Tinkering with nature: craft, domesticity and female labour in F Percy Smith’s ‘Data’ notebooks (1925–1944)

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/232009

Abstract

This article examines two notebooks belonging to the scientific filmmaker F Percy Smith, labelled ‘Data A’ and ‘Data B’, which are held at the National Science and Media Museum (NSMM) in Bradford. These notebooks offer valuable insights into Smith’s working process in the last two decades of his life – between 1925 and 1945 – and they detail the wide array of materials, tools and equipment that he used to produce his films. The article suggests some of Smith’s uses for the notebooks, such as noting down locations for collecting specimens or describing how to construct tanks and troughs for filming individual organisms. Using a wide range of supplementary sources, including images, videos and an interactive map, I argue that Smith’s work amounted to a form of scientific ‘craft’, which blended across his experimentation with photographic media and scientific observation. Dismantling the long-held belief that F Percy Smith worked entirely alone, the article uses the notebooks as an opportunity to highlight for the first time the role that two women played in Smith’s studio-laboratory: his wife, Kate Smith, and his assistant, Phyllis Bolté. The notebooks are a key source for understanding the production of natural history films of the interwar period, including the popular Secrets of Nature (1922–1933) series. The article reflects on what media scholars can learn from taking a closer look at the materials and methods used for making films of this kind.

Keywords

cinema, craft, domestic, F Percy Smith, filmmaking, Kate Smith, materiality, media, natural history film, Phyllis Bolté, popular science, scientific film

Introduction

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/A list of ‘odd materials’ from a notebook belonging to the filmmaker F Percy Smith includes the following items: ‘Kieselguhr (for diatoms), Micro objects jar, Thin sheet vulcanite, Asbestos, Mica, Pastilles, Natural wool, Feathers chicken, Roots, Thyme, Fish Moss, Cleared Horse Manure.’ Smith’s two notebooks, labelled ‘Data A’ and ‘Data B’, are kept in the Charles Urban collection at the National Science and Media Museum (NSMM), Bradford. They record in painstaking detail the day-to-day activities of Smith’s studio-laboratory, including a dizzying array of gadgets, makeshift devices and machines, all of which were used to capture the intimate lives of plants and animals on film. Often lauded as a ‘magician’ (Paul, 1931) or a ‘genius’ (Anon, 1945a), F Percy Smith’s popular science films, which showed the growth of plants in time-lapse and the microscopic life of tiny organisms, radically transformed the British public’s perception of the natural world, laying the foundation for modern-day nature documentaries (Gaycken, 2015, p 54–89; Boon, 2008; McKernan, 2015; Hovanec, 2019, Castro, 2019). This article builds on previous work by science and media historians who have explored how modern communications technologies were incorporated into the public culture of science (Nall, 2019; Hall, 2021; Greene, 2020), and offers a glimpse of the practices which lay behind some of Britain’s earliest and most recognisable natural history films.

Tim Boon argues that the innovations of scientist-cinematographers like F Percy Smith were characterised by a process of ‘tinkering’ that combined amateur knowledge in natural history with photographic expertise (Boon, 2008, pp 22–3). As this article will show, the ‘Data’ notebooks allow us to observe Smith’s ‘tinkering’ in action. While scholarship on Smith has often focused on his earliest work, placing him firmly in the context of Edwardian silent cinema, the ‘Data’ notebooks vividly illustrate Smith’s ‘tinkering’ as a constant and ongoing process, covering the period from his first work for the Secrets of Nature series (1922–1933) right up until his death in 1945. Thanks to these notebooks, we can track changes in the ways that science films were made in this period, including the shifting demands of producers and the growing influence of science consultants.

The notebooks permit a fascinating glimpse into Smith’s various contraptions and working methods, offering a rich and textured picture of the production of natural history from the perspective of material culture (Daston, 2004; Craciun and Schaffer, 2016; Werrett, 2015; Galison, 1997; Law, 2010). By helping to reconstruct the everyday aspects of F Percy Smith’s studio-laboratory, the notebooks also enable us to challenge some assumptions about how the filmmaker worked. Combining evidence from the notebooks with new research into the lives of his wife Kate Smith and his assistant Phyllis Bolté, this article casts doubt on the image of F Percy Smith as a lone genius. By seeing the notebooks as a laboratory guide or handbook, we can instead think of the Smith studio-laboratory as a site of close collaboration and experimentation, involving the input of at least three different people. The notebooks lay bare how the domestic and professional became indistinguishably blurred in the Smith household, the spaces and objects of the couple’s everyday life intermingling seamlessly with those of the laboratory. Even as academic science increasingly detached itself from the domestic space, popular natural history of the kind made by Smith and his assistants was often still conceived and crafted in the home environment (Jones, 2016; Carpenter, 2021).

The fact that Kate Smith and Phyllis Bolté’s involvement in Smith’s films has so far received close to no discussion in the literature is in part a reflection of the greater significance that scholars have placed on the formal analysis of films, which has been to the detriment of the materials, processes and individuals involved in their production. As historians of science and media begin to pay closer attention to the diverse conditions of production underlying popular mass media in the past, they are likely to uncover new insights that go beyond the formal analysis of their chosen artefacts.[1] In this article, the role played by female labour in Smith’s filmmaking is one such insight; the extent to which ‘natural conditions’ were artificially recreated in his studio-laboratory is another.

