Making museum research more visible: Open Access in the GLAM sector

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/252304

Abstract

Open Access paradigms have changed how academic scholarship is published and disseminated, creating a new model for how research is shared. But how do these paradigms map onto museum research? This question is particularly pertinent when larger numbers of funded research projects include, or are led by, museums. This article considers some of the affordances and challenges of using Open Access principles and technologies to make visible the multifaceted modes of research that take place in a museum setting. Using the Science Museum Group as a case study, it focuses on how repositories offer one means to make research conducted in museums more accessible, while also broadening definitions of what a research output is. With the focus hitherto more on images and collection items, here we expand into the realm of exhibition and gallery outputs – the content which museums produce to narrate their collections’ stories and engage audiences. Many of these outputs may have been designed to have an ephemeral, physical lifespan, but through platforms such as repositories they can gain a digital afterlife, serving a new purpose as learning resources, research data, or indeed a record of curatorial and museological practice. The article ultimately argues that Open Access principles can aid museums (and the wider GLAM sector) in their mission to be transparent organisations for wide-ranging audiences.

Keywords

digital humanities, digital technology, digitisation, museology, Online repository, open access, repository, scholarly publishing

Introduction

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/What is Open Access?

Open Access (OA) is now a familiar and widely implemented practice in scholarly publishing in the United Kingdom (and worldwide), with its roots in the Budapest Open Access Initiative (BOAI) in 2002 (George, 2024, p 1117). The principles of OA rest on the idea that academic research – in particular, research funded by public money – should be made available beyond the academic community, facilitating its use and interpretation by others. This, it is argued, supports better research, makes research more equitable, and also makes research better value for money (see Figure 1). OA principles have been applied in movements such as ‘open science’, which call for making both research papers and the data on which they are based freely available online (Vicente-Saez and Martinez-Fuentes, 2018), and the humanities disciplines, too, are now shaped by the OA model (Eve, 2013; Mandler, 2013). The implementation of OA through policy and practice does, however, vary across different national and institutional contexts, and often the process of implementation has been uneven.

For the sake of this article, which focuses on a UK context, we can look to the 2010s as a key moment when government policy began to reflect the call for more open research. For example, in 2012, recommendations were implemented from the Finch report. This report, which was based on a working group commissioned by the coalition government and chaired by Dame Janet Finch, advised that publicly funded scientific research ‘should be made available for anyone to read for free’.[1] More recently, United Kingdom Research and Innovation (UKRI) mandates, effective from 2022, state that certain research outputs generated from their funding – namely, journal articles, book chapters and monographs – must be made available OA upon publication.[2]

These changes in practice have now led to new models for how such outputs are paid for, with authors – or their institutions – frequently required to pay article processing charges (APCs). Though these pay for the output to be made freely available (i.e., no longer behind a publisher’s paywall), they can be very expensive to fund at the outset (Butler et al, 2023). A model named ‘Green Open Access’ has thus been developed to allow for articles published behind a paywall to be made available in an earlier format – e.g., the accepted manuscript without formatting or images – online in institutional repositories (George, 2024, p 1117). Repositories, therefore, have become a vital piece of the online academic landscape, with most universities and research institutions using them to store and catalogue their research outputs (see, for example, Callicott et al, 2016; Jain, 2011; Marsh, 2015).

But OA stipulations do not only affect academic research taking place in universities – in the UK, Independent Research Organisations (IROs), of which many are galleries, libraries, archives and museums (GLAMs), can also lead funded research projects. These IROs often do not have the same large-scale information systems infrastructures that universities do, including systems like a repository, to easily catalogue, document and preserve their research outputs. Furthermore, the kinds of research conducted in a GLAM setting frequently take on a different character to that in a university, with outputs ranging from the traditional – such as journal articles and book chapters – to the non-traditional – including exhibitions, reports and digital audience engagement. Indeed, it could be said that within a museum, those definitions are reversed – what the scholarly community might see as traditional (journal articles and monographs), museum professionals see as non-traditional, or perhaps above and beyond the research they conduct daily. And, as initiatives such as the ‘Hidden REF’ show, the work of academic research is becoming increasingly blurred between the traditional and non-traditional (Derrick et al, 2024).[3] Nonetheless, for the purposes of this article, we will home in on museum research. As Perkins notes, ‘museums hold enormous amounts of information in collections management systems and publish academic and scholarly research in print journals, exhibition catalogues, virtual museum presentations, and community publications’ (Perkins, 2001, p 2). How IROs meet the stipulations of their funders offers, therefore, a challenge: How far can OA paradigms born in the academic sector be mapped onto museum research? What does OA mean for museums?

