Connecting places and collections

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221811

Abstract

In aspiring to investigate diverse industrial and technological collections the Congruence Engine project highlights the fragmentation and loss of knowledge that often occurs when an industry or an individual workplace closes, or when a technology becomes obsolescent or redundant. Until relatively recently (often due to narrow institutional responsibilities and collecting policies) the heritage sector has had little ability to secure a holistic understanding of workplaces and the inter-connectedness of people, places, technology, objects and their associated records.

The Historic England Archive[1], which is essentially a place-based collection, may be unfamiliar to many in the museum sector and academia. This paper introduces its archive collections that relate to industry and technology, describes their evolution through past recording and collecting policies and discusses how they might be used to further a deeper contextualisation of museum objects. A case study of recent work at the Science Museum to secure the historical legacy of post-war power stations follows. It describes the processes and challenges involved in collecting large industrial heritage objects and illustrates how closer working relationships between heritage institutions might ensure that a more rounded response is made to the loss of obsolescent industries, plant and technologies.[2]

Keywords

air photography, archives, Congruence Engine, Historic England, historic environment, industrial heritage, power stations, Science Museum

Introduction

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/The historic fragmentation and loss of knowledge highlighted by the Congruence Engine project remains a familiar experience for contemporary heritage professionals confronted with the closure of modern industries and the loss of outmoded technologies. Even in the most favourable circumstances, for most twentieth-century industries the point of closure sees the living entity of an industrial enterprise quickly reduced to a fossil assemblage of vacant structures, artefacts, documents, photographs and people’s memories.

Traditional academic and community researchers and those professionally employed in the historic environment sector, museums and archives, may differ in both aims and resources. Academic researchers are often reliant on records created by government, such as Census returns or the chance survival of commercial and personal records, to discover more about places of industry. Those working for publicly funded heritage organisations often have responsibility for influencing what is collected in the first place – which historic structures are protected, which objects are preserved in museums, or which records, photographs and films are accepted into archives for the use of future researchers. In practice diverse individuals, community groups and professionals often come together to preserve valuable industrial heritage. Redcar steelworks provides a recent example. Here the 1970s steel works went into liquidation in 2015 and was being demolished at the time of writing. Although future plans for the site preclude any retention of structures, the works’ importance to the local area’s heritage was recognised through the Teesworks Heritage Taskforce, which included a local politician, arts leader, former steel industry employees and a local steel historian. Through the work of this group (in consultation with Historic England) a record of the site’s structures was commissioned, and artefacts and archives were rescued.[3] Before demolition Historic England were also able to undertake professional and aerial and ground photography. This kind of collaboration suggests a model for the future identification and preservation of important industrial heritage sites and artefacts.

This article will briefly explore the origins of the Historic England Archive and its unique characteristics as a repository of historic government records of its built estate, including architectural drawings and photographs. Other parts of the archive include aerial photographs dating from the 1920s to the present and capture the results of in-house research. This includes, for example, the architecture of the textile industry including a large quantity of photographs. The second part of this article provides a short account of the challenges of securing a historical record, archives and artefacts from recently closed coal- and oil-fired power stations. This case study brings the perspective, processes and practical constraints of the museum profession to the fore and suggests a collaborative way forward.

The Historic England Archive

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221811/002The Historic England Archive is housed in the former Great Western Railway drawing offices in Swindon, with most of the primary archival material stored in purpose-built environmentally controlled archive stores. To refer to it as a singular archive masks the complexity of its collections, why they were created, how they were acquired, and how they may be searched and accessed. Dispersed and structurally disparate, this material is ripe for exploration and collaboration around place, industry and practice and provides a rich resource for Congruence Engine research and beyond.

The collection originates with the records of the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments (England) (RCHME). This was established in 1908, but the original royal warrant effectively confined its activities to monuments constructed before the industrial revolution. This warrant commanded the Commission to ‘make an inventory of the Ancient and Historical Monuments and Constructions connected with, or illustrative of, the contemporary culture, civilization and condition of life of the people in England excluding Monmouthshire, from the earliest times to the year 1700’ (RCHME, 1911, p xi).[4] Another important constituent archive was that of the National Building Record (NBR), founded during the Second World War in 1941, whose main task was to acquire records of the country’s historic building stock that might be threatened by enemy action. The NBR carried out its mission by acquiring images and other material from a variety of sources as well as taking its own photographs of bomb-damaged areas. If resources allowed, photographs were also taken of the areas that might be threatened by future air raids (RCHME, 1991, pp 2–22).

In 1963 responsibility for the work of the NBR was transferred to RCHME. The 1960s also saw a loosening of the 1700 cut-off date and the beginnings of work by in-house photographers to record industrial topics, including the town of Macclesfield (RCHME, 1991, p 40). One of the most significant collections acquired at this time was that of the Bedford Lemere commercial architectural photographic company, which was active from the late nineteenth century until the mid twentieth century. This collection covers a wide range of subjects including factories, country houses, ecclesiastical buildings, municipal buildings, ship interiors and much more. Many company commissions illustrated newly completed or recently refurbished buildings.

As was typical of contemporary architectural photography, it was rare for these images to include people; in some they appear to add a sense of scale, although several images do apparently show genuine views of the world of work and its messiness.

Another remarkable collection is that of George Watkins, a heating engineer by profession, who from the 1930s to the 1970s toured the country photographing stationary steam engines. His work illustrates the importance of practical fieldwork and his images are often the only records of the machinery produced by some manufacturers. The work of John Gay (1909–99), a German émigré with an outsider’s eye, captured the atmosphere of mid twentieth century England, often depicting now vanished industrial scenes.

