The Whitworth: a place for Industry and Art

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/211604

Abstract

The Whitworth has been making art useful since 1889. Originally founded in the memory of the pioneering engineer Sir Joseph Whitworth (1803–87), the gallery was built for ‘the perpetual gratification of the people of Manchester’. As the Whitworth celebrated its 130th year, the gallery hosted a major exhibition which explicitly explores and acknowledges the history of the Whitworth institute, gallery and park.

A proponent of standardisation, Sir Joseph revolutionised precision engineering through his development of interchangeable parts in machinery. While he maintained a natural interest in technical education throughout his life, less is known about whether this support extended to the fine and decorative arts. Conversely, today the Whitworth is celebrated for its internationally significant collections of art and design and its contemporary exhibitions programme, but for many visitors the gallery’s association with the great Victorian mechanical engineer is less clear.

This paper, which was presented at the Science Museum Group Research Conference 2019: The Place of Industry, reflects on research that was first carried out in preparation for the exhibition ‘Standardisation and Deviation: the Whitworth Story’ (14 December 2019–January 2022). It is not intended to be an original piece of research nor to provide a comprehensive history of the gallery. What follows is a reflection on some of the original source material and research papers that were consulted in preparation for curating the exhibition. Together they have been used to illustrate how the history of the Whitworth provides an object lesson in how art and technology unite.

Keywords

Arte Útil, Arts and Crafts Movement, Great Exhibition, Manchester, Social Change, Useful Museum, Whitworth

The Whitworth: a place for Industry and Art

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/211604/002In 2019, the University of Manchester launched an ambitious vision to help ensure the city is a leader in the fourth industrial revolution,[1] in the same way that it was a pioneer for the first phase of industrialisation. But in 1883, just six years before the Whitworth was founded, the author and well-known critic of industrial capitalism John Ruskin wrote a rather damning account of Britain’s first industrial city. In his introduction to two papers, ‘Study of Beauty’ and ‘Art in Large Towns’, written by his friend and fellow art reformer T C Horsfall, he implored the founder of the Manchester Art Museum to ‘pour the dew of his artistic benevolence on less recusant ground’ (Ruskin, 1883). Manchester had become ‘the first model of unfettered industrial capitalism’ (Woodson-Boulton, 2007) and for Ruskin, the cost of industrialisation to humanity was too high.

Founded in 1889 with the stated intention to be ‘a permanent influence of the highest character in the directions of Commercial and Technical Instruction’,[2] the development of the Whitworth, its collections and practice demonstrates a unification of art and industry. From its inception, the collections at the Whitworth reflect many ways of making, and show how new technologies have often been used alongside historical and cultural traditions, offering new opportunities to re-evaluate and re-interpret conventional narratives about the relationship between art and industry.

The gallery was originally established from the wealth of Stockport-born engineer Sir Joseph Whitworth (1803–87), an individual from humble beginnings who made his fortune through his aptitude for engineering. Sir Joseph (see Figure 1) is perhaps best known for perfecting existing designs rather than for his original inventions and today his name remains synonymous for his introduction of the universal system of screw threads.

