New mobile experiences of vision and modern subjectivities in Late Victorian Britain

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191204

Abstract

This article looks at the relationship between two very popular middle-class activities in Late Victorian Britain, photographing and cycling, and explores the influence that the new technology of physical mobility had on visual experiences and related photographic practices. It focuses, in particular, on the significance that new practices of mobility and visuality had for a growing body of amateur photographers as they negotiated these experiences as a temporality of late nineteenth century modernity. Drawing on the everyday historical experiences of cycle and photography users as these were articulated at the time, the article offers new insight into the role that such body-machine interactions had on the development of what was, effectively, a modern, moving, gaze. My argument is that the sense of control over the new ways of moving and seeing enabled by cycling contributed to shape a new visual self and that, in turn, this fuelled the desire for a new visual language and means of representation that could challenge dominant photographic practices, in a manner that foresees the emergence of snapshot photography.

Keywords

camera technology, cycle technology, cycling, instantaneous photography, mobility, pictorialism, snapshot photography, visual modernity

Introduction

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/In February 1886, in a letter printed in the official publication of the Cyclists’ Touring Club (CTC), Edward R Brennan wrote:

Sir, – In the C.T.C. Gazette for December, a suggestion is made that, as a winter evening’s amusement, numbers might utilise the magic lantern. I have long since done so. I lectured three times last winter on the ‘Beauties of Irish Scenery,’ and, with a good magic lantern, lime-light, and a 20ft. sheet, tried to please the eye, and at the same time convey to my audience the impression made on me by seeing the world from a bicycle. I am collecting photos of places visited by me in England, and hope to take up that subject later on.

Brennan was one of the consuls of the CTC,[1] a national organisation founded in 1878 with the aim of supporting a growing body of leisure cyclists.[2] Consuls such as himself had the task of approving hotels and inns in the area under their care – in his case the county of Waterford, in the southeast of Ireland[3] – which were then listed in members’ guides and handbooks. Like many other cyclists at this time Brennan was also a photographer,[4] and as such his familiarity with using the lantern was not unusual.[5] While both cyclists and photographers spent the summer months outdoors, during the winter months less available light and poor weather conditions largely limited both practices, making room for indoors social activities – including lantern entertainments.[6] The photography and cycling press of the period confirm that it was common for members of camera and cycling clubs to lecture using lantern slides, sometimes just within their own club or to a paying audience.[7] Brennan seems to have been particularly successful at this, as he commented later on in his letter that ‘my three lectures last winter yielded £12, £16, and £18, and this in small towns’ (1886, p 65).[8] While, to the best of my knowledge, whether his slides have survived is unknown, the title of this lecture, ‘Beauties of Irish Scenery’, and of the one that he was planning, ‘places visited by me in England’, indicate that the subject matter broadly coincided with what other tourists were taking at this time: sites of historical and heritage significance, or of particularly natural beauty (Dominici, 2018a; Taylor, 1994).

One noteworthy passage in Brennan’s letter, however, suggests that he thought that his photographs were somehow different from those taken by tourist photographers who did not cycle. Or, rather, his comment that in his lecture he sought to ‘convey to my audience the impression made on me by seeing the world from a bicycle’ points towards the recognition that the experience of cycling was somehow transforming how he looked at his environment and, consequently, how he wished to represent this experience. Brennan was not alone in drawing a connection between new experiences of mobility and visuality; many other photographers were similarly commenting on the influence that cycling was having on their visual experiences (Dominici, 2018b). Since the late 1870s a growing body of upper- and middle-class amateur photographers, the only group who could realistically afford both technologies, had enthusiastically embraced cycling as it facilitated individual mass-mobility and thus a broad photographic practice (Dominici, 2018b; Edwards, 2012, pp 67–68). In the process, these self-propelled machines shaped their visual experiences by enabling a new relationship with their environment: as we will see, it was common for cyclists to describe what they saw while cycling in terms of ‘impressions’, ‘fleeting images’ or ‘glimpses’ felt as entirely under one’s control.

This new independence in mobility and visuality influenced what cyclists thought of photography and what they came to expect of it. Indeed, Brennan’s comment that he tried to ‘convey…the impression made on me by seeing the world from a bicycle’ suggests that he did not consider his photographs to be sufficient per se in recreating such an impression, something that, we can assume, he attempted to address with the lantern by sequencing the images in a particular way and by adding his commentary. As was the case with many other cyclists, the visual experiences that they wrote about when they came back from their tours do not seem to match the photographs they took.[9] In the interaction with technologies, a new way of visualising being in the world emerged.