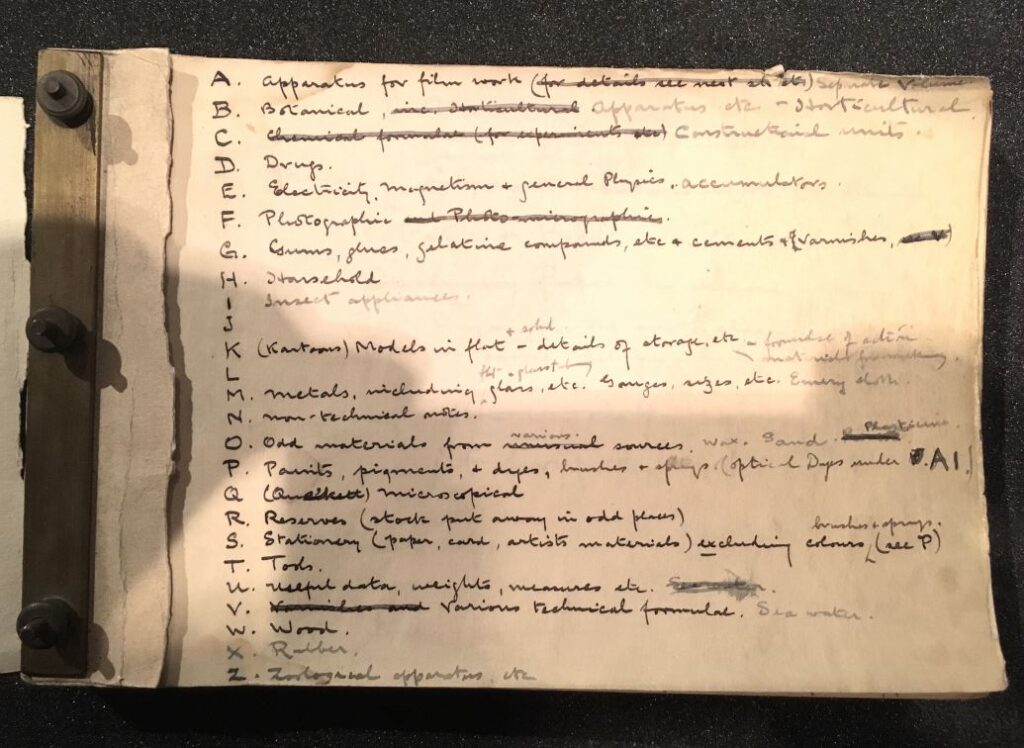

Description and main uses

The ‘Data’ notebooks consist of individual sheets of thick rectangular paper, bound with a firm brass mechanism.[2] The first notebook has a canvas cover with the word ‘DATA’ printed on a small sticker, while the second has a ripped title page that reads ‘DATA Vol. I’, although it is otherwise referred to in the notes as ‘Data B’. Each book begins with a detailed index (see Figure 1). From this we can tell that the notebooks were originally one single volume, as ‘Data B’ has an index of items from A–Z, while ‘Data A’ represents the expansion of item A, ‘Apparatus for film work’, which is itself sub-divided into sections, labelled AA to AZ. ‘Data A’ includes notes mostly about filming equipment, including cameras, lighting, lenses, mounts and microscopes, and different set-ups for each of these; ‘Data B’ lists more miscellaneous items, including sections on ‘Drugs’, ‘Insect appliances’, ‘Household’, ‘Stationery’, ‘Tools’ and ‘Rubber’. The handwriting is clean and legible. However, there are numerous crossings-out where Smith has worked out a more suitable solution to a problem: these notebooks therefore appear to have been produced partly as a manual or guide to Smith’s working methods, with new additions incorporated on the hoof.

Often Smith dated these additions and corrections, and thanks to this information we know that the notebooks were in use roughly between 1925 (the earliest recorded date) and 1944, a year before his death. New information was added throughout the 1930s, and he appears to have made considerable changes in the early 1940s: these will be discussed in detail later. Most of the entries are written in black ink, although there are some additions in pencil, and all appear to have been written by the same person. The ‘Data’ notebooks are the only detailed notes on Smith’s filmmaking techniques that survive. One other notebook from his archive, labelled ‘Cinematograph Work’, is a diary listing material shot between 1908 and 1910, with very little technical information. Smith apparently tried to dispose of this diary, but it was saved from the trash by his wife Kate (Tharp, 1941).

By 1925, Percy Smith had been making films for over fifteen years. A lifelong naturalist, his career as a cinematographer began while he was working as a clerk at the Board of Education in the 1900s. In 1908, he released his first film as part of Charles Urban’s Urban Science series, and he continued to work for Urban throughout the 1910s. During the First World War, he made animated war maps for the army, and later produced films for the navy. We know very little about Smith’s activities during the period immediately after the First World War, which one journalist called ‘the bleakest time of his life’ (Wilson, 1945). He continued to make some films for Charles Urban, but the latter’s fortunes began to turn. By 1917 Urban had closed his British business and returned to the US, and by the early 1920s he faced bankruptcy (McKernan, 2015). In 1923, Smith stopped making films for Urban, occupying himself instead with making animation films, including a series called Archie the Ant (Tharp, 1941).[3] Most of Smith’s scientific filmmaking contraptions, however, reportedly lay unused for several years, ‘shrouded in covers’ (Woollcombe, 1936). Luckily, in 1922 a producer named H Bruce Woolfe had begun to make a series of natural history films called Secrets of Nature, and hearing of Smith’s work was keen to add him to the team, which he joined in 1925. The earliest notes in the ‘Data’ notebooks, therefore, coincide with the time that he began working for the Secrets of Nature series (Hovanec, 2019; Castro, 2019; Long, 2020).

Why then, did Smith begin to keep detailed notes around 1925? The pressures of having to produce a steady output of material, coupled with the oversight of his producers at British Instructional Films (BIF), might provide part of the answer. Working for BIF, Smith was busier than ever, and this may have forced him to plan his work more carefully. Films with time-lapse footage or showing the life-cycle of a plant or animal over an extended period of time, moreover, could take months or years to film, and this meant that multiple films were usually being shot simultaneously, adding to the need for detailed note-keeping.

