The Panstereomachia, Madame Tussaud’s and the Heraldic Exhibition: the art and science of displaying the medieval past in nineteenth-century London

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/181011

Abstract

‘Panstereomachia. This title, as long as a man’s arm, belongs to an exhibition of a novel kind, which was opened on Monday, 19th June, 1826.’ Devised by Charles Bullock, the exhibit featured a large model of the ‘memorable battle of Poictiers’ where the English hero, Edward the Black Prince, defeated French forces in 1356[1] The exhibit spoke to a burgeoning market for historically-themed exhibitions and a growing fascination with the Middle Ages in the nineteenth century. A key selling point of the exhibit was its mysterious name which alluded to a new type of exhibition experience. Yet the Panstereomachia was only one of many ‘educational’ exhibits which employed old and new technology to bring the past to life in order to edify and entertain new consumer audiences.

This essay will trace three exhibitions across the nineteenth century to assess how exhibitors drew on science and technology to offer competing visions of the medieval past. Moving from the Panstereomachia model, it will look at the introduction of medieval-themed figures and tableaux at Madame Tussaud’s from the mid nineteenth century before exploring the 1894 Heraldic Exhibition and the debate over the preservation of medieval artefacts. Underpinning this discussion are two key questions: What role did technology play in the ways in which people exhibited and accessed the past historically? How can visual and material culture inform our understanding of shifting notions of the Middle Ages?

Keywords

heritage, history of exhibitions, London, medievalism, nineteenth century, science and art, Technology, Visual and material culture

Introduction

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/Historians have called the nineteenth century the age of display – a period when exhibitions and museums vied for the public’s attention in order to edify and entertain. Altick’s classic study of the Shows of London illustrates how the city became a hub for these diverse exhibitions as a centre of culture and innovation (Altick, 1978). Underpinning many of these exhibitions was their use and promotion of technology, from the magic lantern to what Iwan Morus has called ‘electrical entertainments’ (Morus, 2005, p 113). Scholars exploring the popularisation of science in the nineteenth century have highlighted the impact of technology on its dissemination and commercialisation (Lightman, 2007; Fyfe and Lightman, 2007; Berkowitz and Lightman, 2017; Kember, Plunkett and Sullivan, 2012). They have pinpointed the late Georgian and Victorian eras as a critical time in exhibition development, with technology instrumental in shaping scientific narratives.

Yet, scientific exhibitions were only one part of the competitive world of London shows. In her work, Billie Melman demonstrates how a new fascination with the past underpinned by the commercialisation and democratisation of history in the nineteenth century led to an abundance of exhibitions (Melman, 2006; Melman, 2012, p 79). In London, visitors could explore panorama exhibitions, viewing large scale depictions of famous battles such as Waterloo and Agincourt, or peep hole displays that offered only brief glimpses of pictures. Magic lantern shows brought home images of historical sites while more experiential exhibitions had visitors walk through themed halls to see artefacts up close. New work on these history-themed shows has revealed how they are vital in examining the cultural work of different pasts in British society from the medieval to the Stuart, illustrating shifting audiences for the past and exposing competing narratives of history. While historians have acknowledged the use of technology as integral to the display and popularisation of the past, the impact of technology on discourses of national identity and narratives in these exhibitions remains unexplored. This paper uses a broad definition of technology which includes both ‘old’ (methods and materials developed that had been used before the nineteenth century), including wax models and ‘technological’ conservation of objects, and ‘new’ (those that developed in the nineteenth century or recent to it) such as gas and electric lighting.

This essay seeks to rectify this gap by examining the role of old and new technology on the representation and reception of the past through an exploration of three scene-setting nineteenth-century exhibitions: the Panstereomachia (an exhibition of the medieval battle of Poitiers); Madame Tussaud’s wax museum with its historical figures; and, later, historical tableaux and the 1894 Heraldic Exhibition. These exhibitions are ideal case studies for such an investigation. First, as London-based exhibitions that cut across the early, mid and late nineteenth centuries, they enable comparisons between diverse approaches over the same period and differences in historical narratives. The 1826–27 Panstereomachia exhibition, which used spectacle and novelty for elite and middle-class audiences can be compared with early Tussaud’s from the 1830s, which also used spectacle but provided mass entertainment. In turn, Tussaud’s introduction of historical tableaux in the 1890s offers a fruitful comparison with the 1894 Heraldic Exhibition; each shows a different approach to institutional authority and authenticity in its treatment and display of objects. Second, these exhibitions enable an exploration of different uses of the medieval past. The nineteenth century was known as the age of medievalism, when the fascination with the medieval past reached its height; however, by the mid-late Victorian era, the medieval was increasingly contested (Gribling, 2017). Focusing on two medieval pasts – the Anglo-Saxon and the late medieval – we can assess the shifting work of these pasts in British culture. How do these exhibitions offer new perspectives on the uses of the medieval past and how did they confirm or challenge other narratives about the past that were circulating in academic and popular culture? Third, each exhibition represents an innovative use of technology – from the Panstereomachia’s focus on novelty and science in the early nineteenth century to Madame Tussaud’s waxworks and its move from gas to electric lighting in the Victorian era to conservation efforts on artefacts prior to the Heraldic Exhibition. Taken together, these three exhibitions expose how technology influenced and reshaped historical narratives, altering our understanding of how nineteenth-century Britons displayed, understood, and engaged with the past.

