History of textiles and the Congruence Engine

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221815

Abstract

This essay briefly surveys the rich benefits a project like the Congruence Engine offers to national textile collections. Digital technology provides the means to bring dispersed material, written and oral collections together into one space. However, it also has limitations, and the following will also touch upon these. We finish with an overview of themes such a project should engage with and conclude with a mini study of the pre-Samuel Greg (Quarry Bank Mill) family context and how this links the Mill, the collections held at the Northern Ireland Record Office and West Indian Plantations together.

Introduction

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/Every Man knows his own Affairs…but ask him where his cloths are sold, by whom bought, to what Part of the World they are shipt, and who are the last Consumers of them, he knows nothing of the Matter (

Defoe, 1728

).

Production[1] still dominates the history of textiles, while their changing purpose, use and destination still, despite Defoe’s comments, remain a neglected subject. Where did they go? What was their use and by whom? What is the provenance of the national collections we are examining within the Congruence Engine project?[2] As well as the manufacturers, who were the people, both home and abroad, that communicated designs[3] and who were the traders necessary for their distribution? The Congruence Engine offers a perfect opportunity to significantly broaden the questions textile historians can ask by interrogating and bringing data about the national collections into one place.[4] However, the digital history is still at an early stage and it is difficult to predict where it will take us. Related websites include those that are concerned with trade, labour, legacies of slavery, and gender. There are already plenty of digital sources pertinent to this objective and which the Textiles strand of Congruence Engine can learn from and be aided by. Consider, for example, the digitised 18-volume set of fabric samples put together by John Forbes for the India Office in 1866; this was the source of a major exhibition at the Harris Museum and Art Gallery between 2011 and 2012. These designs are all accessible and available to view now.[5] Google’s Ngram can trace the number of occasions, say, ‘Saltaire’ occurs over time and records the books that mention the place (some of which one can read via the site).[6] Wikidata has a vast depository of digital information that can be profitably utilised to enrich a project like Congruence.[7] The link between West Indian slave plantations and textiles is also proving interesting – The Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery at University College London is an extremely useful digital site for this purpose.[8] However, historians of textiles also have to understand the limitations of digital history and not expect all their ambitions to be realised. The following paper attempts to digest what is and is not possible for such a project, culminating in a suggestion for a series of macro-categories which are tested with a case study.

A universal request from current historians of textiles is for the opportunity to view the material history with the written. Historians focus upon and talk about written sources such as inventories, account books and periodicals, but often without really knowing much about what the things the words describe were like materially. By contrast, textile curators catalogue the objects in their collections but frequently don’t know what words the people who made/consumed them used to describe them. A start here would be collecting digitised artefacts and combining them with formal and informal written records. The latter could be anything from published articles and monographs to trade directories, museum artefacts and film documentaries (such as those preserved by the Congruence Engine partner, the British Film Institute).[9] The historian of textiles, John Styles, has recently bridged this gap with his pioneering work on textile design and quality.[10] A vast central depository of textile sources has been digitised and catalogued at the National Archives at Kew and the Victoria and Albert Museum, but this is not the case for numerous other museums and galleries scattered around the country.[11] For example, other partners on the Congruence Engine such as the National Museums of Scotland, the National Museums of Wales, the National Museums of Northern Ireland and the National Trust hold extensive collections of historical textile sources. Ideally, these need to be connected. There are, of course, many institutions not yet in the group also with relevant collections – consider the Goldsmith’s Textile Collection which holds a global range of textiles, and the London College of Fashion with numerous textile advertisements and photographs, while the Scottish Textile Heritage online resource contains collections from an array of Scottish depositories.[12] It is also important not to neglect the pre-1800 history of textiles.