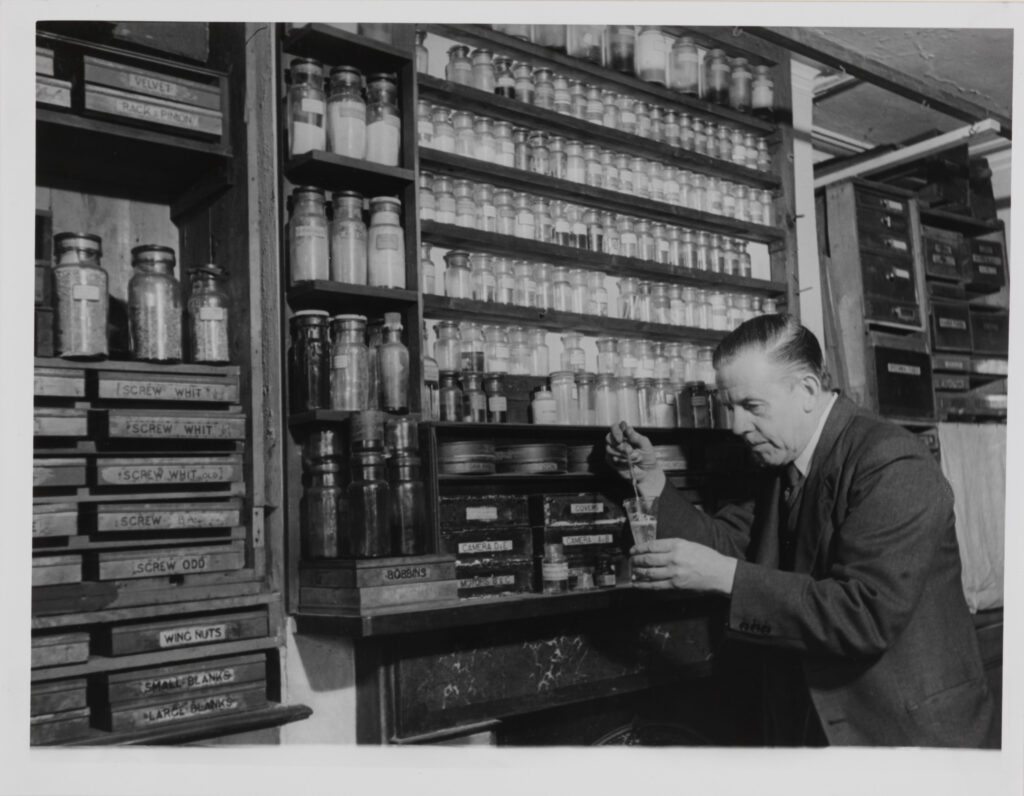

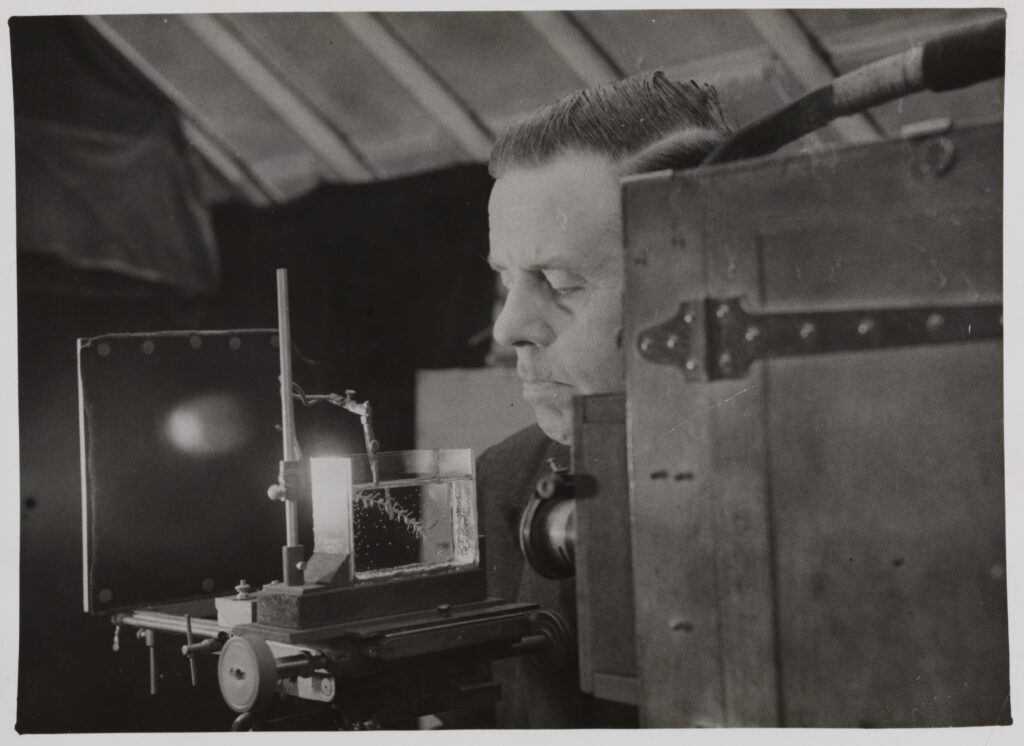

The notes show how Smith closely tracked the location of individual pieces of equipment, with labels for individual rooms, cupboards and drawers. In a laboratory as multifaceted as Smith’s, keeping close tabs on his equipment was clearly of immense importance. Although the notebooks contain no visual sketch of these locations, reading through them gives a rich impression of the spatial dimension of Smith’s working environment. Figure 2, a picture taken inside Smith’s laboratory, clearly shows how the notebooks matched onto a highly organised (if also idiosyncratic) system with individually labelled shelves and drawers. By the mid-1930s, the house on Chase Road in Southgate that Smith used as his laboratory had become so overcrowded that he and his wife moved their living quarters to a new home around the corner at 10, Charter Way. However, the notebooks suggest that parts of the laboratory followed them to their new home, with several items listed as being stored at Charter Way, including different types of rubber sheet which were kept in the couple’s bedroom, in an ‘old brown record case’.

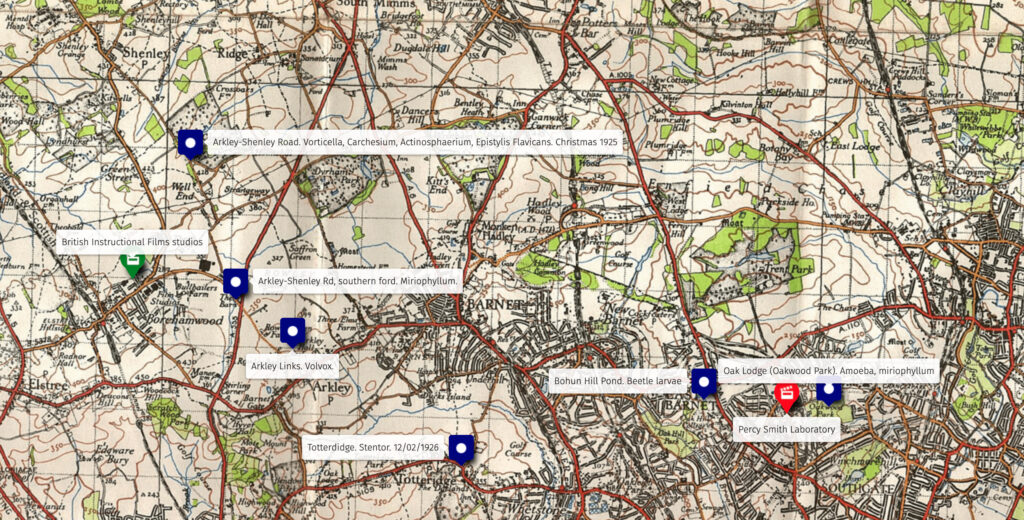

Click here for full screen interactive map

Smith collected specimens of microscopic organisms from local ponds and fields, keeping notes of the best locations for sourcing individual organisms. Figure 3, an interactive map, shows the different locations mentioned in the notebooks, and the specimens collected at each site. For instance, he collected Amoeba and Myriophyllum (water milfoil) from Oak Lodge, a large plot of land opposite his house. According to H Bruce Woolfe, ‘Smith got permission to go into the park whenever he liked to search the pond for specimens for his microscope, and he would spend days groping about in the mud and water for material for his specimen boxes’.[4] When the Smiths moved to Southgate in 1910, it would still have seemed like a semi-rural location, with one journalist who visited them in 1930 describing it as ‘on the fringe of the open country’ (Anon, 1930b). This meant that Smith could collect most of his specimens in the immediate vicinity. However, increasing urbanisation may have impacted the diversity of organisms available locally, and the notebooks show him visiting a wide range of locations across North London to collect specimens. Thus, we learn that on 23 November 1925, he collected Dileptus, a ciliate algae, from a sphagnum pond in Epping Forest. One of Smith’s favourite locations was along what he called the ‘Arkley-Shenley Road’ (marked on contemporary maps as Rowley Lane). This was an area of wetland, with plenty of ponds and streams which would have been brimming with the kind of pond life that Smith often sought out as subjects for his films. It also happened to be close to the BIF studios: we might imagine him combining visits to production headquarters with the opportunity to collect specimens for future work. Here, he collected a range of microalgae including Vorticella, Carchesium, Actinosphaerium and Volvox. Smith was fascinated by these and other microscopic ‘strange beings’ (Field and Smith, 1944, p 124), and many of his films introduced them to a popular audience for the first time.

Smith was known for using cameras that had long gone out of use, and this is evidenced in the notebooks, which show that he was still using his Urban Bioscope camera from the 1900s until late in his career. Even in 1943 he has using a Kinemacolor camera, which was released by Charles Urban in 1908. This camera was used in an early colour process, and Smith had shot some of his first films using this technique. However, the notebooks suggest that he had adapted the camera to shoot ordinary black and white footage, possibly taking advantage of the fact that the camera was built to take images at twice the usual speed (32 frames per second). Because the colour effect was achieved by projecting the film stock through alternating filters, instead of using special film stock, he was able to use the camera long after the Kinemacolor process had sunken into obscurity. According to the notebooks, Smith also used several other cameras, including a Williamson likely to date from the 1910s, and a Newman-Sinclair, which first launched in the late 1920s and was a favourite of interwar documentary filmmakers. Each of these cameras had a wide range of possibilities with regards to lenses, lighting and attachments, all of which were recorded in the notebooks. Smith used two main microscopes, labelled AH I and AH II, which could each be adapted for use with a number of special stages designed for observing different kinds of specimens. He also owned two ‘Devil’ motors, which he used to operate those cameras which were originally designed to be turned by hand.