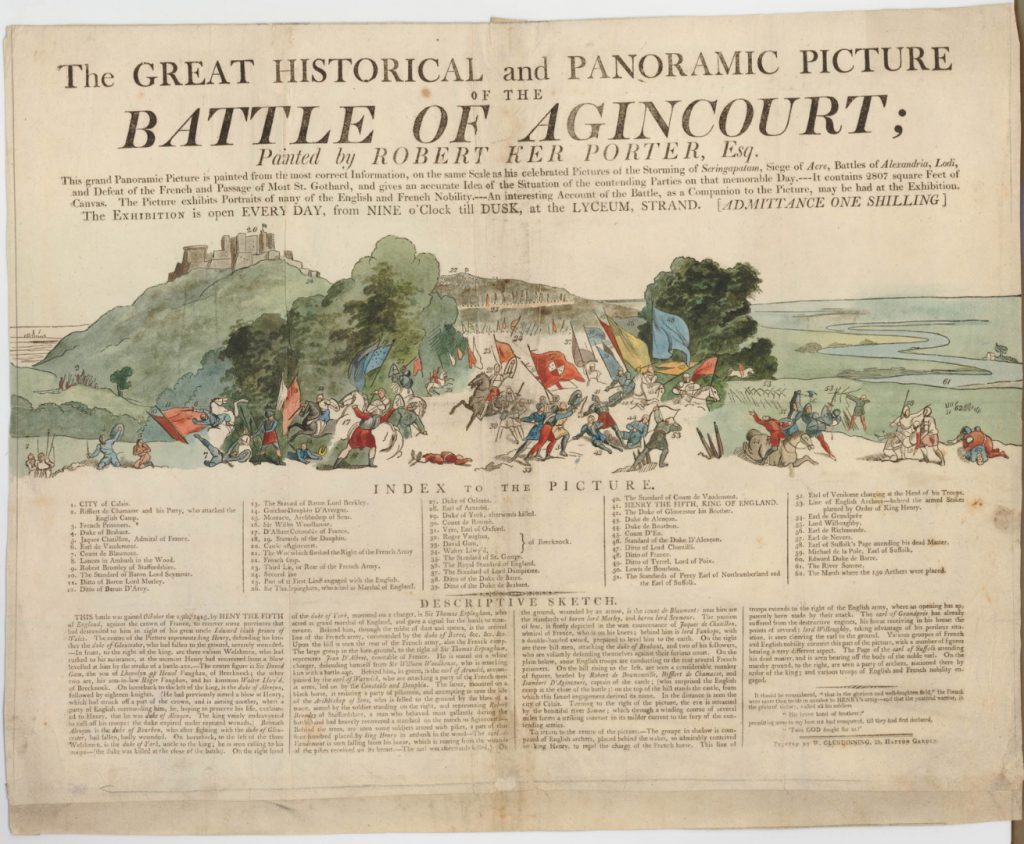

Mr Bullock’s Panstereomachia: novelty, victory and ‘True History’

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/181011/002In the early nineteenth century, the vibrant market for history products and events catered both to the aristocracy and to an aspirational middle class as part of a culture of improvement and a burgeoning nationalism. The act of learning about history and a renewed interest in the English national past was an integral part of this culture, and the narratives espoused in history exhibitions, shows and lectures (on a variety of pasts from Celtic to Tudor or medieval to Stuart) were anchored in discussions about character and patriotism. On the one hand, historians such as David Hume and Henry Hallam offered their scholarly visions of the past, while on the other hand, more commercial exhibits played with these histories as ‘respectable’ entertainment, at once complementing and challenging more traditional versions. History exhibitions were a central part of the larger market for edification and entertainment, and London had a wealth of potential sites where exhibitors competed to capture the public’s attention from the Strand and Leicester Square to Oxford and Regent Streets (Altick, 1978; Roberts 2017). A city of London’s size proved an ideal site for technological experimentation and exhibition innovation. One such exhibit was Robert Ker Porter’s Agincourt panorama first displayed to the public in 1805 at the Lyceum on the Strand (Curry, 2015, pp 171–2).[2] Visitors were invited to stand on a platform and look out at a large-scale image of the medieval battle where Henry V and his army defeated the French. Its presence speaks to a larger revival of interest in medieval battles and heroes underpinned by Anglo-French tensions, yet it used technology, in this case, light and large-scale imagery to make viewers feel as if they were immersed in the battle.

