Review: Cabinet of Curiosities: How disability was kept in a box

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/150307

Keywords

Cabinet of Curiosities, disability, Emotion, engagement, engineering, Humour, Mat Fraser, Medical encounter, medicine, museums, research, science, Thalidomide

Review of Cabinet of Curiosities: How Disability was Kept in a Box

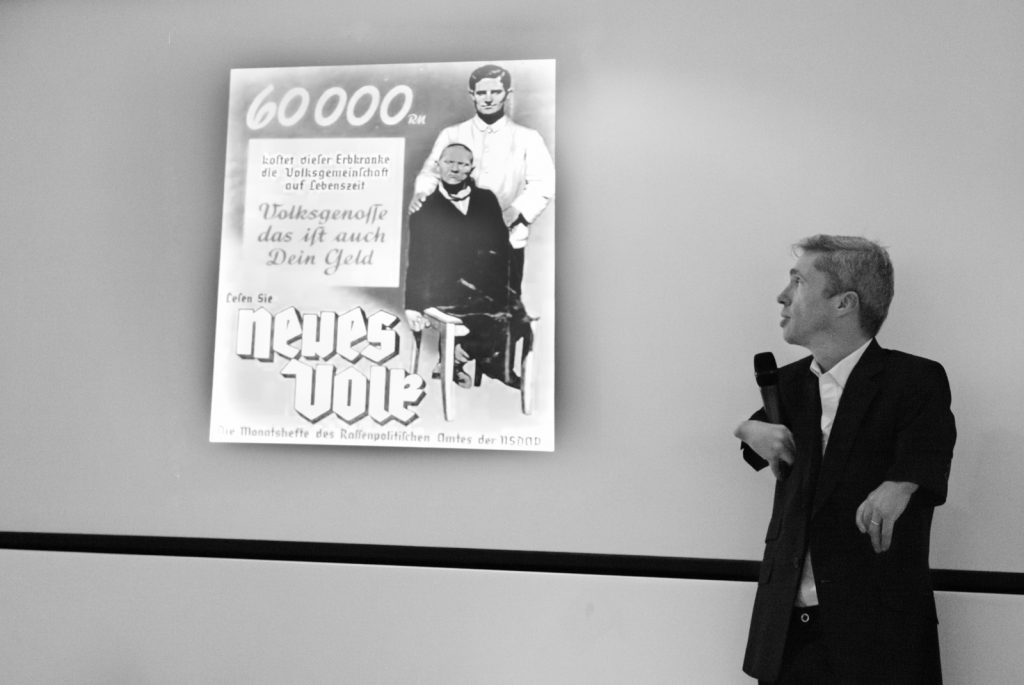

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/150307/001Cabinet of Curiosities is the public outcome of a research project funded by the Wellcome Trust into how museums of science and medicine interpret disability. The show was performed live at museum venues across the UK during 2014, and at the Museums Association Conference in Cardiff. Mat Fraser won the Observer Ethical Award for Arts and Culture in 2014 for the piece.

Personal, but based on research evidence, and combining myriad performance pieces within the format of a lecture, Cabinet of Curiosities offers a kaleidoscope of experiences and perspectives and, beyond the traditional role of a cabinet of curiosities, asks focused questions about some hard and conflicting truths.

Developed by actor and musician Mat Fraser, in collaboration with Jocelyn Dodd and Richard Sandell at the Research Centre for Museums and Galleries at the University of Leicester, and with the involvement of an authoritative array of museums of science and medicine, Cabinet of Curiosities is a one-man performance featuring an eclectic juxtaposition of academic lecture, autobiographical reflection, disability activism, punk, rap, social documentary, music hall pastiche and whimsy, to name but some of the modes that Mat Fraser nimbly guides his audience through.

It is tempting to try to define what this piece is, but that would lead us away from the more important question of why the collaborators have chosen to explore this complex subject in this way.