Mapping OA onto GLAM research

As Wiedemann et al have observed in a German context, the need for transparency has not only affected the sphere of academic research: ‘More openness in the provision of publicly funded content, such as that of museums, has recently become an important public issue’ (Wiedemann et al, 2019, p 194). The question of openness has already found its way into the GLAM sector in the UK, mostly in relation to images and collection items. Groups such as OpenGLAM were set up to encourage GLAM institutions to make collections data and images freely available online with copyright licences that allow them to be used by others. Glasemann writes that ‘the movement generally referred to as OpenGLAM builds on the premise that information and data should be shared openly’ (Glasemann, 2024, p 112). Many GLAMs have responded to such calls, with large-scale digitisation and cataloguing projects ensuring that museum collections are more accessible than ever before. The Science Museum Group’s (SMG) Collection Online is one such example of this kind of initiative, with images and collection data freely available online (though not for commercial use for the images, when a fee still applies). Some European and US-based museums, such at the Metropolitan Museum of Art,[4] have gone even further with collection images available to download on the most unrestricted licence, the CC0 Public Domain Dedication, which is often seen to be the gold standard for OA. UKRI have also designated large amounts of funding to research projects aimed at making collections more accessible, through initiatives such as Towards a National Collection (TANC). This included the SMG-led project Congruence Engine, which experimented with digital tools to link together national collections relating to energy, textiles and communications.[5]

Digitising collections and making them available is expensive and time consuming, which is why larger institutions have been more likely to find the resources to undertake these projects. However, wider digital initiatives have been assisting smaller collections to embrace OA, with projects like Wikidata and Wikicommons, and also Google Arts and Culture, which fund this kind of work. The GLAM-E Lab, a joint initiative between the Centre for Science, Culture and the Law at the University of Exeter and the Engelberg Center on Innovation Law & Policy at NYU Law, offers guidance to GLAM organisations that want to embrace OA principles. A recent toolkit produced by the Royal Albert Memorial Museum & Art Gallery with the GLAM-E Lab advises other institutions on why and how they make their collections available OA, making the business case that providing images for free might actually be more cost effective than trying to manage and monetise their use (Farmer and Wallace, 2024).[6]

Such discussions are reflected in recent academic literature on the impact of OA on the GLAM sector, which – for the most part – discuss the affordances and challenges of OA specifically for making collections data more accessible (Wiedemann et al, 2019; Kapsalis, 2016; Glasemann, 2024; Dupuy et al, 2015; Perkins, 2001). However, despite this burgeoning literature on the topic, Kapsalis correctly notes that it is ‘important to acknowledge that there is no universal consensus about the definition of open access, and among practitioners, much confusion persists about what constitutes open access’ (Kapsalis, 2016). We might contend then that these academic interventions represent only the beginning of an evolving discussion about what OA means beyond scholarly publishing, in particular for research-active organisations such as museums.

Thus, it is the intention of this article to broaden the scope of how OA principles are applied within museums – and by extension GLAMs – by considering how these institutions might make their non-collections-based research data more readily available and conceptualise definitions of what research in this sector looks like. As highlighted already, this is necessitated first of all by the premise that museums and other GLAM institutions with IRO status also receive funding, like universities do, to lead research projects and host doctoral students, and with the changes in OA from funders like UKRI, they too must make sure that certain outputs are available. It is the contention of this article that these changes for OA offer IROs – and museums more broadly – the opportunity to rethink what research in a museum context means and to think not only in terms of meeting funder requirements but how OA can help them fulfil their obligations to their audiences. This is especially pertinent when many museums have put forward in their strategies a need to broaden access to their collections and the knowledge tied to it. SMG, for example, in their latest strategy (2022–25), have made it their mission to be ‘open for all’, with digital expansion as one of the key tenets of how to achieve this.[7]

The enactment of OA principles depends, however, on the provision of suitable technological infrastructure. Previously, museum websites have offered one digital space for sharing museum research outputs, but merely uploading a file to a webpage does not allow for systematic cataloguing or the linking of material. Borrowing from the university sector, a response has been for museums to use repositories to upload and catalogue research outputs. Perkins defines repositories as ‘essentially network accessible servers offered by data providers’, which has ‘simple protocol records that contain metadata about its items (content). A repository may, optionally, organise its items into sets corresponding to its collections or other groups, thus allowing clients to harvest metadata records selectively’ (Perkins, 2001, p 3). Zenodo – the repository run by CERN – is a popular cost-free choice, for example, that anyone can access and use. However, a more bespoke shared research repository service, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) and managed by the British Library (BL), has now come into existence, with the specific aim to allow IROs to meet new OA requirements.