In this article I explore the relationship between such new body-machine synergies and ensuing visual practices. Specifically, I look at the influence that cycling was felt to have on one’s sense of self and place and, in related fashion, at how the interaction between the movement of cycling and the static nature of the photograph fed into a growing interest in the representation of an individual experience of motion. This, I argue, implicitly challenged existing visual practices, laying the ground for the emergence of a new, informal, visual language as the expression of a new modern subject. Importantly, then, the aim of this article is not that of examining the visual language per se that the new mobility enabled, nor that of establishing a link between users’ experiences and products. Rather, the article seeks to understand how the engagement with camera and cycle produced modern subjectivities that wished to use the camera apparatus in new ways. In other words, it explores the cultural formation of these amateur photographers and their desire for a new way of expressing visually one’s sense of being in the world as a product of a technology-enhanced experience of modernity, something that precedes actual photographs themselves. This was akin to that ‘desire to photograph’ that, as Geoffrey Batchen argues, ‘only appears as a regular discourse at a particular time and place’ (1997, p 183). The demand for new technological developments that followed was, in this sense, a materialisation of such desire. For this reason, in what follows I look at the experience of visual modernity from the ground or, as Latour puts it, I ‘”follow the actors themselves”…in order to learn from them what the collective existence has become in their hands’ (2005, p 12). By reconstructing the everyday experiences of camera and cycle users, the article will contribute to our understanding of how photographers came to see and act the way they did.

I start with a brief outline of the development of the practice of combining photography and cycle for leisure purposes from the end of the 1870s. I then present a framework for the analysis of photographers’ visual practices that considers the experience and temporality of late nineteenth century modernity in relation to the new physical mobility enabled by cycling. Here I focus, in particular, on the significance that the engagement with self-propelled vehicles had on people’s way of seeing and, consequently, understanding the world. Finally, I use this perspective to examine the confluence of photographing and cycling as this was articulated at the time, and photographers’ desire to recreate what they saw while cycling in a way felt as representative of their new mobile visual experiences. As this will hopefully show, new experiences of moving and seeing shaped a new visual self and this, in turn, fuelled the desire for a new visual language and means of representation long before the more informal aesthetic generally associated with mass photography, and which I argue was pre-empted by cyclists’ photographic desires, emerged.

Setting the scene: photographing and cycling in Late Victorian Britain

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191204/002While the earliest attempts at carrying a camera on self-propelled wheels date back to the late-1860s,[10] this activity acquired a broader appeal amongst the middle classes only in the mid-1870s, when cycle technology developed a fundamental modern feature: speed (Herlihy, 2004). With vehicles that could now go faster and further afield, the bicycle became part of modern life in a way that transcended its merely functional use as means of transport. First with cycle racing, and by the close of the 1870s with cycle touring too, the bicycle developed a new distinctive cultural significance. A key reason for this, as we will see, was that it offered new ways of adapting the physical self to the modern world by extending the capabilities of the human body, and thus its perception of and engagement with space. By the mid-1870s the high-wheeler (also known as the ‘ordinary’ or penny-farthing) had become the standard bicycle in Britain regardless of the fact that it was dangerous to ride. The main reason for its popularity was that it was fast, much faster than its predecessor, the velocipede. The high-wheeler was particularly favoured by athletes, and cycle racing quickly became a popular public spectacle.