The acquisition of collections continues and recently around 10,000 images created by the John Laing construction company have been digitised and made available online.[5]

A public record

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221811/003Some of the current functions of Historic England were previously embedded within large and now defunct government departments, including the Ministry of Works, which was responsible for the infrastructure of the state, including defence sites, courts, offices, technical and development research facilities and the General Post Office. These close associations with central government have bequeathed the Historic England collection many official drawings and photographs giving it a unique character. A particularly important transfer of records took place in the early 1990s with the disbandment of the Property Services Agency when tens of thousands of drawings and photographs were transferred to the archive. This collection ranges from Victorian drawings of defence sites to 1980s photographs of newly completed government buildings. While the organisation’s policy and administrative records went to The National Archives, the records held by Historic England represent the most significant visual archive of the architecture of the British state. Much of the collection still awaits detailed cataloguing including adding metadata to packets of negatives that may only have high level catalogue entries. For the Congruence Engine these government records will be of special interest to the Communications theme with drawings and photographs of post offices and other civil and defence related communications structures.

In-house research

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221811/004The Archive is also the main repository for the results of investigations undertaken by in-house research staff. This includes records created by staff since 1908, although beyond the published county inventories few early documents survive. The late 1970s marked a distinct change of direction for the Commission as resources were moved away from county inventories to area and thematic-based studies. Another important development was the appointment of Angus Buchanan as a Commissioner with expertise in the history of technology and industrial archaeology. This was shortly followed in 1981 by acquisition of the Industrial Monuments Survey, which had previously been funded by the Directorate of Ancient Monuments and History Buildings of the Department of the Environment. The associated dedicated post to maintain this record was also transferred to RCHME (Falconer and Thornes, 1986, p 26).

This growing interest in industrial themes was marked by increasing numbers of projects addressing related topics, often produced in conjunction with local partners. These frequently included derelict but clearly historic places whose future in the late 1970s was in the balance and far from assured. Reflecting RCHME’s responsibilities, the primary motivation was for an architectural record but nevertheless the surveys were critical in establishing the significance of these places and their subsequent reuse. In Manchester a study was undertaken of Liverpool Road Station (Fitzgerald, 1980), now the home of the Science and Industry Museum. In Liverpool the historic dock buildings were surveyed (Ritchie-Noakes, 1984). Known today as the Royal Albert Dock, the Liverpool waterfront represents one of the largest heritage-led regeneration schemes in the country. The integration of industrial expertise with the Commission’s specialist photographers and buildings investigators (and later archaeological recording teams) brought new perspectives to the analysis of industrial buildings. The narratives of the country’s industrial past were greatly extended by interrogating the evidential value of buildings and sites to unravel their construction techniques, alterations, phasing and the organisation of machinery.

Concern about the pressures posed by rapid change was a common thread running through many of the Commission’s programmes. In the early 1980s it was recognised that challenges from the global market and the economic recession were leading to the widespread closure and loss of textile mills. In England these represent a unique resource exemplifying a type of building whose evolution may largely be illustrated in a single country. Yet recording was still influenced by the provisions of the royal warrant with its focus on recording monuments. The initial emphasis was therefore on the physical fabric of the buildings and although the prime movers – waterwheels and steam engines – were photographed, less consideration was given to the production machinery. Likewise, the social aspects of the industry revealed through the building fabric were rarely considered and contemporary photography continued to follow traditional architecture practice and was largely people-less. In the late 1980s three areas – West Yorkshire, Manchester and East Cheshire – were selected for study, with substantial monographs produced for all the study areas (Goodhall and Giles, 1992; Williams and Farnie, 1992; Calladine and Fricker, 1993). However, as with any source the context in which these archives were created needs to be appreciated. Again, the surveys echoed RCHME’s main concern of producing an architectural record, in this case of the most obvious manifestation of the textile industry: its mills. In later decades, when an investigation team returned to Bradford, the emphasis was on the places and communities that had grown up around the mills of Manningham (Taylor and Gibson, 2010). In this period where sites, buildings and areas have been the subject of detailed research there will often be substantial supporting photographic archives, research notes and source material.