Optical Character Recognition (OCR) has hitherto predominantly been applied to print but even here the further one goes back in time the greater the difficulty there is in character recognition. This could be an issue when looking at early printed tracts on textiles. The problem is the changing nature of printed font and the organisation of print (digital noise) (Hitchcock, 2013). Another important issue is historical handwriting. It would be wonderful if translating and searching such archival sources was easily possible, but the technology for this still appears limited – unless the records are from the same hand over several years. Nonetheless, handwritten text recognition (HTR) is fast developing and in some cases outperforms OCR – see, especially, Transkribus.[13] This could be utilised for textile production ledgers or even letters emanating from a large textile mill owner over several years. In terms of, for example, machine recognition of textiles we can digitise the surface pattern and design of textiles, but we need to also know the yarn and weave structures.[14]

Obviously, data collecting and creating taxonomies are socially created and thus inevitably biased in various ways. In all but name digital history might be seen as the rebirth of positivism under a new guise (Hunter, 2017; Jones, 2018).[15] I don’t, however, see how creating a project like this can get started without an initial taxonomy for textiles. The arrival of museums may be viewed as warehouses for plundered artefacts from around the British global empire, with the legitimation being understanding the cultures of conquest and arranged around a taxonomy to make them recognisable to the British/western eye.[16] A digital empire is not so different but can be far more malleable, vaster and sympathetic. Consider the case of the recent Benin Digital Project – something we can learn from in organising such an undertaking.[17] This is why the initial taxonomy I specify later in this article is not static; rather, it is a starting point.

Although the Congruence Engine is a domestic/national project, the fundamental role of global connections and, indeed, imperial vectors scream out within the history of textiles. Recognising this in an equal but problematic sense already casts the digital archive/museum in a very different light. Museum textile-related artefacts can both contextualise the written word and enrich the historic environment. In this way the Congruence Engine will by-pass the limitations of relying just on documents determined by historical and political contexts. It is crucial that the written, visual, material and, indeed, audible combine on the same page. The technology is available to digitally recreate the original mill (say Quarry Bank) and hear the textile machines from different vantages. Perhaps Queen Street Mill in Burnley, with its vast preservation of looms in one room, would be even better for this purpose (see Figure 1).[18] This has been done successfully, for example, in the recreation of St Paul’s Cross – the important church in London that was burnt down in 1666 and rebuilt by Christopher Wren as the one we see today. In this recreation you can also hear John Donne’s Gunpowder Day Sermon of 1622 from different positions in the church, which impact upon the way it was heard.[19]

Another issue is the ethical problem of making visible people who may not have wanted to be. There has been much debate on this issue, but it is not entirely clear how one can resolve this – especially if the person is dead. Nonetheless, I concur it is a factor that needs to be taken seriously and debated (Laite, 2020). Equally, access to some collections is more problematic than others and the nature of, for example, a national repository for textiles will direct the future of historical projects. Thus, by the nature of collections there will be a bias towards the post-1800 era, as well as a preference for born-digital records. Crucially, the final user interface will affect research so has to be carefully thought through.[20]

Perhaps the greatest challenge is finding a way to make a digital project meaningful to historians of textiles, curators, the public[21] and computer scientists. Max Kemman concluded his 2019 study Trading Zones of Digital History by underlining the hesitation by historians on how to use computational methods, and by data scientists on adapting their approach to fit historical data sets (Kemman, 2019).[22] At the centre of the Congruence Engine project is the aim to harness an aspect of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning. We know machine learning can find and organise information, but interpretation is still a different matter. Consequently the ‘textiles’ area of the project has commenced with three case studies to see what can be done in terms of understanding a collection and, indeed, bringing different collections together. The first thing necessary is to group and link information together.

Three case studies: Salts Mill and Saltaire, Lister Mill and Bradford, and Quarry Bank Mill and Styall