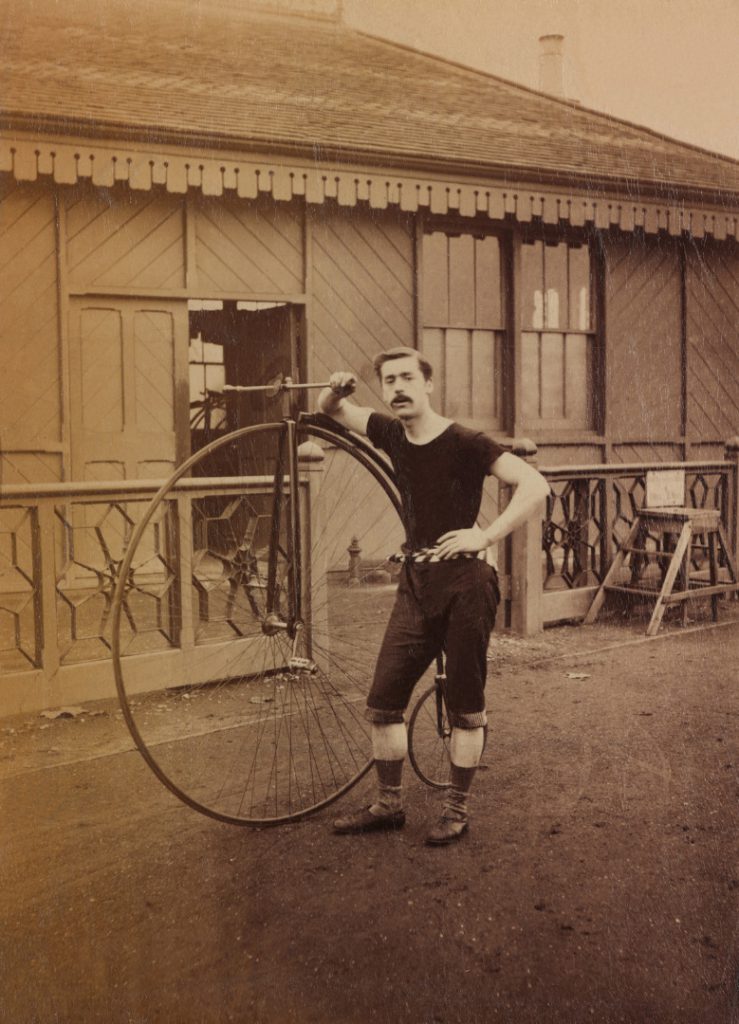

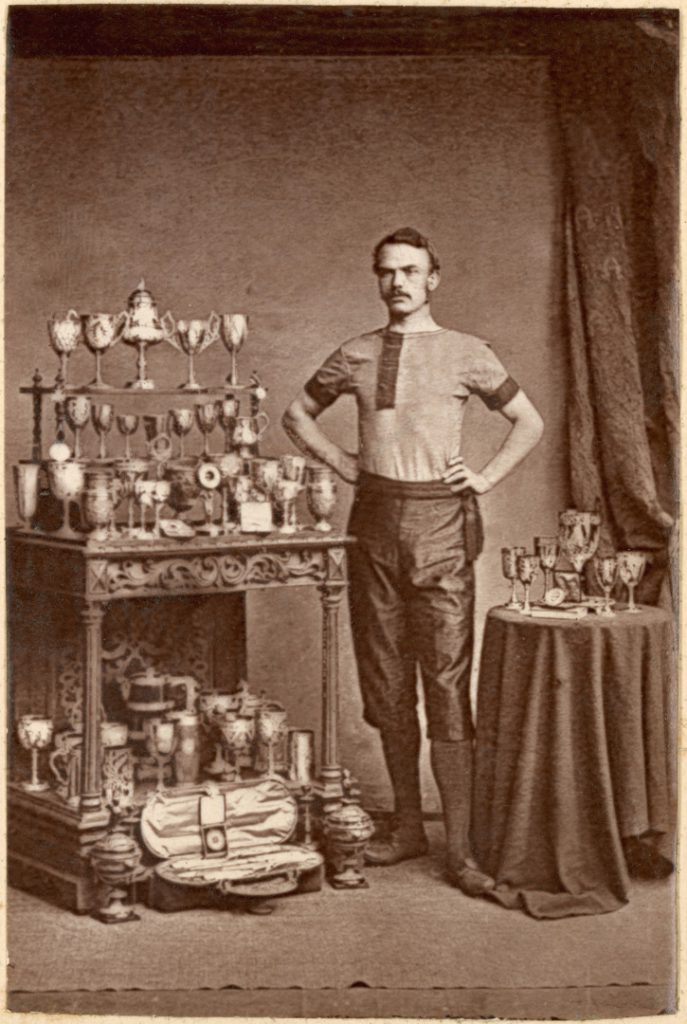

Figures 1 and 2 show two cycle races from the early 1880s, giving a sense of the crowd that gathered to watch these events.[11] These competitions put the human body on show but also on trial, showing how the body could be pushed, and thus celebrating its achievements. This was a time when body-machine interactions were central in the public debate, with opinions differing on the nature of technological advancements. As Foster for example recognises, ‘the human body and the industrial machine were still seen as alien to one another…the machine could only be a “magnificent” extension of the body or a “troubled” constriction of it’ (2004, p 109): in the case of cycling, it was generally considered to be the former. What is celebrated for instance in photographs such as Figures 3 and 4 is a specifically modern aesthetic of the athlete’s body enhanced and put on display thanks to its engagement with the new technology.

