Power at play in paranormal history

The contested object biography of the Cottingley Fairy artefacts

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/242201

Abstract

This article presents a collective object biography and discussion of the Cottingley Fairy artefacts – cameras, photographs, watercolour sketches and print materials – held at the National Science and Media Museum. I demonstrate how the controversial paranormal claims made about the Cottingley cameras by Arthur Conan Doyle and Edward Gardner relied on the manipulation and obfuscation of key episodes in their history of use, a strategy that worked to distance the objects from each other and from their young female working-class operators Frances Griffiths and Elsie Wright. My article seeks to both interlink and restore the lost episodes in the histories of these objects as a way of redressing the power imbalance between the plebeian producers and elite cosmopolitan popularisers of the world-famous fairy photographs. I suggest how a new curatorial approach to the materials might reject the familiar – and largely inaccurate – narrative of deliberate hoax and deception still widely attached to the case, and instead use them to tell a new story about the technological experimentation, artistic aspirations and social restrictions experienced by working-class girls in early twentieth-century Britain.

Keywords

camera technology, Cottingley fairies, Edward Gardner, Elsie Wright, Frances Griffiths, Midg camera, object biography, photography, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, spirit photography

Introduction

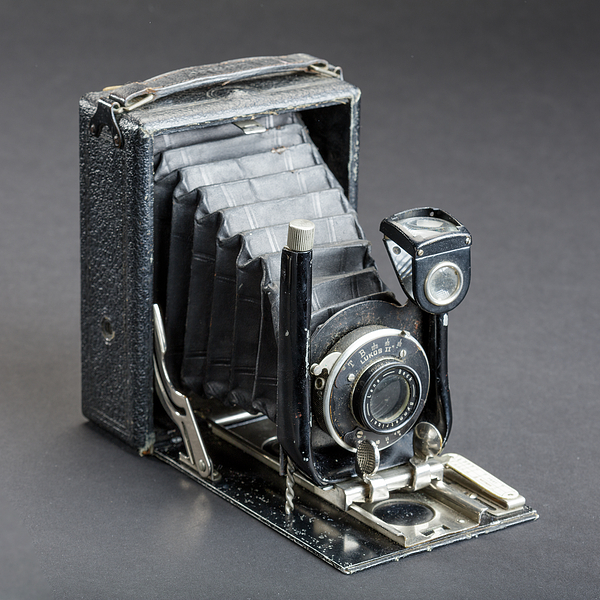

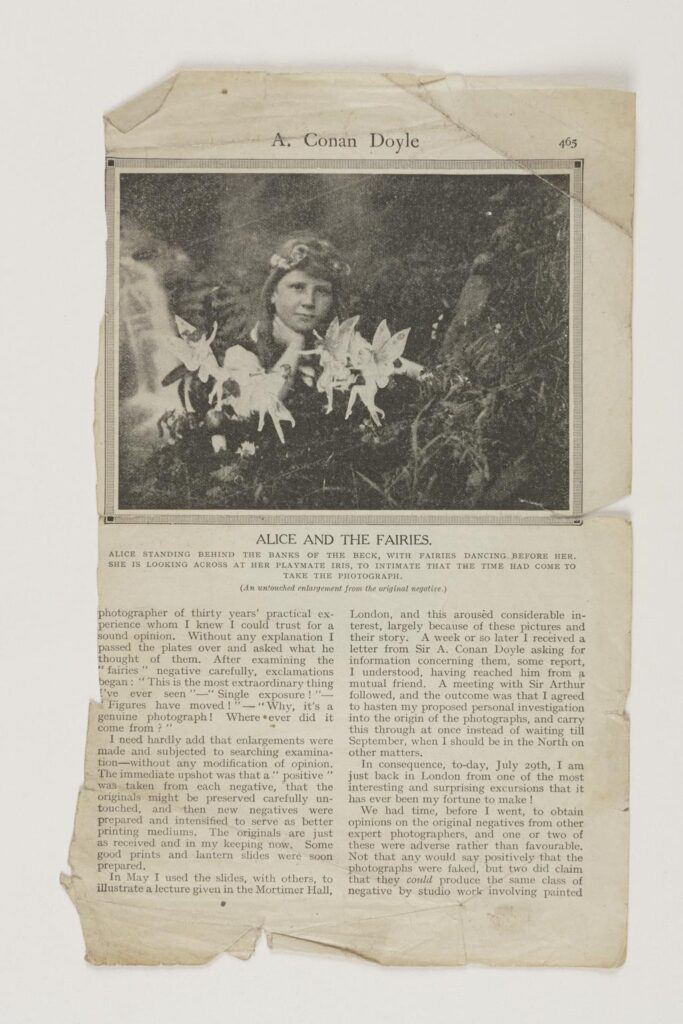

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/The National Science and Media Museum (NSMM) in Bradford is home to a collection of artefacts related to and responsible for one of the twentieth century’s best-known paranormal controversies: the case of the Cottingley Fairies. In 1917, the teenage Elsie Wright and her nine-year old cousin Frances Griffiths used a ‘Midg’ camera (Figure 1) to produce two trick photographs that appeared to show them interacting with fairies: ‘Alice and the Fairies’ (Figure 2) and ‘Iris and the Gnome’ (Figure 3).[1] First intended only as an internal family joke, the photographs became subjects of international curiosity, debate and derision when subsequently championed by British theosophist Edward Gardner and literary celebrity and ardent spiritualist Arthur Conan Doyle as evidence for the existence of supernatural beings and, accordingly, the truth of their own alternative spiritual beliefs.[2] In the summer of 1920, Doyle and Gardner gifted the girls with two new Cameo cameras (Figure 4 and Figure 5) and a substantial quantity of photographic plates with which they urged them to produce new images.

