Contexts for photography collections at the National Media Museum

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/170710

Introduction

A museum decides to transfer its collections to another museum. After assessing its financial situation, reviewing its priorities and strategic aims, its opportunities and contexts, the museum makes the difficult decision to enter into negotiations with another, better-resourced institution in order to safeguard the collections in the public interest. Both museums agree to collaborate closely, and enable the former custodians to use the collection when appropriate in their exhibitions and displays.

The museum in question was Brooklyn Museum and Art Gallery, which in 2007 transferred their sizable costume collections to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[1] Accumulated over a number of years, the collections were considered to be important, but the Museum, which cares for over 1.5 million works of art across all disciplines, increasingly felt that it was not possible to sustain the levels of investment in collections care and curatorial resources that such a significant collection required. After a review of different potential destinations Brooklyn decided to work with the Met, whose costume institute has a staff of over twenty specialists and where the collection would complement their own holdings of costume, creating the ‘largest and most encyclopaedic costume collections in the world’.[2]

The focus of this paper is another transfer of museum collections in similar circumstances – the 2016 transfer of the Royal Photographic Society (RPS) collection from the National Media Museum[3] (NMeM) in Bradford to the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in London. This collection of over 250,000 images, pieces of equipment, books and papers, contains work by many celebrated photographic artists including Alfred Stieglitz, Edward Steichen, George Davidson and Alvin Langdon Coburn. The decision by the National Media Museum, and its parent body the Science Museum Group was announced in early February 2016 and, unlike at the Brooklyn Museum, the NMeM decision resulted in considerable public comment, campaigns by local politicians and a petition opposing the transfer that was signed by over 25,000 people.[4]

This essay is not an explanation of this decision, which has been made in repeated public statements by the Museum, most notably a blog posting by Director Jo Quinton-Tulloch[5] and an article in the Guardian by Science Museum Group Chairman Dame Mary Archer[6], nor is it a narrative description of the decision-making process. Rather, I want to explore why the transfer became a controversy by exploring the arguments mobilised by critics of the transfer, on the need for a National Museum of Photography, on the divide between art and science in photography and on the inequalities between London and the north of England, to understand why certain narratives gained apparent resonance and why others – not least those related to professional decisions related to resources – were not effective. I also want to widen the debate by contextualising the transfer in a set of different narratives: museum debates around disposal and sustainable collecting; the effect of changes to museum funding in the UK since 2010; the long history of the collections that form the National Media Museum; and the local situation of the museum within the city of Bradford.

I ought to acknowledge that I am far from a disinterested party to the events described. As Head of Collections and Exhibitions at the Museum since 2013 I was one of the Senior Managers who was party to the decision to transfer as well as other related decisions that are set out by Jo Quinton-Tulloch in her editorial for this volume of the Science Museum Group Journal. Throughout 2016 I spoke at conferences[7] specifically on this issue, as well as engaging in discussions with many people inside and outside the museum and photography sectors. While by no means impartial, I hope that, writing a year after the decision was made public, I am able to reflect honestly and objectively on the events and that these insights may be a constructive contribution to our understanding of museums, collections, and their public role.

The arguments mobilised against the transfer

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/170710/001Reflecting on the events of 2016, it seems to me that in our public statement about the transfer the Museum wandered, perhaps naively, across a series of powerful crosscutting narratives that made the rationale offered difficult to understand or accept. These can be summarised as follows: the idea of a ‘national museum of photography’; the art/science problematic; and the London versus the North dynamic. On each of these points our attempts to offer explanations that complicated or challenged the dominant narrative were unsuccessful in public forums, even if in private at least some of our critics could be persuaded to respect our decision. This is in large part because these powerful narratives operated as shortcuts to longer and larger political debates about inequalities and resources. At the same time, as I will demonstrate in the second section, these narratives while operating as apparently ‘common sense’ also have the effect of occluding and reinforcing other, equally problematic, power dynamics.

Criticism of the Museum emanated from a range of different sources over the course of 2016, and I have drawn from a number of these including an open letter signed by 88 former members of staff and high-profile photographers published in the Observer newspaper on 6 March and an interview given by former Museum Director Colin Ford on the BBC Radio 4 programme Front Row on 10 March. Other comments have been drawn from newspaper articles, blog posts, social media posts and comments beneath the line on official statements made by the Museum in February and March.

Narrative 1: ‘the end of the National Museum of Photography’

There was a powerfully made argument that the transfer of the RPS collection represented the end of the comprehensive ‘National Museum of Photography’. Speaking on the BBC Radio 4 programme Front Row Colin Ford, the founding Director of the Museum, said:

It seems to me that every nation should have a national museum of photography, it’s such an important medium, and one of the press releases that first came out with this story said that there will be no national museum of photography – which is appalling.[8]

Eamon McCabe, photographer and formerly picture editor at the Guardian recounted the circumstances that led the Museum to change its name in 2006:

I wrote to tell the new director what I thought of the change. “Don’t worry,” he replied. “We’ll have a chair in photography.” “A chair!” I said. “We used to have a whole museum.”

Commenters beneath Jo Quinton-Tulloch’s blog post of 4 February explicitly called for a national museum of photography:

We should be reinstating the National Museum of Photography in Bradford – with a photography specialist heading it up.[9]

Indeed, the idea that the National Media Museum was the National Museum of Photography was actively promoted by the Museum up to 2016, with reference on the website to ‘The National Photography Collection’, and its 2010 Collecting Policy Statement claimed that:

these collections reflect [the Museum’s] remit as the primary National resource in its subject areas.[10]

The idea that we were the ‘National Museum of Photography’ was a fiction – marketing language to assert the collection’s significance, not to be taken literally. Many other nationally designated archives and museums in the UK hold highly significant photography collections: Tate, the National Portrait Gallery, the National Maritime Museum, the National Archives, the British Library, National Museums Northern Ireland, National Museums Wales, National Museums Scotland and, of course, the V&A, all have significant collections of photography, and many more non-national museums also have important holdings. As I had taken it to be incontrovertible fact that we have in this country a distributed national collection of photography, it seemed to me that the desire to create a ‘National Museum of Photography’ was less about the needs of preserving photographic heritage, and more about making a claim for the status of photography as a distinct form of cultural production – ‘the ultimate democratic medium, the most popular art form’.[11] Odd how we never hear the same about textiles or costume, odd how we never hear the same about sculpture or watercolour painting. If we think about the benefits of a distributed national collection in terms other than status then we can see that the great benefit of a distributed anything is its resilience, its flexibility, its ability to adapt, change, reinvent itself. To take this incredibly rich heritage, to attempt to institutionalise into a ‘National Museum of…’ seems to be very much a nineteenth century solution for a medium that is profoundly part of our twenty-first century lives.