Aerial photography

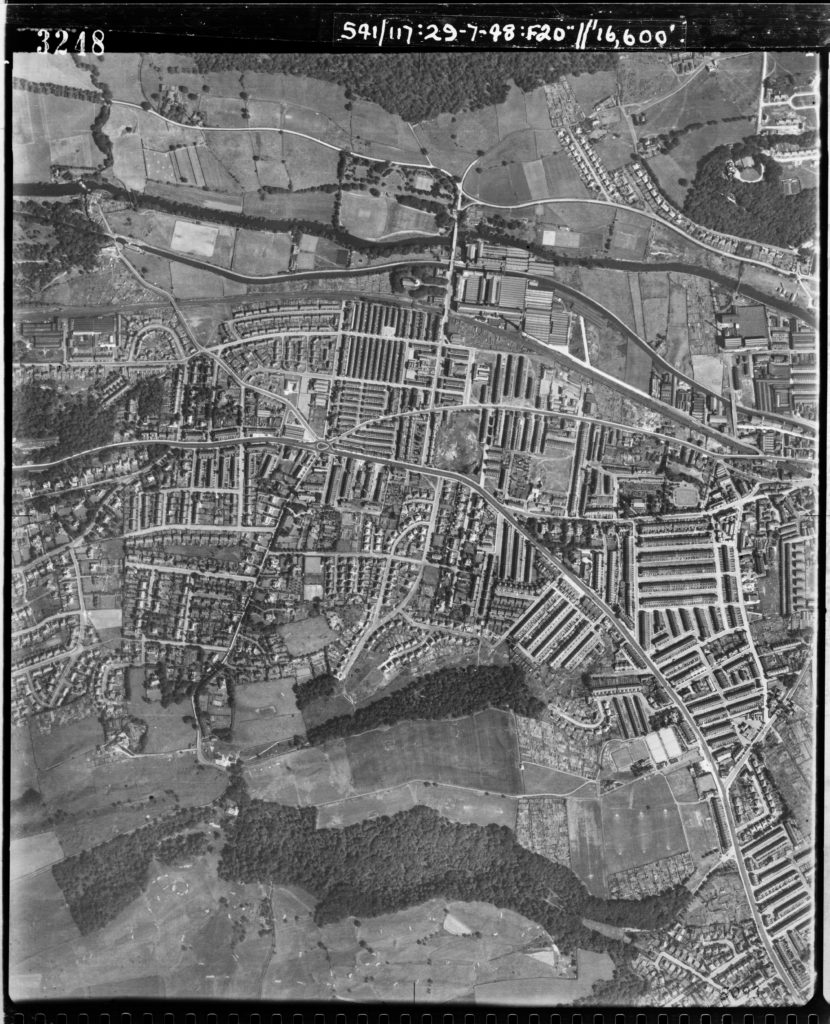

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221811/005Another important resource for the study of technology and industry and its wider urban and landscape contexts are Historic England’s collections of historic air photography. The aerial photograph collection was established by RCHME in 1965 and grew substantially in the 1980s when the Department of the Environment transferred its collection of vertical air photography of the country taken by the Royal Air Force after the Second World War.

This was supplemented in 1991 by the acquisition of the Ordnance Survey air photography that had been taken for mapping purposes since 1951. Also, in the early 1990s, images taken by Meridian Air Maps were acquired after the company went into liquidation. Another important commercial collection was created by Aerofilms Limited from the company’s foundation in 1919 until 2006; a year later it was acquired by a consortium of the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland, English Heritage and the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales. The older images, taken between 1919 and 1953, are available on the Britain from Above website. These pictures are of special interest as for many industrial locations they often provide the only readily accessible contemporary photographic images.[6] An important part of Aerofilms’ business was taking photos commissioned by commercial companies, or to offer to businesses speculatively.

Other aerial views were taken for the purpose of producing postcards. Today, the archive is a remarkable record of early-twentieth-century Britain, often providing the only readily available images of works and factories set within their local neighbourhoods. Other smaller collections of Historic England aerial photographs include German air force target imagery, often with associated annotated target maps, and allied wartime M-series low level photography.

In addition to collections acquired from other bodies from 1967, RCHME began to take low-level oblique photographs itself, although for the first few decades this was largely restricted to archaeological field monuments and crop marks. From the late 1980s aerial reconnaissance was extended to documenting building complexes and their local environs.

Around 400,000 digital images of recent reconnaissance photography and a selection of digitised historic images may be viewed on the Air Photo Explorer website, while around a further six million aerial images await digitisation.[7]

The historic environment and connected collections

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221811/006The professional management of the historic environment relies on comprehensive and accurate knowledge of the locations of historic landscapes, existing buildings and archaeological traces of abandoned or demolished structures. To underpin this management work local authorities have been developing historic environment records over the past decades. However, many of these records have been based on the former Ordnance Survey Archaeological Divisions record cards, which contain very few building records and even fewer records of more recent industrial structures.

Underpinning many decisions about the future of the physical traces of historic industrial buildings are assessments of their significance and value. As commissioned research by TaNC and the AHRC has shown, most professional and public researchers generally use a restricted range of familiar archival resources and contacts to explore topics of interest (The Audience Agency/Culture 24, 2022, p 2). This is also true in the historic environment sector, and especially so where research is constrained by commercial or casework deadlines. Researchers generally find that familiar resources, such as historic environment records, air photography, map regression and Google, will provide adequate information, perhaps calculating that under time pressure exploring further databases could yield diminishing returns. The intention of the Congruence Engine to create methods and tools to search across multiple unfamiliar databases offers the possibilities of strengthening cases for protection or deepening the understanding of industrial places.

Few industries operate in isolation; all require the support of machinery and equipment producers, processors, suppliers of raw materials and, in the case of the textile industries, manufacturers to produce finished goods. The skills in these supporting industries may then give rise to new industrial opportunities and enterprises. In Bradford during the First World War, for example, the coal tar dye industry that developed to supply the textile trade was quickly adapted to supply high explosives. This was a modification that had fatal consequences at the Low Moor works where 34 lives were lost during the production of picric acid, also known as Lyddite (Earnshaw, 1990, p 29). As links between databases are improved, we will be able to develop a greater understanding of the ecosystem of industries, and the skills and knowledge that are necessary in an area or country before a specific industry can become established or regarded as mature.