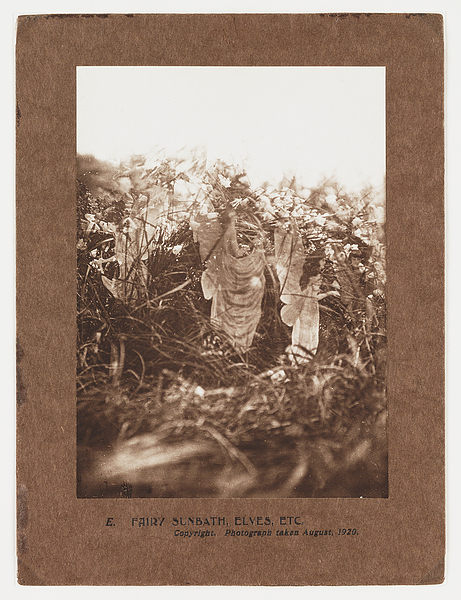

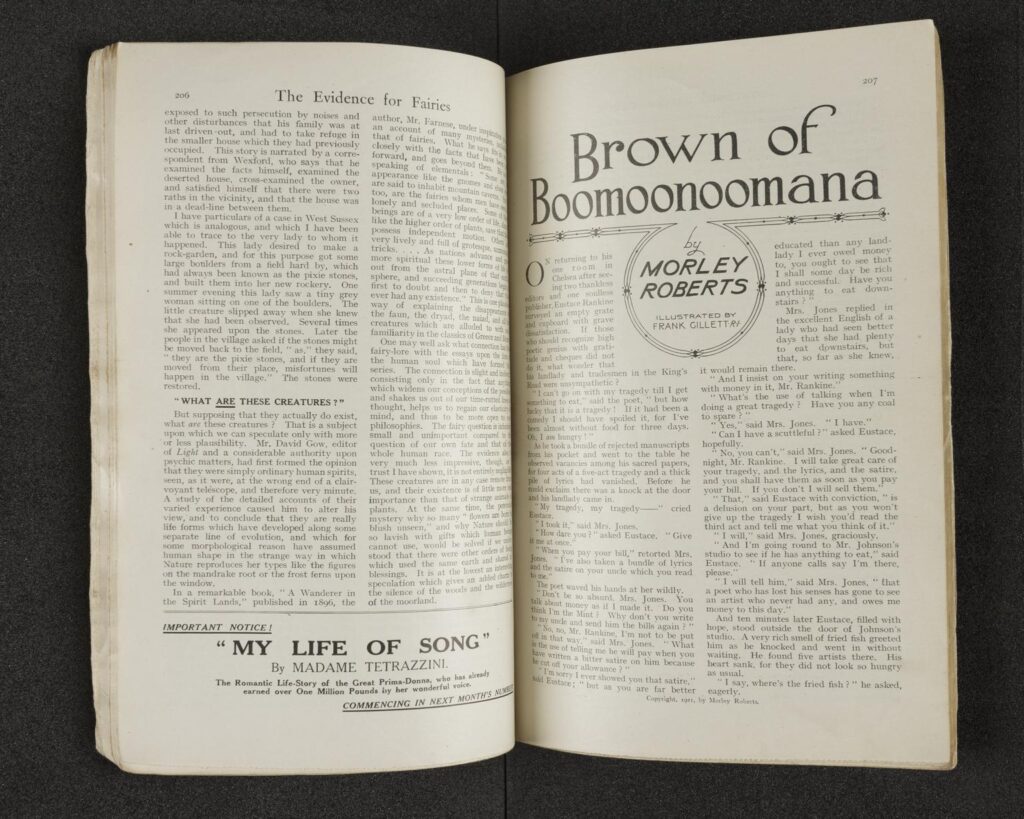

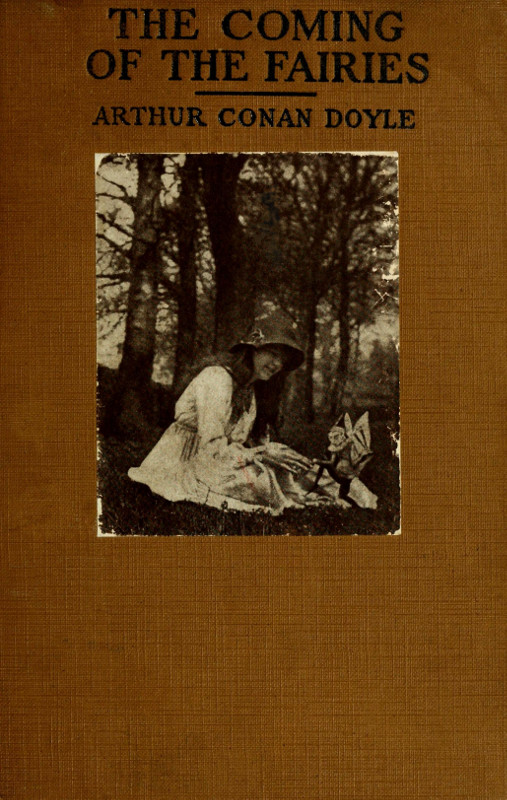

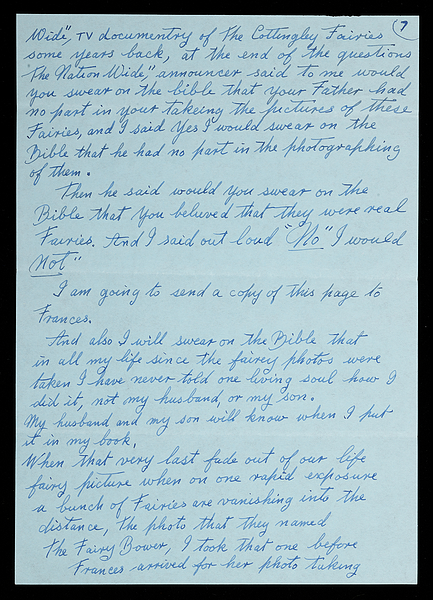

Pressured to satisfy the requests of these men of higher social rank than their own, Elsie and Frances created three additional photographs: ‘Alice and the Leaping Fairy’ (Figure 6), ‘A Fairy Offering Flowers to Iris’ (Figure 7) and ‘Fairy Sunbath, Elves, Etc’ (Figure 8). All five images formed the explosive centrepiece of the two articles that Conan Doyle then wrote about the fairies for the December 1920 (Figure 9) and March 1921 (Figure 10) issues of the Strand Magazine, and later expanded with the collaboration of Gardner into the book The Coming of the Fairies released by Hodder and Stoughton in 1922 (Conan Doyle, 1920; 1921; 1922). In the furore that followed, money was made, jobs were lost and reputations damaged. Only in the early 1980s, long after the deaths of Gardner and Conan Doyle, did Elsie and Frances go on record separately to explain how the images had been made.[3] In a 1983 letter (Figure 12) to the photography historian Geoffrey Crawley now held at NSMM, Elsie described the fairies as being entirely her own ‘jocular brain-child’ and having no basis in reality;[4] Frances, however, would contend in her posthumously-published Reflections on the Cottingley Fairies, written with the support of her daughter Christine, that while the first four images were indeed fake, she had seen real fairies many times while playing on her own down at Cottingley Beck, ones who bore little resemblance to the stereotypical images in the photographs (Griffiths, 2009, pp 16–19).