It was this service that SMG elected to join in 2023. As the team leading the population of the repository – and in consultation with our colleagues in Research & Public History, Libraries and Archives, and Curatorial – we saw an opportunity to utilise the shared research repository to not only meet the OA requirements of funders but also to deliver SMG’s goal to be ‘open for all’. Such an approach meant that it was necessary to dissect the definition of ‘research’ in a museum, conceptualising outputs as traditional academic ones and the more non-traditional ones that are the bread and butter of what museums produce (examples including object labels, exhibition panels, in-exhibition animations, to name only a few).

SMG’s research repository is now home to a range of research outputs, spanning traditional research outputs such as journal articles and PhD theses, and outputs that have hitherto not had an online home, including exhibition texts, object labels, animations, and other ephemera from past exhibitions and galleries at SMG. In this article, we share the processes we used to conceptualise and instigate the population of the repository, offering one model for how museums – but also other GLAM institutions – can approach the multimodal nature of the research they conduct while applying OA principles. We will discuss the challenges of such a process, particularly relating to the ephemeral nature of much of the content, quality checking, copyright, and the need to ensure institutional buy-in and comprehension of the usefulness of these efforts.

Ultimately, we argue that repositories allow museums to capture an aspect of what makes the research they do uniquely useful; museum research intersects collections, exhibitions, audience engagement, learning and academia. Committing to sharing more of the outputs where these manifest – beyond only collection images and metadata – will allow museums to be more transparent, making the knowledge and practices they produce shareable, archiving them for both current and future audiences. In very real terms, these resources can be used by museum professionals, university and schoolteachers, students, researchers and – which is the beauty of OA – unknowable audiences who might simply stumble upon the material through a search query.

Why join the British Library shared repository service?

As an IRO with several UKRI-funded research projects, SMG had to respond to the aforementioned UKRI OA policies for research publications, effective since 2022. While universities have repository systems embedded in their libraries and information systems, smaller organisations like GLAMs do not always have these resources. In response to both the UKRI OA policy and a lack of repository infrastructure in IROs, the AHRC has worked with the BL to build a bespoke digital storage facility for IROs to meet UKRI guidelines and share their research outputs online. In light of the cost and expertise required to build an in-house repository, SMG – with advice from the digital team – decided to join this shared repository scheme in September 2023. While SMG now have their own OA repository dedicated to its research outputs, it sits within a much larger shared scheme, as implied in the name, with other members including the BL, The British Museum, National Museums Scotland, Tate and the National Trust, thus situating SMG within this broader terrain of research-intensive GLAM organisations (Jain, 2011).[8]

In addition to its cost effectiveness – repositories bypass the need to pay the sometimes prohibitively expensive APCs, and the BL’s service is currently free – there were many other reasons why joining the shared repository service was a positive step for SMG:

- It allows SMG to better showcase the array of work produced by its highly research-active staff, whether UKRI funded or not.

- Once uploaded, the knowledge and record of work can be learnt from and easily shared with staff across the Group. This makes the repository a valuable digital resource for internal and external audience engagement.

- Beyond traditional scholarly outputs, the repository provides a space for research without a digital home, for example, exhibition texts, grey literature, etc. These can be minted with a Digital Object Identifier (DOI), making them easy to discover and cite, allowing SMG to create a direct link to their data (Uzwyshyn, 2016, p 18).[9]

- The repository can also accommodate multimedia content, e.g., recordings of lectures and talks, and material that is no longer deemed up-to-date enough or is too large for the website.

- It can be curated. It is possible to create collections and designate featured items. Research projects are listed as a collection and the outputs to that project are included. In this way, it brings together outputs that do not always sit together, and is a means to quantify them (Kapsalis, 2016, p 3).