Smith’s assistants: Kate Smith and Phyllis Bolté

It seems likely that these detailed notes were not simply for F Percy Smith’s own reference. In fact, they shed light on an aspect of his work that has so far remained largely hidden: the involvement of other people in his filmmaking practice. There are various hints in the notebooks that indicate the presence of these people in the process of filmmaking. For example, the notes distinguish between pieces of equipment owned by Smith and those belonging to British Instructional Films, which might indicate that Smith was anxious that his property might go missing when handled by others. The notebooks also refer to various other sources of written information (presumably lost), such as ‘lab catalogue’ and ‘Funaria folder’. Although the keeping of such detailed records may not in itself confirm that other people were present in the Smith studio-laboratory, it is easy to see that this kind of information would have been highly valuable – necessary, even – if Smith was depending on assistants or collaborators to help him keep track of the various films that were usually being made simultaneously under his watch. Thankfully we do not need to rely on speculation based on the notebooks alone to prove that Smith frequently enlisted additional help, as we know from other sources that this was in fact the case.

Although he was often portrayed in the press as a solitary figure who worked alone, we know that Smith had at least two helpers. The first was his wife Kate (née Ustonson, 1880–1959). Kate is often described as the epitome of the long-suffering but supportive partner, a ‘devoted and protective companion’ according to one biographer (McKernan, 2004). A contemporary journalist, moreover, described her as a ‘truly ideal wife for a scientist’, adding that she was ‘a woman of few words, quick and alert, able to grasp what he wants and needs at the slightest hint, and with no small degree of real scientific knowledge herself’ (Woollcombe, 1936). Mention of Kate’s involvement in making the films was often used to emphasise the total blending of the domestic and the professional that characterised Smith’s work. The documentary filmmaker Grahame Tharp, for instance, mentions Kate Smith only as a housewife arriving to remind her husband that lunch had been prepared (Tharp, 1941, p 11). Kate’s domestic work alone is worthy of mention as part of her husband’s filmmaking, performing a role long associated with the wives, sisters and daughters of male scientists (Jones and Hawkins, 2015; Fara, 2018; Shteir, 1997; Jones, 2016).

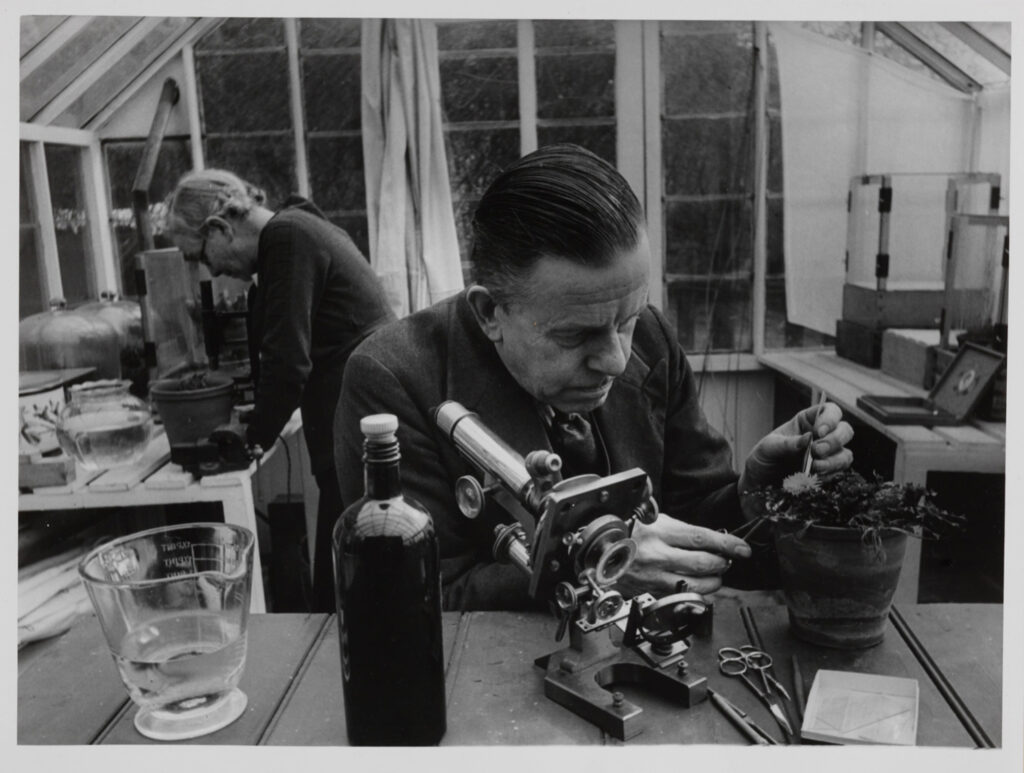

The total blending of the Smiths’ domestic and private life is illustrated in the notebooks, with filmmaking and scientific equipment stored in every corner of their sprawling household, proving the fruitlessness of trying to untangle both spheres from one another. However, they also permit us to attribute a more direct involvement by Kate in the studio-laboratory’s work, recasting her as more than a passive observer and supportive wife, and instead as an active co-producer of Percy Smith’s films. In Figure 4 she is pictured alongside her husband, in one of several images that convey her close involvement with his filmmaking. Both are leaning over a small glass tank used for shooting underwater sequences. While Percy commands the attention, inspecting a snail with grubby hands, Kate is no mere spectator. Just visible behind the tank is a long pair of tweezers that she is holding: it looks as though she has just extracted the snail and handed it to Percy to observe.

In other photographs, Kate is pictured working diligently in the background, as in Figure 5. While Percy is again the principal subject of this picture, the image clearly shows Kate working separately and independently behind him, in a way that we might imagine was typical of the couple’s working habits. To one visitor to the Smith studio-laboratory, Kate’s contribution to the films was self-evident: ‘She acts as his assistant in all stages of the work, except in the actual designing and making of mechanical parts’ (Roberts, 1939). Other newspaper articles also referred to Kate as Percy Smith’s ‘assistant’, with one noting that ‘altogether they have made 200 pictures’ (Anon, 1939). According to the journalist Irene Wilson, the couple spent their honeymoon in 1907 filming flying ants together (Wilson, 1945), which would suggest that Kate’s involvement with her husband’s filmmaking stretched right back the earliest years of their relationship. Indeed, the couple had grown up on the same street in Islington, Cloudesley Place, and in later recollections Smith remarked on their shared passion for collecting insects from a young age (C, I, 1938).

In the 1901 census, before her marriage to Percy, Kate’s occupation is listed as ‘spectacle glazier’, a specialised skill that had been associated with her family’s name for generations.[5] Her father, Thomas Ustonson, described himself as a ‘phil. inst. and spec maker’ in the 1881 census.[6] The latter part indicated that he made spectacles. Previously he had described himself as simply an ‘optician’, which would suggest that this was his principal trade.[7] Thomas’s father and grandfather had also been opticians. ‘Phil. inst.’ stood for ‘philosophical instruments’, which could mean all kinds of scientific tools, including test tubes and microscopes. We know that the skills available to nineteenth-century optical manufacturers, particularly in lens-cutting, could be applied to making a range of scientific devices, and it is possible that Kate’s father undertook some work of this kind (Roberts, 2017; Almond, 2022). Kate’s father died in 1891, when Kate was only ten years old. At that time, her elder siblings Emma, Philip and Bertie had already taken up the family trade, and perhaps it was they who later helped Kate to build up her own skills.[8] Given this background, it is reasonable to expect that Kate would have found every opportunity to put her technical skills to use later in life: after all, from mounting camera lenses to customising and operating microscopes, her expertise would have been highly relevant and useful to the activities of the Southgate studio-laboratory. We might even speculate that a shared interest in ‘tinkering’ had brought the Smith couple together.