Mat Fraser begins with an explanation of his early concept for a comedy cabaret performance, which he swiftly abandoned with the realisation that the content he was researching was inherently ‘not funny’. Comedy is not lost as a mode of engagement however, as he compensates by building a comic theme around the prevailing absence of humour, emphasising the few jokes he can lever in throughout the 90-minute show (highlighting the 300 people with dwarfism living in the freak show village at Coney Island in the 1920s he says, ‘You can’t quite imagine the scale.’). Not a laugh a minute; but we begin to see that the different modes of presentation incorporated in this performance are critical to relieving tensions between the artist and the audience, and vital to conveying the complexity of emotions inherent in the content.

From the outset, the depth of research on which the performance is built is evident. Mat Fraser has worked with a carefully chosen group of museums of science or medicine to explore the history of how disability has been collected, catalogued, stored and displayed within their sphere. His outsider’s perspective on the museum process, and its impact both on people with disabilities and on the visiting public, is the starting point for the breathtaking juxtaposition of how things are currently done versus how they could (and should) be done.

A good example of the unthinking damage that has been done, and the converse potential that could be realised, is shown by the deconstruction of the concept of a ‘black box’. In museums, which are regarded as trustworthy and authoritative by the public, an interpreted ‘permanent’ display can be regarded as the final word and is often unchanging. This marries well with the scientific concept of a black box as ‘a concept which is defined, understood and no longer needs to be reconsidered’, akin to the definitive account given by an aeroplane’s black-box flight recorder. Contrast this, however, with the performing arts’ concept of a black box as ‘a space where you take risks with new ideas, hoping for some kind of change’. Not an approach typically associated with museums, but the message is clear: museums have much to gain from experimenting with other approaches and perspectives through which new interpretations would be created, giving greater validity and relevance.

Through this broader approach, the lecture content posits that museums have the opportunity to reverse the cultural apartheid that has seen people with disabilities included in museum displays only because of their disabilities, often in medical museums illustrating developments in engineering, science or medicine. The answer and the opportunity is to include disabled people by virtue of their other roles, as parents, children, professionals or members of the community, and ultimately to show how society is enriched by their inclusion and participation.

This vision could feel like a brave, new world, but we are acutely aware of the sense of Mat’s summing-up: this is a no-brainer, there is no justification for the fact that it did not happen yesterday, museums must get on and do it and make sure that it happens tomorrow.

It is a blunt message, so how is it made palatable? There are several means by which this is achieved.

Mat Fraser assumes the role of both lead dramatist and sympathetic narrator in the story, stepping back from the academic register of the research content to comment directly, and less formally, on the material he is sharing. He remains a well-informed, reasonable and reassuring guide for his audience, and alongside this he acknowledges the guilt and fear of medics and museums, and also shares his own anger and frustration as a participant in the story.

The project’s extensive research is demonstrated through the interleaved layers of more formal lecture. This evidence-based argument provides the objective stance which relieves the tension and emotion inherent in the opposing viewpoints explored in the piece. It builds to point the way to a self-evident conclusion about the overdue need for change.