The Congruence Engine offers the museum sector the possibility of presenting hitherto displaced technological objects in the work and social spaces in which they were used. In many cases the close relationships between structures, manufacturing operations and machinery were reflected in the flow of materials and mechanisms for transferring power. Social spaces may be defined within workplaces by areas through which only certain individuals or groups can pass, perhaps expressed by a projecting window in a manager’s office permitting the local area to be readily monitored. Beyond the individual work position, a characteristic of many large twentieth century workplaces was the growth of communal spaces including canteens, changing and welfare rooms, and even sports facilities. Workplaces also generated the creation of new places, from the most basic shared living quarters for upland miners to complex urban conurbations.

Linking collections also offers opportunities to develop richer biographies of machines and other objects by forging links with other workplaces. To historians of technology the ability to link diverse records presents the possibility of understanding the diffusion of technologies and can answer questions about the distribution of building types. Does the use of a type of machine result in the construction of comparable buildings? Are these in turn influenced by local building traditions or perhaps by local regimes of work? Across Europe, Britain’s – and in particular Manchester’s – pre-eminence in textile production and machinery manufacture was widely acknowledged and copied. In Tampere, Finland and Leipzig, Germany, industrial quarters with tall textile mills developed a Mancunian character. In Ghent, Belgium, the Museum of Industry is housed in an iron-framed building constructed in 1905 and described as being in a Manchester style with a distinctive sawtooth, or north light, roof to admit light. Its extensive machinery textile collection is a testament to the dominance of textile machinery manufacturers in the northwest of England.

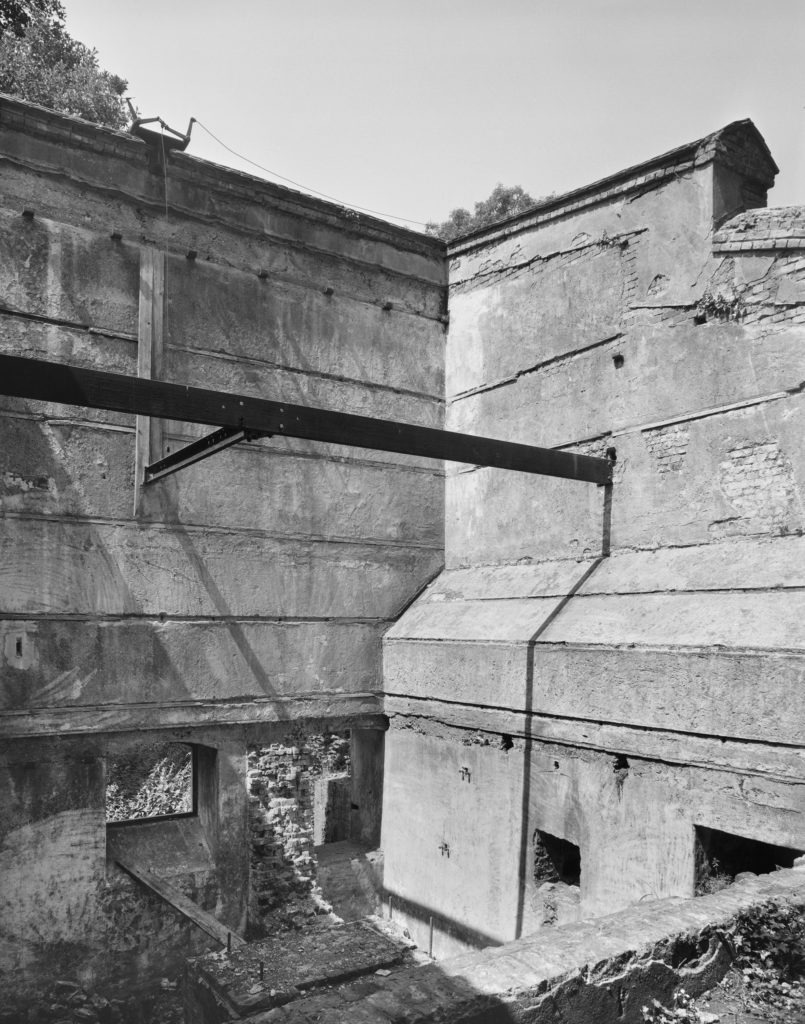

The transfer of complex technologies usually requires more than the simple sale of machinery or equipment – intangible knowledge of its operation and idiosyncrasies is also often required. The first author’s study of the Chilworth gunpowder works in Surrey in the 1880s is a good example of the importance of field observations and the serendipity of research to unravel a story of international technology transfer. The company was acquired by a consortium, including German manufacturers, to produce patent gunpowder using rye straw. At Chilworth rolled steel channels survive within a ruined gunpowder mill stamped ‘BURBACH’, clearly identifying its German origin and incidentally providing a very early surviving example of a steel beam in England.

By chance a Grusonwerks, Buchau-Madgeburg, trade catalogue held by the Hagley Museum and Library, Wilmington, Delaware, confirmed the installation of steel incorporating mills at Chilworth, and in the catalogue a drawing documents the position of mounting bolt holes which matched those seen on the beams at Chilworth.[8] Here detailed knowledge about the manufacturing process was safeguarded through the appointment of a German manager supported by a handful of German foremen, the language barrier perhaps adding a further layer of mystique about the process (Cocroft et al, 2005).

Debate within the archaeological profession, and by extension among historians of building history, has questioned the relevance of an archaeological material culture approach to researching the recent industrial past (Belford, 2014, pp 3–14). Despite an apparent abundance of secondary sources, there are many reasons why archaeological fieldwork is undertaken on relatively recent remains. It may be carried out prior to public display, as part of a community archaeology project, as academic research or, most commonly, in advance of redevelopment, where little or nothing may survive of previous activities. Ideally, all fieldwork will be guided by research questions that extend our understanding beyond what is known from other sources, although in many instances site archives will be lost or held in inaccessible private business archives. Easier access to archives and museum collections assists in identifying knowledge gaps and sharpening research questions to ensure archaeological methods are applied in areas where they can best contribute to new knowledge. For other groups of researchers, including local community and special interest groups and individuals, linked archives offer a pathway into perhaps previously closed places and contextual knowledge.

