Book review: Applied Science: Knowledge, Modernity, and Britain’s Public Realm by Robert Bud

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/252301

Abstract

Dr Robert Naylor reviews Applied Science: Knowledge, Modernity, and Britain’s Public Realm by Robert Bud.

Keywords

book review, Industrial revolution, Information Age, nineteenth century, science, Twentieth Century

The book follows a broadly chronological narrative, beginning in the early nineteenth century and ending at the beginning of the twenty-first. The introduction does a good job of defining and justifying the scope of the topic. ‘Applied science’ is indeed a slippery concept, and restricting the main narrative to the United Kingdom helps make the subject matter manageable. The introduction states the author’s claims that applied science was a concept that drove institutional development, shaped modernising social movements, and formed a basis for British industrial policy. Bud claims that the ‘history of the phrase and the concept behind it are inseparable’, stating that the use of the term helped refine the ideas it expressed. In effect, this does appear to restrict the scope of the book somewhat on a terminological basis, which may be dissatisfying to those who are interested in the broader epistemological layers and complexities of the topic. However, I personally take no issue with the terminologically informed scope – it provides an easy entryway to key venues where the concept was negotiated and means the audience does not become bogged down in extensive epistemological debates at the start of the book. The book is split into eight substantive chapters and three stages. The first three chapters form stage 1 – ‘Origins and Pedagogy in the Nineteenth Century’; the next three form stage 2 – ‘Research in the Early Twentieth Century’; and the last two chapters constitute the final stage – ‘After World War Two’.

The first chapter recounts the introduction of the phrase in English by the poet and philosopher Samuel Coleridge in the introduction to Encyclopaedia Metropolitina (1818), as well as its early propagation and utilisation. As it turns out, the term ‘applied science’ follows other scientific terms like ‘the big bang’ and ‘spooky action at a distance’ in being coined by someone who could be seen as a detractor. Coleridge’s ‘applied sciences’, heavily influenced by German thinking, denoted knowledge that depended on the empirical evidence of the external world, as opposed to the synthetic first principles of the mind that informed the ‘pure sciences’. Coleridge assigned a lower status to applied sciences as opposed to pure, and argued that any societal improvements induced by applied sciences needed to be rooted in older certainties, lest such revolutionary activity cause the collapse of civilisation. Encyclopaedia Metropolitina, published until 1845 under a series of editors, continued Coleridge’s usage of the term, and introduced the singular form of ‘applied science’. Despite applied science’s rather conservative birth, Bud also examines the influence of the French revolutionary science appliquée aux arts (science applied to the [practical] arts), the needs of new institutions such as King’s College London and the British Association for the Advancement of Science, as well as the scholarly entrepreneurship of the Scottish chemist J F W Johnston as he navigated the sensitivities of the farming community. The chapter concludes that by the 1840s the concept of applied science was both cultural and practical, providing a civilising influence on industrial practitioners as well as a material response to key national challenges.

The following chapter expands on the role of institutions, including government, in promoting the applied science concept, a theme that is carried on throughout the book. The Great Exhibition of 1851 stimulated and reflected new interest in explaining and maintaining Britain’s industrial predominance, and applied science became a culturally acceptable framing through which an ostensively laissez-faire government could support the training of engineers, providing an educational grounding without going so far as to encroach on proprietary knowledge or provide qualification for practical operations. Under the influence of (another) Scottish chemist Lyon Playfair, in 1853 the UK government set up the Department of Science and Art within the Board of Trade, which took over what became known as The Metropolitan School of Science Applied to Mining and the Arts. Playfair was also involved in the foundation of Dublin’s College of Science, which focused on applied sciences, and exported the Dublin model to Edinburgh. Playfair and others, having been disappointed by the British showings at the 1867 Paris Exposition, placed pressure on Parliament which launched an enquiry into the provision of ‘instruction in theoretical and applied science to the industrial classes’, leading to a significant rise in the usage of the term in the British press. Meanwhile, non-conformist industrialists founded colleges in industrial cities such as Manchester and Birmingham that divorced science and theological education, often with applied science as a guiding principle. In the chapter conclusion, Bud highlights how applied science was public rather than proprietary knowledge, an idea that holds much contemporary scholarly relevance, reminding me of John Krige’s recent work on the ongoing ‘chip war’ between the United States and China (Krige, 2024).