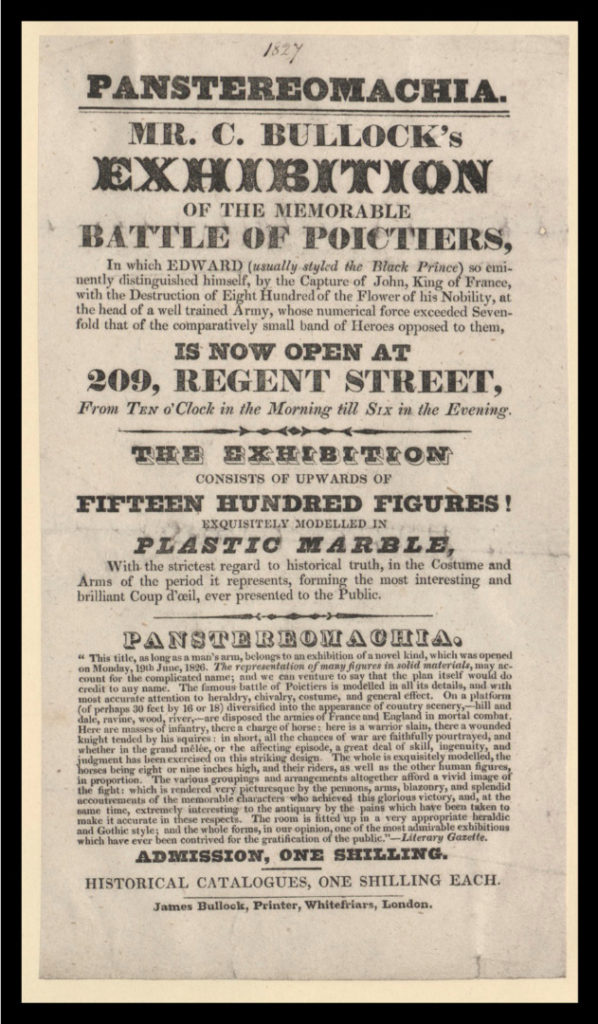

The Panstereomachia chimed with these new types of historical experiences[3] In 1826, Mr Bullock opened his exhibit at 209 Regent Street – a famous venue for larger scale model works and pictures with a known upper and middle-class clientele. For the price of a shilling, visitors could view a model on a platform, approximately ‘30 foot by 16 or 18’, of the fourteenth-century battle of Poitiers, when the English chivalric hero Edward the Black Prince fought and won a key battle, capturing King John II of France in the first part of the Hundred Years’ War[4] A key selling point of the exhibition was its mysterious name, which alluded to a new type of experience. Indeed, the name itself was invented by the proprietor and speaks to the ways in which early nineteenth-century exhibitors used ‘pseudo-scientific’ and ‘learned’ names to attract customers. The name was translated into Greek in the exhibition guide (Glasse, 1830, pp 155–6), [5] although The Times poked fun at it, calling it a picto-mechanical representation and boasting that, like Mr Bullock, it too could also coin a name (1826a; Altick, 1978, p 215).

The exhibition reveals the increasing commercialisation of the past and a burgeoning collecting culture. The material used to create the 1,500 ‘plastic-marble figures’ – including the Black Prince and King John of France – was a mystery to viewers, and the model has since been lost. However, it is likely that the use of the term ‘plastic marble’ (implying a new material) to describe the figures was part of the selling tactic. Colburn’s Magazine was keen to remind visitors that the figures were similar to those sold in the curiosity shops (1827). These exhibitions were commercial enterprises where visitors could buy a special guide available for an additional shilling. Bullock advertised the fact that the models were for sale both individually and in groups for viewers to take home and display[6]

The Panstereomachia offers insight into changing attitudes towards the medieval past. In the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars, exhibitors capitalised on a burgeoning interest in the Middle Ages and promoted the Black Prince’s earlier victories against the French as a source of national pride and celebration. Bullock’s exhibition tapped into an antiquarian interest in medieval arms and armour, a popular enthusiasm for chivalry and romance spurred on by the novels of Walter Scott, and a renewed fascination with ‘authentic’ medieval ‘authorities’ such as Jean Froissart (whose Chronicles brought to life the sights and sounds of the fourteenth century, particularly its battles and the exploits of knights). Bullock was keen to promote his figures as both accurate and edifying to attract crowds interested in improvement and novelty. To craft the costumes, weapons and heraldic insignia, he used Samuel Meyrick’s authoritative Critical Inquiry into Antient Armour as well as information from those whose ‘ancestors had fought in the battle’ (Bullock, 1826, p 5; Meyrick, 1824; Froissart, this edition, 1803–1805). Historian Billie Melman showcases a hallmark of these nineteenth century popular exhibitions was their claim to verisimilitude: ‘to be veritable, history had to be seen as “lifelike”, authentic, and first-hand’ (Melman, 2012, p 80). The Panstereomachia, with its use of historical documents and first-hand accounts, exemplifies this premise.

To capture the romance and excitement of the day, the exhibitor relied heavily on Froissart’s depiction of events. His model portrayed a key moment near the end of the battle when ‘friends and foes were…intermixed’ and the French were in retreat towards the city of Poitiers, represented by a painted background (Bullock, 1826, p 44). The exhibition room itself was designed to evoke the age of Edward III; the entrance bore the banners of the English heroes James Audley and John Chandos, and the interior room was painted in a gothic-style architecture with the ‘armorial bearings of the noblemen and gentlemen who distinguished themselves in the battle’ (Bullock, 1826, p 44). Advertisements and the guide highlighted the Poitiers Panstereomachia as a brilliant ‘display of British military achievements’[7] Visitors were encouraged to compare the heroic medieval battle with the ‘victories…in succeeding ages’ – recalling their ancestors’ feats during the Napoleonic Wars (Bullock, 1826, p 4).

Newspapers highlighted the broad appeal of the exhibition from antiquaries to the general public, including the array of ‘holiday-searchers after strange sights’ (1827). They focused on the model’s effectiveness as an object of edification and entertainment, noting its blend of ‘“true history” and romance’ (1827). [8] In particular, newspapers emphasised how the detailed costumes, the arms and armour of the knights, the models of the soldiers, the weapons that peppered the field, and the topography made the model a useful pedagogical tool (1827). According to the Literary Gazette, Bullock’s arrangement of the figures fostered the feeling of being in the midst of a ‘mortal combat’ between the French and English[9] although the critic in The Times found it difficult to imagine why the heroic Black Prince was placed under a tree and not in the centre of the fight (1826a). The Black Prince’s placement illustrates how these popular exhibitions could circumvent expectations. Assessing the value of the model, Colburn’s Magazine suggested that the exhibition would not provide any new details to those knowledgeable of the events, but ‘to all others (and Mr. Bullock will probably consider these “others” a most satisfying majority, if he can but secure their visits) it will probably convey a better notion of the event in question than they ever had before; and one that will stay by them longer’ (1827). The exhibition illustrates how Bullock capitalised on the popular taste for medieval victories and novelty to attract visitors to the Panstereomachia, establishing his place in the competitive market of London shows. The Panstereomachia blended technology and history as technology was an integral part in creating the historical experience – present in its advertising through its invented name, in its mysterious ‘plastic-marble’ material, and in its final creation of the birds-eye model of the battle.

