Cosmonauts: Birth of an Exhibition

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/160508

Keywords

Cosmonauts, Cultural, Korolev, Russia, Science Museum, Space exploration, Spacecraft, Vostok

Introduction

The Science Museum has a rich tradition of exhibitions and galleries devoted to space exploration. Over several decades they have featured and highlighted examples of space hardware – rockets, satellites and spacecraft. The displays have dwelt on the technological and, sometimes, the scientific, with little consideration of the social, let alone of any cultural contexts in which the technology might be located. The Cosmonauts: Birth of the Space Age exhibition (2015) challenged this trend with an exposition that, while including uniquely historic space artefacts, situated them firmly and visibly within a far broader treatment of a nation’s interest in space. Recent scholarship had emphasised the role of the cultural in the emergence of Russia’s fascination with space and this was self-evident during a series of curatorial visits to Russia to research the exhibition. Would such a holistic representation of Russian space flight and its origins deliver the exhibition’s ambitious objective of attracting ‘large numbers of visitors’ and drawing ‘superlative comment’?[1] This paper presents the thinking behind and ambition for Cosmonauts: Birth of the Space Age. It relates this both to the Science Museum’s own history of space exhibitions and crucially to an evolving body of scholarship that is seeking new perspectives, principally of the social, the artistic and the cultural, from which to view and interpret Russia’s launching of the Space Age in the late 1950s. It refers to specific examples of this broader, inter-disciplinary approach in the exhibition and how this in turn was on occasion an emergent exercise where the final forms of the messages conveyed were contingent also on an established dialogue between the curatorial and design teams.

A major exhibition

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/160508/001Cosmonauts: Birth of the Space Age would be one of the first of a new series of major temporary exhibitions developed by and staged at the Science Museum. Specifically, the exhibition would set out to remind those aware and to inform those that were not of the early years of space exploration when the Soviet Union dominated the headlines (from c.1957 and the USSR’s launching of the first Sputnik satellite to 1966 and its first soft landing on the Moon of the remotely controlled spacecraft, Luna 9). This was a time when the United States appeared to be struggling with its own space programme; a period all but eclipsed for some by the magnitude of the Apollo Moon landing missions that followed at the end of the 1960s. Apollo dazzled and dominated the television and the press, a supreme technological and organisational achievement, supported by an equally effective campaign of promotion and publicity by the National Aeronautical and Space Administration (NASA). The Moon landings etched a powerful public memory of space exploration highlighting American achievement and almost excising the Soviet successes that had preceded it.

The exhibition would therefore ‘be revelatory: artefacts and images from the Russian space programme, for so long eclipsed by the American, will be displayed in the United Kingdom for the very first time; the stories of the people and personalities behind the space missions, so long hidden from the world, will be told’.[2] Its proposal emphasised the authenticity of the objects to be displayed: ‘Headlining will be a remarkable high-impact collection of real space hardware including flown capsules, rocket engines, flight spare satellites, probes and landers.’ Significant as these artefacts would be the exhibition would not be solely ‘a simple parade and revelation of technologies and technocratic achievement’. The exhibition would include also ‘vivid threads and perspectives from the visual and decorative arts that help place Russian space activity in a wider cultural context of the nation’.[3]

This addressed further but focused more accurately on an implicit, existing Science Museum objective of situating science and technology in a broader and more relevant social setting; one that would relate to potential Museum audiences, groups that traditionally had felt remote and disconnected from scientific and technical subjects. However, it reflected also a growing corpus of Soviet and Russian space history scholarship which was moving the focus on from the received accounts that emphasised the technological and the political – usually as inevitable outcomes of post-Second World War confrontation between east and west, and towards studies of what had been a far deeper and more sophisticated relationship of the Russian peoples with the cosmos. Similarly, concerns had been added over the traditional displaying of space artefacts in museums; Durrans, for example, argued ‘that both public and scholarly understanding of space is poorly served by technological bias…social context needs to be brought into the picture’ (Durrans, 2005). In respect to the locale of the museum he added specifically that it ‘need note only that space serves as a medium for expressing a range of social, corporate and personal interests, and that this happens both despite and because of space science, and always in close association with it’.[4] He was, in effect, reminding us that the spectacle and technological blaze of space exploration was rooted in very terrestrial activities and priorities within a broad community of social actors.