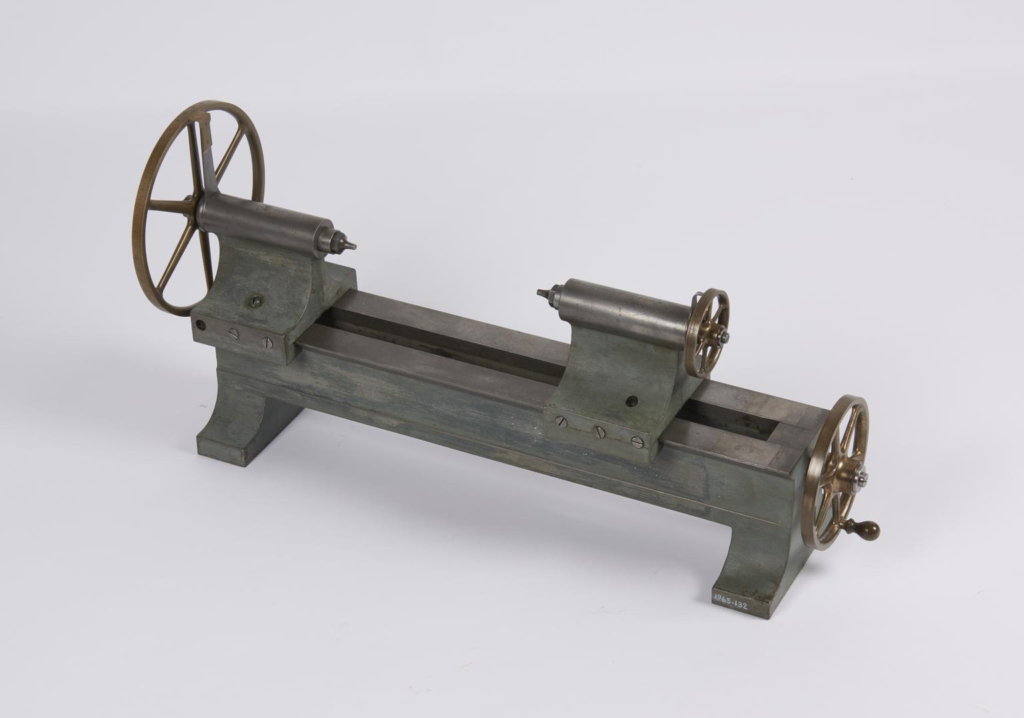

Whitworth transformed machine production through his introduction of standard, fixed scale gauges. Before this system, machine parts were not interchangeable as there was no way of ensuring that they were exactly the same size. He pioneered the development of uniformity in industry; reducing costs and improving efficiency.[3] During the Great Exhibition of 1851, the innovative engineer demonstrated his bench micrometer (see Figure 2). Capable of detecting differences of less than one millionth of an inch, his machine earned him international fame and helped pave the way for mass production.

Although Sir Joseph was meticulous, with a passion for accuracy in all areas of his working life, he provided no formal instructions on how the bulk of his £1,277,000 fortune (equivalent to over £169 million in 2019[4]) should be used after his death in 1887. This decision was left instead to his three trustees: his widow Lady Mary Louisa and his good friends and fellow philanthropists Robert Darbishire and Richard Copley Christie.[5] As James Moore writes, ‘this decision placed Whitworth’s legatees in a very powerful position to influence the future development of art and technical education policy in Manchester’ (Moore, 2018).

When looking at the history of the Whitworth, it is important also to consider broader concepts of art and industry in the nineteenth century. As Kate Nichols and Rebecca Wade point out in their introduction to Art Versus Industry?, ‘there has long been a seemingly non-negotiable opposition between “culture” and “industry”’(Nichols, Wade and Williams, 2016). They add, ‘Nineteenth-century art and industry continue to seem natural opponents because British culture has habitually…identified the Victorians with industrialisation, and nineteenth century industrialisation with largely negative connotations’(Ibid, p 5).

Much, for example, has been written about the role of the international exhibitions in the display of artistic and industrial objects, but as Nichols and Wade maintain, ‘In many cases art at international exhibitions has been written about independently of the industrial objects that surrounded it’ (Ibid, p 8). They argue that whereas historians such as Paul Greenhalgh have tended to separate the two, that the presence of the ‘fine arts’ at the Great Exhibition prevented it from becoming a ‘mere’ trade fair (Ibid).