Bud follows this chapter with a much-needed discussion of the competing concept of ‘technology’, which Bud argues mainly entered English through the German term Technik. Industrialising slightly later than the British, Germans apparently had less concerns about proprietary knowledge, and therefore set up a number of Technische Hochschulen outside of universities, which encompassed theoretical and directly practical knowledge. Admirers in Britain, largely through private organisations and funding, set up a new system of examinations in science and technology for the industrial classes, leading to a new qualification system in 1873. Promoters of ‘technology’ still had to carefully navigate the British laissez-faire spirit, and technology was defined in terms of the application of science, although in practice the examinations reached into more directly practical industrial activity. In 1889 the government allowed local authorities to fund technical instruction, leading to the foundation of twelve ‘polytechnics’ in London (not to be confused with the later 1960s polytechnics). Increased feelings of technological inadequacy against Germany around the turn of the century led to the foundation or reorganising of more institutions, such as Manchester’s Municipal School of Technology (1900) and London’s Imperial College of Science and Technology (1907). However, when many science colleges applied to become universities around the same time, they had to prove that their education was broader than the technical, and applied science became a useful tool by which new universities could demonstrate their links to high culture and a heritage going back to Plato and Aristotle. The division between applied science and technology remained hotly contested throughout the interwar period, often institutionally heterogenous and reflective of class boundaries, the latter of which I feel could have been explored more fully in the book through some case studies.

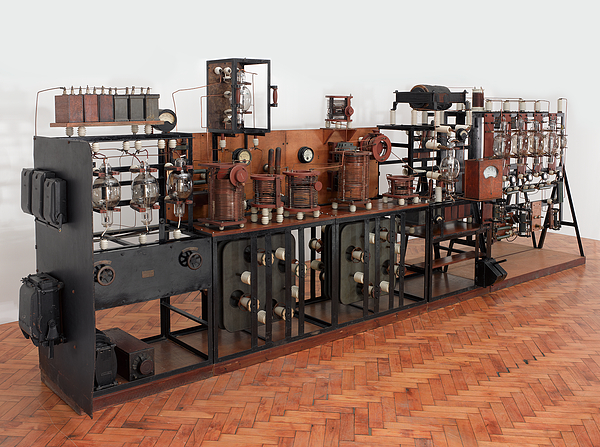

The second stage opens with a chapter on the lead-up to the First World War. Whilst many of the nineteenth-century narratives continued, applied science increasingly began to be seen through the scope of research and product development rather than just pedagogy. New products such as radios gave everyday meaning to research, and usage of ‘research’ in newspapers rapidly rose. Anxieties about international competition from Germany and the United States contributed to the foundation of both industrial and state-funded research laboratories, such as the Wellcome Physiological Research Laboratories (1894), the National Physical Laboratory (NPL, founded 1899), and the Imperial Institute (nationalised 1900). In response to increased calls for tariffs to combat foreign competition and promote imperial solidarity, the pro-free trade Liberal party turned to government-funded scientific research (carefully distanced from the market) as part of its alternative programme of national efficiency. Bud uses the NPL as his main case study, which was founded in order to standardise and verify constants and instruments in industry. From early on the NPL’s ambitions extended to applied science more generally, often against the headwinds of the Treasury and industrial scientists, and it gained funding partly by jumping on issues of military application such as shipping and aircraft, exciting topics that also made the NPL a favourite with the press. In this new environment, especially during and after the First World War, the relationship between applied and ‘pure’ science was continually renegotiated, with NPL administrators and government reports suggesting a continuity between pure and applied science, a closer bond that academic scientists came to accept with some reluctance. The hierarchy was disputed, with some academics claiming that applied science was wholly reliant on pure science and various leaders within industry and the NPL arguing for a more reciprocal and interdependent relationship.