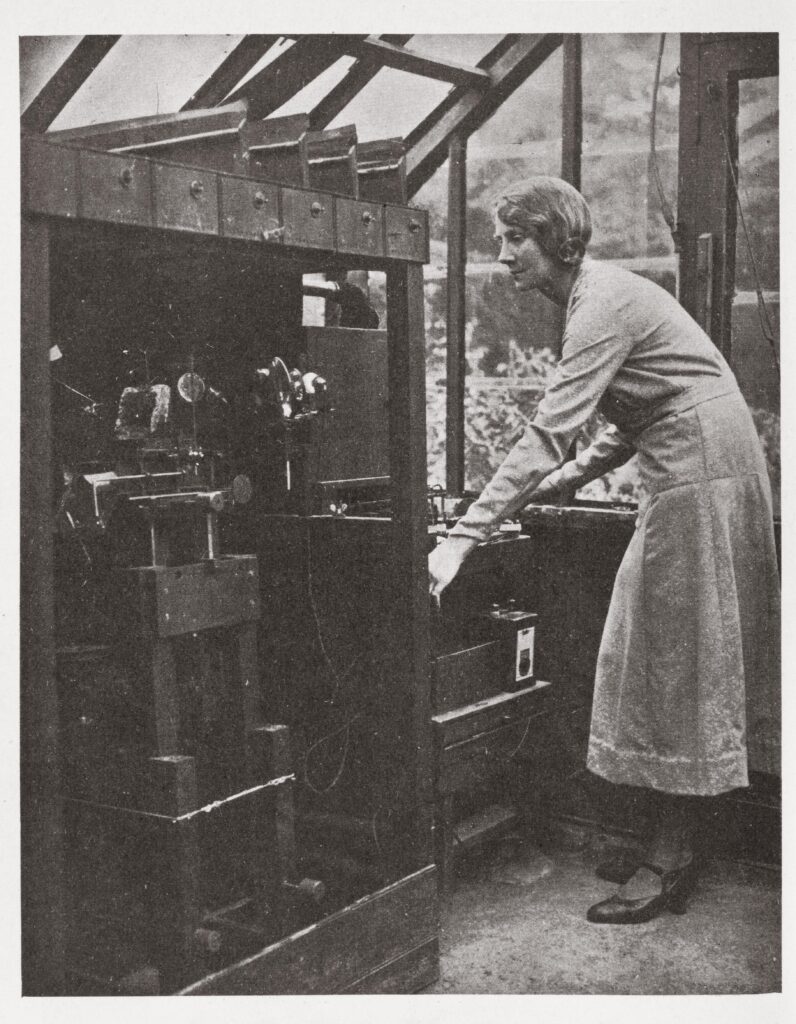

Although it is often maintained, as his obituary in Nature put it, that ‘the only assistant he would tolerate was his wife’, we know that Smith had at least one other helper (Anon, 1945a). This was Phyllis Penn Bolté, an elusive figure who appears only occasionally in contemporary discussions of Smith’s work and has vanished entirely from historical discussions of his films. She is pictured in Figure 6, a photograph printed in Mary Field and Percy Smith’s 1934 book about the Secrets series (Field and Smith, 1934), which shows her standing beside a ‘plant machine’ used for taking time-lapse films of plant growth.

This contraption enabled Smith and his assistants to take pictures, at equal intervals, of a plant’s development. It also ensured that pictures were taken in a controlled environment, without the variations in light that would otherwise spoil the image quality. The camera was operated by a handmade timer, which would also close a system of slats (visible in the picture at the top of the machine), and activated a lamp trained on the plant. Bolté’s pose in the photograph displays a degree of comfort and confidence that reveals her familiarity with the machine and its workings. In the notebooks, we also find traces of her presence in several references to the ‘Bolté shelves’, which could indicate a place in the laboratory where she kept her own equipment. Smith called Bolté ‘my eagle-eyed assistant’ (Smith, 1931), and described her role in the filmmaking process as follows:

An association of this kind is in no way analogous to that of Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson, but comparable rather to the relationship between the right and left hands, which, mutually endeavouring to grasp a desired object, gain in efficiency from the fact that they approach it from different directions (Field and Smith, 1934, p 187).

Mark Burgess, who wrote an otherwise highly informative account of Smith’s life (Burgess, 1993, 1994a, 1994b), suggests that this comment is an exaggeration, attributing it to a ‘reaction to her sudden and early death’ (Burgess, 1994b, p 330). However, Bolté was still alive at the time of the book’s publication: there is every reason to take seriously Smith’s comments about her contribution to Smith’s films. Multiple contemporary sources confirm, moreover, that Bolté’s responsibilities reached far beyond that of a casual helper. The journalist Mary Benedetta’s account of her visit to the Southgate studio-laboratory in 1934 suggests that Bolté was in fact indispensable to Smith’s film work:

Mr Smith has a girl assistant, Miss Phyllis Penn Bolté, whom he has taught to understand the apparatus and who has worked with him for fifteen years. When they are setting the experiments there is so much for them to remember that they have to follow each other about, reminding themselves what to do. One tiny thing forgotten would mean a whole nature film ruined (Benedetta, 1934).

Far from a mere assistant, this description casts Bolté as a colleague and co-producer of Smith’s.

Bolté died in 1935, at the age of thirty-four, of cholemia and toxic hepatitis.[9] Although it is impossible to draw a direct link between her early death and her work for Smith, frequent exposure to the chemicals that circulated in the Southgate laboratory (which included ammonia, mercury nitrate, nitric acid, and lead paint) may have significantly increased her chances of contracting liver damage. The daughter of ‘master confectioner’ and ‘cabinet maker’ Philip Hase Bolté and ‘confectioner’ Minnie Penn Bolté, she began working for Smith around 1919.[10] We do not know how Bolté first met the Smiths, but by the time she started collaborating with them she did so as a ‘personal friend’ (Field and Smith, 1934, p 186). Her death certificate, however, lists her as a ‘scientist’s assistant’, suggesting that her role had become more formalised over the years.[11] Unfortunately, we know very little about her working conditions, or even how much Bolté earned for her labour. When she died, she left behind £286.[12] This was nearly double the average yearly wage for a male manual worker in 1935, and four times that of a female manual worker, but it also was not a fortune (Gazeley, 2007, p 67). The 1921 census lists Bolté, then twenty years old, as living with the Smiths, and she reported her occupation as an ‘apprentice’ who was ‘Learning Photography etc’.[13] By the time she passed away, then, she had been working alongside Percy and Kate Smith for over fifteen years, during which time it is reasonable to assume that she had become intimately acquainted with all the necessary techniques and methods used to make science films in the Smith household.

The fact that similar notebooks do not survive prior to the 1920s might indicate that the ‘Data’ notes were produced partly as a response by Smith to working with a new assistant. According to H Bruce Woolfe, Smith’s equipment had remained dormant for a period between the end of the First World War and when he first approached Smith to work for Secrets of Nature around 1924 (Burgess, 1994a, p 239). Starting work for Secrets of Nature meant redesigning old parts as well as building entirely new machines. As his assistant at the time, we would expect that Bolté was involved in this process of redesigning and repurposing, and perhaps the notebooks served for both Percy Smith and Bolté to keep track of the full range of equipment that they used. Interestingly, Percy Smith described Bolté as being ‘unspoilt by technical training’ (Field and Smith, 1934, p 187) and elsewhere added that ‘the more usual technicians and experts are not the type to take up the work’ (Woollcombe, 1936). This comment is partly indicative of the idiosyncrasies of Smith’s working methods, which required any assistant to be trained from scratch in the laboratory itself. However, it also might suggest that Smith also had some prior experience of working with other assistants, whose ‘technical’ knowledge (which could here refer either to photography or to science) had proven to be an obstacle. As we will see later, the notebooks testify to how later in his career Smith increasingly worked alongside people who did have this kind of technical training, some of whom may also be considered ‘assistants’ of his.