Yet, looking back, I had not fully appreciated before 2016 the work that this idea was doing, or how important it was to so many people. Photographers who looked to the idea of the Museum as a validation of their status and work were upset that we were apparently downgrading its importance and, by implication, theirs. People in Bradford who saw the Museum as a validation of the city’s cultural prestige were equally upset that it marked an apparent downgrading of its status, and therefore of the city itself. This traditional conception of the museum as an institution of treasures and experts has great public resonance. And yet this idea of museums is a fiction and a dangerous one: all collections are partial and imperfect; all knowledge and expertise is subjective and limited. Museums attract great public affection, but I wonder whether that is based on a misperception of museums not matched by the operational realities and one that cannot usefully persist into the twenty-first century.

Narrative 2: Reinforcing a divide between art and science

The other major claim was that in transferring the RPS Collection the Museum was establishing a divide between ‘art’ and ‘science’ in photography. The Museum has consistently claimed that the RPS collection ‘…can be broadly defined as “art photography”’ and that its transfer allows the Museum to focus on its core purpose as an institution of science and technology.[12] The Observer letter of 6 March clearly asserts that:

the present move to separate the interdependent aspects of the art and science of photography reverses prevailing worldwide practice, and takes the study of photo history in Britain back several decades.

On Front Row, Colin Ford elaborated on this by claiming that the Museum had been established to avoid this distinction:

In my day, and for some years after I left, on the front door of the Museum it said this is a museum about the art and science of photography. And our aim, it didn’t always work, but our aim was you never showed a photograph without showing the sort of technology that produced it; you didn’t show a camera if you didn’t show the sort of pictures that it took – because they’re inextricably entwined.

Some took a slightly different approach, asserting the importance of arts over science and technology:

It’s not scientists that produce the next blockbuster or multi million pound game. It’s people with an aesthetic. That’s what film, photography and digital imagery is all about. The technology is just a tool, its [sic] story telling aesthetics, meaning and emotion that takes that to global success. That’s art by any other name, or at least craft which is what photographers generally describe their activities as. Not Science.[13]

Others were more direct:

Can we talk about how fucking AWFUL it is that the National Media Museum is being turned into a science museum???[14]

And

#nationalmediamuseum should be about much more than ScienceTechnologyEngineeringMedicine. What about people,stories,imagination? [sic][15]

On reflection, we ought to have been more careful in our approach to these ideas, given the institutional and cultural histories, not to say the deeply held convictions of those committed to art and to science that they are each under-resourced and under-appreciated compared with the other.[16] As I will explore later in this paper, a distinction between photography made by artists, and photography in other contexts, is one that exists in the institutional divides between the Science Museum, the V&A, Tate, and any number of other museums that hold photography. It is the National Media Museum’s original sin that when we opened as the NMFPT in 1983 that we had failed to adequately resolve the distinction between collecting areas with the V&A. In the years that followed its opening the Museum did set out to acquire a collection of historic photographs, in direct competition with the V&A. We do have copies of, for example, the same images by Julia Margaret Cameron that are also held in not only the V&A but also the National Portrait Gallery. Furthermore, as I will explore further below, the Museum deliberately excluded scientific photography, and commercial Bradford photography from its ‘national photography collection’, undermining its claim to be a comprehensive collection of all aspects of photographic culture.

However, it is clear that in 2016 we failed to adequately give form to the alternative approach that we were advocating – we were clear about what we were against (art photography), but we were vague about what we were for. In this new direction for our photographic collections we plan to integrate all the many and various categories, meanings and statuses of photographs, and the lens of science and photography is central to this. Critically, this approach will focus on non-canonical photographs and photographers; photography that operates in spaces that have been neglected by the processes of institutionalising and mainstreaming photographic histories exemplified by the RPS collection.

Narrative 3: The North-South Divide

And finally, the most powerful of all narratives, the inequities of London compared with the regions, and specifically with the north of England. As Brighton-based art-historian Francis Hodgson put it:

The outrage has centred on the impoverishment of Bradford and the North of England in favour of a metropolitan cultural holding already rich in photography.[17]

The open letter in the Observer of 6 March indicated that the move was an apparent contradiction of the then government’s publicly stated ‘Northern Powerhouse’ policy:

Moving most of the museum’s photography collection away from Yorkshire goes against government policy when the museum was opened – to put such facilities outside London – and against the present government’s claimed ‘northern powerhouse’ strategy.[18]

Although for Colin Ford himself, the location of the Museum was actually of little importance compared with the need for a single comprehensive National Museum of Photography:

I’m actually much more passionate about the fact that there should be a national museum of photography wherever…[19]

Interestingly two of these three narratives came together in a strong thread of comment on social media that claimed the move was motivated by a ‘patronising’ connecting of the associations of the North of England with industrial heritage and the Museum’s new focus on science and technology:

And as others have noted, the basic assumption of those in London…is that the north can be allowed a National Museum of Pistons or some other nod to the industrial past, but that’s yer lot. Sheer cultural Gradgrindery.[20]

And

It’s nice to see that SMG believes that once you get north of Liverpool that museums dedicated to science, trains, science and trains respectively helps the whole country’s access to the arts. I thought that we’d got past that ‘up there for the industrialists, down here for the aesthetes’ attitude about 200 years ago but apparently not.[21]

