Provocation: Journal experiments in overlay, data and provisionality

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/242205

Keywords

Digital publishing, Overlay journals

Introduction

The Science Museum Group Journal (SMGJ) has always been, across its ten years, a refereed and open access online journal free to publish and read. Being online rather than on paper always conferred potential benefits that we were keen to promote: the ability to feature very high-definition photographs, to draw on the Museum’s extensive image library, to embed sound and film files, to link elsewhere on the internet. It follows that, for much research – whether our own, or that of partners, or indeed for all publications on congenial subjects produced beyond our own practice – SMGJ is a good place to publish. A clear example is the special issue we produced to communicate the early concerns of researchers on the AHRC-funded Congruence Engine project: the combination of the capacity to publish very quickly – only a year into the project – whilst serving the funder’s Open Access requirement was ideal. Another example is the Material Cultures of Energy project special issue. Thus, we can say that over its ten-year life the Journal has been successful within the parameters that it originally set itself (to be a peer reviewed, open access, online journal able to surface the scholarship, practice and collections that are relevant to science museums everywhere). However, looking to the next ten years, this provocation argues that the Journal should do more.

What was in 2014 far from the norm has today become commonplace; many journals now have all these qualities. Times have moved on, and Open Access is now pervasive, indeed mandated by many of the funders of our research practice, including United Kingdom Research and Innovation (UKRI). And so, after ten years, the question arises of how we can seize the opportunities presented by new publication initiatives, demand for increased access to collections and stories, and the astonishing available variety of websites and web-resident techniques (including the tools of digital humanities and data science) to create something new. In particular, we should ask how an online journal might assist in making the collections of such museums more widely accessible, and how we may promote the varieties of research practice that enhance their use and understanding. This urgency arises from the serious underuse of the vast collections amassed for research use by our predecessors. And it is positively encouraged, by the very recent conclusion of the One Collection project that has seen the concentration of the vast majority of the Museum’s reserve collection in enviable environmental storage conditions in the Hawking Building at the Museum’s Science and Innovation Park near Swindon. Many other museums are currently moving collections away from urban centres to where land is cheaper;[1] universally this raises the issue of intellectual access.[2]

An overlay journal?

My first provocation is to advocate for the pertinency of the overlay journal model. To explain this, it is appropriate in this online context to refer to the Wikipedia page on the subject:

An overlay journal or overlay ejournal is a type of open access academic journal, almost always an online electronic journal (ejournal), that does not produce its own content, but selects from texts that are already freely available online. While many overlay journals derive their content from preprint servers, others…contain mainly papers published by commercial publishers, but with links to self-archived preprint or postprints when possible.[3]

What could SMGJ be like if we were to take the most creative and inventive definition of overlay journal, and what would it overlie? Formal papers at various stages of public exposure are the usual sources that overlay journals feed upon, but we are looking beyond this (Brown, 2010; Rousi and Laakso, 2024). One subject of discussion amongst staff of the Science Museum Group’s Research and Public History Department has been that we might go and consider the Museum’s assets as an effectively limitless lake of potential ‘content’ – to use that unlovely and widely used term. Above all, these assets should include the data representing the items in SMG’s collection. Object biography has been, since the first issue, one of our enduring formats, but this has remained at an editorial level as a decision to encourage scholarship on material culture. The Journal is not yet in digital conversation with the Collections Online data because that has proved technically difficult to achieve.[4] A full connection between the two makes sense in both directions: to find the context that gives the individual object record meaning, and to find the further exemplifications that reinforce an argument in the article’s historical account. We are not the only museum keen to enable such linkage; similar calls are being made in natural history museums.[5]

Two points are pertinent here: the second form of linkage (from context to objects) is technically difficult, though eminently achievable using techniques developed in the Congruence Engine project. These use entity linkage to connect items sharing the same terms in their metadata. Some of the wider potential here is visible in the decision of JSTOR to combine with its image service Artstor, which has the result that searches for texts also return images of objects in collections (including a selection from SMG) (Long et al, 2026; Anon, 2024). The second point is that we have always been clear that the Journal is not an in-house report but a place for research relating to science museums globally, and so focusing on our collection might seem to militate against that preference. But in the world of the internet, and even more so in the Linked Open Data version of it foreseen in the Towards a National Collection projects, a version of the SMGJ overlying the SMG collection would not have to do so in an exclusive manner: articles would be able to draw on collections data wherever it is held. At first this might have to be achieved by ‘hand-stitching’ hyperlinks, but if linkage of object types via Wikidata takes off, then it will be possible both to automate and to open-out access to similar objects across collections (Long et al, 2026).