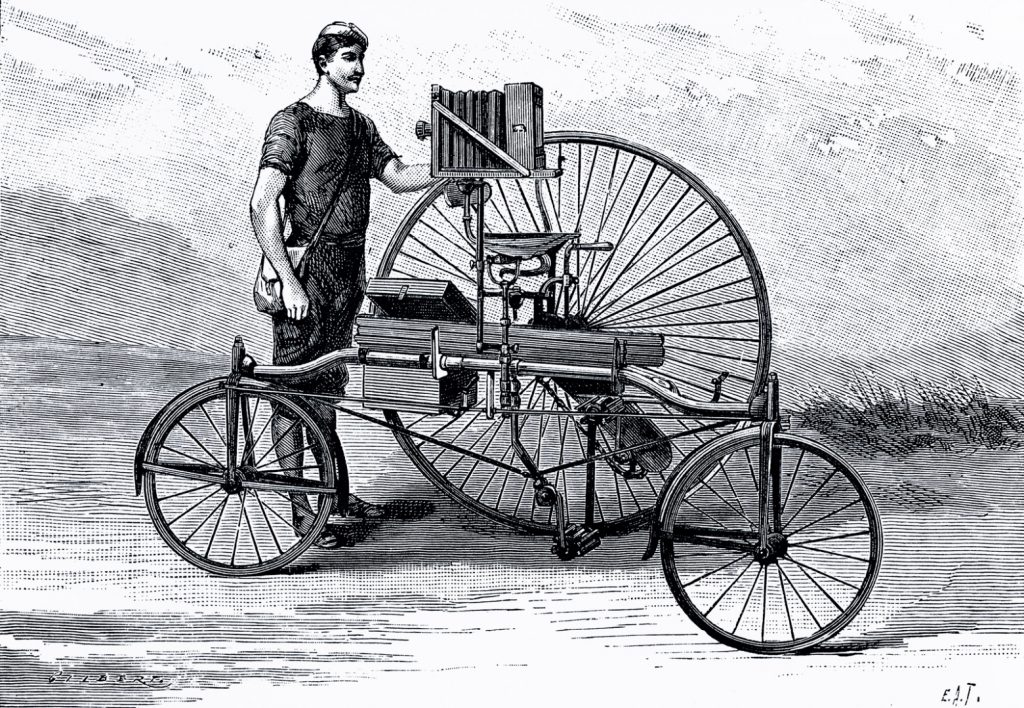

Cycling also allowed people to transform their physical self in another, more widely accessible, context: that of touring. The success of cycle racing energised the British cycle trade, which by the end of the 1870s was flourishing, and it also fostered the demand for cycles that the wider public could use in their leisure time. The high-wheeler was dangerous to ride, so manufacturers started developing three- and four-wheeled machines (tricycles and quadricycles) easier and safer to use and that allowed for the carrying of luggage too. Figure 5, for example, shows a popular model amongst photographers, the Rotary Tricycle produced by the Coventry Machinists’ Company, with a bellow camera mounted on it.[12] Figure 6 shows two other tricycles next to a photographer and the glass plate cameras that, we can assume, would have been carried on these tricycles.

Simultaneously, the appeal of independent travel was also fostered and supported by organisations such as the CTC, which proved extremely successful: from eighty members in 1878, the membership had reached almost 11,000 in 1883, over 20,000 in 1885, and peaked at more than 60,000 by the close of the century. Together with the gazette, handbooks (which, starting in 1887, also detailed facilities providing a darkroom)[13] and guides produced by the CTC, cyclists had at their disposal a number of other tools that encouraged them to travel ‘far from the beaten track’ (George, 1885, p 344): OS maps, travel guides, cyclometers, lamps, not to mention the sharing of personal experiences and recommendations that took place within the pages of the photography and cycling press and, as Brennan’s letter indicates, within photography and cycling clubs. Indeed, at this time many cycling clubs opened a photographic section, as camera clubs did a cycling one.[14] Additionally, at the end of the 1870s dry plates started to be mass-produced (Pritchard, 2010). It was now no longer necessary to attend to the glass-plates immediately before and after exposure, as was the case with the wet collodion process. This made the taking of photographs outdoors much more practical. As a result of these changes, cycle and camera makers began promoting their products to photographers and cyclists respectively – for example, in 1879 the magazine Cycling reviewed the Scenograph camera (1879a), while the Coventry Machinists’ Company advertised on the front cover of the first issue of the AP in 1884. These advertisements, together with editorials, letters and articles praising the combination of camera and cycle appeared with increasing frequency in both the photography and cycling press. By the close of the century contemporary commentators agreed, as the AP for example declared, that ‘the cycle and camera are indissolubly wedded to one another’ (1899, p 1).

As I argue in the following section, by embracing the new technology of physical mobility amateur photographers found themselves in the position to negotiate – or, at least, that was the promise – the experience and temporality of late nineteenth-century modernity. This led to the emergence of a desire to use photography in consonance with their new spatio-temporal experiences.

Mobility and visual experiences of modernity

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191204/003In one of the most famous and influential accounts of modernity, Marshall Berman writes that the ‘highly developed, differentiated and dynamic landscape’ within which the experience of modernity took place was one:

of steam engines, automatic factories, railroads, vast new industrial zones; of teeming cities that have grown overnight, often with dreadful human consequences; of daily newspapers, telegraphs, telephones and other mass media, communicating on an ever wider scale; of increasingly strong national states and multinational aggregations of capital; of mass social movements fighting these modernizations from above with their own modes of modernization from below; of an ever expanding world market embracing all, capable of the most spectacular growth, capable of appalling waste and devastation, capable of everything except solidity and stability.

This evocative description articulates some of the key features which are understood to characterise nineteenth-century modernity: an ever-changing and fast-paced urban environment, the emergence of a developed capitalist society, acceleration of scientific and technological innovations, and an increase in visual stimuli. This last point, in particular, has often been taken to signal a rupture with the amount and type of information previously available, according a new and specific importance to the visual in the understanding of the world. For example, Jonathan Crary writes that this period saw a ‘new valuation of visual experience’ that was ‘given an unprecedented mobility and exchangeability’ (1990, p 14). ‘The modern era’, Martin Jay notes, ‘has been dominated by the sense of sight in a way that set it apart from its premodern predecessors and possibly its postmodern successor’ (1988, p 3; see also Mitchell, 2000). Many well-known nineteenth- and early twentieth-century thinkers and artists similarly noted the kaleidoscopic, fractured and alienating (visual) experiences that such spatio-temporal dynamics had resulted in. Famously, Charles Baudelaire described the experience of modernity as that of ‘the ephemeral, the fugitive, the contingent’ (1863, 1995, p 13),[15] while Walter Benjamin, drawing on Baudelaire, wrote of it as ‘a series of shocks and collisions’ that diminished human experiences because they could not be assimilated (1939, 1997, p 132).[16] In both instances, visual modernity is presented as an urban phenomenon born out of new practices of mobility, and ensuing viewing experiences interpreted as fundamentally affected by the accelerated character of modern life.