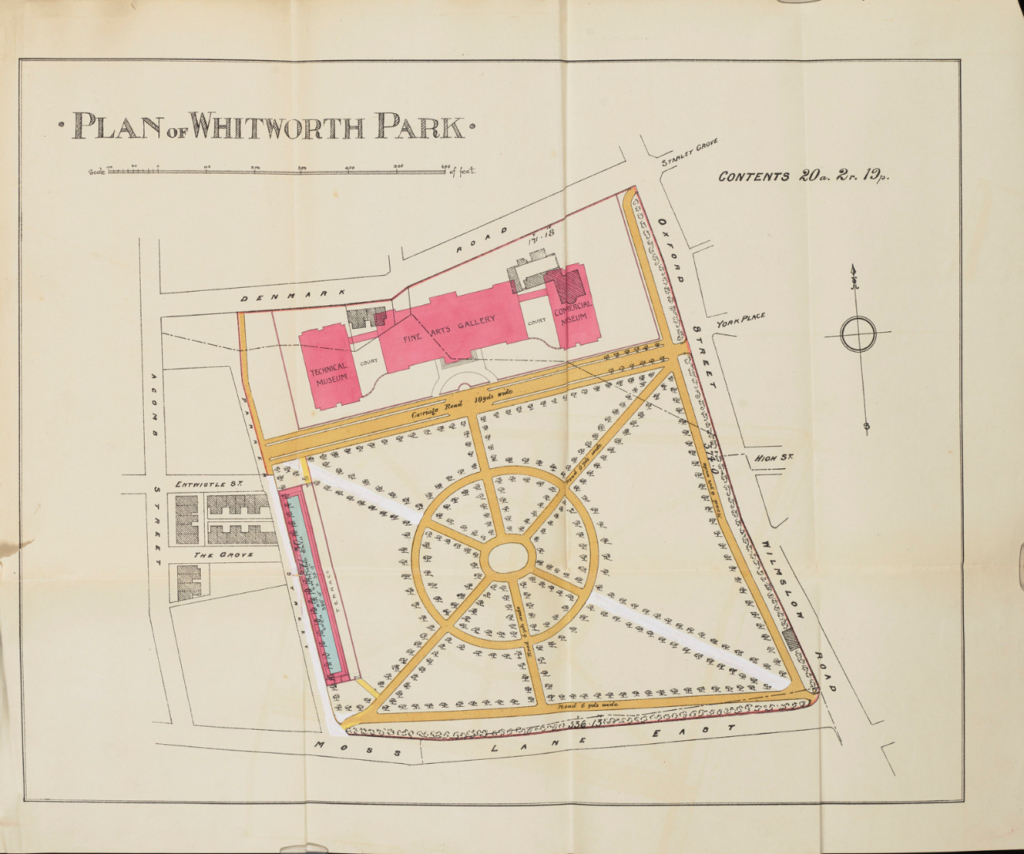

The Manchester Royal Jubilee Exhibition of 1887, which was a celebration of art, science and industry, serves to further support this argument (see Figure 3). The idea of creating ‘a grand International Exhibition’ in order to fund a permanent institution housing a ‘nucleus of a collection formed by a portion of its exhibits’ (Nugent, 2003) had been proposed as early as 1881 by the Manchester industrialist Ellis Lever. The main organiser of the Jubilee Exhibition was Sir Joseph Lee who suggested that it include a section devoted to the fine arts. A partner in the textile manufacturers Tootal Broadhurst Lee and Co, Lee went on later to become chairman of the Whitworth Institute (later known as the Whitworth Art Gallery). The Fine Arts section of the Exhibition received particular praise for its inclusion of watercolours with one critic calling for a permanent ‘representative Exhibition of English Water-colour painting from its crude beginnings…up to the present time. This branch of art has long been looked on as peculiarly English’ (Ibid).

By 1887, Manchester’s technical school was both in debt and inadequate in size. Alongside a lecture hall and library, the new ‘Museum of arts and industries’ was planned to hold departments for fine art, industrial art, mechanical, chemical and textile, commercial, raw products and samples. The Whitworth Institute, as it became known, was formally inaugurated in the summer of 1890. The Guarantors of the Royal Jubilee Exhibition transferred £40,000 from its profits to the Institute with the agreement that £10,000 be used to found a School of Art, £20,000 for the purchase of works of art and the remaining funds set aside to establish a School of Technology (Ibid).

After the introduction of new legislation in 1892, which passed responsibility for technical education to the municipal corporations, plans focused instead on developing a gallery of fine art and illustrations of ‘Mechanical and Industrial Arts and Manufactured Products’ (see Figure 4). Referring to Joseph Whitworth’s conviction that ‘mental culture should accompany manual proficiency’ (Moore, 2018), the industrialist William Mather, writing of the Whitworth, maintained that ‘the Institute was not mainly intended to benefit the affluent classes’ (Ibid). This is a principle that continues to underpin the gallery’s practice.