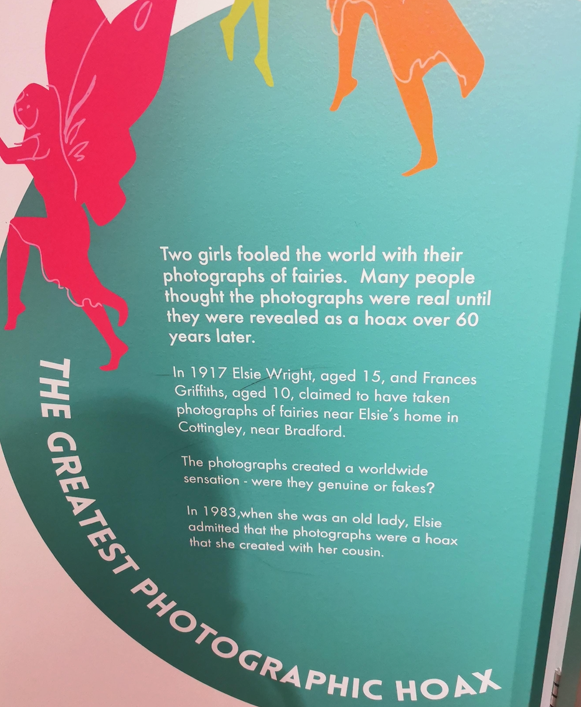

Until the NSMM’s temporary closure in July 2023, a selection of these materials was exhibited in the Museum’s Kodak Gallery, accompanied by an interpretive panel labelling the case ‘The Greatest Photographic Hoax’ (Figure 13). This provocative billing positioned Elsie and Frances as intentional tricksters who had cunningly ‘fooled the world’, as claimed in the accompanying interpretive panel text, deceiving high-profile men alternately imagined as naïve, gullible or, in Conan Doyle’s case, driven witless and desperate by grief.[5] Yet this framing is not consistent across the Cottingley collection records, where a conflicting and sometimes contradictory story is told about their entangled histories. The digital collection pages for the ‘Midg’ and Cameo cameras, for example, adopt a more playful and obfuscatory tone to explain their historical use. After describing how in the summer of 1917, Elsie and Frances ‘took a photograph that miraculously revealed the existence of fairies’, it observes that ‘a second photograph several months later…revealed a single winged gnome greeting Elsie Wright’ (‘Midg’ camera; quarter-plate ‘Cameo’ camera). Of the second phase of photographs taken in 1920, the online interpretive text states that they were only taken ‘after some difficulty’ due to the fairies ‘being shy and reluctant to appear’ (Ibid). A final explanatory paragraph then reveals the mundane means by which the images were created, allowing the records to reproduce within their own narrative structure the same dialectic of concealment and revelation used to frame the Cottingley case. It is claimed here that both Elsie and Frances later ‘maintained they had really seen the fairies’, although only the latter had done so.

These variations, however slight, speak to the larger tensions and sensitivities involved in interpreting objects with such a vexed, and even dramatically opposed, history of ontological interpretation by different actors, some elite and some working class, some male and some female, some sincere new religious believers and some co-opted or coerced participants in a cause about which they knew almost nothing. How should such objects be situated within the space of the science museum? To what extent, and how, should the magical claims once made about them be presented and preserved for diverse audiences? To whom should agency and authority be attributed in their object biographies? As with all collection materials, the history of the Cottingley objects is far too complex and rich to be contained within a single record or interpretive panel; decisions must be made about which assortment of details will best educate, impact and entertain museum users. Key among these considerations must be our ethical obligation to the different actors in the Cottingley case, figures whose presence within the extant object biographies of these artefacts continues to be shaped by their uneven access to social power and cultural prestige. In what follows, I will examine how prevalent narratives about Cottingley have been shaped by the minimisation, exaggeration or misrepresentation of the relationships between the humans and the artefacts central to the case; I will then suggest how new object biographies of the materials that the NSMM is uniquely equipped to create might redress power imbalances within their historiography and popular cultural representation.

The magical history of object biography

If we are to tell new stories about Cottingley, it is essential that we disenchant a particularly obdurate vein of object interpretation that developed around the case, one that, as cultivated by Gardner and Conan Doyle, both prioritised the magical agency of the technical instruments over that of Elsie and Frances and, in fact, imagined Elsie and Frances as magico-technical instruments who had produced the images without craft, volition or intention. Although undeniably heterodox in motivation, this narrative nonetheless anticipates what we might recognise as the always-already magical potential of the object biography as a mainstream interpretive practice and methodological technique within museum curation – although in the latter case, its aim has been to empower rather than suppress non-elite histories and actors. Formulated by Igor Kopytoff in his path-breaking 1986 essay ‘The Cultural Biography of Things’, the object biography is a critical practice that, in the words of Jody Joy:

provides a method to reveal relationships between people and object…by following object lives from birth life death. An object is produced, or “born”; it is involved in a particular set of relationships during its lifetime; it also “dies” when it is no longer involved in these relationships (Joy, 2009, p 540).

From its initial articulation within social anthropology, the object biography has migrated into many other disciplines, including archaeology, history, cultural studies, and museum and heritage studies, operating in the latter field to shed new light on collection materials by tracking their movement from production into use and then accession within ‘institutions and practices in the metropolitan centers’ (Alberti, 2005, p 560). As method, the object biography insists that no single phase in an object’s ‘career’ wholly fixes its meaning or eclipses all others.

The latter insight was crucial to the Media of Mediumship project (Figure 14) that I led in 2021/22 with Dr Efram Sera-Shriar and Dr Emma Merkling. MoM examined how late Victorian and early twentieth-century scientific instruments and communication technologies held in the collections of the SMG and Senate House Library[6] – the X-Ray, the telegraph, the photograph and the radio, for examples – were repurposed by occultists and sceptics to test, validate or debunk paranormal alleged phenomena. Although such uses may never have been mainstream or widely accepted, they remain important to the cultural history of such artefacts and thus deserving of attention within their object biographies. In calling attention, where possible, to such lesser known or unorthodox episodes in an artefact’s history of use, the object biography can exert considerable political force by refusing on principle to recognise or authorise only those functions linked to or endorsed by social elites. Although largely descriptive in method, the object biography has the potential to be a highly charged political tool; as Alfred Drazin observes, ‘[d]escription is not intellectually neutral; it is a purposeful act’ (Drazin, 2020, p 64).

We can observe this radical potential within a particularly fascinating, if under-recognised, occultural precedent for academic practices of object biography: psychometry. A common practice among nineteenth-century spiritualist mediums and theosophical clairvoyants alike, psychometry is a technique by which sensitive individuals handle specific objects – a handkerchief, perhaps, or a sealed letter or stone – and claim by visionary means to discern otherwise inaccessible aspects of their history. In his study of Anglo-American occult geographers William and Sarah Denton, whose book The Soul of Things (1863) interpreted fossils by psychometric means, Richard Fallon argues that psychometry allowed ‘practitioners on the fringes of elite science’ to ‘make bold if precarious claims, instilling individual agency and intuition into the inhuman abyss of deep time’ (Fallon, 2023, p 146). Although scientifically inaccurate, the work of psychometers such as the Dentons remains an important part of the history of scientific popularisation and of the attempts of non-elites to engage with and gain scientific authority. Furthermore, as Fallon explains, their technique was by no means wholly distinct from the more secular practices of contemporary ‘inanimate object biography’ from which it took inspiration, ones that saw palaeoscientific writers such as Edward Drinker Cope and Hugh Miller adopt vivid visionary language and supernatural figuration to animate the prehistoric past for popular science audiences (Fallon, 2023, pp 153, 146–7). In the instances which Fallon examines, psychometry functioned as a strategy by which common people could seek empowerment and equality. Yet, as we will see, the power dynamics of paranormal object biography have never been exclusively or necessarily democratic in tenor. In the case of Cottingley, as we will see, high-profile paranormal believers levied their authority to suppress and distort the testimony of working-class users about their relationship to the fairy cameras and photographs.