These readings suggest that it was not just that visual stimuli were multiple and kaleidoscopic in character, but also that people appeared not to be in control of them. At first, these descriptions may seem reminiscent of cyclists’ visual accounts, which likewise recalled the experience of encountering a fast-changing sequence of visual stimuli: indeed, cyclists commonly described their visual impressions in terms of ‘fleeting glimpses’ (1884c, p 3), of catching ‘a glimpse of a sweetly pretty scene’ (1884b, p 165) or ‘many a glimpse of tree and heather’ (Selby, 1897, p 380). Yet, as Berman notes, if on the one hand modernity suppressed the individual by creating standardisation and uniformity, including of visual experiences, on the other it also pushed the individual (particularly the middle-class subject who was gaining self-determination) to search for ways to escape from modern rationalisation itself. This was a balance between ‘a will to change – to transform both themselves and their world – and a terror of disorientation and disintegration, of life falling apart’ (Berman, 1983, p 13) – what, in Matei Calinescu’s words, we could describe as the ‘battle for the modern’ fought by the middle classes (1987, pp 41–42), of which bicycle-owning photographers were certainly a part.

It is within this context, I argue, that we need therefore to consider the impact that the practice of combining photography and cycling had on visual experiences and related photographic practices. From this perspective, cycling promised modern subjects one way ‘to transform both themselves and their world’ (Berman, 1983, p 13) by fostering a new way to be in the world that, in turn, influenced how people saw the world and wished to represent such experience.[16] While the engagement with a modern machine provided social recognition and the sense of participating in a modern project, the perception of independence that came with controlling the vehicle simultaneously allowed for the preservation of a bourgeois and individualist experience of travel (Jamieson, 2002; Oosterhuis, 2016). This shaped how cyclists related to the landscape they rode through. As Tilley notes, ‘[s]pace is socially produced…meaningfully constituted in relation to human agency and activity’ (1984, p 10). From this perspective, we can say that cyclists’ understanding of the world was shaped by how the technology-enhanced movement made them act and feel, and that this, in turn, shaped their visual perceptions (see also DeCertau, 1984). Cycling, then, was not simply a more efficient way to reach a particular location: early bicycles changed the relationship between the physical self and its environment, as seen and traversed, by allowing the former to feel in control over the latter. This was an active engagement with the spatio-temporal dynamics of modernity that enabled a sense of domestication of these experiences, in doing so allowing photographers to enhance (or so was the promise) one’s body and senses. Indeed, what is striking in cyclists’ accounts is a sense of freedom in mobility as well as visuality that the combined use of cycle and camera seemed to promise, and which differed from the collective (visual) experiences provided by other means of transport such as the railway. For example, Harry Hewitt Griffin, the editor of Bicycling News, wrote in the Amateur Photographer to promote, as its title explained, ‘Cycling with the Camera’, that thanks to cycling: ‘Railway time-tables become a sealed book…when an “artistic journey” is contemplated, and one becomes gloriously independent of return tickets and the limited field of operation which is generally entailed by a train journey’ (1885, p 201). Ernest R Shipton, the Secretary of the CTC and editor of its gazette (and thus the author of the incitement to which Brennan, as noted in my introduction, had responded), as well as a photographer himself, wrote in a paper delivered to the Camera Club in London in 1887 that: ‘Upon a cycle he [a photographer] is his own master; his time is at his disposal; and if, in stopping by the way, he fails to reach his intended destination, what matters it? It but means another enjoyable day in store’ (1887a, p 119; 1887b, p 125).[18] If you cycle, G Sullivan similarly commented in 1896, ‘there is a never-changing prospect before you; your journey will abound with endless varying incidents and delights’. Yet, the author continued, ‘seen from the window of a railway carriage, this self-same country will seem tame to the last degree’ (1896, p 449). In this sense, cyclists’ accounts of their visual experiences can be understood as a particular expression of Berman’s more general ‘will to change’ (1983, p 13): that is, not simply as the indication of an ever-changing and alienating visual environment, but as an attempt to express themselves in a way that transcended modern rationalisation itself. The engagement with the technology, then, allowed people to develop a new individual sense of self whose constitution stood in opposition to those mechanisms of regulation and conformity that were shaping everyday life. This influenced cyclists’ perception of how photography should be used to represent these experiences: this was a modern subjectivity that strove for a new cultural expression.

There is a wealth of literature that discusses how modern technologies fundamentally altered perceptions of time and space, fostering new ways of articulating such experiences that questioned established social, cultural and aesthetic orders.[19] Stephen Kern, for example, writes that:

The plurality of spaces, the philosophy of perspectivism, the affirmation of positive negative space, the restructuring of forms, and the contraction of social distance assaulted a variety of hierarchical orderings. While the plurality of lived spaces envisioned by the geometers, physicists, and biologists and those created by the painters and novelists did not always aim directly at the social structure of the aristocracy, they energized a general cultural challenge to all outmoded hierarchies.