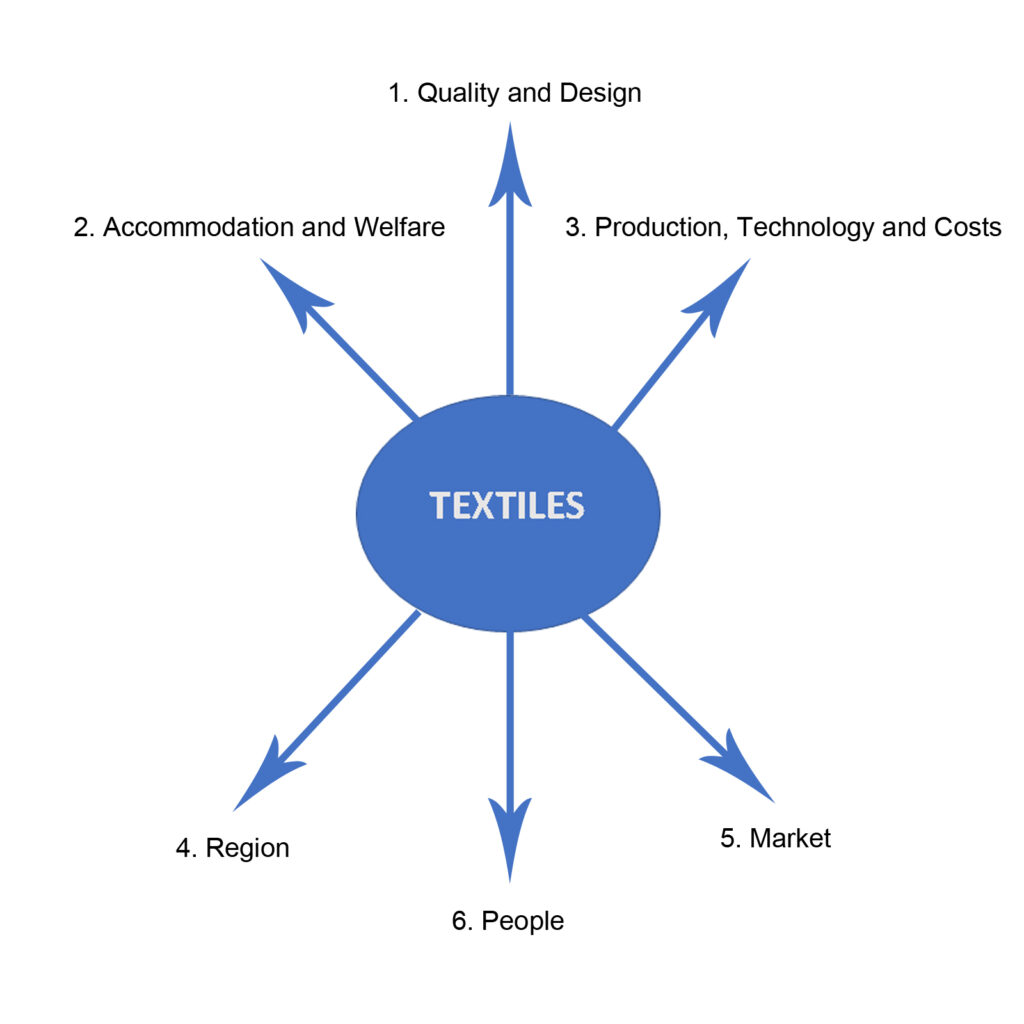

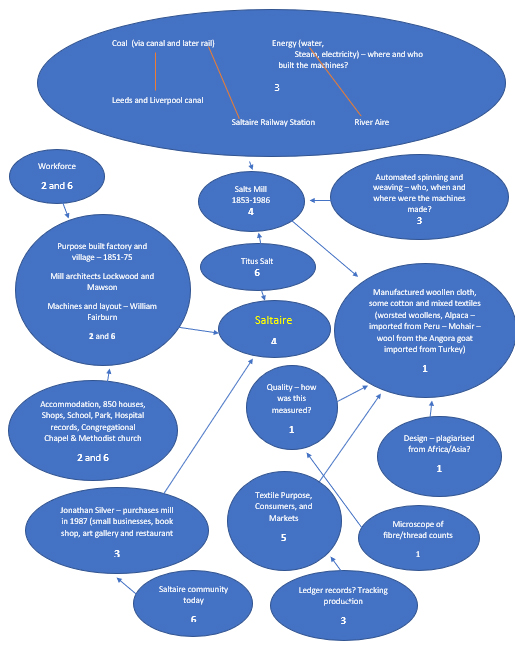

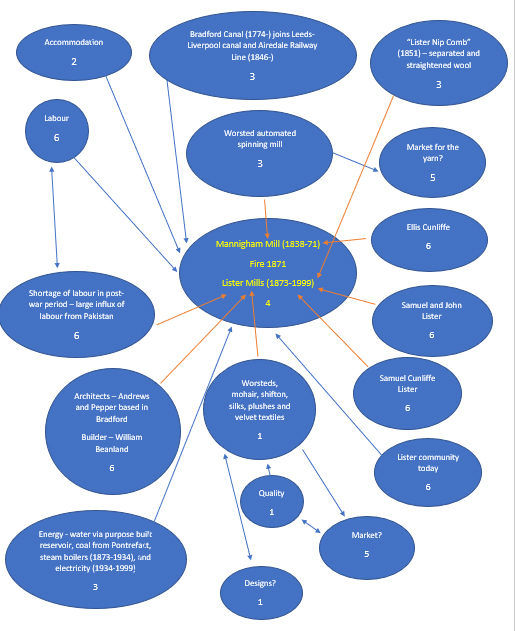

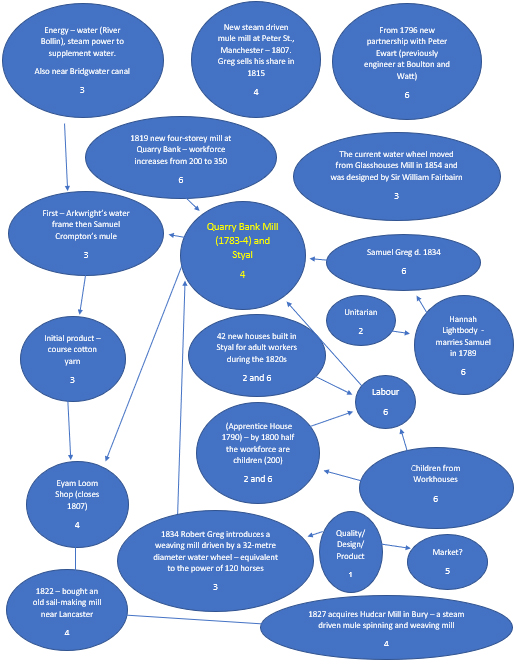

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221815/002In the following sections I propose six macro categories to encapsulate key potential areas of historical interest; we can start filling them up with micro studies from the three case studies (Figure 2). For example, in the case of the line diagrams I created for Salts Mill, Lister Mills and Quarry Bank Mill below you can easily see where such themes can be placed in the larger six categories (Figures 3, 4 and 5). These themes are not standalone and, as the diagrams demonstrate, link pertinent topics such as ‘Quality and Design’ with ‘Markets’, or ‘People’ with ‘Regions’. This approach will then allow us to do the same, first, with other partner institutions and then spreading the project’s tentacles further. Diverse textile collections can thus be interconnected via a consistent taxonomy and, where they don’t fit, new themes can emerge. It is crucial classification does not dictate the organisation of digital textile collections and remains malleable.

In this way digitisation will allow the smaller (microscopic) case studies to be linked to the larger (macroscopic) categories – and not get lost (Hitchcock, 2018).[23] Obviously, additional macro boxes can be created if and when needed. Having such searchable categories might eventually allow the user to, say, enter ‘Saltaire’ via any number of the taxonomy and find what they want (much like Discovery: National Archives – but with real content). For instance, questions could be asked such as ‘What was the purpose and market for Salts Mill fabrics (5)?’, ‘What was accommodation and welfare like (2)?’. Or a user could simply ‘search everything that has something to do with Saltaire’. Other questions might be, ‘I just want to know what the textile machine my mother operated was like in 1965?’, ‘What were the conditions like?’, ‘Who else worked there?’, ‘How much were they paid?’. Of course, searchable terms have their own problems, and the researcher must be aware of the words used in the contemporary context (Bressey, 2020). As Congruence Engine develops, new research terms will inevitably appear and iterative growth will be encouraged. The categories and approach developed here for the Textiles theme will also be pertinent to the other Congruence Engine themes of Energy and Communications. Below is a diagrammatic representation of the categories we might start with.

