Issue 21 Editorial

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/242104

Keywords

Cambridge University, Editorial, Professor Stephen Hawking

In this edition of the Science Museum Group Journal a special collection of four articles explores some of the most significant scientific acquisitions made in recent decades, that of Professor Stephen Hawking’s office at the Science Museum Group and the papers of Professor Hawking at the University of Cambridge. The collection reflects the objects and archives in the Department of Theoretical Physics and Applied Mathematics at the University of Cambridge at the time of Professor Hawking’s passing, and they give a unique insight into the routines and practices in his life, and the collaborators with and carers for this remarkable man. They allow researchers, scholars and curators not only to delve into the practices of theoretical physics in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, but to explore the changing nature of scientific and academic collaboration and communication, and the realities of what it means to live with a major degenerative disease whilst also being a celebrity.

As Head of Collections at the time of the acquisition (and guest editor for these papers) I know from experience that such an acquisition of the possessions of a major national figure to a museum doesn’t just happen. It requires gentle persuasion and prolonged negotiation to ensure that the collection is preserved for posterity and for the nation. It also takes great insight from those who cared for him and have responsibility for his estate to have an eye on the longer-term legacy of such an individual, as they are also mourning their own loss. And for this carefulness and consideration to the legacy of Professor Stephen Hawking to the country, to science, but also for future curators and historians, the Science Museum and Cambridge University are enormously grateful.

Even once the legal transfer is complete, there is the need for decades of research to understand the significance of the contents of Stephen Hawking’s office, the meanings that the objects and archives held for Hawking and his collaborators and colleagues, and the potential for this collection to be understood and interpreted in new ways for and by the public. This issue begins that journey, as we reflect on aspects of both collections, the ways they have been mediated in their acquisition, and the stories they might tell in the future.

In these papers we seek not only to explore what the collection shows about the life of a renowned scientist and a global celebrity, but also how it provides insights into the ways that theoretical physics has been conducted over decades. We also reveal some of the often hidden work that goes into the acquisition, cataloguing and understanding of a new museum or archive collection. Society tends to celebrate the visible products of often decades of curatorial and archival research – the exhibitions and galleries that result for the public – but they rarely explore the decisions that are made along the way, such as choices about what is, and is not, acquired and the narrative threads that are explored whilst others are ignored.

In this way the collection of articles in this special edition might simply be summarised as: ‘What do curators and archivists do all day?’ Not only providing insights into the life of one of our most renowned scientists, it also considers the practical implications of acquiring the physical, digital and archive legacy of Stephen Hawking, and the resulting opportunities for understanding the nature of scientific, curatorial and artistic work.