Madame Tussaud’s: lights, wax, action

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/181011/003A second exhibition brings us to the middle of the Victorian era to Madame Tussaud’s wax museum. Marie Tussaud arrived in London in 1802 and travelled around Britain exhibiting her wax figures before establishing a more permanent exhibition on Baker Street (in a building called the Baker Street Bazaar) in the 1830s. In 1884, the collection was moved nearby to its final premises on Marylebone Road. Madame Tussaud’s was a popular London attraction. Billed as a respectable, entertaining and edifying experience, it attracted a wide-ranging audience of adult and child customers and even had its own orchestra (Pilbeam, 2002, p 93; Shepherd, 1841, p 138; 1890; Sala, 1905, p 7). [10] The museum was also easily accessible, with Baker Street Station opening in 1863[11]

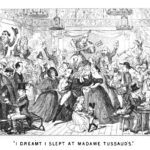

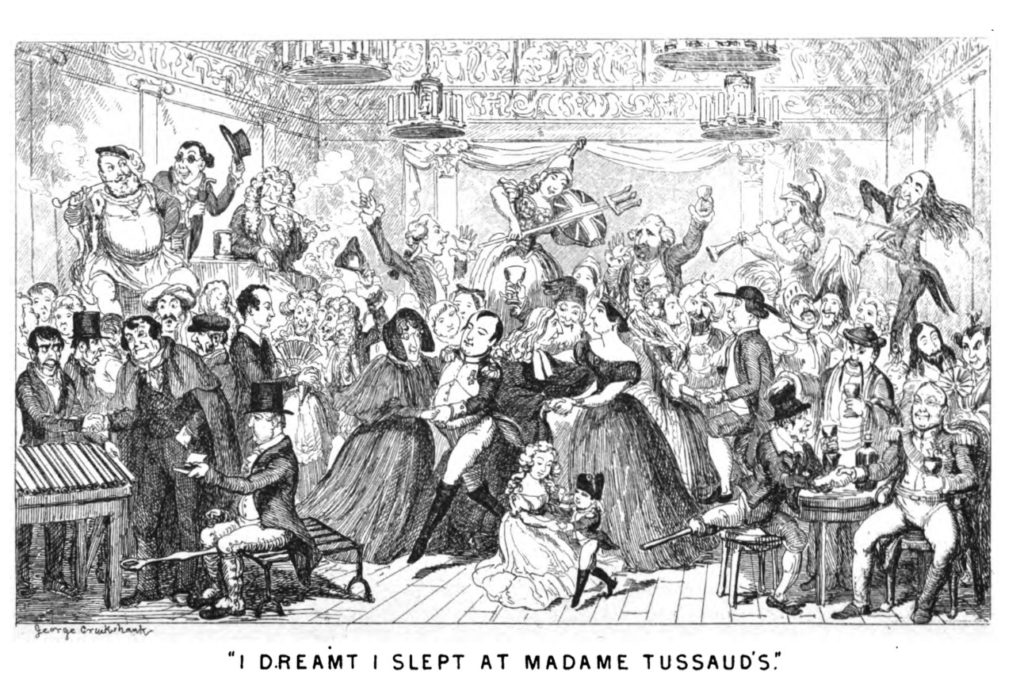

Tussaud’s relied on both old and new technology to create their exhibits. Wax figures had been modelled since antiquity and were often part of funeral rites which would offer lifelike effigies of deceased relatives[12] Wax shows were popular in the nineteenth century and catered to a variety of tastes, from the anatomical models at circuses to exhibitions of royal figures and celebrities (Pilbeam, 2002, pp 131–52). Tussaud’s distinguished itself from its competition with its well-crafted and lifelike figures, its sheer size, and its appeal to a wide range of visitors. Here visitors were encouraged to get up close to the famous, as well as the infamous (who were located in the Chamber of Horrors). The lifelike appearance of the figures, their closeness and Tussaud’s strategic use of mirrors added to the effect of blurring the distance between spectator and spectacle. The realistic nature of the figures was the subject of a cartoon by George Cruikshank in the Comic Almanack (1847) entitled ‘Last night I dreamt I slept at Madame Tussaud’s’ (Thackeray et al, 1844–1853, p 167). In a Night at the Museum moment, the cartoon depicted the figures coming to life after the last visitors had left. Here, Henry VIII, Elizabeth I, Charles I, Pitt the Younger, Britannia and the figure of Queen Victoria conversed and danced.

Tussaud’s also embraced more recent technologies like gas lighting, which had only been adopted in the early nineteenth century before it became more common in the public buildings and streets of mid-nineteenth-century London (1884).[13] Tussaud’s used gas lights extensively to illuminate figures and to create eerie light effects in the Chamber of Horrors by dimming the lights and casting shadows. While Tussaud’s use of artificial lighting impressed many visitors, American Benjamin Moran (part of the US legation later the US embassy) had a more negative picture: ‘Wretched figures of more wretched kings and queens are judiciously disposed for exhibition, and the spangles on their faded robes glitter in the gaslight, and astonish and delight the loyal crowd’ (Moran, 1853, p 217).

In Madame Tussaud’s wax museum, technology was also used to bring visitors closer to the more distant past. The exhibition’s focus on the British past, and royal figures, can be linked to its desire to market itself as an educational exhibit (Gribling, 2018, pp 421–38). In the mid-Victorian era, Tussaud’s set about major additions to its English royal figures, and advertisements highlighted the relevance of these figures for schoolchildren, aiding them in their ‘historical studies’ and enabling them to engage with royal heroes and villains that featured heavily in their history books. By the 1860s, advertisements boasted that Tussaud’s now contained every monarch from William the Conqueror to Queen Victoria. Tussaud’s played into this market, encouraging children to go up to and touch the figures and thus supplementing guidebooks and exhibition texts which explained their historical importance. The Daily Telegraph noted that ‘Tussaud’s…figures were so correctly portrayed and dressed that they [were] an ideal aid for teachers’ (1883).