Designing a methodology for the repository

To begin conceptualising what the repository would contain, we started by asking the question: What is a research output? The answer to this question depends on the type of institution that is asking it. In universities, research is academic in nature and largely consists of the writing and publishing of journal articles and monographs (though the OA movement calls for sharing the data on which these written outputs are based). In contrast, the type of research carried out in museums is different. It ranges from the traditional (journal articles and book chapters) to the non-traditional (exhibitions, conservation reports, audience engagement, etc). Yet, as already highlighted in the introduction, although these research outputs are viewed as non-traditional by the scholarly community, as Wiedemann et al rightly point out, these are actually ‘traditional tasks’ that museums carry out as part of their core functions (Wiedemann et al, 2019, p 195). Consequently, what the scholarly community views as traditional research outputs, museum professionals view as non-traditional.

This dissection and re-conceptualisation of what constituted a research output for a museum forged a new definition of what research outputs in this sector look like: exhibition texts, storyboards, animations, videos, podcasts, conservation, learning, audience engagement, to list just a few. With a new broad and creative definition and understanding of what constituted as research in a museum, it was important that this was reflected in SMG’s repository and the BL’s bespoke repository system’s functionality allowed us to highlight the myriad forms that research takes at SMG.

The population of the repository happened in two phases. The first phase consisted of locating traditional outputs, or, as we have just identified, non-traditional when considering the type of research that is conducted in museums. A sample size of work published in the last 15 years was chosen – as it was important not to duplicate archival material, e.g., older research publications dating back as far as the late 1800s when the museum was in its infancy – and journal articles, monographs and book chapters published by museum staff (past and present) were collected using Scopus. Similarly, EThOS was used to find past PhD theses.

In addition to the searches we conducted, staff were asked to self-report. A Microsoft Form was created that mirrored all the required metadata fields in the repository. This was sent to staff to complete with the metadata of their most recent publication. However, as this was a time-consuming and inefficient process – the form could only manage one set of metadata at a time – this method of collecting data was soon disregarded. The second phase involved consultation with colleagues in Research & Public History and Curatorial to understand what exhibitions SMG had run in the past and where the research outputs connected to said exhibitions lived. Members of the curatorial team highlighted exhibitions or galleries that they thought were suitable for upload. Criteria for special exhibitions included them being fully finished, i.e., not still touring to other museums, and that they did not have too many restrictions in terms of loans and partners, hence why Ancient Greeks was chosen as the pilot for this type of display.

Meeting with curators and heads of departments brought to light an issue within GLAM organisations which the Museums Association has been trying to highlight for a number of years: succession planning.[10] It quickly became very clear that without their specialist knowledge, which had been collected as a result of their years of service, a new and emerging museum professional would struggle to understand the history of the museum itself and the numerous successful projects and exhibitions that it had once completed. This further supports the need for the repository service, to document, quantify and provide a permanent and accessible home for SMG’s multitude of research outputs.

Now aware of what exhibitions had existed and when, a systematic and clear method of data collection was essential. An Excel spreadsheet was created that mimicked the metadata fields on the repository. This was circulated to those staff interested in uploading their work and proved to be a much more effective and time efficient way of collecting metadata than the originally used Microsoft Form. The efficient collection of metadata was an important hurdle to overcome because, as George has identified, ‘effective metadata management is essential for enhancing the discoverability and usability of repository content […] inadequate metadata can hinder the retrieval of relevant materials and impact the overall usefulness of the repository for researchers and library users’ (George, 2024, p 1121).

After receiving and reviewing the spreadsheet and research outputs collected, quality checking presented itself as an issue. Questions surrounding how much to edit a document emerged. To ensure consistency, each document underwent (or had already undergone) some process of ‘peer review’, i.e., approved exhibition content will have gone through several rounds of checking and verification by various SMG teams. In order for the document to qualify as a research output, it also needed to contain some element of research or data. This meant that not all project material was always included, e.g., some worksheets and pamphlets. In some cases, an editorial decision to remove aspects of the work was taken. For example, all in-text comments and tracked changes were taken out and every file was converted to a PDF before uploading. To highlight that the uploaded file was a draft form or edited version of the original document, a comment was added to its metadata: ‘Please note that the attached file is a draft copy.’ While this proved to be a time-consuming process, by standardising our method and taking the time to review every document before uploading it to the repository, this ensured that consistency was maintained with every metadata entry and upload of work.