Collins maintained attention on the role of war in the eventual development of space technologies, suggesting such artefacts are, ‘for the most part, products of a particular milieu – the Second World War, the Cold War and the emergence of state-sponsored big science and technology products’, but highlighted also moves in the scholarship away from the geopolitical and towards more considerations of the role of the local to ‘shift the emphasis of the [space] programme history away from high-level politics and toward the multi-faceted terrain of ‘ground-level’ engineers and managers’ (Collins, 2005, p 3). This trend was illustrated well in the post-Soviet studies of the nation’s space designers and engineers – often auto/biographical – that drew aside the veil of state propaganda and myth to reveal previously secret details of how they worked within the constraints of state practice and priority.[5]

More significantly for the Cosmonauts exhibition and its perspectives and priorities, Siddiqi, Maurer and others had been looking in far greater detail at the cultural roots and manifestations of Russia’s interest in space, showing how it extended back through the twentieth century, well into the nineteenth, involving many thousands of citizens ‘from the ground up’; their interest and activities part of a distinctive ‘bridging [of] imagination and engineering [that was] mutable, intertwined and concurrent’ (Siddiqi, 2010).[6] Far from being entirely state-driven and inevitable, Russia’s exploration of space rested also on bedrock of social and civil involvement that long-pre-dated Sputnik.

All of this new scholarship would both inform the intellectual thinking of the Cosmonauts exhibition’s content and narrative structure but also help validate the Museum’s broader aspirations ’to make sense of the science that shapes our lives’;[7] of relating it more closely to visitors unfamiliar with or intimidated by the seeming remoteness of the subject.

Cosmonauts and Science Museum displays of space exploration

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/160508/002In relation to the Science Museum’s own exposition of space exploration over several decades, Cosmonauts: Birth of the Space Age would be a mix of the Museum’s traditional approaches and of novel ones. It would maintain an occasional but long-standing practice of displaying historically significant, often visually intriguing, flown space artefacts.[8] This began in the 1960s when American space capsules were exhibited in temporary stand-alone displays at the Museum. Gouyon demonstrates how these exhibitions established a Museum methodology, if tacitly so, of ‘historicising what was then “a new field of scientific and technological enquiry” and, adopting a theory of display first mooted by a Museum curator in the 1950s: exhibiting a “star object that draw’s visitors’ attention”’(Gouyon, 2014). And yet the Cosmonauts exhibition would seek also to convey a deeper understanding of Russia’s relationship with space that would take it well away from the archetypal space display of the Science Museum.

