosted the Prospero satellite into a near-Polar orbit of the Earth (Millard, 2001).

Lacey’s memo to the Science Museum Director came just three months later and reflected both the opportunity to acquire and the urgency with which the Museum had to reach a decision: the rocket’s sponsoring Government Departments DTI (Trade & Industry) and MoD (Ministry of Defence) had until 31 March, just under three months later, in which ‘to wind-up Black Arrow’.[14] The costs of preparing the rocket for transfer to the Museum (some £5,000) would be absorbed by the DTI, leaving the Museum to cover its carriage from the Isle of Wight to its west London store.

For the government and the rocket’s manufacturing company the rocket was a drain on resources and finances; like its perceived blocking of visitors’ progress through the Museum, an encumbrance that had to be dealt with swiftly.

Throughout its ‘pre-Museum career’ the Black Arrow programme, as embodied in the surviving R4 vehicle, was perceived as different things to different people. To its design authority – the Ministry of Aviation’s Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) – Black Arrow, as it came to be known, would provide a means of testing in the space environment, for extended periods of time, new satellite components and systems (Millard, 2021). The RAE’s newly formed Space Department’s roles included satellite research and development, this to help British industry tender successfully for the telecommunications satellites the European Launcher Development Organisation’s (ELDO) Europa rocket would be launching. Black Arrow was seen as an investment by the Ministry of Aviation and as a requirement by RAE’s Space Department. The Treasury, however, was far more sceptical and even dismissive of such a need with one official stating, ‘we do not need satellites for our own purposes. The case for developing them, either alone or in association with Europe, rests upon the arguments of prestige [author’s emphasis], technological spin-off, foreign exchange earnings…and the need to provide jobs for design staffs etc.’ (Butler, 2016).

If Black Arrow was perceived by some as an object of prestige then this meaning in itself was open to different interpretations. The concept was a moot point with official and ministerial voices differing in their understanding of the term. Minister of Aviation Julian Amery argued that ‘unless alone among major European countries, the U.K. is going to be content with exclusive reliance on international organisations and to abandon all national work in space – and I do not regard such a policy as defensible – we ought to go ahead [with Black Arrow]’.

On the other hand, F R Barratt, Under Secretary at the Treasury, voiced concerns that space in general ‘will turn out to be an even bigger economic dud than the Concord[e]’ and Black Arrow, if approved, would be for political and ‘emotive’ reasons (Butler, 2016). For Amery prestige was a positive quality while for Goodson it was negative.

Amery’s understanding of Black Arrow as being totemic of Britain’s aspirations to be a technologically advanced nation could perhaps be interpreted also as a reflection of his own political priorities and motivations. In the Summer of 1964 Amery was conscious of the nearing general election, to be held no later than the Autumn of that year. Prime Minister Sir Alec Douglas-Home’s Conservative government was now perceived by many as an old-fashioned elite led by an out-of-touch landed gentry such as Douglas-Home and his predecessor Harold Macmillan. Harold Wilson’s Labour party, on the other hand, was associating itself with modernisation and in particular the championing of science and technology as a means for re-fashioning the economic and social development of the country. Following the promise of extra funds from industry over cocktails at the Farnborough Air Show, Amery staged an impromptu press conference announcing Black Arrow to the world and effectively forcing it through as a project. Amery believed in Black Arrow as a technological project but perhaps saw it also as a political weapon to help fight an election.

Ultimately, Black Arrow was deemed an extravagance by government. After years of restricted funding and two launch failures the Ministry of Aviation initiated an independent review of the programme. It would be conducted by Lord Penney, rector of Imperial College and distinguished nuclear scientist. He concluded that too many rockets were being made for too few available satellites. The government was spending over four times more on the Black Arrow programme than on the satellites it had been developed to launch. As those same satellites could be launched by American rockets the decision was taken by Edward Heath to cancel the Black Arrow programme.