I argue that this ‘cultural challenge’, which Kern examines in relation to literary and artistic sources, also took place amongst middle class amateur photographers who cycled. In other words, their embodied experience of space was part of a broader shift towards a technologically-enhanced participation in the world that sanctioned personal and individual perspectives.[20] While their actions were not driven by that ‘conscious commitment to modernity’ (Calinescu, 1987, p 86) that describes the modernists at the centre of Kern’s account, we can certainly think of them as popular modernists in the sense that their practices implicitly questioned established photographic canons. As the reconstruction of their everyday experiences indicates, the combined use of camera and cycle had produced a modern subjectivity that, perhaps at an unconscious level, felt the urge to use photography differently: in other words, the interaction with these technologies challenged hegemonic canons by forming modern subjects that projected visual and technological desires into the future. The important point, then, is that for those photographers who had embraced new forms of personal mobility, individual vision had started to mean something different. Indeed, we can see the emergence itself of a new term such as ‘cyclo-photographer’, which was coined at this time to describe the combined use of cycle and camera (Dominici, 2018b), as gesturing towards the self-awareness that a new visual self also necessitated new means and practices of representation. To put it another way, the consciousness of a new relationship with self and place enabled by cycling was instrumental in shaping, in turn, a desire for new ways to represent such new (visual) experience. This means that cyclo-photographers wished to represent their world long before they had adequate tools to do so: it was their practices, rather than their photographs, that anticipated the emergence of new aesthetic modes.

Significantly, in fact, the photographs that cyclists took do not present any discernible signs of such a transformation in visual practices: they just do not seem any different to our eyes from what other tourists were taking at this time. There are two main reasons for this: the first is linked to the tight connection between established aesthetics and class, particularly the dominant photographic aesthetic of their time, pictorialism.[21] Amateur photographers who sought to take part in the exhibitions, prizes and lantern shows taking place in the winter months, for example, were encouraged to imitate paintings (i.e. romantic landscapes and rural idylls) in order to demonstrate their own value as artists and, consequently, members of a respectable class. As Edwards argues, these ‘artistic aspirations of amateur photographers were…closely related to class, namely in the difference between the educated and aesthetically attuned gentleman and the artisanal mechanical operator’ (2012, p 85). The relationship between pictorialism and amateur practice found a fertile terrain in the context of touring (Taylor, 1994), as this attitude to representation aligned itself with the long-standing debate between the self-appointed and sensitive traveller, and the ‘vulgar’ tourist (Buzard, 1993; Lofgren, 1999). Conforming to this aesthetic – or, in contemporary terminology, to acquire the proper cultural capital – was then crucial for a class that was seeking self-determination. As a number of scholars have indeed demonstrated, culture came to be considered ‘a significant – if not indispensable – part of what it meant to be “middle class”’ in this period (Gunn, 2005, p 24; see also Wolff and Seed, 1988; Young, 2003). This was part of a wider project, championed by both the photographic press and photographic societies, that sought societal appreciation of photography as an art form, in doing so privileging a collectively recognised way of seeing over idiosyncratic vision – something that, as we will see, was questioned by the technologically empowered individual in modern society.

The other reason, addressed below, is that available cameras somehow restricted the engagement with new visual stimuli that photographers sought. It is thus in their written accounts that we need to look for evidence of how the established visual order was falling short of the desires of a modern, moving, gaze and, consequently, of how the desire for a new visual language had begun to emerge.

Representing a modern, moving, gaze

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191204/004In December 1885 the AP published an article titled ‘The Camera on Wheels (Highly Commended): From London to the Isle of Wight’, penned by H H Dore. The text offered an account of a five-week cycling tour that the author and his brother had made the previous summer. In the article, which is representative of many similar accounts published in the photography and cycling press in this period, Dore sketched the route followed, described some of the photographs taken during the trip, advised on the tricycle and camera used, and enthusiastically encouraged the readers of the AP to touring with a ‘camera on wheels’, as the article was appropriately titled. Dore thus began:

Of all modes and manners of touring, that of a tricycle far surpasses any other means of locomotion, as at once being the fastest (of course, barring steam) as well as the most pleasant. Who can appreciate better than a cyclist the lovely stillness of a summer’s night, with the landscape bathed in Luna’s uncertain light? What can be more exhilarating and soul-stirring than to glide through such a scene on wheels? Would that the sensitive plate were ‘quick’ enough to fix so fleeting an image as this!

While the opening sentence highlights the benefits associated with this new way of moving – chiefly, independence, as a cyclist was completely in charge of where and when to go – the two questions that follow and the concluding statement illustrate instead how such movement was influencing riders’ visual experiences. The first rhetorical question describes a lack of movement: Dore writes of the lovely stillness of the landscape, a motionless and quiet scene that is unaffected by technology. With the second rhetorical question, however, the text accelerates: Dore explains how the movement enabled by the tricycle allowed him to disrupt and cut through this stillness. He writes of ‘gliding’ through such a scene, of the exhilaration and intense emotions that this arouses. This sense of distance shrinking and time accelerating not only disrupted the landscape, which is no longer still, but also transformed Dore’s visual impression of this landscape: it is key, in the last sentence, to note how he describes what he saw while riding as a ‘fleeting image’ – a trope that, as we have seen, recurs in cyclists’ recollections of their visual experiences.