Additionally, as Robertson and Borchert highlight, a repository is not equal to digital preservation (Robertson and Borchert, 2014, p 278). Indeed, while repositories are intended as long-term homes for research outputs, there is far more to digital preservation than merely adding work to a repository (Robertson and Borchert, 2014, p 279). Due to this, and in light of the BL cyber-attack in October 2023, part of our approach included backing up copies of work into SharePoint. While we appreciate that this is not an official form of digital preservation, it did mean that if something were to happen to the repository service, we knew exactly what documents had been uploaded.

Something that was recognised early on in the repository process was that museum repositories are different from those hosted by universities because research in museums is multifaceted. This encouraged a rethink into the types of documents that could be uploaded onto the repository. In turn, it was decided that SMG’s repository would be the forerunner in providing unprecedented access to the research practices of museum professionals. For example, by uploading draft or unedited versions of curatorial documents (gallery texts, storyboards and object labels), our audiences could appreciate the whole curatorial process.[11] Therefore, for the first time, they saw more than just the perfected final display that is on show in the museum space and understand how and why SMG’s curators make the decisions that they do. In this way, the SMG repository has expanded how repositories have been traditionally used – for example, many German museums only upload high quality and highly edited data (Wiedemann et al, 2019, p 200).

Case study one: Capturing funded research projects in the museum

Sound and Music[12] was chosen as the theme for the pilot collection as this had been the focus of SMG’s research activity for a number of years. Since the museum’s performances of Brain Eno’s Apollo music in 2009, SMG has been developing a programme of activity linking research projects and events to publications and concerts. Each of these components enabled SMG to explore a cluster of research questions relating to the ways in which people think about the technology of music, about the role of sound in museums and the kinds of sonic musical objects the museum should collect and display. It was these AHRC funded projects that formed the basis of the Sound and Music pilot collection:

- Oramics to Electronica (2011–2012)

- Artefacts Music (2013)

- Music, Noise and Silence (2015)

- Museums of the New Age: Artist in Residence (2016)

- Sound and Place: Digital Mapping and Community Listening Practice (2019)

- #SonicFriday (2020)

- Sonic Futures (2020–2021)

Unlike some of the other collections on the repository, those mentioned above were more hybrid in nature. That is to say, they were a mixture of academic and museum research and involved working with partners including the University of Nottingham, University of Leicester’s School of Media Studies and the Royal College of Music. In addition, each project was created using a range of outputs. For example, the Oramics to Electronica collection contains exhibition gallery text, object labels, object lists, case images, videos, podcasts, journal articles and a doctoral thesis.[13] Similarly, Sound and Place: Digital Mapping and Community Listening Practice houses blog posts and research reports.[14] However, while this array of outputs offered something novel, the ephemeral nature of much of this content proved challenging. This was particularly true when presented with the research outputs from the Sonic Futures and #SonicFriday projects: sound maps, Twitter posts and blogs. While the collection of digital ephemera for research is not new, the packaging of digital material onto a repository is.[15] Indeed, the collection and manipulation of digital material in order to make it ‘repository ready’, whilst also preserving its ‘digital-ness’, i.e., its interactivity, proved difficult. Subsequently, it was decided that screen recordings of each of the posts would be the best interim solution to achieving this aim.

By working with projects that produced more ephemeral outputs, this also meant that some works were not captured on the repository because of one of the following reasons:

- The file size was too large for the current storage capacity of the repository.

- The document did not include any research or data.

As it stands, the repository can only hold documents up to 1.5GB in size. When dealing with research reports, journal articles and doctoral theses, file sizes are less of an issue. However, when projects result in the production of a high definition, hour-long feature film, as was the case with Museums of the New Age: Artist in Residence, these files could not be uploaded to the repository.

In addition, early on in the repository process it was decided that, in order for a document to qualify as a research output, it also needed to contain some element of research or data. Yet, some of these more collaborative projects, such as Music, Noise and Silence, resulted in outputs such as worksheets. As these outputs in their own right did not contain any research or data, they were not included on the repository.