In addition, SMGJ as an overlay journal might also overlie its library and third-party archive collections, and also the vast repositories of the Museum’s publications and the registry of its historical and administrative papers. Thinking about this material, most of which exists in highly heterogeneous and often delightfully intractable analogue formats, has been bread and butter to the small team that has begun to populate the SMG Open Access repository, hosted by the British Library as a service to Independent Research Organisations. Our approach here has been to think maximally about what a repository could be, including ‘grey matter’ related to past exhibitions and projects, for example, in addition to the minimal requirement of providing a home for close-to-publication versions of texts otherwise behind publishers’ paywalls so as to honour the terms of ‘green’ open access.

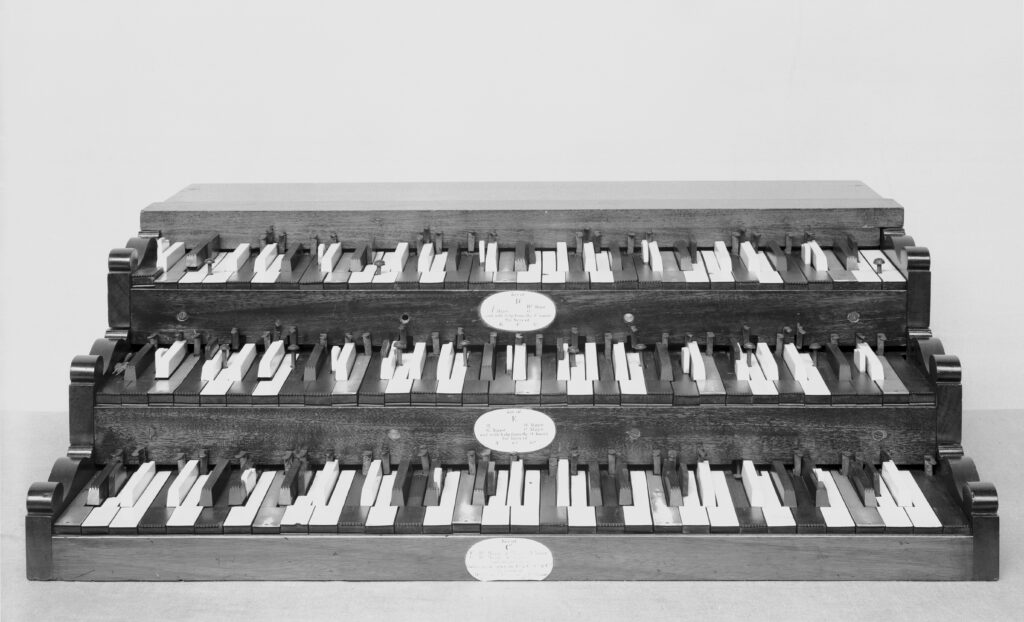

The experiment I propose to conduct and to publish here next year is to pretend that SMGJ is already a journal overlying the assets held by the Museum. My means to achieve this will be to draw on two resources already available online: SMG’s Collection Online and the repository. The subject of my experiment will be the development of the Museum’s collections concerned with sound and music, and especially with the research practice we have developed during the life so far of the Research & Public History Department as a signature subject of concern, which we have made the subject of a Repository collection. One purpose here would be to honour our Journal’s consistent aim to include accounts of museum practice, and for several reasons: because articulation engenders reflexivity and improvement in practice; to help colleagues in the universities to understand heritage sector organisations better; and for the sake of the historical record of what we have done – which can be surprisingly difficult to reconstruct after the event. I intend to explore this subject under three headings: a brief outline account of the development of SMG’s sounding collections; the path-dependent development of sonic research within the R&PH Department; spreading sonic research practice. As I say, music has been one strand of our activity on behalf of the Museum, and the example of the course of its exploration can provide a template for how we move on to investigate the themes of the research ‘clusters of excellence’ – including space and digital – foreshadowed in our Research Action Plan.[6]