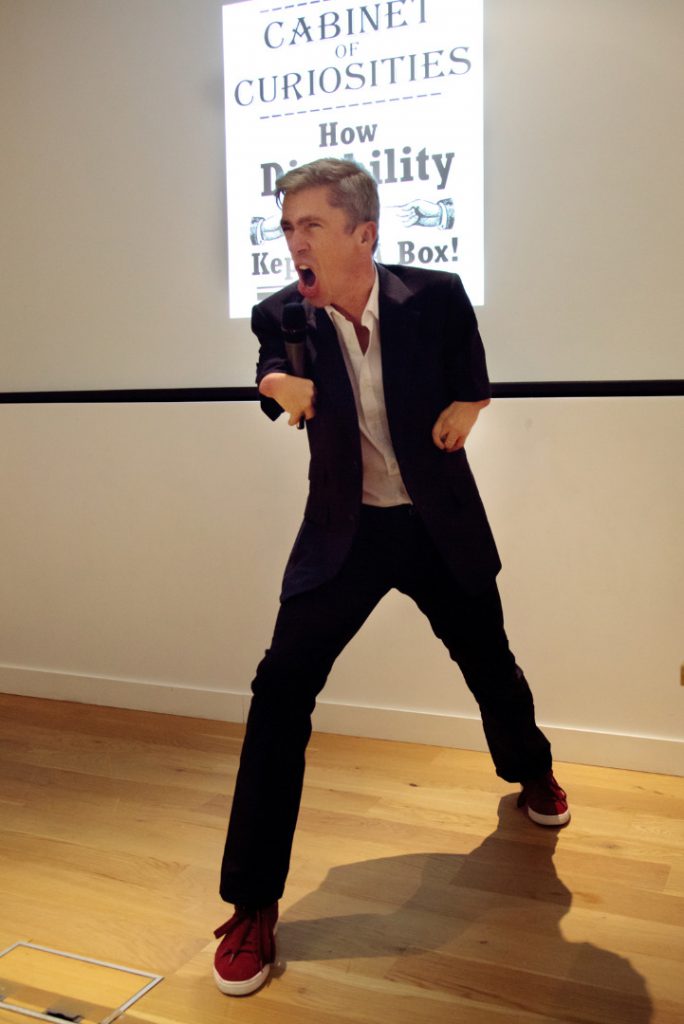

The strength of the different performance approaches is brought to bear on some of the more confrontational or contentious aspects of the content, for example the definitions of the medical, charity and social models of disability are set to music with an early-20th-century parodied voiceover and graphic style.

I found Mat’s autobiographical recollection of personal encounters with the medical profession some of the most striking and disturbing content in the piece, and the complexity of this proposition is expressed through punk. Mat recounts the medical profession’s guilty, and potentially salacious, fascination with his body, as a living specimen of the effects of the thalidomide drug on an unborn baby. He renders these combined memories into an aggressive punk thrash piece, which culminates in the incredible yell of ‘You have the bones of a DOG!’ – a direct quotation of a qualified doctor speaking to a patient affected by thalidomide.

This unique portrayal captures the dual perspective of patient and physician in the medical encounter and the rawness of emotion in both parties: the guilt, fear, anger and authority of the doctor faced with the embarrassment of the medical failure inherent in the thalidomide scandal, and the offensive, invasive and frightening impact on the patient. I defy a museum label or text to do justice to this complexity and, in this way, we see that the multiple modes of engagement are not an aside or a chaotic distraction but actually the real point of this show. Through performance art we can convey that which would be reduced or lost through words on a page or a censorious lecture.

Ultimately, this is the point of Cabinet of Curiosities. Research and evidence yes, but information, knowledge and learning do not equate to understanding. For that we need emotion. Messy and uncivilised, we are taught from an early age to control our emotions and to limit their place in learning. Cabinet of Curiosities shows that we need to give much more scope and validity to the emotional response, and open up museum practice to finding new modes of engaging the public (all of the public) with the objects that are chosen to represent our society.

Finding ways of successfully portraying the emotion with which objects and experiences are charged is the real goal and success of Cabinet of Curiosities. Some subjects demand and deserve emotional honesty and should not be divorced from that context. This is the accusation levelled at museums of science and medicine, which have unthinkingly colluded with the spheres they represent to perpetuate notions of what is normal and what is different. If interpretation is created without the involvement of those who have been systematically excluded from the mainstream, then museums will continue to reflect an unjust society instead of taking up the challenge of shaping a new social reality.

Towards the conclusion of the show, this point is made once more by overlaying a medical film with the oral testimony of Terry Wiles, who was also affected by the thalidomide drug. Terry is shown as a toddler standing on a table on prosthetic legs which make his natural limbs redundant. We see the medical definitions of his missing and residual limbs, and witness the proposed medical-technological solutions to his perceived problem.

Terry’s own voiceover in the present effectively puts the words of common sense into the mouth of a toddler. He felt unwieldy and unsafe, as though his personality had been changed and that nobody listened to his protests. This individual, social perspective completely changes our understanding of the prosthetic limbs shown. These are real artefacts in the Science Museum’s collections, which could easily be interpreted as an assistive innovation, but are more accurately summed up by Terry as ‘stupid’.

The performance begins and ends with haunting and questing music and photographic representations of people with disabilities, many from historic freak shows. By the end, our understanding of these people as individuals and of their decisions to take control of their lives or inability to do so because of socially imposed systems should have been transformed. The only correct response to the yearning optimism expressed in the final song is to act and make a change.