From its infancy, the ambition of the Whitworth’s founders and supporters was to build a forward-thinking art and design collection, combining technical instruction and inspiration. The gallery has actively sought to embrace the opportunities that the convergence of art and industry can offer, from the relationships forged with its early industrial benefactors to innovative partnerships between contemporary artists and scientists. This union is perhaps most evident in the evolution of the gallery’s distinctive collecting policy which at first reacted to the ‘commercial’ trends that had dominated the municipal galleries (Ibid, p 222). The founders chose to focus on textiles and the importance of watercolour in the history of British art – areas that they felt other public galleries had neglected in favour of (more fashionable) oil painting.

The early Jubilee Fund enabled the galley to purchase a total of 54 watercolours which included works by J M W Turner, William Henry Hunt, David Roberts, David Cox, Samuel Prout and Peter de Wint. In 1892, the Institute received what is still seen as a cornerstone of its fine art collection. Owner of the Manchester Guardian newspaper, John Edward Taylor, gifted 154 watercolours and drawings. Out of the 18 watercolours by J M W Turner, 11 were chosen from his early career.

Charting individual artists’ stylistic developments and innovation, and the emergence of the British landscape tradition, the group shows a strong instructive purpose. This educational role continued with the addition of prints to the collection, culminating in the transfer of the University of Manchester’s History of Art Department teaching collection in 1960.