I would not dispute that there are inequalities on a number of different economic and social measures between London and the South East and the North of England, and specific differences in funding for cultural institutions. The 2013 report Rebalancing Cultural Capital rightly identified that not only does London take the lion’s share of cultural spending in the UK, but that cultural spending decisions are also centralised in a way that is not the case in other comparator countries.[22] The NMeM Advisory Board and Board of Trustees were very conscious that they were making a decision that could be characterised as further evidence of this inequity. However, the public discussion last year tended to ignore or gloss over two significant aspects of the problem. Firstly, there was little discussion of the fact that the removal of direct subsidy from central government had reinforced this trend, as it’s easier to raise money from non-public sources at the heart of the international art market and the engine room of economic growth. Like the failure to mobilise an anti-austerity argument, critics of the transfer decision seemed to be in denial about the economic facts, addressing themselves to a symptom but ignoring the systemic economic causes. Secondly, while it was often asserted that the collection ought to be located in the north, in fact under the NMeM’s care the RPS collection was actually held in three separate locations: at the Museum in Bradford; at the Science Museum’s storage facility at Wroughton in Wiltshire; and at the BFI’s storage facility at Gaydon in Warwickshire, where there are specialist facilities for storing nitrate film. Furthermore, the physical location of a collection is a zero-sum game – for it to be somewhere, it must necessarily not be everywhere else. I would argue that it’s less important where collections are held than they are invested in, made available, catalogued and digitised – activities that the V&A can do in London partly because they are able to draw on private funding available from being in the cultural capital of the UK.

Disposal and transfer of collections in contemporary museum practice

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/170710/002The public perception of museums is that of stable, enduring institutions with collections that, once accepted, are to be maintained in that place forever. Yet, in reality, objects and collections have always circulated between collectors, institutions and the world at large. Such processes are accepted curatorial practice. As well as the example of Brooklyn Museum’s costume collection given at the start of this paper one might also cite the medical collections at the Science Museum that are on loan from the Wellcome Trust, the transfer of navigational instruments from the National Maritime Museum to the Science Museum in the 1990s, 500 objects from the Americas, Africa and Asia that were transferred from National Museums Wales to the Horniman Museum in 1980, and the transfer of early twentieth-century sculpture from the V&A to Tate in the early 1980s.[23] Indeed, a major part of the National Media Museum collection, the Daily Herald Archive, was itself transferred to the Museum from the National Portrait Gallery in 1983. And where collections are disposed of by museums, two thirds of them find their way into other museums’ collections (Merriman, 2008). It is rare that museum objects that are in good condition are removed from the ecology of accredited institutions.

While accepted professional practice, disposal from museums is controversial, perhaps precisely because it seems to contradict the function of the institution as a place where collections are maintained in the public interest. In 2003 the National Museum Directors Council (NMDC[24]), published a report, bluntly titled Too Much Stuff?. Intended as a contribution to the then current discussions on the disposal of museum collections, it set out a bold statement that museums should:

be willing to dispose of objects when this will better ensure their preservation, ensure that they are more widely used and enjoyed, or place them in a context where they are more valued and better understood. Disposal should be regarded as a proper part of collection management.[25]

And went on to remind readers that:

Collections are held not for the benefit of individual institutions, but for the public as a whole.

However, despite this categorical endorsement of disposal as a valid and important part of good collections management, it remains one that is still only rarely used by museums. Writing in 2008 in the journal Cultural Trends, Nick Merriman was disappointed that museums were failing to use disposal adequately as a way of dealing with what he saw as a looming sustainability crisis. Merriman noted that while the ethics of disposal had been largely settled by successive updates to the Museum Associations Code of Ethics[26], museums were simply not using it. At the same time public collections continued to grow rapidly, with acquisitions outstripping disposals at a rate of between seven hundred and fifty and one thousand to one.[27] As stored collections are not resource-neutral but require continued investment in collections care, documentation, digitisation and the facilitation of public access, the exponential growth of museum collections poses a very serious challenge to the financial and environmental sustainability of museums. But pragmatic, managerial motivations for disposal are not, in themselves, effective. Merriman sought to provide a further rational, ascribing the ‘taboo’ and ‘presumption against disposal’ as stemming from nineteenth-century conceptions of museums as ‘an objective record of collective memories’.[28] He argues that we should instead accept the implications of post-modern approaches to knowledge:

If we begin to see museum collections as historically contingent and partial, and we accept the implications of academic discourse on forgetting, then this frees us up to take our own responsibility for active stewardship of collections rather than feeling that the role of the curator is simply to accept their predecessors’ decisions which have to be preserved intact for an indefinable posterity.

This is a powerful argument for museums and for curators to actively shape their collections in line with their current needs, rather than passively maintaining them for their own sake. However, as we will discuss later, this view of museums is not one that is well understood outside the profession and, in fact, runs counter to prevailing public sentiment.

The effects of austerity on museums

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/170710/003Merriman was writing before the change of UK government in 2010 that heralded significant reductions in public funding for museums which have made the issue of the financial sustainability of collecting institutions even more pressing. The Science Museum Group has estimated the cumulative impact of successive statements by Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne between 2010 and 2015 equated to a third of the museums’ revenue budget. While those other museums funded directly by national government though the Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) were equally affected, even more severe cuts have affected local authority-funded museums. And while in the 2015 Autumn Statement Osborne indicated a change of tack by recognising the value of investing in the broader cultural sector[29], the situation for these local authority museums remains desperate. In many cases, local authorities have closed or mothballed museums pending potential re-opening by groups of volunteers. In Lancashire, the County Council closed all of its five museums as it attempted to save £262m over five years from 2016.[30] In Ilkley, the Manor House Museum, run by Bradford Council, has been closed while agreement is reached with a friends group to operate the house.[31] Other museums have been responded by cutting opening hours[32], while some have introduced admission charges.[33]

Significant reductions in funding have the effect of forcing governing bodies to prioritise activities that are central to their purpose. As Paul Womble puts it in the British Journal of Photography, ‘cuts make you focus on your perceived core values and aims’.[34] For the National Media Museum the strategy has been to redefine the core purpose of the Museum as being more closely aligned with the other museums in the Science Museum Group, of which it is a part. While it could be argued that this change in strategic direction was necessary for a museum that was widely seen to have lost its focus, it would be hard to see the subsequent events happening in the same way without the financial driver of making savings. Rather than go down the route of retrenchment, closure and reductions, the National Media Museum shifted its core values and aims to a position from which it was better placed to not only withstand short-term financial challenges, but also build on its strengths and make a real contribution to its communities. One of the implications of this strategic shift, however, was that the maintenance of some assets and some activities, and the allocation of scarce financial resources to do so, was no longer defensible.