Space displays at the Science Museum

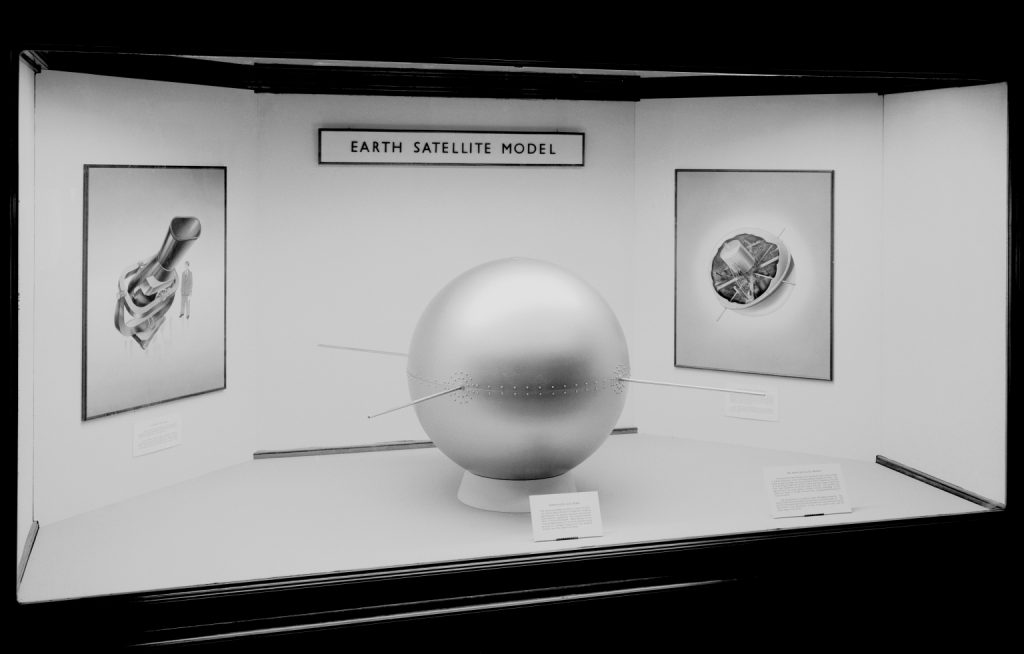

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/160508/003The first major permanent gallery devoted to space exploration had not been opened until 1986 but followed a succession of smaller and temporary displays from 1957 onwards that had established the Museum as a centre for the public’s interest in space exploration.[9]

The exhibits were populated in the main with small numbers of scale models of space launch vehicles and also, in the first permanent site for a space-related display on the third floor of the Museum, a selection of British rocket engines relating both to aircraft assisted-take-off and to missile development – technologies applicable to space exploration but in this case, not of space exploration (Millard, 2010).

Real spacecraft were difficult to acquire and display, with notable exceptions being the engineering models of the early British satellites Ariel 1 and 2 and then, in 1962, 1965 and 1976 respectively, the flown US space capsules Mercury Friendship 7, Mercury Freedom 7 and Apollo 10.

Friendship 7 – the spacecraft in which John Glenn became the first American to orbit the Earth – was displayed for just two and a half days but attracted 25,000 visitors. Astronaut Alan Shepard’s Freedom 7 formed the centre piece for a larger temporary display that remained for over six months and was seen by almost 350,000 visitors (Gouyon, 2014). The Apollo 10 command module touched down in the Museum in January 1976 after a European tour in which it had suffered significant damage during its public displays.

This loan from the then National Air Museum of the Smithsonian Institution, to be renewed every few years, became a centre piece first of the Museum’s interdisciplinary gallery Exploration (1977) and then, on the same ground floor site of the Museum, its first permanent gallery devoted entirely to space exploration (The Exploration of Space, 1986).

The Exploration of Space adopted a magazine-style format which both historicised objects and used them in support of technical explanation.

It was divided into named sections dealing with ‘History’, ‘How Rockets Work’, ‘What Rockets Do’, ‘Britain in Space’, ‘Europe in Space’, ‘Living in Space’, ‘Man in Space’, ‘How Satellites Work’ ‘Robot Explorers’ and ‘Remote Space Astronomy’, ‘Local Space Science’, ‘Satellite Communications’ and ‘Remote Sensing’. The ‘Man in Space’ section included the Apollo 10 command module as key exhibit set opposite a full-scale model of the Apollo 11 lunar module on a mock lunar surface and nearby to scale models of the Soviet Vostok and US Mercury spacecraft and launching rockets. The supporting texts and graphics carried a descriptive narrative of what the missions were and when they occurred.

Apollo 10 was moved to the new Making the Modern World gallery in 2000, one of over two-and-a-half thousand of the Museum’s most historically significant objects gathered together in one large space. Here it now stood alone as a self-referential relic near to other unrelated artefacts (including the original EMI brain scanner, Flying Bedstead experimental aircraft and an early Cray supercomputer). It occupied a zone of the gallery dealing with post-war big sciences and technologies (Defiant Modernism). While elevating (literally) Apollo 10 onto its own historic pedestal, its minimal interpretation rendered it hidden to many visitors and especially those unfamiliar with the shape and appearance of a flown Apollo command module. Nevertheless, the spacecraft had long been one of the Museum’s most acknowledged objects, particularly during the 2000s when the Museum’s Press and Curatorial teams used the spacecraft regularly as either the subject of Apollo-related anniversary stories and gallery activities or as a focus for space-orientated news coverage in search of a suitable visual backdrop to anchor the news item and its presenter. It was Apollo 10’s authenticity and historicity (one of nine spacecraft that took astronauts to the Moon in the last century), its physicality and presence, that resonated with visitors during the curatorial talks and activities staged around the spacecraft. For many it was being in close proximity to the actual craft that had taken three astronauts around the Moon that justified their visit. For the fortieth anniversary of its 1969 mission the barriers surrounding the spacecraft and Perspex plate covering the hatchway were removed, allowing visitors under heavy supervision by Museum staff to get still closer and also to look inside at its consoles and controls. Supplementary information was provided for the visitors to consult including scale models of the Apollo Saturn rocket and spacecraft, printed drawings of the module’s main consoles and copies of contemporary magazines and newspapers from the 1960s.