Six macro categories

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221815/003 [24]1. Quality and Design

Resources in this category might include: items that address the quality of the end fabric (warp and weft); microscope pictures of fibre (woollens, silk, linen, mixed cottons, cotton), thread counts and design; examples of imitation of foreign designs and fabric for the domestic market and variations of foreign designs/fabrics to penetrate overseas markets; sources such as John Styles (for global issues), Harris Museum and Art Gallery (for Asia and Europe) and Julie Halls and Allison Martino (for Africa)[25]; design books, designers, design shops (or evidence of in-house production). These can be scrutinised by instruments outlined in the opening text.

2. Accommodation and Welfare

Here there could be sources that reference types of housing for textile works; local amenities and provisions (shops and currency); education (the nature of subjects taught and location of schools and industrial institutes); health (factory doctors, hospitals, type of treatments, medicines); religious affiliations and churches; resources such as photographs, related artefacts, and written documentation.

3. Production, Technology and Costs

Resources that support research into the origin of the raw material – where did these come from, the Americas? Europe? Africa? Middle East? Asia? Australasia? or the UK? Evidence of tariffs, transport routes (ships, ports, canals, roads, railway, planes); sources of energy in production (human, animal, water, coal, town gas, electricity; energy transport routes – was coal delivered via canals, for example)? How long did obsolescent power systems remain? Machinery of production (hands, spindles, spinning wheels, automated spinning, automated weaving) and sources of machines and methods of transport, and did these require external skills (for example, a Boulton and Watt engineer) or in-house skills (for example, wheelwrights). How were refits carried out within the mill complex? What characterised the mill’s industrial ecosystem and the resources needed? For example, the engineering works to produce machines, chemical works, dye works, print works. Do new industries emerge out of this network? What was the mill constructed from? Was it from local materials or from specialised suppliers – such as the iron and/or steel framing used? How was fireproofing developed? What was the source of lighting and how did this change over time (natural light, oil, gas, electric)? What was the origin of labour – was it from Europe or Asia or local? How were the large capital costs of mill construction met, who were the financiers, how did this change through time?

4. Region

What were the areas of the textile industry in the UK? Resources here might cover, for example, woollen and mixed woollen textiles from Yorkshire, the West of England, East Anglia; cotton, linen and mixed cotton textiles from Lancashire, Derbyshire, Nottinghamshire, Northern Ireland and the Scottish Lowlands; silk from London (Spitalfields), East Anglia (Norwich), Kent (Canterbury), Suffolk (Sudbury) and Cheshire (Macclesfield, Congleton, Bollington, and Stockport). Information on specialised regions for specific textiles – for example, the Liverpool surrounding area for manufactured sailors clothing (Lambert, 2021).[26] Resources could also include mapping of working museum-mills/factories, aerial and ground photographs, written documentation.

5. Market

Were the markets domestic or abroad? What were the type and purpose of the textiles (clothing, curtains, carpet, bedding)? Places of the producer, merchant, buyer and consumer. How was distribution achieved – canal, road, river, train, sea or air?

6. People

Who were the owners of production, workers (pre-automation), workers (post-automation)? What was the source of labour: orphans, women, men, children, domestic or outside the UK? Insights into workers who migrated (nationally and internationally) to work in the textile industry – including gender breakdown, age, most frequent places of origin. Resources on the impact of migrant populations on mill towns; for example, the changing style of architecture in Little Germany in Bradford linked to arriving German immigrants. Architects, engineers, examples of architectural practices. Questions relating to their technical know-how, technical diffusion, origins, education, nationality, including links to the census. How long do textile workers persist in given areas? Resources could include photographs, pictures, videos, documentaries, written material.