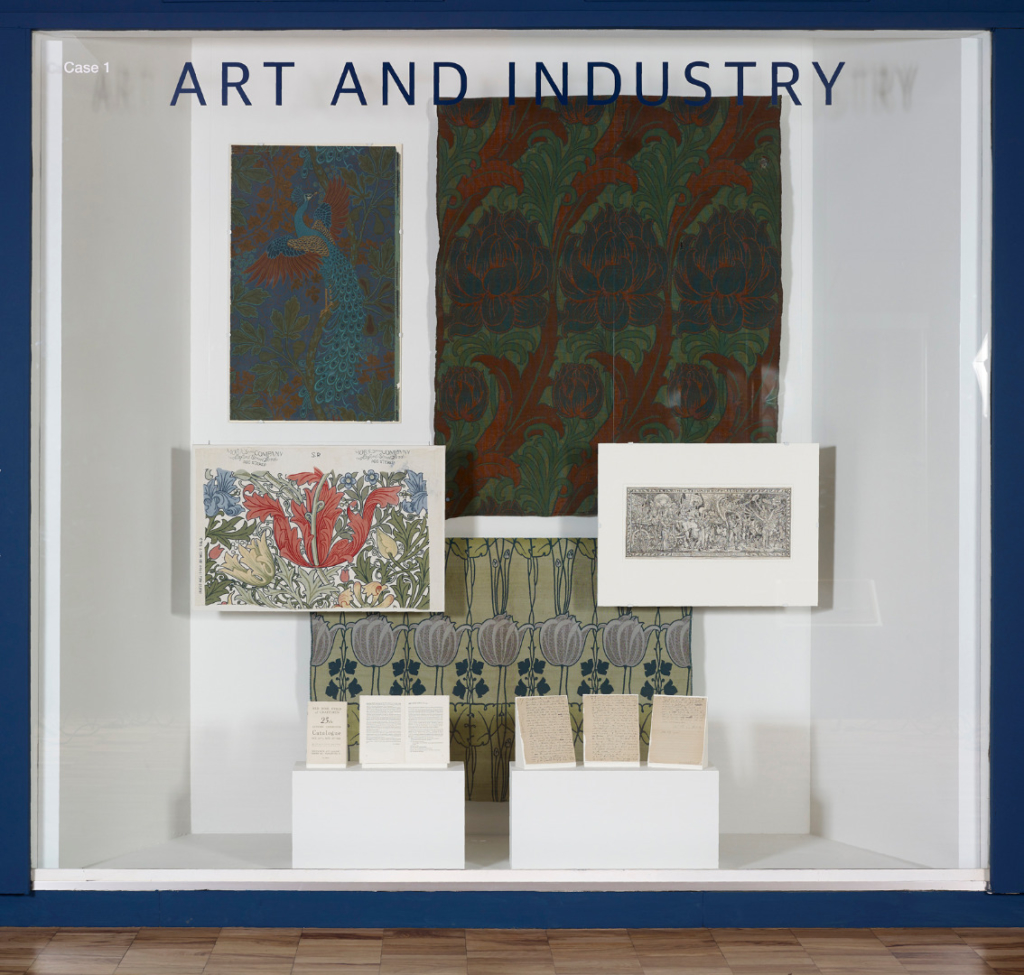

Today, the Whitworth’s Textile Collection is the largest and most comprehensive outside London, making it second in importance only to the V&A. As an integral part of a gallery which was intended as a museum of the industrial arts, this collection demonstrates how the Whitworth has stayed faithful to its original mission. Textiles made Manchester’s fortune and have been instrumental in shaping the city’s cultural capital. The Whitworth’s founders felt that designers and manufacturers in the textile industry should have access to the very best examples from across the world in their city’s own collections. The Textile collection includes some of the finest examples from the Arts and Crafts Movement and other design reformers. Acquired during its founding year, ‘Flora’ and ‘Pomona’ by William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones are two such pieces that reflect the gallery’s policy of contemporary collecting that continues today.

From the twentieth century, collecting of textiles extended to include industrial design. Today, material innovation sits alongside textiles that respond to social change and those that demonstrate technological excellence. As expanded by Maria Balshaw (former Director of the Whitworth), ‘This is entirely fitting for us as part of the University of Manchester, where material science is one of the leading research areas. We enjoy a productive and unique relationship with scientific colleagues there, as well as providing a resource for its students’ (Harris, 2015).

As with its Textile collection, the addition of wallpaper to the Whitworth’s collections reflects a further bridging of the divide between art and industry. The North West pioneered the mechanisation of the wallpaper industry and rapidly became a centre for production. Between 1899 to the mid 1960s the Wall Paper Manufacturers Limited, which had controlled around 98 per cent of the wallpaper industry, donated nearly 3,000 examples of wallpaper, providing a record of industrial achievement in the sector. Handprinted examples made for the elite seventeenth century market as well as some of the most enduring designs from the Arts and Crafts Movement sit alongside samples of industrial production for mass-market consumption (see Figure 8). As with textiles, the Whitworth has also developed a collection specialism in wallpapers designed by modern and contemporary artists that further cements the relationship of the wallpapers to the fine art collection.

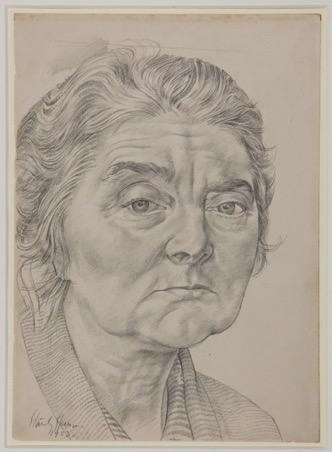

Alongside its progressive collecting policy, the Whitworth has continued to attract the support of influential figures and thinkers. A key individual in the Whitworth’s story is Margaret Pilkington (see Figure 9), whose industrialist family had co-founded the Pilkington Glass Works and Pilkington Lancastrian Pottery and Tile Company. Pilkington acted as honorary director from 1936 until 1959 at a time when the gallery was in severe financial difficulty. A talented wood-engraver in her own right, papers from her personal archive provide a valuable insight into the arts and crafts in the first half of the twentieth century. Having studied at the Slade School of Art and Central School of Arts and Crafts, Pilkington was the leading figure in the North West’s Red Rose Guild of Designer Craftsmen.[6]

In 1940, the Guild, which shared Arts and Crafts ideologies, moved to the Whitworth. The objectives of the Guild were to raise the standards of artwork and further the interests of artworkers and the community through the interchange of ideas. In his editorial for the Guild’s quarterly magazine, Crafts, Harry Norris wrote: ‘A craftsman is a man who makes things and has chosen to follow a different line of development from the industrialists. He is one deeply interested in the quality of the things he makes, and in addition, is concerned about the character and quality of the activity producing the work and its effect on the workman’ (Norris, 1942). This quotation shows the polemic that continues to exist between art and industry where industry is defined solely by commercialism, capitalism or economics and is distinct from quality. Yet, an underlying need to widen the accessibility of their products meant that within the Arts and Crafts Movement attitudes towards industry and commerce were not always clearly defined. As Jennifer Harris suggests in her essay that accompanied the exhibition William Morris Revisited, Questioning the Legacy (held at the Whitworth in 1996), despite growing support from designers who saw mechanisation both as a manufacturing necessity and a craft tool, ‘Industry today continues to be constrained by the artificial boundaries which have grown up between craft and design in the 20th century’ (Harris, 1996). Harris then argues for the continuing relevance of David Pye’s The Nature and Art of Workmanship (1968) in which he insisted on the complementary nature of the crafts and manufacturing industry:

economics alone will never justify their [the crafts’] continuation. The crafts ought to provide the salt – and the pepper – to make the visible environment more palatable when nearly all of it will have been made by the workmanship of certainty. Let us have nothing to do with the idea that crafts, regardless of what they make, are in some way superior to the workmanship of certainty, or a means of protest against it. That is paranoia. The crafts ought to be a complement to industry (Ibid, p 48).

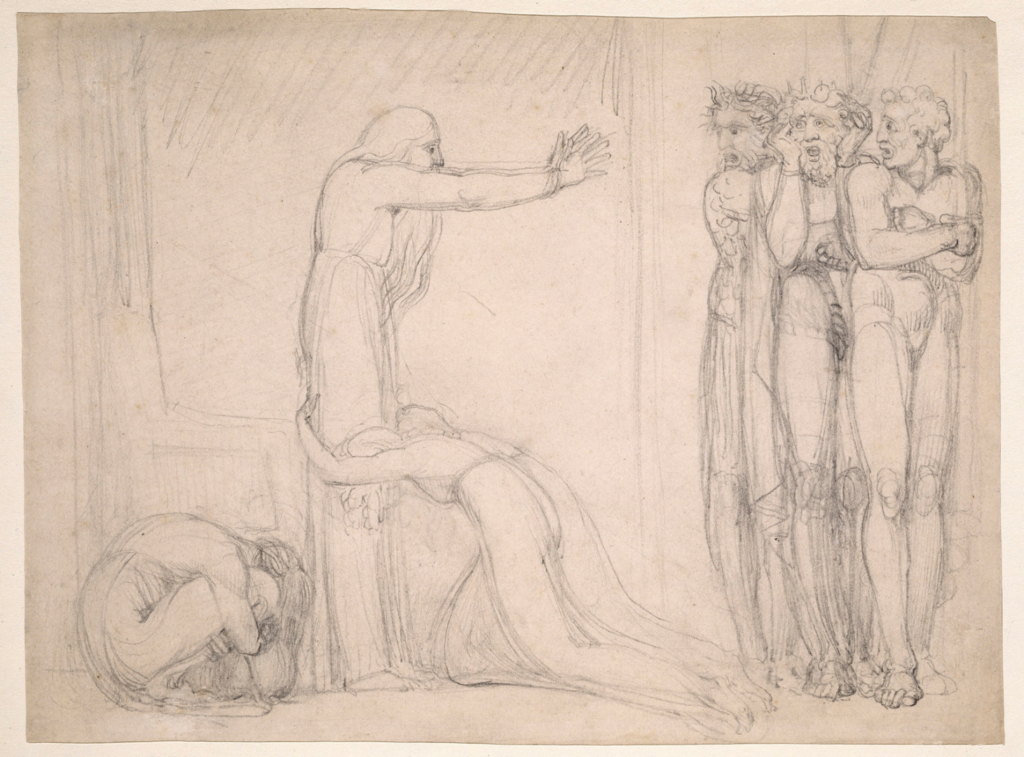

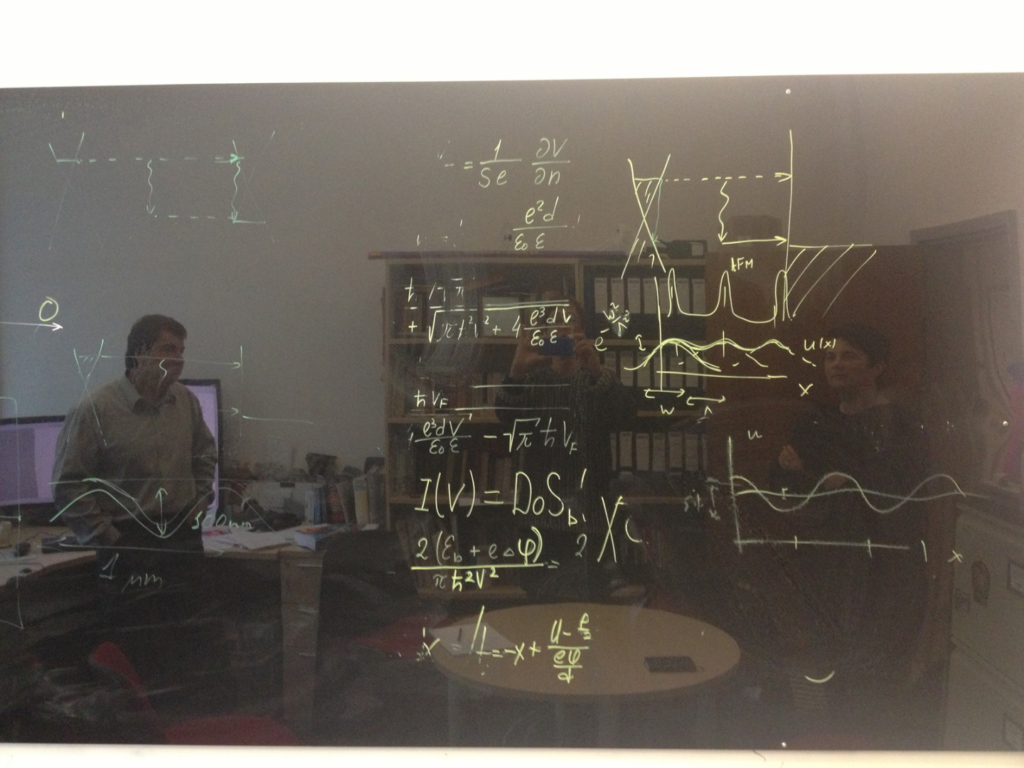

As a university gallery, the Whitworth has developed a continuing pattern of art and innovation through collaboration. The contemporary artist Cornelia Parker, prior to her solo show after the gallery’s redevelopment in 2015, worked closely with scientists at the University of Manchester, most notably Kostya Novoselov who, with Andre Geim, was awarded the Nobel Prize for the discovery of graphene – the world’s thinnest and strongest material. Working with gallery staff, Novoselov took microscopic samples of graphite from drawings in the Whitworth’s collection of drawings by William Blake, J M W Turner, John Constable and Pablo Picasso, as well as a pencil-written letter by Sir Ernest Rutherford, the father of nuclear physics (see Figure 10). He then made graphene from these samples, one of which Parker made into a work of art to mark the re-opening of the gallery after its redevelopment in 2015 (see Figure 11). A Blake-graphene sensor, activated by the physicist’s breath, set off a firework display which returned iron meteorite into the Manchester sky. This meteor shower marked a spectacular and unmissable opening to the new Whitworth.

After 131 years the Whitworth continues to explore further opportunities to close the historical divide that has existed between art and industry and to create a new narrative in its history through the new exhibition Standardisation and Deviation: the Whitworth Story (see Figures 12 and 13). For the very first time examples of Sir Joseph’s world-changing mechanical innovations have been displayed alongside highlights from its eclectic collections within the gallery that continues to bear his name.

Standardisation is woven throughout the exhibition to tell the history of the gallery and the development of its diverse and internationally significant collections. Alongside this, the exhibition demonstrates how the gallery has often deviated from standard models of practice, from its early collecting policies to its new vision; one that promotes the idea of the ’Useful Museum’[7] and art as a tool for social change and education.

The founding intention of the gallery is continuing to inform our conversations about the history of the Whitworth, its collections and its purpose today. We aim to transform the way that art is used and experienced by using it as a tool to open up conversation, generate empathy and actively address what matters most in people’s lives – here and now. By utilising the display of Whitworth’s machines as a proposal for creative engineering and the bringing together of art and science to affect technology, creativity and social change, we hope to inspire a re-thinking of the past and present purpose of the Whitworth.