To return to the public debate in 2016, the funding context is certainly present in the public discussion in March and April 2016, although it is notably not central to the debate. The Observer letter on 6 March makes no mention of the funding situation at all, but refers obliquely to curatorial redundancies.[35] In a discussion on Radio 4’s Front Row on 30 March the issue was glossed over by Colin Ford as a segue into a different argument about the decline in visitor numbers.[36] Even campaigns by local Labour MPs did not address funding in relation to the transfer[37] – surprisingly, given the wider political context of a Liberal Democrat/Conservative coalition government’s funding decisions. It was left to the Museum itself to make the direct connection in a blog post written by Director Jo Quinton-Tulloch on 6 February.[38]

The NMeM: three key contexts for the transfer design and our future direction

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/170710/004Museums are institutions that continuously exist in different temporal states. Every day we welcome visitors, run events and learning programmes for schools and families, and show films. Every year we show a programme of temporary exhibitions and deliver a series of film festivals. Every 5–10 years we open new ‘permanent galleries’, themselves designed for a lifespan of 10–20 years, and refurbish our public spaces, shop, café, cinemas. But, at the same time, we also maintain collections, many of them hundreds of years old that have extensive pre-museum biographies. It’s not coincidental that museum departments and activities tend to be aligned with these different time-spaces – learning and operational teams with the day-to-day, exhibitions departments with the 2–5 year programme, curators with the long-term collections management and gallery planning. Over time, and in stable disciplinary and institutional circumstances museums establish a rhythm to the activities and they get knitted together in an institutional culture where ideas flow between people and departments.

The National Media Museum is, however, not this museum. A relatively young institution[39], it is part of a larger group of museums with whom it is formally a single legal entity[40] and from where it drew its founding collections. While some of its functions are managed locally, others are administered centrally. Its collections, formally, are a single collection, albeit one distributed between seven[41] different geographical locations. Rather than thinking of the National Media Museum, or the wider Science Museum Group, as a single institution, it is more accurate to think of it as part of a network of different people, departments, locations, collections and activities.

Context 1: a longer history of collecting

The roots of the National Media Museum are in the Great Exhibition of 1851 which led to the establishment of the South Kensington Museum and, in 1909, the Science Museum. In this time the foundations of the collections that became part of the core of the National Media Museum were laid down: with the development of the photographic collections from 1882[42]; the cinematography collection from 1913[43]; and the television collection from the donation by John Logie Baird of his experimental apparatus to the Science Museum in 1926. These collections developed over time, and in 1983 some of them were sent to Bradford to form the basis of the new museum. Legally, the collection was not split; the collections remained as a single entity.[44]