Samuel Greg: a microstudy

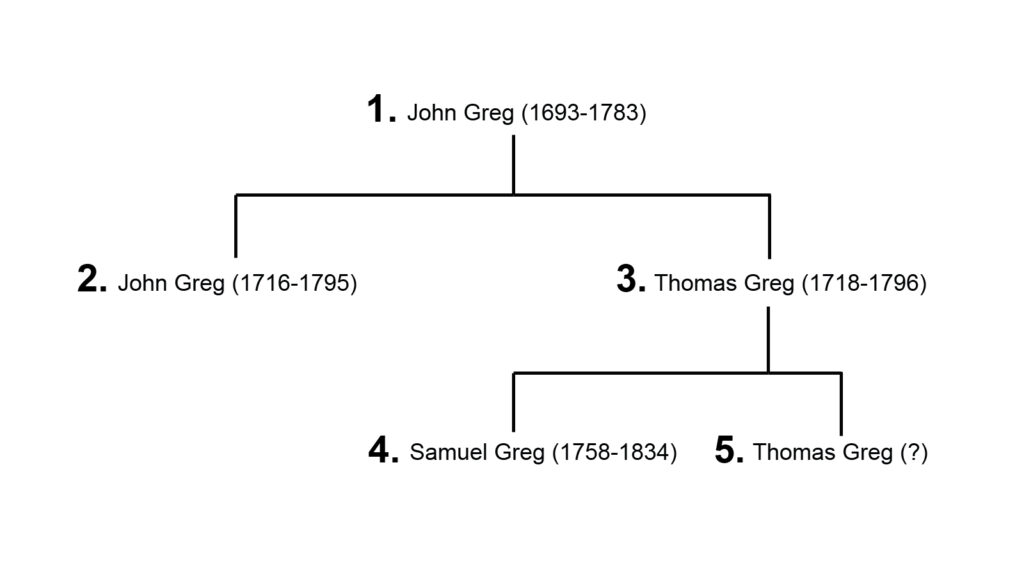

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221815/004The following detailed microstudy conveys the complexity of information radiating from the ‘people’ category within the third of the case studies above. Samuel Greg, owner of Quarry Bank Mill, is noted in Figure 5 (category 6). The study demonstrates how the pre-Samuel Greg history is an important component in understanding the roots to Quarry Bank Mill. It shows the power of connection suggested by the Congruence Engine approach, linking the mill history to Congruence Engine partners like the Northern Ireland collections, as well as related projects such as the Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery based at UCL. Indeed, much of the research for the microstudy draws upon the latter’s online source. Other digital collections referred to include ‘Plantation Records for Dominica, British West Indies’, University of Manchester; the University of Cambridge Digital Library; the Social Networks and Archival Context; Electric Scotland; Wikipedia; Dictionary of Irish Bibliography; The Spinning Project; and BBC Online articles. The following printed book provides some very useful genealogy of the Greg family: Michael James, From Smuggling to Cotton Kings: The Greg Story (James, 2010), and W H Crawford for the importance of linen yarn from Ulster to NW England (see his The Domestic Linen Industry in Ulster, Crawford, 2021). In Figure 6 relevant people are numbered, with further details listed chronologically below.

1. John Greg was a fervent Presbyterian born in the village of Ochiltree in Ayrshire, Scotland in 1693. He moved to Belfast in 1715. This part of Scotland was a stronghold for religious dissenters with many subsequently moving to Ulster from the early seventeenth century. With the Hanoverian, George I, coming to the throne in 1714 and the first Jacobite rebellion in 1715, John, with his wife Jane, fled to Ulster. In Belfast he became a wealthy merchant, ship owner and owner of lands in mainland America and the West Indies. From the late seventeenth century Belfast had become a major linen manufacturing centre nurtured by indigenous Irish and an array of transnational peoples. The relaxing of the Navigation Acts in 1731 enabled a flourishing trade in flax between Belfast and New York. John and Jane had two children – John Greg and Thomas Greg.