It was during the initial planning of this event in 2008 and the focusing on the historicity of an authentic space artefact that my thoughts first turned to bringing a real, flown Vostok spacecraft to the Museum in time for the fiftieth anniversary of the first human spaceflight carried out by Yuri Gagarin in Vostok 1. The display would be equivalent to Apollo 10’s in Making the Modern World, addressing a perceived appetite of visitors to become intimate with an historic event by getting close to the ‘icon’. Proximity would be sufficient. On-gallery interpretation would be secondary. And yet as plans to bring a Vostok spacecraft to the Museum evolved so too did the scale and nature of the future display’s intellectual underpinning. The change reflected the impressions gleaned during my visit to Russian space locations in 2009 and the near coincidental scholarship that was now directing historians’ attention towards far broader and older cultural interpretations of Russia’s relationship and eventual exploration of the cosmos.[10] The two elements were mutually inclusive. My experiencing of Russian ways and institutions, of the land and its people, was every bit as important as rehearsals of the scholarly and the academic, in outlining a vision for the exhibition and what it was intended to achieve.

Cosmonauts: Birth of the Space Age

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/160508/004Cosmonauts confronted the visitor entering the exhibition immediately with an unconventional display of space.

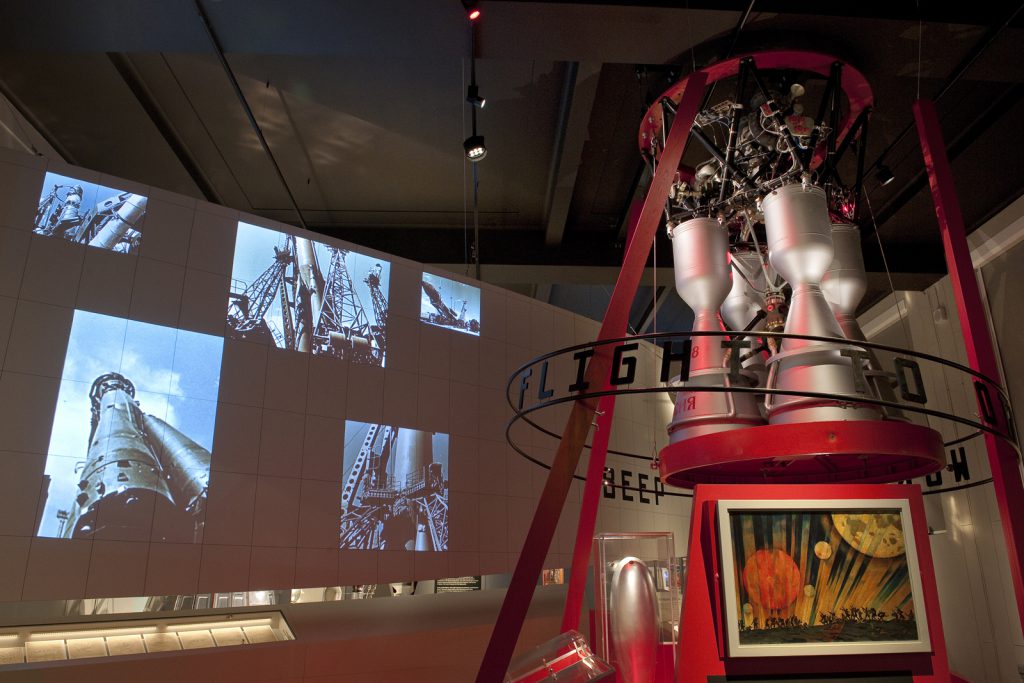

Yuon’s New Planet (1921), the first depiction of the Russian revolution of 1917, sat beneath a vast, four-chambered rocket engine. The engine was an RD-108 as used on the central stage of all Soviet and Russian R-7-based launch vehicles from the time of Sputnik through to the Soyuz launches of the present. New Planet shows the people in tumult, in celebration, in awe, perhaps in fear, of the new Communist society, one that would lead in the creation of a new world order. It is not clear whether the red planet Yuon shows in the background of his painting is this new Earth or the old Mars. This juxtaposition of genres forewarned the visitor to the exhibition of the type of space displays and narrative that would follow – combinations of the technological and the cultural; a melding of the technological display and the artistic. But it presented also the intellectual grounding of Cosmonauts where ‘imagination and engineering [are] mutable, intertwined and concurrent’. It carried an implicit message too that the events of 1917 were relevant to what happened four decades later when the Soviet Union launched the Space Age with the first Sputnik satellite. This entire first section of the six in the exhibition acted as a historical overture to the space programme that followed later in the century.