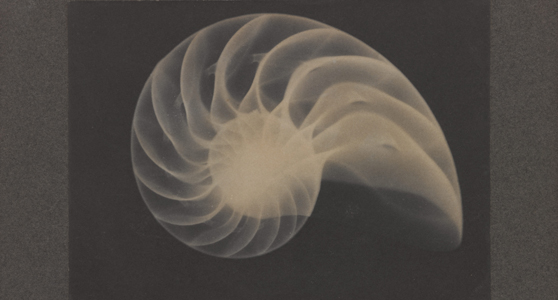

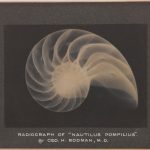

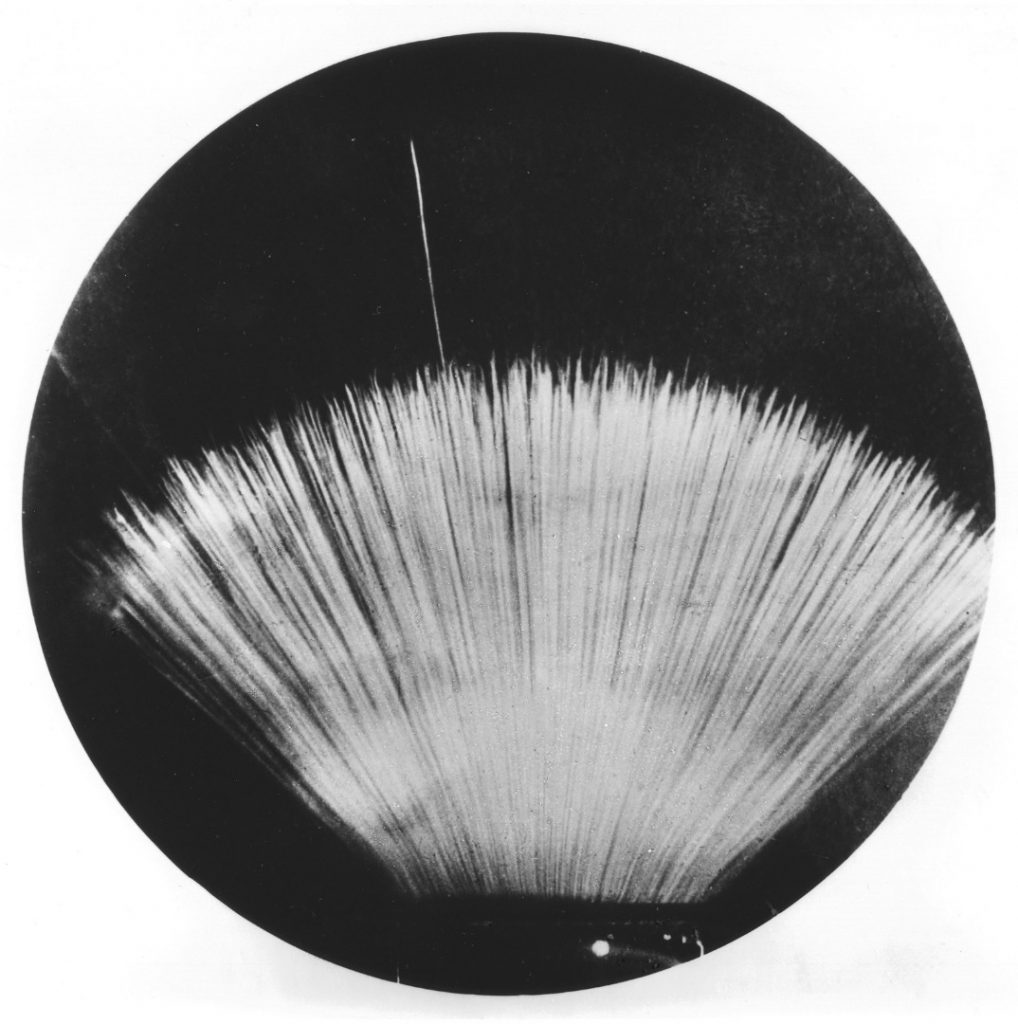

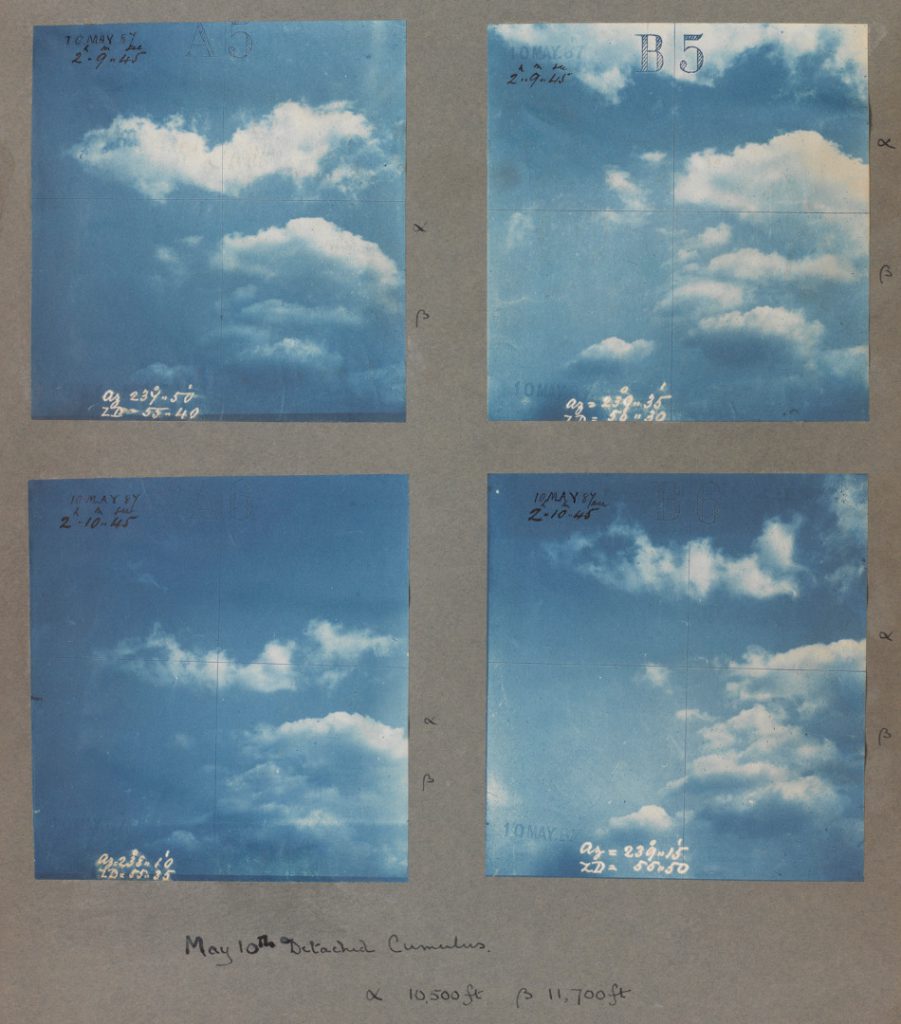

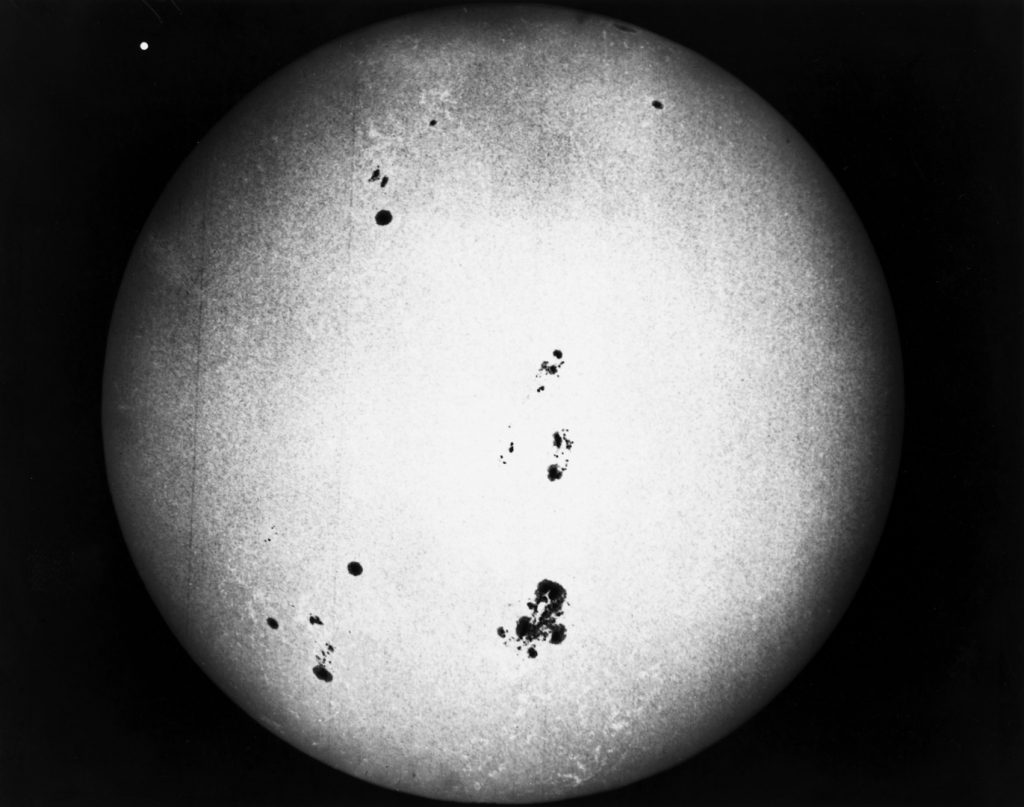

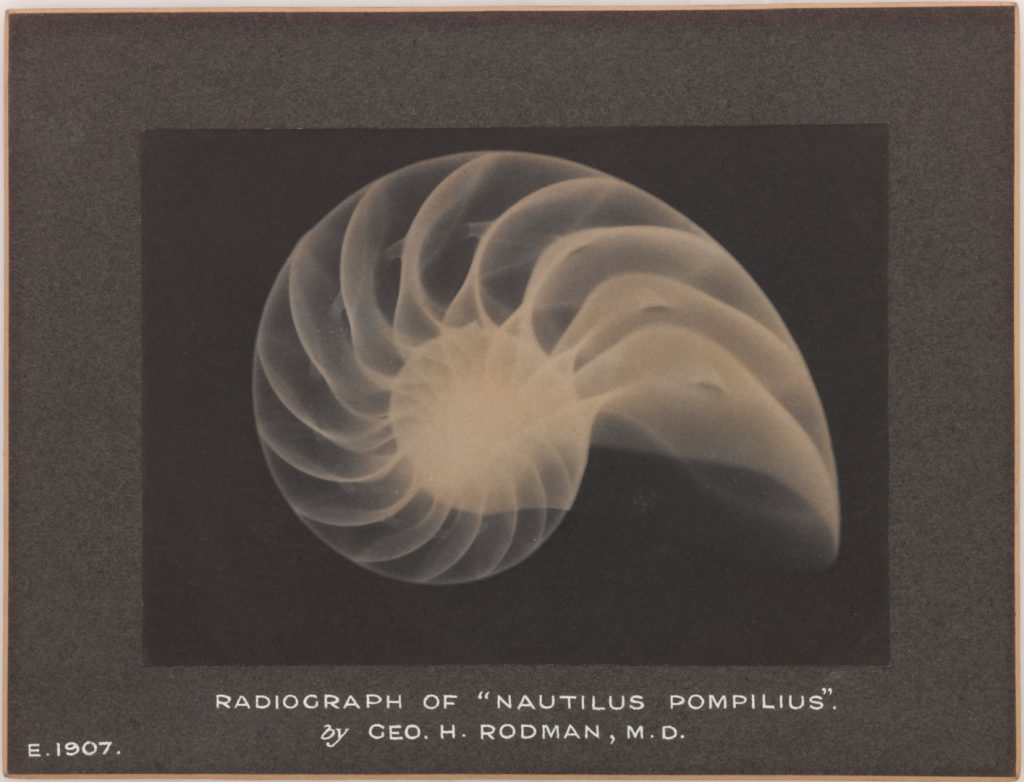

It’s not, however, as simple as saying that all photography, cinematography and television collections were allocated and delivered to the new museum. It is clear from the catalogue records and the locations of the collections today that choices were made. Radio broadcast (in spite of the direct links to the development of television) and sound recording and reproduction technologies (in spite of its close relationship to cinema technologies) remained at the Science Museum. The new museum was focused on images, even where these images were experienced with audio accompaniment and even where the technological histories were closely interlinked, the image was the focus and the sound deemed entirely extraneous at the new museum. More curiously, within photography a process of disentangling different categories of photography took place. Scientific photography and imaging processes remained at the Science Museum. Medical imaging and photography, including X-rays, also remained at the Science Museum. It seems that far from creating a museum that covered the ‘art and science’[45] of photography, conscious decisions were taken to exclude scientific photography and scientific practitioners of photography from the new collections, and hence from the intellectual realm of the National Media Museum.[46] The National Museum of Photography was being established and science was not part of its thinking.

But what was it thinking? A comment piece published in the British Journal of Photography at the time expressed serious concerns that there was not enough distinction between the collecting approaches of the new museum and that of the V&A: ‘if…Bradford is going to set out to acquire a permanent collection of historic photography as an end in itself, triplicating the V&A and RPS collections, then taxpayers will have every right to object’.[47] Furthermore, in the concluding paragraph, the writer calls for ‘clarity’ of collecting focus for each museum, ‘no one is going to deny Bradford must house or negotiate to have access to a wide range of photographic and film images but it is pointless for it to compete in the over-priced art market’. More strikingly, he goes on the finish with a call for the Museum to confidently show replicas of original photographs rather than wrangling for historic collections: ‘Why make an elitist gambit from a process invented to provide unlimited copies for all to enjoy? All concerned should keep their eye on the ball – serving the public – not on building personal empires.’