Working-class histories

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221811/007Place, or the physical context of an object or structure (which may range from a findspot of a single artefact to a site, building or more extensive urban or rural area) is the fundamental building block of archaeological knowledge and management of the historic environment. Research into current users of archive and museum websites also reveals that places and people are amongst the most popular search terms, allowing enquirers to connect with topics and themes personal to them (The Audience Agency/Culture24, 2022, pp 27, 49). Beyond the professional heritage sector many local groups and individuals have a strong interest in the history of their area and family ancestry.[9] Many working-class histories have yet to be written and the ability to readily connect people to the places where they worked, the machines and equipment they used, and the objects they produced will both bring a greater depth to their searches. A strength of a concept such as the Congruence Engine is its facility to enable chance discoveries taking searchers into new topics and allowing them to make unexpected connections.

As also noted by the TaNC/AHRC report on the needs of future researchers, place as represented by the historic environment is at the heart of many government policies, including inclusive growth, levelling up, regeneration, health and well-being and place making (The Audience Agency/Culture24, 2022, p 46). Historic England is active in all these areas and is leading a major initiative to promote urban regeneration in the north of England and elsewhere through the adaptation of former textile mills.

A good example of a former mill at the heart of its community is the Islington Mill, Salford, a six-storey Georgian cotton mill that has been regenerated as an arts venue.[10] Here, the historical and communal values of the building are an important part of project’s ethos. They inspire artistic responses: for example, the project Place in the Community reached out to people who had worked in the building and other residents to understand how they valued the building. Energy and communications related structures are more challenging to reuse due to their more specialised forms, although the most significant sites may be assessed for protection. Where retention is unlikely documentation strategies may be the most appropriate response, with complementary work securing building records, archives, artefacts and the intangible memories of work.

Power stations

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221811/008One more recent area of work concerns the recording and preservation of the physical heritage of power station staff, the buildings and workspaces, the machinery that staff used and the skills and practices they embodied. From the early decades of electricity generation there has been a cycle of construction and loss as plants reached the end of their design life or became obsolete as more efficient and less environmentally damaging energy-generating machinery became available. The historical legacies of modern industries are particularly vulnerable to loss at the point of closure, since securing a historical legacy may be low down on local agendas when faced with job losses and the desire to remediate and clear sites for new uses. In some instances, local authorities may be able to ask for records to be created prior to demolition, but this will often only encompass the built fabric of a place. Also, in many cases the absence of contextual studies means that the historical significance of places and objects can be obscure.

In some cases, such as Lots Road, Chelsea and Bankside, London (now Tate Modern), the buildings that sheltered the plant have been more enduring. Until recently there has been little consideration of the historic interest of outdated power plants: most have been cleared without record with at best the retention of a few objects as at Ironbridge A station, where several objects passed to the Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust.

Nuclear power stations

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221811/009During the early twenty-first century the last of the Magnox nuclear power stations entered their decommissioning phases. These sites and associated production and research facilities are owned by the Nuclear Decommissioning Authority (NDA), a public body and as such subject to the Public Records Act. In comparison to the privately owned conventional stations this will ensure that a careful selection of the industry’s records will be preserved and made accessible, in this instance at Nucleus, a purpose-built archive at Wick, Caithness.[11] It also provides a good example of various institutions sponsored by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, including Historic England, the Science Museum Group and The National Archives, along with colleagues from Wales and Scotland working together with the NDA to discuss retention policies. Through separate negotiations the Science Museum Group and the National Museum of Scotland secured the recovery of control desks from the Dounreay Nuclear Power Development Establishment. In this highly regulated industry strong costed business cases need to be made both for the retention of archives and the securing of objects from tightly controlled locations. This work highlighted that documents and objects relating to the social history of these places can be particularly vulnerable to loss, although local initiatives may ensure representative examples are collected. For many nuclear sites current guidance by The National Archives emphasises the importance of strategic, policy and technological material, which may include technical drawings, films and photographs.[12] Records of, for example, sports and social clubs, or company newsletters and magazines, will rarely meet national selection criteria. In such cases material along with objects might be deposited with local museums, as has happened at Caithness Horizons Museum and Art Gallery, Thurso and the Devil’s Porridge Museum, Eastriggs, Dumfries and Galloway.

Oil- and coal-fired power stations

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221811/010Over the last decade or so the majority of large oil- and coal-fired mega power stations inaugurated in the 1960s by the then state-owned Central Electricity Generating Board have come to end of their planned operating lives – a process hastened by stricter environmental controls and the government’s intention to close all coal-fired stations by 2024. Historic England has been working on a programme to record these stations in their landscapes by low level air photography and ground photography.

Guidance has also been provided on the collection of archives and artefacts and the criteria that might be used to select material (Historic England, 2016). The design of post-war power stations reflects an increasingly close collaboration between engineers and architects with an intimate relation between machine and structure. However, the collection of ‘big stuff’ is a long-standing challenge for science and technology museums often resulting in the selection of a part or a machine to represent the whole (referred to as a ‘synecdoche’ by Alberti et al, 2018, p 418). How can power stations be presented not only to characterise a given technology, but also explain the built and social context in which it was designed, manufactured and operated? These are the questions addressed in the case study in the next section of the paper. Written by a Science Museum curator, Ben Russell, who worked in parallel with Historic England’s recording work to acquire parts of Cottam power station, it explores from the Museum perspective the motivations, challenges and decision-making involved in collecting ‘Big Stuff’.