This relationship of the rationalistic and the imaginary was emphasised with the nearby design of Georgi Krutikov in 1928 for an orbiting apartment complex. He was thinking of solutions to the Moscow housing shortage of the 1920s. A tear drop-shaped shuttle craft would ferry the citizens to and from their space homes.[11] Alongside the architectural designs of Krutikov were two works from the Suprematist school of early Russian avant-garde. Ilya Chashnik’s Suprematism (1922–23) is an example of the movement’s abandonment of the materialistic in favour of the totally non-objective; where the artist’s feeling is all and expressed in the simplest of forms, shapes and colours. Black represents the immeasurable universe, and white stands for humanity as a source of cosmic energy. Ivan Kudriashev’s Disjunction (1926) gives visual expression to scientific notions of velocity and speed. Kudriashev was influenced by Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, his near neighbour in the town of Kaluga and pioneer of cosmonautical theory. His calculations and depictions of space flight predated the space era by decades. Tsiolkovsky, in turn, was rationalising Nikolai Federov’s cosmist philosophy, a belief that humanity’s salvation and destiny lay in space; deliverance for all, living and dead, that could now be achieved with science and technology.

These opening displays in Cosmonauts introduced a far deeper treatment of (Russian) space flight history and one of its key players than had been the norm in previous Science Museum exhibits.[12] Tsiolkovsky was presented to the visitor but rendered more real and accessible: his mystical cosmist influences, his simple drawings of weightlessness, even his deafness (a displayed hearing trumpet one of many he made as his affliction grew more serious). The exhibition did not acknowledge the post-Soviet reassessments of Tsiolkovsky that revealed his far from straightforward relationship with state and, in particular, his posthumous state-sanctioned revival during the 1950s. Space advocates such as missile Chief Designer Sergei Korolev had taken advantage of the ‘prevailing codes of Zhdanovshchina – a period of extreme nationalist sentiment – by canonizing the late Konstantin Tsiolkovsky as a great scientist in the Russian tradition’ (Siddiqi, 2010). His undoubted contributions to cosmonautics were being repurposed, and to a degree rewritten, to further the cause of space exploration as a legitimate and necessary state activity. His hagiography was entirely typical of that afforded other leading members of the Soviet space aristocracy and not least the cosmonauts themselves. Lives and biographies were smoothed and honed in the service of heroic space achievement by the Soviet state and people.

Korolev himself, referred to publically only as the ‘Chief Designer’ during his lifetime, was portrayed subsequently as a remarkable individual who more than anyone steered the Soviet Union towards the stars. Yuri Koroelv’s Chief Designer (1969), occupying an entire wall of the exhibition, epitomises his namesake’s elevation to mythical status; the white-coated Korolev standing proud against a background of industrious technicians working on the Luna 9 spacecraft. Above, a fiery Vostok capsule hurtles back to Earth.