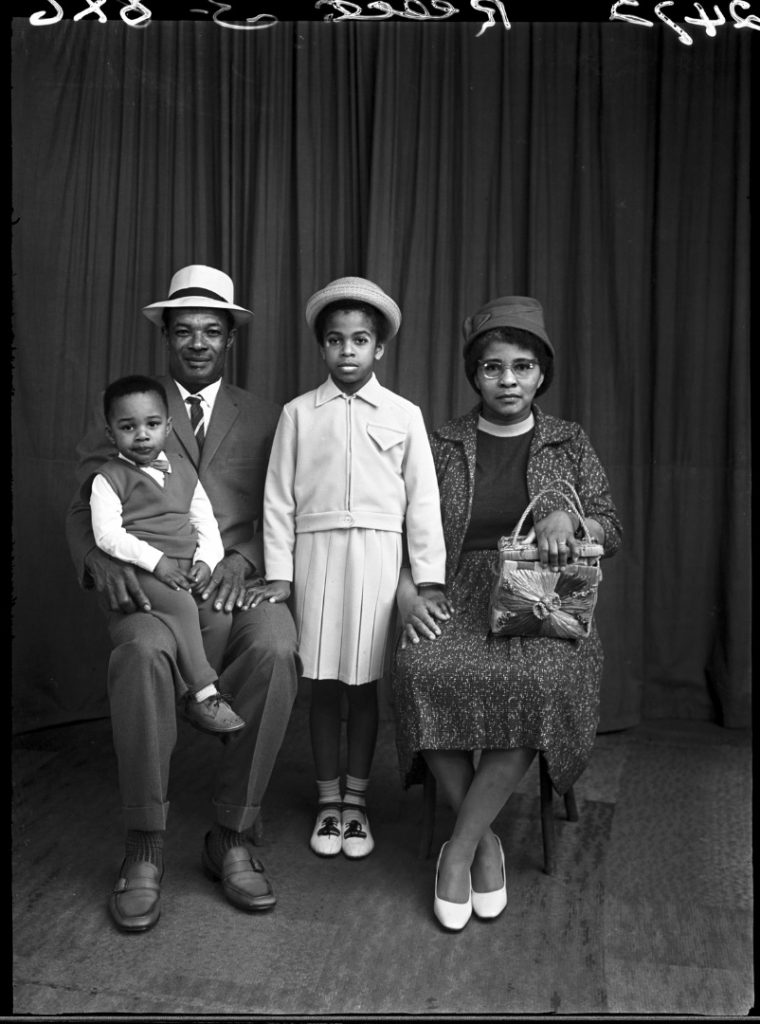

The problem with claiming to be the definitive national museum of something as diverse and complex as photography is that there are simply so many photographs, so many cameras, so many associated technologies of reproduction and dissemination, so many different applications of those technologies. In an effort to assert itself, the Museum collected, in my view, without discrimination in the early years. It acquired the Kodak Museum collection, the Ricketts collection, the Focal Press collection, the Daily Herald picture library (of over three million prints), and archives of work by Arthur Nurnberg, Zoltan Glass, Tony Ray-Jones and Lewis Morley. Proactive, thoughtful collecting is part of a healthy museum practice; this was not thoughtful, considered collecting. An internal document from 2013 exemplifies the expansive nature of the collecting ethos, referring to ‘…a comprehensive collection of the medium’s various cultural histories’.[48] Except, again, some cultural histories were being excluded. In 1985 photography Tony Walker, proprietor of the commercial Belle Vue Studio on Manningham Lane in Bradford, that had been one of the city’s main photographic studios between 1926 and 1975, offered the material from the studio to the National Media Museum. This archive of thousands of glass negatives showed the work of a typical commercial photography studio throughout the twentieth century, and charted the changes in Bradford’s population as it accommodated migrants from many parts of the world, including significant numbers of people from Pakistan and the Caribbean. This archive was, however, rejected on the remarkable grounds that it was of local, and not national importance, even though other Yorkshire photographs were acquired (including a long-running series of commissions in the city – the Bradford Fellowship series), as well as other commercial and studio photography. Fortunately the archive found its way to Bradford Museums and Galleries where it has become one of their most celebrated photographic collections.[49] Clearly, subjective curatorial decisions were at play here, shaping what was deemed suitable for the national collection, and categorising other material as inconsistent with the authorised version of photographic history.

Context 2: A responsible approach to collecting

The acquisition of the RPS collection in 2002 is a key moment in the Museum’s story. In the much-quoted words of Michael G Wilson[50] it was the moment at which the Museum collections became ‘world class’.[51] This collection of over 250,000 photographic images, items of equipment, books and archival materials was bought by NMeM after the RPS board had come to the conclusion that it could no longer afford to maintain it properly alongside the other activities of the Society.[52] As well as funding for the purchase itself, the Museum received further funding for cataloguing and storage facilities in the Museum. The Museum began exhibiting the collection in its temporary exhibition programme immediately, with the 2003 exhibition Unknown Pleasures: Unwrapping the RPS Collection.

A change in Museum leadership in 2005, and the renaming in 2006, began a new phase for the Museum’s collections. From a defined collecting remit focused on photography, film and television, the Museum signalled the intention to begin a radical new expansionist phase ‘colonising new media territories’, to quote one internal document from the time. Comprehensive lists of topics and areas were drawn up[53], and in 2010 the Museum’s collecting policy statement declared that ‘…the NMeM’s potential to attract scholars, donors, vendors or patrons must suggest that their status is that of the primary national Collection of each of the media it represents’ (my italics). Generously, it also stated that ‘…other institutions may have exemplary holdings in more focused aspects of the museums…’[54] but that the primary national collection was that of NMeM. This attitude to other collecting institutions included the other museums in the Science Museum Group, with NMeM effectively acting as a silo and actively planning to duplicate collections: a section of the 2010 policy details the intention to collect Radio Broadcast equipment and technology, even though this area was already very well covered by the communications collections held at the Science Museum.

A further change in leadership in 2012 began a process of moving away from this expansionist position. A restructuring of the curatorial team that year led to a refocus on the three core areas of photography, film and television, which, even after six years of the aspiration to collect more widely had not led to the development of significant collections in any other areas. At the same time, the Science Museum group began a review of its storage facilities, partly to consolidate a number of stores in a single location to reduce costs, but also in anticipation that it would have to move out of the West London Blythe House stores. It was in this context of reduced funding, the need to create sustainable collections that supported the Museum’s strategy, that the RPS collection and others were identified as potentials for transfer to other institutions. Indeed, in 2015 the Museum transferred a collection of TV adverts to the BFI[55], and it is possible that the Museum may consider other transfers to appropriate institutions in due course.