Case study: collecting Cottam power station

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221811/011While Historic England was working with the power company EDF to secure a record of its power stations at Cottam and West Burton, Nottinghamshire, the Science Museum was exploring the possible acquisition of artefacts from these sites. This case study describes the thinking behind the selections.

A recurring logistical challenge for the Science Museum – indeed, for any museum – is how to represent in physical form projects which may be on a gigantic scale. Making physically large acquisitions can place considerable demands on an organisation in terms of the planning, logistics and the long-term storage capabilities required. Nonetheless, large objects can play a powerful part in fulfilling the museum’s role, defined for the Science Museum as ‘making sense of the science which shapes our lives, helping create a scientifically literate society and inspiring the next generation’.[13] This case study will take the recent acquisition of a complete unit control desk from EDF’s Cottam power station to explore this complex matter.

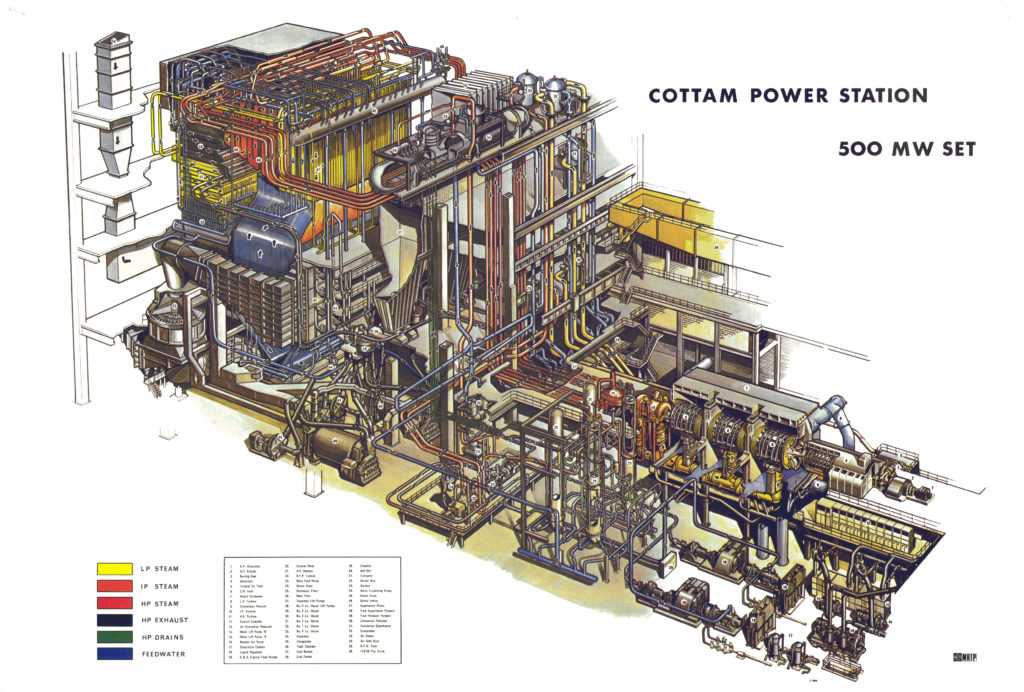

Collecting power

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221811/012The Science Museum has had a long-standing interest in industrial prime movers, with the East Hall and Making the Modern World galleries illustrating the evolution of steam power from the atmospheric engine to the steam turbine. The apogee of steam power in the UK comprises the enormous coal-fired generating units of 500MW capacity (later increased to 660MW) constructed under the auspices of the Central Electricity Generating Board (CEGB) between 1958 and 1990. Forty-nine such units were housed in a series of fourteen power stations christened ‘Hinton’s Heavies’, after engineer Sir Christopher Hinton, the CEGB’s first chairman. The ‘Heavies’ lived up to their name with the gigantic scale of their construction. Jonathan Clarke has summed up the CEGB’s achievement in building them thus:

It is perhaps fitting that what was the largest state-funded body, with the largest budget outside of Whitehall, should have produced the biggest monuments, and, as the largest patron of landscape architecture, with a nationwide ‘supergrid’ of transmission infrastructure, has left its mark on the landscape in a way only exceeded by road-building’ (Clarke 2015, p 7).

For fifty years these plants, each individually able to cover much of central London, ‘from St Paul’s cathedral to Millbank, or possibly from Hyde Park Corner to Waterloo Station’ (Sheail, 1991, p 196), provided the backbone of the UK’s electricity generating capacity. Now only two remain in service – West Burton and Ratcliffe-on-Soar, expected to decommission at the end of March 2023 and September 2024 respectively, while Drax may survive powered by biofuels. This imminent deadline catalysed the Science Museum’s formulation of a collecting project intended to include new acquisitions for the permanent collection that would represent Britain’s declining coal-fired generating capacity and the nuclear, gas and renewable plant replacing it.

Cottam power station

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221811/013Against this background, the Museum received a fortuitous approach from the team at Cottam power station in February 2019, outlining the forthcoming closure deadline and expressing a wish to see something of the site preserved in the long term. Contact was quickly established and an initial site visit was made within a month. This early visit is important in the collecting process, to establish personal contacts, find out what expectations and timescales are, to scope potential acquisitions and discuss what form the process might take.