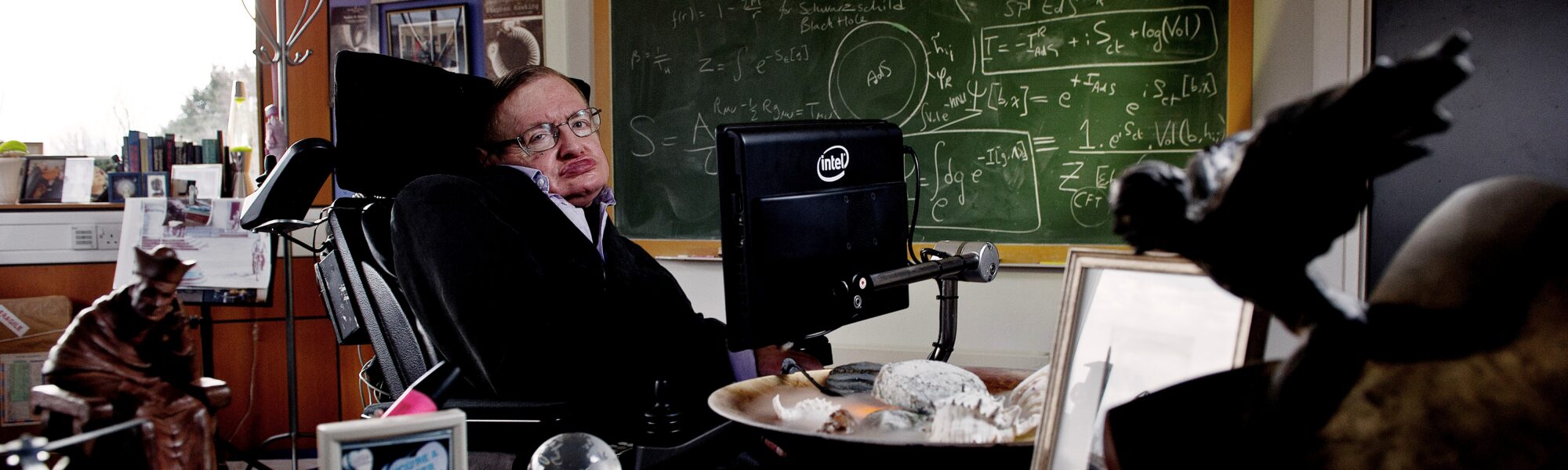

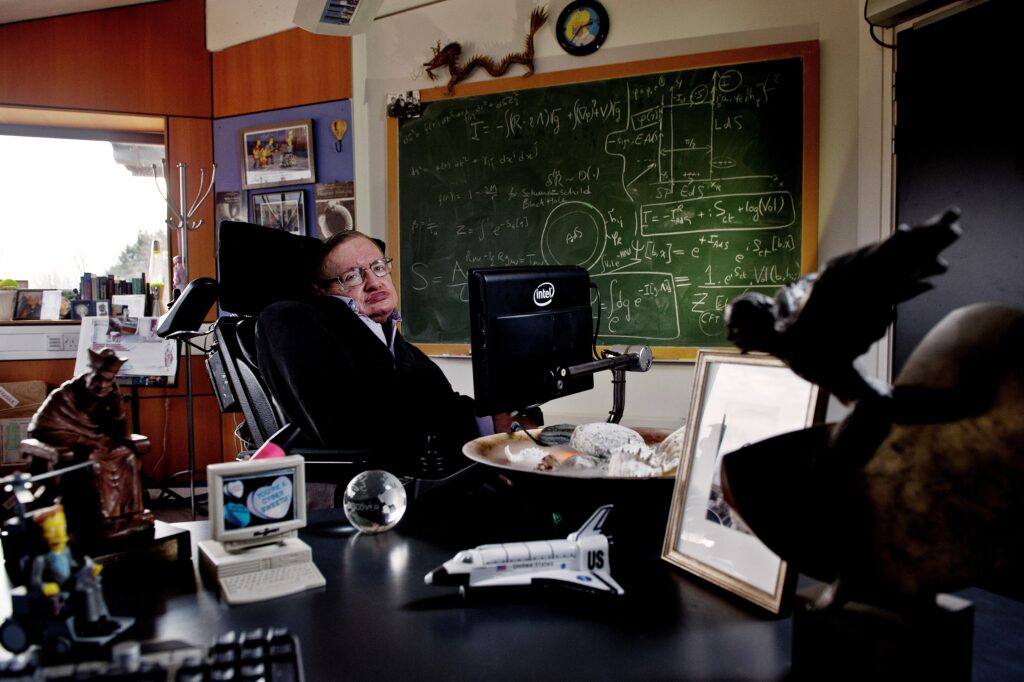

In the first paper, I and Alison Boyle discuss the curatorial work and thinking behind acquiring the office, showing how the collection not only sheds light on the life of a scientific celebrity, and the nature of collaborative scientific work, but also reflecting on the process of acquisition and the weight of curatorial responsibility we felt in acquiring it – as project leads we were very aware that we were ensuring that range and detail of the objects in Stephen Hawking’s office were captured for posterity, opening up new pathways for research in the history of science and supporting a multitude of potential future interpretative paths in galleries and exhibitions.

In a separate paper Hannah Redler-Hawes describes the experience of navigating the boundaries between science and art as she curated an international exhibition in Leuven, Belgium with the cosmologist and Hawking collaborator Thomas Hertog. Featuring objects from the office alongside the work of other celebrated physicists and of contemporary artists, she highlights the complexities of traversing artistic and scientific theory, requiring both curators to be adept at uniting the intellectual with the theatrical, the experiential with the philosophical, all within one non-traditional exhibition space.

A detailed object biography of the now famous blackboard in Hawking’s office is provided by Juan-Andres Leon. Resulting from the collective doodles of physicists at a conference, and preserved by Stephen Hawking’s secretary, the blackboard was subsequently displayed in his office, then in exhibitions in Leuven, Belgium and in South Kensington, London. Highlighting the collective and social nature of research, with Hawking’s own sense of fun and humour, the blackboard has also become a symbol of scientific success and failure, and the power of museums in exploring both, as the ideas it contains around supergravity have been superseded.

Finally, Katrina Dean and Susan Gordon discuss the mediation of the paper and digital archive acquired by Cambridge University Library. They explore the changes in the ways that Hawking communicated his scientific ideas over time, how he worked with others (including scientists and Graduate Assistants) and his use of different technologies to do this. They also reflect on their own practice as archivists, navigating between digital technologies and paper artefacts within the collection, and their desire to eventually unite digital files within the Collections (these were not included in the original Acceptance in Lieu offer).

There is still much work to be done in terms of understanding the Hawking Collections at the Science Museum and in Cambridge, and in many ways this work will never be complete, as each succeeding generation will find fascinating new ways of appraising the Collections and new interpretations of Stephen Hawking’s work and life through the lens and interests of their own time. In this set of papers, I hope that we give a sense of the opportunity here, not to celebrate scientific genius, but to highlight the more interesting nuance and complexity of working as part of a network of science collaborators, of living with disability, and of negotiating the role of being a husband and a father whilst being a scientist continually in the public eye.

This issue looks at issues of curatorship, research and audience engagement in another area too. In ‘Objects of the Mind’ Tim Snelson et al discuss a collaborative research project between curators at the Science Museum and National Science and Media Museum and academics from the Universities of East Anglia and Manchester. The project allowed academic researchers to tap into public interest in objects (from the museums’ mental health and film collections) and in popular films (supplied by partners StudioCanal) to engage new audiences with research on the interactions of psychiatry and cinema. From the museum perspective, the research asked new questions and told new stories about the objects and helped foster cross-collection dialogue between medicine (Science Museum) and media (National Science and Media Museum) collections. The paper discusses a range of events, activities and outputs the authors delivered within the project, but it focuses particularly on three new films (which can be seen within the article) that (re)combine museum objects, feature film clips and expert interviews to tell new stories about and across the collections.

Exhibition and book reviews add to the issue, which is completed by a tribute to the late Jim Bennett, historian of science and Director of the History of Science Museum in Oxford, who also contributed so much to the Science Museum and to this journal as an advisor and friend.