The fifth, much longer, chapter focuses on new public and private bodies in the interwar period, especially the activities of the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research (DSIR). Advanced German wartime weapons had further demonstrated the importance of research as a military tool, and the military continued to be a substantial investor in research after the war concluded. Wartime experience honed new research laboratories in the Army, Navy and Air Force that were led primarily by scientists, echoing the NPL. The most consequential new body for the story of applied science, however, was DSIR, which was initially envisaged as an educational body but had its remit changed to ‘scientific and industrial research’ by a new Conservative government in 1915. DSIR, which ended up taking over the NPL and other research organisations, was overseen by an Advisory Council of eminent scientists that notably did not include industrialists, although the department remained aware of both scientific and industrial stakeholders as reflected by its annual reports. By 1926, DSIR was equating industrial research to applied scientific research, and later it promoted the idea that future prosperity was based on a mix of pure and applied scientific research, a model that suited laissez-faire governance as well as the interests of both pure and applied scientists. DSIR also provided matched funding for a number of industry-specific ‘research associations’ that attracted wide membership and were heralded in the 1930s press as a symbol of applied science’s success. However, continuing anxieties over government overreach into the commercial space posed challenges to DSIR’s model, with government criticising a lack of research ‘receiving mechanism’ in companies, who in turn complained that national laboratory research was too difficult to implement. Case studies are undertaken on the coal–oil energy transition and the development of better radios, demonstrating how applied science was also used to assure a better future to staff, shareholders and management.

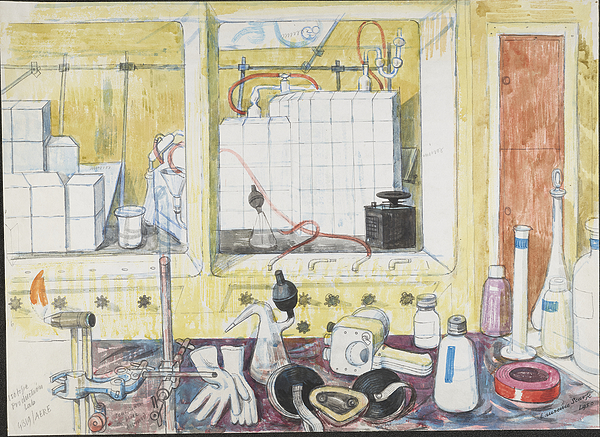

The stage closes with a chapter that focuses on applied science’s cultural resonances in the public realm during the interwar period. Many commentators linked applied science to ‘civilisation’ and the dizzying array of new everyday technologies that arrived during the period. For many, there was a congruence between modernity, applied science, and greater opportunities for women. However, ‘modern civilisation’ also had many critics, especially from within churches, who believed that science had caused untold suffering during the conflict and had atheistic tendencies. This new applied science-based civilisation came to be represented by the word ‘rationalisation’, which held connotations of scientific management of workforces, the fine balance of supply and demand, and the application of scientific research. Rationalisation was treated with suspicion by adherents to the free market, and was the subject of Aldous Huxley’s famous satire Brave New World. Increasingly, it was specifically ‘applied’ science that was the subject of anxiety, with ‘pure’ science being perceived as morally neutral. Whereas within government DSIR emphasised a mix of pure and applied science, in public it carefully promoted a separation in an attempt to sanitise itself from the negative connotations of dangerous applied science. In other venues, such as the Science Museum which opened in 1928, such negative connotations were actively combatted by the promotion of applied science’s wonderous products. Applied science was also a recurring theme of discussion in a number of radio series commissioned by the BBC science producer and former botanist Mary Adams in the 1930s. Overall, the chapter provides a good overview of how applied science was formulated in a rapidly developing media landscape.