As the 2016 debate played out in public, two aspects of this wider context of the collection were mobilised; the timeline and the supposed comprehensive nature of the collections. A selective timeline was deployed; reference the establishment of the Museum and reference to the name change in 2006[56] – because they are the touchstones for the photography community. Some made the point that the Museum had acquired the RPS collection in 2002.[57] The British Journal of Photography article by Paul Womble[58] charts the course in more detail. He writes that ‘it should be remembered that the Royal Photographic Society Collection has been on the road for some years’, and rightly traces the institutional formations back to the South Kensington Museum. But the idea that the collection was a perfect amalgam of art and science and every aspect of photography was mobilised time and again.[59]

To return to Merriman – collections are not perfectly formed things, but are the imperfect creation of generations of collectors, administrators and curators, partial, incomplete, highly subjective. It is right that we do not treat them as ‘treasures’ to be venerated, but as things to be used and actively shaped and managed. As circumstances change, as institutional formations evolve and develop, so must collections.

Context 3: Bradford

The final context that I want to explore is that of our city, Bradford. Since 1983 Bradford has not become, as the city planners had hoped at the time, a tourist destination. Indeed, the impacts of deindustrialisation, evident before 1983, have been compounded by other events that, cumulatively, have made the city, however unfair this characterisation is, a byword in media discourse and to some extent in the public’s imagination, for poverty, social and ethnic segregation and discord. Recent regeneration initiatives are changing this perception, but the city continues to face real challenges in education and economic development.

The Museum contributes in the order of £20m to the local economy each year, but the city is far more than the Museum. It is a large, complex city and wider metropolitan district, with its own challenges, histories and place in the national imagination. Since the Museum opened in Bradford in 1983, a decision[60] made more by luck and happenstance than cold, hard, strategic planning, it has suffered a series of events that have contributed to a general public image that is extremely (and not always fairly[61]) negative. The Bradford City football stadium fire in 1985; the Ray Honeyford affair[62]; the reporting of events relating to the publication of Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses[63]; civil disturbances in 2001; and the lengthy delay between demolition in 2004 and the start of construction in 2013 of the Broadway shopping centre that ‘left a hole in our city centre’[64]. The cumulative effect of these widely reported events have led to a situation where Bradford has become lazy journalistic shorthand for poverty, racial segregation, and fears of radicalisation.[65] Sean McLoughlin from Leeds University has written that Bradford has become a ‘bad news place’, associated with its well-established South Asian communities who are often framed as ‘problem’ and ‘suspect’ citizens due to their connections to people, places, faiths, cultures and histories elsewhere (McLoughlin, 2014a:21).

In all of the discussion around the ‘National’ questions of photographic and cultural heritage in relation to the RPS transfer, this local context has been reduced to a pair of simplistic rhetorical points: the contended hypocrisy of a government that was encouraging a ‘northern powerhouse’ at the same time as underfunding its cultural institutions; and the decline of Bradford, which plays freely with the idea of the city as a ‘bad news place’. In this version, Bradford is a place always at deficit: enhanced by the opportunity to host ‘national’ cultural assets and reduced by their removal. That which is valuable (funding, collections, cultural capital) is implicitly always from elsewhere, not from the city itself but bestowed on it by benevolent external actors. Interestingly, there were no appeals to retaining the RPS collection on the basis that some of the photographs were made in Yorkshire, or made by people from Yorkshire[66], because, perhaps, this would undermine the rhetorical usefulness of Bradford as a place of deficit and loss.

Often, when the Museum has been reported or commented on in the specialist press, there has been a tendency to conflate the Museum and the city. ‘Bradford’[67] comes to stand in for institution, locale and, in 2016, the decision to transfer. This may be shorthand, but its reveals that, for the writers, Bradford means the National Media Museum, and, to a certain extent and in the context in which these articles are published, the decision on the RPS collection. And, as noted above, the word itself has already come to stand in for a range of negative associations, so it is not necessary to make reference to the city’s diversity, or its poverty or its challenges around any number of public policy areas because that is already present in the word ‘Bradford’. At the same time it erases the city itself, a place of culture and creativity – and while we seek to play a crucial role in the city, the Museum and the RPS collection are far from being the only good things Bradford has going for it. This shorthand is only possible to make if it is a place to which you have never actually been or, if you have, only to visit the Museum.

Epilogue

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/170710/005Since the transfer of the costume collection to the MET, Brooklyn Museum has continued to transform itself into a ‘more populist and inclusive institution’.[68] Audiences are up, with more than 540,000 visitors in 2014 compared to a low point of fewer than 200,000 per year in the late 1990s. Having successfully reengaged with its locality, it now attracts a more diverse audience, forty per cent of whom come from non-white groups, and whose average age has come down from 58 in 1997 to 35 in around 2012.[69] As well as innovative new programmes, the Museum has won plaudits for its innovative approaches to digital engagement.[70]

In her blog post written at the start of the controversy in February 2016, Director Jo Quinton-Tulloch made a direct plea for people to ‘stick with us’. In March 2017 we opened a new interactive gallery, the result of a £1.8m investment by the Science Museum Group, and the foundation for schools and family visits to the Museum. In 2021 we will open a further series of collections-based galleries that will represent a further £5m investment in the building including improvements to visitor facilities and circulation. We have received funding from Google for an innovative science learning programme targeted at some of the most deprived areas of the city, and we are playing a leading role in making the Bradford Science Festival and the new Yorkshire Games Festival successful and sustainable parts of the city’s cultural calendar. Ultimately the decision to transfer the RPS collection is just one of a series of decisions made based on an assessment of the series of contexts that I hope this essay has illuminated. While there are dominant narratives that shape our current political moment, we had to make positive moves in the face of funding cuts. Instead of a museum starved of resources, retreating into itself and mothballing significant holdings, we have chosen to become a museum actively engaged in shaping our collections, ensuring their accessibility and use and deeply engaging with the people who live in Bradford, the city in which we are based.

Tags

Footnotes

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Ford: “Oh I think it’s got to be. And one has to be fair, you know museums are suffering. This government does not give lots and lots of money to museums, they’re all suffering cuts. The director of the Science Museum three years ago said if the government keeps cutting my funding I will not go on running four second rate museums, Bradford will close because it has the least visitors, and costs the most per taxpayer. Well sorry, but in the early days of the Museum it not only got more visitors than any museum outside London, it beat every museum except the top five in London.” http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b072hlwg Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text