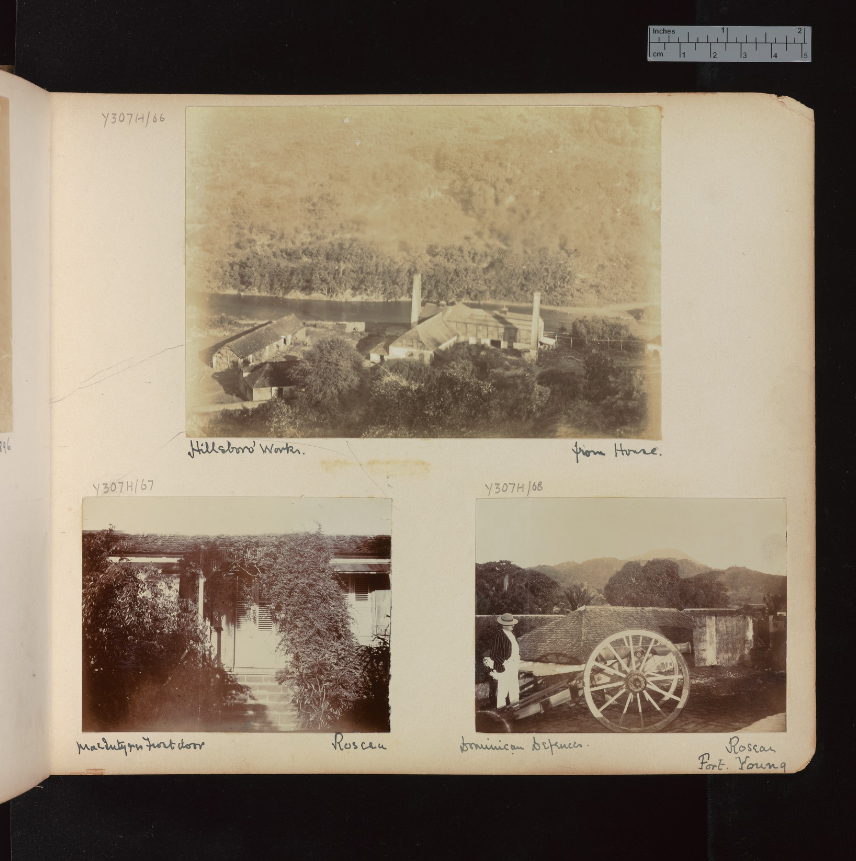

2. John Greg, the eldest son of John Greg, moved to the West Indies in 1765 and became the first government commissioner for the sale of land. He purchased two slave plantations: first, a 250-acres concern in Hertford (later sold),[27] and one in St Dominica called Hillsborough[28] that was 120 acres. He married Catherine Henderson (?–1819) who, in 1773, inherited a plantation called Cane Island in St Vincent. All were slave-based sugar plantations. Prior to his move to the West Indies, he had been in a partnership with John Torrans[29] in a company called Torrans, Greg and Pauag – trading with Charleston in South Carolina. They were major slave traders. John and Catherine had no children and left their plantations to Thomas and Samuel.

3. Thomas Greg was the younger son of John Greg. He traded in flax from British North America to Belfast. Thomas married Elizabeth Hyde (?) who was the daughter of the wealthy Belfast businessman, Samuel Hyde (d.1744) – originally from Lancashire. Samuel Hyde died soon after, and Thomas formed a company with his sister’s brother, John Hyde (?), in the firm of Leggs, Hyde and Co. – becoming Belfast’s largest sugar refiners and provisioners. Thomas subsequently joined forces with Waddell Cunningham (1729–1797)[30] – who worked in the linen and flaxseed trade in New York, British North America – and both formed another partnership in 1756, becoming the most successful traders in their field. Thomas and Waddell helped the funding of an improved river connection from the linen yarn producing region of Lisburn to Belfast (this is part of the Lagan canal, 1763–). In addition, they set up an early vitriol bleaching factory by the Lagan at Lisburn. They opened up a fishery in Donegal and Sligo to provide herring for slaves in the West Indies, while they also traded horses and mules to exchange for West Indian sugar and tobacco. Waddell married Margaret Hyde (?), sister of Elizabeth, Thomas’s wife. Cunningham was a vocal advocate for the formation of a Belfast Slave Company. Samuel Hyde’s son and brother of Elizabeth, Robert Hyde, remained in Lancashire and ran one of the largest fustian producing mills in Manchester with his partner Robert Hamilton (?) and subsequently his brother Nathaniel Hyde (?). The linen yarn for the warp of their fustian cloth was supplied by Thomas Greg. Thomas and Waddell purchased a slave plantation called Belfast[31] in a location adjoining his brother’s Hertford plantation in St Dominica – and thus probably managed by John Greg. Thomas and Elizabeth had 13 children – two of whom were Samuel Greg (1758–1834) and Thomas Greg (?–1832).