Yet, as Dore’s remark indicates, the existing technology was not considered adequate to engage with these new visual experiences. Let us consider, for example, the only photograph from his tour that was published with the article (Figure 7), and its caption – ‘Rustic Lane, Puckaster Cove’ – and description – ‘a bit in a lane leading to Puckaster Cove, very narrow and generally very dirty, and a great deal too rough for a tricycle even to penetrate’ (1885, p 588). There is no sense here of that technology enhanced transformation of the experience of time and space that, by contrast, Dore’s account conveys – in this case, also because Dore seems to have had difficulties riding on the path. Yet, while the cycle was considered to enhance the body of photographers for the reasons detailed above, existing camera technology was seen to do the opposite, that is, to slow down and to impair a photographer – hence the difference in pace, so to speak, between Dore’s description of his visual experiences and the accompanying photograph. This was, firstly, because the process itself of taking a photograph was indeed rather laborious. A typical description is offered by Caleb C Smith, the photographic editor of Tricycling Journal who ran the weekly column ‘Photography on Wheels’:

Now having selected the ‘bit’ upon which we are to make our first attempt, we will ‘rig up’ our camera in position, remove the cap off the lens and place our head under the focussing cloth. Having taken out the stop, if it be a detachable one, or if rotary turn it round until the largest one is in use. Now as a great flood of light will thus be admitted, we shall be able to see distinctly to focus, now by opening and closing the camera (either by the focussing screw or by simply opening and shutting in the case of our camera, not having a screw fitted.) The student will soon find when the image is sharpest. […]

When the student believes that he has got his image sharp, place the smallest stop in the lens. We recommend the use of the smallest stop so that the student may give a longer exposure, and thus not experience so much difficulty in developing his first plate. Now the cap must be replaced and the student proceed to prepare his dark slide for use.

As I have discussed elsewhere (Dominici, 2018b), there is ample evidence that cyclo-photographers found the slow pace that this process required at odds with their newfound visual and mobile independence. Secondly, as Dore’s remark – ‘Would that the sensitive plate were “quick” enough to fix so fleeting an image as this!’ – suggests, the existing camera technology prevented photographers from engaging with their new visual experiences because of an issue with the sensitivity of commercially available glass plates, which were only just becoming fast enough to capture moving subjects.[22] This demand for instantaneous photography was widely shared by photographers who cycled. In 1887, for example, Henry Sturmey, the editor of Cyclist and a photographer himself, noted that ‘an exposure sufficiently quick to secure good pictures of objects in motion…is a fascinating pursuit which appeals, perhaps, more directly to cyclists than to any other class’ (1887, p 124) – an observation that implicitly links cyclists’ experience of time and space with their photographic desires.

Kim Timby has recently argued that such new photographic possibilities ‘may…have helped give form to the desire for a cinematic image: with the new dry plates, it was possible to photograph the modern, moving, fleeting world, but these images looked frustratingly inert’ (2018, p 184). This was part of a quest for a ‘successful imitation of the experience of vision’ (Timby, 2018, p 181) that informed wider discussions about photographic realism and truth (Belknap, 2016). My argument, however, is that we should understand this eagerness to engage with ‘fleeting images’ not simply as a desire to capture and thus reproduce motion but, most importantly, as a way to negotiate the motionless nature of the photograph with the accelerated and highly individualistic vision of the cyclist, what we can describe as a modern, moving, gaze. As Elizabeth Edwards notes in relation to the photographic survey movement, active between 1885 and 1918 with the purpose of recording the English past, ‘photographs represented moments of stillness in the movement of the photographer through the landscape, not only because the nature of the photograph itself, but because the moment of observation on which the surveys were premised was made from a stationary position’ (2012, pp 72–73, original emphasis). Instantaneous photography, which ‘carried an assumption of directness and spontaneity of observation…[and] stood for a direct, unmediated translation of vision itself’, met the aims of the survey because it was seen to enable the ‘immediacy of the historical’ (Edwards, 2012, pp 71, 72). For photographers who cycled, however, the ‘moment of observation’ that they wished to recreate took place from a moving position, while the ‘directness and spontaneity’ of vision of the instantaneous photograph appealed to this new way of seeing because of the embodied sense of technology that it provided. The product of a hand-held camera, the instantaneous photograph seemingly extended a photographer’s vision across the modern world in the same way in which the cycle was felt to extend the capabilities of one’s body. This allowed cyclists to capture, and thus understand, what the moving gaze could only see as ‘glimpses’, ‘impressions’, or ‘fleeting images’, simultaneously inspiring photographers to think of their own vision as kaleidoscopic and rapidly changing. It was the desire to articulate visually this new sense of one’s own presence in the experience of seeing, I argue, that also influenced the emergence of a new, informal, visual language.