There is little doubt Korolev was a remarkable individual able to harness disparate collections of state institutions – including the scientific and political elite – in a drive towards beating the Americans into space. What the officially sanctioned histories of Soviet times did not acknowledge, even after his death in 1966, were the details of his relationships, good and bad, with fellow designers like Valentin Glushko, designer of the RD-108 engine, and with Vladimir Chelomey; the competition and squabbling between them; the political manoeuvring with premier Khrushchev – whose son worked for the Chelomey design bureau; the mutual antagonism of Korolev and Glushko that dated back to the late 1930s when Glushko’s testimony against Korolev contributed to the latter’s arrest and imprisonment in the Siberian Gulag. Near to the massive Chief Designer in the exhibition sat Korolev’s aluminium drinking mug, the only possession he brought with him when he was moved from the Gulag back to Moscow.

The display was acknowledging both Soviet and post-Soviet interpretations of the Korolev figure by bringing the portrait and the mug together, echoing also Gerovitch as he refers to the boundaries between myth and memory remaining blurred, so much so that there is no longer a choice between the two but rather ‘different versions of the myth’ (Gerovitch, 2011).

Display ambiguities featured elsewhere in Cosmonauts. Just in front of the Voskhod 1 descent module was the mission commander Vladimir Komarov’s woolly hat, loaned to the exhibition, like Korolev’s mug, by Natalia Koroleva, daughter of Chief Designer Korolev.

The two items were on the one hand following a well-established tradition in Soviet and Russian space exhibits of displaying relics of the famous and of the heroic; items from their work, sometimes a recreation of the work space itself – Tsiolkovsky’s workshop, Korolev’s office. With Komarov’s hat in close proximity to the spacecraft he commanded – Voskhod 1 – the exhibition presented another blurred message of spectacular spacecraft of triumphant mission and vulnerable person on board. (The three Voskhod 1 cosmonauts had only thermal garments to wear, including the hats, as there was no room for space suits in what was essentially a repurposed Vostok spacecraft, which had been designed to carry one person only.) Nearby some simple text marked Komarov’s death on the Soyuz 1 mission of 1967, and also Valentin Bondarenko’s during a ground test fire in 1961. Above towered Georgy Frangulyan’s Space Brothers (1979), a two-man cosmonaut crew, hands raised in a final wave of farewell before boarding the spacecraft. The heroism is of a dangerous mission; an implicit message of glorious eternity and immortality, two men setting off bravely into the unknown. In the context of its exhibition setting, however, Frangulyan’s monumental sculpture signified the courage and the tragedies of the early space age.

The exhibition’s final room carried one object and further ambiguity. A single human form – a Tissue Equivalent Mannequin, reclining on a metallic framework – was the only object displayed. It had been intended originally for an earlier section of the exhibition (Secret Moon) that looked at the Soviet manned lunar programme of the 1960s and 70s, the USSR’s response to Kennedy’s Apollo challenge, but only admitted to during Perestroika and Glasnost under Premier Gorbachev in the late 1980s. Like the lunar lander displayed in that section – an engineering model used to train the cosmonauts and brought from Star City to the Moscow Aviation Institute in the early 1970s – the mannequin was an authentic object from the Moon programme. It would have been included as material evidence of a previously denied attempt on the Moon.

Yet alternative translations and meaning of such an artefact became crucial in the case of the mannequin. It had been flown around the Moon and back to Earth on the Zond 7 mission of 1969, the mannequin’s embedded radiation detectors gauging the distribution of harmful ionizing particles that would fall on a real cosmonaut travelling on a similar trajectory around the Moon. In the exhibition’s closing room, where it was finally moved to, that description was retained on the accompanying label but now set against the greater ambiguity of its display setting. The scene was intended to move the object from one of fact to one of speculation. In this room the figure was both of humanity yet not. It has limbs and a body, its face is cast in the image of Yuri Gagarin (who had died in 1968). Yet it appeared cold and metallic, a burnished gold. Its arms and legs articulated as if an android. The figure appeared both robotic and human – a Maschinenmensch from the space age.[13] It had been flown around the Moon as an avatar, an emissary, a representative of the human race for whom the mission was deemed too dangerous for a real cosmonaut.