4. Thomas Greg sent Samuel Greg (1758–1834) over to England to work in a fustian textile mill belonging to his uncle Robert Hyde (1723–1782) and Robert Hamilton. It was one of the largest mills at the time in Manchester. He formed a close relationship with childless Robert.[32] In many ways the mill was complementary to his father’s trade in flax since the latter became Robert’s supplier. Interestingly, too, they relied on Thomas Greg and Waddell Cunningham for their supply of raw cotton from the Americas. Robert made Samuel a partner in his company and gave him £10,000 and the business upon his death (this was on the condition his subsequent partner, his brother Nathaniel Hyde (?) did not have a son). Upon the latter’s retirement, after his brother’s death, he sold John Middleton(?) and Samuel Greg his share in the warehouse stocks that they all jointly owned. This yielded Samuel Greg a later profit of £14,000. It is all this manufacturing experience and capital that made the building of Quarry Bank Mill possible (1783–1784). The rationale behind this project was simple: at this moment in time there was not enough cotton yarn for weavers. Consequently, Samuel realised there was a great profit to be had by building an Arkwright water-frame factory to spin such yarn. His first partner was John Massey (?) who died before the mill was completed and was replaced by Matthew Fawkner (?). The site chosen to build the factory was by the fast-flowing River Bollin in Styall (Cheshire). Its initial manufacture was coarse cotton yarn to supply their loom shop in Eyam (Derbyshire). By 1800 half the apprentices working at Quarry Bank were child orphans – initially from workhouses in London and then Liverpool and Manchester. Samuel met his wife, Hannah Lightbody, at The Chapel in Cross Street, Manchester. This was originally a Presbyterian Chapel but had become Unitarian by this time. Hannah was the daughter of a successful linen merchant.

5. Thomas Greg (?–1832) is also the son of Thomas Greg. Thomas the elder sent Thomas to England at the same time as Samuel. However, he went to London instead where he commenced a career as a marine insurance broker. His career soon took off and he became the broker/underwriter for his father and other notable merchants such as the Lyles, Batts and Cunningham’s – all religious dissenters based in Ireland. In England he worked for the Hydes, Philips and Hibberts of Manchester and the Rathbones (note the Rathbone box in the archive at Quarry Bank) and Lightbodies of Liverpool. He took on a Scottish partner called George Wood (d.1817) and by 1810 ‘Thomas Greg and Co.’ had made some £212,000. Earlier, in 1778, Greg had married Margaret Hibbert (1750–1808) but they had no children. The link with the Hibberts is interesting because they specialised in exporting finished cloth, including printed calicoes from Calcutta to places like West Africa, and the family had a strong stake in the slave trade. Margaret’s uncle, Thomas Hibbert (1710–1780),[33] was a slave factor operating from Kingston in Jamaica and exported products such as sugar and rum back to his kin in England. He was perfectly placed to purchase slave plantations that had gone under or had suffered financial losses – over the course of his career he held sixty plantations mortgaged to him; for example, in 1754 he gained his own 3,000-acre plantation. Thomas’s brother, Robert Hibbert (1717–1784), had 11 children including George Hibbert (b.1757–1837)[34] who became a leading City figure, and defended the slave trade as crucial to mercantile prosperity. Another son, Robert Hibbert (1769–1849), was also a slave factor and married to Elizabeth Jane Nembhard (1776–1853) – he owned the Georgia plantation in Hanover, Jamaica.[35] It is also worth noting that George Hibbert’s daughter, Caroline Hibbert (?), married her cousin Samuel Hibbert (1783–1867) – the son of Samuel Hibbert (1752–1786) – presumably the brother of Robert Hibbert – and Mary Greenhalgh (?).[36] No doubt Thomas Greg’s marine insurance company insured the Hibbert’s cargoes. Indeed, his business clearly played the main role in all the above family connected firms. Having no son of his own, Thomas Greg passed his business to Samuel Greg.

Congruence Engine is supported by AHRC grant AH/W003244/1.