It is striking, in this respect, to notice how the desire to represent this new sense of independence in visuality is reminiscent of (or anticipates) the cinematic montage of the early twentieth century. As is well known, cinema has often been discussed as the technology that in primis allowed for an articulation, and thus understanding, of modernity, ‘designed to capture and reveal, far beyond the shape of things, the rhythm by which the world moved and changed… [W]ithout cinema, modernity is unthinkable’ (Pomerance, 2006, p 12). Benjamin’s influential claim that ‘technology has subjected the human sensorium to a complex kind of training’, and that this ‘urgent need for stimuli was met by the film’ (1939, 1997, p 132), for instance, highlighted both the numbing effects that visual modernity was seen to have on the body, and cinema’s capacity to protect the human sensorium by manipulating such visual stimuli so that they could be taken in. It is along similar lines, I argue, that we should also consider cyclists’ interest in instantaneous photography, and the transformational influence that the confluence of new ways of moving and seeing had on photographic practices. Specifically, we can think of cyclists’ desire to find new ways to engage with the ‘fleeting image’ as a pre-cinematic attempt at expressing the experience and temporality of modernity from the perspective of the individual: in other words, an attempt at adding temporality and one’s own sense of self and place to the motionless and aesthetically rigid photograph. Brennan’s comment, at the beginning of this article, that he tried to ‘convey…the impression made on me by seeing the world from a bicycle’ in using the lantern can thus be understood as an effort to recreate both its subjective experience of the world and the new pace at which he felt this was now taking place. That is to say, the experience of visuality fostered by cycling foresaw the perceived sense of immediacy of the snapshot in the sense that it urged a new visual language in consonance with the sense of autonomy, individual agency and informality that had come to shape these photographers’ new experience of being in the world. This, in turn, challenged the photographic aesthetic fashionable at the time, pictorialism, in that the latter’s association with the historical record (Edwards, 2012) and its rigid rules of self-expression (Robinson, 1889) clashed with cyclists’ desires for a more spontaneous and embodied form of visual expression representative of the visual experiences of a modern subject.

Conclusion

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/191204/005In 1905, advising in the column ‘Cycle and Camera’ on the best lens to use for ‘cycle-touring purposes’, ‘A. Wheelman’ (a pseudonym) declared that ‘[i]n this hurrisome twentieth century, a time exposure is as rare as the dodo, and a tripod as rare as its egg… Arm yourself with an F/6 lens, and snap as fast as you like’ (1905a, p 390). By this time, both cycling and photography had developed into more practical and simple to operate machines, and were within the reach of a wider class of people. The roll film had brought photography to many whose interest was not in artistic expression but, rather, in recording family, friends or events of personal value: as has been extensively discussed, this led to a new kind of photograph, the snapshot. The photographs that Wheelman encouraged cyclists to take, however, were not without artistic intent. In the column, which ran in the AP during the summer season from 1905 to 1908, Wheelman made clear that the pursuit ought to be ‘pictorial photography’, and that a photographer who cycled was not a ‘mere amateurish snapper’ (1905b, p 105). Yet, by advising photographers to avoid long exposure times and to work with what would have been a rapid lens, Wheelman also acknowledged that the modus operandi of a photographer was somehow changing. The tripod, which stood for a contemplative study of the object to be photographed, appeared to be unfit ‘in this hurrisome twentieth century’: as I have argued in this article, the fast pace of modernity fostered amongst cyclists a desire for new ways to engage with, and to represent, such new visual experiences. We can then say that the acceleration of the age, which the new mobility of cycling so aptly embodied, anticipated the immediacy of the snapshot by revealing the limitations of established photographic practices and apparatuses in meeting the desires of a modern, moving, gaze. While Wheelman continued to promote pictorialism, photographers who did not share the same anxiety about cultural recognition were able to develop a new visual language attuned to the experience and temporality of modernity.

The visual accounts of photographers who, starting in the late 1870s, began cycling, can be understood in this way as the expression of a new experience of being in the modern world that was fully realised visually only with the advent of the roll film and, with it, the compact camera. As Edwards notes, ‘the way in which photography has been understood almost exclusively as a visual system’ elides the fact that photography is ‘a complex and embodied cultural process of which the photographs themselves are only the final outcome’ (2014, p 179). In this article I have hopefully demonstrated that paying attention to the ideological and historical conditions for the production of photographers, and not simply of photographs, can contribute to our understanding of the significance that photography, as more than just a visual system, has had for modern life.

Acknowledgments

Earlier drafts of part of this article were presented at the Institute of Historical Research Transport and Mobility History Research Seminar, and at the Royal College of Art/V&A Research Seminar, in 2018. I should like to thank the participants in both places for their insightful comments and probing questions as these helped me to refine the ideas presented. My thanks also to Liz Wood, Assistant Archivist at the Modern Records Centre, University of Warwick, for her kind assistance in tracing key sources; and to Lorne Shields for his generosity in sharing his cycling photographica collection and knowledge on the subject with me.

Tags

Footnotes

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text