The notebooks alone offer relatively little in the way of evidence for the specific roles played by Kate Smith and Phyllis Bolté in Percy Smith’s filmmaking. However, when viewed alongside a range of other sources including newspaper articles, photographs, census records and Percy Smith’s own writing, it becomes clear that both women were indispensable to the work that lay behind the films that so far have been credited to Percy Smith’s name alone. In this respect, their work may be considered roughly analogous to that undertaken by scientific technicians and assistants, many of them female, in early-twentieth century laboratories (Hartley and Tansey, 2015; Morus, 2016). Nevertheless, the Smith studio-laboratory was very unlike the increasingly professionalised laboratories of twentieth-century science, especially in its blending of the domestic and the scientific which harked back to an earlier era. Reinserting Kate Smith and Phyllis Bolté into the history of popular science therefore contributes to painting a fuller picture of how scientific knowledge continued to be shaped and produced in these non-academic spaces in the first half of the twentieth century.

The craft of scientific film in the ‘Data’ notebooks

The notebooks permit us to place natural history filmmaking within a much more expansive definition of science media, one which treats scientific film not only as a technology of reproduction and communication, but also as a fundamentally material ‘craft’, involving the creative and resourceful use of a wide range of objects, specimens and tools. Focusing on the idea of craft has enabled scholars to underscore how things like materials or labour conditions have shaped the production of scientific knowledge across a wide range of periods (Shapin, 1989; Kuijpers, 2019; Russell, 2014). Moreover, as Michael McCluskey has argued, amateur cinema in 1920s and 1930s Britain was closely tied to the concept of craft (McCluskey, 2019). In the Smith laboratory in Southgate, craft was the foundation on which many of the scenes from the popular series Secrets of Nature were built. The ‘Data’ notebooks thus offer a window into the staging of natural knowledge for a public cinema audience. They are also fascinating documents which lay out the range of skills, materials and processes that were required in this staging. Finally, craft has often been associated with feminine labour: I use the term here in part to recentre the role of Smith’s female assistants in the filmmaking process as described in the previous section of this article (Thomas, 2020; Elkins, 2022).

The list of materials that appear in the notebooks is vast. For ‘silvering’ mirrors, they list tartrate sugar, ammonia, and silver nitrate. For different types of modelling, they refer to wax and plasticine, while cement and plaster are listed in the ingredients needed for imitating rocks in different conditions such as underwater or in the soil. Other materials included in the notes include petrol, paraffin, resin, varnish, several types of dye, plastic, rubber, wire, shellac, gelatine, sand, clay, asbestos, wool, feathers, manure and turpentine. The notebooks also contain references to thin card, tracing paper and cartridge, sub-cartridge and ‘thicker cartridge’ paper. Most of the studio-laboratory’s paper supplies came from Reeves and Sons, Ltd, an artists’ supplies business with shops in multiple locations across central London. The notes include instructions on soldering metals, as well as how to manufacture special kinds of putty and cement for sticking together different materials such as metal and glass. Here we encounter one of the multiple failed experiments recorded in the notebooks: ‘Did not harden properly – whole show collapsed.’

From Woolworth’s, the Smiths purchased an enamel paint called ‘Enamelit’, as well as ‘oblong butter dishes with lids’ and triangular glass dishes to make culture trays for growing mosses and fungi. These were the products of modern consumer society, and Percy Smith and his assistants relied on them to produce the spellbinding images that would become associated with his name. In this way, the Southgate studio-laboratory was a place where the craft process was central to shaping new ways of looking at the natural world. This was made possible through the combination of modern chemicals, tools and everyday domestic items together with the living plants, animals and other organisms that were the films’ principal subjects.

The notebooks record how a range of materials, including horse manure, roots, feathers and conifers, were useful for simulating natural environments. They list ‘moist cells’ made with either ‘gels’ or plaster, as well as culture trays for ferns, mosses and ‘myxies’ (the slime mould myxomycete shown in the 1931 film Magic Myxies). ‘Extra tall’ troughs were ‘for growing water weeds’, while a ‘dry trough’ was used principally for filming the blowfly’s behaviour underground. Tanks were designed specifically with different animals in mind: the notebooks include instructions for building a ‘Gnat Tank’, ‘Skater Tank’, ‘Trout Tank’ and ‘Newt Tank’ (presumably used for the 1932 film Romance in a Pond). These tanks were designed with a view to controlling environmental conditions and maximising image quality and consistency. The notes are replete with detailed instructions on the different shots and angles that were possible with each contraption. For instance, the directions for a ‘Top Light Tank’ record the position of the tripod, the distance of the camera from the tank, and the lens used for frontal, slanting, middle-depth and ‘underneath’ shots. The notes also include details about a ‘Skeleton Tank’, which was a ‘general utility device for critical focus purposes’. This seems to have been a kind of ‘outer’ layer that could be added to a tank or trough, in which the photographer could place pebbles, sand and weeds to extend the depth of field and achieve greater ‘pictorial distance’. Ensuring that the tanks had the right kind of background was key too. ‘Pisciculturists Black Varnish’ from Haig in Surrey, for instance, was ‘very successful’ for painting the glass of aquaria.

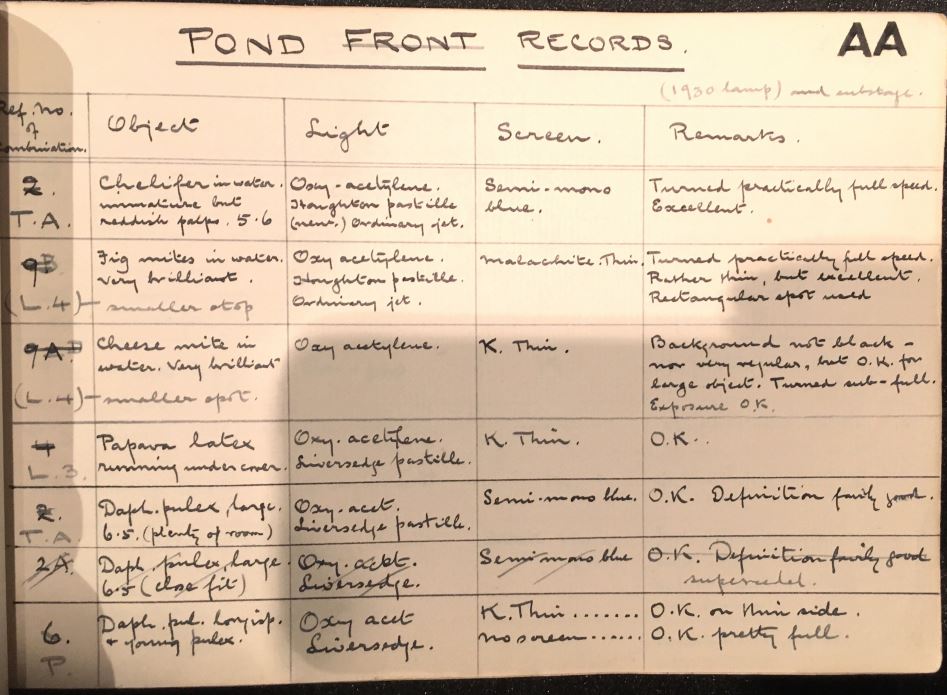

The notebooks also record the results of various experiments with different combinations of equipment, presumably from tests made by Smith and his assistants. Figure 7 is a typical example of a table displaying the results of one such experiment, in this case testing different lighting effects using the Kinemacolor camera. The first column assigns an individual code to the combination of equipment used, while the second records the subject filmed on that occasion: the insect Chelifer (a type of ‘pseudoscorpion’), fig mites, Papava (probably meaning Papaver, or poppy) and the water flea Daphnia pulex. The second and third columns describe, respectively, the lighting apparatus and screens, while the last column records overall remarks (‘excellent’, ‘not very clear, but OK’) on the resulting image. The penultimate row is crossed out in pencil, with a note reading ‘suspended’: the notebooks bear witness to numerous failed experiments like this one. In some cases, film samples from different experiments were kept for future consultation, in a box labelled ‘film cuts’. Presumably these could be used as a point of reference to ensure consistency.