Black Arrow R4 the object

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221706/004The biography of the Black Arrow R4 rocket, before and after it came to the Science Museum, reveals an object with multiple meanings assigned by a host of different individuals and teams working with or talking of it over many years.[15] The meanings are inevitably subjective with none more or less valid than any other. In its present display in the Museum’s Exploring Space gallery any overt interpretation is kept to a minimum. There is one large graphic panel on a nearby gallery pillar carrying an annotated line drawing of the rocket vertically positioned and fully assembled. Above the drawing, set horizontally and disassembled, is a simple drawing of the rocket as it is displayed nearby. The panel text comprises a technical description of the rocket and reference to it being ‘Britain’s only satellite launch vehicle’. It includes a listing of all four Black Arrow rocket launches with dates.

The manner of this object’s display – suspended with its stages separated and satellite added – follows an interplay of human agency amongst and between groups within and outside the Museum. The curatorial team was driven by a wish to retain a large and historically significant object in the gallery when many other objects were to be removed in the gallery’s reconfigured design, this despite pressure from other Museum agents to remove it also. The feasibility of suspending it, from the providentially vacated RSJ that had supported the V2 missile, drew input also from the Museum’s Estates and Design teams, the local authority quantity surveyor, the rocket’s original makers and the contractors employed to supply its supporting strops and shackles and to lift the rocket into place. These players imbued the object with a range of respective meanings depending on their own sets of perspectives and priorities. Such was the case in its ‘career’ before the Museum when it was seen in different ways by different people: by ministry scientists, engineers and officials, by politicians and industrialists and by commenters reporting on and interpreting the programme’s progress.

The rocket’s minimalist display, however, is in part intended to offer the visitor an opportunity to see the object purely as a physical thing, relatively free of accompanying interpretative baggage. Dudley talks ‘about the value of a powerful response to an object just for itself, and not how it might enhance learning or appreciation of the wider aspects of an exhibition’ (Dudley, 2012).

Once the possibility of displaying Black Arrow in the air was shown to be possible the subsequent work, planning and preparation by the teams involved, and particularly Curatorial and Design, was driven as much by the spectacle and visual impact it would present the visitors as they entered the gallery as anything else. Dudley argues that:

the opportunity to be moved to tears, tickled pink, shocked, or even disgusted to the point of nausea by a museum object is itself a powerful component of what a museum experience can offer – not just as a step on the journey to cognitive understanding of an object’s history, or indeed of our own, but simply as a potent and sometimes transformative phenomenon in its own right.

Dudley goes on:

Many of us would not question this claim if it concerned only art, or perhaps conceptual art at least – we can accept that the role of such art is precisely to move, shock, amuse or puzzle us […] These [elemental responses] are not generally understood and used within the world of museums, however (Dudley, 2012).

The Black Arrow’s gallery teams, thinking of the display as, in part, one of spectacle, but also as a static, still-life demonstration of the rocket’s operation, decided to open the two halves of its fairings, implying that the satellite, a little way ahead, had been stowed within when they were closed, as indeed would have been the case. Not unexpectedly, the resulting gape of the rocket drew comparisons to the ‘Angry Alligator’[16] of the Gemini IX-A mission and, more frequently, the scenes in the James Bond film You Only Live Twice when SPECTRE rockets swallowed first an American space capsule and then a Soviet one.[17]

Dudley reminds us that:

our experience of the material world is dependent upon our location, our movement and our interpretations of the data we receive from our senses. And of course, the interpretations we make of what we see, hear, smell, touch or taste are strongly influenced by our cultural and personal experiences and by pre-existing knowledge we may have about a particular object.

Museum objects can rarely be subjected to the full range of human senses, and especially by those of visitors to a gallery or exhibition where touching, and of course tasting, are discouraged or prevented entirely. But that these visitors can draw on more of the senses than those used when viewing virtual objects online (vision and hearing) offers far greater potential for a meaningful engagement with the object by the visitor and the scholar. The object behind the screen is a far richer enticement for the visitor than its image projected on to it.