The affinity between scientific and heterodox practices of object biography persists to this day, if largely at a metaphorical level. Scholars have observed that the very idea that an object might have a form of personhood – that it might, like humans, possess ‘biographical possibilities’ (Kopytoff, 1986, p 67) or even agential power – resonates with animistic and magical understandings of the world. Janet Hoskins points out that the work of Alfred Gell in particular has fostered ‘an agentive turn’ in social anthropology that encourages us to recognise the agency of non-persons such as ‘spirits, machines, signs, and collective entities’ (Hoskins, 2012, p 74). In Gell’s words, this potential derives from their ability to ‘produce effects [and]…cause us to feel happy, angry, fearful or lustful’ (Gell qtd in Hoskins, 2012, p 76). We misunderstand such effects if we attribute them exclusively to an object’s creator or user; on the contrary, writes Chris Gosden, ‘things behave in ways which do not derive simply from human intentions…things have life cycles of their own’ (Gosden, 2005, p 195). The Cottingley case provides a sharp illustration of how objects may defy the intentions of their creators, purchasers and users; so too does it show how the deliberate suppression of key episodes within an object’s life history, and the misattribution of their effects to supernatural agency, worked to disempower some of their human associates.

The Cottingley cameras as instruments and testimony

I now want to consider the power dynamics at play with the secular and occult object biographies produced for, and imposed upon, the NSMM’s Cottingley Fairy artefacts. These fall largely into three classes: cameras; images (including copyright reproductions of the photographs and watercolour sketches of fairies painted by a young Elsie Wright); and texts (namely the Strand Magazine articles and book published by Conan Doyle, and the manuscript letter written by Elsie Hill to Geoffrey Crawley in 1983). Although deeply entwined, the lives of these objects have been unevenly recognised, assessed and authorised within popular narratives of the Cottingley case and its febrile techno-spiritualist milieu.

The quarter-plate ‘Midg’ camera that took the first two photographs belonged to Elsie’s father Arthur and was produced by W Butcher and Sons sometime between 1902–1917. Popular due to its relative affordability, portability and ease of operation, this model was a top seller in early twentieth-century Britain, participating in a wave of technological innovation that ‘democratized photography and placed it within reach of a “cultivated” working family’ such as the Wrights’ (Owen, 1994, p 64). It belonged to the hand-held class of cameras that had been introduced to the market some 30 years earlier (White, 1983, p 28), and was equipped with a built-in shutter and automatic magazine that facilitated an unprecedented level of speed and spontaneity in image capture. The automation of the magazine, describes Geoffrey Crawley, allowed ‘photographers to take a series of exposures…on plates of 12 or more without the necessity to interchange separate plate holders, remove the dark slide, take the exposure, replace the slide, take out the older, exchange it for another, and so on’ (Crawley, 1982b, p 1406). The two Cameo cameras subsequently gifted to the girls by Conan Doyle and Gardner were of the smaller, lighter and more portable folding type, features which, in addition to their equipment with a ‘special lens which cost £20’, made them considerably more expensive than the ‘Midg’ (Griffiths, 2009, p 54). These came accompanied with a substantial amount of costly marked plates, the exact number of which remains up for debate and may have been deliberately downplayed in The Coming of the Fairies in order to heighten the apparent success of the second photographic phase.[7] Presumably, the two men must have hoped that the superior and more agile cameras would allow the untutored naïfs they presented the girls to be to better capture the evanescent fairy forms; within the Wright family, Frances later recalled, these gifts instead incurred a pressing weight of obligation, a debt that had to be repaid. Conan Doyle’s involvement, she writes, made ‘Aunt Polly…persistent about taking more photographs and giving them better value of money’ (Griffiths, 2009, p 57). A greater attention to the value, both financial and social, of the cameras involved in the case disrupts the familiar narrative of hoaxer versus dupe, and instead positions Frances and Elsie as unwilling participants in an uneven exchange process over which they had little control.

The automatic mechanism of both box and folding camera styles not only increased the speed of photography, but also amplified opportunities to produce accidental or deliberate double exposure. This capacity was so well-known as to become part of the deliberate design of some early twentieth-century box camera models, where it was advertised as a unique selling point for buyers seeking to take fun family photographs. Thus this 1905 advertisement for the Butcher’s Craven Camera in The Amateur Photographer boasts:

The particular advantage of the No. 2 Craven Camera is that it is fitted with a patent Duplicator behind the Lens, by means of which the two halves of the plate may be exposed separately. This is useful for many things, but specially for taking Trick Photographs, such as a person wheeling himself in a wheel-barrow, or a man’s body on someone else’s legs, or any one object in two different positions in the same plate (‘Butcher’s Guinea Cameras’, 1905).

It was through such deliberate double-exposure that many contemporary sceptics believed Elsie and Frances had made the Cottingley photographs, although we now know that it featured only in the production of the fifth image – the fairies in the first four were hand-drawn by Elsie, then cut out and mounted on pins. Nonetheless, what this advertisement demonstrates is that practices of photographic trickery were far more widely practiced, easily accomplished and, indeed, celebrated as a form of harmless entertainment for photographic amateurs than either Conan Doyle or Gardner would be willing to countenance in The Coming of the Fairies.

The promised ease with which these cameras could be used would become a crucial battleground in the contentious debates that raged around the reality of the fairies. The girls took the initial photograph, ‘Alice and the Fairies’, on the first instance they were allowed to touch the ‘Midg’, using the single plate that Alfred, conscious of the cost, had given them. Frances recalls ‘making sure Elsie did everything exactly as father did when he took photographs’ (Griffiths, 2009, p 24), such as using the finder to judge the focus (Crawley, 1982b, p 1406). The Cameo cameras gifted by Gardner and Conan Doyle were ‘towards the simpler end of the available models’ (Crawley, 1983, 11), and thus easier to use again. Frances confirmed this facility in her recollection of how they took ‘Alice and the Leaping Fairy’: ‘it was…quite an easy snapshot to take with this much more sophisticated camera’, even considering that their ‘knowledge of photography was practically nil!’ (Griffiths, 2009, pp 54, 55). Conan Doyle must have been aware of this affordance; after all, he was himself an accomplished amateur photographer who had in the 1880s published 13 articles in the British Journal of Photography (Crawley, 1983b, p 117). Nonetheless, both he and Gardner worked in The Coming of the Fairies to emphasise instead the impossibility of the girls possessing either the skill or intention to use the cameras in this manner. For example, Conan Doyle there reproduces a letter he sent to fellow spiritualist Oliver Lodge, affirming that ‘we had certainly traced the pictures to two children of the artisan class, and…such photographic tricks would be entirely beyond them’ (Conan Doyle, 1922, p 18). Conan Doyle’s phrasing here minimises not only the capacity of the camera, whose skilful manipulation is deemed more difficult than it was, but also that of its operators who are both infantilisingly described here as children. As Nicola Bown has argued, this persistent and deliberate strategy of infantilisation was necessary to the men’s occultural interpretation of the case, an approach spearheaded by Gardner ‘in order to verify for himself that [Elsie] saw the fairies, for only a child could see them’ (Bown, 1996, p 67). In fact, Elsie Wright was almost or actually 19 at the time she took the picture in question and, like many girls of her class, had been out of school and working to support herself for years.[8] Later, The Coming of the Fairies would add a distinct cosmopolitan bias to this tactic of diminution, citing the view of Harold Snelling, the photographic professional who had examined and enhanced the negatives of the 1917 pictures, that ‘it was surely impossible that a little village with an amateur photographer could have the plant and the skill to turn out a fake which could not be detected by the best experts in London’ (Conan Doyle, 1922, p 32). Elsie and Frances were indeed relatively inexperienced camera users, but both the sophistication of the devices and their creativity rendered the images they produced perfectly achievable.