In the 1850s and 1860s, Tussaud’s royal figures underwent a major expansion when a number of new characters were added, including many from the Middle Ages, such as King John, Richard I, Edward III and the Black Prince. Focusing on two late-medieval figures, King John and Edward the Black Prince, we can see how the types of narratives espoused by Tussaud’s complemented and played with the narratives and royal characters presented in children’s school books and novels. A wax statue of the warrior Edward the Black Prince placed in Tussaud’s in 1862 had the prince decked in a ‘suit of gilt armour’ with his sword by his side[14] Tussaud’s invested heavily in their models and their costumes, seeing this as integral to their character’s image[15] An advert in Le Follet (a ladies fashionable magazine) stated that the costumes were composed by careful study of ancient manuscripts (1863). It is clear that the Black Prince’s statue was also modelled on his effigy in Canterbury Cathedral – itself a great example of medieval craftsmanship – illustrating how Victorian imaginings of characters in the age of chivalry were often indebted to medieval constructions. Guidebooks presented the prince as a heroic conqueror, in keeping with other images of Edward that circulated in histories and adventure stories[16]

In contrast, Tussaud’s presented a more negative image of King John, putting into wax visions of the king previously circulated in popular histories for children like Mrs Markham’s History of England and Maria Callcott’s Little Arthur’s History of England (Penrose, 1823; Callcott, 1835). According to Little Arthur’s, John’s reign ‘was a very bad one for England, for John was neither so wise as his father, nor so brave as his brother. Besides he was very cruel’ (Callcott, 1835, p 140). The guidebook for children A Visit to Madame Tussaud’s noted that, ‘That fierce looking man is King John. He was a very bad man, and the worst King that England has ever had. The Barons were so angry with him that they sent to offer his throne to the Dauphin of France, and he was just coming over to take it, when John, who was staying at a convent, was poisoned by one of the monks and died’ (Madame Tussaud and Sons’ Exhibition, 1890s, p 5). It appears that the model of King John was effective; the author of ‘An American Girl in London’ stating ‘I could not have believed it possible to put such a thoroughly bad temper into wax’ (1890). Tussaud’s ensured that their waxworks’ expressions, body language, and costumes all contributed to their overall vision of the character.

While Tussaud’s reinforced popular visions of Edward and John, it also circumvented these traditional narratives of history through its placement of other historical royals. In Tussaud’s, the figures were not always in chronological order and displays often highlighted certain royals over others giving them more privileged positions[17] For example, the 1873 catalogue shows how a number of royals – including Edward III, the Black Prince, Henry V and Henry VIII and his wives – were placed in the Large Room as opposed to the Hall of Kings (Madame Tussaud and Sons’ Exhibition, 1873, p v). The placement of these characters in the first room visitors would enter suggests that these figures were used to draw in visitors. Yet, it also speaks to the continued interest in the late medieval and Tudor royals in Victorian culture (Mandler 2011; Melman, 2006); Tussaud’s kept track of which figures drew the crowds, and constantly moved figures to account for changing popular tastes.

Tussaud’s royal exhibits continued to be popular into the late Victorian era, shaping perceptions of historical characters as well as contemporary characters, including Queen Victoria and her family. Indeed, Tussaud’s constantly updated their figures – both adding new ones and cleaning and touching up their other models. In his behind-the-scenes tour of the waxworks, the author of an article in the Million noted: ‘In the dressing-room the workers were engaged upon a new costume for Richard Coeur de Lion, which consisted of a white silk shirt with a red cross embroidered upon it, and a blue velvet cloak to be worn over his armour’ with a dressmaker stating ‘“their clothes have to be renewed every seven years – they get so rotten”’ (1893). Richard’s costume was integral to Tussaud’s projection of the king as a romantic crusader and brave Christian warrior (Madame Tussaud and Sons’ Exhibition, 1890s, p 5). However, as the nineteenth century progressed, this vision competed with more negative depictions of Richard I in literature and histories as a ruler who abandoned his country and embarked on a costly war (Gillingham, 2004; Gribling, 2017, pp 68–9).