Case study two: Rescuing previous exhibitions for future audiences

With the pilot collection complete, work started on the collecting of past exhibition and gallery content. The exhibition Unlocking Lovelock: Scientist, Inventor, Maverick was curated by Alexandra Rose, Curator of Climate and Earth Sciences, and was on display in the Science Museum from 2013. It gave a unique insight into Lovelock’s creative mind, personality and unconventional ideas and was supported by objects including Lovelock’s laboratory notebooks, drafts of his papers, and equipment from the laboratory in his back garden. Before the advent of the repository, audiences wanting to ‘re-live’ this exhibition could only do so by searching through website pages and blogs. Indeed, Alain Dupuy et al highlight that museums do make their work accessible by uploading it online (Dupuy, 2015, p 7). Yet this was not enough. Although informative, these sites only provided a snapshot of what the original display offered. It was only by working with Alexandra that a more informed understanding of the exhibition could be obtained; gallery text, transcript for an interactive exhibit, seven videos capturing Lovelock’s responses to a series of questions about his life and career and an animation with the supporting transcript were all uploaded to this collection with their supporting metadata. Now that these documents and audio-visual materials have a permanent, freely accessible digital home, audiences wanting to ‘visit’ Lovelock’s exhibition can do so again.[16]

Similarly, through working with Ben Russell, Curator of Mechanical Engineering, object labels and exhibition text from the Dan Dare and the Birth of Hi-Tech Britain exhibition have been rescued. This exhibition was on display in the Science Museum from 2008 and, before the repository, was undiscoverable because its content only lived on internal storage drives. However, with the advent of OA and digital tools, this exhibition has now been given a new lease of life and, in turn, access to our research has broadened for the benefit of our audiences.[17]

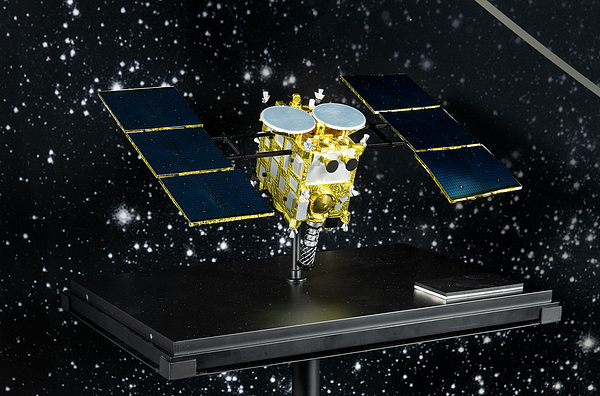

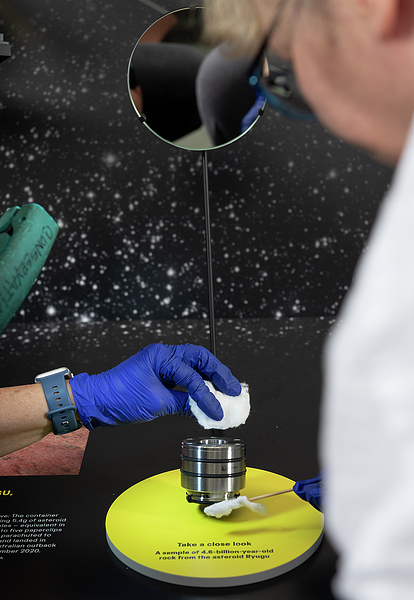

Case study three: Converting the static glass case display into an OA exhibition

Past exhibitions were not the only displays to be gifted a second life. Hayabusa2: The mission that brought an asteroid sample to Earth is currently on display in the Exploring Space Gallery at the Science Museum in the ‘showcase’ cabinet, curated by Heather Bennett, an assistant curator of technologies and engineering. This is a small space in the Museum designed to display a contemporary exhibit related to a particular theme or project (prior to this display, it had one dedicated to the 100th anniversary of the BBC, for example). Hayabusa2 displays a 4.6-billion-year-old asteroid sample that was collected by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) Hayabusa2 mission. Until recently, this display could only be enjoyed by audiences able to travel to London. Yet with the arrival of the shared repository service, what was once a small exhibition only visible to visitors peering through the glass case is now an OA museum display.[18]

In this collection, our online audiences can access the exhibition gallery text, a video, images of the static museum display and the touchscreen content available in the multimedia information kiosk beside the exhibition. In this way, the repository mimics what is shown in the glass case, providing near-complete access to what is on display – something which was not possible with the prior examples, as these were much larger exhibitions. In future, it could be standard practice to make the contents of the ‘showcase’ display case available on the repository. This work represents SMG’s first step towards becoming what Dupuy et al have called an ‘open museum’ (Dupuy et al, 2015, p 2).