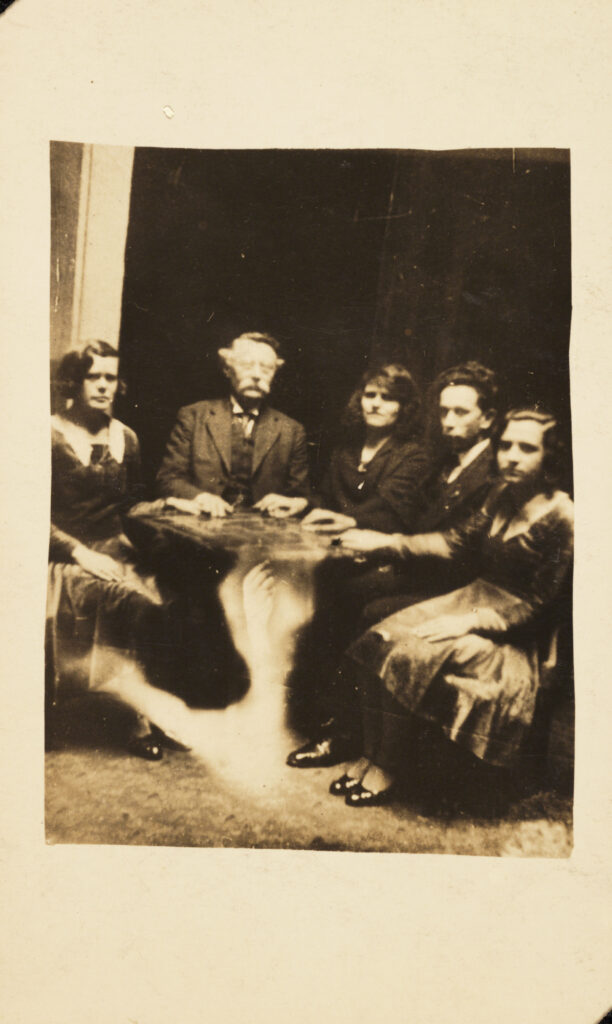

Conan Doyle’s and Gardner’s refusal to recognise these qualities represents their larger campaign to expunge Elsie and Frances qua makers and operators from the magical narrative of Cottingley in which they had each invested time, money and reputation. Neither man observed the photographs being taken, and of the two only Gardner travelled to Cottingley to meet the girls in person. Conan Doyle never made the trip. This reticence seems strange in light of his willingness to stake his name on what he boldly deemed ‘an epoch-making event’ in his first Strand article on the case (Conan Doyle, 1920, p 463). Furthermore, it represents a marked deviation from the usual empirical practice which Conan Doyle claimed for his own brand of scientistic spiritualism, one nowhere more evident than in his contemporary investigation of renowned spirit photographer William Hope whose remarkable Crewe-based spiritualist circle albums are also held in the NSMM collection (Figure 15). Conan Doyle became Hope’s champion after the photographic medium was accused of fraud by psychical researcher Harry Price in early 1922, when The Coming of the Fairies was in preparation. When the author visited Hope in Crewe in 1919, he had adopted a wholly different investigative procedure than he would with Cottingley, inserting himself directly into the image production process as observer, operator and sitter.

As he later describes in his book The Case for Spirit Photography, published only three months after The Coming of the Fairies, Conan Doyle brought a sealed package of his own photographic plates to his first meeting with Hope as proof against interference. The Case provides a blow-by-blow account of how the author opened the packet in Hope’s dark room, marked the plates with his own hand, and inserted them into the carrier of the medium’s by-then distinctly old-fashioned tripod camera. After Hope took the pictures, Conan Doyle developed them himself (Conan Doyle, 1923, p 21). Initial results being unsatisfactory, he tried again with one of Hope’s plates, taking, he insisted, ‘precautions which…would only weary the reader if I gave every point of detail’ (Conan Doyle, 1923, p 22). This time Hope was more successful, producing a photograph of Conan Doyle with the ‘spirit extra’ of a young man which, although ‘not a good likeness,’ had the appearance of his son Kingsley ‘as he was some eight years before his death’ (Conan Doyle, 1923, p 22). In addition to examining the plates, the carrier and the camera operation in this testimonial, Conan Doyle also scrutinised the photographer himself, making much of Hope’s 17-years’ experience of photographic mediumship and inspecting his hands and face for physiognomic indicators of honesty. ‘His forehead is high and indicates a good, if untrained, brain beneath,’ he writes. ‘The general effect of his face is aquiline with large, well-opened, honest blue eyes, and moustache which is shading from yellow to grey… His hands with their worn nails and square-ended fingers are those of the worker, and the least adapted to sleight-of-hand tricks of any I have seen’ (Conan Doyle, 1923, p 16). Here at least, human and photographic object are treated as mutually deserving of close, in-person scrutiny if they are to vindicate the spiritualist crusade.

In The Coming of the Fairies, by contrast, the story that Conan Doyle tells about paranormal photography is one in which the camera as dynamic instrument and working-class girls as its untutored but gifted operators have much less active presence. Perhaps he feared that the supernatural status he sought for the pictures would be compromised by too much attention to their technical production, in a way that he had not been while examining Hope. As an adult, Frances came to believe that the great man had stayed away from Cottingley for another reason – namely, that he privately suspected that the photographs were fake and did not want to be implicated in their eventual exposure. Until then, he would exploit their propagandistic value for spiritualism from afar. ‘Perhaps I’m a cynic,’ she writes in her memoir, ‘but much later on, when thinking over these events for the writing of this chronicle, I think Conan Doyle must have suspected that Elsie had painted cut-outs’ (Griffiths, 2009, p 63). Whatever the reasons, ones no doubt complex, Conan Doyle kept his distance, vaunting the evidentiary potential of the photographs from a distance rather than in proximity to their production.