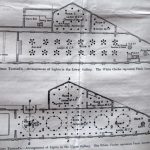

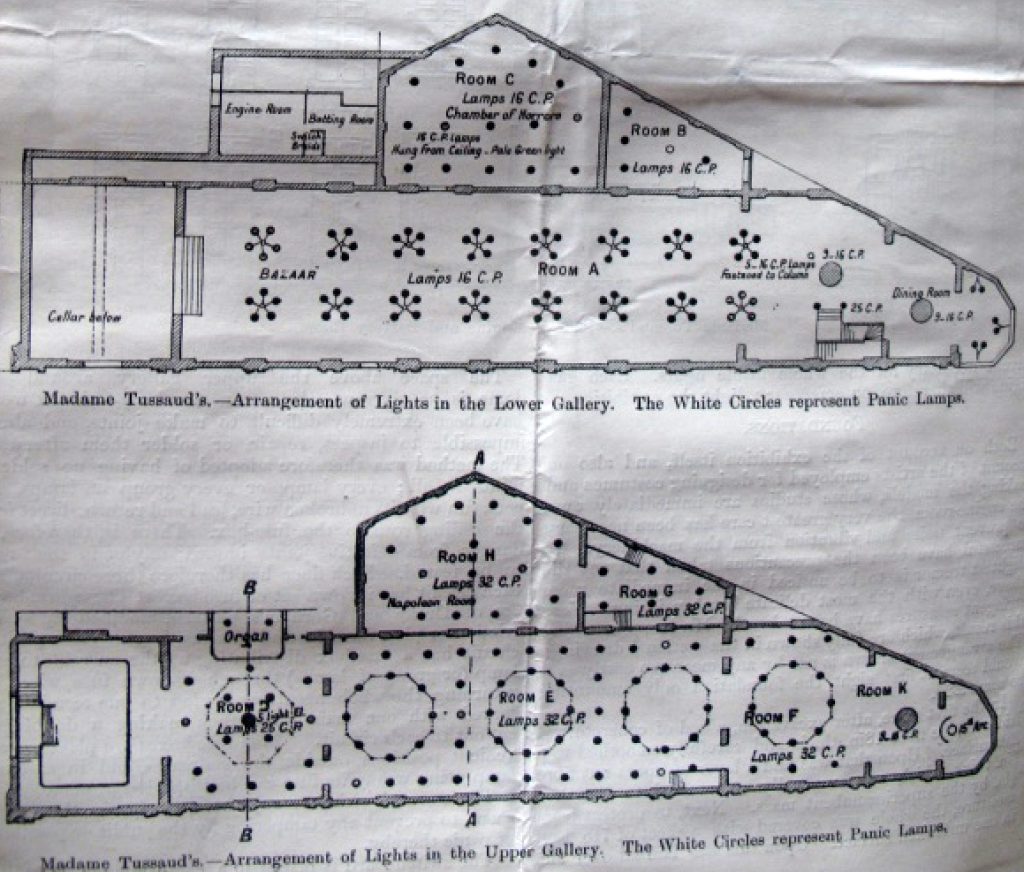

By the late nineteenth century, Tussaud’s was also investing heavily in their tableaux, which included key scenes from the British past. They used the new technology of electric lighting to enhance their exhibitions and showcase particular stories. Tussaud’s replacement of gas with electric lighting in November 1890 heralded a new era in museum display[19] In an article published 11 June 1897, the periodical Electricity highlighted how Tussaud’s used the new technology to transform the way visitors experienced three medieval-themed tableaux: ‘Alfred the Great in the Neat-herd’s cottage’, ‘Harold losing the Battle of Hastings’ and ‘King John signing the Magna Charta’. The story of a distracted Alfred who burnt the cakes and was chastised by a peasant woman was well-known in Victorian England (Parker, 2007, pp 103–107). Here, Tussaud used electricity to make a fire that ‘glows with a ruddy glare’. The author of Electricity noted rather humorously that the King Alfred exhibit showcased the ‘art of electric cooking, for he bakes, or rather burns, the time-honoured cakes’ (1897, p 281). The Sporting Review argued that the new lighting also made the figures appear more lifelike than they had under the gaslight (1890a). Those looking at the body of Harold after he had been struck by an arrow could now see clearly ‘the deathly pallor of the dead king’s face’ being in ‘striking contrast to those of the seekers’ adding to the gravity of the scene (1897, p 281). The ‘Magna Charta’ tableau used 56 lamps so that John’s signing appeared to be ‘transacted under the blaze of the mid-day sun…and so that no tell-tale shadows shall reveal their presence’ (1897, p 281). Thus, the introduction of electricity provoked changes in design as well as interpretation.

In their tableaux, Tussaud’s used technology to shape historical narratives about the Anglo-Saxon and late medieval pasts and royals. In the ‘Harold’ tableau, staging and backdrops were used to draw viewers into the solemn scene: Harold’s body has just been discovered by his love Edith and two monks who will eventually take it to be buried in Waltham Abbey. The tableau depicts the last Anglo-Saxon king as a tragic figure with the guidebook entry citing his tomb inscription Hic ‘jacet’ Haroldus infelix – ‘here lies Harold the unfortunate’ (Sala, 1905, p 80). In the Alfred tableau, Tussaud’s used electricity to make Alfred’s fire a focal point with the Neatherd’s wife, the Neatherd and Alfred all looking at the cakes. Tussaud’s guidebook highlighted both the humour of the king being reprimanded and the reason for his distraction – his conflict with the Danes. The presence of these two tableaux in the late nineteenth century illustrates how the museum played into the wider Victorian Anglo-Saxon revival. Alfred was promoted as an exemplar of the Anglo-Saxon race and was the subject of numerous histories, plays and even a major celebration in Winchester in 1901 (Parker, 2007). For the Victorians, Harold’s death at the hands of William the Conqueror’s Norman army marked a turning point in English history. While Harold’s tableau highlights the king’s tragic death, Simmons suggests this scene could act as a reminder of England’s eventual triumph as the Victorians saw themselves as ‘reversing the conquest’ by reclaiming their Anglo-Saxon heritage (Simmons, 1990, p 151).

In contrast, ‘King John signing the Magna Charta’ clarifies perceptions of the late medieval past. Tussaud’s used lighting to create the sunlit outdoor scene in Runnymede meadow and to draw attention to the cowed monarch[20] The 1905 guidebook highlighted how this tableau was meant to be viewed: ‘The expression on King John’s face, of mingled rage and humiliation, is best seen by the visitor when standing well to the left of the group. It will then be perceived that he is apparently speaking to Fitz-Walter, whom we may suppose he is upbraiding for depriving him the royal authority and power he had so disgracefully abused’ (Sala, 1905, pp 87–88). While Tussaud’s used the tableau to promote the view of John as a villain, its presence was also part of a wider Victorian and early Edwardian celebration of Magna Carta (in art, literature, histories and performances); the 1215 charter was projected as a marker of constitutional progress whereby the liberties of the people were secured (Breay and Harrison, 2015). By the late nineteenth century, bolstered by their additions of new historical kings and queens and historically-themed tableaux, Tussaud’s continued their drive to promote themselves as an essential educational experience for all ages (Gribling, 2018), straddling the roles of educator and entertainer for the masses. Tussaud’s approach to history can be contrasted with the Heraldic Exhibition of 1894, which moved from mass entertainment to new and competing ideas about historical authenticity and authority, and a new interest in the Middle Ages as heritage.