Limitations and challenges

While there are numerous benefits to OA for the GLAM sector, museums still face many challenges when adopting OA principles. An initial challenge came with ensuring institutional buy-in. Too often depositing research outputs onto repositories is seen as extra workload for staff. In addition to this, the immediate benefits are not always apparent, or how the repository will directly benefit them. Not all curators have PhDs, and they do not always see what they do as research. This hurdle was acknowledged very early on in the repository process and, as a result of the pilot collection upload, a more time-efficient and easier-to-follow method of collecting metadata and outputs from staff was created. It is clear that this became the preferred method due to the number of staff who used the spreadsheet and the speed at which it was completed. Over time it is hoped that the spreadsheet method is adopted and becomes standard practice when collecting vast amounts of data from staff members in an organised fashion.

A more surprising limitation was the labour and time involved. Consistency, continuous oversight and excellent attention to detail are key skills when collecting and managing the upload of content to a repository. While this results in an expertly curated, organised and user-friendly repository it also, as John Perkins highlights, supports the notion that applying OA principles are ‘simple’ and can be ‘easily implemented’ (Perkins, 2001, p 3). OA is seen as a seamless process, quite simple and easy to do. Although a compliment for its creators, this is far from the reality. Maintaining control over the content deposited in the repository was a significant challenge. Indeed, museums have much smaller teams working in their libraries and archives than do universities, meaning that is it more challenging for museums to implement OA. To ensure the accuracy, reliability and scholarly integrity of each research output, metadata standards, policies and peer review-like mechanisms had to be enacted. While time consuming, this ensured that all the relevant research outputs could be easily accessible.

A less surprising challenge, perhaps, is the long-standing issue of copyright and image licensing. As Wiedemann et al rightly highlight, calls for OA have been weighed against the opportunities for monetary gain when using digital content (Wiedemann et al, 2019, p 195). Consequently, laws surrounding copyright and image licensing have continued to be utilised by GLAM institutions. However, as Glasemann argues, image licensing does not always prevent misuse of material. If anything, the heavy usage costs involved dissuades individuals from using the content in their work (Glasemann, 2024, p 114). Copyright and image licensing impacted SMG’s repository too. As the OA scheme is not clearly regulated or defined, the work we wanted to do was not always possible. For example, many of the curatorial documents contained images that SMG did not have the rights for and the copyright for reproducing them was not clear, therefore, an editorial decision was taken to redact such images before the document was uploaded to the repository, arguably losing some of the original’s usefulness.

A further issue when applying OA principles to museums surrounds its role in safeguarding collections. It has been argued that the ‘traditional’ museum task of interpreting objects will be challenged by the cultural shift towards open access. This is because, once content has been made freely accessible online, museums can lose direct control over use of their content by third parties (Wiedemann et al, 2019, p 193). This is problematic when the museum in question cares for culturally sensitive or politically charged objects. While this concern was less relevant to the initial upload to SMG’s repository, this does not mean that it never will be. The movement towards OA is an evolving process. Indeed, as Glasemann identifies, ‘an organisation does not automatically become an open, inclusive organisation just by applying an Open Access licensing policy’ (Glasemann, 2024, p 115). SMG will need to respond to the changing definitions of research, developments in digital infrastructure, and the challenges that OA brings as they continue to situate themselves within the domestic and international GLAM landscape.

Ensuing the long-term sustainability and preservation of the repository and its content is another issue. As things stand, digital preservation is not available on the BL’s repository service. Due to this, a multi-team approach is needed when applying OA principles to museums. For the repository to survive, sustainable funding models are needed and more institutional support for repository maintenance and preservation efforts is required. Navigating these challenges requires strategic planning, collaboration with stakeholders, and ongoing investment in technological infrastructure and human resources (George, 2024, p 1121). However, time given to these factors will safeguard the integrity and accessibility of the repository and its research outputs.

Growing the repository 'audience'

Similar to museum content, audiences for the repository need to be considered. However, the repository does not have the same user-friendly interface as more curated online spaces, such as Google Arts and Culture or museum websites. This understanding of the system informed our approach, and we made sure that SMG’s repository was clear and accessible and that the user journey was easy to navigate, within the constraints of the interface. Now home to research outputs of staff within the Group, the repository has the potential to be an internal resource at SMG and also for museum practitioners more generally. The works can be used as a teaching aid for students, educators and aspiring museum practitioners and as academic resources for researchers and non-professional researchers. SMG can also show the material on the repository to the academic disciplines of museum studies, science and technology (STS) and science communication. Simultaneously, the repository can be included on the UCL module ‘Curating Science and Technology’ that is currently taught by SMG. Furthermore, all current research grants active at SMG can upload their outputs to the repository, while it can also be written into any future bids.