Distant viewing: the Cottingley Fairy photographs

As opposed to the cameras, the fairy photographs and their negatives offered a distinctly safer, stabler and, for Conan Doyle and Gardner at least, financially lucrative form of paranormal material evidence; moreover, they had the considerable advantage of being available for scrutiny and manipulation at a distance.[9] The NSMM holds prints of all five photographs, bought at auction in 1998; as the copyright label on their frame mats suggests, these are not the original prints but rather reproductions made available for public sale on 10 January 1921 at the cost of 2 shillings 6d (Crawley, 1983b, p 92). In addition, the Museum holds a copy print of Elsie’s original ‘Alice and the Fairies’ which, as Geoffrey Crawley has shown, was considerably retouched by Harold Snelling prior to its publication in the December 1920 issue of The Strand. In Gardner’s words, this far more obscure original was ‘intensified’ prior to publication ‘so that the originals might be preserved carefully untouched’ and, apparently, at the direct behest of the family (Conan Doyle, 1922, p 33). Crawley casts considerable doubt on Gardner’s claims about the extent of, and rationale, for this enhancement, observing that:

his justification to Doyle that the Wrights in sending him the negatives had enclosed a note asking him to improve them and touch them up seems a little odd. After all, he had presumably, at that stage, only asked the Wrights if he could inspect the negatives – why should they enclose a note asking him to improve them? (Crawley, 1982b, p 1409)

Whatever his intentions – whether ingenuous, deceptive or even, in Nicola Bown’s psychoanalytic interpretation, a reflex of childhood trauma[10] – the effect of Gardner’s intervention was to sharpen the photographic evidence in the favour of this theosophical worldview and to give him further control and ownership over an image set for which he was now a kind of co-producer. Having obtained the negatives and, more significantly, their copyright from the Wright family, Gardner and Conan Doyle could now disseminate, manipulate, interpret and commodify the images entirely from the space of the metropole.

As purchasable commodities rather than family keepsakes, the Cottingley images entered a whole new, and fascinatingly diverse, career stage, one in which buyers could take them home as objects of wonder, decoration or as pieces of evidence with which they could engage in a form of mass participatory visual investigation. The profits from their sale went largely to the three men who had shaped their final form and secured their fame: Arthur Conan Doyle, Edward Gardner and Harold Snelling. Albert Wright had freely given rather than sold the rights to Conan Doyle and Gardner, refusing to take money for what he saw as simply a childish prank, albeit an inexplicable one; consequently, Snelling received a third of the retail price for each half-plate sold, and Conan Doyle and Gardner split the rest (Crawley, 1983b, p 92). ‘Doyle seems to have stuck out for his right to a larger share in any profits’, writes Crawley, ‘since, as he pointed out, the exercise really rested on the article in the Strand’ (Crawley, 1983b, p 93). While the willingness of the Wrights to forego any profits is offered in The Coming of the Fairies as proof of their innate honesty, and hence, of the credibility of the pictures (Conan Doyle, 1922, p 38), no reverse form of moral judgement seems to have been imposed on the men who happily profited from the work of Elsie and Frances. Instead, Gardner’s and Conan Doyle’s appropriation of the sales income seems to have passed unnoticed among the wider public, extending and entrenching the inequity, as Nicola Bown observes, of their uncompromising takeover of the meaning of the images (Bown, 1996, p 63).

In later life, both Frances and Elsie would come to deeply resent what they retrospectively recognised as a deeply unequal financial relationship with Conan Doyle and Gardner (Griffiths, 2009, p 67),[11] and their own attempts to redress this balance were never successful. In 1972, Elsie had in her own words ‘tried to put this longest ever practical joke of mine up for sale to world newspapers to ‘Sotherby’s’ [sic] in London, thinking of breaking the news after the sale to Frances along with a fat check’, but the auctioneers – who, to be fair, were probably not the right buyers for this confession – declined the sale on the basis that they only dealt with ‘very ancient documents’.[12] As young girls, Elsie and Frances had felt unable, and lacked opportunity, to tell their own stories; as adults, they could not to do so in a way that might bring them financial reward. After revealing the cut-up technique they had used to stage the first four pictures (Cooper, 1982, pp 2338–2340), Elsie and Frances each planned to publish their own separate and full memoirs of the case; sadly, they died before doing so. Their relationship to the products of their own labour had by this point become seemingly irreversibly estranged.