The room’s ceiling held a rectangular, glowing red breach; a feature redolent of Ilya Kabakov’s The Man Who Flew into Space from His Apartment, but also of a red destination in the sky.[14]There were hints about it of Kubrick’s monolith from 2001: A Space Odyssey. An azure hue washed around the mannequin’s crystalline case, suggesting shades of Carl Sagan’s Pale Blue Dot.[15] On the wall could be read Tsiolkovsky’s attributed words of 1911 stating, or predicting, that humanity will not stay forever in Earth’s cradle. The room was indeed about going to Mars but, with the increasingly sophisticated robotic craft exploring the Solar System, implying that there was no certainty that humans would ever get to the red planet when vicarious exploration would become so much more capable. Perhaps it remained as a dream of the future, much as it had been for those visionaries, artists and enthusiasts in the early decades of the twentieth century.

The contingency of display

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/160508/005The mannequin represented also the exhibition’s contingency of display; the inevitable selectivity and bias implicit in the exhibition owing to whatever items were available to the curatorial team and those alternatives that were not. Basic display themes and messages had been identified early in the exhibition’s planning (and most were retained through to the opening) but were still dependent on the locating of items with which to illustrate those themes. The need to include artistic representation of Russia’s relationship with the cosmos was identified and then duly delivered by way of the curatorial team’s prior knowledge of and subsequent visits to the Tretyakov Gallery (where my Cosmonauts curatorial colleague Natalia Sidlina’s previous work experience and contacts were invaluable) to choose appropriate works. But even then, the selection had to be approved by the Gallery and the highly desirable and ultimate example of cosmic suprematism – Malevich’s Black Square (1915) – was unavailable for loan.

The Tissue Equivalent Mannequin’s inclusion, however, had not been planned, nor as has been explained above, was its eventual displaying as artefact straddling the historical and the futuristic, the known and the unknown, the human and the artificial. This section, perhaps more than any other, reflected also a strength and rapport between the curatorial and design teams that had been established early in the project. This relationship moved swiftly from initial exchanges of information on the details of individual exhibition objects and assets to discussions where the conviction, context and emotion expressed were every bit as important as mere confirmation of the facts and statistics of exhibition content.

The mannequin had been encountered, almost by chance, during my first visit to Moscow for the project in September 2011 when the Museum director Ian Blatchford noticed it on the floor and almost hidden behind a door in the space gallery of the Polytechnic Museum.

Its striking appearance belied the significance of it as a historic, space-flown object which only became apparent when I knelt down to read its small label. Its power to imply fundamental messages about the future of human spaceflight came only after dissatisfaction with the planned ending of the exhibition (focusing on the Mars 500 research programme) and the subsequent conversations with the design team about how its inherent ambiguity could be interpreted in the nature of its display.

Towards the culture of space exploration

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/160508/006That this exhibition’s aspirations were largely achieved would appear to be confirmed by the reaction of commentators and visitors alike: ‘Colossal’ – The Telegraph; ‘Must see’ – Londonist; ‘An outstanding collection’ – New Scientist; ‘Gripping’ – The Observer; ‘See this show and be uplifted, transported, taken out of this world’ – Nature; ‘You will leave Cosmonauts with a different view of humanity’s place in the cosmos’ – Professor Brian Cox. The public reaction was equally enthusiastic and with a month still to run the exhibition had already welcomed over 100, 000 visitors. Typical comment on social media included: ‘Superb exhibition. You should all go. Now. Today’. @little_frear; ‘The Cosmonauts exhibition at the Science Museum is completely fascinating. I learnt so much.’ @jenimrose; ‘Holy Poop, it is so good.’ @coollike.

There is a question now of whether the success of Cosmonauts signals the need for an equivalent approach in other, future displays on the origins and history of space exploration. That the Russian experience is a singular one, emerging from a rich mix of the social, the artistic and the cultural is true but might surely also be the case, in respective ways, for narratives of other national and, indeed, international relationships with the cosmos.

Tags

Footnotes

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text