The Heraldic Exhibition of 1894: preserving Britain’s national heritage

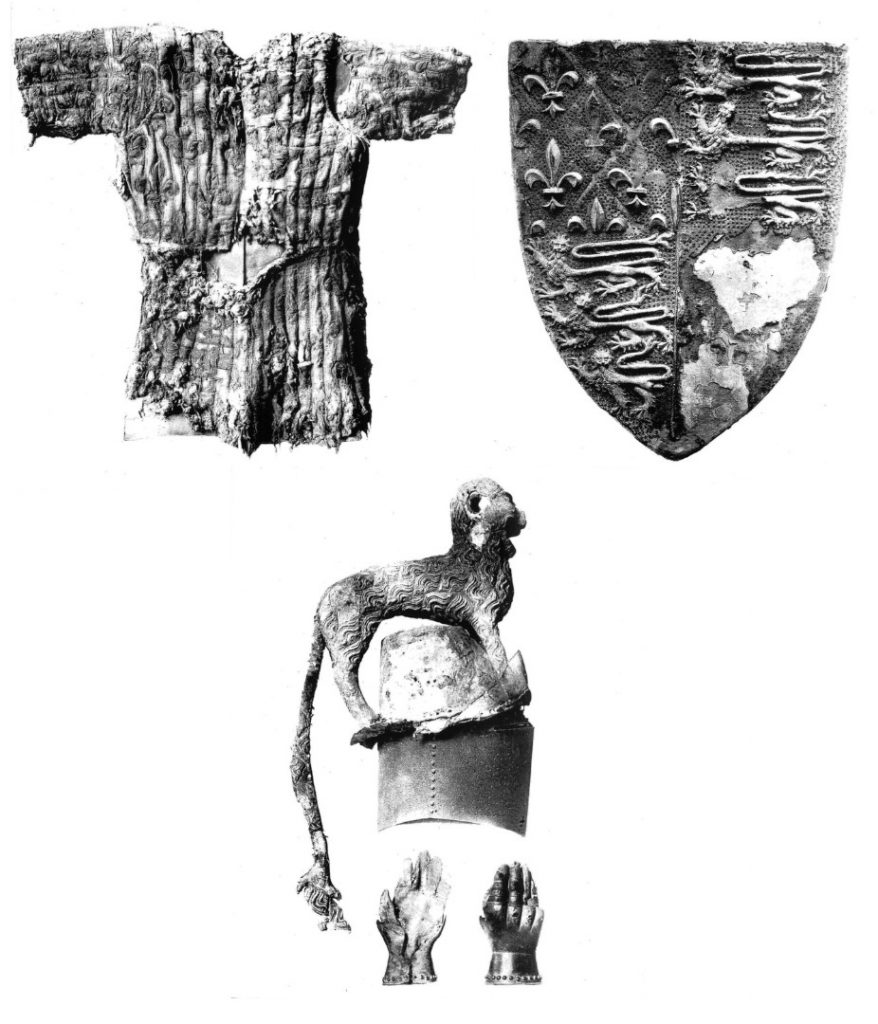

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/181011/004A third exhibition, the Heraldic Exhibition, illustrates a growing desire at the end of the nineteenth century to preserve medieval artefacts as important parts of Britain’s national heritage. From 31 May to 13 June the Society of Antiquaries of London held a Heraldic Exhibition at Burlington House. The exhibition focused on English heraldry and included a wide range of objects from armour, textiles and pottery to medallions, illuminated manuscripts and playing cards. While the exhibit featured objects from the Middle Ages to contemporary times, medieval objects played a prominent role. The exhibition captivated the public and engaged a number of prestigious guests including the Prince of Wales, Albert Edward and his brother Prince Alfred (1894; 1894a). One of the highlights of the exhibition was the Black Prince’s relics (also known as his achievements) – his helm, crest, gauntlets, shield and jupon – which were on loan from Canterbury Cathedral (1894; 1894a). This was the first time the Cathedral had allowed them to be moved since their installation above his tomb after the Black Prince’s death in 1376 (Society of Antiquaries of London, 1896, Plates I-III; 1894a). The Black Prince’s relics were placed in a prominent position on the ground floor next to the shield of another famous English warrior, Henry V, on loan from Westminster Abbey (Society of Antiquaries of London, 1896, p 1; Society of Antiquaries of London, Catalogue, 1894, p 8). The exhibition drew public attention to the state of decay of the Black Prince’s relics, especially the jupon or coat-armour.

While there had been much antiquarian interest in the Black Prince’s tomb from the seventeenth to the early nineteenth centuries, by the late nineteenth century, discussions increasingly focused on the desire to protect Edward’s achievements. In 1890, Albert Heuthing (a member of one of the many London antiquary clubs) wrote a letter to the Dean of Canterbury Cathedral asking the Cathedral to consider removing the military achievements from above the prince’s tomb and placing them under glass to stop their decay. Heuthing argued that there were few examples of military accoutrements existing from the fourteenth century and he appealed to the Cathedral about the national significance of Edward’s military possessions, suggesting that the achievements were likely ‘worn by [the Black Prince] at the scenes of his prowess’[21] This was not the first time that Heuthing had expressed concern about the prince’s tomb. In 1872 he had written a letter which was published in The Times after a fire had broken out in Canterbury Cathedral[22] In it, he stressed the significance of the tomb as the chief memorial to Edward and his victories, proclaiming it the ‘one great historical monument’ where viewers could go to celebrate the English victories at Crécy and Poitiers (1872).

The campaign to preserve the Black Prince’s relics gained national attention in the lead up to the Heraldic Exhibition when the Society of Antiquaries took up the cause. Upon seeing the relics first hand, the Society began to campaign for their restoration and preservation, citing their historical significance as ‘national heirlooms’[23] Thus, the Heraldic Exhibition was not just about the display of the relics, but also about bringing them to London so that they could undergo conservation efforts.

The Society was well aware of the decay of the relics; in a letter from W H St John Hope (assistant secretary of the society and expert on heraldry) to Canon Holland, Hope noted the poor condition of the beam above the tomb that held the relics, noting that ‘worms may have eaten’ it[24] He also expressed his fears that the surcoat needed immediate attention to see if it had moths due to its poor condition: ‘It is perfectly certain that unless something is done and soon to preserve these priceless relics from further rapid decay, they will inevitably fall to pieces at no distant date.’[25] When discussing the transfer of the relics to London, Hope informed the Cathedral that having the relics in London would also enable the society and experts to assess the relics for damage: ‘they would receive the best treatment’ from experts at the British Museum and the South Kensington Museum’ and he pressed the importance of conservation efforts ‘so that these historical relics at Canterbury be preserved to charm and interest future generations’[26]

Once in London, repairs to the relics were done under the auspices the Society of Antiquaries. Much of the work centred on the jupon, which was missing parts, and was faded and fragile. A ‘fine pure silk net’ was used to conserve the piece by supporting the remaining fabric[27] A 1923 ‘Report upon the Present Conditions of the Achievements’ described the 1894 repairs, noting the introduction of tacking to prevent the wool stuffing from falling out. Repairs to the Black Prince’s relics were executed to keep the ‘more ragged parts of several items in position’ while stitches and brass nails were used in the jupon to hold things together[28] Here, the society used old and new conservation techniques in order to preserve the past for future generations. Both the Society and the Cathedral noted the importance of preserving these artefacts, an early example of a jupon representing a significant part of British heritage through its association with England’s hero, the Black Prince.