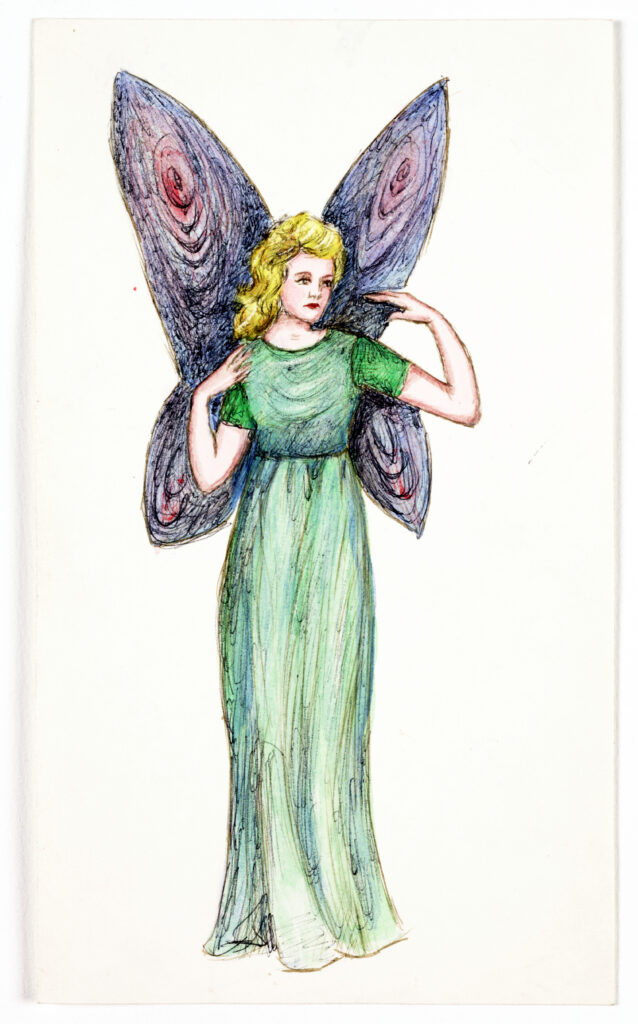

Cottingley beyond the camera: Elsie Wright’s watercolour sketches

We can now see how the Cottingley cameras and prints gained discreet and fluctuating forms of value – familial, spiritual, evidential and financial – across the course of their varied lives as commodities, personal possessions and, for Gardener and Conan Doyle, paranormal artefacts that could, if interpreted correctly, ‘jolt the material twentieth-century mind out of its heavy ruts in the mud, and make it admit that there is a glamour and a mystery to life’ (Conan Doyle, 1922, p 41). Far from enriching Elsie and Frances, these different types of capital were, as we have seen, sometimes accrued at their direct expense. This inequity was enabled through the expungement of another set of Cottingley artefacts, also now held in the NSMM collection, from The Coming of the Fairies’ supernaturalist interpretation of the case: namely, three watercolour sketches of fairies that Elsie Wright produced in her youth. These evidence the artistic skill that Conan Doyle and Gardner so desperately needed to deny her in order to put the pictures beyond suspicion. Acquired by the NSMM in 1998, these delicate paintings show a series of stylishly coiffured fairy women striking fashion poses in boldly coloured robes and wings, forming a sharp chromatic contrast with the better-known black and white hues of the five foundational photographs (Figure 16, Figure 17, Figure 18). They may be examples of, or based upon, the ‘drawings of mannequins in dresses of her own design, washed in water colours’ that Elsie, in Frances’s recollection, brought home ‘every night’ when she was working as an illustrator for a local jewellers in the late nineteen-teens (Griffiths, 2009, p 13); alternately, they may be examples of the ‘test’ sketches that Gardner, not in entirely good faith, asked Elsie to make in order to establish their inferiority to the allegedly ‘real’ fairies of the photographs (Conan Doyle, 1922, p 40).

The drawings capture the nascent artistic skill of a working-class girl whose inspiration owes more to the contemporary women’s pages than to some nostalgic Arcadian idyll, and one who, far being from stuck in a perennial state of childhood innocence, embraces the modern and the modish. Little wonder, then, that they were not reproduced in The Coming of the Fairies, and indeed they are only referred to briefly and somewhat contradictorily there. Conan Doyle and Gardner could not deny that Elsie had a history of drawing fairies – although they would minimise its extent – nor could they conceal the existence of her prior artistic and photographic experience. After all, it was well known that, in addition to her employment at the jewellers, she had also worked as a production assistant at the local Gunstons photography studio and done colouring work at Sharpe’s Christmas card factory (Crawley, 1982a, pp 1376–78). Instead, they disparaged her talent, claiming that her performance in Gardner’s test revealed that ‘while she could do landscapes, the fairy figures which she had attempted in imitation of those she had seen were entirely uninspired, and bore no possible resemblance to those in the photograph’ (Conan Doyle, 1922, p 40). The journalists who came to investigate the case following the first Strand article were only slightly less damning, with a reporter for the Westminster Gazette writing of Elsie in January 1921 that ‘as to whether she could have drawn the fairies when she was sixteen I am doubtful. Lately she has taken up water-colour drawing, and her work, which I carefully examined, does not reveal that ability in a marked degree, though she possesses a remarkable knowledge of colour for an untrained artist’ (qtd in Conan Doyle, 1922, p 47). What Conan Doyle would describe as a more ‘severe attack on the fairy pictures’ published in the Birmingham Weekly Post observes that Elsie ‘had been in the habit of drawing fairies for years, and…in addition to this has access to some of the most beautiful dales and valleys, where the imagination of a young person is easily quickened’ (Conan Doyle, 1922, p 55). Here we see an important dynamic that would continue to shape the reception of the objects for years: the watercolours and the photographs assume opposing roles in Cottingley’s collective object biography, with recognition of one coming at the expense of the other. The Post’s distrust of the photographs allows them to recognise at least the duration of, and multiple sources of inspiration for, Elsie’s fairy drawing output, while Gardner and Conan Doyle reduce the drawings to no more than a failed test.

As Geoffrey Crawley notes, this judgment, along with the publicity the men created around the case, had a devastating impact on Elsie’s burgeoning artistic career in more ways than one. First, she was fired from her job at Sharpe’s ‘because of the persistent callers for interviews and possibly her refusal to allow the use of one photograph on a Christmas card’ (Crawley, 1982a, p 1378); second, and more enduringly, their words rocked her confidence in ‘the one thing she had really wanted to do’ (Crawley, 1983d, p 334). Gardner’s and Conan Doyle’s hostile quarantining of Elsie’s sketches from the photographs represents a form of bias that is just as deserving of curatorial challenge as their supernaturalist interpretation of the images. Long kept separate, the drawn and photographic forms of Elsie’s fairy representation might be brought together, displayed as the entwined artistic experiments of a young, working-class female multi-media artist whose career was truncated by unsought sensation. Collectively, they demonstrate that the Cottingley pictures had a skilled if untaught creator whose goal was not mass-scale deception but rather self-expression.

The artist explains: Elsie Hill’s letter to Geoffrey Crawley

These expressive aspirations feature also in SMG object number 1998-5148/1–9, the nine-page handwritten letter that Elsie wrote to Geoffrey Crawley (under her married name of Hill) in 1983 to explain how and why the photographs had been made. It forms the collection’s most powerful rebuttal of both the supernaturalist and the hoax-based framings of the photographs. 81 years old at the time of its writing, Elsie here describes the ‘pickle’ in which she and Frances found themselves when the photographs became public, and the subsequent notoriety that made it impossible for them to come clean. Their silence, she explains, was neither gleeful nor triumphant, not the result of a subversive pleasure in hoaxing their social superiors, but rather a reflex of pity. ‘I was…feeling sad for Conan Doyle’, she writes, because:

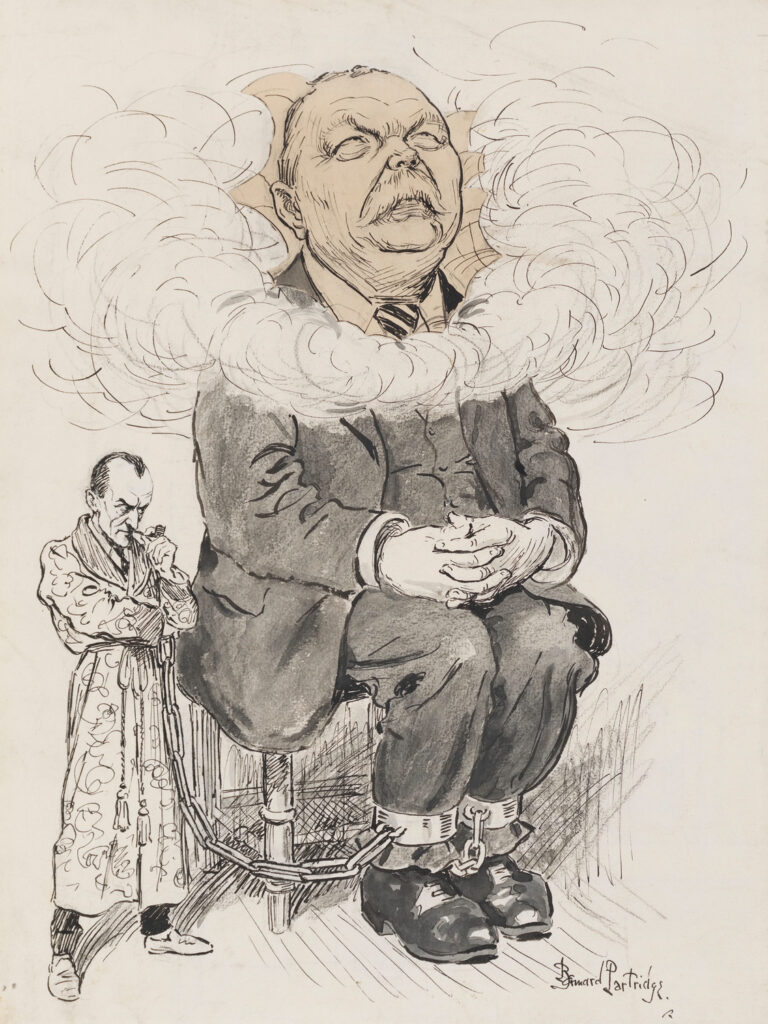

we had read in the newspapers of his getting some jarring comments, first about his interest in Spiritualism and now laughter about his belief in our fairies, there was also a crual [sic] cartoon of him in a news paper chained to a chair with his head in a cloud, and Sherlock Holmes stood beside him, he had himself recently lost his son in the war and the poor man was probably trying to comfort himself with unworldly things. So I said to Frances alright we won’t tell as Conan Doyle and Mr Gardener are the only two we have known of, who have believed in our fairy photos and they both must be at least 35 years old[er] than we are, so we will wait till they have both died of old age, then we will tell[13] (Figure 12).

Even after the men’s deaths, she writes, new hindrances appeared, such as Frances’s reluctance to disenchant her granddaughter. For too long, it seems, the time was simply not right for the photograph’s producers to reconnect with the pictures.

In addition to revealing her motives, the letter also testifies, in its small spelling errors and grammatical slips, to Elsie’s prematurely curtailed schooling, broken off at the age of only 13 when, like other working-class girls of her generation, she was expected to enter employment until ready for marriage. In this respect, the difference between her testimony and that of Conan Doyle could not be starker. While the venerated university-educated author had access to one of the most popular British monthly magazines in the land (and its copyeditors) for his far-fetched speculations about fairy existence, allowing him to create the buzz that would turn The Coming of the Fairies into a best-seller within a week of its release (Smith, 1991, p 391), Elsie Hill’s letter had little circulation and remains unpublished to this day. The testimonial focus of these texts also differs. While Elsie and Frances, as we have seen, are relatively side-lined in The Strand articles and The Coming of the Fairies, not interviewed at any length, observed in action, or recognised as viable camera operators, Conan Doyle and Gardner take central stage in Elsie’s letter as respectable men whose reputations must be protected at all costs, despite the chaos they introduced into the Wright household. Even if we suspect that Elsie here might be protesting too much here – surely it was not just the men’s repute, but also her own, that her silence protected – she displays a far greater sensitivity towards the interconnected social, familial and class stakes surrounding the photographs than the case’s foundational published texts. Perhaps this is because supernaturalist interpreters of the images like Conan Doyle and Gardner refused to recognise them as products of the social world at all, seeing them rather as spontaneous acheiropoietic manifestations projected straight from the numinous realm onto the photographic plate. In their handling, the Cottingley Fairy material artefacts – the cameras, plates, negatives and prints – are depersonalised, defamiliarized and decontextualised from their history of everyday use, imagined as pure techno-spiritualist instruments that seem almost to operate on their own, without need for any troublesome human interference.

Conclusion

Read collectively, the NSMM Cottingley Fairy artefacts reveal the ways in which new technologies can simultaneously empower and disempower their non-elite early adopters. The unsolicited fame achieved by Elsie Wright and Frances Griffiths in their girlhood was a deeply paradoxical one, granting them fleeting celebrity status as either otherworldly conduits or as obdurate liars – neither label, as we have seen, accurate – while also distancing and detaching them from the captivating images they produced. The story of how their humorous act of play resolved into a radically asynchronous power relationship is one that the NSMM’s Cottingley Fairy artefacts are collectively and uniquely equipped to tell. Elsie’s letter might form the basis for a creative audio collage, infused with street sounds and excerpts of popular music recordings from the 1920s, to be played within the Museum’s new Sound and Vision galleries and overlaid, perhaps, on a visual recreation of their original production in Cottingley Beck. Such a treatment would foreground the innovative modernity, rather than primitive archaism, of the images and position Wright and Hill, rather than Gardner and Doyle, firmly at the centre of the interpretive frame. The photographs, alongside Elsie’s watercolours, might be curated as innovative contributions to the history of British women’s photography, an emphasis that would foreground their intentionality and self-taught craft while countering the over-wrought infantilisation of their creators. At the very least, the curatorial materials and collection records might drop their verbal flirtation, however playful or metaphoric, with the paranormal interpretation of the images, not (or rather, not simply) because it has been disproven, but rather because it stifles and overrides the testimonies of their creators. As noted earlier, the object biography can be a powerful tool through which to challenge unequal social and epistemological hierarchies, but the recognition of an object’s autonomy – whether within the space of the Museum, or within psychometric performance – must not come at the cost of erasing the histories of its most marginalised human creators and users. Contemporary curatorial approaches can and should deliver to Elsie Hill and Frances Griffiths the complex agency elsewhere, and for too often, attributed to others in the case’s initial aftermath – to fairy beings, to Conan Doyle and Gardner as self-proclaimed discoverers of the images (Conan Doyle, 1922, p 14), or even to the ‘Midg’ and Cameo cameras themselves, imagined as operating beyond the ken or skill of their users. Focalised through the perspective of their users and makers rather than their elite alternative spiritual interpreters, the Cottingley artefacts have much to tell us about the technological artistry, ambitions and social aspirations of young working-class women in early twentieth-century Britain.

Acknowledgments

Research for this article was support by the Arts and Humanities Research Council [AH/V001140/1]. I thank the National Science and Media Museum and the National Library of Scotland for their assistance in accessing key collection materials.

Tags

Footnotes

Like so many other aspects of the Cottingley case, this account of the ‘discovery’ of the images by two disinterested and (hence) credible male witnesses has been manipulated to remove the agency and involvement of the Wright family. In fact, as Geoffrey Crawley recounts in his article series on the case for the British Journal of Photography, it was Elsie’s mother Polly who first alerted the theosophical community to the existence of the images upon attending a talk on Fairy Life at the Bradford Theosophical Hall in January 1920. 'After the talk', he writes, 'Mrs Wright was overheard to say that her daughter and a friend had taken photographs they claimed to show fairies. The lady lecturer asked to see prints and these were accordingly sent. She in turn sent these to Edward L. Gardner, a lecturer on the paranormal and a member of the Executive Committee of the Theosophical Society, who lived in Harlesden, London' (Crawley, 1982a, p 1376). Thus, while the Wrights certainly did not seek to financially capitalise on the photographs, it is not true that they were entirely aloof to their supernatural potential, nor was it the case, as Conan Doyle had claimed, that 'no attempt appears ever to have been made by the family to make these photographs public' (Conan Doyle, 1922, p 37). The fullest account of Gardner’s travels to Cottingley to meet Frances and Elsie and the gift to them of new cameras can be found in Crawley, 1982a, 1374–80. Back to text