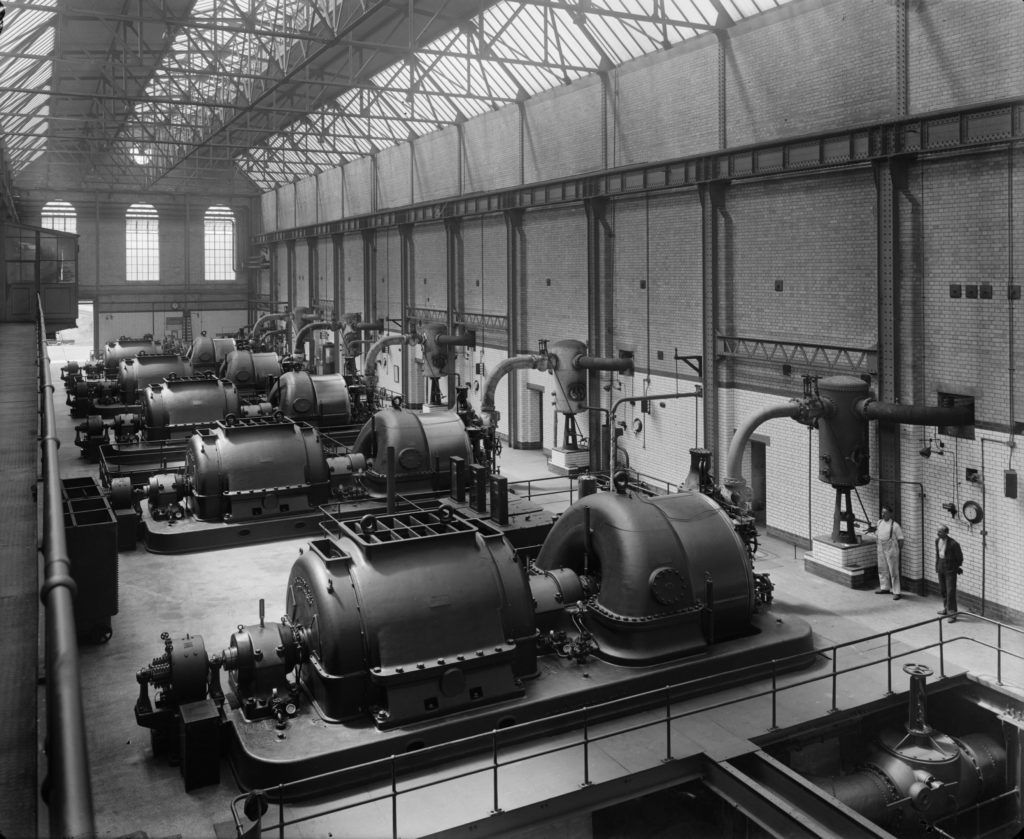

At this early stage potential acquisitions ranged from a complete low-pressure turbine rotor weighing 25 tonnes through to one of the bikes used by staff to get around the site. An image of the former gives a sense of the scale of engineering involved on the site (Figure 12); the latter illustrates the personal stories which can be conveyed with objects in the museum context.[14]

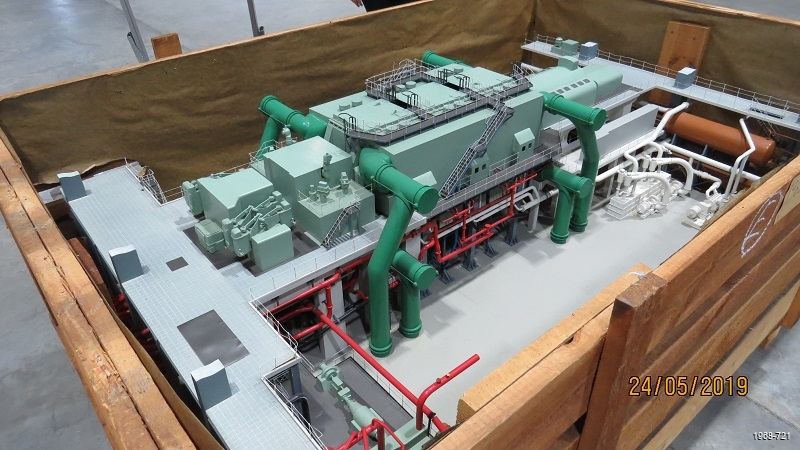

An early review of related collections highlighted that the Science Museum had in 1968 already acquired a complete architect’s model of one of the 500MW generating units from Cottam (Figure 13).[15] The presence of this item points to a contingency often used by (science) museums to represent large scale projects: acquiring a model as a proxy for the real thing (see de Chadarevian and Hopwood, 2004; and Morris, 2013). It also reinforced the position that an acquisition from Cottam would be desirable, embodying a long-term relationship with the site.

Development of the acquisition project thereafter followed two parallel strands, comprising the Museum’s internal process, and discussion on the scope of the acquisition with Cottam. Both were closely interlinked.

Given the resource demands of large acquisitions, a robust case must be made to win internal support to proceed. Elements of this case are logistical, including negotiation over the likely storage space required and establishment of a valuation.[16] Other elements are intellectual, involving a careful statement of the historical significance of the material in question. Both elements are balanced by the curator making the case to best persuade colleagues that the acquisition should proceed. With this particular case study that balancing took the form of a decision to seek permission to acquire something big from the outset, rather than smaller items or models:[17] the decision was taken, and approval given, to acquire the complete control desk from the No.3 generating unit at Cottam (Figure 14).[18] This was felt to be sufficiently impressive to convey the scale of the overall enterprise, while its modular construction met the Museum’s requirements for ease of handling and storage.