The Society of Antiquaries also campaigned for the relics to be placed under glass on their return to the Cathedral[29] In a letter to the Dean of Canterbury, Society secretary Charles H Read mentioned that the plan even had the support of royalty – with ‘The Prince of Wales and the Duke of Saxe Coburg (Prince Alfred) being particularly interested in [Edward’s relics], and expressing hope that they might be protected from further injury…the Prince…was strongly in favour of the plan…that these national heirlooms should be placed under glass, so as to prevent the possibility of further damage’[30] The Society’s insistence on a glass case for the relics may have been about preservation; it was especially concerned about the amount of dust on the relics. However, advocating placing the items under glass may have also been to preserve the artefacts in another way: to protect them from Victorian souvenir thieves keen to take home a piece of history. Indeed, in a letter to the Cathedral, Read expressed fears that the items would be ‘lost’[31]

The Cathedral allowed for restoration of the Black Prince’s relics but resisted removing them from their place above Edward’s tomb once they had returned from London. The relics were not placed under glass until the late twentieth century, and today replicas are in their place above the tomb. From letters and reports by the Cathedral into the early twentieth century, it is apparent that they felt that removing the achievements from their original position above the prince’s tomb would take away from the overall impact of the monument. In the late nineteenth century, the Cathedral’s desire to display the Black Prince’s relics in their original position – allowing viewers to experience them ‘authentically’, as visitors would have since the fourteenth century – came into conflict with the Society of Antiquaries, who lobbied to remove them from above the tomb and preserve them under glass[32]

Conclusions

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/181011/005Taken together, the Panstereomachia, Madame Tussaud’s and the Heraldic Exhibition offer a fresh perspective on how technology impacted public encounters with the medieval past in the nineteenth century, illuminating the intersections between visual and textual worlds and scholarly and popular perceptions. All three exhibitions offer valuable insight into the role of technology in shaping visitor experiences of the medieval past. The Panstereomachia and Madame Tussaud’s wax museum illustrate how, in the rich market for history, exhibitors relied on technology to entice and engage visitors. Newspapers and advertisements highlighted the Panstereomachia’s ‘scientific’ name and ‘plastic marble’ figures to claim novelty, and promoted Tussaud’s use of wax models to bring historical figures to life. Technology also proved critical as a means for exhibitors to create new experiences and ways to access the past. The proprietor of the Panstereomachia used technology to enable visitors to become closer to a lost past by creating a birds-eye view of the battle of Poitiers, while Tussaud’s used technology to revive the past through their character models, and later through tableaux that enabled visitors to meet historical figures or witness ‘significant’ events. The introduction of gas (and later electric) lighting was critical in shaping narratives and experiences of Harold’s demise, Alfred’s cakes, and the Magna Carta. Finally, the conservation of the Black Prince’s relics for the Heraldic Exhibition shows how technology can also be used to preserve the past, highlighting the role of the historical object itself as central to exhibits. The Black Prince’s relics became stand-ins for his battles and a place to ruminate about his reputation as a heroic individual. The exhibition links restored artefacts with the uses of the past, highlighting the centrality of the ‘authentic’ object in shaping visitor experiences.

At the same time, the attractions expose how exhibitors played with history and historical narratives about the Anglo-Saxon and late medieval pasts, complementing as well as contesting versions found in history books. This essay’s focus on the characters and exploits of the Anglo-Saxon and late medieval royals sheds light on the reputations of Harold, Alfred, Richard I, John, and Edward the Black Prince. While the Panstereomachia echoed early nineteenth century texts in its celebratory version of the English triumph over the French, its depiction of the hero of Poitiers (the Black Prince) subverted expectations. Tussaud’s, one of the most popular visitor attractions in London, helped shape visions of medieval royals; their positive versions of royal characters such as Richard I can be contrasted with other more negative images of the king that circulated in nineteenth-century histories, literature and plays. Thus, in addition to illuminating the vital role technology played in shaping visitor experiences of the medieval, these three exhibits offer insight into the place of the medieval past in British lives and culture through their promotion of medieval characters and ‘significant’ events.

An analysis of the exhibits exposes their value in assessing the cultural work of the medieval past through comparisons with other pasts. Tussaud’s, which offered a wide range of historical and contemporary figures, illustrates shifting views of historical characters and periods through an analysis of figure placements, dressing and expression, guidebook descriptions and reviews. The Heraldic Exhibition showcases how emerging ideas about heritage and preservation influenced visions of the medieval past and approaches to medieval artefacts as something that needed to be preserved and conserved for future generations rather than revived (Gribling, 2017). For historians of nineteenth-century culture, this essay illustrates how exhibitions offer a valuable window into diverse and shifting attitudes towards the Anglo-Saxon and late medieval pasts, and the vital role of technology in shaping experiences of history. For museologists, it demonstrates how such exhibitions played with popular and scholarly narratives of the past, drawing on and reforming narratives found in art, literature and histories.

Acknowledgments

I would like to give special thanks to Louise Baker, archivist at Madame Tussaud’s, for access to the rich materials held in the archive. I would also like to thank Dr David Green, Dr Jennifer Tucker and the two anonymous reviewers for their comments on this paper.

Tags

Footnotes

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text