Following the population of the repository, we strategized on how best to promote the repository internally and externally to ensure that audiences became aware of its existence. We decided to create a short video, easily shareable on social media, which explained what the repository is, what it contains, and how it links into the wider SMG digital landscape (see below).

Looking ahead, the repository can help SMG achieve its aim of being ‘open for all’. In their latest strategy (2022–25), the Group stated that it wishes to ‘improve the communication of existing inclusive and accessible features both online and onsite and develop new resources, such as Sensory Friendly Maps and pre-visit guides to help audiences feel comfortable and at home in our sites’.[19] Once developed, the repository can provide a home for these new and more inclusive resources.

The repository complements the OA work that SMG has already been doing and provides a means of expansion. SMG was one of the first museums to have an OA Museum Studies journal. Now with the repository, the journal has a more secure second home and, in future, it may be possible to use the repository to create an overlay journal or upload pre-prints in line with the changes happening across scholarly publishing. The repository also acts as a key mechanism for opening up the collections of the museum. Objects with an entry on the Collection Online[20] website – the digital resource that provides access to objects beyond the museum floor – can be linked to the related research outputs on the repository. The inclusion of this metadata field allowed us to create meaningful interactions with different departments across SMG as content on the repository can signpost users to the Museum’s other websites and digital resources, and vice versa. The result is that SMG’s research is more accessible, discoverable and connected and the repository can grow in coherence with SMG’s other digital platforms.

For the repository to continue to grow, further work will need to be done to think about users, as well as how the repository can reflect the research of more departments in the Group, e.g., Learning and Conservation. Surveys and data or usage from Google Analytics and IRUS need to be collected too. This will allow SMG to monitor traffic, evaluate its marketing and understand its repository users better.

Conclusion

It has been the aim of this article to illustrate that the research that museums undertake is not directly equivalent to academic research, and thus OA principles for scholarly publishing do not neatly map onto museum (and GLAM) research. However, what the introduction of OA stipulations from funders has offered is a chance for IROs to reconsider the modes of research they undertake and how to make this more accessible to their audiences, moving beyond an understanding of open GLAM that only relates to collection images and metadata. By extension, this allows the GLAM sector more broadly – irrespective of whether they receive funding with OA stipulations attached – to understand more parts of the work they do as valuable research outputs that can and should be shared beyond the confines of galleries and exhibitions. This, we contend, can create a more transparent understanding of how content is created, offering examples of museological practice that might otherwise seem obscure – this can have enormous benefit for working GLAM practitioners and the practitioners of the future (such as museum studies and science communication students). By sharing material like exhibition plans, story matrixes and other planning documentation, a museum’s repository, beyond the archive, can act as a memory of museological practice, something notoriously difficult to excavate without speaking to practitioners themselves.

Using SMG as an example, we have offered one model for how museum research outputs can be conceptualised and shared via the digital platform of a repository. While repositories have grown out of the academic realm, we have showed how research outputs can take on a new logic through the bespoke repository service created by the BL and funded by the AHRC, which has metadata capacities for wide-ranging outputs – from journal articles to exhibition items. And, as universities expand the definition of academic outputs to include those more akin to the research conducted in museums, our findings can be fed back into the academic realm. We have shared our methodologies and three case studies to offer insight into our approach to building the SMG repository. We do not claim this to be the optimum or the only method for approaching the dissemination of research outputs for museums – this is recently completed work, and we are yet to fully understand how the content will be received and used. We have discussed, therefore, how the repository could grow in line with goals to reach wider audiences through digital engagement.

However, as with several areas of museum work in the contemporary moment, time and funding is limited for this kind of work, which means that the first iteration of the repository has come to a close with further plans dependent on more funding coming into the Museum. A wider challenge for the OA movement in the museum sector is securing and maintaining the necessary funds to employ staff to run the digital systems that are being developed. While the digital is often seen as a cost-effective alternative to the physical realm, this is not always the case, with the digital sphere requiring maintenance and upgrades in the same way that a gallery floor does.