Publishing data and documents

The second provocation I would like to make also arises from the Journal’s occupancy of the internet, namely linkage to many kinds of data. The Journal of Digital History, for example, incorporates a data layer. More widely, we are beginning to see in online journals the capacity to skip from footnote to the cited item itself (although this is constrained by your organisation’s subscriptions).[7] The recognition this implies – that sophisticated research publications in truth sit reflexively in multi-dimensional networks of reference – is dizzying: a universe of fractal rabbit holes for the incautious scholar to disappear into! The Journal could be a place that exemplifies this world of clickable connectedness between considered interpretations, documents and data relating to museum object records; an invitation for scholars to dive in.

More pertinently, combining this more general argument for reference linkage with the more specific example of a Repository overlay as discussed above, we could imagine the deliberate Repository publication of rare archive material as a valuable adjunct to the Journal publication of interpretive research. A specific case in point might be to make the Science Museum’s Annual Reports, which date back to its foundation and which are always a recourse in historical writing on this place, available on the Repository. These could be directly linked in historical publications on the Museum’s history, thereby creating a flexible resource for the curious, or indeed for pedagogical purposes in teaching Museum Studies, Science Communication, and History of Science.

Furthermore, as we have discovered in the Heritage Connector (Kalyan and Stack, 2021) and Congruence Engine (Boon and Rose, 2026) projects, research projects create data, datasets and website-resident digital projects with shelf-lives limited by the endless updating of browsers and other web technologies. In the case of Congruence Engine, for example, these might be dehydrated datasets, held in CSV files, that contain project-cleaned data associating machines in museum collections with geolocated historic building records Whereas the repository would be the home for the CSV file, a repository-linked online Journal article could provide long term preservation of the rationale and look-and-feel of comparatively short life online outputs derived from the data in the files.

Experiments in provisionality

The third provocation I would like to make is to propose a departure from the publication model of the ‘once forever’ article, which is the nearly universal format of academic publishing.[8] We normally expect a paper to have reached a level of perfection at the point of publication. Occasionally an author may revisit a successful book and produce a second edition, but this does not tend to occur with essay-length efforts. But, in truth, most papers represent a staging point in extended work in progress. Mike Heffernan of the Nottingham geography department introduced me to a good joke about this; he said, ‘a paper is a paper, but three papers is “a body of work”’! And I would argue that it is only the path-dependent form of the printed paper that prevents a single article from being ‘unknitted’ and extended into a new form. Online digital publishing, just as it eases the correcting of errors (as compared with paper journals) could readily provide the facility to reopen an argument and its empirical substrate by, perhaps, editing and reuploading. This would be a kind of provisionality that would enable the updating of a descriptive account such as the one I propose above. In that particular case, SMG has a continuing commitment to sonic research and public programming; the new permanent galleries at our National Museum of Science and Media are on the theme of ‘sound and vision’, for example, and Time Loops, an AHRC funded project will provide a ‘museum concert’ to mark the reopening of that museum. After a few more such projects, it would make sense to reopen the review article, not just to list more activity, but to take the opportunity to reflect on how it alters how we think about our work in that area.

Conclusion

In the world of digital possibility created in the online sphere, under the conditions of Open Access (which is itself moving from an obligation to an affordance), we would miss a major opportunity if we were to stick to our guns, solely reproducing established publication forms. There exists an imperative to seize the opportunities of our time so as to communicate museum research, and about research, ever more effectively. The suggestions I make here are those that occur to me now, but the field of possibility and opportunity is open. I commend these examples – a creative manifestation of overlay journal attuned to the needs of our parent organisation and to its communities of use, substantially better representation of underlying data and a relaxation of the boundaries of permanence of published work – to our community in the hope of lively discussion to follow.