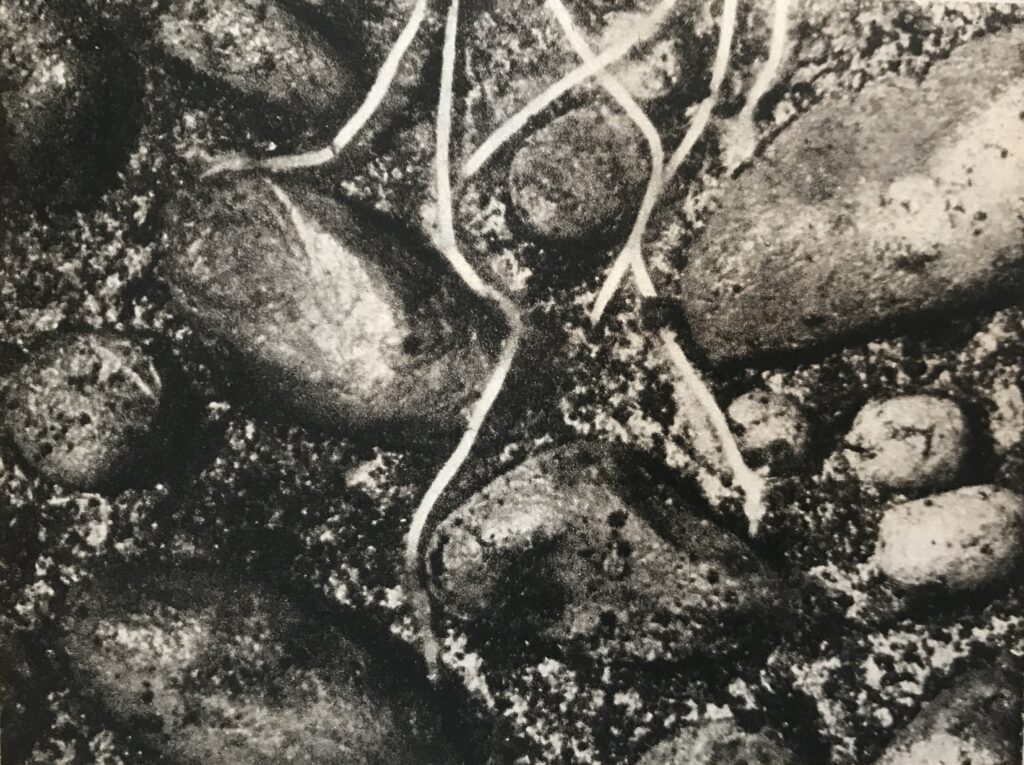

Imitation ‘rocks’ could be crafted by using four different methods: cellophane, plasticine, plaster, and cement. Some of these were ‘root rocks’, which were used for shooting underground cross-sections of root growth, as in the film Amazing Maize (1933), where the roots of the maize plant are shown navigating past obstacles in the form of stones (Figure 8). In Down Under (1930), moreover, an entire Secrets film showed the different behaviours of roots growing underground. To capture this footage, Smith had to find ways to film a cross-section of root growth in pitch darkness, so as not to harm the roots. In a 1930 speech, he explained that these shots were achieved by using ‘two bricks of clay lined with a suitable material for stimulating growth. A row of peas is sown on the surface of the bricks at a point where they meet, and their roots, seeking the line of least resistance, travel down between the two bricks’ (Anon 1930a). Ordinary rocks and stones would not have fit into this narrow space, hence the need to make models. The notebooks show that he employed ‘face openings’ and ‘flap devices’, which allowed the roots to grow undisturbed and could be opened periodically for the image to be captured.

The notebooks also show how relatively simple things like soil were engineered in order to capture certain effects on film. ‘Pot masks’, for instance, were used to hide plant pots from view, creating the illusion of a continuous soil floor with a black background, which became Smith’s signature style. They were especially useful for showing a seedling’s ‘visible push through surface’, as can be seen in Figure 9, where the soil in the foreground was made with one of these ‘pot masks’. Varying combinations of ingredients were used to imitate different types of soil, including a ‘wet soil effect’. The mixture for these masks included pale resin, beeswax and varying amounts of sand and peat.

The notebooks list the range of visual ‘effects’ that Smith had at his disposal, including simulations of the view through a pocket lens or a microscope field, or a mechanism to make plants seem like they were ‘wind-blown’. Moreover, to simulate lightning in the film The Changing Year (1932), Smith made a solution using sodium sulphite and mercury iodide, which he applied straight onto the film stock using a camel-hair brush, before rinsing and finally developing the film. This process, known as ‘intensification’, was ordinarily used to improve the contrast in under-exposed negatives (Wahl, 2020). Lighting could also achieve a range of effects. The laboratory contained a wide range of bulbs, labelled with names like ‘small and tubular’ and ‘small ruby’. Methylated blue and other chemicals were used to dye glass plates a range of different colours. These would block certain light frequencies, reducing the heat of the illumination, which otherwise risked spoiling specimens.

The notebooks also reveal details about Smith’s modelling and animation work. Smith had started making animation films early in his career, and during the First World War he produced a series of animated Kineto War Maps (Hale, 2018). From the notes, we learn that ‘Bertie the Bee’, a model bee that Smith devised to illustrate pollination, was made using ‘dyed fur’ (Figure 10). Smith explained that models were necessary particularly in cases where filmed sequences would be ‘incomprehensible to an untrained observer’, adding also that often audiences were ‘unable to decide as to what is actual and what is model’ (Field and Smith, 1934, pp 176–7). Wax was used to create ‘petals etc.’, while an Amoeba was modelled out of plastic. A sheet with the heading ‘Modelling Colours’ indicates the pigments he used for individual parts of a plant, including ‘Pink petal base’, ‘pollen orange’ and ‘leaf green’. As well as models, Smith often contributed animal diagrams for science films, for instance to illustrate physiological details that would be difficult to capture on film. These diagrams were sometimes blended with live action images, and the notes record different methods to produce effects, such as by fading several frames into a single image. One method was ‘designed 1937 for nuclear division of paramecium’, while another was for ‘showing internal structures, external parts remaining, in a reduced density’. An example of this effect is shown in Figure 11, where the outer coat of an onion seed fades away, revealing the radicle inside. These instances show clearly how Smith devised new solutions to meet changing production demands. In this case, he was responding to a significant shift towards instructional content from the mid-1930s, when the Secrets of Nature team moved to a new production company, Gaumont-British Instructional (G.B.I.), where they continued to produce a new series of natural history film, Secrets of Life (Long, 2020). However, G.B.I. also began to focus their efforts on increasingly technical educational films, and Smith was commissioned to do much of the cinematography on their biological classroom films. Working on this new class of film required Smith to have closer contact with a variety of individuals with technical or scientific training.