The third stage of the book opens with a chapter focusing on the immediate postwar period. National expenditure on research increased significantly, and the advent of the nuclear age instigated both fears and hopes for modernity. Politicians and civil servants found that scientific accomplishment could be used to offset narratives of imperial decline, and there was a great demand for expanding the quantity and quality of higher technical education, leading to the expansion of universities and the upgrading of technical colleges. The 1945 Percy report described technology as both a science and an art, ascribing general principles to science and the application of these general principles to particular problems as art. Cold War research and US domination meant that much applied science came under a veil of secrecy, challenging old conventions of science research being openly published. Within such debates, applied science hovered at the boundary between publishable pure science and secret/proprietary technology. US ascendancy led to British narratives that the US exploited British pure science achievements through its primacy in applied science. Despite such concerns, it was not until the end of the 1950s that the organisation and structure of British science funding was challenged under the leadership of biologist Solly Zuckerman, whose committee reported five categories of research – pure basic research, objective basic research, applied (project) research, applied (operational) research, and development – which drew on both new American influence and a heritage of British applied science discourse. Zuckerman’s report recommended the dismantlement of DSIR and its replacement by several research councils, including one for applied research. In the event, however, the research councils founded in 1965 did not include one specifically for applied research. In the 20 years after 1945, government laboratories grew considerably, whereas industrial investment in research lagged behind other countries.

In his final substantive chapter Bud focuses on the interval between the 1960s and the beginning of the twenty-first century, when the usage of the term ‘applied science’ fell from vogue. In a new restricted funding environment, politicians began to stop believing that industry would convert applied science into radical societal improvements. In the 1950s and 60s, the British media and politicians emphasised a ‘second industrial revolution’ focused on technology and automation, leaving science as just another input. Traditional efforts to separate the public and private spheres were swept aside, eating away at applied science’s traditional institutional function. The new technology focus was institutionalised with the foundation of the Ministry of Technology by Harold Wilson’s government in 1964, which took over many of the government’s research centres. This institutional drive was reinforced by the foundation of 30 ‘polytechnics’, which kept distance between technological education and universities. Economists became more interested in the category of ‘innovation’, which placed emphasis on commercialisation and demand rather than the process of discovery. By the twenty-first century, ministers were discussing highly complex innovation processes where science was but a tiny part. Such changes were magnified by cuts to public science funding and a rising anxiety over the risks of science and technology, as well as the increased commercialisation of university research that continues today. The focus of research decisively swung from the public to the private sector, to such an extent that the traditional boundary between the public and private realms that sustained applied science ceased to exist.

In his introduction to the book, Bud states that it is necessary to study the development of related terms to ‘applied science’, and he does so, with discussions of ‘practical science’, ‘technology’ and ‘rationalisation’ to name a few. However, if I was to offer a critique, it would be that the book lacks any proper engagement with the concept of ‘operational research’, which became a mainstay of British industry during the postwar period, with its own societies, journals and historiography. Solly Zuckerman was a famous adherent – operational research’s scientific credentials seem quite clear – and the concept accompanied applied science as a complex intermediary between epistemological communities within science and industry. I feel that Maurice Kirby’s 2003 volume Operational Research in War and Peace helps enrich the story told in Applied Science, and the two should be read together (Kirby, 2003). Overall, the author should be congratulated on an excellent exploration of one of the most important framings of science in Britain, and I really got a sense of a coherent message about applied science taking form at the boundary between the proprietary and public spheres, a boundary that became blurred in the second half of the twentieth century. The concept of applied science helps illuminate how ideas around science more generally are negotiated – an important topic when scientific authority appears to be vulnerable to renegotiation and challenge. Late last year, during a tutorial, students on Manchester’s biology with science and society programme revealed to me that they believed that science is purely instrumental, having no meaningful existence beyond its services and products. If this tiny sample is in any way representative, it suggests that applied science, even if that precise terminology is no longer used, still has a future.