The control desk is in many ways a microcosm of the wider Cottam site. It is a masterpiece of technical design, automation and ergonomics. It allowed a single operator to control a machine of enormous dimensions (Figure 15) and Herculean capabilities; integral mills ground 4,500 tonnes of coal daily to the consistency of face powder and used it to raise steam to 2,300lb/square inch pressure and 1,051 degrees Fahrenheit temperature, producing a power output equivalent to a little under one-third that of the entire UK economy in 1870 (Kanefsky, 1979, p 373).

To start up and synchronise this capability to the National Grid involved some 900 actions over a period of approximately one hour – way more than the operator could humanly undertake, so a ‘Sequence Control’ system broke the process into ‘40 independent logical sequences’, each initiated by the operator but otherwise carried out automatically (Central Electricity Generating Board, 1971, p 549). How the operator oversaw all this was carefully designed; everything from lighting to instrument layouts was ergonomically modelled, mocked-up and tested to maximise comfort and efficiency (Central Electricity Generating Board, 1971, p 564).

The decision to acquire the control desk was underpinned by close liaison with Cottam’s engineering team. An initial appreciation suggested that only the central control unit might be acquired. However, discussion highlighted the integrated nature not just of the central desk but of the surrounding instrumentation panels, alarm fascias and even the lighting above. All had to be considered as a carefully designed ensemble. Following the decision to acquire the complete control desk, a specification for the dismantling and packaging of the desk was shared, based on one previously developed for a similar acquisition from the nuclear site at Dounreay. Detailed CAD drawings were prepared by the team at Cottam, who also helped carefully label everything, both to assist future reassembly and to dissuade anyone from quietly removing anything as a memento. All instrumentation was carefully removed and packed separately, and the entire desk was dismantled into its component parts and placed inside three 20-foot ISO storage containers for onward transmission to the Museum’s National Collections Centre[19] for storage.

As the physical acquisition had to reflect the desk’s integrated design, so it was important to take an integrated approach to the acquisition overall: the control desk itself was supported by a range of oral history interviews recorded with members of staff from Cottam, photography of them, the desk, and its context within the site, and the subsequent acquisition of the complete site photography collection detailing its construction and initial operation.[20] Additionally, a wider literature review added detail and interest to the acquisition file for future reference, including copies of the full historic building report for Cottam written by Ric Tyler, and even the superb, richly illustrated commemorative book produced by the Cottam staff themselves, which provides valuable human context to the site’s operation over 51 years.[21]

Reflections from a curator’s perspective

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221811/014Acquisition of an object as large as (or even larger than) the control desk is challenging. Two themes have recurred in the second part of this paper: logistical planning, and explanation to stakeholders of an object’s significance. Both interweave through the work of a curator in any such complex acquisition, and two final points can be made.

For all its scale and seeming permanence, the opportunity to acquire such large objects is often surprisingly ephemeral, even fleeting. It will rarely come while an item is in revenue-earning service, and once that is finished items will be rapidly decommissioned and disposed of. As part of the wider historic environment community this places an onus on curatorial teams to be proactive, make connections, and identify sites and specific objects which they wish to acquire, and communicate with all relevant stakeholders well in advance of any looming decommissioning deadlines.

Moreover, as objects in a museum collection rarely speak for themselves, so the project scope must ensure that the voices associated with the object are also captured and preserved. To do so is congruent with the recent historiography of technology, placing emphasis not just on invention or innovation but on the users of technology. It is a great paradox of our modern power-intensive economy that we are so reliant on power in everything we do, yet often so unaware of how it is generated. One of the lasting legacies of stations like Cottam was that, day or night, there were always guaranteed to be unit operators across the UK sitting at their control desks, quietly watching the dials and ensuring the capacity was available, stable and reliable, when the call came. Their stories are those which may well connect most closely with the Museum’s visitors.

Conclusion

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221811/015As highlighted at the beginning of this article, at the closure of many recent industrial enterprises historical knowledge can quickly, at best, become spread between institutions, with most of its larger material culture represented by its buildings and plant being demolished and scrapped. Private archives may face an uncertain future and the intangible memories of working practices and culture are dispersed with the breakup of the workforce. In the future this issue of distributed collections may become less concerning if through a mechanism such as the Congruence Engine disparate databases may be seamlessly searched. The inclusion of archaeological sources may also make these more widely accessible to other disciplines who have traditionally rarely used evidence from studies of the material world.

The Congruence Engine is demonstrating how, by combining data from diverse collections, more engaging narratives of people, places and objects may be constructed and unexpected connections explored. These initial results argue for closer future collaboration between heritage institutions and other communities to ensure that a more collective approach is taken by responses in the sector to obsolescent industries, plant and technologies. Will the Congruence Engine form a method of addressing the dis-congruence of knowledge that occurs when an industry or technology becomes redundant? Will the greater awareness of resources beyond usual professional spheres of interest and interaction influence how the heritage sector responds to closures of contemporary industries? Perhaps in the future curatorial practice across the historic environment, museums and archive sectors will ensure that data and objects related to obsolescent industries are collected in such a manner as to make a Congruence Engine obsolete.