Scientists and new apprentices

The educational films made by G.B.I. in the 1930s focused mostly on biological topics for secondary school pupils and first-year university students, although simpler versions were also made for younger learners. For Smith, this involved working alongside established scientists including Julian Huxley, Edward Salisbury and H R Hewer. He also collaborated with J V Durden, who rapidly became a key director of scientific films. Durden had completed a BSc in Zoology and Entomology at Imperial College, under the direction of Hewer. When Durden began working for G.B.I. in 1935, he had no prior experience in the film industry; by 1947, shortly after Smith’s death, he had established his own company specialising in the supply of scientific film footage, Photomicrography Ltd (‘specialists in Ciné-Biology’) (Anon, 1948). It seems plausible, then, that he learned some of his skills under Smith’s tutelage. Where else could he learn complex techniques such as time-lapse photography, if not from Smith, alongside whom he is credited in multiple films? Durden’s appearance on the scene also helps to explain another question: how did Smith make up for the loss of Phyllis Bolté following her death in 1935? After losing his assistant of more than fifteen years, it would have been difficult for Smith to maintain his usual output, especially at a time when footage was needed for both educational and entertainment films. Accounts of the Southgate studio-laboratory from the late 1930s testify to Kate Smith’s continued involvement in Percy’s filmmaking (Roberts, 1939; Anon, 1939), but it’s possible that he also received help from younger filmmakers, among them Durden, who were eager to master the skills of scientific filmmaking. Durden, in turn, may have used his scientific training to help Smith to work on new devices or to improve existing machinery. In this context, the notebooks may have been a highly valuable learning tool for Durden and others, playing a small part in the intergenerational transfer of knowledge about scientific filmmaking in the mid-twentieth century.

The impact of these new collaborations on Smith’s modus operandi is clearly discernible in the notebooks. For instance, a miniature aquarium that Smith named the ‘Hydra Trough’ was an addition from this period, likely designed for shooting the film Hydra (1936). It became a standard piece of equipment in Smith’s laboratory, with further additions being made in 1943. In Figure 12, Smith is pictured alongside it. He also designed a ‘chick outfit’ during these years, which he made for filming The Development of the Chick (1937). This film, one from a series of six films about embryology, was one of the earliest classroom films to show the development of the chick embryo while still inside the egg, and reportedly took three years to shoot. In this work, Smith may have drawn from the earlier experiments of Ronald Canti, a pathologist at the Strangeways Laboratory in Cambridge. In the late 1920s, Canti had begun using film in his research, producing a much-praised film about living tissue, and filming living chick embryos using an incubator and other apparatus that he built in his home (Landecker, 2011; Waddington, 1932). Durden, who is listed as the director of The Development of the Chick, would go on to make a colour film on the same subject for the Film Board of Canada in 1953, likely applying some of the techniques that he had learned previously alongside Smith.

Some of the equipment that Smith devised to make The Development of the Chick is listed in his notes, including an ‘egg drill’, ‘embryo lifters’ and ‘incubators’. Part of this apparatus is preserved in the collections (Figure 13). It consists of a rectangular wooden box divided into three compartments. The two outer compartments each have a round hole cut into the side of the box, while the central one contains a raised stage holding a circular container. Underneath the stage, a metal rod connects with a sprocket on the outside of the box, which in turn are connected to electric wires. Although the precise intended use of this box is unclear, interpreted with the help of the notebooks it seems likely to have doubled as an incubator and a microscope stage. The round holes were likely for warm air to circulate under the raised stage, creating the right temperature conditions for the egg to hatch in the embedded container, on which the microscope and camera could be fitted. This matches Smith’s notes under the heading ‘Incubator Room’, which detail a ‘Special thermostatic stage’ which guaranteed ‘maximum efficiency for egg area’, a ‘Look-down’ mechanism that allowed ‘three views’ to be captured without moving the camera, and a system of ‘interstage gears’ operated by a motor and a sprocket.

The chick embryo equipment was just one of several items listed in the notebooks under the heading ‘Zoological Apparatus’, which also included a ‘Toad Cave’ and a ‘Frog Table’. These items were designed in the late 1930s and early 1940s and reflect the influence of expert consultants at G.B.I. on Smith’s work. Smith continued to develop new equipment into the 1940s, when, as well as providing footage for the Secrets of Life series, he worked on a Junior Biology series of instructional films commissioned by the British Council and directed by Mary Field, including The Life History of the Onion (1943) and The Life Cycle of the Newt (1943). For these films, which were also formally overseen by a team of consultants, Smith again invented new pieces of equipment or improved existing ones. Instructions for a ‘moist chamber’, for instance, were accompanied by the note ‘Devised 1942 for Onion seed but has wide range of usefulness’: this clearly referred to his work on the 1943 film for the British Council.

Durden was not the only one likely to have learned his skills directly from F Percy Smith. Following his death in 1945, Kate Smith passed on most of her husband’s equipment to Science Films Ltd, a company that H Bruce Woolfe established back in the mid-1930s, mostly to make scientific footage for G.B.I. (Anon, 1945b). Kate retained shares in the company until her death in 1959, which suggests that her husband may have been a part owner when he was alive.[14] Frank Goodliffe was Director of Productions at Science Films until 1945, when he was succeeded by Norman Macqueen, who would later start Science Review, one of the BBC’s first ever science television programmes (Anon, 1945b; Hall, 2021, p 77). Both may have learned many of their techniques, including microcinematography and time-lapse, directly from Percy Smith. Another filmmaker, Grahame Tharp of the Shell Film Unit, was collaborating with Smith on a film about malaria shortly before the latter’s death, and wrote a detailed account of the Southgate studio-laboratory which suggests he was very familiar with Smith’s working methods (Tharp, 1941). When handing over her husband’s filmmaking equipment, no doubt Kate Smith’s extensive knowledge of their workings, as well as the notes contained in the ‘Data notebooks’ would have been useful to their new owners. The notebooks therefore invite us to imagine the kinds of knowledge exchange and transfer that took place across subsequent generations of British scientific filmmakers in the mid-twentieth century.

Conclusion

This article has contextualised F Percy Smith’s ‘Data’ notebooks by drawing links between their contents and a range of other historical materials, including photographs, published books and Smith’s own films. Treating the notebooks as evidence of Smith’s ‘craft’ practice, it has documented the rich materiality of Smith’s laboratory, which testifies to the importance of incorporating an expansive definition of ‘media’ into our histories of scientific filmmaking. The notebooks show Smith’s ‘tinkering’ in action, from his trips to collect specimens across a range of sites in North London, to his designs for a range of different ‘troughs’ and ‘tanks’. They testify to the way that Smith’s output in this period was subject to a large degree of continuous experimentation, and they reveal the degree to which films like the Secrets of Nature series relied on the creation of tightly controlled environments and highly elaborate sleights of hand. The notebooks also carry hints of the other individuals involved in Smith’s filmmaking process, including his wife Kate, and his ‘assistant’, Phyllis Bolté. By reading the notebooks in conjunction with a range of other sources, we can conclude that both women’s involvement in the filmmaking process was more than incidental: the notion of F Percy Smith as sole author of the work produced in this period is therefore no longer tenable. Beyond Kate Smith and Phyllis Bolté, the notebooks might also have been of use to a later generation of science filmmakers, among them J V Durden and Grahame Tharp. By drawing into focus the wide range of materials, methods and individuals involved in the filmmaking process, this article has demonstrated the value of incorporating a wider range of sources into existing analyses of twentieth-century scientific filmmaking.